Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) agonists are used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. However, the currently used PPARγ agonists display serious side effects, which has led to a great interest in the discovery of novel ligands with favorable properties. The aim of our study was to identify new PPARγ agonists by a PPARγ pharmacophore–based virtual screening of 3D natural product libraries. This in silico approach led to the identification of several neolignans predicted to bind the receptor ligand binding domain (LBD). To confirm this prediction, the neolignans dieugenol, tetrahydrodieugenol, and magnolol were isolated from the respective natural source or synthesized and subsequently tested for PPARγ receptor binding. The neolignans bound to the PPARγ LBD with EC50 values in the nanomolar range, exhibiting a binding pattern highly similar to the clinically used agonist pioglitazone. In intact cells, dieugenol and tetrahydrodieugenol selectively activated human PPARγ-mediated, but not human PPARα- or -β/δ-mediated luciferase reporter expression, with a pattern suggesting partial PPARγ agonism. The coactivator recruitment study also demonstrated partial agonism of the tested neolignans. Dieugenol, tetrahydrodieugenol, and magnolol but not the structurally related eugenol induced 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation, confirming effectiveness in a cell model with endogenous PPARγ expression. In conclusion, we identified neolignans as novel ligands for PPARγ, which exhibited interesting activation profiles, recommending them as potential pharmaceutical leads or dietary supplements.

Western lifestyle with a high intake of simple sugars, saturated fat, and physical inactivity promotes pathologic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, which are currently taking a devastating epidemical spread worldwide. Compounds that are activating PPARγ may help to fight these pathological conditions (Cho and Momose, 2008).

PPARs are ligand-activated transcription factors belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily, and their main function relates to the regulation of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism (Tenenbaum et al., 2003; Desvergne et al., 2006). Three isoforms of this nuclear receptor have been identified so far: PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ. PPARα is highly expressed in skeletal muscle, liver, kidney, heart, and the vascular wall, and it was shown to be mainly involved in the regulation of lipid catabolism (Fruchart, 2009). PPARγ is predominantly expressed in adipose tissue, and its activation promotes adipogenesis and increases insulin sensitivity (Anghel and Wahli, 2007). More recently, PPARγ has been shown to be involved in the regulation of genes contributing to inflammation, hypertension, and atherosclerosis (Gurnell, 2007). PPARβ/δ has a broader expression pattern and is involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism and energy expenditure (Bedu et al., 2005; Luquet et al., 2005).

Once activated by their ligands, the PPARs translocate into the nucleus, form heterodimers with the retinoid X receptor (RXR), and subsequently bind to PPAR response elements (PPREs) that are located in the promoter regions of PPAR-responsive target genes (Bardot et al., 1993). Binding of the PPAR-RXR heterodimers to the PPREs triggers further recruitment of diverse nuclear receptor coactivators (SRC-1, TRAP220, cAMP response element-binding binding protein, p300, PGS-1, and/or others), contributing to the transcriptional regulation of the target genes (Yu and Reddy, 2007).

PPARγ activators are currently used as insulin sensitizers to combat type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome (Cho and Momose, 2008). However, the PPARγ agonists in clinical use, represented by thiazolidinediones (TZDs), have serious side effects such as weight gain, increased bone fracture, fluid retention, and heart failure (Rizos et al., 2009). Therefore, the discovery and optimization of new PPARγ agonists that would display reduced side effects is of great interest. TZDs are full PPARγ agonists inducing maximal receptor activation. It is noteworthy that partial PPARγ agonists recently came into focus as a possible new generation of promising PPARγ ligands. Partial agonists induce alternative receptor conformations and thus recruit different coactivators resulting in distinct transcriptional effects compared with TZDs. There are firm indications that such partial agonists might retain the needed effectiveness and have reduced side effects (Yumuk, 2006; Chang et al., 2007).

Natural products are an important and promising source for drug discovery (Newman and Cragg, 2007). The aim of our study was, therefore, to identify natural products that activate human PPARγ (hPPARγ) acting possibly as partial agonists. To achieve this objective, we used an in silico approach making use of a pharmacophore model for hPPARγ developed previously (Markt et al., 2007, 2008) and 3D databases of natural products. The conducted virtual screen using two 3D databases and the pharmacophore model led to the identification of neolignans. The three neolignans, dieugenol, tetrahydrodieugenol, and magnolol, were isolated from the respective natural source or synthesized and characterized in several PPARγ-specific in vitro models or intact cells.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals, Cell Culture Reagents, and Plasmids

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g/liter glucose was purchased from Lonza Group AG (Basel, Switzerland). The fetal bovine serum was from Invitrogen (Lofer, Austria). GW7647, GW0742, and BADGE were purchased from Cayman Europe (Tallinn, Estonia). Pioglitazone was purchased from Molekula Ltd (Shaftesbury, UK). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Vienna, Austria). The test compounds were dissolved in DMSO, divided into aliquots and kept frozen until use. In all test models, a solvent vehicle control was always included to assure that DMSO does not interfere with the respective model. For all cell-based assays, the final concentration of DMSO was kept 0.1% or lower. The PPAR luciferase reporter construct (tk-PPREx3-luc) and the expression plasmid for murine PPARγ (pCMX-mPPARγ) were a kind gift from Prof. Ronald M. Evans (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, La Jolla, CA), the plasmid encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (pEGFP-N1) was obtained from Clontech (Mountain View, CA), and the expression plasmids for the three human PPAR subtypes (pSG5-PL-hPPAR-α, pSG5-hPPAR-β, pSG5-PL-hPPAR-γ1) were a kind gift of Prof. Walter Wahli and Prof. Beatrice Desvergne (Center for Integrative Genomics, University of Lausanne, Switzerland).

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

The pharmacophore model used for virtual screening was taken from the model collection reported previously (Markt et al., 2007, 2008). Data mining of the natural product databases was performed using Catalyst 4.11 (Accelrys, Inc., San Diego, CA). For virtual screening, the fast flexible search algorithm of Catalyst was used.

