Abstract

Background

It is well known that genetic alternation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) plays critical roles in tumorgenesis of lung cancer and can predict outcome of non-small-cell lung cancer treatment, especially the EGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) therapy. However, it is unclear whether epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation involve in the response to the EGFR-TKI therapy.

Methods

Tumor samples from 155 patients with stages IIIB to IV NSCLC who received EGFR-TKI therapy were analyzed for DNA methylation status of Wnt antagonist genes, including SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5, DKK3, WIF1, and APC, using methylation specific PCR (MSP) method. EGFR mutations detections were performed in the same tissues samples using Denaturing High Performance Liquid Chromatography (DHPLC).

Results

We found that Wnt antagonists tend to methylate simultaneously. Methylation of sFRP1 and sFRP5 are reversely correlated with EGFR mutation (P = 0.005, P = 0.011). However, no correlations of methylations of other Wnt antagonist genes with EGFR mutation were found. The patients with methylated SFRP5 have a significant shorter progression free survival than those with unmethylated SFRP5 in response to EGFR-TKI treatment (P = 0.002), which is independent of EGFR genotype.

Conclusions

Patients with unmethylated SFRP5 are more likely to benefit from EGFR-TKI therapy.

Keywords: DNA methylation, EGFR-TKI, Wnt antagonists, Non-small cell lung cancer

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. NSCLC is the most common form of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 85% of lung cancer cases [2,3]. The efficacy of traditional chemotherapy has reached a plateau [4-6]. Therefore, new approaches are needed to improve the efficacy of lung cancer therapy. A number of targeted anticancer agents have been recently developed and approved for clinical use, among which the EGFR-TKI has been used as the first-line therapy for lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations [7-11].

EGFR gene product functions as a receptor tyrosine kinase that affects cell proliferation and survival by activating downstream signaling pathways. In 2004, three research groups reported that mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR can predict the responses to TKIs in NSCLC patients [12-14], which enables the identification of patient populations that are more likely to benefit from TKI therapies and serves as the first step toward personalizing lung cancer therapy. However, according to the theory of “EGFR addition”, which refers to the dependency of cancer cells on EGFR mutation to maintain their malignant phenotypes [15], lung cancer patients harboring mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of their EGFR genes should survive much longer, in response to the EGFR-TKI therapy, than the actual result. This suggested that EGFR mutation cannot explain all clinical outcomes of TKI therapy. At least 10 ~ 20% of patients with wild-type EGFR still significantly benefit from EGFR-TKI treatment, whereas around 10% of patients with mutated EGFR are resistant to the TKI therapy [10,16,17]. In addition, previous studies reported that both T790M mutation [18] and c-MET amplification [19] involved in acquired resistance of EGFR-TKI therapy. Therefore, factors in addition to EGFR genotype may also contribute to the response to EGFR-TKI therapy.

The Wingless-type (Wnt) signaling cascade is an important regulator of embryonic development [20]. Activation of Wnt signaling pathway leads to elevated expression of ß-catenin in cytoplasm, which in turn translocates to the nucleus, interacts with T cell factor/lymphocyte enhancer factor family, induces, downstream target genes that regulate cell proliferation and cancer progression. Aberrant activation of Wnt signaling pathway has been found in a number of tumors [21], which can be categorized into the following three common forms: 1) mutations in APC and/or Axin; 2) aberrant activation of Wnt signaling induced by activated EGFR[22]; 3) methylation of Wnt antagonists. Mutations of APC and/or Axin are rarely found in lung cancer patients. In addition, EGFR-TKI treatment blocks activation of EGFR in patients. Therefore, we hypothesized that the methylation of Wnt antagonists might significantly affect the responses to the EGFR-TKI therapy in NSCLC patients. Suzuki et al [23] analyzed the synchronous effects and correlations between Wnt antagonists and EGFR mutations and found that EGFR mutation was correlated with a good prognosis in tumors without methylated wnt antagonist genes.

In current study, we analyzed the methylation status of the CpG sites within Wnt antagonist genes, including SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5, WIF1, DKK3, APC, and CDH1, in 155 Chinese patients who received EGFR-TKI therapy and investigated potential clinical implication of the epigenetic regulation of Wnt antagonists.

