Abstract

Cognitive functioning differs between males and females, likely in part related to genetic dimorphisms. An example of a common genetic variation reported to have sexually dimorphic effects on cognition and temperament in humans is the Val/Met polymorphism in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). We tested male and female wild-type mice (+/+) and their COMT knockout littermates (+/− and −/−) in the five-choice serial reaction time task (5CSRTT) to investigate the effects of sex, COMT genotype, and their interactions with environmental manipulations of cognitive functions such as attention, impulsivity, compulsivity, motivation, and rule-reversal learning. No sex- or COMT-dependent differences were present in the basic acquisition of the five-choice serial reaction time task. In contrast, specific environmental manipulations revealed a variety of sex- and COMT-dependent effects. Following an experimental change to trigger impulsive responding, the sexes showed similar increases in impulsiveness, but males eventually habituated whereas females did not. Moreover, COMT knockout mice were more impulsive compared with wild-type littermates. Manipulations involving mild stress adversely affected cognitive performance in males, and particularly COMT knockout males, but not in females. In contrast, following amphetamine treatment, subtle sex by genotype and sex by treatment interactions emerged primarily limited to compulsive behavior. After repeated testing, female mice showed improved performance, working harder and eventually outperforming males. Finally, removing the food-restriction condition enhanced sex and COMT differences, revealing that overall, females outperform males and COMT knockout males outperform their wild-type littermates. These findings illuminate complex sex- and COMT-related effects and their interactions with environmental factors to influence specific executive cognitive domains.

Keywords: gender, operant behavior, food ad libitum, psychiatric disorders

Investigation of the interplay of sex, gene modifications, and environmental factors may provide insight into vulnerabilities that give rise to neurobehavioral disorders. The catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene constitutes an appealing candidate in the study of gene–sex–environment interactions, for a number of reasons, including that COMT modulates dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (1–4); PFC function varies between the sexes (5, 6); COMT exhibits sexually dimorphic associations in humans (7); and COMT is regulated by estrogen (8). Moreover, PFC dopamine transmission is involved in multiple spheres of human behavior, thought, and emotion (9). Consistent with this, COMT genetic variation leads to pleiotropic behavioral effects in humans as well as in mice (10–16). In particular, remarkable similarities have been demonstrated between mice and humans with respect to the effects of COMT genetic variations on aspects of cognition, emotional arousal, pain sensitivity, and amphetamine responsivity (11–18).

A number of cognitive disturbances and psychiatric abnormalities such as schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), drug addiction, and autism present different behavioral characteristics depending on the sex of the subject (19–23). Moreover, a growing body of evidence suggests that COMT-related enzymatic activity and its relationship to several of these clinical phenotypes exhibit sexual dimorphism (SI Appendix, Table S1). For instance, association studies of ADHD and COMT alleles suggest that attentional disorders may be modulated by a sex X COMT interaction (11, 24, 25). Moreover, whereas genetic modifications that lead to reduced COMT activity have been linked to increased risk of obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD) exclusively in males, they have been associated with nicotine dependence, panic, and anxiety-related disorders only in females (7, 26, 27). COMT variation also shows dramatic interactions with sex in aspects of human personality (28).

The contribution of COMT X sex interactions to increased individual vulnerability to psychopathology is evidently neither simple nor clear-cut. In the present study, our goal was to investigate sex and COMT effects in several different cognitive domains and examine how their interactions are regulated by environmental changes. To this end, we tested the influence of various environmental conditions on the cognitive performance of COMT genetically modified male and female mice in the five-choice serial reaction time task (5CSRTT). This paradigm requires subjects to detect brief flashes of light presented in a pseudorandom order in one of five spatial locations over a large number of trials. In particular, the 5CSRTT allows separate assessment of attention, impulse control, perseverative, and reactivity-related functions in rodents (29). The current investigation illustrates the impact of sex, COMT genetic reduction, environmental influence, and their respective interactions on the neurocognitive modulation of attention, impulsivity, stress reactivity, compulsivity, flexibility, and motivation.

Results

No Significant Sex or COMT Genotype Effects on the Basic Acquisition of the 5CSRTT.

Female and male COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice readily acquired this task and overall took an average of 39 d to reach the final stage 7. During the training phases, no sex or genotype differences or interactions were apparent in any of the parameters measured (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

During the 100-trial stabilization and 2-wk baseline periods, no major sex or genotype differences or interactions were evident in most of the parameters measured (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S4). During the baseline period, only one sex effect, but no interactions, was present: latency to correct choice (F1,47 = 4.71; P < 0.05). Female mice were faster than their male counterparts to make a correct response (P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Trait Impulsivity Is More Enduring in Females and Is Higher in COMT Knockout Mice.

