Abstract

Background

There is a growing interest in studying the influence of child-care center policies on the health of preschool-aged children.

Objective

To develop a reliable and valid instrument to quantitatively evaluate the quality of written nutrition and physical activity policies at child-care centers.

Design

Reliability and validation study. A 65-item measure was created to evaluate five areas of child-care center policies: nutrition education, nutrition standards for foods and beverages, promoting healthy eating in the child-care setting, physical activity, and communication and evaluation. The total scale and each subscale were scored on comprehensiveness and strength.

Setting

Analyses were conducted on 94 independent policies from Connecticut child-care centers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program.

Statistical analyses performed

Intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to measure inter-rater reliability, and Cronbach’s α was used to estimate internal consistency. To test construct validity, t tests were used to assess differences in scores between Head Start and non–Head Start centers and between National Association for the Education of Young Children–accredited and nonaccredited centers.

Results

Inter-rater reliability was high for total comprehensiveness and strength scores (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.98 and 0.94, respectively) and subscale scores (intraclass correlation coefficient=0.84 to 0.99). Subscales were adequately internally reliable (Cronbach’s α=.53 to .83). Comprehensiveness and strength scores were higher for Head Start centers than non–Head Start centers across most domains and higher for National Association for the Education of Young Children–accredited centers than nonaccredited centers across some but not all domains, providing evidence of construct validity.

Conclusions

This instrument provides a standardized method to analyze and compare the comprehensiveness and strength of written nutrition and physical activity policies in child-care centers.

At least one in every five children ages 2 to 5 years is overweight or obese (1), and other diet- and activity-related risk factors, such as atherosclerosis and high blood pressure, are evident even in childhood (2). In addition, nationally representative data reveal that preschool-aged children are consuming too many solid fats and added sugars and are not meeting MyPyramid recommendations for whole grains, whole fruits (3), or vegetables (4). Among children ages 2 to 5 years, >40% of fruit is consumed in the form of juice (4), and on a typical day, 70% consume sugar-sweetened beverages (5). Evidence that dietary (6) and physical activity behaviors (7) are established early in life and may persist with time, highlights the importance of early exposure to healthy foods and physical activity for all children.

In the United States, almost 60% of children ages 3 to 6 years are enrolled in child-care centers (8), making centers an important setting for obesity and chronic disease prevention. It is recommended that full-day child-care programs provide one-half to two thirds of children’s daily nutrition needs (9,10), and studies suggest that the center a child attends may be the strongest predictor of physical activity level (11-13). Yet, outside of regulations for Head Start programs and centers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), there are no federal regulations for nutrition or physical activity for children ages 3 to 5 years in child-care facilities (14). Instead, each state is responsible for licensing and regulation of child-care programs, and a recent analysis found that nutrition, physical activity, and media use regulations were weak and varied widely within and among states (15). No state required child-care centers to meet nutrient-based standards, and only two states instructed compliance with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) (15). A review by Benjamin and colleagues found that although 80% of states required water to be freely available in child-care centers and 63% of states prohibited forcing children to eat, only seven states put any restrictions on serving sugar-sweetened beverages and only three states required a specific amount of time spent in physical activity in child-care centers (16).

CACFP and Head Start regulations, which only apply to participating programs, are similarly lacking in specific nutrition standards. CACFP, which provides federal reimbursements to eligible child-care centers and other programs for meals and snacks, requires only that meals and snacks include a minimum number of servings from the following food categories: fluid milk; vegetables, fruit or 100% juice; grains or bread; and meat or meat alternates (17). The Head Start program, which provides federal grants to local preschools serving economically disadvantaged children, is governed by a more comprehensive set of regulations addressing wellness, such as those that ensure food is not used as a reward; foods served are high in nutrients and low in fat, sugar, and salt; sufficient time, space, equipment, and adult guidance is provided for active play; and nutrition education is provided to families (10). However, neither federal program requires quantitative nutrient-based limits or compliance with the DGA. Likewise, quantitative limits are absent from standards developed by nongovernmental organizations, such as the National Association for the Education of Young Children, which requires accredited preschools to follow CACFP food guidelines (18). Limited nutrition standards at the state and federal levels may be linked to the poor nutritional quality reported in many studies examining foods consumed by children in child-care centers (19-22).

