Abstract

Social cognitive impairments and negative symptoms are core features of schizophrenia closely associated with impaired community functioning. However, little is known about whether these are independent dimensions of illness and if so, whether individuals with schizophrenia can be meaningfully classified based on these dimensions (SANS) and potentially differentially treated. Five social cognitive measures plus Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores in a sample of 77 outpatients produced 2 distinct factors—a social cognitive factor and a negative symptom factor. Factor scores were used in a cluster analysis, which yielded 3 well-defined groupings—a high negative symptom group (HN) and 2 low negative symptom groups, 1 with higher social cognition (HSC) and 1 with low social cognition (LSC). To make these findings more practicable for research and clinical settings, a rule of thumb for categorizing using only the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test and PANSS negative component was created and produced 84.4% agreement with the original cluster groups. An additional 63 subjects were added to cross validate the rule of thumb. When samples were combined (N = 140), the HSC group had significantly better quality of life and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores, higher rates of marriage and more hospitalizations. The LSC group had worse criminal and substance abuse histories. With 2 common assessment instruments, people with schizophrenia can be classified into 3 subgroups that have different barriers to community integration and could potentially benefit from different treatments.

Keywords: social cognition, negative syndrome, community functioning, SANS, PANSS, MSCEIT

Introduction

Social cognition is a topic that has gained much interest for its potential to explain the social dysfunction and disability associated with schizophrenia and related disorders. Social cognition is a broad construct, and scientific efforts are underway to capture its relevant features by developing and exploring measures of affect recognition, Theory of Mind (ToM), social attribution, empathy, and social problem solving. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) included one such measure, the managing emotions subtest of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT)1 , 2 as a single representative of this broad domain, but a recent study by Mancuso et al3 found support for 3 dimensions of social cognition based on a factor analysis of 4 measures with 8 variables. They named these factors hostile attributional style, lower level social cue detection, and higher level inferential and regulatory processes. They further determined that the latter 2 were related to proxy measures of social function (UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment4 and The Maryland Assessment of Social Competence [MASC]5) and weakly related to a social functioning subscale of the Community Adjustment Form.6 None of the factors were significantly correlated with negative symptoms as measured by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS7). This was an important finding because negative symptoms may also have a direct impact on social functioning and this result suggested that social cognition and negative symptoms may be 2 relatively independent causes of dysfunction and disability.

In a study of social cognition and deficit evaluations, Brunet-Gouet and colleagues8 report modest correlations (r = .20–.34, n = 217, P < .05) between a video-based intention attribution task and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) symptoms of affective blunting, social withdrawal, difficulty of abstraction, conceptual disorganization, and attention deficits. They note that no positive symptom was significantly correlated. Finally, Couture and colleagues9 employed path analysis to determine the relationships between negative symptoms, ToM as measured by the Hinting Task,10 social competence as measured by the MASC11, and self-reported functioning. ToM and negative symptoms were correlated −.25 (P < .01), and the final model showed ToM being significantly related to social competence independent of negative symptoms. Also, ToM partially mediated the relationship between neurocognition and social competence. Importantly, negative symptoms and social competence were the only variables in the model that demonstrated a significant direct path to self-reported functioning.

The purpose of the current study was to determine whether measures of negative symptoms and social cognition represent 2 distinct dimensions of impairment in schizophrenia and to what extent these may explain concurrent community functioning and functional histories (ie, criminal, marital, substance abuse, vocational). We chose to begin our exploration by entering negative symptom measures and social cognitive measures into a principal component analysis to determine whether: (1) orthogonal dimensions would clearly place negative symptoms and social cognition into 2 separate factors, as would be suggested from the results of Mancuso and colleagues or (2) that negative symptoms share common variance with certain social cognitive measures on a single dimension, as might be suggested from the correlations found by Brunet-Gouet et al8 and Couture et al9 The second step in this exploration was to use these dimensions in a cluster analysis to create meaningful groupings and then to compare those groupings on their current community functioning and functional history.

Results of the first 2 steps allowed us to add a second phase to the study. In this second phase, we sought to make the clusters practicable for other researchers by creating a “rule of thumb” for characterizing participants into these groupings by selecting 2 common assessment measures (PANSS negative component and MSCEIT from the MCCB) and identifying classification cut-points in these data to represent the original cluster centers. To cross validate the rule of thumb, a holdout sample of 63 subjects was classified into subgroups by these cut-points and compared on the same community function measures as the original cluster-derived subgroups. We hypothesized that these groupings would yield results similar to those from the comparison of cluster groupings, thereby lending support for the value of this method of classification. Other researchers who might not use exactly the same measures as those in the cluster analysis, but who have PANSS and MCCB data, would then be able to take advantage of the rule of thumb to create groupings similar to those used in the current study. Moreover, identifying these subgroups of patients with different barriers to community integration could be valuable for development and provision of treatments more specific to individual pathology.

Methods

Participants

For the first phase, participants were 77 adult outpatients (table 1) meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth revision, (DSM-IV12) criteria for a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID13). Participants were recruited from an urban community mental health center (CMHC) for an ongoing study of cognitive training and supported employment (Clinical Trials.gov #NCT00339170) and were referred by their clinicians because they expressed a desire for returning to work. Participants were clinically stable (no hospitalizations, emergency room visits, homelessness, or substance abuse in the past 30 days), without evidence of current neurological disease, brain injury, or developmental disability and proficient in English. For the second phase of the study, 63 participants from other psychiatric rehabilitation studies with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria performed by the authors at CMHC, and the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System were used as a holdout sample to cross validate the subgroup classifications established in the first sample.

Table 1.