Methods

Patients

155 patients were enrolled in current study. They were pathologically diagnosed as stage IIIB or IV NSCLC, with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance (ECOG) status of 0 to 2; and received EGFR-TKI as either first- or second-line therapy at the Peking University Cancer Hospital between June 2006 and December 2009. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Beijing Cancer Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The smoking status of patients was decided during their first visit. A smoker was defined as the one who smoked more than 100 cigarettes in his/her life time. Patients were treated with either TKI therapy or platinum-based chemotherapy as the first line of treatment until their disease progressed, justified by imaging evidence or aggravated symptoms. The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [24] including progressive disease (PD), stable disease (SD), partial remission (PR) and complete remission (CR) was used to evaluate the drug response after patients received treatment every 6 weeks to 2 months. The objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the sum of PR and CR, while the disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the sum of SD, PR, and CR. Progression-free survival(PFS) was assessed from the beginning of therapy to disease progress or death from any cause. Overall survival(OS) was assessed from the beginning of first-line therapy until death from any cause.

DNA extraction and methylation-specific PCR

Genomic DNA of tumor tissues from patients biopsied before TKI treatment were extracted using QIAmp FFPE DNA kit (Qiagen). The methylation status of the CpG sites within the gene loci of SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5, WIF1, DKK3, APC, and CDH1 was decided by MSP assays as described previously [25-27]. Briefly, genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite, followed by PCR amplifications using the primer pairs that can specific detect either the methylated or the unmethylated CpG sites. Genes were defined as methylated if the PCR products could be detected using the methylated DNA-specific primer pairs, while they were defined as unmethylated if the PCR products could only be detected using the unmethylated DNA-specific primer pairs. DNA from the human adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelial cell lines, A549 and A549/DDP, was used as the positive control for methylated DNA, while DNA from lymphocytes of healthy nonsmoking volunteers was used as the negative control. The methylation status results were confirmed by at least one repeat of the methylation-specific PCR assays. The following primers were used:

sFRP1:MethylatedF:5’-GTTTTCGGAGTTAGTGTCGCGC-3’,R:5’-ACGATCGAAAACGACGCGAACG-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-GTAGTTTTTGGAGTTAGTGTTGTGT-3’,R:5’-ACCTACAATCAAAAACAACACAAACA-3’;sFRP2:MethylatedF:5’-TCGGAGTTTTTCGGAGTTGCGC-3’,R:5’-GCTCTCTTCGCTAAATACGACTCG-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-GGTTGGAGTTTTTTGGAGTTGTGT-3’,R:5-CCCACTCTCTTCACTAAATACAACTCA-3’;sFRP5:MethylatedF:5’-TGGCGTTGGGCGGGACGTTC-3’,R:5’-AACCCGAACCTCGCCGTACG-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-TGGTGTTGGGTGGGATGTTTG-3’,R:5’-CAACCCAAACCTCACCATACAC-3’;DKK3MethylatedF:5’-GGGGCGGGCGGCGGGGC-3’,R:5’-ACATCTCCGCTCTACGCCCG-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-TTAGGGGTGGGTGGTGGGGT-3’,R:5’-CTACATCTCCACTCTACACCCA-3’;WIF-1MethylatedF:5’-CGTTTTATTGGGCGTATCGT-3’,R:5’-ACTAACGCGAACGAAATACGA-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-GGGTGTTTTATTGGGTGTATTGT-3’,R:5’-AAAAACTAACACAAACAAAATACAAAC-3’;APCMethylatedF:5’-TATTGCGGAGTGCGGGTC-3’,R:5’-TCGACGAACTCCCGACGA-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-GTGTTTTATTGTGGAGTGTGGGTT-3’,R:5’-CCAATCAACAAACTCCCAACAA-3’;CDH-1MethylatedF:5’-TGTAGTTACGTATTTATTTTTAGTGGCGTC-3’,R:5’-CGAATACGATCGAATCGAACCG-3’,UnmethylatedF:5’-TGGTTGTAGTTATGTATTTGTTTTTAGTGG-3’,R:5’-ACACCAAATACAATCAAATCAAACCAAA-3’.

Mutation detection

The denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) was used to detect mutations in the exon 19 and 21 of EGFR tyrosine kinase domains as described previously [28].

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 16.0). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess the association between DNA methylation and EGFR genotypes. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox proportional hazard regression model. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine the overall survival and progression-free survival curves. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study patients

Table 1 summarized the demographic characteristics of 155 study patients, among which 118 cases were adenocarcinoma and 37 cases were non- adenocarcinoma (29 squamous carcinoma, 5 large cell carcinoma, and 3 adeno- squamous carcinoma cases). 60 of all patients received EGFR-TKI as the first-line therapy, while the rest had EGFR-TKI as the second- or more-line treatment. Among those 95 patients who had EGFR-TKI as the second- or more-line treatment, 63 patients took platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line treatment. The median follow-up time for all patients was 22.4 months (from 2.4 to 77.2 months).

Table 1.

