Abstract

Introduction:

The causal relationship between tobacco smoking and a variety of cancers is attributable to the carcinogens that smokers inhale, including tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs). We aimed to assess the exposure to TSNAs in waterpipe smokers (WPS), cigarette smokers (CS), and nonsmoking females exposed to tobacco smoke.

Methods:

We measured 2 metabolites, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) and its glucuronides (NNAl-Gluc) in the urine of males who were either current CS or WPS, and their wives exposed to either cigarette or waterpipe smoke in a sample of 46 subjects from rural Egypt.

Results:

Of the 24 current male smokers, 54.2% were exclusive CS and 45.8% were exclusive WPS. Among wives, 59.1% reported exposure to cigarette smoke and 40.9% to waterpipe smoke. The geometric mean of urinary NNAL was 0.19 ± 0.60 pmol/ml urine (range 0.005–2.58) in the total sample. Significantly higher levels of NNAL were observed among male smokers of either cigarettes or waterpipe (0.89 ± 0.53 pmol/ml, range 0.78–2.58 in CS and 0.21–1.71 in WPS) compared with nonsmoking wives (0.04 ± 0.18 pmol/ml, range 0.01–0.60 in CS wives, 0.05–0.23 in WPS wives, p = .000). Among males, CS had significantly higher levels of NNAL compared with WPS (1.22 vs. 0.62; p = .007). However, no significant difference was detected in NNAL levels between wives exposed to cigarette smoke or waterpipe smoke.

Conclusions:

Cigarette smokers levels of NNAL were higher than WPS levels in males. Exposure to tobacco smoke was evident in wives of both CS and WPS. Among WPS, NNAL tended to increase with increasing numbers of hagars smoked/day.

Introduction

The tobacco epidemic kills nearly 6 million people a year from lung cancer, heart disease, and other illnesses. By 2030, the death toll will exceed eight million a year, and 80% of those deaths will occur in the developing world (World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). In Egypt, about one third of deaths resulting from cancer are caused by tobacco, with tobacco-attributable cardiovascular and respiratory diseases accounting for about 30% each. In Egypt, tobacco-related cancers as a percentage of all cancers are on the rise. Among men, the proportion rose from 8.9% of total deaths occurring after the age of 34 years to 14.8% between 1974 and 1987. Among women, the proportion is still relatively low. In 2004, tobacco-attributable deaths in Egypt were estimated to be nearly 170,000. Over 90% of these deaths were among men (Hanafy et al., 2010).

In addition to the disease burden attributed to cigarette smoking, Egypt, and other countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region have experienced an upsurge in waterpipe smoking, particularly among youth. The waterpipe is a method of smoking in which the tobacco smoke passes into water before being inhaled by the smoker. The waterpipe device is composed of a holder to burn tobacco with charcoal on top, called a korsi. The tobacco load on the korsi is called hagar. The prevalence of current waterpipe use among students was reported to be 19% in Egypt, 14.6% in Saudi Arabia, 20%–44% in Lebanon, and 23.5% in Syria (Almerie et al., 2008; Al-Mohamed & Amin, 2010; Saade, Warren, Jones, & Mokdad, 2009; Gadalla et al., 2003). In addition to its popularity among young men and women, the widespread belief that waterpipe smoking is less harmful than cigarette smoking (Labib et al., 2007) has encouraged many cigarette smokers to switch to waterpipes while they attempt to quit cigarette smoking (Chaaya, Jabbour, El-Roueiheb, & Chemaitelly, 2004; Fadhil, 2007; Hammal, Mock, Ward, Eissenberg, & Maziak, 2008). Certain groups of people may be particularly vulnerable to switching tobacco products, including pregnant women who may replace cigarettes with waterpipe smoking during pregnancy based on this false belief. For example, in Lebanon, Chaaya et al. (2004) reported cigarette smoking prevalence of 17% and waterpipe smoking prevalence either alone or in combination with cigarette smoking of nearly 6% among pregnant women.

Despite the scarcity of data on the carcinogenicity of waterpipe smoking, preliminary studies have linked waterpipe use to increased risk of lung (Akl et al., 2010; Gupta, Boffetta, Gaborieau, & Jindal, 2001; Lubin et al., 1990), oral (El-Hakim & Uthman, 1999), bladder (Bedwani et al., 1997; Roohullah, Nusrat, Hamdani, Burdy, & Khurshid, 2001), esophageal, and gastric cancer (Gunaid et al., 1995; Nasrollahzadeh et al., 2008). In addition, waterpipe smoking has been associated with increased frequency of chromosomal damage (El-Setouhy et al., 2008; Khabour, Alsatari, Azab, Alzoubi, & Sadiq, 2010; Yadav & Thakur, 2000).

