Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the wound-healing potency of the ethanolic extract of the flowers of Hibiscus rosa sinensis.

Materials and Methods:

The wound-healing activity of H. rosa sinensis (5 and 10% w/w) on Wistar albino rats was studied using three different models viz., excision, incision and dead space wound. The parameters studied were breaking strength in incision model, granulation tissue dry weight, breaking strength and collagen content in dead space wound model, percentage of wound contraction and period of epithelization in excision wound model. The granulation tissue formed on days 4, 8, 12, and 16 (post-wound) was used to estimate total collagen, hexosamine, protein, DNA and uronic acid. Data were analyzed by Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The extract increased cellular proliferation and collagen synthesis at the wound site, as evidenced by increase in DNA, total protein and total collagen content of granulation tissues. The extract-treated wounds were found to heal much faster as indicated by improved rates of epithelialization and wound contraction. The extract of H. rosa sinensis significantly (P<0.001) increased the wound-breaking strength in the incision wound model compared to controls. The extract-treated wounds were found to epithelialize faster, and the rate of wound contraction was significantly (P<0.001) increased as compared to control wounds. Wet and dry granulation tissue weights in a dead space wound model increased significantly (P<0.001). There was a significant increase in wound closure rate, tensile strength, dry granuloma weight, wet granuloma weight and decrease in epithelization period in H. rosa sinensis-treated group as compared to control and standard drug-treated groups.

Conclusion:

The ethanolic extract of H. rosa sinensis had greater wound-healing activity than the nitrofurazone ointment.

KEY WORDS: Collagen, granulation tissue, granuloma tissue, Hibiscus rosa sinensis, tensile strength

Introduction

Hibiscus rosa sinensis Linn. (Malvaceae) is a glabrous shrub widely cultivated in the tropics as an ornamental plant. Its 250 species are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions and are reported to posses various medicinal properties including antitumor, antihypertensive, antioxidant and antiammonemic.[1–4] The leaves and flowers are observed to be promoters of hair growth and aid in healing of ulcers,[5,6] flowers have been found to be effective in the treatment of arterial hypertension[7] and have significant antifertility effect.[8,9]

Wound healing is the process of repair that follows injury to the skin and other soft tissues. Following injury, an inflammatory response occurs and the cells below the dermis begin to increase collagen production. Later, the epithelial tissue (the outer skin layer) is regenerated. There are three stages in the process of wound healing : i0 nflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. The proliferative phase is characterized by angiogenesis, collagen deposition, epithelialization and wound contraction. Angiogenesis involves new blood vessel growth from endothelial cells. In fibroplasia and granulation tissue formation, fibroblasts exert collagen and fibronectin to form a new, provisional extracellular matrix. Subsequently, epithelial cells crawl across the wound bed to cover it and the wound is contracted by myofibroblasts, which grip the wound edges and undergo contraction using a mechanism similar to that in smooth muscle cells. Hence, the present study was taken up to investigate the efficacy of topical application of H. rosa sinensis by phytochemical, biochemical and histological methods in the process of wound healing.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Preparation of Extract

H. rosa sinensis flowers were collected from Tiruchirappalli district, Tamil Nadu, India. The plant was authenticated by Dr. S. Kalavathy, Associate Professor, Department of Botany, Bishop Heber College, Trichy, and molecular taxonomy of the plant was done by sequencing the 18SrDNA of the plant. H. rosa sinensis L., flowers were shade-dried at room temperature, pulverized by a mechanical grinder, sieved through 40-size sieve mesh. 500 g of fine flower powder was suspended in 1500 ml of ethanol for 24 h at room temperature. The mixture was filtered using a fine muslin cloth followed by filter paper (Whatmann No: 1). The filtrate was placed in a water bath to dry at 40°C and the final ethanol-free clear residue was used for the study.