Methylation and mutation profile of NSCLC

|

Clinical characteristics (cases) |

Methylation (%) |

EGFR mutation (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|||||||||

| SFRP1 | SFRP2 | SFRP5 | DKK3 | WIF1 | APC | CDH1 | Any gene | ||

|

Gender |

|||||||||

| Male (74) |

30 (40.5) |

20 (27.0) |

9 (12.2) |

9 (12.2) |

3 (4.1) |

13 (17.6) |

7 (9.5) |

44 (59.5) |

36 (48.6) |

| Female (81) |

31 (38.3) |

20 (24.7) |

14 (17.3) |

13 (16.0) |

3 (3.7) |

18 (22.2) |

8 (9.9) |

48 (59.3) |

49 (60.5) |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| <65 (89) |

33 (37.1) |

21 (23.6) |

10 (11.2) |

12 (13.5) |

3 (3.4) |

16 (18.0) |

7 (7.9) |

48 (53.9) |

56 (62.9)* |

| ≥65 (66) |

28 (42.4) |

19 (28.8) |

13 (19.7) |

10 (15.2) |

3 (4.5) |

15 (22.7) |

8 (12.1) |

44 (66.7) |

29 (43.9) |

|

Smoking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Never (93) |

35 (37.6) |

24 (25.8) |

14 (15.1) |

15 (16.1) |

2 (2.2) |

21 (22.6) |

8 (8.6) |

58 (62.4) |

57 (61.3)* |

| Smokers (62) |

26 (41.9) |

16 (25.8) |

9 (14.5) |

7 (11.3) |

4 (6.5) |

10 (16.1) |

7 (11.3) |

34 (54.8) |

28 (45.2) |

|

Histology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Adenocarcinoma (118) |

46 (38.9) |

30 (25.4) |

16 (13.6) |

16 (13.6) |

4 (3.4) |

21 (17.8) |

14 (11.9) |

72 (61.0) |

65 (55.1) |

| Non-adenocarcinoma (37) |

15 (40.5) |

10 (27.0) |

7 (18.9) |

6 (16.2) |

2 (5.4) |

7 (18.9) |

1 (2.7) |

20 (54.1) |

20 (54.1) |

| Total | 61 (39.4) | 40 (25.8) | 23 (14.8) | 22 (14.2) | 6 (38.7) | 31 (20%) | 15 (9.7%) | 92 (59.4%) | 85 (54.8%) |

*The frequency of this group is significantly higher than their counterparts.

Epigenotype of Wnt antagonists in NSCLC

Genomic DNA was extracted from tumor tissues of all patients as described in the Method Section. The methylation status of Wnt antagonist genes including SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5, WIF1, DKK3, APC, and CDH1, defined as their epigenotype, was detected by Methylation Specific PCR Assays (examples were shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1A). The frequency of methylation events in Wnt antagonist genes in patients with different demographic characteristics was listed in Table 1. Interestingly, no significant difference in epigenotype of Wnt antagonist genes was found between male and female, among different age groups, between smokers and non-smokers, or between adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma cases.

Using DHPLC, we also detected EGFR activating mutations in exon 19 or 21 (the examples of wild type, mutated exon 19, and mutated exon 21 were shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1B, 1C, and 1D). Among the 155 patients, 85 (55.4%) carried mutations in either exon 19 or 21 of the EGFR genes (Table 1).Similar to the previous studies, we found that EGFR mutation rates were significantly increased among the patients younger than 65 years old (P = 0.02, Fisher’s exact test) and the patients who are nonsmokers (P = 0.04, Fisher’s exact test). EGFR mutation reversely correlates with sFPR1 methylation (P = 0.005) and sFRP5 (P = 0.011). We fail to find methylation of other wnt antagonist genes correlated with EGFR mutation (Table 2).

Table 2.

P value among methylated genes and EGFR mutation

| sFRP1 | sFRP2 | sFRP5 | DKK3 | WIF-1 | APC | CDH-1 | EGFR mutation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sFRP1 |

