Abstract

Introduction:

The growing field of alternative medicine has shown that dentifrices based on plant extracts are available in the market but there is little or no research to prove or refute the efficacy of dentifrices containing combination of herbal components.

Aim:

The study was conducted to evaluate the anti-plaque efficacy of a commercially available Meswak containing dentifrice compared to the conventional dentifrice using a randomized, triple blind, parallel design method.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 350 subjects were selected. All the subjects (aged 13–54 years) were given the test dentifrices, packed in plain white color-coded tubes. The subjects were instructed to brush their teeth twice daily for 2 min with the allocated dentifrice. The total study duration was 4 weeks. Plaque scores were recorded at the baseline, 2 weeks and 4 weeks respectively, using the Turesky modification of the Quigley Hein Plaque Index.

Results:

The results showed that there were significant differences in the reduction of plaque by the herbal dentifrice, Meswak (Salvadora persica) on intra-group and inter-group comparison.

Conclusion:

It was concluded that further research is required to know the dental benefits of herbal products being incorporated into the commercially available dentifrices.

KEYWORDS: Clinical trial, herbal dentifrices, Meswak, plaque index, randomized parallel design, triple blind study

The publicinterest in alternative health care, including use of natural or herbal health care products, has grown dramatically in the past few years.[1–3] In a telephonic survey of more than 1500 us adults in 1991,[4] repeated in 1997,[5] it was reported that use of alternative therapies increased from 33.8% in 1990 to 42.1% in 1997.

The growing field of alternative medicine has shown that dentifrices based on plant extracts are available in the market.[1,6] Consumers who gravitate toward using herbal products often view these products as being safer than products that contain chemicals. Dentifrices labeled as natural typically don’t include ingredients such as synthetic sweeteners, artificial colors, preservatives, additives, synthetic flavors, and fragrances. They are formulated from naturally derived components. The term Herbal on the label implies that most of a dentifrices active ingredients are plant based.[1,3]

There is little or no research to prove or refute the efficacy of dentifrices containing combination of herbal components, in contrast with a plethora of such research for conventional fluoridated ones.[1,3] The purpose of this study was to evaluate the anti-plaque efficacy of commercially available herbal dentifrice compared to the conventional fluoridated dentifrice using a randomized, triple blind, parallel design method.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a simple randomized, triple blind, parallel design, controlled clinical trial conducted to assess the anti-plaque efficacy of the selected dentifrices.

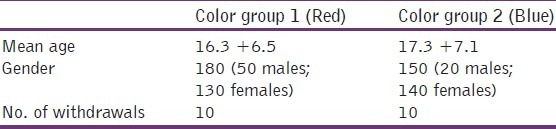

The study was conducted at a children's village and the population comprised of 350 subjects 13–54 years of age (mean age 16.71 years; [Table 1]). The sample size was calculated using previously published data. The study subjects were enrolled in the study if they met the following inclusion criteria: signing of the consent form voluntarily by the subjects and the guardians, baseline plaque score (Turesky modification) of more than 1.5, subjects not using any orthodontic appliances, the subject had not undergone antibiotic therapy at least 1 week prior to study and the presence of more than 20 scorable teeth in the oral cavity. 3rd molars were not included in the study.

Table 1.

Distribution of study participants according to age and gender

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee to conduct the study. Official permission was obtained from the President of the children's village, as well as the guardians to the children.

The clinical examination for every subject was comprehensively carried out by investigator. Prior to conducting the study, the investigator was calibrated under the guidance of the Professor in order to limit the examiner variability. The kappa co-efficient value for intra-examiner reliability with respect to the Turesky modification of Plaque Index 57 (7- superscript) was 0.85.

The examination was conducted inside a classroom, using artificial lighting. A clean and uncongested area was selected for examination to avoid crowding and noise. Examination was carried out by making the subject sit on a chair in upright position and examiner stood on the right side of the subject during the examination. The examination of a single subject took about 10 min on most of the occasion. The schedule was kept flexible in order to accommodate for unforeseen lapses.

Blinding was carried out by the study moderator blinding the subjects, the examiner, and the statistician. The test dentifrices were packed in plain white tubes (60 g each). The tubes were color coded as red and blue.

