Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Fully covered self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) placement has been successfully described for the treatment of malignant and benign conditions. The aim of this study is to evaluate our experience of fully covered SEMS placement for post-operative foregut leaks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Retrospective analysis was done for indications, outcomes and complications of SEMS placed in homogeneous population of 15 patients with post-operative foregut leaks in our tertiary-care centre from December 2008 to December 2010. Stent placement and removal, clinical and radiological evidence of leak healing, migration and other complications were the main outcomes analyzed.

RESULTS:

Twenty-three HANAROSTENT® SEMS were successfully placed in 14/15 patients (93%) with post-operative foregut leaks for an average duration of 28.73 days (range=1-42 days) per patient and 18.73 days per SEMS. Three (20%) patients needed to be re-stented for persistent leaks ultimately resulting in leak closure. Total 5/15 (33.33%) patients and 7/23 (30.43%) stents showed migration; 5/7 (71.42%) migrated stents could be retrieved endoscopically. There were mucosal ulceration in 2/15 (13.33%) and pain in 1/15 (6.66%) patients.

CONCLUSIONS:

Stenting with SEMS seems to be a feasible option as a primary care modality for patients with post-operative foregut leaks.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, endoscopic, fistulas, foregut surgery, post-operative leaks, self-expandable metallic stent

INTRODUCTION

In the last 30 years, as oesophageal stents have evolved in composition, so also have indications for their placement. SEMS have become a standard in palliation for dysphagia resulting from oesophageal and gastric cancers. Increasingly, fully covered self-expanding plastic stents and now fully covered metal stents have been used to treat a variety of benign oesophageal conditions as well as cancer.[1] One of the many indications for which the fully covered SEMS have been used recently is in the setting of post-surgical leaks. Oesophageal or gastric anastomotic leakage, perforation, staple line dehiscence or trauma can be a life-threatening scenario. There is a lack of standard protocol for their treatment. The spectrum of treatments suggested span from aggressive surgical re-exploration and repair or even disassembly of the anastomosis[2–4] to conservative treatment using total parenteral nutrition, peri-anastomotic drainage with chest or abdominal image-guided percutaneous drainage and broad spectrum antibiotics in selected patients. Re-operation is often not easy and associated with high morbidity and mortality. Enteral feeding started early during the treatment plays a significant role in leak closure.

Fully covered SEMS has been successfully used for the treatment of anastomotic leakage following esophagectomy for cancer,[5] after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass[6,7] and sleeve gastrectomy.[8–10] The endoscopically placed covered stents, by contributing to healing and early oral intake, improve symptoms, avoid morbid and costly procedures, and significantly decrease hospital stay.[6,11]

The aims of this study were to describe experience of successful placement of removable, fully covered SEMS in a homogeneous population of patients with post-operative foregut leaks and to review the current methods and technology of endoscopic stenting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

From 1st December 2008 to 1st December 2010, 15 patients were successfully stented for post-surgical foregut leaks.

Diagnosis and management

After the clinical suspicion, the foregut leak was diagnosed based on extravasation of contrast material during radiological examination such as esophagogram performed using a water-soluble contrast agent or computerised tomography (CT) scan (intravenous (IV) and oral contrast) or endoscopic visualization of leak. Patients received intensive care unit (ICU) care as per their general conditions and co-morbidities and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Stent placement

The endoscopic procedures were performed on patients under general anaesthesia with oral intubation within 24 hours of diagnosis of leak in the endoscopic unit or in the operating room during the surgical intervention. Fully covered SEMS (HANAROSTENT®-Life Partner Europe, France) was used. HANAROSTENT® consists of a membrane covering the nitinol tubular structure, gold radiopaque marker at both ends and at the centre. They come with a retrievable lasso each attached to proximal and distal ends and with or without an anti-reflux valve at a distal end. They are available in the lengths of 50-220 mm. The lasso attached at the proximal end makes it possible to adjust the proper positioning of the stent with forceps, if in case it slips distally. The traction on the stent causes it to elongate as it is pulled proximally. The HANAROSTENT® with an anti-reflux valve at the distal end can also prevent gastro-oesophageal reflux. Sizes of SEMS we placed ranged from 8-16 cm in length and 20-24 mm in diameter. After advancing the endoscope, the location of the leak was confirmed and the appropriate diameter, which will just snugly fit in the most constricted part of the lumen, and length of the stent, which will adequately cover the site of leak such that two-third of the stent remains proximal to the leak site, were selected under fluoroscopy guidance.