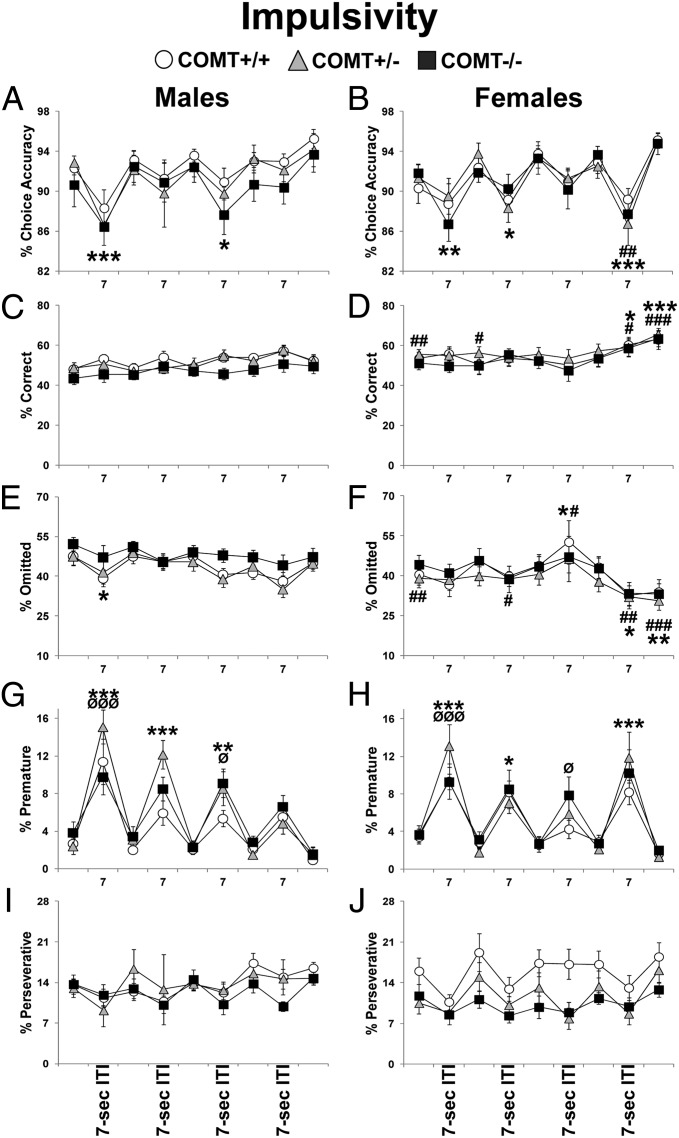

Trait impulsivity in rats is revealed in the 5CSRTT when intertrial intervals (ITIs) are increased from 5 to 7 s (30). Here we demonstrated that, as in rats, mice are sensitive to this manipulation. Indeed, premature responses (an index of impulsivity) showed an effect of testing day (F8,376 = 59.80; P < 0.0001), a sex X day interaction (F8,376 = 4.06; P < 0.0005), and a COMT X day interaction (F16,376 = 1.92; P < 0.05). A robust increase in premature responses was present in the days following the shift to 7-s ITIs (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1 G and H). Male but not female mice exhibited a habituation-like process in that the effect of the 7-s ITI gradually decreased over sessions in males only (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1 G and H). Finally, post hoc analysis of the genotype X day interaction effect revealed that +/− and −/− mice made more premature responses compared with +/+ littermates in the days in which the ITI was increased from 5 to 7 s (P < 0.05; Fig. 1 G and H).

Fig. 1.

Performance displayed by COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice during 4-wk impulsivity screening at different ITI delays (5-s ITIs: Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays; 7-s ITIs: Wednesdays). For clarity, data from consecutive days with the normal 5-s ITIs were averaged. Choice accuracy in males (A) and females (B). Correct responses in males (C) and females (D). Trial omissions in males (E) and females (F). Premature responses in males (G) and females (H). Perseverative responses in males (I) and females (J). n = 7/11 per group throughout the figures. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, and ***P < 0.0005 vs. 5-s ITI performance; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.005, and ###P < 0.0005 vs. same time point in males. ØP < 0.05 and ØØØP < 0.0005 vs. +/+ same-sex littermates. Values represent mean ± SEM in all figures.

Increasing ITI duration also affected choice accuracy (an index of attention). Choice accuracy showed a testing-day effect (F8,376 = 18.38; P < 0.0001) and a sex X day interaction (F8,376 = 2.80; P < 0.005). In particular, whereas in males, accuracy levels decreased during the first and third ITI change presentation (P < 0.05; Fig. 1A), they decreased in all but the third ITI change session in females (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). Moreover, female mice had decreased accuracy levels relative to male counterparts during the fourth ITI change (P < 0.005; Fig. 1 A and B).

Similarly, for incorrect responses, there was a testing-day effect (F8,376 = 21.24; P < 0.0001) and a sex X day interaction effect (F8,376 = 3.65; P < 0.0005). Specifically, incorrect responses increased during the days of the 7-s ITI change presentation in both males and females (P < 0.05). However, females made more incorrect responses compared with their male counterparts during the day of the last 5- to 7-s ITI shift (P < 0.0001; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The 5- to 7-s ITI shift did not impact other parameters such as correct responses, omissions, perseverative responses, latencies to correct and reward responses, time out, and total responses (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Females Learn to Outperform Males.

Starting from the impulsivity screening phase, marked sex effects were observed to be independent of manipulations and genotype. Indeed, during the 4 wk of the impulsivity screening, correct responses showed a sex effect (F1,48 = 4.53; P < 0.05) and a sex X day interaction (F8,376 = 4.58; P < 0.0001). Relative to males, females demonstrated a higher percentage of correct responses (P < 0.05; Fig. 1 C and D). This was due to improvement in female performance around the 2 last days of testing in this phase (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D). Similarly, for omissions, a sex X day interaction (F8,376 = 7.72; P < 0.0001) revealed that female mice had fewer omissions compared with males (P < 0.05; Fig. 1 E and F). In particular, this was again due to improved performance of females on the 2 last days of this phase of the experiment (P < 0.05; Fig. 1F). A sex effect was also present for the latency to produce correct responses (F1,48 = 4.17; P < 0.05) and for the total number of responses (F1,48 = 5.27; P < 0.05). Females made correct responses faster (P < 0.05) and displayed more total responding (P < 0.05), again due to a progressive improvement of their performance over time (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These same sex-dependent differences endured and strengthened through the rest of the test (Figs. 2–4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S5–S14). COMT genotype did not influence these effects.

