Abstract

Background: Deficits in emotion processing are thought to underlie the key negative symptoms flat affect and anhedonia observed in psychotic disorders. This study investigated emotional experience and social behavior in the realm of daily life in a sample of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, stratified by level of negative symptoms. Methods: Emotional experience and behavior of 149 patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and 143 controls were explored using the Experience Sampling Method. Results: Patients reported lower levels of positive and higher levels of negative affect compared with controls. High negative symptom patients reported similar emotional stability and capacity to generate positive affect as controls, whereas low negative symptom patients reported increased instability. All participants displayed roughly comparable emotional responses to the company of other people. However, in comparison with controls, patients showed more social withdrawal and preference to be alone while in company, particularly the high negative symptom group. Conclusions: This study revealed no evidence for a generalized hedonic deficit in patients with psychotic spectrum disorders. Lower rather than higher levels of negative symptoms were associated with a pattern of emotional processing which was different from healthy controls.

Keywords: emotions, psychosis, negative symptomatology, anhedonia, experience sampling method (ESM), daily life

Introduction

Since the time of Kraepelin and Bleuler, alterations in emotional experience and expression have been recognized to represent a core feature of schizophrenia1,2 and play a central role in 2 prominent negative symptoms of schizophrenia: flat affect and anhedonia. Flat affect reflects a deficit in the “expression” of emotions, and anhedonia (defined as diminished ability to experience positive emotions from pleasant events) represents a deficit in the “experience” of emotions. Studies consistently demonstrate alterations in outward emotional expression in schizophrenia patients.3,4 Study findings on emotional experience, however, are more heterogeneous. Patients with schizophrenia report higher levels of anhedonia compared with healthy individuals on self-report scales, such as the Chapman Anhedonia Scales.5,6 Furthermore, trained interviewers evaluating patients using standardized clinical measures report that patients show high levels of anhedonia.7 Emotion induction studies, however, fairly consistently show no difference between schizophrenia patients and healthy participants in their reports of positive emotional experience to emotionally charged stimuli.3,8 Naturalistic studies, employing the Experience Sampling Method (ESM), showed that patients experience more negative and less positive emotions compared with healthy controls.9

One possible explanation for these paradoxical findings is the difference between anticipatory pleasure (related to future activities) and consummatory (in-the-moment) pleasure. Patients with schizophrenia are shown to have greater deficits in anticipatory pleasure than in consummatory pleasure, suggesting a deficit in anticipating that events will be pleasurable but not in experiencing pleasure once the enjoyable stimulus is present.10 Alternatively, patients might have difficulties to distinguish an overall lower mood or a low frequency of pleasant events from problems generating positive emotions from experienced pleasurable events.11 Therefore, they might report anhedonia on self-report questionnaires, whereas they actually are in an overall low mood or experience very few positive events but do still enjoy these events when they are present. Furthermore, the comparability of studies is hampered by the great variety of stimuli and considerable psychopathological heterogeneity in samples of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia.12

In order to gain knowledge on the emotional experience and (social) hedonic capacities “in-the-moment” in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders, the current study investigates a large sample of patients using the ESM.13 ESM is a structured self-assessment technique in which participants are prompted at random intervals throughout the day to report about their current experiences. This method allows investigating emotional experience and behavior in the moment, in the context of the normal daily life of patients without making a strong appeal to their memory. ESM has previously been used in several studies investigating psychosis, mostly focusing on positive psychotic symptoms or emotional and psychotic reactivity to daily life stress (for a review see14). The few ESM studies investigating negative symptoms, showed that flattened emotional expression is not reflected in reduced emotional experience in daily life9 and that (healthy) participants scoring high on social anhedonia15 or psychosis proneness16 differ from nonpsychosis-prone individuals in their emotional reaction to social situations.

The current study aimed to extend these findings by focusing on 3 aspects of emotional experience and behavior related to negative symptoms of psychosis spectrum disorders: (1) General emotional experience, defined as the intensity and intraindividual instability of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), which is similar to what has been done in Myin-Germeys and colleagues9 but the current sample is much larger; (2) Hedonic capacity operationalized as the ability to generate positive emotions after pleasurable events17; (3) Social hedonic capacity: the capacity to enjoy social situations, which has been tested in general population samples15,16 but never in patients. Analyses were performed in a large sample of healthy controls and patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. We divided the patients in 2 groups based on the presence of general (primarily expression-based) negative symptoms.

