Abstract

This study proposes the inclusion of peer relationships in a life history perspective on adolescent problem behavior. Longitudinal analyses were used to examine deviant peer clustering as the mediating link between attenuated family ties, peer marginalization, and social disadvantage in early adolescence and sexual promiscuity in middle adolescence and childbearing by early adulthood. Specifically, 998 youth and their families were assessed at age 11 years and periodically through age 24 years. Structural equation modeling revealed that the peer-enhanced life history model provided a good fit to the longitudinal data, with deviant peer clustering strongly predicting adolescent sexual promiscuity and other correlated problem behaviors. Sexual promiscuity, as expected, also strongly predicted the number of children by age 22–24 years. Consistent with a life history perspective, family social disadvantage directly predicted deviant peer clustering and number of children in early adulthood, controlling for all other variables in the model. These data suggest that deviant peer clustering is a core dimension of a fast life history strategy, with strong links to sexual activity and childbearing. The implications of these findings are discussed with respect to the need to integrate an evolutionary-based model of self-organized peer groups in developmental and intervention science.

Keywords: evolutionary psychology, peer relations, sexuality, antisocial behavior, family

Adolescent problem behavior is typically considered a form of psychopathology and is accompanied by labels such as conduct disorder, delinquency, oppositional defiant disorder and disruptive behavior disorder. Concern about understanding the etiology, prevention, and treatment of problem behavior in its various forms reaches across cultural communities and generations (Schlegl & Barry, 1991). The systematic study of predictors of adolescent problem behavior in the form of longitudinal research began in the early 1900s (Loeber & Dishion, 1983). This effort to identify predictors and understand the etiology of adolescent problem behavior has been fruitful (Dishion & Patterson, 2006) and has supported the formulation of empirically validated prevention and treatment models that have shown reductions in antisocial behavior, delinquency, and substance use (Biglan, Brennan, Foster, & Holder, 2004; see Kazdin & Weisz, 2010).

Despite the progress in identifying empirical models and formulating effective intervention models, two challenges remain to our understanding of etiology and to the design of effective interventions: (a) the ubiquitous surge in problem behavior during middle to late adolescence, called the age-crime curve by criminologists (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990). Models that explain individual differences in adolescent problem behavior do not provide an adequate explanation for the increase in overall levels of problem behavior during adolescence that occurs across cultures and community contexts (Schlegal & Barry, 1996); and (b) the powerful influence of peers on adolescent problem behavior, accounting for growth and amplification of delinquency (Gold, 1970), violence (Dishion, Véronneau, & Myers, 2010; Dodge, Greenberg, & Malone, 2008), and substance use (Dodge et al., 2009; Kiesner, Poulin, & Dishion, 2010). The link between peer influence and problem behavior is more than correlational, in that randomized studies on interventions that aggregate high-risk youth reveal that peer contagion can undermine effectiveness, or worse, produce increases in various forms of problem behavior (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011; Dodge, Dishion, & Lansford, 2006).

The surge in various forms of problem behavior and the powerful influence of deviant peer activity during adolescence is not well explained by social learning processes alone (e.g., Dishion & Patterson, 2006; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). The shift in the salience of peer reward that accompanies pubertal development and associated sexual activity suggests an evolutionary perspective on developmental change in adolescence may be helpful for both understanding underlying mechanisms as well as designing more realistic and effective interventions (Ellis et al, this issue). In this article we propose an enhancement to the life history perspective on adolescent social and emotional development originally proposed by Belsky, Steinberg, and Draper (1991), hypothesizing that deviant peer clustering is a core feature of the developmental process referred to as a ‘fast’ life history strategy. We applied the peer-enhanced life history theory to test a longitudinal model for the development of adolescent problem behavior while focusing on the central role of deviant peer clustering and sexual promiscuity as the core selective adaptations that predict number of offspring by age 24. We tested this model in a sample of ethnically diverse, male and female adolescents (N = 998) initially assessed at age 11 and followed through age 23.

A Social Interaction Perspective

Social learning theories of development emphasize the analysis of social interaction experiences children have with parents and peers in the process of developing problem behavior. Observational research by Patterson and colleagues defined, measured, and established the empirical relevance of family coercive interaction dynamics in the early development of antisocial behavior (Patterson, 1982; Patterson et al., 1992). In early to middle childhood, family interactions that are inherently aversive can become a formula for coercive interpersonal dynamics in which the child learns to escalate behaviors to end conflicts (Snyder, Edwards, McGraw, Kilgore, & Holton, 1993) or to avoid onerous demands for emotional regulation (Snyder, Scherpferman, & St. Peter, 1997).

Social interaction patterns underlying the development of early antisocial behavior learned in the family increase the likelihood of a cascade of developmental sequelae that unfold once the child is in school (Shaw, Gillom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). Problem behavior in schools potentiate academic failure, peer rejection, and youth clustering into peer groups that support problem behavior (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Snyder et al., 2005) A longitudinal analysis of growth in problem behavior from middle childhood through adolescence revealed that coercive discipline practices accounted for the intercept (average levels across development) and deviant peer involvement accounted for its growth (Patterson, 1993). By early adolescence, a history of peer rejection renders youth vulnerable to peer influence, which in turn, motivates self-organization into peer groups that support problem behavior. This process of ‘social augmentation’ accounts for the emergence of gangs in early adolescence (Dishion, Nelson, & Yasui, 2005). These groups are associated with amplification of problem behavior into more serious forms, such as violence (Dishion et al., 2010; Dodge et al., 2006; Thornberry, 1998). Reinforcement principles offer a partial explanation for the social augmentation function of the deviant peer group. Low peer reinforcement in settings such as schools, rejection, or isolation can prompt youths to “shop” for more rewarding peer interactions and friendships, often organized by deviant talk, behavior, and attitudes (Dishion, Capaldi, & Spracklen, 1995).

As youth become more engaged in deviant peer groups, a concomitant and reciprocal disengagement from parental influence occurs. Antisocial youth actively avoid supervision in efforts to escape detection and supervision (Stoolmiller, 1994), and parents relinquish their efforts to monitor and socialize them. The result is “attenuated family ties” and reduced parental influence (Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004; Véronneau & Dishion, 2010). In the social interaction model, the link between family social disadvantage (i.e., socioeconomic status) and adolescent problem behavior is mediated through the effects of peer marginalization (Dishion et al., 1991) and attenuated family ties (Forgatch, Patterson, & Skinner, 1988; Larzelere & Patterson, 1990; Patterson et al., 1992). As mentioned previously, the empirical success of the social interactional perspective on adolescent problem behavior is noteworthy with respect to the design of effective interventions. However, it is limited primarily for addressing the surge of problem behavior in adolescence and also in terms of the bias toward peer influence for marginalized youth in early to middle adolescence.

Life History Perspective

Life history framework is a model of development that integrates environmental disruption with an evolutionary perspective on development (Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, &Schlomer, 2009). Belsky et al. (1991) initially used the life history framework to understand individual differences in child and adolescent social and emotional adjustment and emphasized female development, puberty, and early sexual promiscuity. The concept is that stressful early child-rearing environments, especially those characterized by harshness and unpredictability (e.g., social disadvantage, marital instability, family conflict) evoke “fast” life history strategies, which are characterized by early menarche, early sexual involvement, and early and frequent childbearing and low-investment parenting. In contrast, safe, secure, and predictable child-rearing environments (e.g., adequate socioeconomic resources, marital stability, supportive parent–child relationships) promote “slow” life history strategies characterized by later onset sexual behavior, later puberty, enduring monogamous relationships, fewer and later offspring, and high-investment parenting strategies.

Introduction of the life history framework to developmental psychology opened the door to novel hypotheses regarding the links between childhood experiences, tempo of pubertal development, and concomitant reproductive strategies (see Belsky et al., 1991; Ellis et al., 2009). The life history framework was recently applied to a longitudinal sample of females followed from early childhood through adolescence. In support of life history theory, the researchers found that maternal harshness at age 5 predicted the child’s early menarche, which in turn predicted sexual risk taking and other problem behaviors, such as substance use (Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, & Halpern-Felsher, 2010; see also James, Ellis, Schlomer, & Garber, this issue). The model fit the data for females, but a model for males has not yet been tested.