Ointment Formulation

Two types of ointment formulations were prepared from the extract: 5% to 10% (w/w), where 5 or 10 g of the extract was incorporated into 100 g of simple ointment base British Pharmacopoeia (B.P) respectively. Nitrofurazone ointment (0.2% w/w, Smith Kline-Beecham Pharmaceuticals Bangalore, India) was used as a standard drug for comparing the wound- healing potential of the extract.

Qualitative Phytochemical Evaluation

The flower extract was subjected to qualitative tests by adopting standard procedure for the identification of the phytoconstituents present in it viz., alkaloids, carbohydrates, glycosides, phytosterols, fixed oils, phenolic compounds, proteins, free amino acids, gums, mucilage, flavonoids, terpenoids, lignins, and saponins.[10]

Animals

Wistar albino rats (150-250 g body weight) were used after an acclimatization period of 7 days to the laboratory environment. They were provided with food and water ad libitum. The work was carried out in CPCSEA approved (743/03/abc/CPCSEA dt. 3.3.03) Animal House of PRIST University, Thanjavur.

Excision Wound

The rats were inflicted with excision wounds as described by Morton and Malone[11] under light ether anesthesia. One excision wound was made by cutting away a 500 mm2 full thickness of skin from the depilated area, the wound was left undressed to open environment. The animals were divided into four groups of six each. The animals of group I were left untreated and considered as the control, group II served as reference standard and treated with 0.2% w/w nitrofurazone ointment, animals of group III and IV were treated with 50 mg of ointment prepared from 5% to 10% (w/w) of ethanolic extract of H. rosa sinensis. The ointment was topically applied once a day, starting from the day of the operation, till complete epithelization. This model was used to monitor wound contraction and wound closure time. Wound contraction was calculated as percentage reduction in wound area. The progressive changes in wound area were monitored planimetrically by tracing the wound margin on graph paper every alternate day. The period of epithelialization was calculated as the number of days required for falling of the dead tissue remnants of the wound without any residual raw wound.

Incision Wounds

In incision wound model, 6 cm long paravertebral incisions were made through the full thickness of the skin on either side of the vertebral column of the rats as described by Ehrlich and Hunt et al.[12] The wounds were closed with interrupted sutures, 1 cm apart. The animals of group I were left untreated (control), the group II served as reference standard and received 0.2% w/w nitrofurazone ointment, animals in groups III and IV were treated with ointment prepared from 5% to 10% w/w ethanolic extract of H. rosa sinensis flower extract. The ointment was topically applied once a day. The sutures were removed on the 7th day. Wound-breaking strength was measured in anesthetized rats on the 10th day after wounding.

Dead Space Wound

The animals were divided into three groups of 6 rats in each group. Group I served as the control, which received 2 ml of 1% carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) orally. The animals of group II and III received oral suspension of H. rosa sinensis (5% w/w and 10% w/w) for 10 days. Under light ether anesthesia, dead space wounds were created by subcutaneous implantation of sterilized cylindrical grass liths (2.5×0.3 cm), one on ether side of the dorsal paravertebral surface of the rats.[13] On the 11th post-operative day, the dead space wound was excised. Wet weight was recorded and tensile strength determined.[14] The granuloma was dried in an oven at 60°C and the dry weight noted. The tensile strength was measured using a tensiometer.

Measurement of Healing

Tensile strength, the force required to open a healing skin wound, was used to measure healing. The instrument used for this measurement is tensiometer. It was designed on the same principle as the thread tester used in the textile industry. It consisted of a 6×12 inch board with one post of 4 inch long, fixed on each side of the longer ends. The board was placed at the end of a table. A pulley with a bearing was mounted on the top of one of the posts. An alligator clamp with 1 cm width, was tied on the tip of the post without pulley by a piece of fishing line (20-lb test monofilament) so that the clamp could reach the middle of the board. Another alligator clamp was tied on a piece of fishing line with a 1 L polyethylene bottle tied on the other end. The excised granuloma tissue was then placed on a stack of paper towels that could be adjusted so that the polyethylene bottle was freely hanging in the air. Water added to the polyethylene bottle was weighed and considered as the tensile strength of the wound.

