Abstract

A 39-y-old man, who had an episode of pancreatic bleeding due to chronic pancreatitis, received total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation (TP with IAT). Intraoperative ultrasound (US) examination was done to detect transplanted islets and evaluate the quality of US imaging.

Islet isolation from the resected total pancreas was performed and approximately 230,000 islet equivalents (IEQ) (the tissue volume was 600 µL and the purity was 30%) were acquired. A double lumen catheter, used for transplantation and for monitoring the portal vein pressure, was inserted into the portal vein via the superior mesenteric vein, and the tip of the catheter was positioned at the bifurcation of the anterior and posterior branch of the portal vein to selectively infuse the islets into the right lobe of the liver in order to prevent total liver embolization. Intraoperative US examination (central frequency 7.5 MHz, Nemio™ XG, Toshiba Medical System Co.) was started at the same time as the transplantation.

US examination revealed the transplanted islets as hyperechoic clusters that flowed from the tip of the catheter to the periphery of the portal vein. There were no findings of portal thrombosis or bleeding in the US image, and also no increase of the portal vein pressure during transplantation.

In conclusion, we succeeded in visualizing human islets using US, which enabled us to perform islet transplantation safely. The hyperechoic images were considered to be viable islets. Intraoperative US examination can be useful for detecting islets at transplantation in a clinical setting.

Keywords: islet transplantation, ultrasound, chronic pancreatitis, arteriovenous malformation, total pancreatectomy, islet autotransplantation

Introduction

In islet transplantation, the failure of insulin independence is brought about by the loss of islet grafts, caused by instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction, immune rejection, non-specific inflammation or ischemia of the donor islets. Therefore, monitoring the condition of transplanted islets is important for determining whether the islets are viable or damaged, and for selecting the appropriate treatment for preventing graft loss and rescuing patients from severe transplant-related complications. There have been no parameters for evaluating the islet condition except laboratory data including blood glucose and serum C-peptide, but many attempts to visualize the islets have been made for this purpose worldwide. Especially, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)1-3 and positron emission tomography (PET)4,5 are known as useful imaging examinations for detecting islets, not only in rodents but also in humans.

Ultrasound (US) is useful for detecting anatomical and pathological changes in many organs including liver, pancreas, gallbladder, lymph nodes, kidney and gynecological organs. US examination can be performed simply and easily in a short time, with no special preparation required. We focused on US examination for visualizing islets and have attempted to prove the usefulness for this purpose. At first, we performed US examination using diabetic mice that received syngeneic islet transplantation into the renal subcapsular space and detected that the vicinity of transplanted islet grafts could be seen as a hyperechoic area.6 We confirmed that US examination was useful for detecting the location and condition of transplanted islets in an animal model, in spite of the difficulty of individual islet visualization.

Recently, we encountered a patient who received total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation (TP with IAT) and performed intraoperative US examination to detect the islets during transplantation.

Case Report

A 39 y-old man who had an episode of severe abdominal pain and pancreatic bleeding due to chronic pancreatitis (CP) and pancreatic arteriovenous malformation (AVM) was admitted to our institution to undergo TP with IAT. Before hospitalization, he received an elemental diet therapy to prevent CP attack. Although he had no past history and no complication of diabetes, he had episodes of alcohol abuse and smoking. Preoperative serum insulin was 48.3 µU/ml and serum C-peptide was 3.15 ng/mL. Glucose tolerance was at a normal level.

Preoperative CT revealed enriched abnormal vessels (approximately 2.0 cm-sized) in pancreatic head and the portal vein was enhanced at an early stage. It also showed a 2.5 cm cystic lesion in the pancreatic tail, which was suspected to be a pancreatic pseudocyst. The pseudocyst oppressed the posterior wall of the stomach. These image findings indicated AVM, and it was considered that the pancreatitis was caused by AVM. We considered that total pancreatectomy (TP) could not be prevented because there were findings associated with AVM in the pancreatic head and tail. To prevent brittle pancreatic diabetes caused by total islet loss, islet autotransplantation (IAT) was planned at the same time. We already had approval of the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine for the clinical project of TP with IAT.

Before performing TP with IAT for this patient, we had already decided on the procedure to be used follows: (1) a double lumen catheter (for central vein, sized 14 gauze and 30 cm length) was inserted into the portal vein via the superior mesenteric vein for transplantation and monitoring the portal vein pressure, (2) the tip of the catheter was positioned at the bifurcation of the anterior and posterior branch of the portal vein and the islets were selectively infused into the right lobe of the liver to prevent total liver embolization and (3) intraoperative US examination was performed for detecting islets in the portal vein and determining whether the portal vein was embolized or not. The patient had no preoperative events of CP attack or bleeding. After the preoperative examinations, the operation was performed.