The causal relationship between tobacco smoking and cancer is attributable to the numerous carcinogens that smokers inhale, including tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs). TSNAs are a class of carcinogens that are formed during the curing, processing, fermentation, and combustion of tobacco (Adams, Lee, Vinchkoski, Castonguay, & Hoffmann, 1983; Hoffmann, Brunnemann, Prokopczyk, & Djordjevic, 1994). They have been identified in cigarette tobacco (Ashley et al., 2003; Brunnemann, Cox, & Hoffmann, 1992; Song & Ashley, 1999), environmental tobacco smoke (ETS; Brunnemann et al., 1992), smokeless tobacco (Hoffmann, Adams, Lisk, Fisenne, & Brunnemann, 1987), and other tobacco products such as cigars, toombak, and bidi cigarettes (Idris, Prokopczyk, & Hoffmann, 1994; McNeill, Bedi, Islam, Alkhatib, & West, 2006; Murphy, Carmella, Idris, & Hoffmann, 1994; Nair, Pakhale, & Bhide, 1989). Furthermore, TSNA yields in tobacco smoke vary significantly in tested cigarettes from different parts of the world as the formation of TSNAs is influenced by the tobacco blend and the curing processes (Ashley et al., 2003; Ding et al., 2006).

The most carcinogenic of the commonly occurring tobacco-specific nitrosamines is 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK; Hecht, 1998). NNK and its metabolite NNAL are metabolically activated to reactive intermediates that are carcinogenic. NNAL is detoxified by glucuronidation, and urinary metabolites of NNAL and its glucuronides (NNAL-Glucuronide) are useful biomarkers of NNK uptake in humans (Kavvadias et al., 2009; Xia, Bernert, Jain, Ashley, & Pirkle, 2011). Advantages of the NNAL and NNAL-Glucuronide (NNAL-Gluc) biomarkers include tobacco specificity, direct relevance to carcinogen uptake, and consistent detection in exposed individuals (Carmella, Han, Fristad, Yang, & Hecht, 2003; Hecht, 1998, 2002). NNAL (free NNAL plus NNAL-Gluc), has been measured in studies of NNK uptake in cigarette smokers (Anderson et al., 2001; Carmella, Akerkar, & Hecht, 1993; Carmella, Akerkar, Richie, & Hecht, 1995; Carmella, Le Ka, Upadhyaya, & Hecht, 2002; Richie et al., 1997; Murphy et al., 2004; Muscat, Djordjevic, Colosimo, Stellman, & Richie, 2005), smokeless tobacco users (Hecht, 2002; Murphy et al., 1994; Stepanov, Jensen, Hatsukami, & Hecht, 2008), and nonsmokers exposed to ETS (Anderson et al., 2001; Hecht et al., 1993). Little or no reported research has assessed NNK carcinogenic uptake in waterpipe smokers. In this study, we quantified two of its metabolites, NNAL and NNAL-Gluc, in the urine of Egyptian males who were either current cigarette or waterpipe smokers, as compared with nonsmoking females exposed to ETS from cigarettes or waterpipe, respectively.

Methods

Study Participants

We previously conducted a baseline smoking prevalence survey in nine villages in the Qalyubia governorate in Delta Egypt (Auf et al., 2012; Boulos et al., 2009; Radwan et al., 2007). In each village, 300 households were selected using a systematic random sample, and adults (aged ≥ 18 years) were interviewed for their demographics, smoking and quitting behaviors, exposure to ETS, and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward a variety of smoking-related variables. Eligible subjects for the current study of TSNA were recruited from one of those villages (sidbis), utilizing the same systematic random sampling methods. Eligible subjects were adult males and their wives, aged 18 years and above; the females were nonsmokers, and the males were current smokers of cigarettes or waterpipe at the time of enrollment. There were no refusals. Current cigarette smokers were defined as those who had at least 5 years of smoking history and averaged 10 cigarettes/day or more in the past year. Current waterpipe smokers were defined as those who smoked at least once per day in the previous 4 weeks. This definition was based on findings from previous research, which revealed that compared with cigarette smoking, waterpipe smoking is characterized by less frequent exposure (one to four sessions per day) but with a much more intense exposure per session, which varies between 15 and 90 min. A regular user of waterpipe, on average smokes 2–3 sessions per day. Furthermore, the data from a national survey revealed that the exposure level of waterpipe tobacco smoking in terms of average number of hagars per day is only 2.8 + 2.7 (range 1–20/day; World Health Organization: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2006).

Measures

After obtaining signed informed consent (approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Ministry of Health and Population in Egypt and of Georgetown University), trained interviewers administered a questionnaire that elicited information about demographics, cigarette, and waterpipe smoking history (e.g., age at smoking onset, number of cigarettes or hagars smoked per day, duration of smoking) and frequency of daily waterpipe smoking (number of days of smoking per week and number of times of smoking per day). Nicotine dependence was assessed in cigarette smokers using the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991). Nonsmoking females were asked about the number of smokers in their houses and the extent of exposure to ETS at home (number of days/week and number of hours/day). We also assessed the frequency of exposure to ETS in other settings such as in public/private transportation (number of days per week) and in large gatherings such as weddings. These rural nonsmoking females were housewives, so we assumed that the aforementioned places are the ones with the highest level of exposure to tobacco smoke.

