Abstract

Objective: To carry out an up-to-date comprehensive survey of the content and quality of intervention trials relevant to the treatment of people with schizophrenia. Design: Data were extracted and analyzed from 10 000 trials on the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register. Main outcome measures: Source, type and date of publication, country of origin, language, size of trial, interventions, and outcome measures. Results: In the last decade, there has been a great increase in the number of trials relevant to schizophrenia and an improvement in the accessibility to reports. The number of trials per year is rising (currently ∼600/year) with China now producing 25% of the annual total. The number of reports of trials is increasing at an even greater rate due to multiple publications. Drug trials still dominate (83%) although an increasing proportion of studies are now evaluating psychological therapies (21%). Trials remain small (median 60 people) and often employ new nonvalidated outcomes scales (2194 different scales were employed with every fifth trial introducing a new rating instrument). Conclusions: A more collaborative, pragmatic, and patient-centered approach is necessary to produce larger schizophrenia trials. Wider consultation and careful consideration of all relevant perspectives would result in trials with greater clinical utility and direct value to people with the illness and their families or carers.

Keywords: randomized, survey, quality

Introduction

Over 60 years ago, a study evaluating the effects of streptomycin for tuberculosis, the Medical Research Council (MRC) Streptomycin Trial,1 marked the advent of randomized controlled trials. In psychiatry, the publishing of this landmark study coincided with the development of drug treatments for schizophrenia,2 and the subspecialty quickly adopted the new evaluative technique to highlight differences between treatments. Over 10 years ago, in a special issue commemorating the 50th anniversary of the MRC trial, the British Medical Journal published a survey of intervention studies relevant to the care of people with schizophrenia identified up to that time.3 In the last decade, however, there has been a great increase in research activity, sources of studies, searching skills, and sophistication of dissemination. There is now an opportunity for a much more representative investigation of trial activity in this field. The aim of this study is to provide an up-to-date comprehensive survey of the content and quality of intervention studies relevant to the treatment of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychosis.

Methods

Inclusion criteria: every report on the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Register of the first 10 000 trials (November 2008).

This register is now constructed from regular searches of 71 electronic databases and 247 conference proceedings.4 It is maintained in a Microsoft Access Database and constitutes a unique record of published and unpublished randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (parallel group comparative studies in which allocation of treatment is not explicitly stated to be random) relevant to the care of people with schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychosis. Full text hard copies are obtained of every relevant record and are used to reliably code each study. Data are extracted on source, type and date of publication, country of origin, language, size of trial, interventions, and outcome measures. Where indicated by Cochrane reviewers or the report, records are merged into one that represents a whole trial rather than single publication. Most reports were coded at the Christian Medical Center, Vellore, India, and a 10% sample is rechecked to ensure high reliability. The coding of basic report data into the register has been shown to be reliable.3 Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and polynomial regression undertaken in “R.”

Results and Discussion

The register in November 2008 held 12 211 reports of 10 000 trials. In 1998, when the first survey was done, the register held only 2000 trials.3 This was most probably an underestimate. Because searching methods and accessibility to reports and trials related to schizophrenia has greatly improved in the last decade, our current survey is likely to be much more accurate.

Most of the 12 211 reports were fully published in journals (9460, 77%), a further 1280 (10%) were presented at conferences, while the remainder were available as letters, book chapters, or remained unpublished. Although the proportion of reports found in leading general medical journals seems to be increasing over time (table 1), it remains small considering the medical and societal impact of the illness. The underrepresentation of schizophrenia in these important journals may reflect the poor quality of the research, low confidence of researchers, or/and the lack of emphasis given to the condition by journal editors. Furthermore, most schizophrenia trials are not found on the widely used database, PubMed, with only 3476 (28%) of all reports being available. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) within the Cochrane Library (http://www.thecochranelibrary.com) is a much more comprehensive source of trials but each Cochrane Group’s register remains the definitive resource (http://szg.cochrane.org/cochrane-schizophrenia-group-specialised-register).

Table 1.

Schizophrenia Reports Published in Leading General Medical Journals

| Publications | 1948–1998 | 1999–2008 |

| BMJ | 21 | 21 |

| Lancet | 33 | 14 |

| JAMA | 6 | 11 |

| NEJM | 2 | 9 |

Ninety three percent (9292) of the 10 000 trials focused on the treatment of schizophrenia or other nonaffective psychosis. Most of the remainder either focused on the care of people with poorly defined serious mental illness or on the carers of people with schizophrenia.