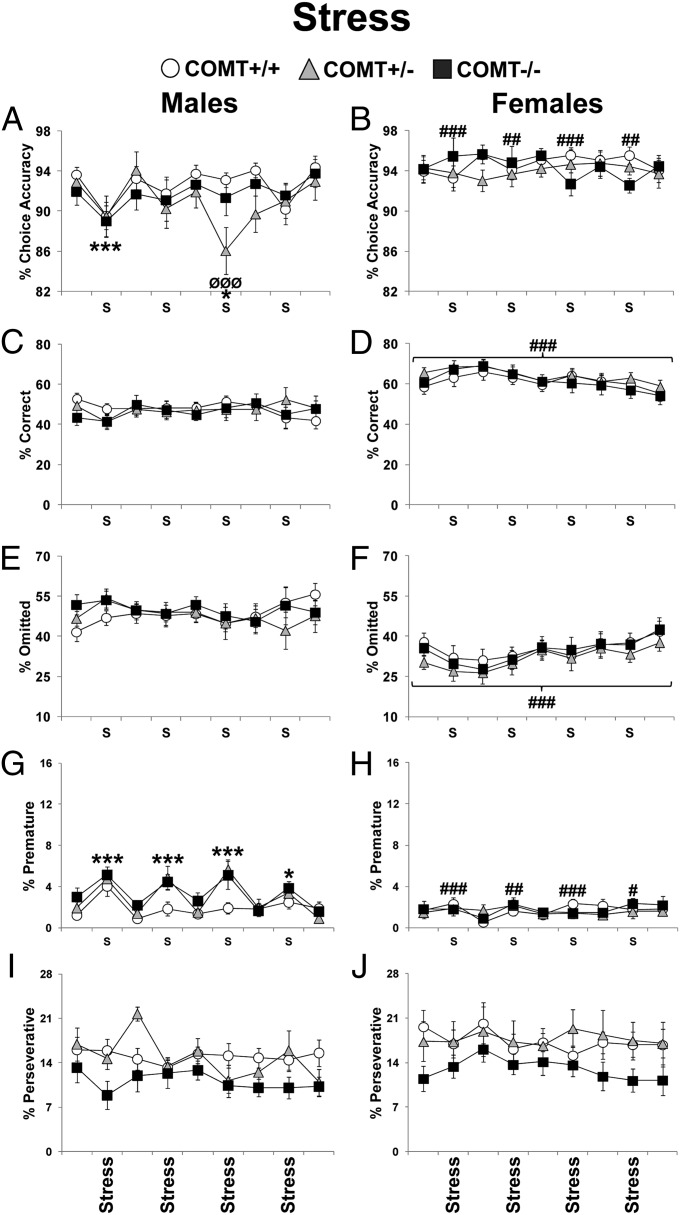

Fig. 2.

Performance displayed by COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice during 2 wk of pretest exposure to a mild stressor every other day (nonstress days: Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays; stress days: Tuesdays and Thursdays). For clarity purposes, data from a consecutive Friday and Monday were averaged. Choice accuracy displayed by males (A) and females (B). Correct responses in males (C) and females (D). Trial omissions in males (E) and females (F). Premature responses in males (G) and females (H). Perseverative responses in males (I) and females (J). *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.0005 vs. performance on days with no stress; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.005, and ###P < 0.0005 vs. same time point in males. ØØØP < 0.0005 vs. +/+ same-sex littermates.

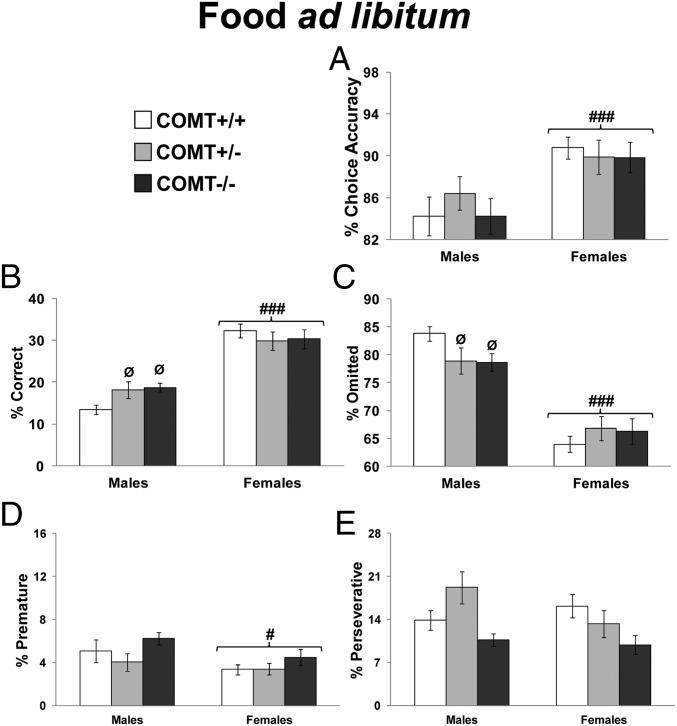

Fig. 4.

Performance displayed by COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice with food ad libitum. As no time-dependent effect was present, data are reported as the average of the 10 d of testing under this condition. (A) Choice accuracy in males and females. (B) Correct responses in males and females. (C) Trial omissions in males and females. (D) Premature responses in males and females. (E) Perseverative responses in males and females. #P < 0.05 and ###P < 0.0005 vs. males. ØP < 0.05 vs. +/+ same-sex littermates.

