Abstract

Aim:

In 2009, a flu pandemic caused panic worldwide. Oseltamivir and zanamivir were widely used in this pandemic. Currently, there are a limited number of studies comparing the efficacy and tolerability of these two drugs. This study aimed to compare the efficacy and tolerability of these two drugs in the treatment of influenza.

Materials and Methods:

Patients diagnosed with influenza at our infectious disease outpatient clinic during the influenza season between October 1, 2009 and February 1, 2010 were included in the study. Study data were obtained retrospectively from files for consecutive patients. A total of 136 subjects were selected. After exclusion criteria were applied, 56 subjects were discarded. The information for 80 patients in whom oseltamivir or zanamivir therapy was initiated (40 for each therapy) was compiled, and the efficacy and tolerability of the drugs were compared.

Results:

There was no significant difference in efficacy for the two drugs (P > 0.05). Temperature normalization was significantly faster in patients taking zanamivir (P = 0.0157). Drowsiness was the most frequent adverse event for both drugs (38% for the oseltamivir group, and 22% for the zanamivir group). Respiratory distress was observed in five patients in the zanamivir group, whereas it was not observed in patients in the oseltamivir group (P < 0.05). One patient had to discontinue therapy in the zanamivir group due to respiratory distress.

Conclusion:

Efficacy (in terms of symptom relief and duration to resumption of work) and adverse events were similar for zanamivir and oseltamivir, but temperature normalization was much more rapid in patients using zanamivir. Patients using zanamivir should be monitored for respiratory distress.

KEY WORDS: Influenza, oseltamivir, pandemic, zanamivir

Introduction

Influenza virus is a segmented-genome, negative-polarity, enveloped RNA virus. Minor or major alterations in the genomic structure of the influenza virus (called drift in the case of minor alterations, and shift with major alterations) can cause global pandemics.[1,2] The virus caused major pandemics in 1918 (H1N1), 1957 (H2N2), and 1968 (H3N2), and led to the death of many people.[3] More recently, in February 2009, a pandemic that affected the entire world started in Mexico; during this pandemic, there were more than 340 000 laboratory-confirmed cases, with more than 11160 deaths reported.[4,5] On review of the epidemiological data, it was calculated that the symptoms for the pandemic H1N1 infections persisted on average for about 7 days. The hospitalization rate was 4.5% (range: 3.8-5.2%), the clinical attack rate was 29%, and the fatality rate was 0.4% (range: 0.3 to 1.8%).[6–9]

Amantadine and rimantadine inhibit the viral M2 protein and have been used for treating flu, but resistance was reported to both of these compounds during the last influenza outbreak.[5,9,10] Neuraminidase inhibitors are the drugs that prevent release of the virus. During the last outbreak, the two neuraminidase inhibitors, oseltamivir, and zanamivir, were used in the treatment of the H1N1 pandemic in many countries. It was reported that oseltamivir and zanamivir could reduce the severity and duration of the disease, and prevent deaths.[11] Oseltamivir is used orally (2 × 75 mg) in treatment of influenza whereas zanamivir is taken via an oral inhaler (2 × 5 mg).[12]

Although different adverse events for both drugs were reported in some countries, there are a limited number of studies that compared the efficacy and adverse events of oseltamivir and zanamivir for the treatment of influenza. This retrospective study aimed to compare the efficacy and tolerability of both drugs.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was conducted by including patients who retrospectively met the study criteria. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee. Patient records were obtained from consecutive patient files for individuals who presented to Sakarya Education and Research Hospital between October 2009 and February 2010 during the pandemic period and were diagnosed with flu. The diagnosis was confirmed both clinically and via laboratory tests. A total of 136 patient records were obtained, but 56 of these were discarded [Figure 1]. Of the 80 remaining patients, 40 had been treated with oseltamivir, and 40 with zanamivir. Patients who fulfilled the following criteria were included:

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study

Fever ≥38°C and the presence of at least one of the following symptoms: sore throat, headache, myalgia, weakness, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, cough, rhinorrhea, and respiratory distress.

-

Initiated on either oseltamivir or zanamivir within the first 48h of disease onset.

Not receiving other drugs for palliation of symptoms (e.g., anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-pyretic drugs, and cough syrup).

Who were diagnosed to be suffering from influenza, and who were in the age group of 17-70 years.

Not requiring hospitalization.

Body mass index <30.

Non- pregnant females.

Not with chronic diseases such as bronchial asthma.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who tested negative for influenza infection on polymerase chain reaction assay testing (PCR testing) were excluded from the study. Patients with chronic diseases like bronchial asthma were also excluded.