A guide wire was placed into the distal part of the viscera beyond the leak. Then, the scope was withdrawn. The stent was advanced over the guide wire through a delivery system of 6-8 mm diameter and 700 mm length and then deployed, controlling exactly the location, covering the leak, on fluoroscopy.

Post-stenting outcome

On the next day of stenting, if an esophagogram showed no leak, the patient was started with liquid diet. Antibiotic choice and percutaneous drainage were as per the patient's condition. Esophagograms were repeated if there were any worrisome symptoms. Endoscopy was avoided to prevent the risk of dislodging the stent. Patients were called for stent removal within 4 weeks. A control plain radiogram and a contrast esophagogram were performed before stent removal to locate it and to exclude persistent oesophageal leak. Using a standard single channel scope, the stents were removed by catching it with the routine endoscopic biopsy forceps, the “lasso” stitch at one of the edges, the proximal or the distal one. If the proximal one was grasped, stent was displaced without dragging mucosa, to peel stent off the mucosa and it was then pulled off completely. If the distal one was grasped, it was removed by invaginating the stent from within. If there was mucosal overgrowth, stent was lifted from it and removed [Figures 1 and 2].

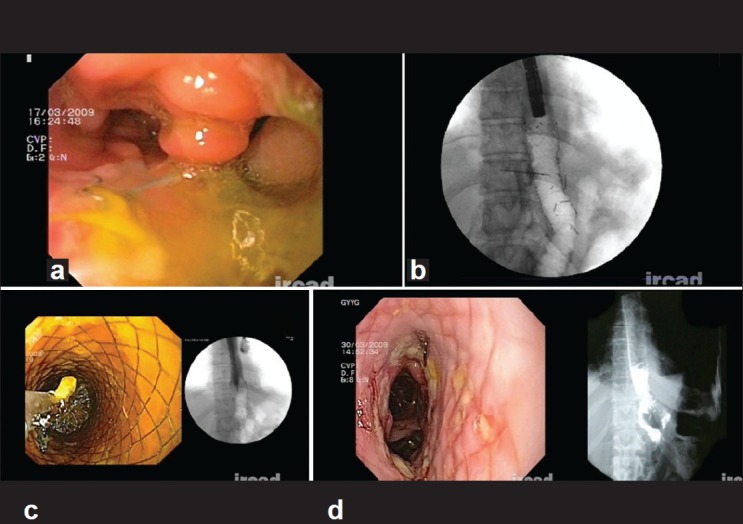

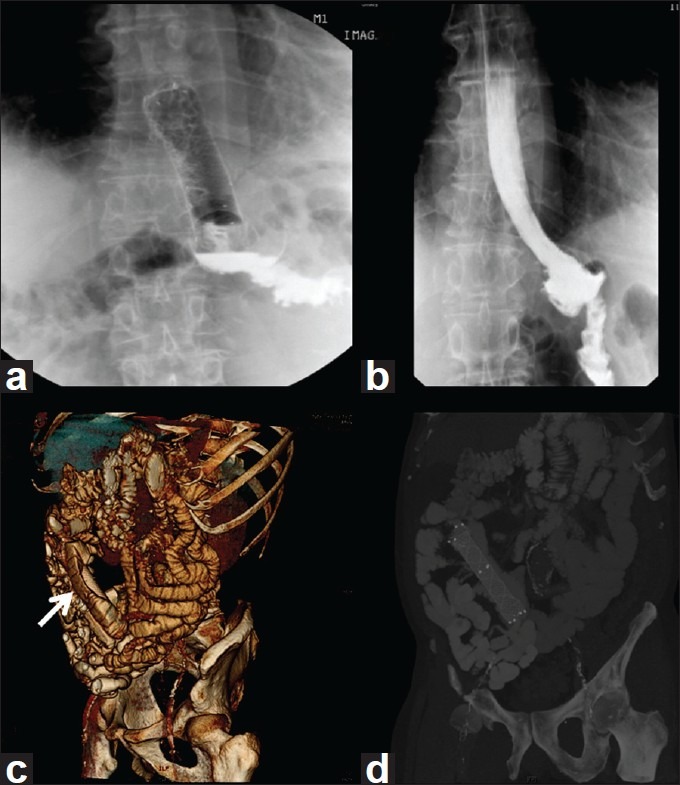

Figure 1.

Case of total gastrectomy: endoscopic picture of leak (a), stent in place (b), stent removal (c) and leak healed – endoscopic and radiologic picture (d)

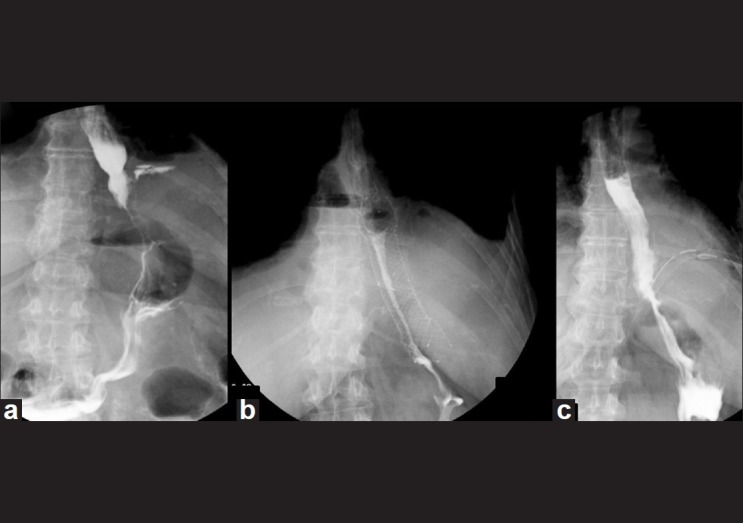

Figure 2.

Case of Collis Gastroplasty: Radiologic pictures showing leak (a), stent in place (b), and leak healed at stent removal (c)

RESULTS

Total 15 patients (6 male and 9 female) with an average age of 50.4 years (range =24-78 yrs) underwent endoscopic stenting for post-surgical foregut leaks. The primary laparoscopic surgeries were: 7 sleeve gastrectomies, 4 total gastrectomies, 2 Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses, and 1 each of Collis gastroplasty and distal esophagectomy. The average duration of presentation of the leak from the primary surgical intervention was 24.67 days (range=1-150 days). Patients’ demographic data and clinical data relevant to the leaks are detailed in Table 1.