Males, Particularly COMT Knockout Males, Are More Sensitive to a Mild Stressor.

COMT genetic modification modulates reactivity to stress (15). We therefore investigated whether stress interacts with sex and/or COMT in the modulation of 5CSRTT performances. Mice were placed 2 d/wk in a clean new cage in light (∼800 lux) before the test (testing always took place during the dark cycle). The only parameters that appeared to be affected by this mild stress manipulation were accuracy and premature responding.

Choice accuracy showed a sex effect (F1,48 = 10.81; P < 0.005), a testing-day effect (F8,384 = 3.70; P < 0.0005), a sex X day interaction (F8,384 = 2.77; P < 0.006), and a sex X genotype X day interaction (F16,384 = 1.91; P < 0.02). In particular, stress-induced decreased accuracy was observed only in males (P < 0.05; Fig. 2A) but not in females (P > 0.7; Fig. 2B). Moreover, males showed lower levels of accuracy than females in the days of exposure to the stress (P < 0.005; Fig. 2 A and B). Finally, the COMT+/− males showed a more robust decrease in accuracy compared with their +/+ littermates during the third time of stress manipulation (P < 0.0005; Fig. 2A).

Premature responses showed a sex effect (F1,48 = 10.84; P < 0.005), a strong testing-day effect (F8,384 = 9.50; P < 0.0001), and a sex X day interaction (F8,384 = 5.43; P < 0.0001). Males (P < 0.05), but not females (P > 0.80), showed a significant increase in premature responses following stress manipulation (Fig. 2 G and H). Moreover, males displayed higher levels of premature responses than females only during days of stress exposure (P < 0.05; Fig. 2 G and H). Even though there was no significant sex X genotype X day interaction effect (F16,384 = 1.30; P = 0.19), a post hoc analysis of this interaction revealed that COMT+/− and −/− males made more premature responses than +/+ littermates following the second and third stress exposure (P < 0.05; Fig. 2G). This mild stress manipulation did not consistently impact other parameters (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

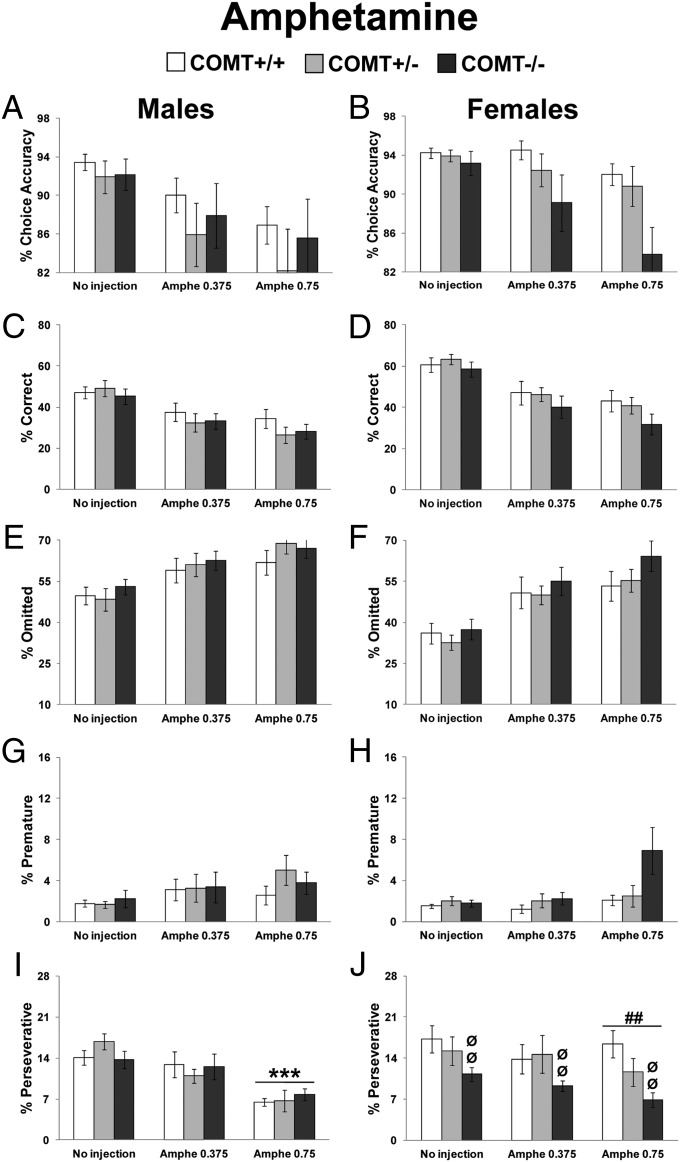

Amphetamine Effects on the 5CSRTT.

Amphetamine may interact with COMT to affect cognition in both humans and mice (15, 17). We then injected male and female COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice with amphetamine (0.75 or 0.375 mg/kg, i.p.) on days 2 and 4 of 2 consecutive weeks.