Several studies have examined the scope and strength of state regulations for nutrition and physical activity in the child-care setting (15,22,23), but little is known about the content of policies written by administrators at individual child-care centers. Although the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act (2004) required school districts participating in federally reimbursed school meal programs to develop local school wellness policies (typically for grades K through 12), the law did not apply to child-care programs (24). Therefore, wellness policies may go unwritten in the child-care setting. Unless policies are written, policy communication, implementation, compliance, and enforcement may be compromised. Written policies can help set clear expectations for child-care providers and can serve as a means through which centers may be held accountable for their practices. Currently, wellness-related policies at specific child-care centers are variable in content and format and are typically dispersed throughout staff and parent handbooks. Policies in these handbooks may comprise only a subset of all policies at a center because some regulations are less relevant to these audiences, such as those pertaining to outdoor equipment or building upkeep. There is also wide variation in the length and detail of staff and parent handbooks.

To the extent that they are followed and enforced, written policies have great potential for preventing chronic diseases later in life by ensuring that children learn and practice good nutrition and physical activity habits (25). The purpose of this study was to describe the development and psychometric properties of an instrument—the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool—to quantitatively evaluate the comprehensiveness (breadth of areas covered) and strength (degree to which policies include specific and directive language) of written nutrition and physical activity policies at preschools and child-care centers for comparative analyses. This study builds upon a similar instrument developed by Schwartz and colleagues for assessing the strength and comprehensives of school wellness policies for grades K (kindergarten) through 12 (26).

METHODS

Overview

This study was designed to test psychometric properties (range, internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and construct validity) of an instrument to abstract child-care center wellness policies. All Connecticut child-care centers participating in CACFP as of January 2008 (n=221) were sent a letter requesting all documents containing health-related policies. Policy documents were returned for 210 child-care centers, resulting in a response rate of 95.0%.

In this sample, many child-care centers were licensed to be satellite sites of larger entities (sponsors), and other centers operated independently (the sponsor and the center are the same entity). Because sponsors often dictate uniform policies for the sites within their domain, 140 of 210 centers had policies identical to those of at least one other center, while 70 centers had distinct policies. After excluding duplicates, the 140 policies identical to at least one other policy reduced to 24 distinct policies, resulting in an analytic sample of 94 distinct policies. Because child-care centers are not mandated to have specific wellness policies, child-care policies related to wellness are woven into multiple documents, such as parent and staff orientation handbooks. An average of two documents per center were collected, including 199 parent or general handbooks, 132 staff handbooks, 7 parent notifications, and 89 documents that did not fall into these categories. For each center, the set of all documents sent were rated as a single policy for that center. The Yale Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

Instrument Development

A review of relevant federal health standards was conducted in 2008, which included Head Start Performance Standards (10) and CACFP meal pattern requirements (27), as well as voluntary standards, including Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards (28), National Association for the Education of Young Children Early Childhood Program Standards and Accreditation Criteria (18), National Association for Sport and Physical Education Physical Activity Guidelines for Children Birth to Five Years (29), 2005 DGA (30), Position of the American Dietetic Association (ADA): Benchmarks for Nutrition Programs in Child Care Settings (9), and American Heart Association recommendations on dietary sugars (31). In addition, content of the school wellness coding system developed by Schwartz and colleagues (26), the Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care instruments (32), and a sample of Connecticut child-care policies were reviewed. In 2011, the 2010 DGA were also reviewed to ensure consistency of the instrument with the most current dietary guidelines (33). All relevant standards and items (eg, provision of whole grains, frequency of outdoor time) were extracted and grouped into major categories (eg, nutrition education and physical activity) based on content similarities, resulting in an initial pool of 95 standards that served as the basis for potential items to be included in the instrument.