A significant omission from the life history framework is the function of peer clustering in early to middle adolescence with regard to regulating reproductive strategies. As described earlier, children and adolescents tend to self-organize into peer groups based on similarities of attitudes, behavior, and circumstances, and those interpersonal dynamics of “peer contagion” tend to amplify various forms of problem behavior (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). Most important for a life history perspective, deviant peer clustering has been found to consistently be the strongest predictor of early and promiscuous sexual activity in adolescence, over and above pubertal maturation of males or females (Capaldi, Crosby, & Stoolmiller, 1996; French & Dishion, 2003). High peer group status is important in several primate species (de Waal, 2006). Primate studies demonstrate that peers not only serve a repair function for maternal deprivation (Suomi & Ripp, 1983), but also as a socialization nexus between early maternal rearing and adolescent mate selection and production of offspring (Kohler & Gumerman, 2000; Sameroff & Suomi, 1996).

Pellegrini and colleagues completed a creative longitudinal study following 138 early adolescence males and females during their first 2 years of public middle school (Pellegrini & Long, 2003). Of interest were the peer dynamics among males and females that defined the basis for dating popularity in early adolescence. In their analysis the researchers included observable behaviors such as “poking” play during unstructured school hours, as well as peer nominations of “relational aggression,” “dominance,” and “dating popularity.” The study found that for girls, high levels of relational aggression accompanied increases in dating popularity, whereas for boys, high levels of dominance accompanied increases in dating popularity. Consistent with sexual selection theory (e.g., Trivers, 1972), these results suggest that intrasexual competition was played out by gender-specific forms of problem behavior, which in turn increased the likelihood of sexual relationships in early adolescence.

If self-organization into peer groups is critical to sexual selection, a developmental history of marginal peer relationships and attenuated family ties may be particularly salient as a promotive condition for the formation of deviant peer groups. A relatively underemphasized dimension of environmental threat for human and nonhuman primates is exclusion, marginalization, and rejection (de Waal, 2009). Evidence suggests that threats of rejection, even during simple lab tasks, elicit strong reactions of emotional distress as evidenced by amygdala activation (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003). Therefore, a sense of isolation, exclusion, and social disadvantage may elicit mutual interest in forming subgroups among youth with similar circumstances.

Early adolescence may be a particularly critical period for concerns of social inclusion and exclusion. Physiological changes in the developing brain during adolescence suggest the importance of peers. The primacy of the peer group in adolescence is supported by a shift in the physiological substrate and in cortical processing that affects the salience and experience of social rewards (Spear, 2010). Several patterns of neuroanatomical response indicate increased processing of social reward during adolescence (Dahl, 2004; Fareri, Martin, & Delgado, 2008; Spear, 2000), which suggests an enhanced desire and potential for peer group affiliation. The consequences of peer marginalization and attenuated family ties, therefore, may be particularly salient motivations for the formation of deviant peer clusters, as has been found in the longitudinal research (Dishion et al., 1991; Dodge et al., 2008) and in studies on the prediction of gang involvement in adolescence (Dishion et al., 2005).

From a broader perspective, youths can be marginalized by virtue of the socioeconomic status (SES) of their family. SES is often modeled as a disruptor of family socialization processes (Conger et al., 1992; Conger et al., 2002). However, in studies of peer relationships, SES of the child has often emerged as an independent predictor of peer rejection (Bierman, 2004; Kupersmidt & Coie, 1990) and of clustering into deviant peer groups (Dishion et al., 1991) and gangs (Farrington, 1988; Hill, Howell, Hawkins, & Battin-Pearson, 1999; Lahey, Gordon, Loeber, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Farrington, 1999; Short, 1990). Thus, we expect that family SES is associated with marginalization by peers and with deviant peer clustering in early adolescence.

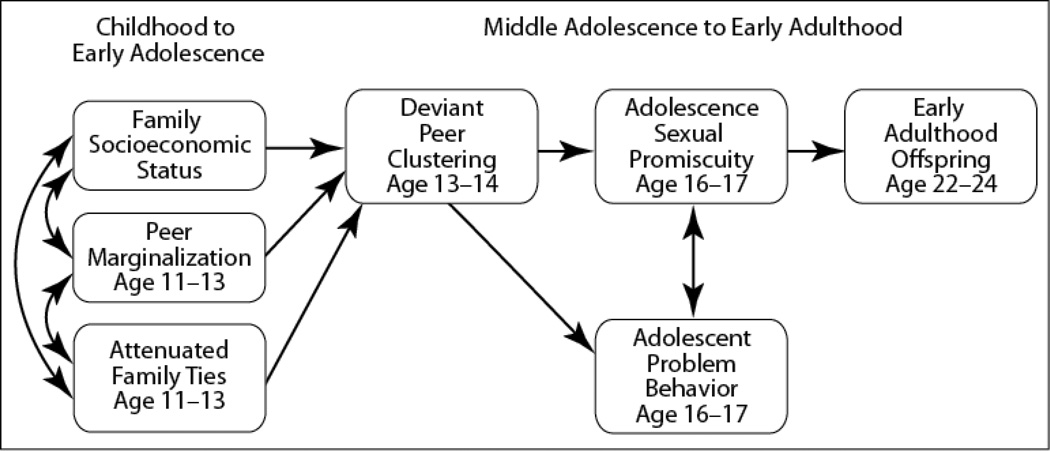

As shown in Figure 1, a peer-enhanced life history framework suggests the hypothesis that attenuated family ties, peer marginalization, and social disadvantage motivate deviant peer clustering, which is the key factor predicting adolescent sexual promiscuity and childbearing in early to late adolescence. In this framework and in the social interactional model, adolescent problem behavior is hypothesized to be a by-product of deviant peer clustering and only correlated with sexual promiscuity.

Figure 1.

An overview peer enhanced life history model progeny.

This shift in perspective suggests that marginalized peer environments, attenuated family ties, and low SES evoke motivation to self-organize into deviant peer groups. Limited social resources related to SES and long-term viability within a community suggest short-term strategies for gaining access to rewarding social interactions with peers, and ultimately, for promoting early achievement of sexual and familial milestones. Figure 1 summarizes an evolutionary perspective on the role of deviant peer clustering in sexual promiscuity and early-adulthood progeny. In this model, pubertal development is expected to covary with the motivation to self-organize in deviant peer clusters for youth marginalized by peers and with attenuated family ties.

In summary, the peer enhancement of the life history perspective proposes the following set of hypotheses:

The strongest predictor of adolescent promiscuous sexual activity at age 16 and 17 is male and female involvement with deviant peers at age 13 and 14, controlling for pubertal development at the same age.

Marginalization by the overall peer group, attenuated family ties, and low SES will independently predict early-adolescence involvement with deviant peers.

The link from peer marginalization, attenuated family ties, and SES to sexual promiscuity will be entirely mediated by early involvement with deviant peers.

Young adult (age 22 to 24) childbearing will be best predicted by adolescent sexual promiscuity, and the effects of all other predictors will be mediated by adolescent sexual promiscuity.

Method

Participants

Study participants included 998 adolescents and their families, recruited in sixth grade from three middle schools in an ethnically diverse metropolitan community in the northwest region of the United States. These participants formed a community-based sample in that the schools involved in this study were representative of middle schools in this community and were not part of a high-risk neighborhood. Parents of all sixth grade students in two cohorts were approached for participation, and 90% consented. The sample included 526 males (52.8%) and 471 females (47.2%). By youth self-report, the sample comprised 423 European Americans (42.4%), 291 African Americans (29.2%), 68 Latinos (6.8%), 52 Asian Americans (5.2%), and 164 (16.4%) youths of other ethnicities, including mixed ethnicity. The final sample comprised two recruitment cohorts recruited from the same schools. Cohort 1 represented 95% and Cohort 2 represented 90% of the community sample. Recruitment occurred in two stages: the first stage involved active consent for a light assessment at school, and the second stage involved collection of parent, youth, and direct observation reports at Wave 6. At the first stage, 90% of participants who were approached, participated. The second stage yielded 81% retention of the original sample.