Amphetamine produced a treatment effect in choice accuracy (F2,141 = 10.59; P < 0.0001), correct responses (F2,141 = 34.63; P < 0.0001), omissions (F2,141 = 31.52; P < 0.0001), premature responses (F2,141 = 6.13; P < 0.005), latency to correct responses (F2,141 = 14.39; P < 0.0001), and latency to reward (F2,141 = 4.33; P < 0.05). Amphetamine impaired 5CSRTT performance, as it dose-dependently reduced choice accuracy (P < 0.05; Fig. 3 A and B), reduced correct responses (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3 C and D), increased omissions (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3 E and F), increased premature responses (P < 0.005; Fig. 3 G and H), increased the latency to produce correct responses (P < 0.0001), and increased the latency to retrieve the food (P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Perseverative responses showed an amphetamine-treatment effect (F2,141 = 11.89; P < 0.0001) and a sex X treatment interaction (F2,141 = 2.93; P = 0.05). This interaction reflected that amphetamine reduced perseverative responses in males (P < 0.0001) but not in females (P > 0.23) (Fig. 3 I and J). No effect of amphetamine was present for incorrect and time-out responses (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Thus, systemic administration of amphetamine in mice increased 5CSRTT premature responding and reduced response vigor as similarly found with rats (29).

Fig. 3.

Performance displayed by COMT+/+, +/−, and −/− mice during amphetamine manipulation (no injection: Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays; 0.75 or 0.375 mg⋅kg−1⋅10 mL−1 i.p. amphetamine injection immediately before the test: Tuesdays and Thursdays). Data are reported as the average from the same injection conditions. Choice accuracy in males (A) and females (B). Correct responses in males (C) and females (D). Trial omissions in males (E) and females (F). Premature responses in males (G) and females (H). Perseverative responses in males (I) and females (J). ***P < 0.0005 vs. no injection; ##P < 0.005 vs. same injection condition in males. ØØP < 0.005 vs. +/+ same-sex littermates.

Motivational Shift Reveals Sex- and COMT-Dependent Effects.

To examine cognitive differences between sexes and COMT genotypes under more natural conditions, we tested COMT knockout male and female mice in the 5CSRTT during ad libitum access to food. This manipulation eliminates the stress and metabolic components linked to the food-restriction procedures and might increase the sensitivity of operant tasks (31).

We first analyzed the parameters of the 5CSRTT, comparing the performance of the experimental groups before (i.e., during food restriction) and during the food ad libitum manipulation. This revealed that food ad libitum had a comparatively negative impact on performance, with no interactions with sex and COMT genotype: correct responses decreased (F1,48 = 377.47; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4B vs. Fig. 3 C and D), omissions increased (F1,48 = 397.70; P < 0.0001; Fig. 4C vs. Fig. 3 E and F), and reward latency increased (F1,48 = 9.98; P < 0.005; SI Appendix, Fig. S8 vs. Fig. S7). This is consistent within an overall decrease in motivation, as would be expected. In contrast, this manipulation interacted with sex specifically for attentional indexes, as it decreased accuracy more in males than in females (F1,48 = 9.85; P < 0.003; Fig. 4A vs. Fig. 3 A and B).

Then, analyses of each single parameter revealed that the food ad libitum manipulation brought out effects that were not present during food-restriction conditions. Specifically, compared with males, females were more accurate (P < 0.0008; Fig. 4A) and made fewer premature responses (F1,48 = 4.85; P < 0.05; Fig. 4D), broadening the indexes showing better performance in females. Indeed, consistent with earlier stages with food restriction, other sex effects revealed that, compared with males, females of all genotypes made more correct responses (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4B), made fewer omissions (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4C), made correct responses faster (P < 0.0001; SI Appendix, Fig. S8), and displayed more total responding (P < 0.0001; SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Previously absent sex X genotype interactions appeared for correct choices (F2,48 = 3.31; P < 0.05), omissions (F2,48 = 3.09; P = 0.05), and perseverative responses (F2,48 = 2.52; P = 0.09). Specifically, relative to their +/+ littermates, whereas COMT+/− and −/− males showed increased correct choices (P < 0.05; Fig. 4B) and decreased omissions (P < 0.08; Fig. 4C), no COMT-dependent differences were present in females (P > 0.40; Fig. 4 B and C). Moreover, COMT−/− mice made fewer perseverative responses compared with +/+ (P < 0.05; Fig. 4E). These results indicate that under food ad libitum conditions, reduced COMT activity enhanced 5CSRTT performance in males but not in females.

No Sex- or COMT-Dependent Differences During Rule-Reversal Learning.

Before testing the ability to revert an acquired rule (i.e., shifting the correct response from the illuminated to an unlit hole), we returned our mice to their baseline food-restriction performance. After weight restriction was reintroduced, males took about 1 wk to improve their performance back to baseline levels, whereas, in contrast, females displayed a complete behavioral recovery from the first day of the restabilization period (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). All mice, irrespective of sex and COMT genotype, were able to reverse the prior rule, suggesting that neither sex nor COMT impacts reversal learning in this paradigm (SI Appendix, Figs. S11 and S12).

Food ad Libitum Conditions Consistently Enhance COMT- and Sex-Dependent Differences.

We tested once again whether behavioral performance was modulated by food ad libitum conditions, this time in the context of the acquired reverted rule (i.e., correct responses in an unlit hole). As previously observed (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8), testing mice under food ad libitum conditions revealed sex- and COMT-dependent differences that were not evident under food-restricted conditions (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14). These results strengthen the conclusions that, under food ad libitum conditions, reduced COMT is advantageous in males but not in females and that this manipulation possesses the sensitivity to reveal sex- and genotype-dependent differences.

Discussion

The present results demonstrate that mice, and COMT knockout mice in particular, are an informative tool for investigating the influence of sex X gene X environment interactions on cognitive abilities implicated in a variety of human cognitive disorders. Moreover, the 5CSRTT and the environmental manipulations tested proved to be a sensitive tool for detecting these sex- and gene-dependent vulnerabilities. In particular, sex and COMT genotype differences that emerged during environmental manipulations were not generally present during the initial acquisition and execution of the task, highlighting the importance of environmental changes in triggering sex- or gene-dependent vulnerabilities.