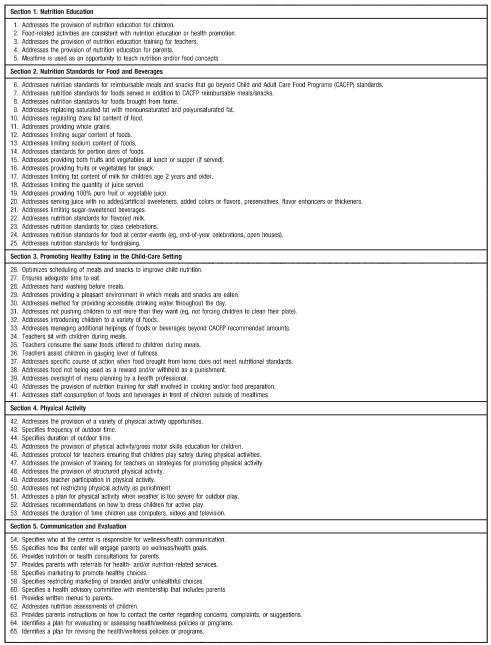

To balance comprehensiveness with parsimony, the number of items was reduced by eliminating overlapping standards and standards only marginally related to healthy eating, physical activity, or policy communication and evaluation. Once drafted, instrument items were piloted and refined through an iterative process of rating policies, reviewing score discrepancies, and revising decision rules. Instrument drafts were reviewed by child-care center directors and the Nutrition Education Coordinator at the Connecticut State Department of Education, who is a registered dietitian responsible for coordinating state-wide training, technical assistance, and resource development on healthy eating and physical activity for child-care centers. Instrument development was also informed by child-care center site visits and interviews with child-care center directors (34). Based on the content grouping of items as well as reviews of expert opinion, documents, and standards, five policy domains emerged: Nutrition Education; Nutrition Standards for Foods and Beverages; Promoting Healthy Eating in the Child Care Setting; Physical Activity; and Communication and Evaluation. Although development of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool was informed in part by the K through 12 wellness policy coding system (26), differences in specific items and domains relevant to early childhood development make the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool distinct. For instance, this instrument does not include a separate physical education section because formal physical education is not a separate aspect of child-care curricula at this time. Instead, the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool contains a physical activity subscale encompassing policies appropriate for child care, such as ensuring the provision of structured physical activity, ensuring a minimum duration and frequency of outdoor time, and limiting daily screen time. The Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool also includes a section entitled “Promoting Healthy Eating in the Child Care Setting” that encompasses timing, procedures, and staff behaviors for mealtimes and other aspects of the child-care environment related to healthy eating, such as availability of drinking water. Figure 1 displays the 65 content items contained in five subscales of the instrument.

Figure 1.

Titles of subscales and content items of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool.

Rater Training

Both raters (authors J.F. and E.K.) had previous experience rating K through 12 wellness policies and had received training on the use of a similarly structured school wellness coding system (26); training of new raters for this previous coding system involved having them rate several policies and discuss score discrepancies with an experienced rater until such discrepancies were minimized. Therefore, minimal training was required for the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool and was limited to a close read of the codebook and discussions between the raters on policy statements that were deemed ambiguous.