First Phase Participant Characteristics for Demographic, Clinical, and Social Cognitive Measures (N = 77)

| All subjects N = 77 | HN (1) n = 24 | HSC (2) n = 27 | LSC (3) n = 26 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 43 (55.8) | 18 (75) | 13 (48.1) | 12 (46.2) |

| Female | 34 (44.1) | 6 (25) | 14 (51.9) | 14 (53.8) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 4 (5.1) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.8) |

| Separated/divorced | 11 (14.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) | 5 (19.2) |

| Single | 61 (79.2) | 23 (95.8) | 18 (66.7) | 20 (76.9) |

| Widowed | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) |

| Schizophrenia diagnosis | ||||

| Disorganized | 1 (1.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Paranoid | 30 (38.9) | 8 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | 12(46.2) |

| Residual | 12 (15.5) | 6 (25.0) | 3 (11.1) | 3 (11.5) |

| Undifferentiated | 8 (10.3) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (3.8) |

| Schizoaffective | 25 (32.4) | 5 (20.8) | 10 (37.0) | 10 (38.5) |

| Psychosis disorder NOS | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) |

| Medications | ||||

| Atypical | 50 (64.9) | 15 (62.5) | 20 (74.1) | 15 (57.7) |

| Conventional | 13 (16.8) | 3 (12.5) | 5 (18.5) | 5 (19.2) |

| Both | 4 (5.1) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) |

| None | 10 (12.9) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (7.4) | 5 (19.2) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 43.4 (10.4) | 37.1 (10.8) | 44.5 (8.8) | 48.1 (8.8) |

| Estimated IQa | 91.3 (15.2) | 94.1 (17.3) | 97.7 (14.8) | 82.2 (8.1) |

| Education | 12.7 (2.4) | 13.1 (3.2) | 13.0 (2.0) | 12.1 (1.8) |

| Age of onset | 22.7 (9.9) | 23.2 (7.7) | 22.0 (11.8) | 23.0 (9.9) |

| Lifetime # of hospitalizations | 7.8 (9.07) | 6.9 (10.4) | 8.6 (9.7) | 7.7 (7.0) |

| GAF | 42.3 (7.9) | 41.1 (6.5) | 44.4 (9.4) | 41.1 (7.1) |

| PANSS | ||||

| Positive | 15.1 (5.4) | 15.2 (5.3) | 15.9 (5.8) | 14.3 (5.3) |

| Negative | 15.9 (6.6) | 23.7 (3.9) | 12.4 (4.0) | 12.4 (4.3) |

| Cognitive | 15.5 (4.3) | 16.7 (4.9) | 14.5 (4.1) | 15.5 (3.8) |

| Hostility | 6.4 (3.0) | 6.5 (2.7) | 6.5 (3.5) | 6.2 (2.) |

| Emotional discomfort | 8.8 (3.7) | 9.5 (3.3) | 8.7 (4.3) | 8.3 (3.4) |

| SANS | ||||

| Flattening/blunting | 7.8 (.89) | 15.4 (6.9) | 2.9 (3.7) | 5.2 (6.2) |

| Alogia | 3.4 (3.5) | 7.2 (2.4) | 1.3 (1.9) | 2.1 (2.8) |

| Avolition/apathy | 6.4 (4.9) | 9.9 (4.8) | 4.7 (4.2) | 4.8 (4.1) |

| Anhedonia/asociality | 11.5 (6.4) | 15.7 (5.3) | 9.2 (6.6) | 10.1 (5.5) |

| Social cognition measures | ||||

| SAT-MC–score correct | 10.8 (4.5) | 11.4 (3.5) | 13.4 (4.3) | 7.7 (3.6) |

| BLERT-score correct | 12.8 (3.3) | 13.6 (2.5) | 14.8 (2.6) | 9.8 (2.6) |

| Hinting score | 16.7 (2.2) | 15.7 (2.4) | 17.3 (2.0) | 16.9 (2.0) |

| BORRTI egocentricity | 61.4 (12.2) | 59.1 (11.8) | 57.4 (12.8) | 67.6 (9.69) |

| MSCEIT-MC T-score | 37.6 (13.2) | 39.2 (12.6) | 46.7 (8.8) | 26.5 (9.1) |

Note: HN (1) = High Negative; HSC (2) = Higher Social Cognition; LSC (3) = Low Social Cognition; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAT-MC, Social Attribution Task—Multiple Choice; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test; BORRTI, Bell Object Relations Reality Testing Inventory; MSCEIT, Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test.

Estimated IQ Wechsler Adult Scale of Intelligence III (WAIS-III) full scale deviation quotient for sum of scaled scores for vocabulary and block design dyad. ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons: F(2,74) = 8.92; P < .01 = 1 > 3, 2 > 3.

Measures

Diagnosis and Symptom Assessment.

Diagnosis was made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID12), Symptoms were assessed with the PANSS14 (total score ICC for raters = .88–.98) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS15) (total score ICC for raters = .83–.95). PANSS scores were calculated using 5 component scores: Positive, Negative, Cognitive, Hostility, and Emotional Discomfort.16 The negative component includes passive withdrawal, emotional withdrawal, blunted affect, lack of spontaneity, poor rapport, disturbance of volition, preoccupation, and motor retardation.

Social Cognitive Assessment.

The Social Attribution Task—Multiple Choice Version

Originally developed by Klin17 , 18 and used by Bell and colleagues19 for schizophrenia research, this task is composed of a 64-second animation created by Heider and Simmel20 in which geometric shapes enact a social drama. The animation is shown twice and then short segments are presented followed by multiple-choice questions about the actions depicted. In all, 19 questions are asked with 4 possible responses to each. For example, after being shown a short segment, the respondent is asked, “What is the little triangle trying to do?” and given these choices: “(1) It wants to help the little circle. (2) It wants to help the big triangle. (3) It wants to play with the little circle and with the big triangle. (4) It wants to lock the door.” It is scored for total number correct.

The Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task

This affect recognition task consists of 21 short video clips in which an actor performs 1 of 3 dialogues while portraying 7 different emotions that color the monologues21. The examinee chooses from a list the option that best reflects the affective quality portrayed. Total correct score was used in this study.

The Hinting Task (American Version)

This is a ToM measure consisting of 10 brief scenarios of an interaction between 2 people10,22. One of the characters drops an obvious hint (eg, “Jane, I’d love to wear that blue shirt, but it’s very wrinkled”), and the examinee is asked what was meant. It is scored for total number correct.

Bell Object Relations Reality Testing Inventory

This is a self-report measure with 90 true/false items assessing 4 dimensions of object relations and 3 dimensions of reality testing23. It was developed initially for schizophrenia research and has been found to have strong psychometric properties in a wide variety of applications and to have cross-cultural validity.24 The Egocentricity scale, in particular, has been linked with measures of social functioning.25 Examples of items include: I believe a good mother should always please her children (true); people are never honest with each other (true); and others frequently try to humiliate me (true). T-scores were used in this analysis.

MCCB Social Cognition Index

This is composed of scores from the MSCEIT1, Emotion Management Task (Section D), and Social Management Task (Section H). Respondents evaluate how effective different actions would be in achieving an outcome involving other people (eg, how effective would calling friends or eating healthy be in making someone feel better). T-scores were produced from the scoring software.

Social Functioning Measures

Educational, vocational, marital, substance abuse, and criminal histories were gathered by means of a psychosocial interview performed at intake.

Quality of Life Scale

The Quality of Life Scale (QLS26) is a semi-structured interview assessing various components of functioning, with 21 items rated on a 0–6 Likert-type scale and grouped into 4 domains of function: interpersonal relations, intrapsychic foundations, instrumental role function, and common objects and activities. The total score ranges from 0 to 126, with higher scores indicative of better function (total score ICC for raters = .95–.99).

Procedures

After obtaining written informed consent as approved by the institutional review board, psychologists and/or master’s level researchers collected demographic information and administered social cognitive assessments. Symptom assessment and social functioning measures were performed by Ph.D. level psychologists trained to high levels of inter-rater agreement. Testing was typically completed over 2 sessions, with breaks as need to reduce fatigue and maintain alertness.

Analysis

Measures were checked for their distributional properties using the box-plot function of SPSS (17.0). No cases were identified as extreme outliers based on criteria used in SPSS, thus all data were retained. Analyses were then conducted in 2 phases.

First, the bivariate relationships of the 5 social cognitive measures and 5 negative symptom measures were examined using correlation coefficients, followed by principal components extraction and varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization.

Following data reduction by principal component analysis, the sample was categorized according to differences in social cognition and negative symptom components using K-means cluster analysis. The cluster centers and number of clusters were not predetermined with solutions at 2–5 clusters examined. A box-plot of cluster centers was examined to determine their degree of separation. To confirm that the cluster structure was reproducible, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using Ward’s method, and the resulting dendrogram was inspected for solutions of 2–5 clusters. Consequently, the agreement between the K-means method and the Ward’s method was calculated using coefficient kappa. A discriminant function analysis using all the negative symptom and social cognitive variables was performed to test classification agreement with the cluster solution. One-way ANOVAs compared cluster groups on continuous functional measures (years of education, Global Assessment of Functioning [GAF] score, age of onset of the illness, and QLS total score and subscores26) with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons. In addition, as most of the functional measures were not normally distributed, a categorical analysis using K-independent nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis test) was used for group comparisons. The categorical functional measures were marital status (single, married, separated/divorced, and widowed), number of lifetime hospitalizations (less than 6, 6 or more), schizophrenia subtype (disorganized, paranoid, residual, undifferentiated, schizoaffective, and psychotic disorder NOS), medication type (atypical, conventional, both, and none), prior work experience, defined as continuously employed full time in the same job for a year or more (yes, no), presence of work activity 12 months before study intake (yes, no), lifetime criminal arrests (fewer than 3, 3 or more), time spent in jail (none, 1 day at least), lifetime substance abuse (yes, no), abuse/dependence of alcohol alone (yes, no), and abuse/dependence of alcohol plus other substances (yes, no). We did not correct for experiment-wise error as this was an exploratory analysis. Only tests yielding statistically significant group differences are presented in table 4.

Table 4.

Differences in Social Functioning for Cluster Derived Groups and Cross-Validation Sample Using the Rule of Thumb Classification

| First Phase Sample (N = 77) | Cross-Validation Sample (N = 63) | ||||||||||||

| Cluster Analysis Derived Groups | “Rule of Thumb” Derived Groups | ||||||||||||

| HN (1) (n = 24) Mean (SD) | HSC (2) (n = 27) Mean (SD) | LSC (3) (n = 26) Mean (SD) | F/Chi square | P | Bonferroni post hoc comparisona | HN (1) (n = 12) Mean (SD) | HSC (2) (n = 19) Mean (SD) | LSC (3) (n = 32) Mean (SD) | F/Chi square | P | Bonferroni post hoc comparisonsa | ||

| Age of onset | 23.2 (7.7) | 22.0 (11.8) | 23.0 (9.9) | .106 | .900 | ns | 25.2 (9.3) | 18.6 (6.0) | 24.0 (8.8) | 3.31 | .043 | ns | |