Subjects were asked to provide 50 ml of urine in sterile plastic cups, which were placed immediately in ice boxes until they were transferred to the lab at the National Hepatology and Tropical Medicine Research Institute in Cairo, where they were stored at −800C. Before samples were shipped to the lab in the United States, they were thawed and aliquoted in 4.5 ml aliquots. The urinary total NNAL, expressed as pmol/ml urine (sum of the NNAL and NNAL-gluc levels), was quantified from 4 ml of urine per subject as previously described by Church et al. (2010), using a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) interfaced with a Thermal Energy Analyzer (Orlon Research, Beverly, MA). The intraday and interday precision of the method was 6.4% and 7.5%, respectively, with an accuracy of >95%. The limit of quantitation was 0.15 pmol/ml urine.

Data Management and Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Access database. Duplicate data entry was performed to ensure quality control. Descriptive data analysis was conducted to examine the ranges and distribution of continuous variables. Data were examined for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test: NNAL values were skewed and were described as geometric means. Student’s t test (continuous variables) and chi-square test (categorical variables) were used to compare demographics and smoking behavior variables between cigarette and waterpipe smokers, and characteristics of exposure to ETS between nonsmoking females exposed either to cigarette or waterpipe smoke. When the expected numbers were small (<5 subjects per cell), Fisher’s exact method was used. Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to evaluate the differences in the levels of NNAL in binary and categorical variables respectively. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the association between levels of NNAL in nonsmoking females exposed to tobacco smoke and NNAL levels in their husbands and with the number of cigarettes/hagars they smoked in the past 24 hr. SPSS statistical software (release 15) was used for data analysis. All statistical tests were two sided, with 0.05 as the level of significance.

Results

A total of 51 subjects were recruited, of whom 46 were successfully assayed: 24 (52.2%) were males and 22 (47.8%) were nonsmoker wives. The demographic characteristics and smoking profiles of participants are shown in Table 1. Of the 24 current male smokers, 13 (54.2%) were exclusive cigarette smokers, and 11 (45.8) were exclusive waterpipe smokers. Among nonsmoking females, 13 (59.1%) reported being exposed to cigarette smoke, and 9 (40.9%) reported exposure to waterpipe smoke. All interviewed subjects were married; the majority had received no formal education (62.5% in males and 72.7% in nonsmoking females). The mean age was 45.3 ± 10.4 (range 24–60 years) in cigarette smokers and 45.4 ± 15.9 (range 20–65 years) in waterpipe smokers (p > .05). The mean age was 36.1 ± 11.7 (range 21–60 years) in nonsmoking females who reported exposure to cigarette smoke and 43.1 ± 11.5 (range 24–57 years) in nonsmoking females exposed to waterpipe smoke (p > .05).

Table 1.

Study Subject Characteristics by Smoking Status (n = 46)

| Cigarette (N = 13) | Waterpipe (N = 11) | p Valuea | |

| Current male smokers | |||

| Age (M ± SD) | 45.3 (10.4) | 45.4 (15.9) | .99 |

| Education (formal), N | 6 | 3 | .42 |

| Age at smoking initiation (M ± SD) | 18.4 (6.0) | 18 (5.4) | .75 |

| Cigarettes/hagars per day (M ± SD) | 21.5 (6.6) | 11.9 (10.9) | .01 |

| Duration of smoking (years; M ± SD) | 16 (10.8) | 16.3 (12.4) | .95 |

| FTND (M ± SD) | 4.5 (1.1) | – | – |

| Frequency of daily waterpipe smoking (5 times and more), N | – | 6 | – |

| Nonsmoking females exposed to ETS | |||

| Cigarette ETS (N = 13) | Waterpipe ETS (N = 9) | p Value | |

| Age (M ± SD) | 36.1 (11.7) | 43.1 (11.6) | .19 |

| Education (formal), N | 4 | 2 | .52 |

| Number of household smokers (more than one smoker) N | 2 | 5 | .06 |

| Number of hours of exposure to ETS at home (M ± SD) | 3.5 (3.01) | 2.2 (1.6) | .27 |

| Attendance of a celebration last week, N | 4 | 1 | .29 |

Note. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; ETS = environmental tobacco smoke.

p Values are from the t test (continuous variables) or Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables).

Both cigarette and waterpipe smokers had similar ages of smoking initiation and number of years of smoking (p > .05). On average, cigarette smokers consumed 21.5 ± 7 cigarettes/day, and waterpipe smokers consumed 11.9 ± 11 hagars (tobacco wads) per day. The mean FTND was 4.5 ± 1 in cigarette smokers, similar to previous studies (Park et al. 2004; Spitz et al., 1998). All waterpipe smokers were daily users.

All nonsmoking females reported that their husbands smoked in their presence and that they were exposed daily to ETS. Those exposed to cigarette smoke had a higher mean number of hours of exposure per day, compared with those exposed to waterpipe smoke (3.5 vs. 2.2 hr per day, p > .05). However, a higher proportion of nonsmoking females exposed to waterpipe smoke reported presence of more than one smoker in their household (55.6% vs. 15.4%, p > .05; Table 1).