Rating Scheme

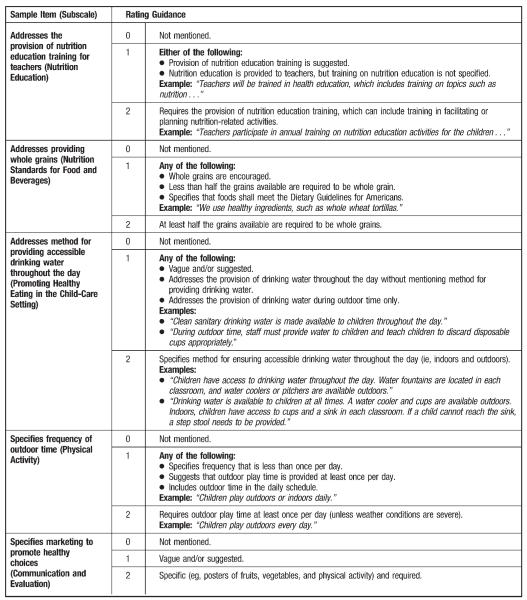

A child-care center policy document is assigned a rating of 0, 1, or 2 for each of 65 items contained in the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool. Ratings are assigned based on the following general criteria: If a center policy does not mention an item, the policy would receive a 0 for that item; if the item is mentioned as a recommendation or with vague language, the policy would receive a 1 for that item; and if the item is addressed with specific and directive language, the policy would receive a 2 for that item. The degree of specificity required for a rating of a 2 sometimes varied based on the context of a particular item. To distinguish between a rating of 1 and 2, policy raters used the scenario of a parent approaching a child-care center administrator with a wellness-related concern. If the policy language did not clarify the center’s action or position on that issue, it was rated as a one; if the parent and administrators could easily determine from the policy language whether or not the center is compliant, the item was rated as a 2. To further assist in assigning ratings, the assessment tool contains guidance on commonly encountered policy language and examples of policy statements that should receive ratings of 1 or 2. Figure 2 illustrates examples of rating guidance provided in the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool. For each subscale, comprehensiveness and strength scores are calculated based on the rating of individual items within the subscale. The comprehensiveness score is calculated by multiplying 100 by the proportion of subscale items with a rating of 1 or 2, indicating that the item was mentioned within a policy. The strength score is calculated by multiplying 100 by the proportion of subscale items with a rating of a 2, indicating that the policy item is mentioned with specific and directive language. Total comprehensiveness and total strength scores for a policy are calculated by taking the average of the five subscale scores so that each subscale receives equal weight. Five items may receive a rating of “NA” if the item does not apply to the particular policy. Items rated as NA should not be included in the total number of items used for scoring a particular section.

Figure 2.

Sample of policy items and rating guidance from each subscale of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool.

Because state policies and regulations for child-care centers supersede the authority of local child-care policies, some items may receive state-level default ratings. For example, the Connecticut statutes and regulations state: “Children and staff shall wash their hands with soap and water before eating or handling food” (35). Therefore, all policies from Connecticut child-care centers and preschools received a default rating of 2 for the item addressing hand washing. In addition, centers designated as Head Start centers or those with accreditation from the National Association for the Education of Young Children received some default ratings on items relevant to the regulations (for Head Start) and guidelines (for National Association for the Education of Young Children) that these child-care centers must follow.

Statistical Analysis

The instrument’s psychometric properties were evaluated by testing inter-rater reliability, internal consistency, and construct validity.

Inter-Rater Reliability

A random subsample of 18 documents was coded by both raters. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to examine inter-rater reliability for the comprehensiveness and strength scores for each subscale as well as the total comprehensiveness and strength scores.

Internal Consistency

Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated for each subscale representing a domain of policy quality, using the total sample of distinct policies (n=94).

Construct Validity

Construct validity was assessed by comparing policy quality scores of Head Start centers to those of non–Head Start centers, and centers accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children to nonaccredited centers. It was hypothesized that because Head Start centers are required to follow more comprehensive and stricter regulations than non–Head Start centers, the policy quality scores of these centers would be higher across both comprehensiveness and strength. It was also hypothesized that National Association for the Education of Young Children centers would have higher scores than non–National Association for the Education of Young Children centers, but that the differences would be smaller than those between Head Start and non–Head Start centers as National Association for the Education of Young Children accreditation guidelines are less strict than Head Start regulations. Differences in scores were assessed by simple t tests using the full sample of distinct policy documents (n=94). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (release 17.0.0, 2008, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Across all of the policies, the mean total comprehensiveness score (out of 100) was 47.8 (±13.4; range=19 to 74) and the mean total strength score (out of 100) was 23.9 (±10.2; range=5 to 55). Both scores demonstrated good range and variability (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean±standard deviation and range of Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool scores (n=94 policy documents)