Parent reports collected when their adolescent was 16 years old revealed that 39.6% of participants lived with both genetic parents, 43.8% lived with their biological mother, 6.7% lived with their biological father, and 10.0% lived in other family configurations. The median range of gross annual household income was $30,000 to $39,999, with 25.3% of households earning less than $20,000 per year and 12.7% earning more than $90,000.

This study was part of a larger project that included a randomized intervention component following the Family Check-Up model (Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003). Youths were thus randomly assigned at the individual level to either the control group (498 youth) or the intervention group (500 youth) in the spring of sixth grade. Public schools agreed to randomization of students to the intervention to increase the range of services available to students in their schools.

Because most participants remained in the same middle school from Wave 1 through Wave 3, and because data collection took place in the school setting, a high rate of retention was maintained on the light assessment across the first three waves. Most participants were streamed into a few local high schools whose principals agreed to help us track participants, which greatly facilitated data collection at Wave 6. Such procedures, however, were not sufficient for participants who stopped attending the schools involved in our study, and these procedures were not useful at Wave 9, after participants graduated from high school. Additional procedures were therefore put in place; namely, at each wave of data collection, participants were asked to fill out a form with their current contact information (mailing address, phone numbers) and to provide the contact information of other people (e.g., friends, family members) who could eventually help us find them if they had moved before the next wave of data collection. Participants were also paid $5 for sending us their new contact information when they moved. Under those circumstances, questionnaires that were usually filled out in school could be filled out at home and mailed back to us. Together, these longitudinal retention procedures were very efficient, with approximately 80% of youth being retained across the study span (once across Waves 1 through 3, N = 998; Wave 3 only, N = 854; Wave 6, N = 804; Wave 9, N = 855).

Intervention Protocol

Half of the study sample were randomly assigned to a family-centered ecological approach to family intervention and treatment (EcoFIT). Although potential intervention effects were not a focus of this study, we tested for differences in the results across the intervention and control group, so a brief description of this program is in order. The intervention, described in greater detail elsewhere (Connell, Dishion, Yasui, & Kavanagh, 2007; Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003; Dishion & Stormshak, 2007; Dishion, Stormshak & Kavanagh, 2011), is a multilevel, ecological approach implemented in the context of the public school environment.

Assessment Procedures

During middle school (Waves 1 through 3), student self-report surveys, peer nominations, teacher ratings, and school counselor ratings were collected in the school context. Student self-report surveys and teacher ratings were administered in the high school setting at Wave 6, and parents also filled out a questionnaire that they mailed back to our research office. Questionnaires to be completed by participants at Wave 9, when participants were on average 23 years old, were sent directly to their homes and were returned to our research office by mail. The student self-report survey was an adaptation of an instrument developed and reported by colleagues at Oregon Research Institute (Metzler, Biglan, Ary, & Li, 1998). If students moved out of their original schools, they were followed to their new location. Students were paid $20 for completing surveys at each assessment wave. Each year, teachers completed the Teacher Risk Screening Index (Soberman, 1994; see also Dishion & Kavanagh, 2003), a screening measure used to identify youth at risk for problem behavior in middle school.

Light assessments (youth survey, teacher ratings, peer nominations) were collected on all study participants at Waves 1 to 3. To evaluate the effects of the randomized intervention, two more levels of assessment were collected: one from at-risk students, and another from high-risk students. If a student was identified as at-risk by teachers in the sixth grade, families were asked to complete another set of assessments. Assessment of puberty was included in this set, and it was available for nearly half of the participants in the light assessment group (i.e., those who were deemed as at risk). At Wave 6 and thereafter, all the participants were assessed on all measures.

Measures

Most of the variables used in our model were latent variables based on two or more indicators. Means and standard deviations of all indicators are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Each Measure

| Male | Female | European American |

African American |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.03 | 0.70 | −0.03 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.57 | −0.37 | 0.72 |

| Peer Marginalization | ||||||||||

| Peer nominations | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 0.99 | −0.10 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.12 | 0.93 |

| Teacher report | 1.89 | 0.85 | 2.08 | 0.90 | 1.68 | 0.75 | 1.85 | 0.90 | 2.03 | 0.85 |

| Family Attenuation | ||||||||||

| Positive relations | 3.47 | 0.86 | 3.48 | 0.84 | 3.45 | 0.88 | 3.43 | 0.80 | 3.57 | 0.90 |

| Parental monitoring | 3.96 | 0.80 | 3.88 | 0.79 | 4.06 | 0.79 | 4.09 | 0.70 | 3.90 | 0.86 |

| Family conflict | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 1.06 | 0.94 |

| *Pubertal Maturation | 0.69 | .29 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.23 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 0.29 |

| Deviant Peer Clustering | ||||||||||

| Teacher report | 1.87 | 1.22 | 2.00 | 1.29 | 1.72 | 1.13 | 1.63 | 1.06 | 2.01 | 1.29 |

| Self-report | 1.39 | 1.03 | 1.39 | 1.01 | 1.40 | 1.04 | 1.19 | 0.76 | 1.48 | 1.05 |

| Counselor report | 1.24 | 0.51 | 1.30 | 0.58 | 1.18 | 0.40 | 1.08 | 0.31 | 1.36 | 0.50 |

| Peer nominations | 1.65 | 4.13 | 2.17 | 5.20 | 1.10 | 2.43 | 0.98 | 2.27 | 1.85 | 2.80 |

| Adolescent Sexual Promiscuity | ||||||||||

| Early sexual activity | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.73 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 1.11 |

| Number of partners | 0.93 | 2.32 | 1.10 | 2.55 | 0.76 | 2.05 | 0.75 | 2.23 | 1.28 | 2.99 |

| Unsafe sex | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Adolescent Problem Behavior | ||||||||||

| Parent report | 3.36 | 3.20 | 3.46 | 3.31 | 3.26 | 3.09 | 3.26 | 3.04 | 3.24 | 3.06 |

| Self-report | 1.30 | 0.39 | 1.33 | 0.38 | 1.27 | 0.39 | 1.31 | 0.41 | 1.27 | 0.35 |

| Teacher report | 2.59 | 1.79 | 2.84 | 1.88 | 2.34 | 1.66 | 2.21 | 1.57 | 3.01 | 1.92 |

| Early Adult Progeny | ||||||||||

| Number of pregnancies | 1.02 | 1.51 | 0.88 | 1.47 | 1.16 | 1.54 | 0.63 | 1.29 | 1.53 | 1.77 |

| Number of children | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

Note.

The pubertal maturation variable was computed on a non-random subsample and was only used for post hoc analyses.

Peer marginalization (Waves 1–3, age 11–13)

Peer marginalization was a latent variable measured from a combination of two indicators, one reported by peers and one reported by the teacher. First, we used peer nominations of disliked grade mates to assess rejection. Counts of these nominations for each youth provided scores of how disliked a youth was by school peers. These scores then were standardized to account for the different numbers of students making peer nominations in each school. Second, we used one item from the teacher’s report (other kids dislike him or her), which was scored on a scale ranging from 1 (never/almost never) to 5 (always/almost always). Both indicators (peer nomination and teacher rating) were mean scores based on ratings obtained at Waves 1, 2, and 3.

Attenuated family ties (Waves 1–3, age 11–13)

This latent variable was measured from a combination of three youth-report indicators. For each of these three scales, an average score based on data collected at Waves 1, 2, and 3 was created and used as an indicator in the model. The first scale, Positive Family Relations, included statements such as “I really enjoyed being with my parents,” “My parents trusted my judgment,” “Family members back each other up.” Each item was scored on a scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true) relevant to the past month, and a mean score was created from the six items (α = .89 to .90). The second scale, Parental Monitoring, included five items asking the youth how often their parents knew what they were doing away from home, where they were after school, what their plans were for the next day, and what were their interests, activities, and whereabouts. Each item was scored on a scale ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always to almost always), and a mean score was created based on all five items (α = .85 to .87). The third scale, Family Conflict, included five items reflecting the frequency with which family members engaged in conflict behaviors, such as getting angry with each other and arguing at the dinner table. Each item was scored on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (more than seven times), and a mean score was created based on all five items (α = .77 to .81).