NA |

0.004 |

0.005 |

0.008 |

0.02 |

<0.0001 |

0.266 |

0.005 |

| sFRP2 |

0.004 |

NA |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.007 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.854 |

| sFRP5 |

0.005 |

<0.0001 |

NA |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.06 |

<0.0001 |

0.011 |

| DKK3 |

0.008 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

NA |

0.0001 |

0.006 |

<0.0001 |

0.489 |

| WIF-1 |

0.02 |

0.007 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

NA |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.094 |

| APC |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.06 |

0.006 |

0.03 |

NA |

0.126 |

0.546 |

| CDH-1 |

0.266 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

0.02 |

0.126 |

NA |

0.592 |

| EGFR |

0.005 |

0.854 |

0.011 |

0.489 |

0.094 |

0.546 |

0.592 |

NA |

| mutation |

We next investigated whether the epigenotype of any Wnt antagonist genes correlated with the genotype of EGFR. Hierarchical clustering of the epigenotype of SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5, WIF1, DKK3, APC, and CDH1, as well as the genotype of EGFR (defined as “1” if mutation was detected in the exon 19 or 21, and as “0” if no mutation was detected) was generated using Partek Genomics Suite 6.5 (Partek Inc., MO). As shown in Figure 1, the epigenotype of Wnt antagonist genes had similar patterns, which were different from the genotype of EGFR. Therefore, our results suggested that the DNA methylation of Wnt antagonist might be independently regulated from the genotype of EGFR.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering of Wnt antagonist DNA methylation status and EGFR genotype in 155 patients received EGFR-TKI therapy. Red represents methylated gene or mutated EGFR, while blue represents unmethylated gene or wild-type EGFR, The figure of hierarchical clustering showed that the epigenotype of Wnt antagonist genes had similar patterns, which were different from the genotype of EGFR.

Epigenotype of Wnt antagonist genes and clinical responses to TKI therapy

The RECIST was used to evaluate the clinical response of all patients to the TKI therapy. By the end of our study, 59 (38.1%), 53 (33.2%), 43 (27.7%) patients were defined with PD, SD, or PR, respectively. We then calculated the ORR and DCR and analyzed the difference between patient groups with different demographic characteristics, as well as with different genotypes of EGFR and epigenotypes of Wnt antagonist genes. As shown in Table 3, when only single factor was considered, the histology of the cancer (adenocarcinoma/nonadenocarcinoma), line treatment of TKI therapy (first line/not- first line), as well as smoking status (smoker/nonsmoker) significantly affected the ORR to the TKI therapy. Similarly, the gender (male/female), the histology of the cancer (adenocarcinoma/nonadenocarcinoma) as well as smo-king status (smoker/nonsmoker) were found to significantly affect the DCR of the TKI therapy. However, when all demographic characteristics were considered, only the histology of the cancer (P = 0.006, 95% CI, 1.712-26.057, multivariate logistic regression) was associated with ORR.

Table 3.

Multivariate statistic of gender, age, histology, smoking status, treat line, EGFR mutation and SFRP5 methylation for objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR)

| Variable |

Objective response rate (ORR) |

Disease control rate (DCR) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||

| P value | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|

Gender (male / female) |

0.188 |

0.881 |

0.926 (0.337-2.542) |

0.001 |

0.115 |

2.117 (0.834-5.734) |

|

Age (≤65 / >65) |

0.351 |

0.078 |

2.295 (0.912-5.772) |

0.291 |

0.791 |

1.110 (0.515-2.393) |

|

Histology (adenocarcinoma / nonadenocarcinoma) |

0.002 |

0.006 |

6.680 (1.712-26.057) |

0.049 |

0.244 |

1.663 (0.707-3.915) |

|

Line Treatment (first line / not-first line) |

0.016 |

0.078 |

2.184 (0.917-5.200) |

0.940 |

0.491 |

0.756 (0.341-1.678) |

|

Smoking Status (smoker / nonsmoker) |

0.016 |

0.262 |

0.526 (0.171-1.617) |

0.001 |

0.188 |

0.524 (0.200-1.371) |

|

EGFR Mutation (wide type / mutation) |

<0.0001 |

<0.0001 |

7.695 (2.895-20.454) |

<0.0001 |

0.002 |

3.255 (1.540-6.881) |

| SFRP5 Methylation (methylated / unmethylated) | 0.222 | 0.650 | 0.734 (0.193-2.788) | 0.04 | 0.106 | 0.434 (0.158-1.193) |

Previous studies have indicated that EGFR mutation significantly affected the ORR and DCR of the TKI therapy. Consistently, we found that the genotype of EGFR significantly affected the ORR (P < 0.0001, 95% CI, 2.895-20.454, multivariate logistic regression adjusted by gender, age, histology, line treatment, and smoking status) and the DCR (P = 0.002, 95% CI, 1.540-6.881, multivariate logistic regression adjusted by gender, age, histology, line treatment, and smoking status) (Table 3). Our results confirmed the higher response rate to the TKI therapy among patients with EGFR mutations as compared to the patients with wild-type EGFR.

