Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between corneal hysteresis (CH) and the corneal resistance factor (CRF), which are both novel methods of analyzing ocular rigidity/elasticity, and various corneal characteristics, mainly corneal volume in normal subjects.

METHODS:

This cross-sectional study included 500 normal eyes of volunteers. An ocular response analyzer (ORA) was used to measure CH and CRF. Patient age and the Pentacam-measured corneal volume (CV), posterior elevation, anterior elevation, corneal curvature, central corneal thickness (CCT), corneal thickness of apex (CTA), and corneal thinnest thickness (CTT) were compared with CH and CRF. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05.

RESULTS:

The mean CH and CRF for all eyes were 9.9 ± 1.4 mmHg and 10.1 ± 1.6 mmHg, respectively. The mean CVs of the 3, 5, 7, and 10 mm zones for all eyes were 3.8 ± 0.2 mm3, 11.2 ± 0.6 mm3, 24.3 ± 1.4 mm3, and 60.1 ± 3.5 mm3, respectively. The correlations between CV and the hysteresis or CRF were significant in all zones. The CV of the 7-mm zone had the strongest correlation with CH (r = 0.438) and the CV of the 5-mm zone had the strongest correlation with CRF (r = 0.574).

CONCLUSIONS:

CH and CRF correlate with CV. Moreover, the correlation between CV and CRF is stronger than that between CV and CH. The CV may be valuable for determining patient's qualification for and predicting the outcome of refractive surgery. It would also be helpful in other cases in which corneal biomechanics are important.

KEYWORDS: Cornea, Corneal Biomechanics, Corneal Resistance Factor, Corneal Hysteresis, Ocular Response Analyz-er, Pentacam, Corneal Volume, Corneal Thickness

With the recent heightened interest in corneal refractive surgical procedures, which result in substantial changes in the corneal tissue structure, a greater understanding of the interrelationships among the biomechanical properties of the cornea has increasingly become important. Such knowledge would minimize damage to the corneal tissue.1

Recently, Reichert Ophthalmic Instruments (NY, USA) developed the ocular response analyzer (ORA) as an adaptation of their non-contact tonometer. This device measures the intraocular pressure (IOP) and two new properties, the corneal hysteresis (CH) and corneal resistance factor (CRF).2,3 An air puff, released from the ORA, causes an inward and then an outward corneal motion that provides two applanation measurements during a single measurement process. Hysteresis may reflect the result of corneal damping because of its viscoelastic properties. It is derived from the difference between the two applanation measurements. While CRF is a function of the same two parameters as CH, i.e. the first and second applanation pressures, it is also influenced by the viscoelastic response. Since it was designed to have the maximal correlation with corneal thickness, it is influenced more than CH by elastic properties. In addition, CH and CRF are highly correlated.4

Among the numerous morphologic parameters that can be measured by modern examination techniques is the corneal volume (CV). It reflects topographical and pachymetric changes and characterizes corneal morphometric changes with a single value.5 Pentacam (Oculus, Dutenhofen, Germany), a new 3-dimensional analyzer equipped with a rotating Scheimpflug camera, allows CV assessment.6 Because the CV is a numerical value, it may be useful for a statistical assessment of the entire cornea.

The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between CH and CRF, which are novel methods of analyzing ocular rigidity/elasticity, and various corneal characteristics in normal subjects. As CH and CRF are said to be related with corneal biomechanical properties, they may have relations with corneal parameters that are nowadays best evaluated by Scheimpflug camera techniques, like using Pentacam. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the relationship among these parameters in normal eyes.

Methods

A total of 500 normal eyes of 500 patients (138 males and 362 females) were revaluated. Patients were recruited from among those attending Toos Ophthalmology Clinic in Mashhad, Iran for refractive surgery since March 2007 to March 2008. All of them were evaluated by an anterior segment subspecialist ophthalmologist to have normal eyes on history and examination, except for refractive error. Exclusion criteria were age more than 35 years or less than 20 years, any corneal pathology like keratoconus, corneal dystrophy, and an irregular corneal topography pattern. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences) and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

CH and CRF values were measured using the ORA while the subject was sitting comfortably in a chair. The patient was asked to look at a fixed target (a red blinking light) in the ORA. The ORA was activated by pressing a button attached to the computer. A non-contact probe released an air puff. A signal of air reflux was sent to the ORA, which displayed the IOP, CH, and CRF on the computer monitor. The CH and CRF values of eyes were measured three times for each eye and the average measurement was documented for each eye.