We hypothesize patients to report higher NA intensity and instability and lower PA intensity and instability compared with controls,9 with no significant differences between high and low negative symptom patients. Patients with high levels of negative symptoms are expected to generate less positive emotions after pleasant and social events compared with controls and low negative symptoms patients. We have no specific hypotheses on the difference between low negative symptom patients and controls.

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 149 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (n = 134) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 15) and 143 healthy controls. Data for the current study were pooled from 3 previous ESM studies focusing on stress reactivity in daily life18,19 and paranoia.20 None of the data was previously used to study emotional experience in relation to negative symptoms. ESM questionnaires were set up identically in terms of mood and context in order to enable pooling of the data. Inclusion criteria were aged 18–65 years and sufficient command of the Dutch language to understand the questionnaires. Exclusion criteria were brain disease and a history of head injury with loss of consciousness. Controls were excluded if presenting with a lifetime history of psychotic or affective disorder and a family-history of psychotic disorder. Patients (both inpatients and outpatients) were recruited from mental health facilities in the South of the Netherlands and in Flanders, Belgium. Controls were recruited from the general population in the same regions through random mailings. Interview data and clinical record data were used to complete the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness18,20 or the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History.19,21 Written informed consent, confirming to local ethics committee guidelines, was obtained from all participants. Participants were compensated with a voucher of 25 Euro (or equivalent).

Experience Sampling Method

Daily life data were collected using ESM, of which feasibility, validity, and reliability have been demonstrated in a wide range of populations.13,14 Participants received a preprogrammed digital wristwatch and assessment forms collated in a booklet for each day. Ten times a day on 6 consecutive days, the watch emitted a signal at unpredictable moments between 7.30 AM and 10.30 PM. After each “beep,” participants reported affect, symptoms and context. The ESM procedure was explained in a briefing session and all participants completed a practice form in order to confirm that they understood the procedure. Participants were instructed to complete their reports immediately after the beep and to register the time at which they completed the questionnaire. Reports were assumed valid when participants responded to the beep within 15 minutes.22 Participants were only included in the analyses, when they provided valid responses for at least one-third of the emitted beeps.22 The following variables were derived from the ESM questionnaires:

General Emotional Experience

Emotional experience was investigated using measures of (1) emotional intensity and (2) emotional instability. Emotional experience was assessed with 8 emotion adjectives (eg, “I feel anxious”) rated on 7-point Likert scales (1 “not at all” to 7 “very”). The items “insecure,” “lonely,” “anxious,” “sad,” and “guilty” constituted NA(Cronbach’s α = .81). The items “cheerful,” “relaxed,” and “satisfied” constituted PA(Cronbach’s α = .82). PA and NA intensity were defined as the mean score on PA and NA. Emotional instability was defined using the mean square successive difference, which is the average of the squared difference between successive observations. This measure is suggested by several authors as a measure of affective (in)stability in momentary assessment studies.23,24

Hedonic Capacity

Participants reported the most important event that happened between the current and the previous beep and subsequently rated this event on a 7-point bipolar scale (−3 “very unpleasant,” 0 “neutral,” and 3 “very pleasant”), providing a subjective measure of event pleasantness. Observations including events rated as a bit pleasant (1), pleasant (2), and very pleasant (3) were included in the analyses because anhedonia is by definition related to pleasant events. Neutral events were set as the reference category.17 Anhedonia was defined as diminished positive emotion experience after pleasant events, operationalized as the change in PA after pleasant events compared with the change in PA after neutral events.