In addition, NNAL levels in nonsmoking females correlated with NNAL levels in their husbands (r = 0.94; p = .0001 for cigarette smoking and r = 0.67, p = .03 for waterpipe smoking), but these levels were not correlated with the number of cigarettes/hagars their husbands smoked in the past 24 hr(r = 0.07, p = .80 for cigarette smoking and r = −0.32, p = .40 for waterpipe smoking). Almost all interviewed nonsmoking females (21 of 22) reported no exposure to ETS in methods of transportation in the past 7 days (all were housewives).

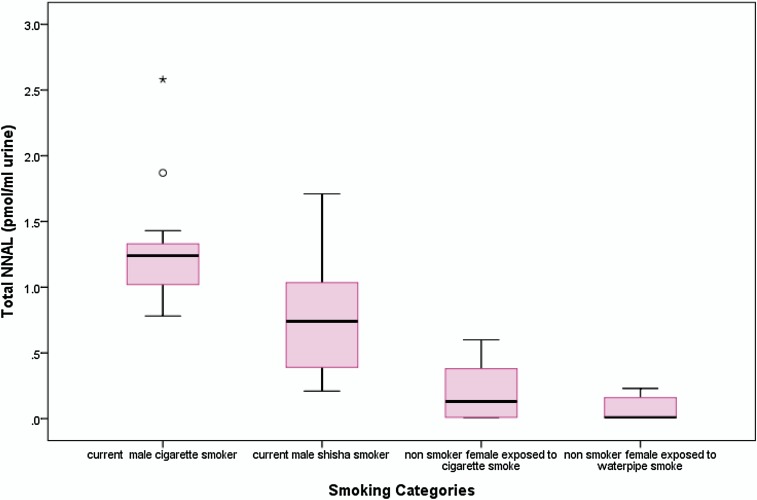

The geometric mean of urinary NNAL was 0.19 ± 0.60 pmol/ml urine (range 0.005–2.58). A significantly higher level of urinary NNAL was observed among males who currently smoked either cigarettes or waterpipe (0.89 ± 0.53 pmol/ml, range 0.21–2.58) compared with nonsmoking females (0.04 ± 0.18 pmol/ml, range 0.005–0.60, p < .001). Among males, cigarette smokers had significantly higher levels of urinary NNAL compared with waterpipe smokers (1.22 vs. 0.62; p = .007; Table 2, Figure 1). Adjusting for the duration, since smokers had their last cigarette or waterpipe (dichotomized as < 1 hr and ≥1 hr), revealed persistent higher levels of urinary NNAL in cigarette smokers compared with waterpipe smokers. The difference was statistically significant only when comparing cigarette and waterpipe smokers who had smoked within less than 1 hr (1.17 vs. 0.56, p = .02; 1.42 vs. 0.67, p = .07).

Table 2.

Geometric Mean Levels of NNAL by Different Smoking Variables in Cigarette and Waterpipe Smokers (n = 24)

| Geometric mean NNAL (SD) | p Valuea | |

| Current cigarette smokers (N = 13) | 1.22 (0.47) | .007 |

| Current waterpipe smokers (N = 11) | 0.62 (0.46) | |

| Cigarette smokers | ||

| Cigarettes/day | ||

| ≤15 cigarettes (n = 2) | 0.96 (0.07) | |

| 16–20 cigarettes (n = 9) | 1.35 (0.51) | |

| >20 cigarettes (n = 2) | 1.00 (0.36) | .21 |

| Morning smoking | ||

| No (n = 4) | 1.06 (0.20) | |

| Yes (n = 9) | 1.67 (0.62) | .03 |

| Duration of smoking | ||

| <15 years (n = 6) | 1.00 (0.23) | |

| ≥15 years and more (n = 7) | 1.45 (0.53) | .07 |

| Waterpipe smokers | ||

| Hagars per day | ||

| <5 hagars (n = 3) | 0.39 (0.54) | |

| 5–10 hagars (n = 3) | 0.51 (0.34) | |

| 11 or more hagars (n = 5) | 0.91 (0.45) | .33 |

| Frequency of daily waterpipe smoking | ||

| <5 times (n = 5) | 0.39 (0.39) | |

| ≥5 times (n = 6) | 0.91 (0.40) | .08 |

| Duration of smoking | ||

| <15 years (n = 5) | 0.72 (0.58) | |

| ≥15 years (n = 6) | 0.54 (0.33) | .42 |

Note. a p Value of Mann–Whitney test for binary and Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical variables. NNAL = 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol.

Figure 1.

Box plot of total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol in the urine of male smokers (cigarettes and waterpipe) and nonsmoking females exposed to ETS.