A rotating Scheimpflug camera (Pentacam) was used to determine the CVs at 3, 5, 7, and 10 mm zones from the central cornea, as well as the posterior and anterior elevation, corneal radius of curvature, central corneal thickness (CCT), corneal thickness of apex (CTA), and corneal thinnest thickness (CTT). To measure the corneal thickness (CT), the patient was seated using a chinrest and forehead strap and was asked to look at a fixed target for about 1.5-2 seconds as the Scheimpflug camera rotated. The CT values at the thinnest point and of the apex were also recorded for each eye. All the measurements were performed by the same observer.

Data was analyzed using SPSS13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive data is reported as mean ± SD. A correlation (bivariant) test was performed to assess the relationship between the parameters. Statistical significance was defined at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

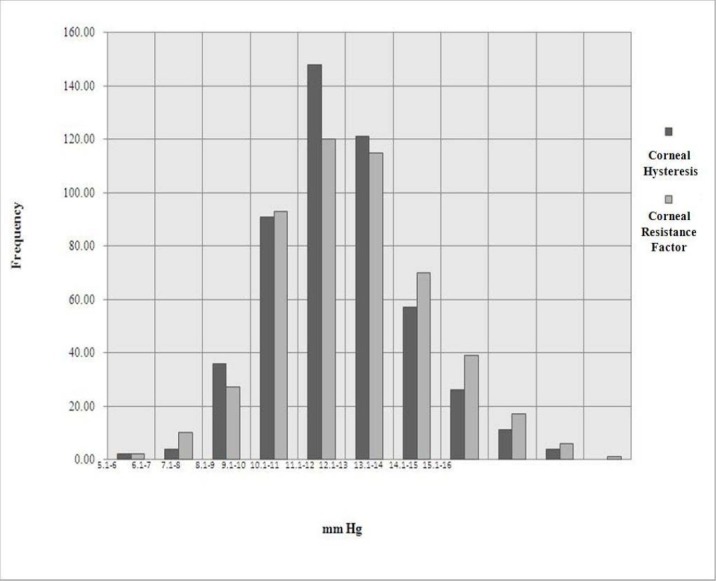

The mean (mean ± SD) age of patients involved in this study was 29.3 ± 6.9 years (range: 18-59 years). The mean values of CH and CRF for all eyes were 9.9 ± 1.4 mmHg (range: 5.1-14.9 mmHg) and 10.1 ± 1.6 mmHg (range 5.7-15.2 mmHg), respectively. Figure 1 demonstrates the frequency distribution of CH and CRF among all eyes. Age was not signifycantly associated with the CH or CRF.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of corneal hysteresis (CH) and corneal resistance factor (CRF) among all eyes * The horizontal line depicts the CH and CRF in mmHg while the vertical line depicts the distribution of the patients’ frequencies

The mean CV value of the 3, 5, 7, and 10 mm zones for all eyes were 3.8 ± 0.2 mm3 (range: 2.9-4.6 mm3), 11.2 ± 0.6 mm3(range: 9.2- 13.4 mm3), 24.3 ± 1.4 mm3(range: 20.9-29.1 mm3), and 60.1 ± 3.5 mm3 (range: 51.2-71.2 mm3), respectively.