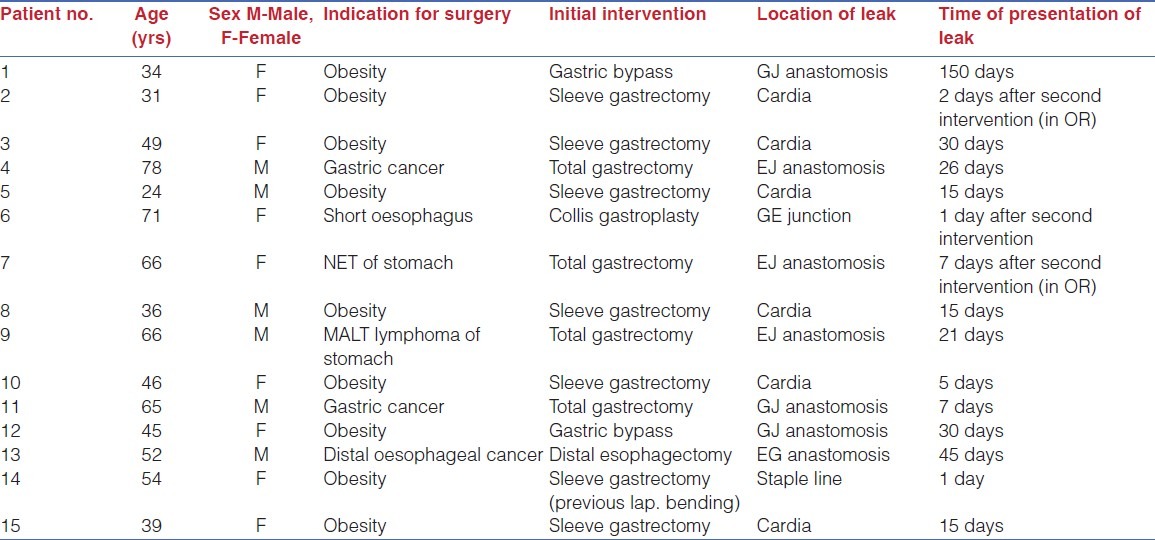

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the patients and description of leaks

Endoscopic placement of SEMS was successful in 14/15 patients (93%). Healing of the leak was achieved with 1 stent in 10 patients, 2 stents in 3 patients, with 1 patient each needing 3 and 4 stents. The stent had to be removed at day one in 1 patient for severe chest pain due to a stent twist. Further attempt to place the SEMS also failed due to up-migration. So, it was successfully managed by putting a naso-jejunal tube for feeding and monitoring. Our results are summarized in Table 2.