| GAF | 41.1 (6.5) | 44.48 (9.4) | 41.1 (7.1) | 1.56 | .216 | ns | 40.0 (7.9) | 44.1 (9.0) | 42.0 (8.6) | .870 | .424 | ns | |

| QLS total | 42.7 (15.8) | 55.0 (17.1) | 50.0 (22.1) | 2.82 | .066 | ns | 51.3 (10.6) | 63.4 (23.2) | 54.8 (20.0) | 1.67 | .196 | ns | |

| QLS interpersonal | 15.2 (9.9) | 21.4 (8.9) | 19.9 (10.2) | 2.71 | .073 | ns | 15.1 (5.3) | 22.4 (10.3) | 20.3 (10.0) | 2.26 | .112 | ns | |

| QLS intrapsychic | 19.6 (6.6) | 26.1 (7.9) | 22.6 (8.9) | 4.22 | .018 | 2>1 | 22.4 (5.6) | 27.8 (8.1) | 24.4 (8.8) | 1.848 | .166 | ns | |

| QLS objects/activities | 6.7 (1.8) | 7.0 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.2) | 2.33 | .104 | ns | 7.9 (2.4) | 8.1 (1.8) | 6.8 (2.1) | 2.68 | .076 | ns | |

| Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | ||||||||

| Marital Status | 6.69 | .035 | 0.644 | .725 | |||||||||

| Single | 23 (95.8) | 18 (66.7) | 20 (79.2) | 1>3>2 | 9 (75.0) | 12 (63.2) | 20 (62.5) | ||||||

| Ever Married | 1 (4.2) | 9 (33.3) | 6 (20.8) | 2>3>1 | 3 (25.0) | 7 (36.8) | 12 (37.5) | ns | |||||

| # Lifetime hospitalizations | 2.59 | .273 | ns | 5.79 | .055 | ||||||||

| less than 6 | 16 (66.7) | 12 (44.4) | 15 (57.7) | n = 62b | 7 (58.3) | 4 (21.1) | 16 (51.6) | ||||||

| 6 or more | 8 (33.3) | 15 (55.6) | 11 (42.3) | 5(41.7) | 15(78.9) | 15(56.5) | ns | ||||||

| # Lifetime criminal arrests (n = 76)b | 6.81 | .033 | 7.88 | .019 | |||||||||

| 2 or less | 17(70.8) | 22(81.5) | 12(48.0) | 2>1>3 | n = 21b | 4 (80.0) | 7 (77.8) | 1 (14.3) | 2>1>3 | ||||

| More than 2 | 7 (29.2) | 5 (18.5) | 13 (52.0) | 3>1>2 | 1 (20.0) | 2 (22.2) | 6 (85.7) | 3>2>1 | |||||

| Lifetime substance abuse | 0.384 | .825 | 6.29 | .043 | |||||||||

| Yes | 17 (70.8) | 21 (77.8) | 20 (76.9) | n = 34b | 5 (62.5) | 8 (80.0) | 16 (100.0) | 3>2>1 | |||||

| No | 7 (29.2) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (23.1) | ns | 3 (37.5) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1>2>0 | |||||

Note: HN (1) = High Negative Symptoms; HSC (2) = Higher Social Cognition; LSC (3) = Low Social Cognition GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; QLS = Quality of Life Scale.

Mean differences are significant at the 0.05 level.

Absence of criminal or substance abuse data for some of the participants.

In the second phase of analysis, a rule of thumb using the PANSS negative component and the MSCEIT was created for assigning participants to 3 subgroups corresponding to those derived by cluster analysis. To create the rule of thumb groups, we first used discriminant function analysis to determine the extent to which the original 3 cluster groups could be reproduced if classified according to only PANSS negative component and MSCEIT scores. Following confirmation of the original and predicted groupings using leave-one-out cross validation, we followed the common convention of defining cut-points as 1 SD below the mean PANSS negative component and MSCEIT scores of the 2 extreme groups representing the highest negative symptom and social cognition factor scores. Overall agreement between the K-means cluster classification and the rule of thumb classification was tested by Cohen’s Kappa coefficient within the original sample of 77 subjects. Subsequently, the rule of thumb cut-offs were applied to a holdout sample of 63 subjects and then to the samples combined (N = 140). The final 3 groups were then compared on the same dependent measures as previously.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

Demographic and clinical variables are presented in table 1. The main sample (N = 77) was composed of predominantly male, chronically ill adult patients (mean age = 43.5; SD = 10.4) with low to moderate symptoms, who were mostly treated with atypical antipsychotic medication. Table 1 also shows the descriptive statistics of negative symptom and social cognitive measures that were entered into the subsequent principal components analysis.

Principal Components Analysis of the Negative Symptom and Social Cognition Measures

Correlations among the 10 measures (table 2) show only small intercorrelations between the negative symptom measures and the social cognition measures with the exception of Hinting Task, which is significantly correlated with PANSS negative component, SANS flattening, and SANS alogia. Principal components analysis of these 10 measures converged on a 2-factor solution that accounted for 51.8% of the cumulative variance. Factor 1, named the “negative symptoms” factor, accounted for 31.3% of total variance, and included PANSS negative factor, SANS flattening/blunting, SANS alogia, SANS avolition/apathy, and SANS anhedonia/asociality. The second factor, named “social cognition” factor, represented 20.5% of total variance, and included Social Attribution Task—Multiple Choice version (SAT-MC), Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task (BLERT), Bell Object Relations Reality Testing Inventory (BORRTI) egocentricity, and MSCEIT-ME.

Table 2.