Pubertal maturation (Wave 3, age 13–14)

Our measure of sexual maturation was available only for a nonrandom subsample of participants (n = 405) who were rated as at risk for development of problem behavior on the basis of teachers’ report in Grade 6 (as explained earlier). Using the Physical Development Questionnaire (Peterson & Taylor, 1980), adolescents reported their own observations of physical changes (M age = 13 years and 9 months old; SD = 5 months). Three questions that were identical for boys and girls asked about growth spurt in height, growth of body hair, and skin changes. Boys were asked two additional questions about deepening of their voice and growth of their facial hair. Girls were asked two additional questions about the growth of their breasts and about their menarche. All items were coded either 0 (not yet started or has barely started) or 1 (is definitely underway or seems completed). Menarche was coded 0 (no) or 1 (yes). Items were averaged to yield a global score (α = .65 for boys and .54 for girls).

Socioeconomic status (SES)

SES was measured using a combination of parents’ reports about their employment status, education, income, housing status, and financial aid to the family. We used the highest score based on both primary caregivers when participants were from two-parent families for parental employment (full-time or self-employed [coded 4]; part time [3]; seasonal [2]; disabled, unemployed, temporary layoff, homemaker, retired, or student [1]) and parental education (graduate degree or college degree [coded 5], junior college or partial college [4], high school graduate [3], partial high school or junior high completed [2], and 7th grade or less or no formal schooling [1]). Only one global score was used for the other indicators, that is, family housing (own your home [(coded 5], rent your home [4], motel/temporary [3], live with a friend or live with a relative [2], and emergency shelter or homeless [1]), household income ($90K or more [coded 7], between $70K and $90K [6], between $50K and $70K [5], between $30K and $50K [4], between $20K and $30K [3], between $10K and $20K [2], and less than $10K [1]), and financial aid (sum of dichotomous indicators of whether the family received food stamps, Aid to Dependent Children, other welfare, medical assistance, and Social Security death benefits, reverse coded). These variables were standardized and averaged (α = .71). This measure was based on data collected in middle adolescence, because only a small subset of “at-risk” participants had answered such questions in middle childhood to early adolescence. Still, a strong correlation (r = .72) existed between the SES measure obtained early on and the one measured in middle adolescence, based on the 328 participants who provided this information at both times. This means that SES indicators are quite stable over time, so we were confident that the middle-adolescence SES measure was as good a proxy for SES as it would have been at the beginning of the study.

Deviant peer clustering (Wave 3, age 13–14)

This latent variable was measured using four separate indicators. Teachers rated each student on one item asking about their perception of students’ involvement with deviant peers (i.e., hangs around with troublemakers), with scores ranging from 1 (never, almost never) to 5 (always, almost always). We also used one item from the self-report survey asking participants whether they had spent time with gang members as friends during the past month, with scores ranging from 1 (never) to 20 (more than 20 times). In addition, school counselors provided ratings for each student about whether the adolescent was perceived to be a part of gang-involved crowds (i.e., To what extent is [name] part of the crowd who likes gangs?), on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). Last, peers’ crowd nominations supplied a measure of whether each youth was perceived as part of a gang by classmates (classmates rated, To what extent does [name] hang out with gang members?). Because the size of grade populations differed, a proportion score was calculated on the basis of number of nominations of gang involvement and number of classmates, with a range of 0 (no nomination) to .50 (nominated by half of one’s classmates).

Adolescent sexual promiscuity (Wave 6, age 16–17)

This latent construct was based on three self-report indicators. The first indicator is derived from two questions, one asking participants whether they had ever had sexual intercourse, and the other asking about their age when it first occurred, if applicable. Participants who were not yet sexually active received a score of 0, and other participants received a score of 1 if they had their first intercourse at age 16 or 17, a score of 2 if it was at age 14 or 15, and a score of 3 if it was at age 13 or earlier. The next indicator was based on a question asking about the number of sexual partners of the opposite sex participants had in the past year. The last indicator was a binary item (Yes/No) indicating if the adolescent engaged in unsafe sexual practices that could lead to pregnancy, based on whether they ever had sexual intercourse and how often they used a contraceptive method.

Problem behavior (Wave 6, age 16–17)

The three indicators used for the problem behavior latent variable came from parent, self, and teacher reports. First, parents were presented with a series of 15 items describing various externalized problem behaviors (e.g., arguing or talking back to an adult; screaming, yelling, or shouting at someone; physically fighting with someone; telling a lie), and they were asked whether their child had exhibited those behaviors during the past 3 months. Parents answered with either Yes or No. If more than one parent (or parental figure) answered this question, the answers of all informants were averaged for each item. A sum was then computed, with a possible range of 0 to 15 (α = .65). Second, adolescents reported about their own problem behaviors during the past month by responding to a set of nine items (e.g., stayed out all night without permission, intentionally hit or threatened to hit someone at school, carried a weapon). Each item was scored on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times), and the items were averaged to yield a global score (α = .73). Last, teachers rated their students by using a set of 13 items describing problem behaviors (e.g., behaves irresponsibly, disturbs other students, is physically aggressive with other students) using a scale ranging from 1 (frequent, clear signs) to 10 (no problems). All items were averaged to create a global score (α = .95).

Early-adulthood child bearing (Wave 9; age 23–24)

For the first indicator, we used participants’ report on how many times they had been pregnant or had impregnated another. For the second indicator, participants were asked whether they had children, and for each child (maximum four) they were asked a series of questions, including whether they were the genetic parent of the child, which is more speculative for males than for females. The number of children of whom participants reported being the birth parent was then calculated. Only four participants reported having four biological children, so it is unlikely that a ceiling effect affected the distribution of this variable. Some participants who did not participate at the Wave 9 assessment had provided information about their children at a previous wave, and we included the number of children they had previously reported.

Gender

Child gender was coded as 0 = “male” and 1 = “female.”

Ethnicity

Youth-reported ethnicity was coded as 0 = “European American” and 1 = “ethnic minority.”

Analytic Strategy

Multiagent structural equation models were estimated using Mplus software version 6. Missing values were present in the dataset because of the longitudinal nature of the research design, but adequate covariance coverage was present (.72 on average, with a range of .48 to .99, based on all variables except pubertal maturation). Missing data in all models were managed with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure used by Mplus version 6. This method has been shown to be very efficient when analyzing data from samples with moderate levels of missing values, and it is adequate even when data are not missing at random, as long as the predictors of missing data are included in the model (Widaman, 2006). When using FIML, the estimation of each parameter is conducted on the basis of all available information from each participant. Consequently, we can retain in the analysis participants with occasional missing data so they contribute to model estimation.

Our strategy to compare alternative models, used to examine the generalizability of the model across genders, ethnic groups, and intervention groups, was based on comparison of the comparative fit index (CFI). In fact, the change in CFI (Δ CFI) is recommended when the analyses are based on a large sample, because traditional chi-square difference tests tend to be overly sensitive to sample size and may lead to overestimating the significance of the differences existing between two models. According to Cheung and Rensvold (2002), Δ CFI of .01 or greater indicates a significant difference between two models.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents means and standard deviants for the overall sample and also separately by gender, ethnic groups (European Americans versus African Americans only), and the randomized intervention groups. Group differences for variables that we had planned to use together as indicators of a latent variable were explored using MANOVAs, whereas group differences for other variables were explored using t tests. Regarding gender differences, the MANOVA revealed that males experienced more marginalization by peers than did females, F(2, 987) = 28.91, p < .001, and tests of between-subject effects revealed that both indicators (peer and teacher reports) were significantly different across groups. Males were more likely than females to self-organize into deviant peer clusters, F(4, 605) = 5.60 p < .001, and this difference was significant for peer nominations, teacher ratings, and school counselor ratings (not for self-reports). The multivariate effect for indicators of sexual promiscuity was marginally significant, F(3, 723) = 2.48, p = .06, and only one indicator was marginally significant, because males reported larger numbers of sexual partners than did females (no differences for the age of initiation of sexual activity or unsafe sex practices). Males were also more likely to engage in problem behavior, F(3, 584) = 5.38, p < .001, but only teacher reports accounted for this difference (not self- or parent reports). Family experiences differed across genders, F(3, 993) = 8.27, p < .001, and females’ reporting of higher levels of parental monitoring accounted for this difference (not the positive relations or the family conflict indicators). The multivariate effect of early-adulthood progeny was also significant, F(2, 744) = 11.86, p < .001, and both indicators (number of pregnancies and number of children) revealed that females were more advanced than were males in this aspect of their adult life. This difference, however, may reflect male ignorance of their offspring. Regarding pubertal maturation, consistent with other research (Dahl, 2004), we found that females were more advanced than were males, t(403) = −7.29, p < .001. No gender difference emerged on SES, measured with a single observed variable.