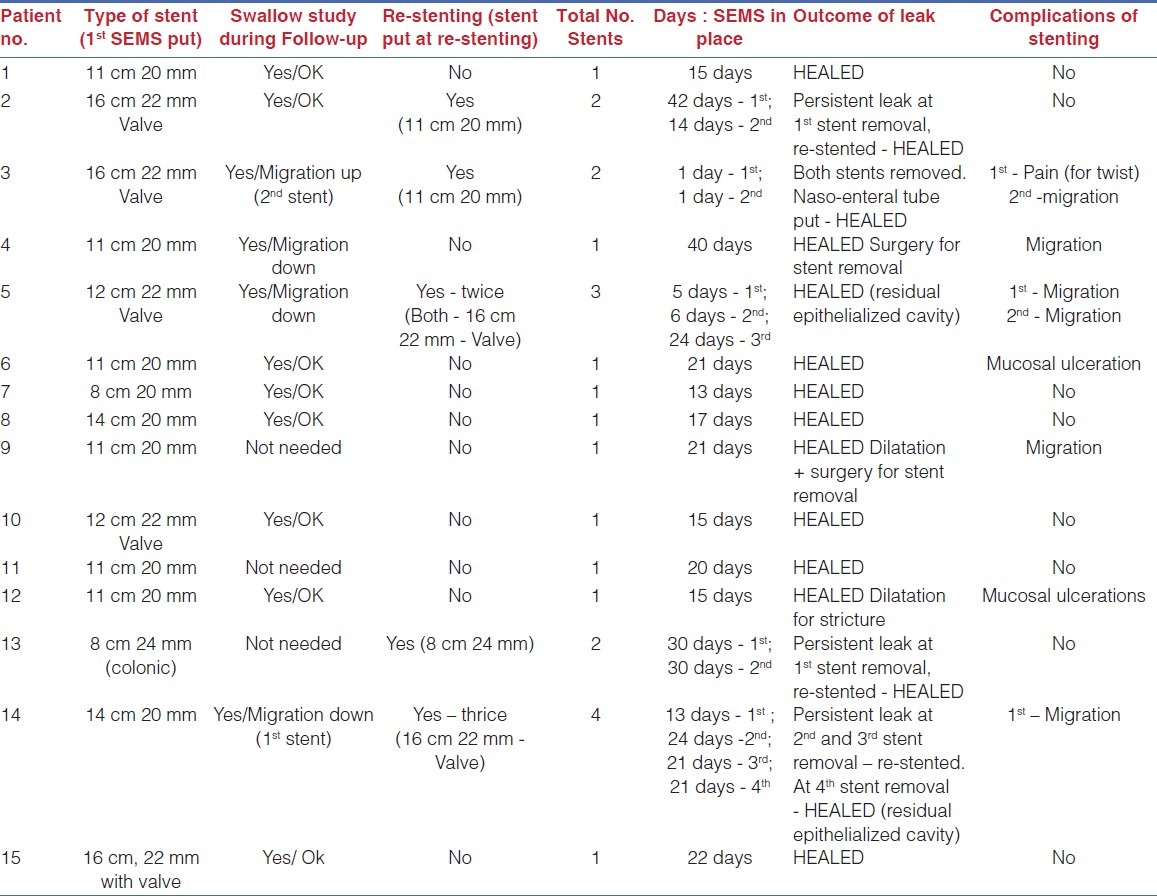

Table 2.

Results of SEMS placement

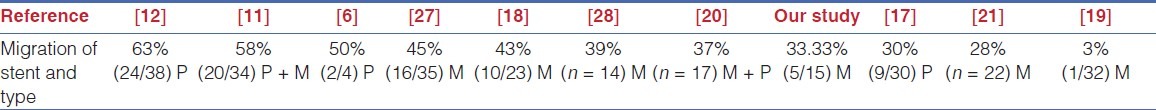

Stent migration was observed in 5/15 (33.33%) patients and in 7/23 (30.43%) stents inserted. Total 5/7 (71.42%) migrated stents could be retrieved by endoscopy. Two patients in whom the stent migrated to the small bowel had to be operated, 1 electively by laparoscopy, the second by open approach due to bowel obstruction [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Stent Migration: Stent in place for the leak (a), Leak well-healed, but stent is migrated (b), CT scan showing migrated stent in the small intestine (c) and 3D CT reconstruction showing migrated stent – white arrow head (d)

Three (20%) patients had a persistent leak at the time of removal of the initial stent and were re-stented. One of 3 had a persistent leak at the removal of second and third stent and was re-stented. Other 2 achieved complete healing of the leak. These 2 patients, both after sleeve gastrectomy, had a small residual re-epithelialized cavity at the time of last stent removal. Follow-up studies in 1 of these 2 patients showed complete obliteration of this cavity at the end of 3 months. Apart from migration, other complications observed in our series are mucosal ulceration at the distal end (2/15 patients, 13.33%) and pain (1/15 patients, 6.66%). The SEMS were in place for an average duration of 28.73 days (range=2-79 days) per patient and 18.73 days (range=1-42 days) per SEMS.

DISCUSSION

Important considerations in the management of foregut leaks include the nature of the presentation, the clinical and general condition of the patient, the aetiology and location of the leak, and assessment as to whether the leak is contained.[12]