Collection of Granulation Tissue from Dead Space Wound

Granulation tissues from control and test groups were collected and washed in cold saline (0.9% NaCl) to remove the blood tissues and stored for various parameters. The granulation tissues were lyophilized for collagen and hexosamine analysis.

Biochemical Estimations

Protein and DNA of wet granulation tissues were extracted in 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) as per Porat et al.[15] 10 ml of 5% TCA was added to the tissue (100 mg wet wt. of tissue) kept at 90°C for 30 min in a water bath to extract protein and DNA. The solution was then centrifuged and the supernatant was used to estimate DNA by the method of Burton[16] and protein by the method of Lowry et al.[17] To estimate collagen and hexosamine, the tissue samples were defatted in chloroform :0 methanol (2:1) and dried in acetone before use. Collagen was estimated by the method of Woessner,[18] whereas hexosamine and uronic acid were estimated by the method of and Elson and Morgon[19] and Schiller et al.,[20] respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM and subjected to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test for comparison.

Result

In the preliminary phytochemical evaluations of the ethanolic extract of H. rosa sinensis Linn. Flower powder showed the presence of alkaloids, phytosterol, phenolic compounds and tannins, flavonoids and saponins.

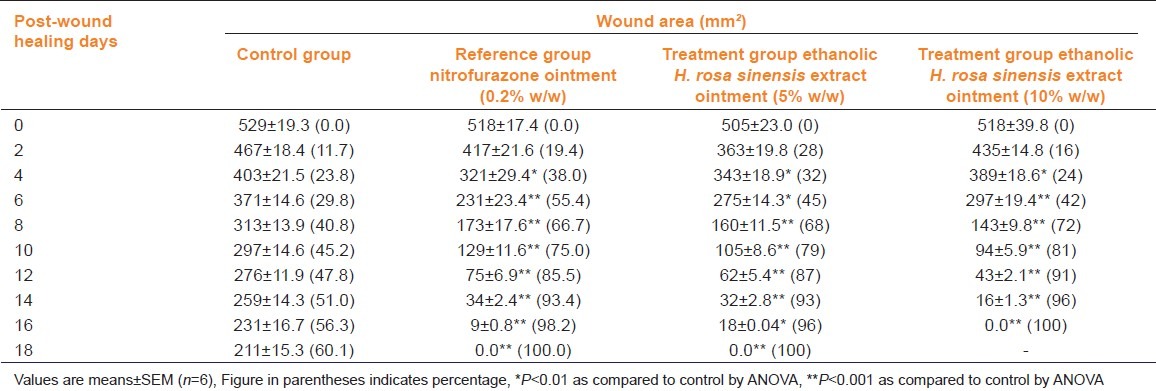

Wound-healing activity was observed in all three models viz. excision, incision, and dead space wound. Table 1 shows the wound contracting ability of the extract ointment was significantly greater (P <0.01) than control as well as reference standard (NFZ ointment). The extract ointment produced complete healing at 18th day and 16th day with 5 and 10% w/w extract ointment respectively.

Table 1.

Effect of Hibiscus rosa sinensis extract ointment on excision model in rats

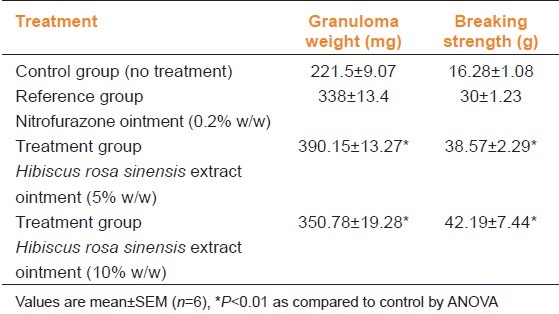

In the incision wound model, a significant increase (P<0.01) in breaking strength (g) was observed in rats treated with 5 and 10% H. rosa sinensis extract ointment, respectively when compared to controls treated with NFZ ointment [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of effect of Hibiscus rosa sinensis extract ointment on incision wound in rats