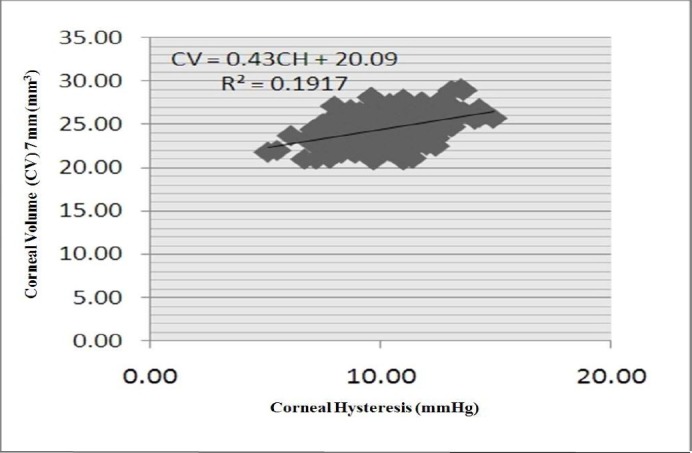

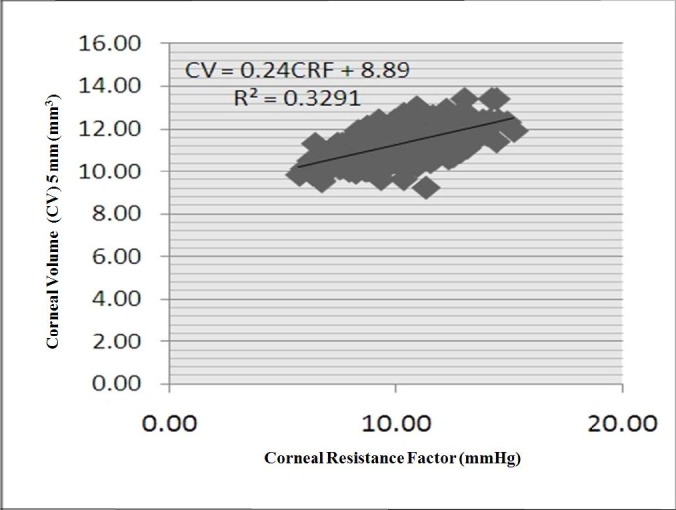

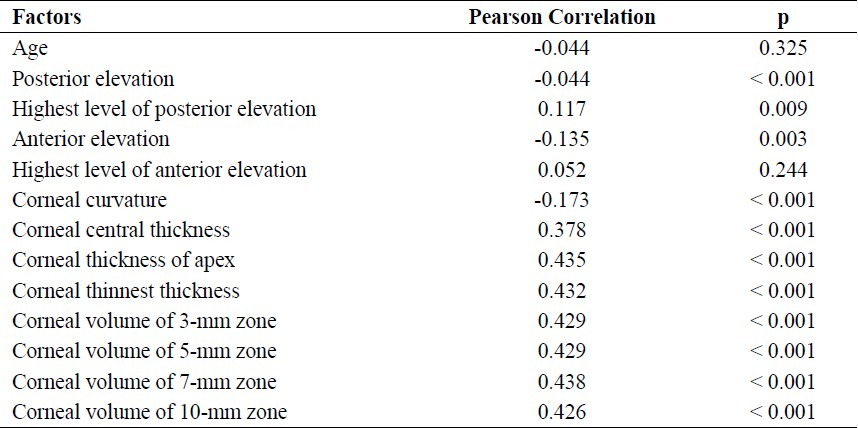

There was a statistically significant relationship between CV and CH or CRF in all zones. The CV of the 7-mm zone had the strongest correlation with CH (r = 0.438) (Figure 2), and the CV of the 5-mm zone had the strongest correlation with CRF (r = 0.574) (Figure 3). Correlations among CH, CRF, and CVs in all other areas are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The relationship between CRF and the CVs was stronger than that between CH and the CVs.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of correlation between corneal hysteresis (CH) and corneal volume 7-mm (CV.7)

* The horizontal line depicts the CH distribution in mmHg. The correlation between CH and of CV. 7 mm (in mm3) distributions is shown.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of the correlation between corneal resistance factor (CRF) and corneal volume 5 mm (CV.5).

* The CRF distribution in mmHg is depicted on the horizontal line and its correlation with the distribution of CV.5 mm in mm3 scale is shown.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between corneal hysteresis (CH) and the studied parameters

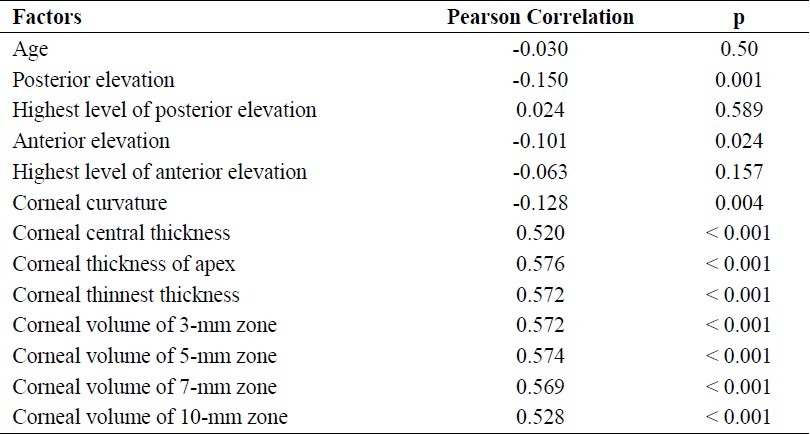

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between corneal resistance factor (CRF) and the studied parameters

The mean values of CCT, CTA, and CTT among all eyes were 534.26 ± 34.96 μm (range: 391.0-793.0 μm), 533.80 ± 33.10 μm (range: 391.0-636.0 μm), and 531.43 ± 33.14 μm (range: 391.0-632.0 μm), respectively. All of the relationships between CCT, CTA, CTT, and CH were statistically significant. The correla-tion between CTA and CH, which displayed only a moderate correlation coefficient (r = 0.435), was stronger than that between other variables (Table 1). All of the relationships among CCT, CTA, CTT, and CRF were also statistically significant. The correlation between CTA and CRF (r = 0.576) was stronger than that between other variables (Table 2).