Virtual Natural Product Databases

The two virtual 3D compound databases used in this study have been generated previously. The DIOS database contains 9676 individual small-molecular-weight natural products found in ancient herbal medicines described in De materia medica by Pedanius Dioscorides during the first century CE (Rollinger et al., 2008). The Chinese Herbal Medicine (CHM) database contains 10,216 compounds that are reported to be contained in medicinal preparations used in traditional Chinese medicine. Both 3D databases were generated within Catalyst. 3D structures of the compounds were built and consequently energetically minimized using the structure editor of Catalyst. The catConf algorithm was applied to create conformational models for the compounds using the following settings: maximum number of conformers, 100; generation type, fast quality; and energy range, 20 kcal/mol above the calculated lowest energy conformation.

Isolation

Magnolol (3) was isolated from the bark of Magnolia officinalis Rehd. and Wils. The plant material provided by Plantasia (Oberndorf, Austria) corresponded to the quality described at the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. Powdered bark (880 g) of M. officinalis were exhaustively macerated with dichloromethane (8.0 liters, 12 times, at room temperature) yielding 96.7 g of crude extract. Of the obtained extract, 80.0 g were separated by flash silica gel column chromatography (400 g of silica gel 60, 40–63 μm; 41 × 3.5 cm; Merck, VWR, Darmstadt, Germany) using a petroleum ether-acetone gradient with an increasing amount of acetone resulting in 18 fractions (A1–A18). Fraction A5 (17.29 g) was further separated by means of vacuum liquid chromatography (10 × 5 cm) with LiChroprep RP-18 material (100.0 g, 40–63 μm; Merck) using an acetonitrile-water gradient with an increasing amount of acetonitrile. Fractions eluted with 45 to 60% acetonitrile were combined (4.19 g) and further separated by Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK) column chromatography using a dichloromethane-acetone mixture [85 + 15 (v/v)] as mobile phase (subfractions B1–B17). Fraction B13 (3.67 g) was recrystallized from dichloromethane resulting in 2.32 g of 3 as colorless crystals. The compound was identified by mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy (H-NMR purity >98%). NMR and mass spectrometry data are provided as Supplemental Data.

Synthesis of Compounds

Synthesis of dieugenol (1) was performed by oxidative dimerization of eugenol (4) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) as described by Ogata et al. (2000) and Marque et al., (1998). After recrystallization from 2-propanol, isolated 1 was analyzed by NMR (H-NMR purity >99%). Tetrahydrodieugenol (2) was synthesized by hydrogenation of 1 in a Parr apparatus at 40 psi as described by Ogata et al. (2000). After recrystallization from 2-propanol, compound 2 was analyzed by NMR (H-NMR purity >97%). NMR and mass spectrometry data of 1 and 2 validating the identification of the two compounds are provided as online supplementary information.

PPARγ Competitive Ligand Binding

The LanthaScreen time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) PPARγ competitive binding assay (Invitrogen) was performed using the manufacturer’s protocol. The test compounds dissolved in DMSO or solvent vehicle were incubated together with the hPPARγ LBD tagged with GST, terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody and fluorescently labeled PPARγ ligand (Fluormone Pan-PPAR Green; Invitrogen). In this assay, the fluorescently labeled ligand is binding to the hPPARγ LBD, which brings it in close spatial proximity to the terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody. Excitation of the terbium at 340 nm results in energy transfer (FRET) and partial excitation of the fluorescently labeled ligand, followed by emission at 520 nm. Test-compounds binding to the hPPARγ LBD are competing with the fluorescently labeled ligand and displacing it, resulting in a decrease of the FRET signal. The signals at 520 nm were normalized to the signals obtained from the terbium emission at 495 nm; therefore, the decrease in the 520 nm/495 nm ratios was used as a measure for the ability of the tested compounds to bind to the hPPARγ LBD. All measurements were performed with a GeniosPro plate reader (Tecan, Grödig, Austria).

PPAR Luciferase Reporter Gene Transactivation

HEK-293 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in DMEM with phenol red supplemented with 584 mg/ml glutamine, 100 U/ml benzylpenicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were maintained in 75-cm2 flasks with 10 ml of medium at 37°C and 5% CO2. For transient transfection, cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes at a density of 6 × 106 cells/dish for 18 h, and then transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method with 4 μg of the respective PPAR receptor expression plasmid, 4 μg of reporter plasmid (tk-PPREx3-luc), and 2 μg of green fluorescent protein plasmid (pEGFP-N1) as internal control. The total DNA was kept at 10 μg, and the ratio tk-PPREx3-luc/PPAR/EGFP was kept at 2:2:1. Six hours after the transfection, cells were harvested and reseeded in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) in DMEM without phenol red, supplemented with 584 mg/ml glutamine, 100 U/ml benzylpenicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum. Then cells were treated with the respective compounds and incubated for 18 h. After cell lysis, the luminescence of the firefly luciferase and the fluorescence of EGFP were quantified on a GeniosPro plate reader (Tecan). The luminescence signals were normalized to the EGFP-derived fluorescence, to account for differences in cell number and/or transfection efficiency.

PPARγ Coactivator Recruitment

The LanthaScreen TR-FRET PPARγ coactivator assay (Invitrogen) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The test compounds dissolved in DMSO or solvent vehicle were incubated together with fluoresceinlabeled TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator peptide (Rachez et al., 2000), hPPARγ LBD tagged with GST, and terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody. In this assay, the binding of an agonist to hPPARγ LBD results in a conformational change leading to recruitment of the coactivator TRAP220/DRIP-2 peptide. This recruitment brings the fluorescein attached to the coactivator peptide and the terbium attached to the GST antibody in close spatial proximity, and excitation of the terbium at 340 nm results in a FRET and a consequent partial excitation of the fluorescein that is monitored at 520 nm. The signals at 520 nm were normalized to the signals obtained from the terbium emission at 495 nm, and the 520 nm/495 nm ratios were used as a measure for the TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment potential of the tested compounds. All quantifications were performed with a GeniosPro plate reader (Tecan).