The last decade has witnessed significant move from the historical aggressive surgical management to more conservative approaches. In a study of 63 patients with leaks after gastric bypass, mortality was 4/40 patients who required operative treatment as against 0/23 patients who were managed non-operatively.[13] In a recently published prospective study, Wedemeyer et al. achieved successful closure of the leaks using a novel technique of E-VAC (endoscopic vacuum assisted closure) in 7/8 patients with major intra-thoracic post-operative oesophageal leaks.[14]

Endoscopic stents were introduced in the early 1990s mainly for permanent treatment of tumour stenosis in cancer patients with an advanced disease.[15,16] Studies have demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of endoscopic placement of SEMS in patients with anastomotic leakage or perforation of the oesophagus who historically would have required surgical intervention.[8,17,18] Tuebergen et al. opined that earlier stenting might further decrease mortality and morbidity of post-operative leaks in the future.[8] Various studies have demonstrated healing rates for oesophageal/post-operative leaks in the range of 94%[19,20] - 32 %.[21] Even in long-standing perforations, those who would otherwise undergo oesophageal resection can still be good candidates for stent treatment.[22]

Endoscopic stenting for foregut post-operative leaks is a rather new therapeutic option and there are still number of issues regarding the ideal timing of placement, ideal stent, and duration of stenting to achieve healing and prevent the most frequent complications.