The toothpastes were allocated using the kucky draw method, wherein an equal number of colored dentifrice tubes were packed into a big polybag. The polybag contained an equal number of red and blue tubes. The study moderator carried out the allocation procedure. The subjects were asked to put their hands into the polybag and pull out a tube. The subjects were divided into groups based on the color of the tube that they pulled out.

The tubes were identical, plain tubes to ensure that neither the subjects nor the dental examiners knew the identity of the dentifrices. The dentifrices were supplied in a regular, scheduled manner throughout the course of the study. At the final visit, all remaining dentifrice tubes were collected back from the subjects to evaluate the compliance.

Subjects assigned to the test groups were provided with new toothbrushes and test dentifrice tubes and were instructed to brush their teeth twice a day for 2 min. Examinations for the plaque index[7] (Turesky modification of quigley hein plaque index, 1970) were carried out at baseline, 2 weeks and 4 weeks duration. Subjects were evaluated by the same examiner throughout the study period.

Quigley and Hein in 1962 reported a plaque measurement index that focused on the gingival third of the tooth surface. They examined only the facial surfaces of the anterior teeth, using a basic fuchsin mouthwash as a disclosing agent. A numerical scoring system of ‘0’ to ‘5’ was used. The Quigley–Hein plaque index was modified by Turesky, Gilmore, and Glickman in 1970.

This modification of the Quigley–Hein plaque index was done to strengthen the objectivity of the Quigley–Hein plaque index criteria by redefining the scores of the gingival third area. This modification is recognized as a reliable index for measuring plaque, using an estimate of the area of the tooth covered by plaque. This is a full mouth index.

The statistical analysis comprised of intra-group comparisons made with Paired t-test. Inter-group comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test for GroupWise comparisons. For all the tests, a “p” value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results

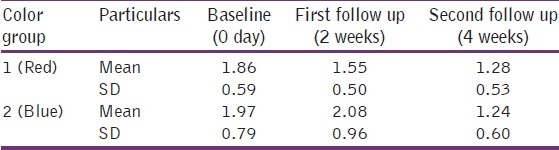

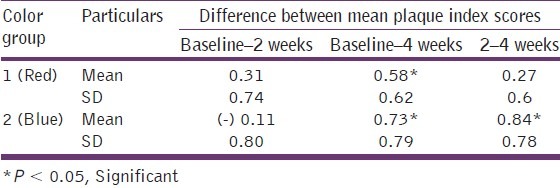

There was a significant reduction in the mean Plaque scores of the subjects of the two groups. The Red colour group showed significant reduction (P < 0.05) in plaque scores between the baseline and 4th week [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Mean PI scores for the two groups

Table 3.

Comparison of changes in mean PI scores in different groups

The Blue colour group showed an increase in plaque index scores in the first 2 weeks but then a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in plaque scores between the 2nd and the 4th weeks as well as between baseline and 4th week, respectively, was observed [Tables 2 and 3].

Discussion

The present study compared the anti-plaque efficacy of two commercially available over the counter dentifrices. A total of 350 subjects were selected to participate in the study, of which 330 subjects completed the study. The 20 participants reported unpleasant taste of the dentifrices and therefore discontinued the product.

After obtaining the results, decoding for the blinding procedure was done and it was found that the Blue color group represented the herbal group (containing Meswak as the main ingredient) and the Red color group the conventional dentifrice (containing triclosan copolymer and fluoride content of 1000 ppm).[8]

The examiner was unaware about the subject allocation into color groups, the subjects did not know which dentifrice they were using and the statistician did not know which group either color represented, therefore completing the triple blinding procedure along with randomization.

The number of dropouts in the present study was 20 (5.71%) which was lower than in the study by Prasad et al.[9] (7.25%). The dentifrices had a fair acceptance and did not show any adverse effects.

The reductions in plaque scores were not statistically significant at baseline but were so at the follow-ups for both the dentifrices. The association of tooth brushing and the test dentifrices promoted plaque reductions of 31% in the conventional dentifrice group whereas reduction was 37% in the herbal dentifrice group. Ozaki et al.[6] reported 19% reductions while Triratana et al.[10] observed reductions of 39.9% in the Plaque scores, respectively.

Batwa et al.[11] have reported that the most common type of chewing stick, Meswak, is derived from Arak tree (Salvadora persica) that grows mainly in Saudi Arabia but also in other parts of the Middle East. Meswak is a chewing stick used by many people in different cultures and in many developing countries as a traditional toothbrush for oral hygiene. The religious and spiritual impact of Meswak probably is the principal reason for using it in Islamic countries. The Meswak extract has also found its way into the dentifrices in the recent years as anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis agents.