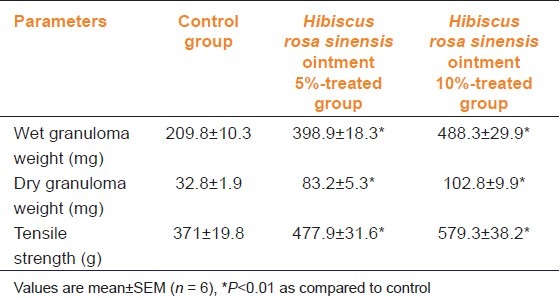

Table 3 shows the effect of H. rosa sinensis ointment on the dead space wound. Compared to the control group of animals, 10% extract-treated animals showed significant increase in dry weight of granulation tissue, wet weight granulation tissue and breaking strength.

Table 3.

Comparison of effect of Hibiscus rosa sinensis extract ointment on dead space wound in rats

The biochemical estimation of collagen, hexosamine, DNA, protein and uronic acid were carried out on 4, 8, 12 and 16 days of treatment [Table 4]. The DNA content showed a three-fold increase within the 8th day and a maximum on the 12th day, proteins also showed a similar increase suggesting that tissue repair increased with treatment using the plant extract. Uronic acid, hexosamine and total collagen were also found to be significantly (P<0.001) increased with treatment when compared to the controls.

Table 4.

Comparison of effect of Hibiscus rosa sinensis extract ointment on various biochemical parameters in rats

Discussion

Wound healing is the process of repair following injury to the skin and other soft tissues. It is a complex and dynamic process of restoring cellular structures and tissue layers in damaged tissue as closely as possible to its normal and original state.[21] Topical application of H. rosa sinensis improved wound contraction and closure and the effects were distinctly visible starting from 4th post-wounding day.

The preliminary phytochemical investigation of the flower extract showed the presence of flavonoids, saponins, terpenoids and tannins. Studies have shown that flavonoids promote the wound-healing process mainly due to their astringent and antimicrobial properties which appear to be responsible for the wound healing.[10] The wound-healing property of H. rosa sinensis flower extract may be attributed to its high flavonoid content. Flavonoids and terpenoids are found to promote the wound- healing process mainly due to their antimicrobial property. These phytoconstituents present in the plant drug under study may be responsible for wound contraction and increased rate of epithelialization observed in the present work.

The wound-breaking strength is determined by the rate of collagen synthesis and more so by the maturation process where there is covalent binding of collagen fibrils through inter- and intra-molecular cross-linking.[22] In the present study, a significant increase in tensile strength on the 12th day was observed in the test group as compared to the control group. Collagen is a major protein of the extracellular matrix and is the component that ultimately contributes to wound strength.[14] The healing process depends, to a large extent, on the regulated biosynthesis and deposition of new collagens and their subsequent maturation.[23] Assessment of collagen content in granulation tissues of control and experimental wounds clearly suggests that H. rosa sinensis enhances collagen synthesis and deposition. The amount of collagen may be increased in total cell number as a result of increased cell division.

Hexosamine and uronic acid are matrix molecules, which act as ground substrate for the synthesis of new extracellular matrix. It is reported that there is an increase in the levels of these components during the early stages of wound healing, following which normal levels are restored.[24] The increase in DNA content in the treated wounds indicates cellular hyperplasia. A similar trend was observed in H. rosa sinensis treated wounds wherein the levels of hexosamine and uronic acid increased up to day 8 post-wounding and decreased thereafter.

It can be concluded from the present findings that H. rosa sinensis flower extract could be efficiently used as a wound-healing agent. Wound contraction, increased tensile strength activity support further evaluation of H. rosa sinensis in the topical treatment and management of wounds.