Regarding ethnic differences, the MANOVA revealed significant yet inconsistent differences on indicators of attenuated family ties, F(3, 710) = 20.39, p < .001. Specifically, European Americans reported experiencing more monitoring from their parents, whereas African Americans reported higher levels of positive family relations and family conflicts. We also found an overall significant difference in levels of peer marginalization, F(2, 706) = 3.76, p < 05, but this difference was restricted to teacher report and varied significantly across groups (not the peer nominations). There was a significant difference in deviant peer clustering, F(4, 438) = 14.47, p < .001, and increased levels for African American students were accounted for by all four indicators (self-report, peer report, teacher ratings, and counselor ratings). The MANOVA also revealed group differences in adolescent sexual promiscuity, F(3, 536) = 12.391, p < .001, which were accounted for by African American youths’ earlier initiation of sexual activities and greater number of sexual partners, but no differences emerged for unsafe sexual practices. Although a significant difference emerged for adolescent problem behavior, F(3, 453) = 8.34, p < .001, it was explained only by teachers’ reporting more problem behavior for African Americans; no differences emerged for parent and self-report. There were group differences in child bearing by early adulthood, F(2, 541) = 33.03, p < .001, with African Americans reporting more pregnancies and more children than European Americans reported. Pubertal maturation was marginally more advanced for African American youth, t(304) = −1.78, p = .08, and European Americans had higher SES levels, t(550) = 12.51, p < .001.

When comparing the control and intervention groups, we found significantly lower levels of problem behavior for the intervention group than for the control group. This finding is consistent with studies specifically evaluating the impact of the randomized Family Check-Up on subsequent problem behavior in adolescence (e.g., Connell et al., 2007, Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2003).

A missing-value analysis was conducted using the PASW (SPSS) software version 18.0.2. The Little’s MCAR test conducted on all measures (excluding pubertal maturation, which was administered only to the at-risk subsample of participants, and categorical variables, i.e., gender, ethnicity, treatment group) revealed that the pattern of missing values was not completely random, χ2(1957) = 2628.82, p < .001. To understand the missing data patterns, we created a measure of missing data that represented the number of indicators used in the model for which we had no valid data (an occasional failure by any informant to answer one question in a scale was not counted as missing data, because average scale scores were computed). A lower score on family SES, parental monitoring, and being a male predicted a larger number of missing values. Also, a larger number of missing values was related to higher scores on teacher-rated peer marginalization and deviant peer clustering; self-report of deviant peer clustering; parent- and teacher-reported problem behavior; earlier sexual activity; number of sexual partners, pregnancies, and born children; and being a member of an ethnic minority group. The significant correlations between the number of missing values and these variables were mostly in the small range, that is, all r ≤ .26.

Model Testing

Table 2 presents the zero order correlation among all the variables in the model. For the entire sample, and in general, variables were intercorrelated in the expected direction. The model in Figure 1 was tested using structural equation modeling, with evaluation of the indices of fit based on the a priori model and then post hoc analyses of fit. According to Kline (2005), a good model fit should yield a nonsignificant chi-square value, but this test tends to be too conservative with larger sample sizes (e.g., greater than 200). In that case, other fit indices are usually preferable for assessing model fit. CFI and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) values at .90 or more, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values at .06 or less, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values at .10 or less indicate adequate model fit.

Table 2.

Correlations Among All Measures

| SES | Peer Marginalization |

Family Attenuation |

aPubertal Maturation |

Deviant Peer Clustering | Adolescent Sexual Promiscuity |

Adolescent Problem Behavior |

Early Adult Progeny |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer nomin |

Teach report |

Pos rel |

Parent monit |

Fam conflict |

Teach report |

Self- report |

Couns report |

Peer nomin |

Early sex |

No. partners |

Unsafe Sex |

Parent report |

Self- report |

Teach report |

Number preg. |

|||

| SES | - | |||||||||||||||||

| Peer Marginalization | ||||||||||||||||||

| Peer nominations | −.04ns | – | ||||||||||||||||

| Teacher report | −.24 | .46 | – | |||||||||||||||

| Family Attenuation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Positive relations | .01 ns | −.08** | −.07* | – | ||||||||||||||

| Parental monitoring | .16 | −.05ns | −.09** | .51 | – | |||||||||||||

| Family conflict | −.15 | .15 | .14 | −.41 | −.33 | – | ||||||||||||

| aPubertal Maturation | .04ns | .06ns | .01ns | .05ns | .03ns | .05ns | – | |||||||||||

| Deviant Peer Clustering | ||||||||||||||||||

| Teacher report | −.27 | .22 | .42 | −.15 | −.23 | .12 | .04ns | – | ||||||||||

| Self-report | −.14 | .10** | .13 | −.13 | −.25 | .23 | .04ns | .19 | – | |||||||||

| Counselor report | −.29 | .14 | .21 | −.04ns | −.19 | .13 | .13* | .38 | .34 | – | ||||||||

| Peer nominations | −.11* | .13 | .14 | −.04ns | −.18 | .09* | .12* | .31 | .39 | .56 | – | |||||||

| Adolescent Sexual Promiscuity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Early sexual activity | −.26 | .14 | .17 | −.16 | −.21 | .22 | .13** | .24 | .20 | .28 | .17 | – | ||||||

| Number of partners | −.16 | −.16*** | .13*** | −.10** | −.12 | .11** | .10† | .20 | .12** | .16 | .15 | .43 | – | |||||

| Unsafe sex | −.05 | .08* | .10** | −.14 | −.18 | .09* | .07ns | .15 | .08* | .09* | .02ns | .22 | .11** | – | ||||

| Adolescent Problem Behavior | ||||||||||||||||||

| Parent report | −.14 | .22 | .27 | −.15 | −.16 | .24 | −.01ns | .22 | .13 | .18 | .13** | .25 | .15 | .04ns | – | |||

| Self-report | −.02 ns | .17 | .12 | −.15 | −.22 | .21 | .09† | .11** | .20 | .06ns | .10* | .22 | .18 | .06ns | .26 | – | ||

| Teacher report | −.29 | .32 | .47 | −.08* | −.20 | .18 | −.12* | .29 | .13 | .20 | .03ns | .22 | .16 | .03ns | .34 | .22 | – | |

| Early Adult Progeny | ||||||||||||||||||

| Number of pregnancies | −.32 | .09* | .13 | −.10** | −.15 | .12** | .02ns | .19 | .17 | .14 | .11* | .34 | .22 | .16 | .16 | .12 | .21 | |

| Number of children | −.36 | .10** | .13 | −.07* | −.11 | .10** | −.04ns | .21 | .20 | .23 | .16 | .33 | .20 | .19 | .17 | .07† | .20 | .66 |

Note. SES = socioeconomic status

All correlations are significant at p < .001, unless otherwise indicated.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10,

nonsignificant.

The pubertal maturation variable was computed on a nonrandom subsample and was used only for post hoc analyses.

Fit statistics for successive model testing are presented in Table 3. First, we tested the a priori model in the original, unadjusted form. We used several comparative fit indices, including the TLI, χ2 statistic, Akaike information criteria (AIC), and Bayesian information criteria (BIC). The model fit indices indicate that the peer-enhanced life history model provided an adequate fit to the data, except for the TLI (.87) and the χ2 statistic, although the latter tends to be too conservative for larger samples.

Table 3.