Johnsson et al. described a mortality rate of nearly 50% in patients when time of perforation to diagnosis and stent treatment was >24 hour compared to 0% if stent treatment occurred within 24 hours.[23] In the absence of any clear guidelines about timing and duration of stenting for benign oesophageal leaks, we preferred to stent immediately after (within 24 h) the diagnosis of leak is established, which is closely followed by improvement in clinical and biochemical parameters.

While fully covered SEMS is superior to plastic stent in terms of stent insertion-related mortality, morbidity and quality of palliation of malignant strictures.[24] Class I evidence to prove superiority of one type of stent over the other for benign oesophageal diseases is lacking. In a study of 38 patients with benign oesophageal diseases, placement of expandable plastic stents was less effective in the management of oesophageal leak or tracheo-oesophageal fistula, as compared to strictures, mainly because of high migration rates.[12] The main morbidity of covered stents is thought to be migration while that for uncovered stents was tissue in-growth and difficult extraction.[20] Covered metal stents can be removed safely in most patients with a low complication rate and are available with a larger diameter than silastic stents, allowing a water-tight bypass of the leak site.[25] In a small series of 6 patients using SEPS for anastomotic leaks arising from Roux-En-Y gastric bypass, Edwards et al. achieved a success rate of 84% at an average duration of 44 days with migration in 5/6 patients.[26]

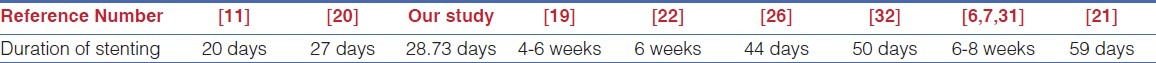

Migration is the most common complication reported in stenting of upper gastrointestinal (GI) pathologies [Table 3]. In the literature, the term migration includes true migration where the stents moved down totally to another segment of the GI tract, and dislodgement where the stent slips down or up and does not cover the leak anymore. In the present series, true migration was observed in 2/4 patients after total gastrectomy, and dislodgement in 3/7 patients after sleeve gastrectomy. In 2 of the latter patients, the leak was located at the cardia. This observation is in correlation with the literature that reports the oesophago-gastric junction as the most common site associated with migration.[17] Iqbal et al.[20] pointed out that the migration rate was significantly lower for nitinol stents, overlapping stents, polyester stents >15 cm, nitinol stents >12 cm. Many authors have suggested various solutions for reducing the rates of migration-like increasing the number of anti-migration struts,[27] deployment of 2 stents with a greater than 3 cm overlap,[18] a modification of the stent by leaving the upper flare uncoated and with 2 polypropylene (Prolene®) threads brought out and fixed to prevent migration.[29] Slightly stiffer, less compliant and longer stents have also been suggested for reducing migration.[20]

Table 3.

Migration rates (P = SEPS, M = SEMS)

Both HANAROSTENT® and plastic stents are covered, self-expandable and retrievable stents that are useful in the treatment of leakage. However, plastic stents require clips and silk sutures to secure the stent in place despite the presence of a proximal flare designed for improved stent fixation.[6] As compared with this, the HANAROSTENT® has 2 unique features for anti- migration. Larger bands at both ends of the stent almost fix it within the oesophagus. In addition, this unique segmented structure reduces the effect of outside pressure on the overall stent body while increasing the flexibility of the stent under peristaltic motion. We always try to place the stent of maximum size permissible to that of oesophagus to reduce the chances of migration.