Adipocyte Differentiation

3T3-L1 preadipocytes (American Type Culture Collection) were propagated in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum. For differentiation, the preadipocytes were grown to confluence (day −2) and kept for 2 more days before medium was changed to DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1 μg/ml insulin, and potential PPARγ activators (day 0). In case we wanted to cross-check PPAR dependence of our observations, the PPARγ antagonist BADGE was added 1 h before the addition of the potential agonists. Medium was renewed every 2 days until day 7 or 8. For an estimate of accumulated lipids, and thus for the adipogenic potential of the test compounds, Oil Red O staining was performed. For this, cells were fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 1 h and stained with Oil Red O for 10 min. After washing off the excessive dye, photos were taken, and bound dye was solubilized with 100% isopropanol and photometrically quantified at 550 nm.

Molecular Docking

The molecular docking was performed using the GOLD Suite software (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK). Extraction and preparation of the human PPARγ ligand binding pocket for the docking of two molecules of dieugenol (1), tetrahydrodieugenol (2), and magnolol (3) simultaneously was done within this software. To find a suitable ligand binding pocket, we examined the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Berman et al., 2000) for crystal structures of a PPARγ-ligand complexes. The PDB entry 2vsr provides the X-ray data with the best resolution among all PPARγ-ligand complexes, including two copies of the ligand binding simultaneously to their ligand binding pocket. Thus, we used the ligand binding pocket of this PDB complex for molecular docking. For ligand preparation, we applied Corina 3.00 (Molecular Networks, Erlangen, Germany) and the ilib framework (Wolber and Langer, 2001) to generate 3D structures, and to calculate the protonation states of the neolignans at physiological pH, respectively. The best docking poses were selected based on their GOLDScores and their plausibility. Thus, if a docking pose represented PPARγ-ligand interactions well known from literature, the pose was determined to be more realistic than a higher scored docking pose including unknown and implausible protein-ligand interactions. Finally, the docking pose and the interactions with the binding site were visualized using the LigandScout software 2.0. (Wolber and Langer, 2005; Wolber et al., 2006).

Statistical Methods and Data Analysis

Statistical analysis and nonlinear regression (with settings for sigmoidal dose response and variable slope) were done using Prism software (ver. 4.03; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). One-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test was used to calculate the statistical significance. For comparison of just two experimental conditions, two-tailed paired t test was applied. Results with p < 0.05 were considered significant. Ki values of competitor compounds were also calculated with the use of the Prism software and the Cheng-Prusoff equation: (Ki) = IC50/(1 + L/KD)) (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973).

Results

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

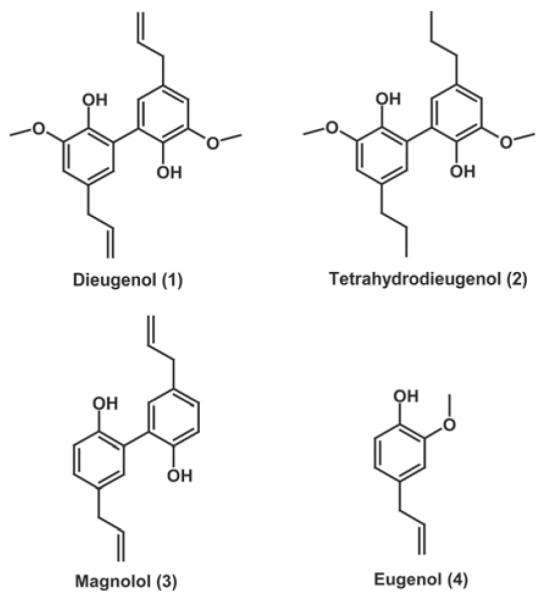

To identify new natural product-derived PPARγ ligands, we used a pharmacophore-based virtual screening approach. The generation and experimental validation of the pharmacophore models were described previously (Markt et al., 2007, 2008). For our study, the best pharmacophore model for PPARγ partial agonists based on the PDB entry 2g0g (Lu et al., 2006) was selected. The generated model consists of three hydrophobic features, one aromatic ring, one hydrogen bond acceptor, and exclusion volume spheres lining the ligand binding domain of PPARγ. Virtual screening of the 3D multiconformational natural product databases DIOS and CHM resulted in 34 (0.4%) and 27 (0.3%) hits, respectively. Highly scored virtual hits were obtained from the chemical class of neolignans. The small-molecular-weight compounds dieugenol (1) and tetrahydrodieugenol (2), both representing dimers of the abundant natural phenylpropanoid eugenol (4), were selected from the hit list. A further neolignan with highly similar structure, magnolol (3), which is a prominent constituent of the traditional Chinese herbal remedy magnolia bark (hòu pò), was also selected for pharmacological evaluation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of the compounds selected for pharmacological investigation.

Isolation and Synthesis Of Compounds

The synthesis of 1 was performed by oxidative dimerization of 4 as described previously. After recrystallization from 2-propanol, the isolated 1 was analyzed by NMR. The melting point was found at 101 to 104°C (Crossfire BRN 2061706 m.p. between 93 and 108°C), and the NMR data are in accordance with the published data (Marque et al., 1998; Ogata et al., 2000). Synthesis of 2 was performed by hydrogenation of 1 as described by Ogata et al. (2000). After recrystallization from 2-propanol, the melting point (147–149°C) and the NMR data were in accordance with the published data (Ogata et al., 2000).

The isolation of 3 from the bark of M. officinalis Rehd. and Wils with the use of different chromatographic methods yielded 0.26%. The compound was identified by mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy and had physical and spectroscopic properties consistent with those reported in the literature (Yahara et al., 1991).