| Mean±SDa | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensiveness scores | ||

| Nutrition Education | 45.5±25.3 | 20-100 |

| Nutrition Standards | 12.3±10.9 | 0-37 |

| Promoting Healthy Eating | 54.8±18.8 | 19-92 |

| Physical Activity | 58.2±12.4 | 17-83 |

| Communication and Evaluation | 70.2±14.6 | 25-83 |

| Total comprehensiveness score | 47.8±13.4 | 19-74 |

| Strength scores | ||

| Nutrition Education | 27.7±19.5 | 0-100 |

| Nutrition Standards | 2.4±4.3 | 0-21 |

| Promoting Healthy Eating | 37.1 ±15.7 | 13-81 |

| Physical Activity | 29.0±9.4 | 8-50 |

| Communication and Evaluation | 23.1 ±17.7 | 0-67 |

| Total strength score | 23.9±10.2 | 5-55 |

SD=standard deviation.

Several individual items within the instrument showed limited range and variability in this sample. Any item with zero variance was excluded from psychometric analyses, as the calculation of ICC coefficients and Cronbach’s α require item variance. However, items with limited variability were not deleted from the final instrument because of theoretical importance (eg, items addressing saturated fat, sodium, and sugar content of foods). Interrater reliability (ICC) for the total comprehensiveness score was 0.98 and for the subscale scores ranged from 0.84 to 0.97 (Table 2). Values were similarly high for the strength scores, with an ICC of 0.94 for the total strength score and a range of 0.89 to 0.99 for the subscales.

Table 2.

Intraclass correlation coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for inter-rater reliability of strength and comprehensiveness scores on the five subscales and total scale of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool (subsample: n=18 policy documents)

| Comprehensiveness | Strength | |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrition | ||

| Education | 0.95 (0.87-0.98) | 0.95 (0.87-0.98) |

| Nutrition | ||

| Standards | 0.96 (0.90-0.99) | 0.94 (0.84-0.98) |

| Promoting Healthy | ||

| Eating | 0.97 (0.92-0.99) | 0.99 (0.96-1.00) |

| Physical Activity | 0.93 (0.83-0.97) | 0.89 (0.73-0.96) |

| Communication | ||

| and Evaluation | 0.84 (0.62-0.94) | 0.91 (0.77-0.95) |

| Total | 0.98 (0.94-0.99) | 0.94 (0.85-0.98) |

The five subscales were found to have varying internal consistency. Cronbach’s coefficient α values were as follow: 0.66 for Nutrition Education, 0.64 for Nutrition Standards for Foods and Beverages, 0.83 for Promoting Healthy Eating in the Child Care Setting, 0.53 for Physical Activity, and 0.82 for Communication and Evaluation.

Head Start status was significantly associated with higher comprehensiveness and strength scores across almost every domain, while National Association for the Education of Young Children status was significantly associated with higher scores in a few domains (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean±standard deviation of Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool scores, by Head Start status and National Association for the Education of Young Children accreditation status (n=94 policy documents)a

| Head Start (n=24) |

Non-Head Start (n=70) |

National Association for the Education of Young Children (n=69) |

Non–National Association for the Education of Young Children (n=25) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensiveness scores | ||||

| Nutrition Education | 78.3±15.5 | 34.3±16.7*** | 42.9±22.8 | 52.8±30.5 |

| Nutrition Standards | 25.6±6.0 | 7.8 ±8.1*** | 11.7±10.3 | 14.2±12.4 |

| Promoting Healthy Eating | 75.2 ±7.8 | 47.7±16.1*** | 57.1 ±16.6 | 48.5±22.9 |

| Physical Activity | 64.3±9.2 | 56.3±12.7** | 62.4±7.8 | 47.0±15.2*** |

| Communication and Evaluation | 83.3 ±0.0 | 65.7±14.4*** | 74.2±6.4 | 59.3±23.2** |