Goodness of Fit Statistics for Each Model

| χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted models | 440.69 | 122 | <.001 | .90 | .87 | .05 (.05–.06) | .06 | 38262.29 | 38590.98 |

| Adjusted models | 369.65 | 120 | <.001 | .92 | 90 | .05 (.04–.05) | .05 | 38195.25 | 38533.75 |

We then inspected modification indices and made post hoc changes to the model. Specifically, we included a direct path from SES to early-adulthood child bearing and another one from peer marginalization to adolescent problem behavior. The first effect is consistent with a general life history perspective (see Belsky et al., 1991; Ellis et al., 2009). This yielded an adequate fit, according to all indices (except χ2 statistic). These modifications together yielded a significant improvement in fit, Δ CFI = .02.

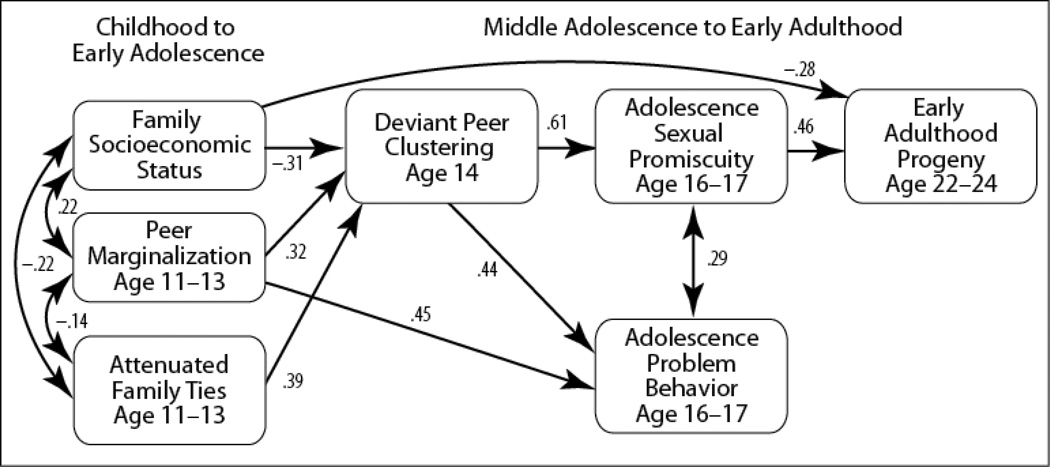

The final model is represented in Figure 2; factor loadings are reported separately, in Table 4. All paths presented in Figure 2 are statistically reliable. Also, the indirect effects from all three childhood–early adolescence predictors (SES, family attenuation, and peer marginalization) to early-adulthood child bearing are significant at p < .001 (standardized coefficients = −.09, .11, and .09, respectively).

Figure 2.

Results of the final peer enhanced Life history model. See Table 3 for factor loadings.

Table 4.

Factor Loadings for Each Indicator in the Final Model

| Indicator | λ |

|---|---|

| Peer marginalization | |

| Peer nominations | .56 |

| Teacher report | .80 |

| Attenuated Family Ties | |

| Positive relations | −.71 |

| Parental monitoring | −.71 |

| Family conflict | .53 |

| Deviant peer clustering | |

| Teacher report | .59 |

| Self-report | .44 |

| Counselor report | .66 |

| Peer nominations | .46 |

| Adolescent sexual promiscuity | |

| Early sexual activity | .79 |

| Number of partners | .52 |

| Unsafe sex | .28 |

| Adolescent problem behavior | |

| Parent report | .51 |

| Self-report | .35 |

| Teacher report | .71 |

| Early adult progeny | |

| Number of pregnancies | .80 |

| Number of children | .80 |

Note. All factor loadings are significant at p < .001.

We then tested our hypothesis that the association between the three initial predictors (attenuated family ties, peer marginalization, and SES) and sexual promiscuity was entirely mediated by deviant peer clustering. To do so, we created a partial mediation model in which three residual links were modeled to predict sexual promiscuity. The partial mediation model did not fit the data significantly better than did the more parsimonious full mediation model, as revealed by a nonsignificant Δ CFI, thus supporting the full mediation hypothesis.

Group Differences

It is reasonable to hypothesize that the developmental process would vary by gender, ethnicity, or intervention group. To assess the significance of the difference between various groups, we first ran a multiple-group “constrained” model in which the two groups are assumed to have equivalent regression and correlation paths and then a multiple group “unconstrained” model in which the groups are not assumed to have identical regression and correlation paths. The CFI obtained for each model was then used to compute the Δ CFI that revealed whether differences across groups were significant.

Gender

The fit of the unconstrained model was better than the fit of the model for which all regression and correlation coefficients were constrained to equality across boys and girls, as revealed by a Δ CFI of .029. The modification indices suggested that the constraint placed on the correlation between the residual errors of the peer-reported and the counselor-reported items loading on the deviant peer clustering construct should be free to vary across genders, which turned out to be significant only for males. Also, for the male subsample, we allowed for a correlation between the error terms of two items loading on the sexual promiscuity construct (the number of sexual partners and early sexual activity). After releasing these two constraints, the Δ CFI between the two models was no larger than .01. We thus concluded that the overall model fits equally well for males and for females, because it was not necessary to change the basic structural coefficients across gender.

Ethnicity

The two largest ethnic groups were African American and European American, for which the model was compared. The fit of the unconstrained model was slightly better than the fit of the constrained model, as revealed by a Δ CFI of .013. The modification indices suggested that the intercept of the Family Relation scale, used as an indicator for the attenuated family ties construct, should be allowed to differ across the European Americans and African Americans. (Means and intercepts of the two groups are constrained by default in multiple group analyses, but current analyses revealed that this intercept was higher among African Americans.) Also, we released the correlation between the peer-reported and the counselor-reported items loading on the deviant peer clustering construct, which was significant only among African American youths. After releasing these two constraints, the Δ CFI between the two models was .011, suggesting the model is equivalent across the two ethnic groups.

Intervention status

There was no significant difference between the unconstrained model and the constrained model, as revealed by a Δ CFI of .008. This suggests that the overall model fits equally well for participants in the treatment group and in the control group.