The mean corneal radius of curvature among all eyes was 7.64 ± 0.27 mm (range: 6.73-8.96). Inverse relationships were seen between corneal radius of curvature and CH (r = -0.173) and CRF (r = -0.128), but the correlation coefficients were low. Significant inverse relationships were also seen between CH and the anterior elevation in central 3 mm (r = -0.135) and posterior elevation in central 3 mm (r = -0.186), but the correlation coefficients were again low. The same was true for the relationship between CRF and the anterior and posterior elevation (r = -0.101 and r = -0.150, respectively) (Tables 1 and 2).

Discussion

In this study, we used the ORA to measure the CH and CRF in 500 normal eyes. We also determined their relationship with CV, age, posterior elevation, anterior elevation, corneal curvature, and CCT. Based on our findings, CH and CRF were moderately correlated with the CV, posterior elevation, anterior elevation, corneal curvature, and CT measured by Pentacam. In each patient, only one eye was examined and enrolled in the study. The CCT, CTA, CTT, CV, and posterior elevation were more strongly correlated with CRF than with CH. Finally, the CVs of the 7-and 5-mm zones were more important than those of the other zones (Tables 1 and 2).

Due to their influence on refractive surgery outcomes, studies of corneal biomechanics have become increasingly common.7–11 The human cornea is a viscoelastic tissue4,11 that can be described by two principal properties including a static resistance component for which deformation is proportional to applied force and may be related to CRF and a dynamic resistance component characterized by CH for which the relationship between deformation and applied force depends on time. In short, the tissue response in the presence of a force depends not only on the force magnitude but also on the velocity of the force application.12

Several previous studies have investigated corneal biomechanical properties, including the CH and CRF measured by the ORA. The CH was first measured on the ORA by Luce who reported ocular hysteresis in normal, keratoconic, Fuchs’ dystrophy, and postlaser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) patients from pooled data of a large number of users and machines. The hysteresis varied over a dynamic range of 1.8-14.6 mmHg.4 Ortiz et al. found that the CH and CRF values were lower in keratoconic eyes than in post-LASIK eyes.13 Consistent with other clinical reports, a clinical study by Glass et al. found that low hysteresis values can be associated with either high or low elasticity depending on the viscosity.14 In 2008, Touboul et al. analyzed the correlation between CH and the ultrasonic CCT and IOP measured by Goldmann applanation tonometry. They concluded that low CH can be considered as a risk factor for IOP underestimation.15 Kotecha et al. found a new parameter that appeared to be IOP-independent that increased with thicker CCT and decreased with greater age. The factor was strongly associated with CCT, and yet explained more of the interindividual variation in Goldmann applanation tonometry IOP than did CCT. Normalized ORA IOP measurements were not associated with CCT.16

Liu et al. performed a clinical analysis to investigate the CH and CRF in normal eyes. Similar to our results, The CH and CRF significantly correlated with CCT and the corneal curvature, but not with age. They reported that CH and CRF measure different biomechanical aspects of the cornea and may reflect the combined effect of CCT, corneal curvature, rigidity, hydration, and IOP.17 Their CH and CRF values for normal eyes established guidelines for further investigations of their relationship with eye disease.

In 2006, Shah et al. investigated the relationships between CH and CRF and CCT. Similar to our study results, they demonstrated that CH moderately increased with increasing CCT.2 In 2009, Shah et al. clinically compared corneal biomechanical parameters and two measures of IOP in eyes before and after excimer laser refractive surgery. The CH and CRF decreased after both myopic and hyperopic CV as it has the stronger relations with CRF refractive surgery.3

Fontes et al. have shown that the values for CH, CRF, CV, and CCT were statistically lower in patients with keratoconus in contrast with their matched controls. However, in this study, the correlation was not evaluated.18 Mannion et al. have found that CV was significantly decreased in keratoconus, particularly in the central and paracentral area explained by loss of corneal tissue. The reduction in corneal volume was in moderate and severe cases of keratoconus, but not in the early cases. This reduction in CV was not related to the CCT, although CCT was decreased in all groups.19

In conclusion, this was the first study to determine the relationship between ocular hysteresis, CRF, and CV in normal eyes. However, it has been demonstrated that the repeatability of the ORA is low. In addition, CH values have been reported to be the most variable measure.17 Therefore, it is better to interpret the results with some caution. We focused more on CV as it has the stronger relations with CRF and CH. Other corneal parameters were also evaluated in this study. Moreover, because the CV, CH, and CRF may measure different biomechanical aspects of cornea, we recommend using the CV as a useful additional measurement before refractive surgery. The CV may prove valuable for qualifying patients for refractive surgery, predicting patient outcomes, and in other cases in which corneal biomechanics are important.