In cigarette smokers, levels of urinary NNAL were highest among subjects who consumed between 16 and 20 cigarettes daily (Table 2). A significant association was observed between urinary NNAL and morning smoking; assessed using the FTND question “Do you smoke more in the earlier hours of your day soon after waking than in the remainder of the day?” (p = .03) and to some extent with lifetime duration of smoking (p = .07). Among waterpipe smokers, NNAL increased with increasing numbers of hagars smoked per day (Table 2). No significant difference was detected in urinary NNAL between nonsmoking females exposed to cigarette smoke and those exposed to waterpipe smoke, nor were there any associations between the NNAL levels of nonsmoking females and the number of smokers in the house or number of hours of their self-reported ETS exposure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Geometric Mean Levels of NNAL by Different Reported Exposures in Nonsmoking Females (n = 22)

| Geometric mean NNAL (SD) | p Valuea | |

| Nonsmoking female exposed to cigarette smoke (N = 13) | 0.05 (0.21) | .39 |

| Nonsmoking female exposed to waterpipe smoke (N = 9) | 0.02 (0.09) | |

| Number of smokers within the household | .89 | |

| One smoker (n = 15) | 0.03 (0.19) | |

| More than one smoker (n = 7) | 0.04 (0.16) | |

| Smoke exposure at home | .80 | |

| Less than 1 hr (n = 2) | 0.04 (0.13) | |

| 1–5 hr (n = 17) | 0.06 (0.19) | |

| 6 hr and above (n = 3) | 0.03 (0.17) | |

| Smoke exposure at a large gathering (e.g., wedding) | .07 | |

| No (n = 17) | 0.02 (0.14) | |

| Yes (n = 5) | 0.14 (0.23) |

Note. a p Value of Mann–Whitney test for binary and Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical variables. NNAL = 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol.

Discussion

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the NNK uptake in waterpipe smokers compared with cigarette smokers. Understanding the potential differences in such carcinogenic exposures is critical for the assessment of harm associated with waterpipe smoking and for generating the evidence needed for effective tobacco control addressing this method of smoking.

Smokers and nonsmokers exposed to ETS in our study excreted NNAL and NNAL-Gluc in their urine, consistent with previous research findings (Carmella et al., 1993; Hecht et al., 1993; Joseph et al., 2005; Murphy et al., 2004). Levels of NNAL in current male smokers were significantly higher in our study than in nonsmoking females. These data indicate that carcinogen uptake in nonsmokers exposed to ETS is substantially less than in smokers, which is consistent with previous studies (Hecht, 2006), and the epidemiological data showing lower risk of lung cancer in nonsmokers (Environmental Protection Agency, 1992; US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986, 2006).

Our results showed elevated levels of urinary NNAL in cigarette smokers compared with waterpipe smokers. Levels in cigarette smokers were twice that in waterpipe smokers, but waterpipe smokers had a median NNAL that was still much higher than that of nonsmokers, as shown in Figure 1. Consistent with this finding, Schubert et al. (2011) reported lower levels of TSNAs measured in waterpipe smoke compared with cigarette smoke; however, the levels of benzo[a]pyrene were 3 times higher in waterpipe smoke samples. Other researchers reported similar findings on levels of various polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in waterpipe smoke. For example, Shihadeh and Saleh (2005) reported that relative to the smoke from a single cigarette, waterpipe smoke delivered greater quantities of tar and PAH compounds. More recently, Sepetdjian, Shihadeh, and Saliba (2008) concluded that a single waterpipe smoking session delivers approximately 50 times the quantities of the carcinogenic PAH as a single cigarette smoked. Furthermore, an inverse relationship between the yield of TSNAs and PAH has been consistently observed. For example, Ding et al. (2006) reported that PAH were inversely correlated with total carcinogenic TSNAs and nitrate content, confirming earlier studies which demonstrated that tobacco blend (types of tobacco) and nitrate levels (formed during tobacco combustion) influence the mainstream yields of PAH and TSNA (Adams, Lee, & Hoffmann, 1984; Hoffmann & Wynder, 1967).

Many parameters are known to influence the delivery of TSNA, including the type of tobacco, tobacco blending, and tobacco curing practices (Ashley et al., 2010). In addition to these parameters, there are factors specific to waterpipe smoking that might influence the delivery of TSNA, including the volume of the bowl, the amount and temperature of water, added substances (e.g., flavorings), the solubility of TSNA, and the length of the aspiration hose. Some previous research supports the notion of additional factors; Rakower and Fatal (1962) for example, reported that the tar content of the waterpipe smoke diminished to 50% in the presence of water inside the waterpipe. Similarly, Salem, Mesrega, Shallouf, and Nosir (1990) reported that some of the lead content of waterpipe tobacco is trapped in water, as demonstrated by significantly higher levels of lead in waterpipe water than in tap water and increased levels with increased number of hagars consumed. Notably, it is difficult to quantify exposure in waterpipe smokers as the content of tobacco in hagars varies and is not standardized as in cigarettes. Additionally, waterpipe smokers tend to share the waterpipe in social settings and in cafes. These factors might contribute to the lower levels of urinary TSNA detected in waterpipe smokers.