Makarem et al.[12] have shown the efficacy of Barberry extract dental gel to be more effective in reducing dental plaque compared to a fluoride dentifrice. The same results have been reported by Chien et al.,[13] 2002, in their study on Chinese Herbal Dentifrice.

De Rysky et al.[14] and Yankell et al.[15] reported significant reduction in plaque and gingival scores at the end of their study for the subjects using Parodontax. Ozaki et al.[6] have also reported significant reduction in plaque scores and gingival scores in an intra-group comparison (Parodontax compared to Colgate Total), but there was no statistically significant difference between the groups. The results of the current study are in accordance with the findings of the above two studies as there was statistically significant reduction in plaque scores on intra-group comparison. The intergroup comparison in the current study also showed statistically significant reduction in plaque scores. This may be due to the Hawthorne effect.

Rao et al.[16] have reported improvement in plaque index, oral hygiene status, and gingival index for the patients using Himalaya Herbal Dental Cream. Prasad et al.[9] reported in their study that the reduction in plaque and gingival scores were reduced in the first half of the study. The reductions were not statistically significant. In the current study, maximum reductions were noticed in the second half of the study and were statistically significant for the herbal dentifrice group. The conventional dentifrice in the current study showed statistically significant plaque reduction but over 4 weeks of time period.

Conclusion

Although many studies are available which highlight the high anti-plaque efficacy of conventional dentifrices, no previous study has compared a herbal dentifrice containing Meswak to conventional fluoridated dentifrices, and so it is recommended that further research be conducted.

Acknowledgment

The work conducted was done independently and no financial or conflict of interest exists. We acknowledge the help of Dr. Dana Manchester, DDS, for his kind contribution to literature review.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Goldstein BH, Epstein JB. Unconventional dentistry: Part IV. Unconventional dental practices and products. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:564–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobsen PL, Epstein JB, Cohan RP. Understanding “alternative” dental products. Gen Dent. 2001;49:616–20. quiz 621-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SS, Zhang W, Li Y. The antimicrobial potential of 14 natural herbal dentifrices: Results of an in vitro diffusion method study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1133–41. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, Norlock FE, Calkins DR, Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States.Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozaki F, Pannuti CM, Imbronito AV, Pessotti W, Saraiva L, de Freitas NM, et al. Efficacy of a herbal toothpaste on patients with established gingivitis-a randomized controlled trial. Braz Oral Res. 2006;20:172–7. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242006000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine DH, Furgang D, Markowitz K, Sreenivasan PK, Klimpel K, De Vizio W. The antimicrobial effect of a triclosan/copolymer dentifrice on oral microorganisms in vitro. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1406–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad KV, Sohani R, Tikare S, Yelamalli M, Rajesh G, Javali SB. Anti-plaque efficacy of two commercially available dentifrices. JIAPHD. 2009;13:12–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.66639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Triratana T, Rustogi KN, Volpe AR, DeVizio W, Petrone M, Giniger M. Clinical effect of a new liquid dentifrice containing triclosan/copolymer on existing plaque and gingivitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:219–25. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batwa M, Bergström J, Batwa S, Al-Otaibi MF. The effectiveness of chewing stick Meswak on plaque removal. Saudi Dent J. 2006;18:125–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makarem A, Khalili N, Asodeh R. Efficacy of barberry aqueous extracts dental gel on control of plaque and gingivitis. Acta Medica Iranica. 2007;44:91–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong CH, Wei TP. The efficacy of Chinese herbal based dentifrice on the control of Plaque and Gingivitis (Abstract) J Periodontol. 2002;73:1244. [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Rysky S. The effects of officinal herbs on inflammation of the gingival margin: A clinical trial with a newly formulated toothpaste. J Clin Dent. 1988;(Suppl A):A22–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yankell SL, Emling RC, Perez B, Yankell SL, Emling RC, Perez B. Six-month evaluation of Parodontax dentifrice compared to a placebo dentifrice. J Clin Dent. 1993;4:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SH, Avinash S, Rao R, Patki PS, Mitra SK. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Himalaya Herbal Dental Cream. Antiseptic. 2008;105:601–2. [Google Scholar]