A limitation in this study was the small number of the patients. Moreover, comparing the ORA findings with other Pentacam measured values should be performed. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to fully confirm these findings.

Authors’ Contributions

MRS designed and coordinated the study, participated in most of the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. MS provided assistance in the design of the study and participated in statistical evaluation and manuscript preparation. SH provided assistance for all experiments, especially in statistical analysis and manuscript preparation. MA assisted in data gathering and participated in manuscript preparation and editing. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Vice Chancellor of Research of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (No. 86738). However, the university had no role in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Hjortdal JO, Jensen PK. In vitro measurement of corneal strain, thickness, and curvature using digital image processing. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 1995;73(1):5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1995.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah S, Laiquzzaman M, Cunliffe I, Mantry S. The use of the Reichert ocular response analyser to establish the relationship between ocular hysteresis, corneal resistance factor and central corneal thickness in normal eyes. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2006;29(5):257–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah S, Laiquzzaman M, Yeung I, Pan X, Roberts C. The use of the Ocular Response Analyser to determine corneal hysteresis in eyes before and after excimer laser refractive surgery. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2009;32(3):123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luce DA. Determining in vivo biomechanical properties of the cornea with an ocular response analyzer. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(1):156–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervino A, Gonzalez-Meijome JM, Ferrer-Blasco T, Garcia-Resua C, Montes-Mico R, Parafita M. Determination of corneal volume from anterior topography and topographic pachymetry: application to healthy and keratoconic eyes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29(6):652–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2009.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki H, Takahashi H, Hori J, Hiraoka M, Igarashi T, Shiwa T. Phacoemulsification associated corneal damage evaluated by corneal volume. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(3):525–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant MR, McDonnell PJ. Constitutive laws for biomechanical modeling of refractive surgery. J Biomech Eng. 1996;118(4):473–81. doi: 10.1115/1.2796033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katsube N, Wang R, Okuma E, Roberts C. Biomechanical response of the cornea to phototherapeutic keratectomy when treated as a fluid-filled porous material. J Refract Surg. 2002;18(5):S593–S597. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20020901-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts C. Biomechanics of the cornea and wavefront-guided laser refractive surgery. J Refract Surg. 2002;18(5):S589–S592. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20020901-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamiya K, Miyata K, Tokunaga T, Kiuchi T, Hiraoka T, Oshika T. Structural analysis of the cornea using scanning-slit corneal topography in eyes undergoing excimer laser refractive surgery. Cornea. 2004;23(8 Suppl):S59–S64. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000136673.35530.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaycock PD, Lobo L, Ibrahim J, Tyrer J, Marshall J. Interferometric technique to measure biomechanical changes in the cornea induced by refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(1):175–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dupps WJ, Jr, Wilson SE. Biomechanics and wound healing in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(4):709–20. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz D, Pinero D, Shabayek MH, Arnalich-Montiel F, Alio JL. Corneal biomechanical properties in normal, post-laser in situ keratomileusis, and keratoconic eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(8):1371–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass DH, Roberts CJ, Litsky AS, Weber PA. A viscoelastic biomechanical model of the cornea describing the effect of viscosity and elasticity on hysteresis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(9):3919–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Touboul D, Roberts C, Kerautret J, Garra C, Maurice-Tison S, Saubusse E, et al. Correlations between corneal hysteresis, intraocular pressure, and corneal central pachymetry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(4):616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotecha A, Elsheikh A, Roberts CR, Zhu H, Garway-Heath DF. Corneal thickness- and age-related biomechanical properties of the cornea measured with the ocular response analyzer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(12):5337–47. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R, Chu RY, Wang L, Zhou XT. The measured value of corneal hysteresis and resistance factor with their related factors analysis in normal eyes. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2008;44(8):715–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontes BM, Ambrosio R, Jr, Jardim D, Velarde GC, Nose W. Corneal biomechanical metrics and anterior segment parameters in mild keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(4):673–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannion LS, Tromans C, O’Donnell C. Reduction in corneal volume with severity of keratoconus. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36(6):522–7. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2011.553306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]