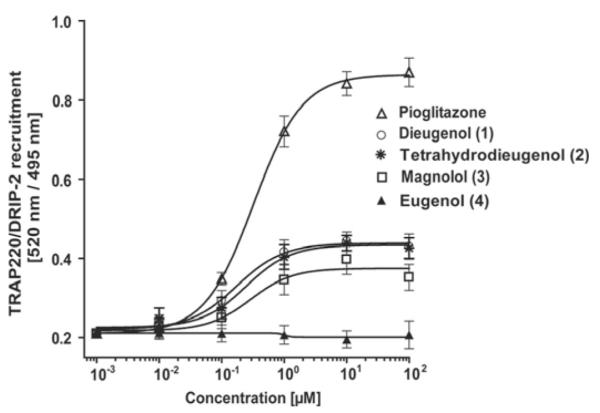

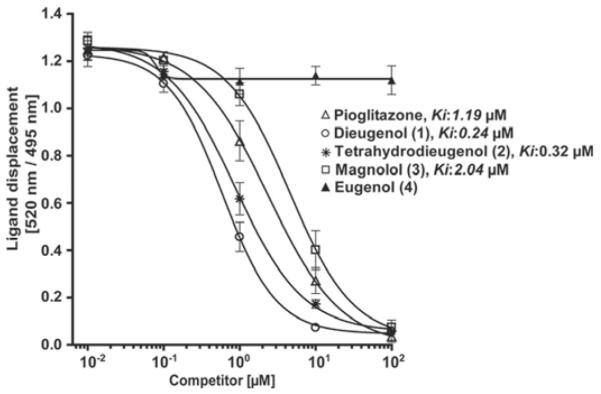

PPARγ Ligand Binding

To validate the predicted hits from the virtual screening approach, we first studied the ability of the neolignans to bind to the purified hPPARγ LBD, assessed by a LanthaScreen TR-FRET PPARγ competitive binding assay. Dose-response studies were performed with 1 to 4 (Fig. 2). Stronger binding of the tested compound to the PPARγ LBD in this assay results in a stronger displacement of the fluorescently labeled ligand (Fluormone Pan-PPAR Green; Invitrogen) leading to a decrease of the FRET signal. Pioglitazone (Actos), a selective PPARγ agonist in clinical use, was used as positive control. Compounds 1 to 3 showed binding properties similar to pioglitazone, whereas 4 did not bind to the receptor at all (at test concentrations up to 100 μM). It is noteworthy that compounds 1 and 2 were binding to the hPPARγ LBD with even higher affinity (Ki values of 0.24 and 0.32 μM, respectively) than pioglitazone (Ki = 1.19 μM), whereas 3 was binding with a slightly lower affinity (Ki = 2.04 μM).

Fig. 2.

PPARγ ligand binding potential of neolignans. Serial dilutions of the tested compounds were prepared in DMSO and then mixed with a buffer solution containing the hPPARγ LBD tagged with GST, terbiumlabeled anti-GST antibody, and fluorescently labeled PPARγ agonist. After 1 h of incubation, the ability of the test compounds to bind to the PPARγ LBD and thus displace the fluorescently labeled ligand was estimated from the decrease of the emission ratio 520 nm/495 nm upon excitation at 340 nm. Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

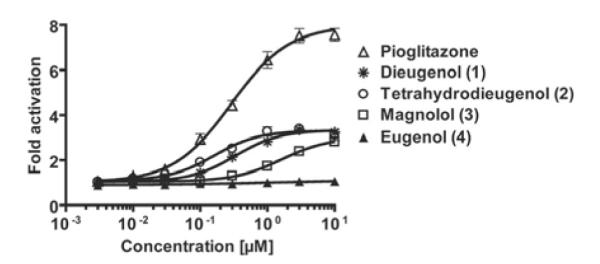

PPARγ Luciferase Reporter Gene Transactivation

To assess whether the neolignans are able to act as functional PPARγ agonists in intact cells, we next performed PPARγ luciferase reporter gene assays. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with a hPPARγ expression plasmid, a PPAR luciferase reporter plasmid (tk-PPREx3-luc), and EGFP as an internal control. Compounds 1 to 3 induced a dose-dependent activation of PPARγ in a concentration range similar to pioglitazone (Fig. 3). The maximal activation in response to compounds 1 and 2 and pioglitazone was achieved with similar concentrations (approximately 1 μM from the respective compound to reach saturation response), again indicating similar binding affinities of the three compounds. The maximal fold activation by 1 and 2, however, was severalfold lower than by the full agonist pioglitazone, indicating a partial agonism of the neolignans in this test system.

Fig. 3.

Influence of the neolignans on the hPPARγ-mediated reporter gene transactivation. HEK-293 cells, transiently cotransfected with a plasmid encoding full-length hPPARγ, a reporter plasmid containing PPRE coupled to a luciferase reporter, and EGFP as internal control, were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of the respective compounds for 18 h. Luciferase activity was normalized by the EGFP-derived fluorescence, and the result was expressed as fold induction compared with the negative control (DMSO vehicle treatment). The data shown are means ± S.D. of three independent experiments each performed in quadruplet.

PPARγ Coactivator Recruitment

The binding of ligands to the PPARγ LBD results in a conformational change of the receptor and subsequent recruitment of coactivator proteins (TRAP220, SRC-1, CBP, p300, PGS-1, and/or others), that contribute to the transcriptional regulation of the different PPAR-responsive promoters (Yu and Reddy, 2007). To assess whether the lower maximal activation achieved by the neolignans in the luciferase reporter gene assay might be due to differences in the coactivator recruitment potential of the formed ligand-receptor complex, we next performed a TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment assay.

As shown in Fig. 4, compounds 1 to 3 indeed induced just a partial recruitment of the fluorescein-labeled TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator peptide to the PPARγ LBD, whereas the known full PPARγ agonist pioglitazone induced a severalfold stronger activation. As expected, compound 4 again was not active. In agreement with the result from the luciferase reporter gene assay, the concentration range needed for a saturation response was highly similar for compounds 1 to 3 and pioglitazone. However, the maximal activation induced with the full agonist pioglitazone was again several times higher.