Social Hedonic Capacity

At each beep, participants reported whether or not they were alone. If not, they reported how much they preferred to be alone on a 7-point Likert scale (1 “not at all” to 7 “very much”). Social anhedonia was defined as diminished positive emotion experience in the company of others, operationalized as the change in PA when with others compared with when alone.25 We also analyzed change in NA when with others compared with when alone, in order to examine the possible negative effects of social company on emotional experience. In addition, 2 other measures related to social anhedonia were modeled: (1) time spent alone and (2) preference to be alone while in the company of others.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Interview-based information on symptom severity was assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),26 which rates positive, negative, and general symptomatology with a reference period of 2 weeks. Each item was scored on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 “absent” to 7 “extreme”. Assessment was done by a trained research assistant within a week after the sampling period. PANSS negative symptom score was based on the sum score of 6 PANSS items (blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, passive/apathetic withdrawal, lack of spontaneity, and motor retardation). Internal consistency of this negative symptom score was high (Cronbach’s α = .90). Two items from the original PANSS negative symptoms subscale (difficulty in abstract thinking and stereotyped thinking) were not included in this negative symptom score, and one item from the original PANSS general symptoms subscale (motor retardation) was included. Prior factor analyses on the PANSS yield inconsistent results, but the majority of studies include these items in their negative symptom scale, sometimes supplemented with items such as active social avoidance and poor attention.27–29

The assumption of normality of the negative symptom score was violated (KS(292) = 0.32, P < .001) with Skewness of 2.61 (SE = 0.14) and Kurtosis of 7.40 (SE = 0.28). Since no nonparametric tests for multilevel analyses are present, we divided the patient group in 2 based on their negative symptom score: a high negative symptom group with a negative symptom score ≥3 (mild) on at least 2 of the PANSS negative symptom items and a low negative symptom group consisting of the remaining participants.

Data Analyses

Multilevel linear modeling techniques are a variant of the unilevel linear regression analyses and are ideally suited for ESM data analysis consisting of multiple observations in one person, creating 2 levels of analysis (ESM-beep level and subject level). Data were analyzed with both the multilevel XTREG module and the unilevel REG module in STATA.30 Effects from predictors in the multilevel model were expressed as B, representing the fixed regression coefficient. In all analyses, we investigated the effect of diagnostic group (0 “controls”; 1 “patients”) and negative symptom group (0 “controls”; 1 “low negative symptom patients”; 2 “high negative symptom patients”) on the dependent variable. Sex and age were included as possible confounders in all analyses. Furthermore, we performed all analyses both with and without controlling for level of depression (PANSS item G6) because depression level differed significantly over the groups and negative symptoms and depression are strongly correlated.31

General Emotional Experience

In order to investigate general differences in emotional experience, multilevel random regression analyses were conducted with emotional intensity and instability as dependent variables and diagnostic group and negative symptom group as the independent variables.

Hedonic Capacity

In order to study hedonic capacity, regression analyses were conducted comparing differences in number of positive events in daily life as a function of diagnostic group and negative symptom group. To investigate the effect of event pleasantness on PA level, a multilevel random regression analysis was conducted with PA as dependent variable and event pleasantness, diagnostic group, and the interaction between event pleasantness and diagnostic group as independent variables. These analyses were repeated with negative symptom group as independent variable. NA intensity was included in the model because NA and PA correlate weakly to moderately with each other.32 Number of observations was also included, taking into account possible systematic differences in event appraisal through, for example, personality differences. From these models, the effect of event pleasantness, stratified by group, was calculated by applying and testing the linear combinations using the STATA LINCOM command. Main effects and interactions were assessed by Wald tests.

Social Hedonic Capacity

Social hedonic capacity was investigated fitting multilevel random regression models with PA as dependent variable and diagnostic group, social context (0 “not alone”; 1 “alone”) as well as their interaction as independent variables. The effect of company on NA was investigated in a similar way fitting multilevel random regression models with NA as dependent variable. The analyses were repeated for negative symptom group. Time spent alone was investigated using a linear regression analysis with number of moments alone (per participant) as dependent variable and diagnostic group and negative symptom group as independent variables. Preference to be alone was investigated using multilevel random regression analyses with score on the item “preference to be alone” as dependent variable and diagnostic group and negative symptom group as independent variables.

Sex Differences

Since the distribution of sex differed over groups and might influence our results, we first analyzed the moderating effect of sex and decided to add sex as a confounder in all our analyses.