| Total score | 65.7±5.0 | 42.2±9.8*** | 49.1 ±10.5 | 44.4±18.9 |

| Strength scores | ||||

| Nutrition Education | 50.0±17.7 | 20.0 ±13.2*** | 29.0±15.5 | 24.0±27.7 |

| Nutrition Standards | 4.4±5.5 | 1.7±3.6* | 2.3 ±4.1 | 2.6±4.9 |

| Promoting Healthy Eating | 57.9±9.8 | 29.9±9.7*** | 38.8±14.6 | 32.6±17.7 |

| Physical Activity | 25.4±11.4 | 30.2±8.4 | 32.3±6.4 | 20.0±10.8*** |

| Communication and Evaluation | 46.5±13.2 | 15.1 ±10.5*** | 24.4±17.7 | 19.7±17.7 |

| Total score | 36.8±7.3 | 19.3 ±6.4*** | 25.4±9.1 | 19.8 ±11.8* |

P values are for t tests comparing mean scores of Head Start to non–Head Start centers and National Association for the Education of Young Children to non–National Association for the Education of Young Children centers.

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

DISCUSSION

The Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool was designed to rate the strength and comprehensiveness of written nutrition and physical activity policies in child-care centers. Psychometric analyses demonstrate good range in subscale scores, suggesting that the tool overall is not vulnerable to floor or ceiling effects and can distinguish between low- and high-quality policies. As expected, several individual items were found rarely or never in the sample of policy documents reviewed. Nonetheless, these items remain in the tool because they represent important aspects of nutritional quality and are expected to show greater variability as child-care centers develop formal wellness policies in the future. Excellent inter-rater reliability was achieved for all subscales, suggesting that the tool produces replicable results. Internal consistency values were moderate overall. This may be because the data were drawn from multiple documents from each site, introducing substantial heterogeneity. Internal consistency is expected to improve when the tool is used to rate more structured, cohesive wellness policies. The observed differences between Head Start and non–Head Start centers provide strong evidence of construct validity, since it was predicted that Head Start preschools would have policies with stronger language and more breadth because of their regulatory status and institutional culture. It was also predicted that policies from National Association for the Education of Young Children-accredited programs would be stronger and more comprehensive than those from non–National Association for the Education of Young Children programs, and this was the case for some subscales. However, these differences were expected to be smaller than those observed for Head Start status, because National Association for the Education of Young Children guidelines are less comprehensive and not associated with as strong sanctions for noncompliance as are Head Start regulations (although accreditation is an important motivator).

There is growing interest in studying nutrition and physical activity policies in the child-care setting. Previous work has focused mostly on state regulations, and few studies have measured policies at the child-care center level. Dowda and colleagues used a structured interview with preschool administrators to assess the presence of physical activity policies and practices but did not review written policies (36). Ward and colleagues developed the environment and policy assessment and observation instrument, which included a document review evaluating a mix of written policy and documentation of practices (eg, safety checks) pertaining to nutrition and physical activity (32). The Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool provides a unique tool to researchers, because it is specific to written policies, evaluates both the scope and strength of policy language, and encompasses a wide range of content areas.

Written policies have the potential to improve child health, yet only one study has evaluated the relationship between written policies and outcomes in the child-care setting. A weak association was observed between presence of written physical activity policies and physical activity levels, but the scope of policies assessed was limited (37). In the same study, the subscale most strongly associated with physical activity levels included observed provision of structured physical activity, outdoor play, and total minutes of active opportunity—most of which are addressed as policy items in the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool. Another study evaluating how observed practices predict physical activity found that lower electronic media use, portable equipment on the playground, and larger playgrounds predicted higher physical activity levels and less sedentary time (38). Because these are also practices that overlap with content areas of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool, it is possible that the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool scores could predict physical activity and other outcomes to the extent that policies are followed.