Fig. 4.

Influence of neolignans on PPARγ coactivator recruitment. The ability of the hPPARγ-ligand complex formed with the test compounds to recruit the TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator peptide was measured as described in detail under Materials and Methods. Serial dilutions of the tested compounds were prepared in DMSO and then mixed with a buffer solution containing the hPPARγ LBD tagged with GST, terbium-labeled anti-GST antibody, and fluorescein-labeled TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator peptide. After incubation for 1 h, the emission at 520 and 495 nm after excitation at 340 nm was measured, and the 520 nm/495 nm ratio was used as a measure for the TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment potential of the respective compounds. Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Taken together, the data obtained from the receptor binding, the luciferase reporter gene transactivation, and the coactivator recruitment are indicating that the neolignans 1 to 3 are binding to the PPARγ LBD with a high affinity, in a concentration range similar to that of the clinically used agonist pioglitazone. The conformation of the ligand-receptor complex formed with compounds 1 to 3, however, is different from the one induced with the full agonist pioglitazone; consequently, the neolignans exhibit partial agonism with respect to TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment and tk-PPREx3 promoter activation.

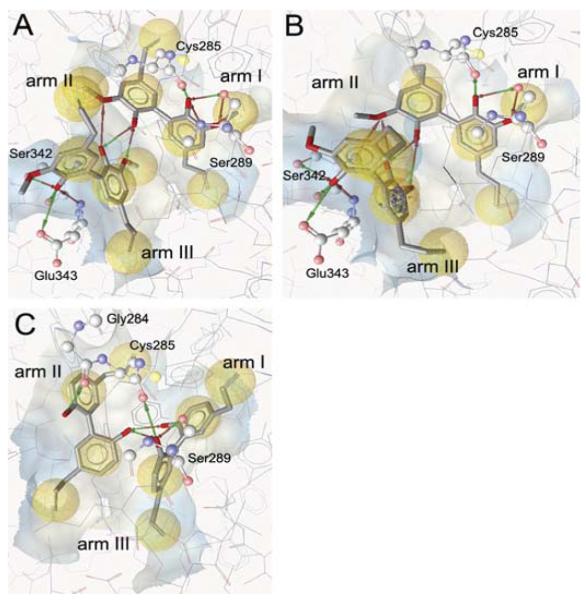

Molecular Docking

To get a deeper mechanistic understanding of the binding of compounds 1 to 3 to the PPARγ ligand binding pocket, we examined the putative binding modes of these ligands in silico by docking them into the hPPARγ binding pocket. The initial docking of compounds 1 to 3 to the PPARγ binding pocket showed that these small PPARγ ligands occupy only a minor part of the large ligand binding pocket, and thus leave space and hydrogen bond possibilities for a second ligand. Itoh et al. (2008) crystallized a PPARγ-ligand complex containing a fatty acid bound to the ligand binding pocket in a dimeric way. Based on this new information, we have assumed for our docking studies that the agonistic activity of 1 to 3 is caused by the simultaneous binding of two copies of this ligand to the binding site. From docking compound 1 into the PPARγ ligand binding pocket twice, several hydrogen bonds between the two dieugenol ligands and the binding site can be observed (Fig. 5A). Ser289 and Cys285 form a hydrogen bond network with one 2-methoxyphenol moiety of the molecule of 1 that is located next to arm I, as visualized in Fig. 5A. The second part of the ligand dimer establishes several hydrogen bonds between residues Ser342 and Glu343 and one of its 2-methoxyphenol moieties. The other 2-methoxyphenol group of this copy of 1 is involved in a hydrogen bond network formed between both ligands. In addition, the vinyl, phenyl, and methoxy moieties of both molecules established hydrophobic contacts to the binding pocket.

Fig. 5.

Putative interactions between the hPPARγ binding pocket and the neolignans 1 (A), 2 (B), and 3 (C). The docking results were visualized using the LigandScout software with the following color code: hydrogen bond acceptor (red arrow), hydrogen bond donor (green arrow), hydrophobic interaction (yellow sphere) and aromatic interaction (blue rings). The ligand binding pocket was depicted as surface colored based on the hydrophilicity/lipophilicity.

Next, two molecules of 2 were docked to the ligand binding pocket, which resulted in the prediction of a binding mode including similar protein-ligand interactions as described for 1 (Fig. 5B).

The best docking pose for compound 3 consisted of one copy of 3 located between arms I and III and the other part of the ligand dimer situated between arms II and III (Fig. 5C). The molecule of compound 3 oriented toward arm I forms hydrogen bonds between one hydroxyl group and residues Ser289 and Cys285. Both hydroxyl groups of this copy of 3 are involved in hydrogen bonding with one hydroxyl group of the second part of the dimer. The remaining hydroxyl group of the latter ligand formed another hydrogen bond to residue Gly284. In addition, both molecules establish several hydrophobic interactions with the three arms of the binding pocket.

Similar docking poses determined for compounds 1 and 2 show that the putative binding modes for both compounds include more interactions with the PPARγ binding pocket than the predicted binding mode for compound 3. This could be an explanation for the higher affinity of 1 and 2 compared with 3.

Selectivity of Action

We next studied whether the neolignans are activating PPARγ selectively over the other two PPAR subtypes. The subtype specificity of the assay was achieved by replacing the expression plasmid for hPPARγ with an expression plasmid for hPPARα and hPPARβ/δ (Table 1). Mouse PPARγ (mPPARγ) was also tested to exclude species differences that could modulate the effectiveness of neolignans in PPARγ experimental models from rodent origin, such as the 3T3-L1 cells that we used (Fig. 6). The specificity of the assays was verified with known selective agonists of PPARα (GW7647), PPARβ/δ (GW0742), and PPARγ (pioglitazone). Compounds 1 to 3 activated PPARγ 3.58-fold (with an EC50 of 0.62 μM), 3.34-fold (with an EC50 of 0.33 μM), and 3.03-fold (with an EC50 of 1.62 μM), respectively. Highly similar activation was seen with mPPARγ, suggesting that the neolignans also have very comparable potency of action with the rodent receptor. Compound 4 had no effect on any of the PPAR subtypes tested. The positive control for PPARγ, pioglitazone, induced an 8.05-fold activation (EC50 of 0.26 μM) with hPPARγ and a 6.80-fold activation (EC50 of 0.22 μM) with mPPARγ. It is noteworthy that compounds 1 and 2 activated PPARγ selectively with no effect on the other two PPAR subtypes. Compound 3 was not equally specific, because it was activating also hPPARβ/δ at higher concentrations.