Results

Sample

Of the 334 participants who entered the study, 31 participants were excluded from the analyses because they did not meet the diagnostic inclusion criteria, 12 (9 patients and 3 controls) because of insufficient number of valid ESM observations (<20) and 9 because of missing PANSS data. The final sample therefore comprised 149 patients and 143 controls. Additional information regarding sociodemographic characteristics and ESM reports is summarized in table 1. Scores on the dependent and independent variables are presented in table 2. The low negative symptom group consisted of 100 patients and the high negative symptom group of 49 patients. The patient groups did not significantly differ from each other on age, diagnosis, education, work situation, and PANSS positive symptom score. Patient groups, however, differed on all other PANSS subscales, sex, marital status, and number of valid beeps (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Sample Characteristics

| Low Negative Symptom Patients | High Negative Symptom Patients | Controls | High vs Low | |

| n | 100 | 49 | 143 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 33.2 (10.7) | 34.3 (10.5) | 37.0 (11.7) | F 1,289 = 0.29, P = .59 |

| Male (%) | 64 | 81 | 39 | χ2(1) = 4.85, P = .03 |

| Diagnosis (%)a | χ2(1) = 0.38, P = .54 | |||

| Schizophrenia | 91 | 43 | 0 | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 9 | 6 | 0 | |

| Symptomatology | ||||

| PANSS total (SD) | 50.4 (13.6) | 63.7 (15.4) | 32.4 (3.5) | F 1,289 = 53.24, P < .001 |

| PANSS positive (SD) | 14.4 (6.4) | 14.9 (6.5) | 7.5 (1.0) | F 1,289 = 0.34, P = .56 |

| PANSS general (SD) | 27.0 (7.1) | 31.9 (8.0) | 17.7 (2.3) | F 1,289 = 26.01, P < .001 |

| PANSS negative (SD) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.8) | 1.2 (0.5) | F 1,289 = 477.81, P < .001 |

| PANSS depression (SD) | 7.3 (1.7) | 16.4 (5.2) | 6.1 (0.7) | F 1,289 = 7.38, P = .007 |

| Education (%)a | χ2(2) = 3.90, P = .14 | |||

| Elementary school | 5 | 14 | 2 | |

| Secondary school | 79 | 76 | 45 | |

| Higher education | 14 | 10 | 52 | |

| Marital status (%)a | χ2(3) = 8.14, P = .04 | |||

| Married/living together | 19 | 4 | 71 | |

| Divorced | 10 | 14 | 6 | |

| Widowed | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Never married | 70 | 80 | 22 | |

| Work situation (%)a | χ2(3) = 5.25, P = .15 | |||

| Working/studying | 19 | 6 | 94 | |

| Protected work | 4 | 6 | 0 | |

| Incapable of work | 65 | 71 | 2 | |

| Unemployed | 10 | 16 | 2 | |

| Retired | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mean n valid reports (%) | 42 (70) | 38 (63) | 48 (80) | F 1,289 = 3.89, P = .05 |

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Due to rounding, percentages may not add exactly to 100%.

Table 2.

ESM Variables

| Low Negative Symptom Group (mean, SD) | High Negative Symptom Group (mean, SD) | Controls (mean, SD) | |

| NA | 1.8 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.3) |

| NA instability | 20.5 (22.0) | 18.2 (27.1) | 9.0 (12.9) |

| PA | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.3 (1.2) | 5.3 (0.7) |

| PA instability | 49.0 (43.6) | 32.6 (28.1) | 32.0 (27.2) |

| Number of pleasant events | 34.2 (10.1) | 30.8 (10.1) | 40.2 (9.0) |

| Alone (% time spent) | 41 | 46 | 36 |

Note: ESM, Experience Sampling Method; PA, positive affect; NA, negative affect.

General Emotional Experience

Patients reported significantly lower PA intensity (B = −0.76, 95% CI = −0.97 to −0.54, P < .001) and higher NA intensity (B = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.46–0.75, P < .001) compared with controls. Analyses on the patient groups showed that both patient groups reported significantly lower PA intensity compared with controls and differed significantly from each other, with high negative symptom patients reporting the lowest PA intensity (table 3). Both patient groups also reported higher NA but did not differ significantly from each other (table 3). Controlling for depression did not change any of the significance levels.

Table 3.