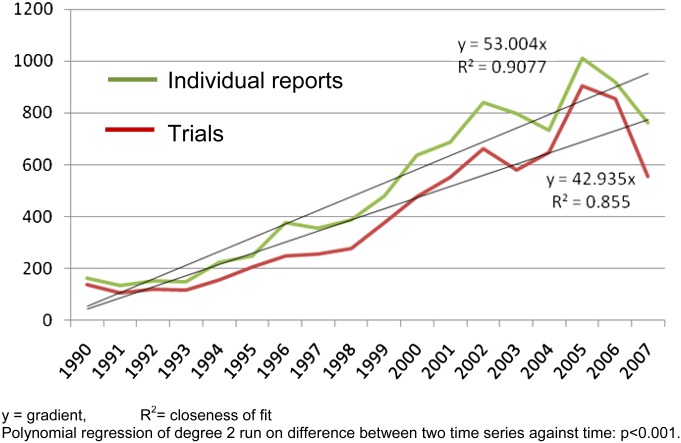

The number of trials per year relevant to schizophrenia is still rising from about 35 in the 1950s and 1960s, 100 in 1970s and 1980s, 200 in 1990s to 650 per year so far in the 2000s. (The dip in the period 2007–2008 is an artifact of delay in indexing of most databases.) The number of “reports” published per trial is also rising steadily. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was, with some exceptions, one report per trial. Increasingly, the same trial often produces multiple reports, as illustrated by the significant divergence of the lines in figure 1. We identified one trial that has been published 122 times in full articles. We have not named this study as making it a scapegoat could allow our subspecialty to forget that responsibility for this situation is collective. Being published 30 or 40 times is currently reasonably common. Although one article may be the protocol, another the economic data and yet another the 5-year follow up, multiple articles often simply repeat findings in a different format. We accept that duplicate or triplicate publication may be reasonable dissemination of an important trial or justified to present complex data sets. However, there are a number of problems associated with multiple publications. Firstly, it makes it difficult to identify, which reports originate from which trial as, sadly, unique trial identifiers remain rare. Secondly, multiple publications serve only to confuse—often giving the impression that there are more data than there really are.5 This can be used as a marketing tool to highlight favorable findings of a treatment and hide disadvantageous facts amidst the confusion. One of the limitations of this study is that we have not reliably extracted data on source of funding of trials to be able to establish a link between multiple publications and pharmaceutical marketing. Thirdly, some practices associated with multiple publications are clearly corrupt and challenge the integrity of medical research.5 Examples include the fact that journals have a financial incentive to publish because reprint fees can be a rich source of income or the use of ghostwriters to ensure that company-supported work is reproduced again and again.

Fig. 1.

Number of trials and number of reports across time

Most (9202, 75%) of the reports were published in English but an increasing proportion are in Mandarin (2164, 18%).

Overall, 32% (3181) of trials were carried out in North America and 26% (2620) in Europe with the UK being the country generating the most trials in this region (1060). A recent phenomenon has been a burgeoning of work from China—the output of which has increased at a faster rate than that from any other country. Before 1998, there had only been 216 Chinese trials. In the last decade, this number has multiplied 10-fold so that currently 22% (2161) of trials in the database come from China. We know that a country’s Gross Domestic Product predicts productivity of schizophrenia trials6; this burgeoning of activity in China is therefore likely to continue and should be followed by much more work from countries like India and Brazil. However, Chinese researchers have highlighted the often poor methodological quality associated with their compatriots’ trials.7 Nonetheless, should quality control in this field follow patterns seen in the Chinese electronics and plastics industries,8 we can confidently expect that China will rapidly move toward mass production of high quality studies. At present, even if fewer than 10% of Chinese trials are of good quality, as suggested by existing research,7 this would still represent a considerable number of high-grade trials per annum.

The average number of trial participants rose from 65 people in 1998 to 132 in 2008. Although we now have a larger register, both averages are probably overestimates. As discussed above, larger trials tend to produce multiple publications and are, despite every effort, at greater risk of being counted several times. Although there are notable exceptions of some large high-impact studies, the median and mode estimates of study size of 60 participants indicate that schizophrenia trials remain tiny. For an outcome such as “clinically important improvement in mental state” to show a 20% difference between groups a study would have to have around 150 participants in each arm (α = .05, power 85%).3 With the number of researchers growing and the culture of collaborative work remaining rare, many studies remain far too small to demonstrate even moderate treatment effects.

The 10 000 trials evaluated 1940 different interventions. Table 2 shows the number and percentage of trials evaluating different types of intervention. Drugs remain the most common intervention with a marked increase in the study of risperidone. This is possibly attributable to risperidone becoming the benchmark control medication over haloperidol. The proportion of trials evaluating psychological therapies and policies or care packages has also increased.

Table 2.