Among cigarette smokers in our study, the total NNAL was not correlated directly with the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Similarly, Joseph et al. (2005) reported that levels of NNAL increased with increasing number of cigarettes smoked per day, but not in a linear fashion, particularly at higher amounts of cigarette consumption. Furthermore, they pointed out some factors that may contribute to the lack of a correlation between carcinogenic biomarkers and tobacco consumption in association studies, including degree of smoking inhalation, biomarker metabolism, the time of urine collection relative to smoking, and lack of precision in reporting the number of cigarettes per day that could be due to faulty recall or rounding errors. Interestingly, NNAL levels increased steadily with increasing numbers of hagars consumed in our study, but further research is necessary to adequately characterize the dose–response relationship, including aspects of dependency as assessed by the recently constructed and validated “Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale” (Salameh, Waked, & Aoun, 2008).

In conclusion, NNK uptake was evident in this study of smokers and nonsmokers in Egypt. Nonsmoking females reported detectable levels of NNAL which significantly correlated with NNAL levels in their smokers’ husbands. Our results suggest that cigarette smokers receive greater exposure to NNK compared with waterpipe smokers, as measured by urinary NNAL, but waterpipe smokers in turn have much higher levels of exposure than do nonsmokers. The small sample size and imprecise characterization of daily tobacco (hagars) consumption are limitations to the study. Thus, definite conclusions about carcinogenic exposure in waterpipe smokers warrant future research, in order to more precisely determine the exposure levels and provide evidence of biological harm.

Funding

The project was supported by National Institutes of Health grant number R01-TW05944 (Principal Investigator: CL).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

This pilot study emerged from initial discussions between the authors and Dr. Nargis Labib of Cairo University and the late Dr. Mostafa Kamel Mohamed of Ain Shams University. We are grateful for their input to the study design. The Center For Applied Research in Qalyubia governorate, Egypt, recruited the subjects and collected specimens; the authors thank Dr. Fatma Abdel Aziz for directing the field work. Dr. Nabiel N. Mikhail directed the data entry and data management for this study.

References

- Adams JD, Lee SJ, Hoffmann D. Carcinogenic agents in cigarette smoke and the influence of nitrate on their formation. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:221–223. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.2.221. doi:10.1093/carcin/5.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JD, Lee SJ, Vinchkoski N, Castonguay A, Hoffmann D. On the formation of the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone during smoking. Cancer Letters. 1983;17:339–346. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(83)90173-8. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(83)90173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: A systematic review. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39:834–857. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq002. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almerie MQ, Matar HE, Salam M, Morad A, Abdulaal M, Koudsi A, et al. Cigarettes and waterpipe smoking among medical students in Syria: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2008;12:1085–1091. Retrieved from http://www.theunion.org/index.php/en/journals/the-journal. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohamed HI, Amin TT. Pattern and prevalence of smoking among students at King Faisal University, Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2010;16:56–64. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/publications/emhj/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KE, Carmella SG, Ye M, Bliss RL, Le C, Murphy L, et al. Metabolites of a tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in nonsmoking women exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93:378–381. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.378. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.5.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley DL, Beeson MD, Johnson DR, McCraw JM, Richter P, Pirkle JL, et al. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines in tobacco from U.S. brand and non-U.S. brand cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:323–331. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000095311. doi:10.1080/14622200307202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley DL, O’Connor RJ, Bernert JT, Watson CH, Polzin GM, Jain RB, et al. Effect of differing levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in cigarette smoke on the levels of biomarkers in smokers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2010;19:1389–1398. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0084. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auf RA, Radwan GN, Loffredo CA, El Setouhy M, Israel E, Mohamed MK. Assessment of tobacco dependence in waterpipe smokers in Egypt. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases. 2012;16:132–137. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0457. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedwani R, el-Khwsky F, Renganathan E, Braga C, Abu Seif HH, Abul Azm T, et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer in Alexandria, Egypt: Tobacco smoking. International Journal of Cancer. 1997;73:64–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<64::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<64::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulos DN, Loffredo CA, El Setouhy M, Abdel-Aziz F, Israel E, Mohamed MK. Nondaily, light daily, and moderate-to-heavy cigarette smokers in a rural area of Egypt: A population-based survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:134–138. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp016. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunnemann KD, Cox JE, Hoffmann D. Analysis of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines in indoor air. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2415–2418. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2415. doi:10.1093/carcin/13.12.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmella SG, Akerkar SA, Hecht SS. Metabolites of the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in smokers’ urine. Cancer Research. 1993;53:721–724. Retrieved from http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmella SG, Akerkar SA, Richie JP, Jr, Hecht SS. Intraindividual and interindividual differences in metabolites of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) in smokers’ urine. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 1995;4:635–642. Retrieved from http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmella SG, Han S, Fristad A, Yang Y, Hecht SS. Analysis of total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in human urine. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2003;12:1257–1261. Retrieved from http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmella SG, Le Ka KA, Upadhyaya P, Hecht SS. Analysis of N- and O-glucuronides of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in human urine. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2002;15:545–550. doi: 10.1021/tx015584c. Retrieved from http://pubs.acs.org/journal/crtoec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaaya M, Jabbour S, El-Roueiheb Z, Chemaitelly H. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of argileh (water pipe or hubble-bubble) and cigarette smoking among pregnant women in Lebanon. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1821–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church TR, Anderson KE, Le C, Zhang Y, Kampa DM, Benoit AR, et al. Temporal stability of urinary and plasma biomarkers of tobacco smoke exposure among cigarette smokers. Biomarkers. 2010;15:345–352. doi: 10.3109/13547501003753881. doi:10.3109/13547501003753881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YS, Yan XJ, Jain RB, Lopp E, Tavakoli A, Polzin GM, et al. Determination of 14 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream smoke from U.S. brand and non-U.S. brand cigarettes. Environmental Science & Technology. 2006;40:1133–1138. doi: 10.1021/es0517320. doi:10.1021/es0517320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hakim IE, Uthman MA. Squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma of the lower lip associated with “Goza” and “Shisha” smoking. International Journal of Dermatology. 1999;38:108–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00448.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Setouhy M, Loffredo CA, Radwan G, Abdel Rahman R, Mahfouz E, Israel E, et al. Genotoxic effects of waterpipe smoking on the buccal mucosa cells. Mutation Research. 2008;655:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.06.014. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Respiratory health effects of passive smoking: Lung cancer and other disorders. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1992. Retrieved from http://www.epa.gov/ord/ [Google Scholar]