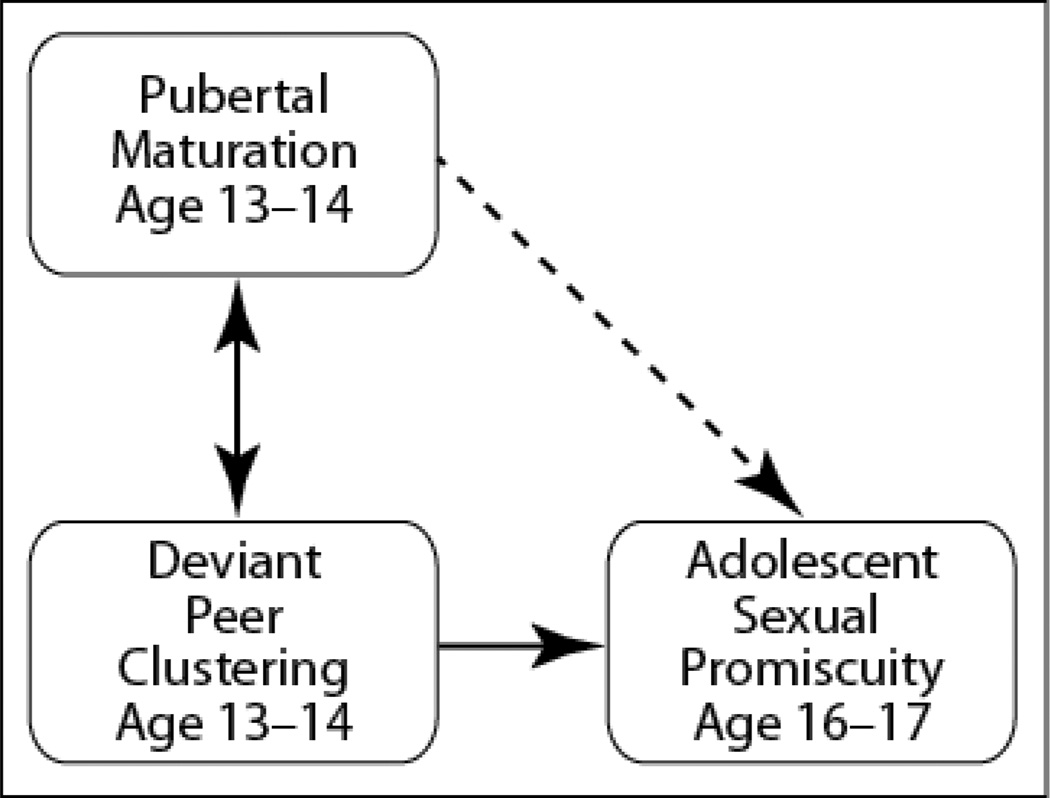

Pubertal Maturation and Sexual Promiscuity

Our measure of sexual maturation was available only for the at-risk participants (n = 405), a nonrandom subsample. Using structural equation modeling, we first examined whether pubertal maturation at age 13–14 predicted sexual promiscuity in middle adolescence, controlling for deviant peer clustering (see Figure 3). We first ran this model on the subsample of participants who provided valid data about pubertal status, and then on the overall sample, using FIML to account for missing data. In both analyses, the correlation between pubertal maturation and deviant peer clustering was nonsignificant. Deviant peer clustering was a robust predictor of sexual promiscuity (β = .33 for the subsample and .45 for the full sample, respectively; p < .001). Especially notable, we found that pubertal maturation was a relatively weak predictor of sexual activity 4 years later (β = .13, p < .05 for the subsample, and β = .12, p < .05 for the full sample). The multiple-group analyses revealed no difference in the strength of the relationship between pubertal maturation and future sexual promiscuity of boys and of girls, Δ CFI > .01.

Figure 3.

The specific effect of of early adolescent pubertal development on sexual promiscuity.

Even though preliminary analyses indicated that pubertal maturation was a rather weak competing predictor of adolescent sexual promiscuity when compared with deviant peer clustering, we added this variable to our final model (presented in Figure 2), and we used the full sample to verify whether any of the relationships among variables would change as a result of including this predictor. As expected, all path coefficients remained very similar to what we had found in the final model. The correlation between pubertal maturation and deviant peer clustering was still nonsignificant in this model (r = .09, p = .24), and the path from pubertal maturation to adolescence sexual promiscuity remained modest and statistically reliable (β = .13, p < .05).

Discussion

The results of these analyses suggest some merit in considering peers to be a core feature of a fast life history strategy during adolescence. Of particular importance to a life history perspective is the strong covariation between deviant peer clustering, sexual promiscuity, and early childbearing. When considering the evolutionary function of the developmental processes leading to problem behavior, the surge in adolescence is better understood. Pubertal maturation biologically drives increased interest in peer reinforcement, and this tendency is augmented for those youth in compromised social ecologies. In particular, youth with a history of antisocial behavior self-organize and enjoy a period of increased reward and peer social status during adolescence (Moffitt, 1993; Patterson, 1993), as well as sexual activity, and ultimately, more offspring during this developmental phase. Multiple forms of adolescent problem behavior share the common function of increasing the experience of high-intensity social reward, so it is easy to understand why peer contagion dynamics in group interventions and services might be difficult to contain.

This research reflects the first step toward empirically integrating peer relationships into a life history framework of adolescent problem behavior. It is worth noting the similarities in an evolutionary perspective and the learning-based social interactional perspective (Cairns, Gariépy, & Hood, 1990). In social interaction theory, dominant response patterns emerge through a process called selection by consequences (Patterson & Cobb, 1971, 1973), which is consonant with the concept of selective adaptation (Biglan, 2003). Thus, both models emphasize the function of behavior patterns in adaptation and maladaptation.

The core difference in the two perspectives is that the evolutionary account explains the social learning biases that co-occur with adolescent development, as well as epigenetic effects of developmental history on the formation of learning preferences. With respect to adolescent problem behavior, we propose that peer reinforcement (including status) becomes a learning bias, which would account for the relative power of peers to support problem behaviors in an unfolding developmental family dynamic called premature autonomy (Dishion et al., 2004). With puberty comes an array of physiological, hormonal, and neurocognitive changes that bias motivation and learning toward peer influence (Steinberg et al., 2006). Youths with a history of marginalization in the school setting and with parents self-organize into deviant peer clusters as automatically as hunters and gatherers foraged for food when hungry. Freeing oneself from the strings of parental control and engaging with peers in risky behaviors define the mesosystem of early autonomy (Dishion, Bullock, & Kiesner, 2008). A social context characterized by early autonomy is a prelude to opportunities for sexual interaction and a venue for violating community norms.

From an evolutionary perspective, sexual promiscuity and early-adulthood offspring define an early-reproduction sexual strategy (Belsky et al., 1991; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2008). In our study, when sexual promiscuity and early-adulthood offspring were presented as dependent variables, the importance of deviant peer clustering was supported in that a large percentage of the variance was accounted for by the peer-enhanced life history perspective in both constructs (for sexual promiscuity, R2 = .38, p < .001; for early adulthood progeny, R2 = .36, p < .001). This finding held when controlling for early pubertal maturation. The effects of attenuated family ties and peer marginalization on sexual promiscuity were entirely mediated through deviant peer clustering. Contrary to prediction, the effect of peer marginalization on adolescent problem behavior was only partially mediated by deviant peer clustering, also showing a direct effect. Given that teachers rated youths on peer marginalization in middle school as well as on problem behavior in high school, perhaps the youths’ problem behavior at both ages influenced teachers’ perceptions.

The core constructs in the model were measured intensively, and the effect coefficients were in the moderate (.35) to high (.5) range. More surprising, perhaps, is that the model summarized in Figure 2 was consistent when comparing males and females, as well as when comparing majority and minority adolescents, more specifically European American and African American youth. Although there were mean-level differences in some of the indicators of the constructs in the model, the data in general suggest that the process was quite similar for males and females and for majority and minority youth in this community sample. It is noteworthy that the effect of SES on deviant peer clustering and the number of offspring in early adulthood held when controlling for ethnicity, using a variety of strategies (e.g., majority versus minority; European American versus African American). This effect is consistent with life history theory (Belsky et al., 1991) and has been found in other large-scale, longitudinal research (e.g., Wu et al., 1996). It suggests that poverty, stigmatization, and disadvantage, in their various forms, have direct developmental effects on child and adolescent social and emotional development.

The conclusion—no differences relevant to sex in the life history perspective—is counterintuitive from sexual selection theory, which builds on several differences in respect to sex in mate selection and in aggression (see Archer, 2009). It is likely that the constructs tested in this particular model are simply not sensitive to individual difference factors during adolescence, such as attraction, romantic involvement, and other evolutionary dynamics that surely play out differently for adolescent males and adolescent females. In an earlier analysis predicting gang membership in early adolescence, the similarity of prediction was nearly identical for males and for females, except for the role of sociometric acceptance (Dishion et al., 2005). For males, being nominated by peers in school as “liked” as well as “rejected” combined to predict future gang membership. These data suggest that the process underlying male self-organization into deviant peer clusters is unique and associated with both status and rejection. As early as age 11, some males have high status in the deviant and nondeviant peer groups as a function of their problem behavior or perhaps physical attractiveness. It would be helpful if future research explored how sex differences play out in the early self-organization of deviant peer groups, as well as their ensuing interpersonal activities that culminate in sexual involvement.

The fast life history in general and many forms of adolescent problem behavior in particular meet the criteria of a psychological adaptation that may have reproductive consequences and thus evolutionary value (Schmitt & Pilcher, 2004). Theoretically, if a community structure evolves in such a way as to limit the potential mating opportunities of low-status but genetically viable individuals, then it is of value to the individual to reorganize socially so as to gain reproductive opportunities. Stultifying community contexts would limit the access to promising mates, and many genetically viable individuals would be unable to reproduce. Given that the structure of community groups is often defined by norms and rules, the self-organized adolescent groups would naturally be defined by norm-violating behavior and by defying or changing the rules of sexual engagement. If a process is to be of evolutionary value, it must generate outcomes that are directly linked to survival and reproduction. The link between deviant peer clustering, sexual promiscuity, and number of offspring is consistent with this evolutionary criterion.