No Major Sex or COMT Differences in Training and Stabilization.

Neither sex nor COMT genotype exerted a robust effect on either acquisition or baseline performance in the various cognitive functions assessed by the 5CSRTT. Thus, the sex and genotype differences found in the successive manipulations are likely real sex and/or genotype vulnerabilities dependent on environmental changes. Our previous work uncovered a strong effect of COMT genotype on working memory in males (15). However, in this study, COMT reductions did not have a robust effect on either acquisition or performance of the standard 5CSRTT. This suggests that COMT has a relatively more specific influence on the modulation of working memory than on sustained attention, where its role appears to be more subtle. This is analogous to human studies showing inconsistent effects of COMT genetic functional variance on measures of attention using the Continuous Performance Test (14). The 5CSRTT is in fact modeled after this human test. Previous studies in rats reported that sustained attention in the 5CSRTT depends on the PFC and might be modulated by D1 dopamine receptor agents (32, 33). In particular, infusion of a D1 agonist (SKF38393) into the medial PFC enhanced the performance of rats with low (<75%) but not high (>75%) baseline levels of accuracy (32). Thus, given the relevance of COMT knockout mice as a model of increased dopamine flux in the PFC, and the high levels of accuracy reached by most of our mice (>80%), the lack of impact of COMT genetic disruption on baseline 5CSRTT performance is probably not surprising. In agreement, only limited evidence has shown an effect of COMT polymorphisms on attentional processes in humans (11). In particular, these studies have reported that COMT Met subjects, who are a human analog to our knockout mice, perform better in parameters of lapses of attention, conflict monitoring, and distractibility (34–36). Thus, either COMT is not strongly implicated in the sustained attention abilities assessed by the standard 5CSRTT or “ceiling effects” made it difficult to detect the expected improvements.

More Enduring Impulsive Behavior in Females and Higher Trait Impulsivity in COMT Knockout Mice.

In contrast to the lack of marked effects of sex and COMT genotypes on baseline cognitive performance in the 5CSRTT, sex and COMT did impact environmental modulation of performance. We investigated trait impulsivity by adopting a test manipulation previously used in rats (30). Similar to rats, in both male and female mice, increasing the intertrial interval from 5 to 7 s resulted in an increase in premature responding with no significant effects on other measures. However, whereas males seem to learn a “strategy” to cope with the increased demands of response inhibition during the increased delay, whereby the intensity of their impulsive responses diminished with repeated 5- to 7-s ITI shift exposure, this adjustment was absent in females. In agreement, female mice and rats have previously demonstrated higher impulsivity than males in delay-discounting paradigms (37, 38). Premature responses are thought to reflect a failure of inhibitory response control, appearing when preparatory response mechanisms are disrupted (39). Thus, our results indicate that this manipulation can be successfully applied to genetically modified mice, and suggest that male mice might be more resistant to repeated impulsivity screening than females. We also found increased premature responding in COMT knockouts relative to wild types during the 5- to 7-s ITI shift. Furthermore, during exposure to a mild stress, we found again increased impulsive behavior in COMT knockout mice, but now only in males. This suggests that a relative COMT decrease results in increased trait impulsivity measured by response inhibition and, that under conditions of stress, this effect is exaggerated in males. It is interesting to note that response-inhibition deficits are present in OCD (40), and that the COMT Met polymorphism (i.e., reduced COMT activity) has been consistently associated with increased risk for OCD in men but not in women (26, 27). Similarly, considering that impulsivity is an important factor in suicidal behavior (41), the COMT Met allele has been reported to be a risk factor for suicide in men but not in women (42, 43). The COMT Met allele has also been associated with increased aggressive behavior in men (44), which may be another reflection of impulsivity (40, 41). In agreement with these human studies and paralleling our present data, male mice with reduced COMT show increased aggressive behavior (1). Finally, these results are at least theoretically consistent with the finding that the COMT Met variant has been associated with ADHD in males but not in females (24, 45), another condition characterized by impulsivity. Thus, inappropriate responsivity to stressful events dependent on reduced COMT may be related to the expression of psychiatric disorders related to impulse control, particularly in males.

Mild Stress Impairs Attention and Increases Impulsivity in Males, and Particularly in COMT Knockout Males.

Males in general and COMT+/− and −/− males in particular were more sensitive than females to the disruptive effects of a mild stressor on attentive and impulsive abilities. Several lines of evidence suggest that there are sex differences in biologic and behavioral responses to stress, and sex-based differences are common in some psychiatric illnesses (46). The 5CSRTT has been used as a preclinical rodent test to study ADHD (29). It is thus interesting to note that our results mirror the finding that ADHD symptoms are often worsened by stress, that boys are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls, and that girls with ADHD exhibit lower ratings on inattention and impulsivity relative to boys (22, 46). Here we demonstrate that males are more sensitive to the negative effects of physical stress or that the stressor we picked is perceived as more stressful to males in measures of attention and impulsivity. We cannot conclude, however, that this effect translates to stress in general, because females might be more vulnerable to other stressors (e.g., social stressors).

Food ad Libitum Conditions Show Greater Sensitivity in Detecting Sex- and COMT-Dependent Differences.