Emotional Intensity and Instability

| Low Negative Symptom Patients | High Negative Symptom Patients | High vs Low | |

| Ba (95% CI) | Ba (95% CI) | ||

| Intensity | |||

| PA | −0.60 (−0.83 to −0.38)*** | −1.09 (−1.4 to −0.81)*** | F 1,289 = 4.54* |

| NA | 0.55 (0.39–0.71)*** | .72 (0.52–0.92)*** | F1,289 = 3.07 |

| Instability | |||

| PA | 14.43 (5.1–23.7)** | −3.00 (−15.2–9.15) | F 1,284 = 8.83** |

| NA | 4.80 (0.04–9.6)* | 1.40 (−4.7–7.6) | F 1,284 = 1.35 |

Note: PA, positive affect; NA, negative affect.

aRegression coefficient indicates the difference in emotional intensity and instability in the patient groups compared with controls. Sex and age included in the model.

*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

PA (B = 9.70, 95% CI = 0.82–18.59; P = .03) but not NA (B = 3.88, 95% CI = −0.62–8.37, P = .09) was significantly more instable in patients compared with controls. Analyses on the negative symptom groups revealed that low negative symptom patient’s PA was more instable compared with controls and high negative symptom patients (table 3). High negative symptom patients did not display this higher PA instability. Low negative symptom patient’s NA was significantly more instable compared with controls but not compared with high negative symptom patients. The latter group did not differ significantly from controls on NA instability. After including depression in the model, the results on PA instability remained similar, whereas the difference between low negative symptom patients and controls on NA instability became trend-significant (B = 4.79, 95% CI = −0.22–9.80, P = .06).

Hedonic Capacity

Patients reported significantly fewer positive events compared with controls (B = −7.18, 95% CI = −9.5 to −4.9, P < .001), this was true for both patient groups (low: B = −6.06, 95% CI = −8.6 to −3.5, P < .001; high: B = −9.46, 95% CI = −12.7 to −6.2, P < .001) and patient groups differed from each other at a trend level (χ2(1) = 3.91, P = .05). No group differences on number of reported negative or neutral events were found. The main effect of event pleasantness on PA was significant (B = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.08–0.11, P < .001), indicating that increasing event pleasantness was associated with higher PA. No significant interaction effect between event pleasantness and diagnostic group (χ2(3) = 1.69, P = .64) in the model of PA was found, indicating that the patient group as a whole did not differ from controls in the effect of event pleasantness on PA. Controlling for depression level did not change the significance of the interaction (χ2(3) = 1.79, P = .62).

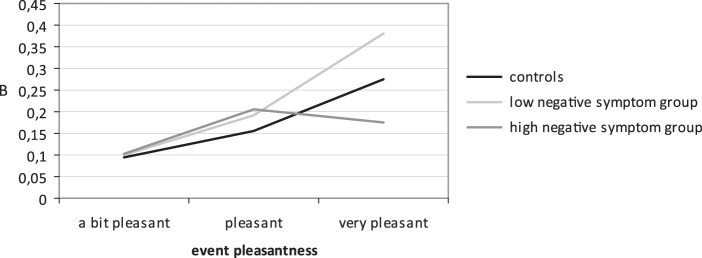

The interaction between negative symptom group and event pleasantness was significant (χ2(6) = 13.80, P = .03), indicating that the patient groups differed from each other in their PA reaction after pleasant events (see figure 1). Calculating effects stratified by group revealed that low negative symptom patients reacted with more PA to pleasant events compared with controls and high negative symptom patients (low: B = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.10–0.16, P < .001; high: B = 0.07, 95% CI = 0.03–0.11, P = .001; controls: B = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.07–0.10, P < .001). Again, controlling for depression did not change the significance of the interaction effect (χ2(3) = 13.60, P = .03).

Fig. 1.

Association between event pleasantness and PA (stratified by group and controlled for NA level and number of positive events in the negative symptom groups).