Next, we investigated whether epigenotype of Wnt antagonists correlated with the clinical responses rate of the TKI therapy. Our univariate analysis identified the epigenotype of SFRP5 as the only potential factor significantly affecting DCR but not ORR (P = 0.04). However, the positive association of SFRP5 with DCR was not confirmed in multivariate analysis. When we sub-grouped patients based on their demographic characteristics, we found that SFRP1 methylation significantly reduced DCR in patients older than 65 (P = 0.038) and sFRP5 methylation significantly reduced DCR in patients suffered adenocarcinoma (P = 0.042).

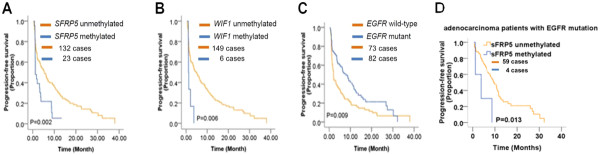

Epigenotype of Wnt antagonists and progression-free survival (PFS)

We next analyzed whether the epigenotypes of Wnt antagonists could predict the PFS in response to the TKI therapy. The median PFS time in all patients was 5.1 months (ranging from 0.4 month to 38 months). Interestingly, as shown in Figure 2A, patients with methylated SFRP5 gene had significantly shorter median PFS time (1.2 months, 95% CI, 0.5-1.9) as compared to those with unmethylated SFRP5 gene (6.1 months, 95% CI, 4.4-7.8) (P = 0.002, Logrank Test). Similarly, patients with methylated WIF1 gene had significantly shorter median PFS time (1.1 months, 95% CI, 95% CI, 1.0-1.2) as compared to those with unmethylated WIF1 gene (5.4 months, 95% CI, 3.5-7.4) (P = 0.006, Logrank Test) (Figure 2B). We did not find association between epigenotype of other Wnt antagonists and PFS in response to the TKI therapy (Additional file 1: Figure S2 A-F). Moreover, after adjusted by age, gender, histology of the cancer, smoking status, and line of treatment, the methylation of SFRP5 gene was still significantly associated with a shorter PFS (P = 0.008; harzard ratio, 2.165, 95% CI, 1.2-3.8; Cox proportional hazards models of survival analysis), while the methylation of WIF1 gene was no longer associated with a shorter PFS (P = 0.224; hazard ratio, 1.804, 95% CI, 0.7-4.7; Cox proportional hazards models of survival analysis) (Table 4). Taken together, our results suggested that the methylation status of SFRP5 might be able to predict the PFS in response to the TKI therapy.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves are shown comparing the progression free survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP5 (A), WIF1 (B), different genotype of EGFR (C), or SFRP5 in adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutation group (D).

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis of gender, age, histology, smoking status, EGFR mutation, WIF1 methylation and SFRP5 methylation for progression-free survival (PFS)

| Variable | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

Smoking Status |

0.986 |

1.004 |

| (smokers/nonsmokers) |

|

(0.615-1.640) |

|

Histology |

0.689 |

0.915 |

| (adenocarcinoma/Nonadenocarcinoma) |

|

(0.592-1.414) |

|

Gender |

0.006 |

0.516 |

| (male/female) |

|

(0.322-0.826) |

|

Age |

0.456 |

0.858 |

| (<65/>65) |

|

(0.575-1.282) |

|

Lines of Treatment |

0.302 |

0.807 |

| (first line/non-first line) |

|

(0.537-1.213) |

|

EGFR Mutation |

0.024 |

0.656 |

| (mutation/wide type) |

|

(0.455-0.945) |

|

SFRP5 Methylation |

0.008 |

2.165 |

| (methylated/unmethylated) |

|

(1.226-3.823) |

|

WIF1 Methylation |

0.224 |

1.804 |

| (methylated/unmethylated) | (0.697-4.674) |

Similar to the previous discovery [27], we also found that the median PFS time for patients with EGFR mutations (8.3 months, 95% CI, 5.5-11.1) was significantly longer than the median PFS for patients with wide-type EGFR (2.0 months, 95% CI, 1.5-2.5) (P = 0.009, Logrank test) (Figure 2C). This is still valid when tested by Cox proportional hazards model of survival analysis (P = 0.024; hazard ratio, 0.656, 95% CI, 0.5-0.9; adjusted by age, gender, smoking status, histology of the cancer, and line of treatment). More interestingly, we found that in the subgroup of patients with adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutation, the ones with methylated SFRP5 had a significantly shorter PFS (2.0 months), as compared to the ones with unmethylated SFRP5 (9.0 months) (P = 0.013, Logrank Test) (Figure 2D).