Correlations Among the Social Cognitive Measures and the Negative Symptom Measures*

| Pearson Correlation Coefficients | PANSS Negative | SANS Flattening/Blunting | SANS Alogia | SANS Avolition/Apathy | SANS Anhedonia/Asociality | SAT-MC | BLERT | Hinting | BORRTI Egocentricity | MSCEIT-ME |

| PANSS negative | 1 | |||||||||

| SANS Flattening/ blunting | 0.810** | 1 | ||||||||

| SANS alogia | 0.611** | 0.564** | 1 | |||||||

| SANS Avolition/ apathy | 0.492** | 0.401** | 0.214* | 1 | ||||||

| SANS Anhedonia/ asociality | 0.530** | 0.304* | 0.254* | 0.435** | 1 | |||||

| +SAT-MC | 0.041 | −0.104 | −0.053 | 0.076 | 0.249* | 1 | ||||

| +BLERT | 0.078 | 0.028 | −0.040 | 0.136 | −0.040 | 0.344** | 1 | |||

| +Hinting | −0.204* | −0.207* | −0.267* | −0.096 | −0.121 | 0.140 | 0.207* | 1 | ||

| BORRTTI egocentricity | −0.085 | −0.073 | 0.078 | −0.004 | .074 | −0.162 | −0.406** | 0.000 | 1 | |

| +MSCEIT-ME | −0.03 | −0.07 | 0.002 | −0.021 | −.141 | 0.298** | 0.360** | 0.222* | −0.276* | 1 |

Note: PANSS Negative, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, negative component score; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SAT-MC, Social Attribution Task—Multiple Choice, correct score; BLERT, Bell Lysaker Emotion Recognition Test, correct score; Hinting, The Hinting Task, total score; BORRTI Egocentricity, Bell Object Relations Reality Testing Inventory, Egocentricity subscale; MSCEIT-ME, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test—Managing Emotions Branch. + Higher scores represent better performance.

Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2 tailed).

Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2 tailed).

The Hinting Task, which depends heavily on verbal ability, shared loadings across the 2 factors. Therefore, this social cognition measure was removed and the analysis re-run, producing 2 well-characterized factors with no overlap, accounting for 55.1% of the cumulative variance. In this second analysis, the “negative symptoms” factor accounted for 33.1% of the total variance, and the “social cognition” factor accounted for 22.0% of the total variance (table 3). The correlation between factors was near zero (r = .000). All subsequent analyses were based on this factor solution.

Table 3.

Factor Loadings of the Social Cognition and Negative Symptom Measuresa, in a 2 Factor Solution After Varimax Rotation with Kaiser Normalization

| Component | ||

| 1 | 2 | |

| PANSS negative component | 0.923 | 0.062 |

| SANS flattening/blunting | 0.824 | −0.054 |

| SANS alogia | 0.794 | −0.034 |

| SANS avolition/apathy | 0.632 | 0.032 |

| SANS anhedonia/asociality | 0.639 | 0.024 |

| SAT-MC -score correct | 0.046 | 0.626 |

| BLERT-score correct | 0.033 | 0.815 |

| BORRTI egocentricity score | −0.017 | −0.594 |

| MSCEIT-managing emotion T-score | −0.080 | 0.754 |

After Hinting Task was removed.

K-Means Cluster

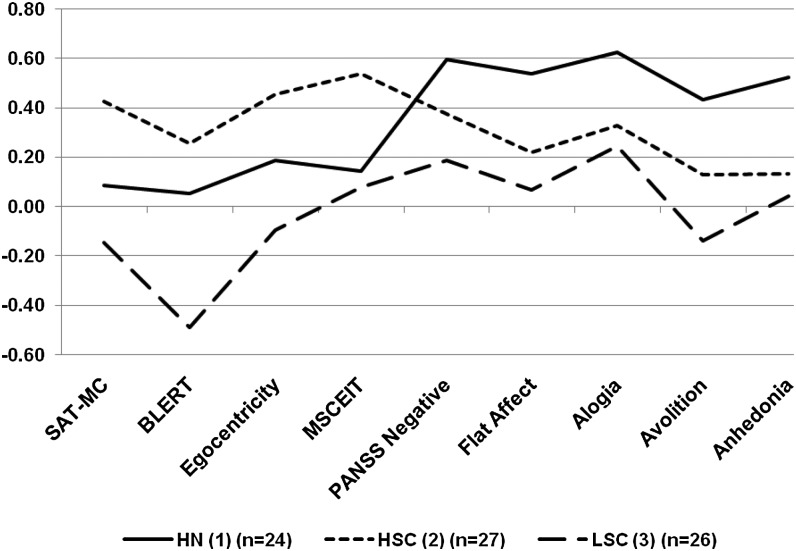

K-means cluster analysis produced 3 easily identifiable groupings that included: a high negative symptom (HN) group, a low negative symptom with higher social cognition group, and a low negative symptom group with poorer social cognition (box-plot of cluster centers is available in online supplementary material). The largest cluster (n = 27) had a cluster center at −0.64 for the negative symptoms factor and 0.79 for the social cognition factor and was labeled the higher social cognition group (HSC). The second largest cluster (n = 26) had a cluster center at −0.44 for the negative symptom factor and −1.04 for the social cognition factor and was labeled the low social cognition group (LSC). The third cluster (n = 24) had a cluster center at 1.21 for the negative symptom factor and 0.23 for the social cognition factor and was labeled HN. Figure 1 displays the standardized means on each of the negative symptom and social cognition measures for the 3 groups. A discriminant function analysis using all the measures showed 98.7% agreement with the 3-cluster solution. This was achieved based on 2 functions, 1 for negative symptoms variables (canonical correlation = 0.87, chi-square = 163.20, P < .000) and 1 for social cognition variables (canonical correlation = 0.77, chi-square = 64.10, P < .000).