There is again a lack of consensus for the duration a SEMS should remain inside the gut to achieve healing of the leak, avoid compression injuries and allow safe extraction. Animal studies suggest that 30 days should be adequate time for oesophageal healing.[30] Stent withdrawal is the only way to know if the fistula will persist or it is healed.[31] There exists a vast variation (20-59 days) in the duration SEMS has been kept inside the gut to achieve the healing. [Table 4] A study shows a 50% rate of complications like self-limiting bleeding, stent fracture and stent impaction in those cases in which stents were extracted ≥6 weeks after stent insertion.[22] In case of post-surgical leaks, with the surgical sutures holding the partially opened anastomosis or staple line, we believe that the SEMS should be left in place for a minimum possible duration, but at least for 2-3 weeks, because of the potential threat of SEMS putting some tension on the suture anastomosis, thus compromising the wound healing. In the only patient in whom the stent was removed at 42 days post-sleeve gastrectomy, we found a small patch of stomach wall ischemia, with an ulcer and persistent leak. We re-stented the patient for 14 days and then the ulceration was healed.

Table 4.

Duration of stent placement

The complication rate reported for SEMS is in the range of 23%[19]-29%.[20] Commonly reported complications are reflux,[18] pain, gastric ulcer, nausea and vomiting.[21,28] Self-healing ulcers (2 cm) have been reported in 50% of cases at the distal edge, whereas 23% at the proximal edge of the stent with pseudo-polyps and granulation tissue in some patients.[32] In a recently published retrospective analysis of 104 SEMS placed in 56 patients with mixed benign pathologies of oesophagus, long-term complications included stent-induced granulation tissue, most commonly at the distal end, seen at the time of stent removal of 12 stents (7 were obstructive, 5 were mild or non-obstructive). The authors further state that proximal stent placement is a risk factor for airway-related symptoms and may benefit from close clinical follow-up.[21] In our series, we had 2 cases of ulceration and just 1 case of moderate granulation tissue formation at the time of stent removal without any difficulty in stent retrieval. Stent extraction was shown not to be difficult if the stents were removed within a 30-day window except with occasional fracturing.[18] Eloubeidi and Lopes[32] reported the use of double-channel therapeutic upper endoscope with 2 rat-tooth forceps or a rat-tooth forceps and a snare as the preferred method for retrieval. Eighty two percent of stent retrievals were reported as very easy or easy. Bakken et al. reported in their retrospective analysis (n = 87) that all stents were removed with rat-toothed forceps without breakage or disintegration.[21] Our short experience is consistent with the data of the literature, as we did not encounter any problems during extraction even in the patient in whom stent was kept for 42 days.