TABLE 1.

Selectivity of the neolignans toward PPAR subtype (-α, -β/δ, -γ)-driven luciferase reporter transactivation HEK-293 cells were transiently cotransfected with an expression plasmid for the respective PPAR subtype, a reporter plasmid containing PPRE coupled to the luciferase reporter, and EGFP as internal control. Cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of the respective compounds for 18 h. Luciferase activity was normalized by the EGFP-derived fluorescence, and the result was expressed as fold induction compared with the negative control (DMSO vehicle treatment). The selective agonists for PPARα (GW7647), PPARβ/δ (GW0742), and PPARγ (pioglitazone) were used to verify the specificity of the respective assays. EC50 and maximal fold activation were determined by GraphPad Prism using settings for nonlinear regression with sigmoidal dose response and variable slope. The data shown represent means of three to five independent experiments, each performed in quadruplet. Analysis of variance showed statistical significance with P < 0.001 for the presented effects.

| hPPARα |

hPPARβ/δ |

hPPARγ |

Mouse PPARγ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | Maximal Fold Activation |

EC50 | Maximal Fold Activation |

EC50 | Maximal Fold Activation |

EC50 | Maximal Fold Activation |

|

| μM | μM | μM | μM | |||||

| GW7647 | 0.0016 | 3.09 | ||||||

| GW0742 | 0.0015 | 22.47 | ||||||

| Pioglitazone | 0.26 | 8.05 | 0.22 | 6.80 | ||||

| Dieugenol (1) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.62 | 3.58 | 0.93 | 2.93 |

| Tetrahydrodieugenol (2) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0.33 | 3.34 | 0.38 | 2.98 |

| Magnolol (3) | N.D. | N.D. | 11.41 | 2.45 | 1.62 | 3.03 | 1.14 | 2.81 |

| Eugenol (4) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

N.D., not detected up to 100 μM.

Fig. 6.

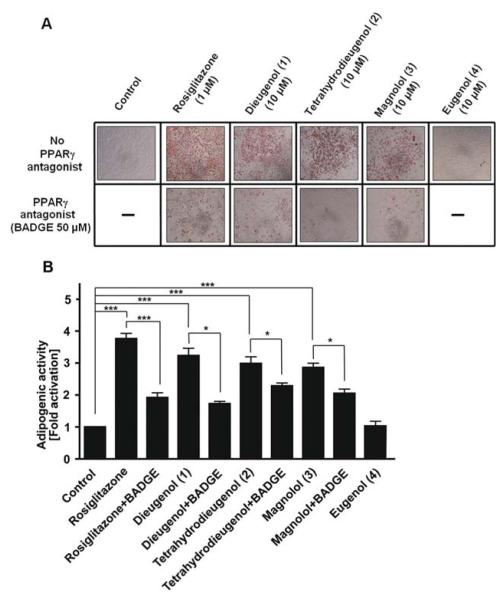

Adipogenic activity of compounds 1 to 4. A, 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were differentiated to adipocytes as described in the Materials and Methods section. After 7 to 8 days of differentiation with the indicated test compounds (1 μM rosiglitazone, 50 μM BADGE, and 10 μM neolignans, respectively), Oil Red O staining was performed to clearly visualize the accumulated lipids. Representative photos of one experiment of three with consistent results are depicted. B, to get a quantitative measure, the dye accumulated in the cells (treated as described under A) was solubilized by 100% isopropanol and photometrically quantified at 550 nm. The data shown are means ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001, as estimated by two-tailed paired t test.

Adipocyte Differentiation

We next aimed to confirm the effectiveness of the neolignans in a functionally relevant cell model with endogenous expression of PPARγ. Because it is known that PPARγ is an essential player in adipocyte differentiation (Rosen et al., 1999), we examined the adipogenic potential of 1 to 4 in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. As positive control, we chose rosiglitazone (1 μM), the most often used control TZD in this model (Fig. 6, A and B) (Wright et al., 2000). As evident by the accumulation of lipid droplets and subsequent Oil Red staining, the treatment with 10 μM compounds 1 to 3 resulted in the differentiation to adipocytes, whereas compound 4 had no adipogenic activity (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the PPARγ antagonist BADGE (Wright et al., 2000) significantly reduced the adipogenic potential of compounds 1 to 3 and the positive control rosiglitazone, demonstrating the PPARγ dependence of the observed effect (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

Here we show the identification of several neolignans that act as partial PPARγ agonists using an in silico approach, including a pharmacophore-based virtual screening of the natural product databases DIOS and CHM (Rollinger et al., 2008).