Footnotes

Source(s) of Support: Nil.

Conflicting Interest: No.

References

- 1.Hou DX, Tong X, Terahara N, Luo D, Fujii M. Delphinidin 3-sambubioside, a Hibiscus anthocyanin, induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells through reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;440:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirunpanich V, Utaipat A, Morales NP, Bunyapraphatsara N, Sato H, Herunsale A, et al. Hypocholesterolemic and antioxidant effects of aqueous extracts from the dried calyx of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in hypercholesterolemic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:252–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang YC, Huang KX, Huang AC, Ho YC, Wang CJ. Hibiscus anthocyanins-rich extract inhibited LDL oxidation and oxLDL-mediated macrophages apoptosis. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:1015–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrera-Arellano A, Flores-Romero S, Chávez-Soto MA, Tortoriello J. Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: A controlled and randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali M, Ansari SH. Hair care and herbal drugs. Indian J Nat Prod. 1997;13:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurup PN, Ramdas VN, Joshi P. Handbook of Medicinal Plants. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd; 1979. pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kate IE, Lucky OO. The effect of aqueous extracts of the leaves of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis Linn. On renal function in hypertensive rats. African J Biochem Res. 2010;4:43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh MP, Singh RH, Udupa KN. Antifertility activity of a benzene extract of Hibiscus rosa sinensis flowers on female albino rats. Planta Medica. 1982;44:171–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi N, Nath D, Singh RK. Teratological study of an indigenous antifertility medicine, Hibiscus rosa sinensis in rats. Arogya J Health Sci. 1986;12:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuchiya H, Sato M, Miyazaki T, Fujiwara S, Tanigaki S, Ohyama M, et al. Comparative study on the antibacterial activity of phytochemical flavanones against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50:27–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(96)85514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morton JJ, Malone MH. Evaluation of vulneray activity by an open wound procedure in rats. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1972;196:117–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrlich HP, Hunt TK. Effects of cortisone and vitamin A on wound healing. Ann Surg. 1968;167:324–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196803000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner RA. Anabolic, androgenic and antiandrogenic agents. In: Turner RA, editor. Screening Methods in Pharmacology. Chapter 33. New York and London: Academic Press; 1965. pp. 244–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan SW, Abubakar MG, Umar RA, Yakubu AS, Maishanu HM, Ayeni G. Pharmacological and toxicological properties of leaf extracts of Kingelia africana (bignoniaceae) J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;6:124–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porat S, Roussa M, Shosan S. Improvement of the gliding functions of flexor tendons by topically applied enriched collagen solution. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62:208. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.62B2.6245095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton K. A study of the conditions and mechanism of the diphenylamine reaction for the colorimetric estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J. 1956;62:315–23. doi: 10.1042/bj0620315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RT. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woessner JF., Jr The determination of hydroxy proline in tissue and protein samples containing small proportions of this imino acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;93:440–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elson LA, Morgan WT. Water electrolyte and nitrogen content of human skin. Proc soc Exp Biol. 1993;58:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiller S, Slover G, Dorfman AA. A new perspective with particular reference to ascorbic acid deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1961;36:983–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark RA. Cutaneous tissue repair. I Basic biologic consideration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:701–25. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanbhag TV, Sharma C, Sachidananda A, Kurady BL, Smita S, Ganesh S. Wound healing activity of alcoholic extract of Kaempferia galangal in wistar rats. Ind J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;50:384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puratchildy A, Nithya C, Nagalakshmi G. Wound healing activity of Cyperus rotundus Linn. Ind J Pharmaceutical Sci. 2006;68:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R, Katoch SS, Sharma S. β-Adrenoreceptor agaonist treatment reverses denervation atrophy with augmentation of collagen proliferation in denervated mice gastrocnemius muscle. Ind J Exp Biol. 2006;44:371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]