Food restriction is a stressful condition that increases reward seeking/motivation, and the food ad libitum condition may serve as a more sensitive method of detecting environment- and genetic-dependent differences (31, 47). In support of this, testing under food ad libitum conditions revealed sex- and COMT-dependent effects that were not evident under food restriction. Specifically, this manipulation proved to be more sensitive in detecting females’ better performance compared with males, as their relatively superior accuracy was not evident in manipulations with food restriction. Choice accuracy is an index of attention thought to bypass nonspecific influences such as motivational factors (29). Thus, we can conclude that food ad libitum conditions are more sensitive in detecting sex-dependent differences. Moreover, these results strengthened evidence that compared with males, females work harder and more efficiently in the 5CSRTT.

Male mice with reduced COMT outperformed their wild-type littermates during the food ad libitum phase, showing increased correct choices and decreased omissions. This is in agreement with findings in humans and mice showing that reduced COMT per se is advantageous for cognitive performance (11, 13, 15). Interestingly, these COMT-dependent effects were not present in females. This is further evidence that the effects of COMT genotype on cognitive function depend on sex, the demands of a specific task, and environmental conditions.

The manipulation of satiety (i.e., devaluation) has been used by others to study possible involvement of habitual-like processes (48, 49). Our paradigm was not designed to study habitual behaviors. However, because the reduction of food value immediately reduced performance despite the mice having arrived at this stage after extensive training, the actions measured by the 5CSRTT seem more goal directed than habitual. Moreover, possible habitual processes might be sex and COMT independent, as all groups of mice similarly reduced their motor responses following this manipulation.