- Fadhil I. Tobacco control in Bahrain: An overview. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2007;13:719–726. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/publications/emhj/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadalla S, Aboul-Fotouh A, El-Setouhy M, Mikhail N, Abdel-Aziz F, Mohamed MK, et al. Prevalence of smoking among rural secondary school students in Qualyobia governorate. Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 2003;33:1031–1050. Retrieved from http://www.parasitology.eg.net/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaid AA, Sumairi AA, Shidrawi RG, al-Hanaki A, al-Haimi M, al-Absi S, et al. Oesophageal and gastric carcinoma in the Republic of Yemen. British Journal of Cancer. 1995;71:409–410. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.83. doi:10.1038/bjc.1995.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta D, Boffetta P, Gaborieau V, Jindal SK. Risk factors of lung cancer in Chandigarh, India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2001;113:142–150. Retrieved from www.icmr.nic.in/ijmr/ijmr.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammal F, Mock J, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. A pleasure among friends: How narghile (waterpipe) smoking differs from cigarette smoking in Syria. Tobacco Control. 2008;17:e3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020529. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.020529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafy K, Saleh ASE, Elmallah MEBE, Omar HMA, Bakr D, Chaloupka FJ. The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in Egypt. Paris, France: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/tfi/PDF/Egypt_Report_Online_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. Biochemistry, biology, and carcinogenicity of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 1998;11:559–603. doi: 10.1021/tx980005y. Retrieved from http://pubs.acs.org/journal/crtoec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer: Chemical mechanisms and approaches to prevention. Lancet Oncology. 2002;3:461–469. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00815-x. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(02)00815-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. A biomarker of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and Ernst Wynder’s opinion about ETS and lung cancer. Preventive Medicine. 2006;43:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.020. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS, Carmella SG, Murphy SE, Akerkar S, Brunnemann KD, Hoffmann D. A tobacco-specific lung carcinogen in the urine of men exposed to cigarette smoke. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1543–1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311183292105. doi:10.1056/NEJM199311183292105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D, Adams JD, Lisk D, Fisenne I, Brunnemann KD. Toxic and carcinogenic agents in dry and moist snuff. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1987;79:1281–1286. Retrieved from jnci.oxfordjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D, Brunnemann KD, Prokopczyk B, Djordjevic MV. Tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines and Areca-derived N-nitrosamines: Chemistry, biochemistry, carcinogenicity, and relevance to humans. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 1994;41:1–52. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531825. doi:10.1080/15287399409531825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. The reduction of the tumorigenicity of cigarette smoke condensate by addition of sodium nitrate to tobacco. Cancer Research. 1967;27:172–174. Retrieved from http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idris AM, Prokopczyk B, Hoffmann D. Toombak: A major risk factor for cancer of the oral cavity in Sudan. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:832–839. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1141. doi:10.1006/pmed.1994.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Hecht SS, Murphy SE, Carmella SG, Le CT, Zhang Y, et al. Relationships between cigarette consumption and biomarkers of tobacco toxin exposure. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2005;14:2963–2968. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0768. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavvadias D, Scherer G, Urban M, Cheung F, Errington G, Shepperd J, et al. Simultaneous determination of four tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines (TSNA) in human urine. Journal of Chromatography B. 2009;877:1185–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabour OF, Alsatari ES, Azab M, Alzoubi KH, Sadiq MF. Assessment of genotoxicity of waterpipe and cigarette smoking in lymphocytes using the sister-chromatid exchange assay: A comparative study. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 2010;52:224–228. doi: 10.1002/em.20601. doi:10.1002/em.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labib N, Radwan G, Mikhail N, Mohamed MK, El Setouhy M, Loffredo C, et al. Comparison of cigarette and water pipe smoking among female university students in Egypt. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:591–596. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239696. doi:10.1080/14622200701239696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin JH, Qiao YL, Taylor PR, Yao SX, Schatzkin A, Mao BL, et al. Quantitative evaluation of the radon and lung cancer association in a case control study of Chinese tin miners. Cancer Research. 1990;50:174–180. Retrieved from http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, Bedi R, Islam S, Alkhatib MN, West R. Levels of toxins in oral tobacco products in the UK. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:64–67. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013011. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.013011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SE, Carmella SG, Idris AM, Hoffmann D. Uptake and metabolism of carcinogenic levels of tobacco-specific nitrosamines by Sudanese snuff dippers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 1994;3:423–428. Retrieved from http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SE, Link CA, Jensen J, Le C, Puumala SS, Hecht SS, et al. A comparison of urinary biomarkers of tobacco and carcinogen exposure in smokers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2004;13:1617–1623. Retrieved from http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Djordjevic MV, Colosimo S, Stellman SD, Richie JP., Jr Racial differences in exposure and glucuronidation of the tobacco-specific carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) Cancer. 