Fig. 1.

Standardized social cognition and negative symptom measures by subgroups. Note: SAT-MC, Social Attribution Task-Multiple Choice; BLERT, Bell-Lysaker Emotion Recognition Task; Egocentricity, Egocentricity subscale from the Bell Object Relations Reality Testing Inventory (BORRTI); MSCEIT, Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) from the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB); PANSS negative, Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale negative component; Flat Affect, Flat Affect and blunting subscale from the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS); Alogia, Alogia subscale from the SANS; Avolition, Avolition and apathy subscale from the SANS; Anhedonia, Anhedonia and associality subscale from the SANS.

Group comparison on the negative symptom factor (F 2,74 = 79.20, P < .000) revealed significant differences between HN and both the HSC and LSC groups (P < .000), while HSC and LSC groups were statistically equivalent to each other (P = .625). Comparisons on the social cognitive factor (F 2,74 = 59.80, P < .000) indicated that all 3 groups differed significantly from each other with HSC > LSC (P < .000), HN > LSC (P < .000), and HSC > HN (P = .007).

Cross-Validation of the K-Means Cluster With the Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Following Ward’s Method

The Ward’s method analysis produced 3 easily identifiable groupings (see dendogram in online supplementary material). Agreement between the K-means method and the Ward method was considered acceptable (Kappa = 0.684).

Differences Amongst Cluster Derived Groups

Table 4 shows that HSC scored consistently higher in all the QLS subscales compared with the other 2 groups, however, only the comparison with the high negative (HN) group on the Intrapsychic subscale reached statistical significance. No differences between clusters were found in age of onset or GAF scores. HSC was found to have more participants who were ever married. LSC had more than twice the number of arrests (52.0%) than HN (29.2%) or HSC (18.5%). No significant differences were found for age of onset, number of hospitalizations, and lifetime substance abuse measures.

Rule of Thumb Creation and Concordance With Cluster Derived Groups

Based on discriminant function analysis predicting K-mean cluster assignment, we found that 87.5% of HN, 85.2% of HSC, and 80.8% of LSC could be accurately classified using only the MSCEIT and PANSS negative component scores. Overall, classification accuracy of 84.4% was achieved based on 2 functions representing PANSS negative symptoms (canonical correlation = .805, chi-square = 113.26, P < .000) and MSCEIT performance (canonical correlation = .626, chi-square = 36.60, P < .000), and these classifications were replicated at 84.4% accuracy using leave-one-out cross validation. This discriminant function analysis was also performed using the SANS total score and the MSCEIT, which classified the sample with 85.7% overall accuracy with respect to k-means derived groupings.

We defined the cut-points for a rule of thumb classification by subtracting 1 SD from the group mean of the clusters characterized by the highest negative symptom and social cognitive factor scores. This procedure established a PANSS negative factor cutoff of >19, defining higher negative symptoms, and an MSCEIT cutoff of T >37, defining higher social cognition. (In addition, a negative symptom cutoff score of > 42 for the SANS was computed using the same rule of 1 SD from the mean. Since SANS data had not been collected on the holdout sample, this cut-off score was not used in any subsequent analyses). Concordance between K-means cluster membership and the rule of thumb classification using the PANSS negative factor and MSCEIT was 84.4% (Kappa = 0.766, P < .001), the same percentage as that achieved by the discriminant function analysis.

Differences Among “Rule of Thumb” Derived Groups

The rule of thumb was applied to a holdout sample of 63 participants. The derived final subgroups (HN n = 12; HSC n = 19; LSC n = 32) were examined for differences in social functioning domains (table 4.). Although not significantly different, HSC scored higher in all QLS subscales compared with the other 2 groups. No differences were found in age of onset or GAF scores. LSC had significantly more arrests (85.7%) than HN (20%) and HSC (22.2%). LSC had higher incidence (100%) of lifetime substance abuse than HSC (80%) and HN (62.5%).

Differences Among “Rule of Thumb” Derived Groups Combined

The rule of thumb was applied to the initial cluster analysis sample and the holdout sample combined (N = 140). The derived final subgroups (HN n = 43; HSC n = 44; LSC n = 53) were examined for differences in social functioning. Table 5 shows that HSC scored consistently higher in all QLS subscales compared with the other 2 groups. HSC scored significantly higher than HN on the QLS total scale and on the QLS interpersonal and intrapsychic subscales. In addition, HSC scored significantly higher than LSC on the QLS objects/activities subscale. HSC GAF score was significantly higher than the other 2 groups. HSC had an earlier age of onset of illness than the other 2 groups. They also had more lifetime hospitalizations. HSC had a higher percentage of ever married, while LSC had more than twice the number of arrests (55.2%) than HN (26.5%) or HSC (26.5%). Finally, HN had significantly fewer members with an incidence of lifetime substance abuse (65.8%) than HSC (80.0%) and LSC (89.5%) (table 5).

Table 5.