Treatment

Zanamivir was administered to adults twice a day as a 10 mg (2 × 5 mg) oral inhaler for 5 days. Oseltamivir was administered to adults twice a day as 150 mg (2 × 75 mg) PO for 5 days.

Tests

The time taken for axillary temperature to be normal, decrease in myalgia, loss of symptoms, and lack of complications were considered as healing criteria. The patients in the outpatient clinic and diagnosed with influenza were screened. It was checked if PCR test was done from a nasal swab for H1N1 when they first consulted in the clinic. Due to the excessive number of patients during the pandemic, every patient could not be given an H1N1 PCR test. Only eight patients (10%) received an H1N1 PCR test. ALT, AST, CBC, CRP, urea, creatinine, blood glucose, and creatinine kinase levels were measured on the day the patient first consulted, on the second day of treatment and at the end of treatment (5th day) during the pandemic period. Taking these values into consideration, all adverse events were recorded. Influenza PCR tests were sent to be studied at the Turkey Ministry of Health Ankara Hıfzıssıhha Institute.

Clinical Evaluation

In order to evaluate adverse events, tests carried out on the patients were reviewed. Registered file information helped to determine whether the patients who were called for check-up on the 2nd and 5th days developed adverse events during this period. The adverse events reviewed in patient files were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, drowsiness, psychiatric problems, confusion, respiratory distress, rash, and skin eruption. The adverse events developing after drug ingestion alone were attributed to the drug.

Follow-up treatment was done on the 2nd and 5th day of illness. Patients were phoned in order to learn when the fever had subsided, the symptoms disappeared, myalgia decreased, and how many days later could they start working, and whether any complication had developed, during the illness. History of any other drugs (anti-inflammatory drugs, antitussives, or antipyretics) taken by the patients were also taken. We investigated patient records for temperature readings. Fever defervescence was defined as the interval from the initiation of oseltamivir or zanamavir until return to normal body temperature for more than 24h.

Statistical Evaluation

Epi-Info Ver 6.0 (CDC Atlanta, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For quantifiable variables, Student's t-test was used, and for categorical variables, X2 test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographical Properties

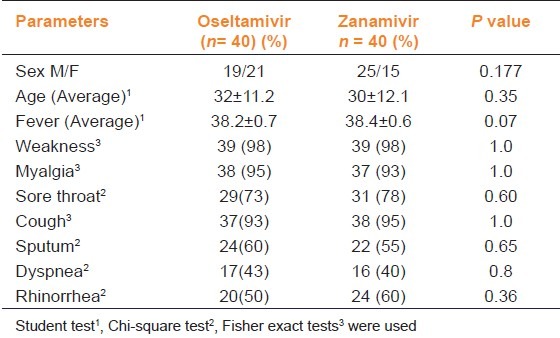

A total of 80 patients were included in the study during the influenza period, 44 of whom were males and 36 were females (M/F ratio was 1.22). The average age of the patients was 30.8 ± 11.6 (min: 17, avg: 28, max: 65). Among these patients, weakness was detected in 97.5%, myalgia in 93.8%, nausea in 46.3%, and diarrhea in 23.8%. The demographic data of the patients were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients prescribed oseltamivir or zanamivir in pandemic influenza

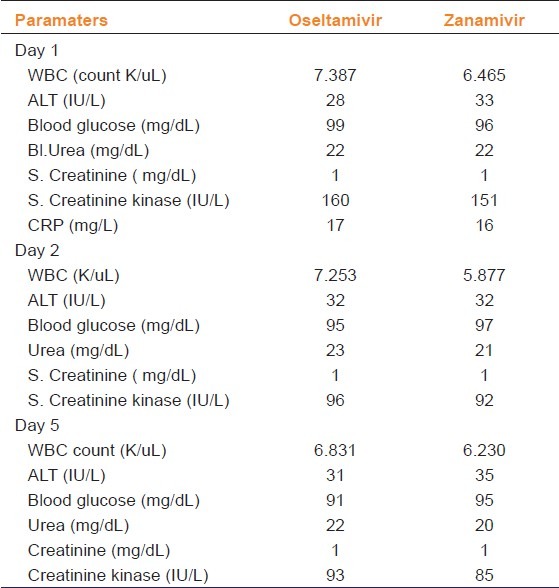

Laboratory Values

The average baseline WBC value was 7.3 K/uL in the oseltamivir group as opposed to 6.4 K/uL in the zanamivir group. The average urea value was 22 mg/dl in both the groups. On reassessing the laboratory parameters on Day 2 and 5 of treatment, no significant difference was observed between the groups. The laboratory parameters measured during treatment were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory values of the patients in pandemic influenza according to drugs prescribed