Interventions and Outcomes

| Number (%) | ||

| 1948–1998 | 1948–2008 | |

| Interventions | ||

| Drugs | 1725 (86) | 8298 (83) |

| Haloperidol | 708 | 1386 |

| Risperidone | 137 | 1555 |

| Psychological therapies | 164 (8) | 2060 (21) |

| Policies or care packages | 172 (9) | 1538 (15) |

| Physical treatments (eg, ECT, light therapy) | 77 (4) | 584 (6) |

| Other (eg, singing) | 37 (2) | 810 (8) |

| Outcome scales | ||

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale | 800 (40) | 2813 (28) |

| Positive and Negative Symptom Scale for Schizophrenia | 67 (3) | 2240 (22) |

| Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms | 113 (6) | 808 (8) |

Most trials (7317, 73%) used at least one rating scale to measure outcomes. Overall, 2194 different instruments were employed (every fifth trial thus introducing a new rating scale) with Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale, and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms remaining the most popular choices (table 2). One thousand nine hundred and ninety-six scales were used 10 times or less with 1142 scales being used only once. Although the trial-to-new-scale ratio has declined, we get no impression that it is as a result of exhaustion of the subspecialty to invent and reinvent new scales. Six hundred and eighty-four trials employed more than 5 measures but greater numbers were not uncommon with one trial listing 36 different outcome scales. The sheer number of different scales makes the clinical interpretation of results very difficult and significantly contributes to the confusion mentioned above. Scales are mainly research tools, generated by researchers with limited, often obscure, meaning for people with schizophrenia, their families, and clinicians. Furthermore, up to 40% of these scales may not be clearly validated and are therefore likely to produce exaggerated estimates of treatment effect.9

There is hope that the next decade will see an increased effort in psychiatry to develop and apply agreed standardized sets of outcomes in clinical trials that would be of genuine value to all those interested in the results of evaluative studies. Such approach would follow the example of established initiatives like OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology)10 and more recently COMET (Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials)11.

Conclusions

There has been an increase in the rate of production of trials in schizophrenia over the last decade, with the emergence of China as an important contributor. On average, size remains small, multiple publications ever more common, and the invention of new outcomes scales prevalent. Lone committed researchers remain the norm. There are, however, some rare but important examples of moves toward a more collaborative, pragmatic, and patient-centered approach in schizophrenia trials. This is the way forward, working together, with wide consultation and careful consideration of all relevant perspectives in order to design large studies that serve at least some needs of all those involved.

Funding

Support for this research was not sought specifically. The register of schizophrenia trials is maintained though support for Cochrane Editorial Base from the Department of Health, England. J.M. is funded to undertake part-time research as part of psychiatry training by Nottinghamshire Healthcare Trust. C.E.A. is funded by University of Nottingham, UK.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Bert Park for help with polynomial regression. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure. pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) J.M. and C.E.A. have support from no company for the submitted work; (2) J.M. and C.E.A. have no relationships with any company that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work; and (4) J.M. and C.E.A. have no nonfinancial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. J.M. helped data extract, clean data, formulate the questions to be asked of the data, undertake the analysis, and write and revise the article. C.E.A. helped data collect, construct the database, clean data, formulate the questions to be asked of the data, undertake the analysis, and write and revise the article. For this research, we did not require ethics approval.

References

- 1.Medical Research Council. Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Br Med J. 1948;2:769–782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner T. Chlorpromazine: unlocking psychosis. BMJ. (Clinical research ed). 2007;334(suppl 1):s7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thornley B, Adams C. Content and quality of 2000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 50 years. BMJ. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1181. (Clinical research ed). 1998;317:1181–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochrane Schizophrenia Group. Cochrane schizophrenia group specialised register. 2010 http://szg.cochrane.org/cochrane-schizophrenia-group-specialised-register. Accessed June 1, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huston P, Moher D. Redundancy, disaggregation, and the integrity of medical research. Lancet. 1996;347:1024–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moll C, Gessler U, Bartsch S, El-Sayeh HG, Fenton M, Adams CE. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and productivity of schizophrenia trials: an ecological study. BMC Psychiatry. 2003;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang D, Yin P, Freemantle N, Jordan R, Zhong N, Cheng KK. An assessment of the quality of randomised controlled trials conducted in China. Trials. 2008;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng J, Liu X, Bigsten A. Efficiency, technical progress, and best practice in Chinese state enterprises (1980-1994) J Comp Econ. 2003;31:134–152. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall M, Lockwood A, Bradley C, Adams C, Joy C, Fenton M. Unpublished rating scales: a major source of bias in randomised controlled trials of treatments for schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:249–252. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tugwell P, Boers M. OMERACT conference on outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: introduction. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:528–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson P. COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000041. http://www.comet-initiative.org/. Accessed January 16, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]