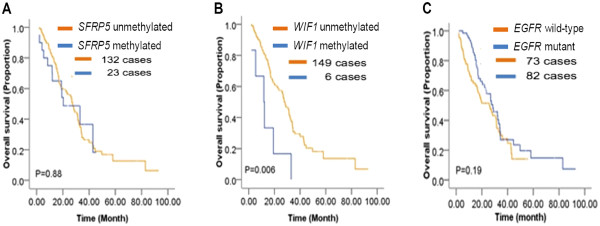

Epigenotype of Wnt antagonists and overall survival rate (OS)

To test whether the epigenotype of Wnt antagonists can predict the clinical outcome of the TKI therapy, we first investigated the association of DNA methylation of the Wnt antagonists and overall survival rate in our patient cohort. Nine patients (6.5%) were lost during the follow-up period of our study. The median OS time was 27.4 months (ranging from 3.0 to 93.1 months). Interestingly, patients with methylated WIF1 genes had significantly reduced overall survival time (P = 0.006, Logrank Test) (Figure 3B), while the epigenotypes of SFRP5 (Figure 3A), SFRP1, SFRP2, DKK3, APC, and CDH1 (Additional file 1: Figure S3 A-E), as well as the genotype of EGFR (Figure 3C) were not associated with OS in our patients.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves are shown comparing the overall survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP5 (A), WIF1 (B), or different genotype of EGFR (C).

Correlation between Wnt antagonist methylation and Progression-free survival in platinum-based chemotherapy

In order to decide if WIF-1 and sFRP5 are TKIs specific biomarkers related to PFS of TKIs treatment, we meanwhile analyzed the association of chemotherapy with the epigenotype of Wnt antagonists in 63 patients out of the whole group, who once took platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment. We failed to find significant differences in PFS between patients with or without sFRP5 methylation (3.2 ms, 95% CI 2.01-4.5 vs 4.3 ms, 95% CI 2.5-6.2, respectively, P = 0.487). We did not find differences in PFS between patients with or without WIF-1 methylation (3.2 ms, 95% CI 1.89-4.67 vs 2.0 ms, 95% CI 1.71-2.36 P = 0.798) either. We accidentally found discrepancy in PFS between patients with or without sFRP1 methylation (1.8 ms,95% CI, 1.50-2.09 vs 3.0 ms 95% CI, 1.9-4.0, P = 0.017). However, this statistically significant difference in PFS remains limited for patients in clinical practice.

Discussion

Recent studies have demonstrated that cancer is as much an epigenetic disease as it is a genetic disease (Iacobuzio-Donahue). Therefore, in addition to genetic alterations, changes in epigenetic features such as CpG DNA methylation status of specific gene loci also mark the progress of cancers. Our current study showed that methylation of Wnt antagonist SFRP5 gene before treatment, independent of the genotype of EGFR gene, correlated with decreased progression free survival rate in NSCLC patients in response to the EGFR-TKI therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report indicating that DNA methylation at specific gene loci in patient may predict drug response to the EGFT-TKI therapy.

Both genetic and epigenetic risk factors for NSCLC have been studied extensively. Suzuki et al [23] has reported that methylation of the Wnt antagonist DKK3 correlated with low survival rate in NSCLC patients, despite of the different therapies patients received. However, in our study, we did not find significant difference in the EGFR-TKI responses between patient groups with or without methylated DKK3 (Additional file 1: Figure S2 and S3). In contrast, our results suggested epigenotype of SFRP5 provide better prognostic estimation for the EGFR-TKI response, comparing to other Wnt antagonists.

SFRP5 is a member of the SFRP protein family containing a cysteine-rich domain homologous to the putative Wnt-binding site of Frizzled proteins. It acts as soluble antagonist of Wnt signaling and is highly expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium, and moderately expressed in the pancreas ("Entrez Gene: SFRP5 secreted frizzled-related protein 5"). Previous studies has identified association of SFRP5 promoter hypermethylation with Acute myeloid leukemia [29], ovarian cancer [30], gastric cancer [31], oral squamous cell carcinoma [32], pancreatic cancer [33] and breast cancer [34].