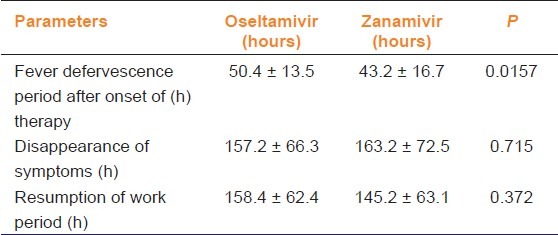

Efficiency Values of Oseltamivir and Zanamivir

The temperature was monitored after treatment was initiated. While the defervescence period was 50.4h in the oseltamivir group, it was 43.2h in the patient group receiving zanamivir (P = 0.0157). The period until disappearance of other symptoms was a mean of 157.2 h for oseltamivir, whereas it was 163.2 h in zanamivir group (P > 0.05). While the duration until resuming work was 158.4 h for oseltamivir, it was 145.2 h for zanamivir (P > 0.05). No life-threatening complications were observed in either group (P > 0.05). Efficiency values are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of efficacy of oseltamivir and zanamivir in pandemic influenza

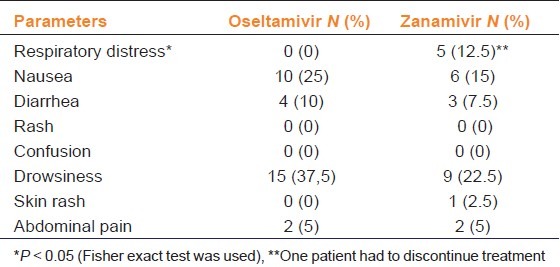

Adverse Effects of Oseltamivir and Zanamivir

The most frequent adverse event in patients who were initiated on oseltamivir and zanamvir was drowsiness, 37.5 and 27.5%, respectively. The second most frequent event was nausea. Nausea was detected as an adverse event in ten cases (25%) in the oseltamivir group and in six cases (15%) in the zanamivir group.

We observed no serious adverse events. No patient died due to adverse events. No drug discontinuation was required due to adverse events, except for one patient in the zanamavir group. Respiratory distress was not observed in patients using oseltamivir. One of the patients who was initiated on zanamivir discontinued therapy due to the onset of respiratory distress, while development of respiratory distress was observed in five (12.5%) patients using Zanamivir, (P < 0.05). Adverse effects of oseltamivir and zanamivir are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of drug related adverse events in patients suffering from influenza

Discussion

Influenza is a virus that infects and may kill many people throughout the world. For years, amantadine and rimantadine have been used in the treatment of influenza. H1N1 virus is considered to be resistant to M2 inhibitors (amantadine and rimantadine) while it is sensitive to neuraminidase inhibitors (oseltamivir and zanamivir).[8–10] During H5N1 (2005) and H1N1 (2009) outbreaks neither amantadine nor rimantadine could be used due to resistance. In the 2009 pandemic, resistance to oseltamivir was reported to be 0.5%, whereas no resistance was reported to zanamivir.[13]

It was reported that when drugs were started within the first 48 h of the disease, neuraminidase inhibitors not only reduced the infectivity, but also reduced the duration of symptoms and mortality.[14] In 2009 flu outbreak, only these two drugs could be used. However, to the best of our knowledge there is not sufficient data comparing the efficacy of these two drugs. In the present study, the efficacy and tolerability of these two drugs were compared with a retrospective study. In our research, in the 40 patients who used oseltamivir and 40 patients who used zanamivir no significant difference was seen between the two drugs in terms of duration of disappearance of symptoms, duration for resuming work, or development of complications. However, it was detected that fever resolved more rapidly in those using zanamivir (43.2h) compared to those using oseltamivir (50.4 h) (P < 0.05). Normalization of fever is important to patients with flu for better health quality as the patients can return to work more quickly. It has also been observed in other studies that defervescence occurs earlier in patients on zanamivir.[15]

On comparison of the adverse events of both drugs, the most frequent adverse event was drowsiness. The drowsiness rate observed was 37.5 and 22.5% for oseltamivir and zanamivir groups, respectively (P > 0.05). In a study with 294 patients, sedation was seen for only 5% of the patients.[16] It is appropriate high rate may be related to the fact that during a pandemic, people are in a state of anxiety that may trigger drowsiness.