2005;103:1420–1426. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20953. doi:10.1002/cncr.20953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair J, Pakhale SS, Bhide SV. Carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines in Indian tobacco products. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1989;27:751–753. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(89)90080-x. doi:10.1016/0278-6915(89)90080-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Aghcheli K, Sotoudeh M, Islami F, Abnet CC, et al. Opium, tobacco, and alcohol use in relation to oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a high-risk area of Iran. British Journal of Cancer. 2008;98:1857–1863. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604369. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SM, Son KY, Lee YJ, Lee HC, Kang JH, Chang YJ, et al. A preliminary investigation of early smoking initiation and nicotine dependence in Korean adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan GN, Setouhy ME, Mohamed MK, Hamid MA, Israel E, Azem SA, et al. DRD2/ANKK1 TaqI polymorphism and smoking behavior of Egyptian male cigarette smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:1325–1329. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704889. doi:10.1080/14622200701704889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakower J, Fatal B. Study of narghile smoking in relation to cancer of the lung. British Journal of Cancer. 1962;16:1–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1962.1. doi:10.1038/bjc.1962.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie JP, Jr, Carmella SG, Muscat JE, Scott DG, Akerkar SA, Hecht SS. Differences in the urinary metabolites of the tobacco-specific lung carcinogen 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone in black and white smokers. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 1997;6:783–790. Retrieved from http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roohullah NJ, Nusrat J, Hamdani SR, Burdy GM, Khurshid A. Cancer urinary bladder—5 year experience at Cenar, Quetta. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad. 2001;13:14–16. Retrieved from www.ayubmed.edu.pk/JAMC/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saade G, Warren CW, Jones NR, Mokdad A. Tobacco use and cessation counseling among health professional students: Lebanon Global Health Professions Student Survey. Lebanese Medical Journal. 2009;57:243–247. Retrieved from lebanesemedicaljournal.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salameh P, Waked M, Aoun Z. Waterpipe smoking: Construction and validation of the Lebanon Waterpipe Dependence Scale (LWDS-11) Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:149–158. doi: 10.1080/14622200701767753. doi:789471525 10.1080/14622200701767753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem ES, Mesrega SM, Shallouf MA, Nosir MI. Determination of lead levels in cigarette and Goza smoking components with a special reference to its blood values in human smokers. The Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis. 1990;37 Retrieved from http://www.e-tabeeb.com/?c_cat=&pg=&pg_cat=&go=journals. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert J, Hahn J, Dettbarn G, Seidel A, Luch A, Schulz TG. Mainstream smoke of the waterpipe: Does this environmental matrix reveal as significant source of toxic compounds? Toxicology Letters. 2011;205:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.017. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:1582–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar”, and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2005;43:655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Ashley DL. Supercritical fluid extraction and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry for the analysis of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in cigarettes. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:1303–1308. doi: 10.1021/ac9810821. doi:10.1021/ac9810821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz MR, Shi H, Yang F, Hudmon KS, Jiang H, Chamberlain RM, et al. Case-control study of the D2 dopamine receptor gene and smoking status in lung cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:358–363. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.5.358. doi:10.1093/jnci/90.5.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanov I, Jensen J, Hatsukami D, Hecht SS. New and traditional smokeless tobacco: Comparison of toxicant and carcinogen levels. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1773–1782. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443544. doi:10.1080/14622200802443544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General’s report: The health consequences of involuntary smoking. 1986. Retrieved from www.hhs.gov. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General’s report: The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. 2006. Retrieved from www.hhs.gov. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: Warning about the dangers of tobacco. 2011. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Tobacco use in shisha, studies on the waterpipe smoking in Egypt. Egyptian Smoking Prevention Research Institute and the World Health Organization: Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2006. Publication number 978-92-9021-561-1. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/tfi/pdf/shisha.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Bernert JT, Jain RB, Ashley DL, Pirkle JL. Tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) in smokers in the United States: NHANES 2007–2008. Biomarkers. 2011;16:112–119. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2010.533288. doi:10.3109/1354750X.2010.533288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav JS, Thakur S. Genetic risk assessment in hookah smokers. Cytobios. 2000;101:101–113. Retrieved from www.unboundmedicine.com/medline/ebm/journal/Cytobios. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]