Social Hedonic Capacity

Compared to controls, patients were less often in the company of others (B = −0.06, 95% CI = −0.10 to −0.01, P = .02), specifically high negative symptom patients (B = −0.09, 95% CI = −0.15 to −0.02, P = .01) but not low negative symptom patients (B = −0.04, 95% CI = −0.10–0.01, P = .10). When in the company of others, patients displayed more preference to be alone compared to controls (B = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.32–0.82, P < .001), and this was true for both patient groups (low: B = 0.47, 95% CI = 0.20–0.74, P = .001; high: B = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.45–1.1, P < .001), which did not differ significantly from each other (χ2(1) = 3.35, P = .07).

The main effects of social company on PA (B = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.09–0.16, P < .001) and NA (B = −0.06, 95% CI = −0.88 to −0.04, P < .001) were significant, showing an overall PA increase and NA decrease when with others compared with when alone. No significant interaction effect between social company and diagnostic group in the model of PA was found (B = −0.01, 95% CI = −0.08–0.06, P = .76), whereas a significant effect in the model of NA was found (B = −0.08, 95% CI = −0.12–0.04, P < .001).

Analyses on the negative symptom groups showed a significant interaction effect between negative symptom group and social company in the model of NA (χ2(2) = 16.46, P < .001) but not in the model of PA (χ2(2) = 2.41, P = .30). Further analyses indicated that the NA decrease when with others compared with when alone is larger in the low negative symptom group than in controls (χ2(1) = 16.44, P < .001). The differences between patient groups and between the high negative symptom group and controls were not significant.

Sex Differences

All our analyses were repeated with sex as a moderator (interacting with negative symptom group). The only significant interaction effect between negative symptom group and sex was found in the model of NA instability (F 2,282 = 10.46, P < .001).

Discussion

Negative symptoms were common in this large sample of patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Approximately one-third of patients reported at least 2 negative symptoms. We found no general deficit in the ability to experience emotions, whether positive or negative, in the patient sample. Patients, however, reported less PA and more NA compared with controls but did not exhibit decreased NA and PA instability compared with controls. Thus, patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder exhibited differences in levels of emotion experienced but not in the moment-to-moment variability of these emotions. However, consideration of the negative symptoms severity revealed that patients with less severe negative symptoms reported more PA instability compared with both patients with more severe negative symptoms and controls. Negative symptom level did not influence NA levels or instability.

Second, we found that lower PA levels did not necessarily reflect a hedonic deficit because patients reported equal (in the high negative symptom group) or larger (in the low negative symptom group) PA increases in reaction to pleasant events compared with controls. Nevertheless, patients reported less pleasant events in their daily life. Thus, both patient groups experienced pleasant emotions in response to pleasant events even though they reported fewer pleasant events compared with controls.

Finally, we investigated the social component of hedonic capacity and showed that patients were more often alone and more often preferred to be alone while with others compared with controls. Time spent alone was significantly related to negative symptom level, whereas preference to be alone was not. Being with others was associated with PA increase and NA decrease in both controls and patients, with largest effects in low negative symptom patients.

This study, therefore, suggests no specific deficits in the experience of emotions in general. Low negative symptom patients, however, might be more reactive to their environment and differences between patients and controls are expressed at the behavioral level since they report less pleasant events and are more often alone.

General Emotional Deficit or Anhedonia?

Higher NA levels in patients are in line with previous ESM and laboratory studies showing that patients experience more frequent and intense negative emotions compared to controls.8,9 In addition to the higher NA levels, patients reported lower PA levels in daily life, being in line with an earlier ESM study of our group.9 The decreased PA level could either reflect diminished hedonic capacity or merely result from less pleasurable life circumstances. Patients indeed reported less pleasant events compared with controls. However, when a positive event was reported, patients generated an equal or even greater (in the low negative symptom group) amount of PA in response to self-reported pleasurable events. These results suggest that schizophrenia patients do not suffer from hedonic deficits when processing positive events “in the moment” in daily life but do experience fewer of them. These results are in line with a recent meta-analysis of laboratory studies on emotional experience in schizophrenia8 and an ESM study showing intact consummatory pleasure in patients.10 This may have important implications for patients’ daily life dynamics because they may be less likely to seek out opportunities to engage in activities when their ability to anticipate, which potentially rewarding experiences will be enjoyable, is impaired.