Written program-level wellness policies are important not only because of the potential to affect practices, but also because written policies offer a way through which administrators and families can evaluate program performance. Recently, the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity issued recommendations that states should be encouraged to strengthen licensing standards regarding nutrition, physical activity, and screen time and that the federal government should look for opportunities in programs such as CACFP and Head Start to base policies and practices on current scientific evidence (39). In addition, the American Dietetic Association developed new benchmarks for nutrition in child care and suggested that these benchmarks be achieved through policy and regulation (40). As state-licensing and federal program standards are strengthened, such standards are likely to be integrated into center-level policies. However, without a legal requirement for written wellness policies in the child-care setting, written policies may remain widely variable in detail and scope. Given that Head Start programs scored higher than non–Head Start programs on both comprehensiveness and strength, child-care administrators who would like to write wellness policies may consider using Head Start Program Performance Standards (10), the current Dietary Guideline for Americans (33), Position of the ADA: Benchmarks for Nutrition in Child Care (40), and examples in the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool as model policies.

The Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool may provide an important starting point for studying predictors of center policy quality and how such policies may relate to center practices and child health. There is preliminary evidence of adequate to excellent psychometric properties, and there is considerable overlap between content of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool and the new independently developed ADA benchmarks for nutrition in child care (40). However, because the study of child-care nutrition and physical activity policy is in its infancy, items on the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool should be interpreted as promising policy strategies. Future studies should seek to provide evidence of the relative importance of each policy item, and as empirical evidence accumulates, the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool may benefit from further refinement.

The following limitations should be considered for future uses of the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool. Policies rated were from child-care centers participating in CACFP from one state, and thus the results may have limited generalizability. In addition, policy documents collected from preschools and child-care centers varied greatly in the amount of information they contained, as they were not strictly wellness policies. Because the lack of a written policy may not necessarily indicate lack of a practice, the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool should be used only to assess written policies and is not appropriate for the evaluation of overall program quality or practices. Also, this study was not able to assess predictive validity. Future research should test whether Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool scores predict the quality of the child-care wellness environment, nutrition and physical activity practices, and child nutrition and activity levels. Finally, policy raters for this study had previous policy rating experience, so the precise degree of training required to achieve high inter-rater reliability should be determined in future studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool is, to our knowledge, the first instrument developed to quantitatively assess both the strength and comprehensiveness of written policies on nutrition and physical activity at child-care centers. This instrument provides a means through which written policies can be compared across programs and will be useful for studying predictors or consequences of child-care wellness policies.

Interest in the potential effects of the child-care environment on young children’s nutrition and physical activity is growing, and this instrument can help to fill the gap in knowledge about the characteristics of policies at the child-care center level. Future studies should assess its predictive validity and performance using a nationally representative sample of child-care policies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Susan Fiore, MS, RD; Gabrielle Grode, MPH; Meghan O’Connell, MPH; Cynthia Olson, MEd; and Patricia Strout for valuable feedback on the Wellness Child Care Assessment Tool.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This article was supported by grant no. 63150 from Healthy Eating Research and grant no. 64093 from Active Living Research, both national programs of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Further financial support was provided by the Rudd Foundation. J. Falbe’s work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Training Grant in Academic Nutrition no. T32 DK007703-16.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

JENNIFER FALBE, Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

ERICA L. KENNEY, Department of Society, Human Development, and Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

KATHRYN E. HENDERSON, Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

MARLENE B. SCHWARTZ, Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenson GS, Srnivasan SR. Cardiovascular risk factors in youth with implications for aging: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. J Nutr. 2010;140:1832–1838. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorson BA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Taylor CA. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intakes in US children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1604–1614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pate RR, Baranowski T, Dowda M, Trost SG. Tracking of physical activity in young children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:92–96. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199601000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics . America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2009. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Position of the American Dietetic Association: Benchmarks for Nutrition Programs in Child Care Settings. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:979–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Head Start Bureau [Accessed February 8, 2009];Head Start Program Performance Standards and other regulations. http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/Program%20Design%20and%20Management/Head%20Start%20Requirements/Head%20Start%20Requirements.