We found that hypermethylation of SFRP5 predicted worse outcomes of the EGFR-TKI therapy. Therefore, SFRP5 DNA methylation status may serve as a prognostic molecular marker for appropriately predicting whether NSCLC patients would benefit from the EGFR-TKI therapy. Especially, it is interesting that in the subgroup with adenocarcinoma and EGFR mutation, patients with sFRP5 methylation have a significantly shorter PFS than those without sFRP5 methylation, While in nonsmokers without EGFR mutation, patients without sFRP1 methylation have a longer PFS compared with patients with its methylation(9.7 ms vs 2.0 ms, p = 0.05). Based on these results, we can make a hypothesis that activation of Wnt signaling by antagonist methylation could confer tumors the characters of stem cell, which consequently causes tumors resistant to EGFR TKIs therapy by generating acquired resistance, such as MET amplification or changes of PTEN tumor suppressor activity and so on. Further study is needed to validate this hypothesis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study revealed that sFRP5 may be an independent factor affecting PFS during long time maintenance of TKIs therapy. Furthermore, the simple, PCR-based detection method of DNA methylation may be more feasible as clinical tests, compared to protein or RNA expression detection in clinics. Both general DNA methylation inhibitors and Wnt-pathway-targeting anticancer drugs are under development [35,36]. Our results that linked Wnt antagonist hypermethylation and EGFR-TKI response suggest that the treatment paradigm combining epigenetic drugs and EGFR-TKI may be a potential and attractive therapeutic option for patients with NSCLC.

Abbreviations

EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; EGFR-TKI: Epidermal growth factor receptor -tyrosine kinase inhibitors; MSP: Methylation specific PCR; Wnt: Wingless-type; ECOG: Eastern cooperative oncology group; ORR: Objective response rate; DCR: Disease control rate; PFS: Progression-free survival; OS: Overall survival; PD: Disease progression; CR: Complete response; PR: Partial response; SD: Stable disease; RECIST: Response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; HR: Hazard ratio.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JZ, YW carried out the molecular genetic studies; JD, MZ, ZW, JZ, SW, LY, TA, MW participated in Provision of study materials or patients and collection and assembly of data; LW, JZ, YW, HB and JW analyzed final data and JZ, YW, JW drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ informations

Supported by grants from National Natural Sciences Foundation Distinguished Young Scholars (81025012), National Natural Sciences Foundation General Program (81172235), Beijing Health Systems Academic Leader (2011-2-22).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Methylated and unmethyalted bands of Wnt antagonist genes and wild/mutant EGFR. S1: The example graphs of methylated and unmethyalted bands of Wnt antagonist genes (A) and EGFR wild (B) and mutation types (C, D) by methylation specific PCR and DHPLC respectively. Figure S2 PFS with different epigenotypes of Wnt antagonist genes. Figure2S A-F.Kaplan-Meier curves of comparing the progression free survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP1(A), SFRP2 (B), DKK3 (C), APC (D), CDH1 (E) and combination analysis (F). Figure S3 OS with different epigenotypes of Wnt antagonist genes. Figure3S A-F. Kaplan-Meier curves of comparing the overall survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP1 (A), SFRP2 (B), DKK3 (C), APC (D), CDH1 (E) and combination analysis (F).

Contributor Information

Jian Zhu, Email: zhujian1204@yahoo.com.

Yuyan Wang, Email: gentle_lu@yahoo.com.cn.

Jianchun Duan, Email: duan1961@sina.com.

Hua Bai, Email: baihuahb@sina.com.

Zhijie Wang, Email: jie_969@163.com.

Lai Wei, Email: snowflake201@sina.com.

Jun Zhao, Email: antt508@sina.com.

Minglei Zhuo, Email: Minglei1978@163.com.

Shuhang Wang, Email: snowflake201@gmail.com.

Lu Yang, Email: gentle_lu@yahoo.com.cn.

Tongtong An, Email: antt508@sina.com.

Meina Wu, Email: wumeina@sohu.com.

Jie Wang, Email: wangjie_cc@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr.BM Zhu for her critical review of this manuscript and Dr Ning Wang in the radiological department of Beijing Cancer Hospital for his assessments of the response of treatment. We thank Dr.Guoshuang Feng in (Chaoyang District Center for Disease Control and Prevention) for statistical analysis.

References

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T. et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, Read W, Tierney R, Vlahiotis A. et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: Analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekido Y, Fong KM, Minna JD. Progressin understanding the molecular pathogenesis of human lung cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F21–F59. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossella F, Pereira JR, Pawel JV, Pluzanska A, Gorbounova V, Kaukel E. et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus patinnum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced NSCLC: the TAX326 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingarm S. First-line chemotherapy for advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer: focus on docetaxel. Clin Lung Cancer. 2005;7:S77–S82. doi: 10.3816/clc.2005.s.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmont V, Aerts JG, Tan KY, Schramel F, Vernhout R, Hoogsteden HC, Non-cross resistant sequential single agent chemotherapy in first-line advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: results of a phase II study. J Oncol. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N. et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H. et al. Gefitinib or Chemotherapy for Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with Mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, Negoro S, Okamoto I, Tsurutani J. et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou CC, Wu YL, Chen GY, Feng JF, Liu XQ, Wang CL. et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;8(12):735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell R, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Cardenal F, Erlotinib vs chemotherapy (CT) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients(P) with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activating mutations: interim results of the European Tarceva vs chemotherapy (EURTAC) phase III randomized trial. ASCO. 2011. p. abs7503.

- Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S. et al. EGF mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW. et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non–small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I. et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never -smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar AF, Shigematsu H, Herz J, Minna JD. Mutations and addiction to EGFR: the Achilles ‘heal’ of lung cancers? Trends Mol Med. 2004;10(10):482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudomi T, Kosaka T, Yatabe Y. Biological and clinical implications of EGFR mutations in lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11(3):190–198. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist LV, Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haber DA. Molecular predictors of response to epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):587–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Jänne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M. et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song YC, Hyland C, Park JO. et al. MET Amplification Leads to Gefitinib Resistance in Lung Cancer by Activating ERBB3 Signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig B, Behrens J. The Wnt signaling pathway and its role in tumor development. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:199–221. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M. WNT/PCP signaling pathway and human cancer [review] Oncol Rep. 2005;14:1583–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoschuetzky H, Aberle H, Kemler R. Beta-Catenin mediates the interaction of the cadherin-catenin complex with epidermal growth factor receptor. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1375–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Shigematsu H, Nakajima T, Kubo R, Motohashi S, Sekine Y. et al. Synchronous Alterations of Wnt and Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Pathways through Aberrant Methylation and Mutation in Non –Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6087–6092. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA. et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazieres J, He B, You L, Xu ZD, Lee AY, Mikami I. et al. Wnt inhibitory factor-1 is silenced by promoter hypermethylation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4717–4720. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabender J, Usadel H, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Lord RV. et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli gene promoter hypermethylation in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with survival. Oncogene. 2001;20(27):3528–3532. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Kim MJ, Lee JY, Park JY, Kim DS. Aberrant methylation of E-cadherin and H-cadherin genes in non-small cell lung cancer and its relation to clinicopathologic features. Cancer. 2007;12:2785–2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Mao L, Wang SH, Zhao J, Yang L, An TT. et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Mutations in Plasma DNA Samples Predict Tumor Response in Chinese Patients With Stages IIIB to IV Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2653–2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EA, Gore SD, Hooker C, McDevitt MA, Karp JE, Smith BD. et al. Acute myeloid leukemia is characterized by Wnt pathway inhibitor promoter hypermethylation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(9):1711–1719. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.496505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su HY, Lai HC, Lin YW, Liu VY, Chen CK, Chou YC. et al. Epigenetic silencing of SFRP5 is related to malignant phenotype and chemoresistance of ovarian cancer through Wnt signaling pathway. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(3):555–567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Bu X, Zhang N, Wang W. Downregulation of SFRP5 expression and its inverse correlation with those of MMP-7 and MT1-MMP in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogabe Y, Suzuki H, Toyota M, Ogi K, Imai T, Nojima M. et al. Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;32(6):1253–1261. doi: 10.3892/ijo_32_6_1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu XM, Zhao CH, Zhang N, Gao F, Lin S, Dai XW. Hypermethylation and aberrant expression of secreted frizzled-related protein genes in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(21):3421–3424. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeck J, Geisler C, Noetzel E, Alkaya S, Hartmann A, Knuchel R. et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the secreted frizzled-related protein-5 (SFRP5) gene in human breast cancer is associated with unfavorable prognosis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(5):991–998. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke KS, Staib P, Puetter A, Gehrke I, Gandhirajan RK, Schlösser A. et al. Small molecule inhibitors of WNT signaling effectively induce apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Eur J Haematol. 2009;82(3):165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. DNA methylation and cancer therapy: new developments and expectations. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(1):55–60. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000147383.04709.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Methylated and unmethyalted bands of Wnt antagonist genes and wild/mutant EGFR. S1: The example graphs of methylated and unmethyalted bands of Wnt antagonist genes (A) and EGFR wild (B) and mutation types (C, D) by methylation specific PCR and DHPLC respectively. Figure S2 PFS with different epigenotypes of Wnt antagonist genes. Figure2S A-F.Kaplan-Meier curves of comparing the progression free survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP1(A), SFRP2 (B), DKK3 (C), APC (D), CDH1 (E) and combination analysis (F). Figure S3 OS with different epigenotypes of Wnt antagonist genes. Figure3S A-F. Kaplan-Meier curves of comparing the overall survival of patients with different epigenotypes of SFRP1 (A), SFRP2 (B), DKK3 (C), APC (D), CDH1 (E) and combination analysis (F).