Social Anhedonia

We subsequently investigated whether deficits in hedonic capacities are specifically expressed in social contexts. Social company was related to PA increases and NA decreases in all participants, but patients spent more time alone compared with controls and showed more preference for solitude. This social withdrawal may be occasioned by poor anticipatory coupling of affect and behavior, similar to the findings with regard to pleasurable events and the greater preference for solitude may indicate a lack of relatedness or need to belong.33 Interestingly, preference of solitude in our study was not related to negative symptom level. It is unlikely that the observed social withdrawal is caused by social anxiety or other negative emotions because NA decreased in all groups when in company of other people. These results on social behavior and emotional experience give a hint on the complexity of the processes involved in the social life of patients. The shown behavioral withdrawal of patients and their higher preference for solitude when in company suggest that problems or deficits in the social area are present. Their preference for solitude while experiencing the positive effect of social company on their emotions is striking and requires further investigation. The current analyses are limited in the conclusions that can be drawn with regard to the specific nature of the social interactions. This would also be an interesting topic for follow-up studies.

Negative Symptom Level

The analyses on the 2 patients groups based on negative symptom level showed overall rather similar results. Low negative symptom patients, however, differed more often from controls in their reaction pattern compared with high negative symptom patients. Low negative symptom patients showed increased emotional instability and higher emotional reactivity to pleasurable events compared with controls, whereas high negative symptom patients did not display a different pattern of emotional reactivity. These findings extend previous reports showing increased emotional reactivity to negative events, particularly in patients with increased levels of positive symptoms and decreased levels of negative symptoms34,35 and challenge current ideas of emotional experience in relationship to level of negative symptoms because not high but low level of negative symptom levels were associated with a pattern of emotional reactivity that differed from healthy controls. Furthermore, these results plead for a careful and differentiated interpretation of study results on emotional experience in patients within the heterogeneous schizophrenia syndrome and suggest that self-report assessment instruments allowing capturing both the experienced emotions as well as the context in which they occur may allow a more refined insight in the nature of negative symptoms compared with current clinician-rated assessment scales.

Methodological Issues

Several methodological issues should be taken into account. First, participants had to comply with a paper-and-pencil diary protocol. Some authors questioned the reliability and subject compliance in paper-and-pencil ESM studies, favoring the use of electronic devices. In a comparative study, Green and colleagues36, however, concluded that both methods yielded similar results. A study by our group also showed the validity of the paper-and-pencil data37 and in a pilot-study, we observed that backfilling (per day or week) did take more time and, moreover, was experienced as being more dreadful than performing the study according to the standard protocol. In the current study, participant’s compliance with the ESM protocol is checked several times. Furthermore, participants reported the time after answering the questions and we only included reports within a 20-minutes time window. In order to cheat, participants needed to realize the reason for timing and write down all random timings. Second, although the PANSS is a standard measure of negative symptoms, it has been increasingly criticized because the negative symptom items are all entirely based on behavioral observation and reports of clinicians and family members and might not directly reflect the underlying (emotional) deficit in patients’ experience. Unfortunately, the 2 items which are more experiential in nature “emotional withdrawal” and “passive apathetic withdrawal” are also observational items based on reports of others and interpersonal behavior during the interview. Third, the small subgroup of patients with schizoaffective disorder could have influenced the results. Therefore, we reconducted all analyses excluding them. This did not significantly change the results. Fourth, sex differences between our groups were present. The high negative symptom group consisted of a higher percentage of men than the low negative symptom group. Therefore, we added sex as a possible confounder in all our analyses. Analyses on the moderating effect of sex show that including sex as a covariate in the analyses is sufficient because sex only significantly impacted on emotional instability. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate this in more depth, in accordance to an earlier study investigating sex differences in stress reactivity.38