CONCLUSION

Stenting with SEMS seems to be a feasible option as a primary care modality for patients with post-operative foregut leaks. Stenting may have some distinctive advantages of a minimally invasive therapy with satisfactory fistula healing rates and acceptable complication rates with about one-third of SEMS migrating. The stents should be removed within 4 weeks of placement and re-stenting is recommended if needed. Additional randomized, prospective studies are needed that can address this issue to fine-tune patient selection for stenting and minimize complications including migration.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schembre D. Advances in esophageal stenting: The evolution of fully covered stents for malignant and benign disease. Adv Ther. 2010;27:413–25. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brady R, Vroegop T, Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1290–8. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez R, Nelson LG, Gallagher SF, Murr MM. Anastomotic leaks after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1299–307. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall JS, Srivastava A, Gupta SK, Rossi TR, DeBord JR. Roux-en Y gastric bypass leak complications. Arch Surg. 2003;138:520–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.5.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters JH, Craanen ME, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA, Mulder CJ. Self-expanding metal stents for the treatment of intrathoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks following Esophagectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1393–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumoto R, Orlina J, McGinty J, Teixeira J. Use of polyflex stents in the treatment of acute esophageal and gastric leaks after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salinas A, Baptista A, Santiago E, Antor M, Salinas H. Self-expandable metal stents to treat gastric leaks. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:570–2. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuebergen D, Rijcken E, Mennigen R, Hopkins AM, Senninger N, Bruewer M. Treatment of thoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks and esophageal perforations with endoluminal stents: Efficacy and current limitations. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1168–76. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan JT, Kariyawasam S, Wijeratne T, Chandraratna HS. Diagnosis and management of gastric leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2010;20:403–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schubert D, Scheidbach H, Kuhn R, Wex C, Weiss G, Eder F, et al. Endoscopic treatment of thoracic esophageal anastomotic leaks by using silicone-covered, self-expanding polyester stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:891–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM, Ramaswamy A, de la Torre RA, Thaler KJ, et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:935–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennathur A, Chang AC, McGrath KM, Steiner G, Alvelo-Rivera M, Awais O, et al. Polyflex expandable stents in the treatment of esophageal disease: Initial experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1968–72. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez R, Sarr MG, Smith CD, Baghai M, Kendrick M, Szomstein S, et al. Diagnosis and contemporary management of anastomotic leaks after gastric bypass for obesity. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wedemeyer J, Brangewitz M, Kubicka S, Jackobs S, Winkler M, Neipp M, et al. Management of major postsurgical gastroesophageal intrathoracic leaks with an endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:382–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siersema PD. Treatment of esophageal perforations and anastomotic leaks: The endoscopist is stepping into the arena. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:897–900. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White RE, Mungatana C, Topazian M. Expandable stents for iatrogenic perforation of esophageal malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:715–20. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karbowski M, Schembre D, Kozarek R, Ayub K, Low D. Polyflex self-expanding, removable plastic stents: Assessment of treatment efficacy and safety in a variety of benign and malignant conditions of the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1326–33. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackmon SH, Santora R, Schwarz P, Barroso A, Dunkin BJ. Utility of removable esophageal covered self-expanding metal stents for leak and fistula management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:931–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leers JM, Vivaldi C, Schäfer H, Bludau M, Brabender J, Lurje G, et al. Endoscopic therapy for esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak with a self-expandable metallic stent. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2258–62. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iqbal A, Miedema B, Ramaswamy A, Fearing N, de la Torre R, Pak Y, et al. Long-term outcome after endoscopic stent therapy for complications after bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:515–20. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1203-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakken JC, Wong Kee Song LM, de Groen PC, Baron TH. Use of a fully covered self-expandable metal stent for the treatment of benign esophageal diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:712–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Heel NC, Haringsma J, Spaander MC, Bruno MJ, Kuipers EJ. Short-term esophageal stenting in the management of benign perforations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1515–20. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnsson E, Lundell L, Liedman B. Sealing of esophageal perforation or ruptures with expandable metallic stents: A prospective controlled study on treatment efficacy and limitations. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:262–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yakoub D, Fahmy R, Athanasiou T, Alijani A, Rao C, Darzi A, et al. Evidence-based choice of esophageal stent for the palliative management of malignant dysphagia. World J Surg. 2008;32:1996–2009. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer FB, Wenzl E, Prager G, Salat A, Miholic J, Mang T, et al. Management of postoperative esophageal leaks with the Polyflex self-expanding covered plastic stent. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards CA, Bui TP, Astudillo JA, de la Torre RA, Miedema BW, Ramaswamy A, et al. Management of anastomotic leaks after Roux-en-Y bypass using self-expanding polyester stents. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:594–9. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uitdehaag MJ, van Hooft JE, Verschuur EM, Repici A, Steyerberg EW, Fockens P, et al. A fully-covered stent (Alimaxx-E) for the palliation of malignant dysphagia: A prospective follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1082–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senousy BE, Gupte AR, Draganov PV, Forsmark CE, Wagh MS. Fully covered alimaxx esophageal metal stents in the endoscopic treatment of benign esophageal diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3399–403. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1415-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mejía AF, Bolaños E, Chaux CF, Unigarro I. Endoscopic treatment of gastrocutaneous fistula following gastric bypass for obesity. Obes Surg. 2007;17:544–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takimoto Y, Nakamura T, Yamamoto Y, Kiyotani T, Teramachi M, Shimizu Y. The experimental replacement of a cervical esophageal segment with an artificial prosthesis with the use of collagen matrix and a silicone stent. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:98–106. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casella G, Soricelli E, Rizzello M, Trentino P, Fiocca F, Fantini A, et al. Nonsurgical treatment of staple line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2009;19:821–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eloubeidi MA, Lopes TL. Novel removable internally fully covered self-expanding metal esophageal stent: Feasibility, technique of removal, and tissue response in humans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1374–81. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]