- 11.Finn K, Johannsen N, Specker B. Factors associated with physical activity in preschool children. J Pediatr. 2002;140:81–85. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pate RR, Pfeiffer KA, Trost SG, Ziegler P, Dowda M. Physical activity among children attending preschools. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1258–1263. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1088-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pate RR, McIver K, Dowda M, Brown WH, Addy C. Directly observed physical activity levels in preschool children. J Sch Health. 2008;78:438–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Health Eating Research [Accessed August 8, 2010];Promoting Good Nutrition and Physical Activity in Child-Care Settings (Research Brief) 2007 May; http://www.healthyeatingresearch.org/images/stories/her_research_briefs/her%20child%20care%20setting%20research%20 brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaphingst KM, Story M. Child care as an untapped setting for obesity prevention: State child care licensing regulations related to nutrition, physical activity, and media use for preschool-aged children in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamin SE, Cradock A, Walker EM, Slining M, Gillman MW. Obesity prevention in child care: A review of US state regulations. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service [Accessed October 8, 2008];Child & Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns. 2008 http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/programbasics/meals/meal_patterns.htm.

- 18.National Association for the Education of Young Children . NAEYC Early Childhood Program Standards and Accreditation Criteria: The Mark of Quality in Early Childhood Education. National Association for the Education of Young Children; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Dietary intakes in North Carolina child-care centers: Are children meeting current recommendations? J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:718–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mier N, Piziak V, Kjar D, et al. Nutrition provided to Mexican-American preschool children on the Texas-Mexico border. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padget A, Briley ME. Dietary intakes at child-care centers in central Texas fail to meet Food Guide Pyramid recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamin SE, Copeland KA, Cradock A, et al. Menus in child care: A comparison of state regulations with national standards. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cradock AL, O’Donnell EM, Benjamin SE, Walker E, Slining M. A review of state regulations to promote physical activity and safety on playgrounds in child care centers and family child care homes. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(suppl 1):S108–S119. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s1.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Child Nutrition and Women, Infants, and Children Reauthorization Act of 2004. Public L No. 108-265, Stat 2507, §204. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz MB, Lund AE, Grow HM, et al. A comprehensive coding system to measure the quality of school wellness policies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service [Accessed October 8, 2008];Child & Adult Care Food Program Meal Patterns. 2008 http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/programbasics/meals/meal_patterns.htm.

- 28.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education . Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Out-of-Home Child Care Programs. 2nd ed American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove Village, IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) Active Start: A Statement of Physical Activity Guidelines for Children Birth to Five Years. NASPE; Reston, VA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, Sacks F, Steffen LM, Wylie-Rosett J, American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism and the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1011–1020. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward D, Hales D, Haverly K, Marks J, Benjamin S, Ball S, Trost S. An instrument to assess the obesogenic environment of child care centers. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:380–386. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services . Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henderson KE, Grode GM, Middleton AE, Kenney EL, Falbe J, Schwartz MB. Validity of a measure to assess the child care nutrition and physical activity environment. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1306–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.State of Connecticut Department of Public Health, Community Based Regulation Section . Statutes and Regulations for Licensing Child Day Care Centers and Group Day Care Homes. State of Connecticut Department of Public Health; Hartford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowda M, Pate RR, Trost SG, Almeida MJ, Sirard JR. Influences of preschool policies and practices on children’s physical activity. J Commun Health. 2004;29:183–196. doi: 10.1023/b:johe.0000022025.77294.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bower JK, Hales DP, Tate DF, Rubin DA, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. The childcare environment and children’s physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowda M, Brown WH, McIver KL, Pfeiffer KA, O’Neill JR, Addy CL, Pate RR. Policies and characteristics of the preschool environment and physical activity of young children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e261–266. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity [Accessed November 1, 2010];Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity within a Generation. 2010 http://www.letsmove.gov/pdf/TaskForce_on_Childhood_Obesity_May2010_FullReport.pdf. Published May 2010.

- 40.Benjamin Neelon SE, Briley ME. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Benchmarks for nutrition in child care. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]