Differences in Social Functioning for Combined Sample (N = 140) Using the “Rule- of- Thumb” Classification

| “Rule of Thumb” Derived Groups | |||||||

| HN (1) (n = 43) Mean (SD) | HSC (2) (n = 44) Mean (SD) | LSC (3) (n = 53) Mean (SD) | F/Chi square | P | Bonferroni Post hoc Comparisona | ||

| n = 139b | Age of onset | 24.0 (8.8) | 19.2 (9.4) | 24.4 (8.9) | 4.57 | .012 | 1>2; 3>2 |

| GAF | 40.9 (7.0) | 45.1 (8.9) | 41.1 (8.0) | 3.92 | .022 | 2>1; 2>3 | |

| QLS total | 46.5 (14.8) | 59.9 (20.8) | 51.9 (20.6) | 5.41 | .005 | 2>1 | |

| QLS interpersonal | 16.0 (8.3) | 22.7 (10.0) | 19.4 (9.8) | 5.47 | .005 | 2>1 | |

| QLS intrapsychic | 20.7 (6.2) | 27.2 (8.3) | 23.7 (8.8) | 7.22 | .001 | 2>1 | |

| QLS objects/activities | 7.2 (2.0) | 7.5 (2.1) | 6.2 (2.1) | 4.91 | .009 | 2>3 | |

| Count (%) | Count (%) | Count (%) | |||||

| Marital status | 7.77 | .020 | |||||

| Single | 38 (88.4) | 28 (63.6) | 36 (67.9) | 1>3>2 | |||

| Ever married | 5 (11.6) | 16 (36.4) | 17 (32.1) | 3>2>1 | |||

| n = 139b | # Lifetime hospitalizations | 8.45 | .015 | 1>3>22>3>1 | |||

| Less than 6 | 28 (65.1) | 15 (34.1) | 27 (51.9) | ||||

| 6 or more | 15 (34.9) | 29 (65.9) | 25 (48.1) | ||||

| n = 97b | # Lifetime criminal arrests | 7.35 | .025 | ||||

| 2 or less | 25 (73.5) | 25 (73.5) | 13 (44.8) | 1>3; 2>3 | |||

| More than 2 | 9 (26.5) | 9 (26.5) | 16 (55.2) | 3>1; 3>2 | |||

| n = 111b | Lifetime substance abuse | 6.36 | .041 | ||||

| Yes | 25 (65.8) | 28 (80.0) | 34 (89.5) | 3>2>1 | |||

| No | 13 (34.2) | 7 (20.0) | 4 (10.5) | 1>2>3 | |||

Note: HN (1) = High Negative; HSC (2) = Higher Social Cognition; LSC (3) = Low Social Cognition; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; QLS, Quality of Life Scale.

Mean differences are significant at the 0.05 level.

Absence of clinical, criminal or substance abuse data of some of the participants.

Discussion

This study performed a principal components analysis of 5 measures of social cognition along with measures from the 2 leading negative symptom scales and found that 4 of the 5 social cognition measures loaded on a single factor that was distinct from the negative symptom factor. The Hinting Task, the only social cognition task with substantial verbal memory and verbal expression demands,10 had a significant inverse correlation with Alogia and to a lesser extent with Blunted Affect and PANSS Negative Component, suggesting that specific negative symptoms and/or verbally mediated neurocognitive abilities may affect performance on this task, a finding also reported by Couture and colleagues.9 The SAT-MC, MSCEIT, BORRTI, and BLERT are instruments that reduce dependence on verbal expression by using multiple-choice or true-false responses. Thus, it may have been method variance (verbal expression) that was shared between negative symptoms and the Hinting Task rather than an overlap of their purported constructs.

When Hinting Task was removed, 2 factors emerged without item overlap and these produced easily interpretable cluster groupings with significant differences in functional history and concurrent community functioning as measured by the QLS. While the QLS is sensitive to the impact of negative symptoms (particularly on Intrapsychic Foundations, which includes motivation, curiosity, and sense of purpose), the differences between the cluster groups were across a number of dimensions and were not confined to just differences between the high negative and the other 2 clusters. In fact, the QLS total score was almost identical for the HN and LSC clusters, even though the LSC cluster had low negative symptoms. It was the HSC group that stood out with significantly better QLS total scores than the other 2 clusters. Thus it appears that better community functioning requires both the absence of prominent negative symptoms and better social cognition.

While QLS captures concurrent community functioning, functional histories are informative because they suggest long-standing patterns. The HSC cluster group had a significantly higher rate of ever being married than the other 2 groups, although the LSC cluster group had a higher rate of marriage than the HN cluster group. This suggests that participants in the HN cluster group have had greater difficulties in this domain of functioning since their young adulthood. On the other hand, number of arrests was greatest for the LSC cluster group with significantly higher rates of having more than 2 arrests than the other 2 cluster groups. Lifetime substance abuse was high in this entire sample, but a nonsignificant trend suggested that the LSC cluster group had higher rates than the other 2 groups.

The aim of the second phase of this study was to make these groupings practicable by attempting to establish a rule of thumb for classification that uses common schizophrenia research instruments: the PANSS and the MCCB. Having found good classification agreement between cluster membership and the groups created by the rule of thumb, we proceeded to classify 63 additional participants for whom we did not have data for the other social cognitive and negative symptom measures. We found a somewhat different distribution, with a greater proportion of participants being classified into LSC than into the other groups. Comparisons on QLS and other functional variables yielded results broadly similar to those found with the cluster groups. We then combined the holdout sample with the original sample used to produce the cluster groupings. With greater statistical power, a few additional differences were observed. Somewhat counter to expectation, compared with both other groups, the HSC group had an earlier reported age of onset and significantly more hospitalizations. We speculate that being more engaged in the social world may have led to earlier recognition of their psychiatric illness and greater use of treatment. Two trends from the cluster comparisons reached significance in the total combined sample. GAF scores were significantly better for the HSC group compared with the other 2 groups, which had nearly identical scores. Lifetime substance abuse also differed significantly with the LSC group having the highest rates and the HN group the lowest.

Thus a picture familiar to clinicians begins to emerge for the prototypical member of each group. There is the withdrawn, HN patient who avoids social interactions and also avoids getting into trouble; the low negative symptom patient with poor social judgment who is active but accomplishes little and gets into lots of trouble; and the low negative symptom patient with better social judgment who has generally better community functioning and may seek help more readily.