In addition, selective adaptations must be consistent across cultures and history. As discussed previously, the tendency to violate community norms in adolescence is cross-cultural and historically robust (Schlegel & Barry, 1991). Given that most forms of aggression are socialized and reduced in early childhood (Tremblay, 2000), it is unlikely that the surge in various forms of adolescent problem behavior points simply to lack of socialization. It has been well established that adolescents who engage in high rates of various forms of problem behavior will desist contingent on skilled efforts from adults to increase support and monitoring on a daily level (Dishion, Nelson & Kavanagh, 2003; Forgatch & Patterson, 2010; Liddle, 1999). Even seriously problematic adolescents can reduce problem behavior without direct training, by responding to changes in the motivational structure of their daily lives (Chamberlain & Moore, 1998).

The life history framework suggests possible epigenetic effects on the neural behavioral system defined by sensitivity to reward. Future research may reveal that social marginalization heightens vulnerablity to peer influence, for example. Reward sensitivity is receiving increasing attention in the study of adolescent psychopathology in general (e.g., Fareri et al., 2008) and of risk-taking behavior in particular (Steinberg, 2007), including biosocial models of drug use and abuse (Kalivas & Volkow, 2005). Furthermore, experimental research in the laboratory reveals that experiences of social exclusion enhance motivation for future connection (Maner, DeWall, Baumeister, & Schaller, 2007). Imaging work by Eisenberger and colleagues reveals the effects on the amygdala of young adults’ acute sensitivity to social rejection (Eisenberger et al., 2003). Masten and colleagues have been studying the possibility of similar effects in adolescents (Masten, Eisenberger, Pfeifer, & Dapretto, 2010). The social augmentation hypothesis posits that peer exclusion leads to neuroanatomical shifts in reward sensitivity and that interpersonal influence is more easily achieved. The hypothesis could be using neuroimaging techniques that build on the Eisenberger paradigm.

Seen from an evolutionary perspective, the data in this report extend the model articulated and tested by Belsky and colleagues (Belsky et al., 1991; Belsky et al., 2010), because these data underscore the importance of the peer group in predicting early sexual activity and reproduction (see also James et al., this issue). The finding that pubertal development does not strongly predict sexual promiscuity after controlling for deviant peer involvement is consistent with that of other studies that measured these two constructs (Boislard & Poulin, 2010; Dishion & Medici Skaggs, 2001; French & Dishion, 2003). However, these studies as well as our own do not include strong measurement of adolescent puberty; relying exclusively on self-report assessment of maturation at age 12–13. Therefore, these models must be examined by measuring pubertal development of males and females as well as deviant peer clustering.

The peer-enhanced life history model has two sets of implications for interventions designed to prevent and treat problem behavior in adolescence. First and foremost, our data provide a deeper account of why young adolescents are so attentive to their proximal peer environment and perhaps why peer contagion processes are so salient (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). As stated in previous reports, interventions that identify and aggregate high-risk adolescents into preventive interventions may be well intentioned but are potentially harmful (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Dodge et al, 2006). Although many interventions that aggregate youth may not be associated with harm, it is likely that effect sizes are reduced, especially in early adolescence (Lipsey, 2006).

The second implication for intervention is that the public school context provides the majority of peer experiences identified in this study, and they affect long-term patterns of adolescent social and emotional development. Peer relationships can enhance academic progress (Véronneau, Vitaro, Brendgen, Dishion, & Tremblay, 2010) or contribute to a cycle of failure and amplify problem behavior, with considerable cost to the youth and the community (Biglan et al., 2004; Kiesner, Kerr, & Stattin, 2004). Public education systems would benefit from studies that focus on managing peer environments in schools, attend to issues of status and prestige in adolescence (Ellis et al., this issue), and promote inclusion and the integration of marginalized students in ways that reengage them in the learning environment. Perhaps interventions that emphasize group reinforcement and prosocial themes will more effectively reduce peer contagion dynamics (Crone & Horner, 2003; Embry, Flannery, Vazsonyi, Powell, & Atha, 1996; Poduska et al., 2008) because they promote peer interaction and reduce the need to create deviant subgroups. The question is not if such groups will form, but rather, how many youth will be engaged and what kinds of behaviors will be promoted.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants 07031 and 018760 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to the first author and by a Mosaic grant to the second author from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. Cheryl Mikkola is appreciated for providing editorial assistance. We are grateful to Drs. Bruce Ellis, Warren Holmes, Jeff Kiesner, Steve Suomi, and Mark Van Ryzin for review and comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

A warning was issued when running the multiple-group analysis to the effect that there was a linear dependency between deviant peer clustering and adolescent problem behavior among African Americans, thus suggesting that these two constructs are not as clearly distinct in this group as they are among European American adolescents. In line with our hypothesis, however, the estimated path from deviant peer clustering to sexual promiscuity remained significant for African American participants.

Contributor Information

Thomas J. Dishion, Arizona State University, Department of Psychology Child and Family Center, University of Oregon.

Thao Ha, Radboud University, Department of Development and Psychopathology.

Marie-Hélène Véronneau, Child and Family Center, University of Oregon; Université du Québec à Montréal, Department of Psychology.

References

- Achenbach TM. Developmental psychopathology. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Developmental psychopathology. In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, editors. Developmental psychology: An advanced textbook. 3rd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1992. pp. 62–675. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Does sexual selection explain human sex differences in aggression? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2009;32(3–4):249–311. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X09990951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Houts RM, Fearon RMP. Infant attachment security and the timing of puberty: Testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Psychological Science. 2010;21(9):1195–1201. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development. 1991;62:647–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Houts RM, Halpern-Felsher BL. The development of reproductive strategy in females: Early maternal harshness → earlier menarche → increased sexual risk taking. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(1):120–128. doi: 10.1037/a0015549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL. Peer rejection: Developmental processes and intervention strategies. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A. Selection by consequences: One unifying principle for a transdisciplinary science of prevention. Prevention Science. 2003;4(44):213–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1026064014562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Brennan P, Foster S, Holder H. Helping adolescents at risk: Prevention of multiple problem behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boislard-P M-A, Poulin F. Individual, familial and friends-related and contextual predictors of early sexual intercourse. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: 1. An evolutionary–developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development in Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Gariépy J-L, Hood KE. Development, microevolution, and social behavior. Psychological Review. 1990;97(1):49–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Stoolmiller M. Predicting the timing of first sexual intercourse for at-risk adolescent males. Child Development. 1996;67:344–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Moore KJ. Models of community treatment for serious offenders. In: Crane J, editor. Social programs that work. Princeton, NJ: Russell Sage; 1998. pp. 258–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Jr, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A, Dishion TJ, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone DA, Horner RH. Building positive behavior support systems in schools: Functional behavioral assessment. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent development and the regulation of behavior and emotion: Introduction to part VIII. In: Spear REDLP, editor. Adolescent brain development: Vulnerabilities and opportunities. New York, NY: Academy of Sciences; 2004. pp. 294–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal F. Morally evolved: Primate social instincts, human morality, and the rise and fall of “veneer theory”. In: de Waal F, Macedo S, Ober J, editors. Primates and philosophers: How morality evolved. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. pp. 2–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, Kiesner J. Vicissitudes of parenting adolescents: Daily variations in parental monitoring and the early emergence of drug use. In: Kerr M, Stattin H, Engels RCME, editors. What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2008. pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi D, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening with adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Medici Skaggs N. An ecological analysis of monthly “bursts” in early adolescent substance use. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behavior [Special issue] Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K. The Family Check-Up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring [Special issue] Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Yasui M. Predicting early adolescent gang involvement from middle school adaptation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):62–73. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 503–541. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner M. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA, Kavanagh K. Everyday parenting: A professional’s guide to building family management skills. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:189–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Véronneau M-H, Myers MW. Cascading peer dynamics underlying the progression from problem behavior to violence in early to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:603–619. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Dishion TJ, Lansford JE. Deviant peer influences in intervention and public policy for youth. Social Policy Report. 2006;20:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS. Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development. 2008;79(6):1907–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Malone PS, Lansford JE, Miller S, Pettit GS, Bates JE. A dynamic cascade model of the development of substance-use onset: Early peer relations problem factors. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74(3):51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT. Biological sensitivity to context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17(3):183–187. [Google Scholar]