Funding

Prof. Dr I.M.-G. was supported by a 2006 NARSAD Young Investigator Award and by the Dutch Medical Research Council (VIDI grant).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dr Ann Kring for her thoughtful comments on the manuscript. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1.Bleuler E. Dementia Praecox, or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraeplin E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburgh, UK: Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kring AM, Moran EK. Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:819–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremeau F. A review of emotion deficits in schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:59–70. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.1/ftremeau. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanchard JJ, Mueser KT, Bellack AS. Anhedonia, positive and negative affect, and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:413–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen AS, Dinzeo TJ, Nienow TM, Smith DA, Singer B, Docherty NM. Diminished emotionality and social functioning in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193:796–802. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188973.09809.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earnst KS, Kring AM. Construct validity of negative symptoms: an empirical and conceptual review. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17:167–189. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(96)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul PA, deVries MW. Schizophrenia patients are more emotionally active than is assumed based on their behavior. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:847–854. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen AS, Docherty NM, Nienow T, Dinzeo T. Self-reported stress and the deficit syndrome of schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2003;66:308–316. doi: 10.1521/psyc.66.4.308.25440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myin-Germeys I, Oorschot M, Collip D, Lataster J, Delespaul P, van Os J. Experience sampling research in psychopathology: opening the black box of daily life. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1533–1547. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oorschot M, Kwapil T, Delespaul P, Myin-Germeys I. Momentary assessment research in psychosis. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:498–505. doi: 10.1037/a0017077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husky MM, Grondin OS, Swendsen JD. The relation between social behavior and negative affect in psychosis-prone individuals: an experience sampling investigation. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown LH, Silvia PJ, Myin-Germeys I, Kwapil TR. When the need to belong goes wrong: the expression of social anhedonia and social anxiety in daily life. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:778–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wichers M, Aguilera M, Kenis G, et al. The catechol-O-methyl transferase Val158Met polymorphism and experience of reward in the flow of daily life. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3030–3036. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myin-Germeys I, Nicolson NA, Delespaul PA. The context of delusional experiences in the daily life of patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2001;31:489–498. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lataster T, Collip D, Lardinois M, Van Os J, Myin-Germeys I. Evidence for a familial correlation between increased reactivity stress and positive psychotic symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thewissen V, Bentall RP, Lecomte T, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I. Fluctuations in self-esteem and paranoia in the context of daily life. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:143–153. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andreasen N, Flaum M, Arndt S. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:615–623. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080023004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delespaul P, editor. Assessing Schizophrenia in Daily Life. The Experience Sampling Method. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Maastricht University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebner-Priemer UW, Eid M, Kleindienst N, Stabenow S, Trull TJ. Analytic strategies for understanding affective (in)stability and other dynamic processes in psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:195–202. doi: 10.1037/a0014868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jahng S, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychol Methods. 2008;13:354–375. doi: 10.1037/a0014173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwapil TR, Silvia PJ, Myin-Germeys I, Anderson AJ, Coates SA, Brown LH. The social world of the socially anhedonic: exploring the daily ecology of asociality. J Res Pers. 2009;43:103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine SZ, Rabinowitz J. Revisiting the 5 dimensions of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:431–436. doi: 10.1097/jcp/.0b013e31814cfabd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lykouras L, Oulis P, Psarros K, et al. Five-factor model of schizophrenic psychopathology: how valid is it? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;250:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s004060070041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Oord EJ, Rujescu D, Robles JR, et al. Factor structure and external validity of the PANSS revisited. Schizophr Res. 2006;82:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software; Release 9.2. Texas: College Station: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winograd-Gurvich C, Fitzgerald PB, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Bradshaw JL, White OB. Negative symptoms: a review of schizophrenia, melancholic depression and Parkinson's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wichers MC, Myin-Germeys I, Jacobs N, et al. Evidence that moment-to-moment variation in positive emotions buffer genetic risk for depression: a momentary assessment twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konstantareas MM, Hewitt T. Autistic disorder and schizophrenia: diagnostic overlaps. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:19–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1005605528309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lataster T, Wichers M, Jacobs N, et al. Does reactivity to stress cosegregate with subclinical psychosis? A general population twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green AS, Rafaeli E, Bolger N, Shrout PE, Reis HT. Paper or plastic? Data equivalence in paper and electronic diaries. Psychol Methods. 2006;11:87–105. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobs N, Nicolson NA, Derom C, Delespaul P, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I. Electronic monitoring of salivary cortisol sampling compliance in daily life. Life Sci. 2005;76:2431–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myin-Germeys I, Krabbendam L, Delespaul PA, van Os J. Sex differences in emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:805–809. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]