These findings have potential treatment significance. In an Food and Drug Administration (FDA) commentary on negative symptom trials, Laughren and Levin27 recommend that data on neurocognition (and here we include social cognition) and negative symptoms should both be collected. They state, “If it turns out that drugs having a benefit in one domain always have a similar benefit in the other domain, it becomes less attractive from a regulatory standpoint to consider them separate constructs. Perhaps, an alternative terminology could be “residual phase schizophrenia”. We believe our results support separate domains and the need for separate interventions (pharmacologic or psychosocial). All participants in this study were seeking rehabilitation, yet 3 distinct groupings were identified that had different functional histories and different community functioning. It is improbable that they all can benefit equally from the same “residual phase” treatment. Moreover, our cluster analysis suggests that subgroups may exist with differences in underlying pathology manifesting in differences along the negative and social cognition dimensions. Distinguishing rather than lumping these subgroups may shed light on different etiological processes as well as point to more specific treatments.

A few comments are warranted regarding methodological choices in this research. First, this was a post hoc study using archived data. Second, QLS was the main dependent measure of community functioning used to test differences among classification groups. While our combined sample yielded significant differences across QLS subscales, this pattern was not consistently observed when the 2 samples were examined separately. Third, while having 5 social cognition measures gave a broader measurement of the social cognition construct than most studies, some measures of social cognition were not included (eg, Ambiguous Intentions Hostility Questionnaire3). Finally, we did not include neurocognition in this analysis except for an IQ estimate. Not surprisingly, we found that IQ was lowest for the LSC group. We have previously reported on a path analysis25 showing that social cognition mediates neurocognition in predicting functioning, similar to findings reported by Couture and colleagues.9 The critical question for this analysis was the overlap of the constructs of negative symptoms and social cognition and their relationship to community functioning, and we have focused on that question narrowly.

Our results suggest that social cognition and negative symptoms are separable constructs that can be used to meaningfully classify nonacute patients. Moreover, this can be done using our rule of thumb relying on scores from the PANSS and MSCEIT. Those interested in pursuing this investigation further may be able to do so using archived data or applying this classification prospectively. It may be that in such trials, differential responses to interventions may be related to these subgroupings.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health R01 grants (MH61493 to M.D.B., KO2 MH01296 to B.E.W.); VA Rehabilitation Research and Development grants (D4752R to M.D.B., D4628W to J.M.F., D7008W to J.K.J.).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Acknowledgments

We appreciatively acknowledge the contributions of Christina Dyer, Psy.D., Lesley Schwab, BA, and Althea Morgan, MS for their assistance in the collection and management of data used in this study. In addition the authors wish to thank Ami Klin, Ph.D, for his permission to use the SAT-MC. The authors have no financial or conflict of interest to disclose. This work was performed as part of US Government service, in the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT): User's Manual. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3:97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancuso F, Horan WP, Kern RF, Green MF. Social cognition in psychosis: multidimensional structure, clinical correlates, and relationship with functional outcome. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;48:351–360. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellack AS, Sayers M, Mueser KT, Bennett M. Evaluation of social problem solving in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103:371–378. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPheeters HL. Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two southern states. Community Ment Health J. 1984;20:44–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00754103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunet-Gouet E, Achim AM, Vistoli D, Passerieux C, Hardy-Bayle MC, Jackson PL. The study of social cognition with neuroimaging methods as a means to explore future directions of deficit evaluation in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.029. doi: doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couture SM, Granholm EL, Fish SC. A path model investigation of neurocognition, theory of mind, social competence, negative symptoms and real-world functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greig TC, Bryson GJ, Bell MD. Theory of mind performance in schizophrenia: diagnostic, symptom, and neuropsychological correlates. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:12–18. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000105995.67947.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellack AS, Green MF, Cook JA, et al. Assessment of community functioning in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses: a white paper based on an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Schizophr Bull. 2006;33:805–822. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders -Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York, NY: Biometric Research Department; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opier LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–274. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Beam-Goulet JL, Milstein RM, Lindenmayer JP. Five-component model of schizophrenia: assessing the factorial invariance of the positive and negative syndrome scale. Psychiatry Res. 1994;52:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klin A. Attributing social meaning to ambiguous visual stimuli in higher-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome: the Social Attribution Task. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:831–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klin A, Jones W. Attributing social and physical meaning to ambiguous visual displays in individuals with higher-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Brain Cogn. 2006;61:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell MD, Fiszdon JM, Greig TC, Wexler BE. Social attribution test- multiple choice (SAT-MC) in schizophrenia: comparison with community sample and relationship to neurocognitive, social cognitivie and symptom measures. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heider F, Simmel M. An experimental study of apparent behavior. Am J Psychol. 1944;57:243–259. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell M, Bryson G, Lysaker P. Positive and negative affect recognition in schizophrenia: a comparison with substance abuse and normal control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1997;73:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(97)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran R, Mercer G, Frith CD. Schizophrenia, symptomatology and social inference: investigating “theory of mind” in people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1995;17:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00024-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell M. Bell Object relations and Reality Testing Inventory (BORRTI) manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S, Bell MD. BORRTI Journal Articles and Annotated Bibliography. Western Psychological Services; 2008. http://portal.wpspublish.com/portal/page?_pageid=53,70155&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL. Accessed: August 31, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell MD, Tsang HW, Greig TC, Bryson GJ. Neurocognition, social cognition, perceived social discomfort, and vocational outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:738–747. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10:388–398. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laughren T, Levin R. Food and drug administration commentary on methodological issues in negative symptom trials. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:255–256. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]