In conclusion, the present results add to a growing body of research showing complex sex–gene–environment interactions in various aspects of cognition, behavior, and possibly vulnerability to psychiatric disorders. In particular, our data highlight that effects of genotype are rarely as simple as painted by studying only one sex under a single condition. COMT genetically modified mice, because they exhibit alterations in cortical circuits important for processing of cognition and emotion, illustrate these principles and further suggest that inconsistencies in prior clinical associations may be confounded by such sex and environmental factors (SI Appendix, Table S1 illustrates COMT-dependent sexually dimorphic effects in humans contrasted with mice studies). These sex–genotype–environment interactions may be reliably studied in clinically relevant mouse models and may have important implications for the development of future therapeutic strategies.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were approved by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institutes of Health guidelines (50). Three- to 6-mo-old COMT null mutant mice (1, 15) (COMT−/−) and their heterozygous (COMT+/−) and wild-type (COMT+/+) littermates were used. Mice were trained in operant conditioning boxes as previously described (29). For detailed descriptions of the procedures and parameters used, see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. The overall time line of the procedural manipulations is reported in SI Appendix, Fig. S15. Three-way ANOVAs with genotype (+/+, +/−, or −/−) and sex (males or females) as between-subject factors and repeated measures as within-subject factors were used for the training, stabilization, baseline, impulsivity screening, stressor, before/during food ad libitum, and reversal phases. Three-way ANOVAs with genotype, sex, and amphetamine treatment (no injection, amphe0.375, or amphe0.75) as independent variables were used for the amphetamine-treatment phase. Two-way ANOVAs with genotype and sex as independent variables were used for the food ad libitum phases. For clarity, we report in the main text only the significant main effects and interactions. Complete and detailed statistical analyses are reported in SI Appendix. For clarity, results in the figures are represented separately but paired by sex and using the same scales for each parameter. The Tukey honest significance test (HSD) for unequal N post hoc testing was used for individual group comparisons. The accepted value for significance was P ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. Lu for material support; Q. Tian and T. Telahun for technical assistance; and Drs. M. Karayiorgou and J. A. Gogos for donating the COMT−/− mice breeders. This research was supported by the Intramural Program of the NIMH (DRW laboratory). L.E.’s appointment and operant boxes were supported by an NIMH Julius Axelrod Memorial Fellowship Training Award (to F.P.). F.P. was also supported by the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia and by the Marie Curie Seventh Framework Programme Reintegration Grant 268247.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1214397109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gogos JA, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(17):9991–9996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Käenmäki M, et al. Quantitative role of COMT in dopamine clearance in the prefrontal cortex of freely moving mice. J Neurochem. 2010;114(6):1745–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tunbridge EM, Bannerman DM, Sharp T, Harrison PJ. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition improves set-shifting performance and elevates stimulated dopamine release in the rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24(23):5331–5335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yavich L, Forsberg MM, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA, Männistö PT. Site-specific role of catechol-O-methyltransferase in dopamine overflow within prefrontal cortex and dorsal striatum. J Neurosci. 2007;27(38):10196–10209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0665-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staiti AM, et al. A microdialysis study of the medial prefrontal cortex of adolescent and adult rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(3):544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smaers JB, Mulvaney PI, Soligo C, Zilles K, Amunts K. Sexual dimorphism and laterality in the evolution of the primate prefrontal cortex. Brain Behav Evol. 2012;79(3):205–212. doi: 10.1159/000336115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison PJ, Tunbridge EM. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): A gene contributing to sex differences in brain function, and to sexual dimorphism in the predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(13):3037–3045. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohn CK, Axelrod J. The effect of estradiol on catechol-O-methyltransferase activity in rat liver. Life Sci I. 1971;10(23):1351–1354. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(71)90335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman-Rakic PS. The cortical dopamine system: Role in memory and cognition. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:707–711. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60846-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Tuathaigh CM, et al. Genetic vs. pharmacological inactivation of COMT influences cannabinoid-induced expression of schizophrenia-related phenotypes. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(9):1331–1342. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheggia D, Sannino S, Scattoni ML, Papaleo F. COMT as a drug target for cognitive functions and dysfunctions. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;11(3):209–221. doi: 10.2174/187152712800672481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz A, Smolka MN. The effects of catechol O-methyltransferase genotype on brain activation elicited by affective stimuli and cognitive tasks. Rev Neurosci. 2006;17(3):359–367. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan MF, et al. Effect of COMT Val108/158 Met genotype on frontal lobe function and risk for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(12):6917–6922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111134598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg TE, et al. Executive subprocesses in working memory: Relationship to catechol-O-methyltransferase Val158Met genotype and schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):889–896. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papaleo F, et al. Genetic dissection of the role of catechol-O-methyltransferase in cognition and stress reactivity in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(35):8709–8723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2077-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segall SK, et al. Comt1 genotype and expression predicts anxiety and nociceptive sensitivity in inbred strains of mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2010;9(8):933–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattay VS, et al. Catechol O-methyltransferase val158-met genotype and individual variation in the brain response to amphetamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):6186–6191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931309100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nackley AG, et al. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science. 2006;314(5807):1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1131262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andreano JM, Cahill L. Sex influences on the neurobiology of learning and memory. Learn Mem. 2009;16(4):248–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.918309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knickmeyer RC, Baron-Cohen S. Fetal testosterone and sex differences in typical social development and in autism. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(10):825–845. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210101601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aleman A, Kahn RS, Selten JP. Sex differences in the risk of schizophrenia: Evidence from meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):565–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gershon J. A meta-analytic review of gender differences in ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2002;5(3):143–154. doi: 10.1177/108705470200500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papaleo F, Contarino A. Gender- and morphine dose-linked expression of spontaneous somatic opiate withdrawal in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2006;170(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Biederman J, et al. Sexually dimorphic effects of four genes (COMT, SLC6A2, MAOA, SLC6A4) in genetic associations of ADHD: A preliminary study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(8):1511–1518. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian Q, et al. Family-based and case-control association studies of catechol-O-methyltransferase in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder suggest genetic sexual dimorphism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003;118B(1):103–109. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor S. Molecular genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comprehensive meta-analysis of genetic association studies. Mol Psychiatry. June 5, 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pooley EC, Fineberg N, Harrison PJ. The met(158) allele of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder in men: Case-control study and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(6):556–561. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, et al. Sex modulates the associations between the COMT gene and personality traits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(8):1593–1598. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robbins TW. The 5-choice serial reaction time task: Behavioural pharmacology and functional neurochemistry. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163(3-4):362–380. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalley JW, et al. Nucleus accumbens D2/3 receptors predict trait impulsivity and cocaine reinforcement. Science. 2007;315(5816):1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.1137073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papaleo F, Kieffer BL, Tabarin A, Contarino A. Decreased motivation to eat in mu-opioid receptor-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(11):3398–3405. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granon S, et al. Enhanced and impaired attentional performance after infusion of D1 dopaminergic receptor agents into rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20(3):1208–1215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. The cerebral cortex of the rat and visual attentional function: Dissociable effects of mediofrontal, cingulate, anterior dorsolateral, and parietal cortex lesions on a five-choice serial reaction time task. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6(3):470–481. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasi G, et al. Effect of catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met genotype on attentional control. J Neurosci. 2005;25(20):5038–5045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0476-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamidovic A, Dlugos A, Palmer AA, de Wit H. Catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met genotype modulates sustained attention in both the drug-free state and in response to amphetamine. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20(3):85–92. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833a1f3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmboe K, et al. Polymorphisms in dopamine system genes are associated with individual differences in attention in infancy. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(2):404–416. doi: 10.1037/a0018180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koot S, van den Bos R, Adriani W, Laviola G. Gender differences in delay-discounting under mild food restriction. Behav Brain Res. 2009;200(1):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perry JL, Nelson SE, Anderson MM, Morgan AD, Carroll ME. Impulsivity (delay discounting) for food and cocaine in male and female rats selectively bred for high and low saccharin intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(4):822–837. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Dissociable contributions of the orbitofrontal and infralimbic cortex to pavlovian autoshaping and discrimination reversal learning: Further evidence for the functional heterogeneity of the rodent frontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23(25):8771–8780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychiatry of impulsivity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):255–261. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280ba4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swann AC. Impulsivity in mania. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(6):481–487. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nolan KA, et al. Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia is related to COMT polymorphism. Psychiatr Genet. 2000;10(3):117–124. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200010030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ono H, Shirakawa O, Nushida H, Ueno Y, Maeda K. Association between catechol-O-methyltransferase functional polymorphism and male suicide completers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(7):1374–1377. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Volavka J, Bilder R, Nolan K. Catecholamines and aggression: The role of COMT and MAO polymorphisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1036:393–398. doi: 10.1196/annals.1330.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheuk DK, Wong V. Meta-analysis of association between a catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Genet. 2006;36(5):651–659. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein LC, Corwin EJ. Seeing the unexpected: How sex differences in stress responses may provide a new perspective on the manifestation of psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4(6):441–448. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0072-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papaleo F, Weinberger DR, Chen J. Animal models of genetic effects on cognition. In: Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR, editors. The Genetics of Cognitive Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 51–94. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilario MR, Clouse E, Yin HH, Costa RM. Endocannabinoid signaling is critical for habit formation. Front Integr Neurosci. 2007;1:6. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.006.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu C, Gupta J, Chen JF, Yin HH. Genetic deletion of A2A adenosine receptors in the striatum selectively impairs habit formation. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15100–15103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Research Council (US) Committee on Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research . Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.