The affinity of the virtual hits for the hPPARγ LBD was experimentally confirmed in a PPARγ competitive ligand binding assay (Fig. 2). Compounds 1 to 3 potently bind to the receptor LBD in a concentration range similar to that of the clinically used PPARγ agonist pioglitazone. Based on these promising in vitro results we further verified the ability of these neolignans to activate PPARγ also in a cellular model. Indeed, compounds 1 to 3 dose dependently activated hPPARγ in a HEK-293 cell-based luciferase reporter gene transactivation model (Fig. 3). The concentrations of compounds 1 to 3 needed to reach a saturation response were similar to that of pioglitazone, again indicating a similar affinity to the PPARγ receptor binding pocket. The maximal activation reached by pioglitazone, however, was severalfold higher, indicating that the neolignans are acting as partial PPARγ agonists in this model. It is well known that different PPAR ligands might form ligand-receptor complexes with different coactivator recruitment potentials and thus different transactivation properties. Therefore, we studied the TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment properties of the PPARγ-ligand complexes induced by the neolignans compared with the known full agonist pioglitazone (Fig. 4). The neolignans 1 to 3 again acted as partial agonists, because the maximal activation was severalfold lower than the activation induced by the full TZD agonist. Thus, compared with pioglitazone, the neolignans 1 to 3 possess a similar affinity to PPARγ but apparently induce a receptor-ligand complex with a different conformation, leading to partial agonism. TZDs that are currently clinically used as PPARγ activators are potent full agonists of PPARγ. To avoid the undesired side effects of TZDs, the development of novel partial PPARγ agonists was suggested as a highly promising approach (Yumuk, 2006; Chang et al., 2007). Thus, MBX-102 (metaglidasen), a selective partial PPARγ agonist, exhibiting a weaker transactivation activity and a reduced coactivator recruitment potential, was recently reported to retain antidiabetic properties in the absence of weight gain and edema (Gregoire et al., 2009). The activation pattern of the neolignans, therefore, makes them a highly interesting class of PPARγ activators.

In all systems used, compounds 1 and 2 had the highest potency among the tested neolignans, followed closely by 3, whereas 4 had no activity. To get a deeper insight into the binding mode of the neolignans to the hPPARγ LBD, we used molecular docking (Fig. 5). The docking studies assume the neolignans to bind as dimers to the receptor binding pocket, and reveal 1 and 2 to make more interactions with the PPARγ binding pocket than 3, underlining the higher activity observed with these compounds.

Compounds 1 and 2 selectively activated hPPARγ but not hPPARβ/δ or hPPARα (Table 1). This is another favorable profile of action because all PPARγ agonists that are currently approved on the market are isoform-specific PPARγ activators. There are, however, some experimental indications that PPAR dual agonists or pan-agonists might also provide advantages (Chang et al., 2007).

Because the PPAR luciferase reporter gene assay represents an artificial cell model with transient overexpression of PPARγ, we examined all neolignans for their ability to differentiate 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which is a functionally relevant cell model making use of endogenously expressed PPARγ. In line with the results from all other models, 1 to 3 induced adipocyte differentiation and their activity was abolished by the PPAR antagonist BADGE. Compound 4, however, was not active, again confirming the results from all previous experimental models as well as the predictions from the molecular docking studies.

In addition to our findings shown here, the compounds dieugenol (1) and tetrahydrodieugenol (2) have been reported previously to act as antioxidants (Ogata et al., 2000), antimutagenics (Miyazawa and Hisama, 2003), and to exert anti-inflammatory activity (Murakami et al., 2003). Magnolol (3) is a prominent constituent of the traditional Chinese herbal remedy magnolia bark (hòu pò) (Bensky et al., 2004). From a Western perspective, magnolia bark was suggested to be among the herbal drugs effective in combating metabolic syndrome (Baños et al., 2008). In a recent study, treatment with magnolol decreased fasting blood glucose and plasma insulin levels and was able to prevent or retard the pathological complications in type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats (Sohn et al., 2007). A recent report also showed that magnolol enhances adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells and C3H10T1/2 cells, and suggested that these effects might be due to PPARγ modulation (Choi et al., 2009). Here we show that magnolol indeed activates PPARγ in several in vitro or cell-based models, but, distinct from 1 and 2, it acts as a dual agonist also activating PPARβ/δ at higher concentrations (Table 1). Although magnolol was not the most potent and specifically acting neolignan in our study, its PPAR activating potential is of interest, because it fits well to the traditional use of magnolia bark as an herbal drug combating metabolic disorders.

In summary, we describe the computer-aided discovery of several neolignans as novel ligands of PPARγ. In receptor binding assays, dieugenol (1) and tetrahydrodieugenol (2) exhibited a higher affinity for PPARγ than the clinically used agonist pioglitazone (Actos). Furthermore, 1 and 2 were identified as selective activators of PPARγ, but not of PPARα or PPARβ/δ. Compared with the TZD pioglitazone, 1 and 2 displayed a partial agonism with respect to PPARγ luciferase reporter gene transactivation and TRAP220/DRIP-2 coactivator recruitment. In addition, they induced adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells PPARγ-dependently. The activation pattern exhibited from 1 and 2 makes them highly interesting novel PPARγ agonists, having the potential to be further explored as leads for the development of novel pharmaceuticals or dietary supplements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Walter Wahli and Prof. Beatrice Desvergne for providing the PPAR expression plasmids and Prof. Ronald M. Evans for providing the PPRE luciferase reporter construct. We thank Elisabeth Geiger, Daniel Schachner, and Judith Benedics for excellent technical support.

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [Grants NFN S10704-B03, S10702-B03, S10703-B03] and the Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research [Grants ACM-2007-00178, ACM-2008-00857, and ACM-2009-01206].