Other adverse events included nausea, in the oseltamivir group 25% and in the zanamivir group 15%. Some cases were reported with events such as neuropsychiatric changes, delirium, hallucination, changes in behavior, and suicide.[17] However, in patients within the study group, psychiatric problems were observed in 7.5% of those who received oseltamivir and 5% of those who received zanamivir.

While respiratory distress was not observed in those who used oseltamivir, it was seen in 12.5% of the zanamivir group (P < 0.05). Moreover, one patient's treatment had to be discontinued due to this adverse event. This situation was considered to be associated with the bronchial constriction by zanamivir. Zanamivir has a low bioavailability (2%). However, it can be concentrated in the oropharynx, respiratory airways, and lungs after inhalation.[13] Similar reports concerning zanamivir have been reported. For instance, in a 2000 patient study, it was reported that 17 patients (0.85%) had bronchial spasm and that those with respiratory problems should use the drug with care.[18] In another report, bronchial constriction requiring hospitalization was reported following the use of zanamivir in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[19] Based on these results, it was considered that zanamivir should be used with caution in those with underlying respiratory tract diseases.

However, we should mention some limitations of our study. This was a retrospective study, which relied on data on file. Another significant limitation was that only 80 patients could be included in the study. The number of files which met the criteria required in the study was considerably less. However, in spite of these limitations, we believe this study is valuable due to a lack of similar data in literature.

Conclusion

Zanamivir and oseltamivir were found to have similar efficacy in terms of symptom relief and duration to resumption of work during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. However, temperature normalization was more rapid in patients using zanamivir. Neither drug was observed to have serious adverse events. However, it was concluded that those who used zanamivir suffered from respiratory distress more often, and therefore care should be taken with those taking zanamivir, for possible development of this adverse effect.

Footnotes

Source(s) of Support: Sakarya University BAP (Proje No: 2012-02-04-031).

Conflicting Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lewis DB. Avian flu to human influenza. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:139–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claas EC, Osterhaus AD, van Beek R, De Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Senne DA, et al. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badur S. Epidemiolgy of Influenza. ANKEM Derg. 2006;20:256–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO): Situation update in the European Region: Overview of influenza surveillance data week 40/2009 to week 07/2010. [Last accessed 14 May 2010]. Available from: http://www.euroflu.org .

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: Novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infections-worldwide, May 6, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuite AR, Greer AL, Whelan M, Winter AL, Lee B, Yan P, et al. Estimated epidemiologic parameters and morbidity associa-ted with pandemic H1N1 influenza. CMAJ. 2010;182:131–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Cauchemez S, Hanage WP, Van Kerkhove MD, Hollingsworth TD, et al. Pandemic potential of a strain influenza a (H1N1): Early findings. Science. 2009;324:1557–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1176062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain R, Goldman RD. Novel influenza A (H1N1): Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:791–6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181c3c8f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (WHO). Clinical management of human infection with pandemic influenza (H1N1)2009. [Last accessed 21 June 2011]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/complications_guidelines/en/index.html .

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for Pharmacological Management of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza and other Influenza Viruses. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/h1n1_use_antivirals_20090820/en/index.html . [PubMed]

- 11.Smee DF, Bailey KW, Morrison AC, Sidwell RW. Combination treatment of influenza A virus infections in cell culture and in mice with the cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitor RWJ-270201 and ribavirin. Chemotherapy. 2002;48:88–93. doi: 10.1159/000057668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin M, Goldschmıdt R. Influenza management guide 2009-2010. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moscona A. Neuraminidase Inhibitors for Influenza. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1363–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) H1N1 Flu: Questions and Answers: Antiviral Drugs, 2009-2010. [Last accessed 20 May 2011]. Available from: http:// www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/antiviral.htm .

- 15.Kawai N, Ikematsu H, Iwaki N, Maeda T, Kanazawa H, Kawashima T, et al. A comparison of the effectiveness of zanamivir and oseltamivir for the treatment of influenza A and B. J Infect. 2008;56:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anovadiya AP, Barvaliya MJ, Shah RA, Ghori VM, Sanmukhani JJ, Patel TK, et al. Adverse drug reaction profile of oseltamivir in Indian population: A prospective observational study. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:258–61. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Updated Interim Recommendations fort he Use of Antiviral Medications in the Treatment and Prevention of ınfluenza for the 2009-2010 Season. [Last accessed 29 Agust 2011]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/recommendations.htm#d .

- 18.Lalezari J, Campion K, Keene O, Silagy C. Zanamivir for the treatment of influenza A and B infection in high-risk patients: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:212–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson JC, Pegram PS. Respiratory distress asssociated with zanamivir. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:661–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003023420914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]