ABBREVIATIONS

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- PPRE

PPAR response element

- TZD

thiazo-lidinedione

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- h

human

- 3D

three-dimensional

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- GW7647

2-(4-(2-(1-cyclohexanebutyl)-3-cyclohexylureido)ethyl)phenylthio)-2-methylpropionic acid

- GW0742

4-[2-(3-fluoro-4-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-4-methyl-thiazol-5-ylmethylsulfanyl]-2-methyl-phenoxy}-acetic acid

- BADGE

bisphenol A diglycidyl ether

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- TR-FRET

time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- MBX-102

metaglidasen

- GST

glutathione transferase

Footnotes

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

References

- Anghel SI, Wahli W. Fat poetry: a kingdom for PPAR gamma. Cell Res. 2007;17:486–511. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baños G, Pérez-Torres I, El Hafidi M. Medicinal agents in the metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6:237–252. doi: 10.2174/187152508785909465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardot O, Aldridge TC, Latruffe N, Green S. PPAR-RXR heterodimer activates a peroxisome proliferator response element upstream of the bifunctional enzyme gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:37–45. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedu E, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta as a therapeutic target for metabolic diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:861–873. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensky D, Clavey S, Stöger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine–Materia Medica. Eastland Press, Inc.; Seattle, WA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Jaber LA, Berlie HD, O’Connell MB. Evolution of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:973–983. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho N, Momose Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists as insulin sensitizers: from the discovery to recent progress. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8:1483–1507. doi: 10.2174/156802608786413474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SS, Cha BY, Lee YS, Yonezawa T, Teruya T, Nagai K, Woo JT. Magnolol enhances adipocyte differentiation and glucose uptake in 3T3–L1 cells. Life Sci. 2009;84:908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvergne B, Michalik L, Wahli W. Transcriptional regulation of metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:465–514. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchart JC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARalpha): at the crossroads of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire FM, Zhang F, Clarke HJ, Gustafson TA, Sears DD, Favelyukis S, Lenhard J, Rentzeperis D, Clemens LE, Mu Y, et al. MBX-102/JNJ39659100, a novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-ligand with weak transactivation activity retains antidiabetic properties in the absence of weight gain and edema. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:975–988. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurnell M. ‘Striking the Right Balance’ in Targeting PPARgamma in the Metabolic Syndrome: Novel Insights from Human Genetic Studies. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:83593. doi: 10.1155/2007/83593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Fairall L, Amin K, Inaba Y, Szanto A, Balint BL, Nagy L, Yamamoto K, Schwabe JW. Structural basis for the activation of PPARgamma by oxidized fatty acids. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:924–931. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu IL, Huang CF, Peng YH, Lin YT, Hsieh HP, Chen CT, Lien TW, Lee HJ, Mahindroo N, Prakash E, et al. Structure-based drug design of a novel family of PPARγ partial agonists: virtual screening, x-ray crystallography, and in vitro/in vivo biological activities. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2703–2712. doi: 10.1021/jm051129s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquet S, Gaudel C, Holst D, Lopez-Soriano J, Jehl-Pietri C, Fredenrich A, Grimaldi PA. Roles of PPAR delta in lipid absorption and metabolism: a new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markt P, Petersen RK, Flindt EN, Kristiansen K, Kirchmair J, Spitzer G, Distinto S, Schuster D, Wolber G, Laggner C, et al. Discovery of novel PPAR ligands by a virtual screening approach based on pharmacophore modeling, 3D shape, and electrostatic similarity screening. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6303–6317. doi: 10.1021/jm800128k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markt P, Schuster D, Kirchmair J, Laggner C, Langer T. Pharmacophore modeling and parallel screening for PPAR ligands. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:575–590. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marque FA, Simonelli F, Oliveira ARM, Gohr GL, Leal PC. Oxidative coupling of 4-substituted 2-methoxy phenols using methyltributylammonium permanganate in dichloromethane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:943–946. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M, Hisama M. Antimutagenic activity of phenylpropanoids from clove (Syzygium aromaticum) J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:6413–6422. doi: 10.1021/jf030247q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y, Shoji M, Hanazawa S, Tanaka S, Fujisawa S. Preventive effect of bis-eugenol, a eugenol ortho dimer, on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated nuclear factor kappa B activation and inflammatory cytokine expression in macrophages. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Hoshi M, Urano S, Endo T. Antioxidant activity of eugenol and related monomeric and dimeric compounds. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48:1467–1469. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachez C, Gamble M, Chang CP, Atkins GB, Lazar MA, Freedman LP. The DRIP complex and SRC-1/p160 coactivators share similar nuclear receptor binding determinants but constitute functionally distinct complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2718–2726. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2718-2726.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizos CV, Elisaf MS, Mikhailidis DP, Liberopoulos EN. How safe is the use of thiazolidinediones in clinical practice? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8:15–32. doi: 10.1517/14740330802597821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinger JM, Steindl TM, Schuster D, Kirchmair J, Anrain K, Ellmerer EP, Langer T, Stuppner H, Wutzler P, Schmidtke M. Structure-based virtual screening for the discovery of natural inhibitors for human rhinovirus coat protein. J Med Chem. 2008;51:842–851. doi: 10.1021/jm701494b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, Spiegelman BM, Mortensen RM. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn EJ, Kim CS, Kim YS, Jung DH, Jang DS, Lee YM, Kim JS. Effects of magnolol (5,5′-diallyl-2,2′-dihydroxybiphenyl) on diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Life Sci. 2007;80:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum A, Fisman EZ, Motro M. Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus: focus on peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPAR) Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2003;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolber G, Dornhofer AA, Langer T. Efficient overlay of small organic molecules using 3D pharmacophores. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2006;20:773–788. doi: 10.1007/s10822-006-9078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolber G, Langer T. Comb(i)Gen: a novel software package for the rapid generation of virtual combinatorial libraries. In: Höltje HD, Sippl W, editors. Rational Approaches to Drug Design. Prous Science; Barcelona: 2001. pp. 390–399. [Google Scholar]

- Wolber G, Langer T. LigandScout: 3-D pharmacophores derived from protein-bound ligands and their use as virtual screening filters. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45:160–169. doi: 10.1021/ci049885e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright HM, Clish CB, Mikami T, Hauser S, Yanagi K, Hiramatsu R, Serhan CN, Spiegelman BM. A synthetic antagonist for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1873–1877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahara S, Nishiyori T, Kohda A, Nohara T, Nishioka I. Isolation and characterization of phenolic compounds from magnoliae cortex produced in China. Chem Pharm Bull. 1991;39:2024–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Reddy JK. Transcription coactivators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:936–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumuk VD. Targeting components of the stress system as potential therapies for the metabolic syndrome: the peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1083:306–318. doi: 10.1196/annals.1367.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.