In general, en-bloc resection of the pancreas is recommended for islet isolation. However, TP for AVM is technically difficult to perform en-bloc resection due to the existence of many abnormal vessels and pancreatic inflammation. In addition, extensive blood loss is difficult to prevent because the feeding arteries (gastroduodenal artery for the head and splenic artery for the body and tail) must be ligated at the last step of the operation to shorten the warm ischemia time (WIT). Thus, we selected a two-step TP method: distal pancreatectomy (DP) was performed first and then pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) was done to decrease the blood loss and to shorten the WIT. After the exposure of the pancreas, by following the gastroduodenal and common hepatic artery, the root of the splenic artery (SPA) was picked up but not ligated to preserve the blood flow. The pancreatic neck was then separated from the anterior surface of the porto-mesenteric vein. After gentle mobilization of the body and tail of the pancreas and spleen, pancreatic transection in the neck followed by ligation of the splenic vein was performed before ligation of the SPA (final step of the DP). After removal of the distal pancreas, the proximal pancreas with the duodenum was then removed by the standard Whipple’s procedure. The total weight of the pancreas was 86 g. An 8 Fr. size catheter was cannulated into the main pancreatic duct and ductal injection was performed at the procurement site using ET-K solution (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory Inc.). The pancreas was immersed into the cold ET-K solution, packed in a cooler box with crushed ice and carried to the cell-processing center of our institution. After performing TP and tract reconstructions, a double lumen central venous catheter was inserted into the main portal vein via the superior mesenteric vein. The operative time was 670 min and the blood loss volume was 2,070 mL. The WIT was within 10 min and the cold ischemia time was 167 min.

Islets were isolated from the body/tail and head of the pancreas with a semi-circuit digestion system using Liberase MTF-C/T (Roche Diagnostics K.K.). Purification using COBE 2991 was performed in order to reduce the risk of portal embolism and successfully decreased graft volume (600 µL). Two hundred twenty-nine thousand five hundred thirty-eight islet equivalents (IEQs) with the purity of 30% were acquired from the pancreas. The islets were packed in one bag containing 200 mL of heparinized (containing 1,500 units of heparin) transplantation solution. We connected the bag to one side of the portal vein catheter and dripped the islets into the portal vein. The other side of the catheter was connected to a pressure monitor and the portal vein pressure was measured during the whole procedure of transplantation. The portal vein pressure during transplantation was 8–9 mmHg and no elevation was detected. The IAT was finished safely and the transplantation time was 50 min.

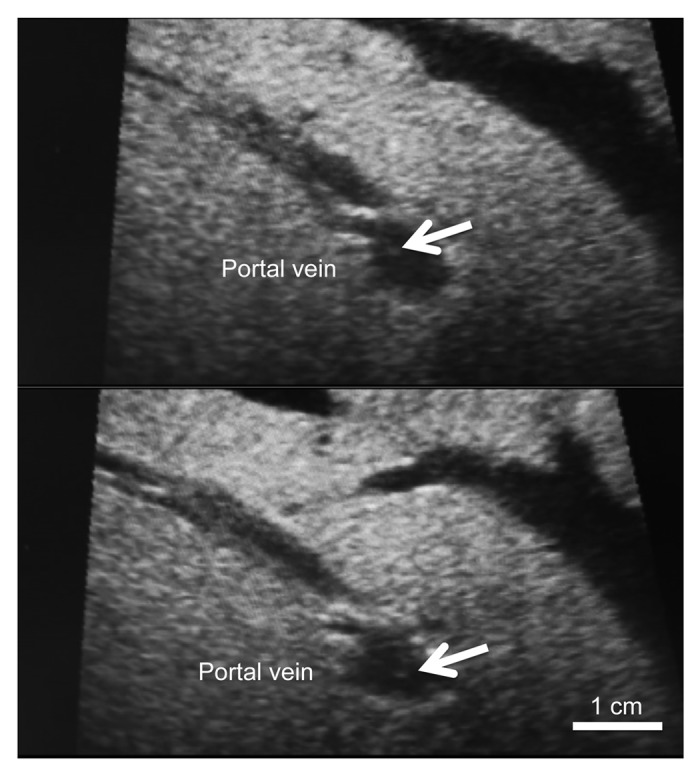

Intraopetative US was done during the IAT using a Diagnostic Ultrasound System (Nemio™ XG, Toshiba Medical System Co.). The central frequency of the US probe was 7.5 MHz. We performed the US examination by putting the probe on the liver directly and confirmed the tip of the catheter, detected as a high echoic tube, at the bifurcation between the anterior and posterior branches of the portal vein. Transplanted islets, which flowed toward the periphery of the portal vein from the tip of the catheter, were visualized as hyperechoic clusters (Fig. 1). No portal thrombosis or bleeding was detected during and after transplantation.

Figure 1. Intraoperative ultrasound findings of the portal vein. The transplanted islets appeared as hyperechoic clusters in the portal vein (arrows).

After finishing the transplantation, the patient was moved to the intensive care unit where he stayed for 3 d. He received intensive insulin therapy (keeping the blood glucose under 130 mg/dL) and was medicated with 0.9 mg / day of GLP-1 analog (Victoza®, Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd.) during admission. He had no adverse events during admission and was discharged with no complications. The insulin doses at discharge were 6 units/day of an ultra-rapid type (Humulin R®, Eli Lilly Japan K.K.) and 7 units/day of a long lasting type (Lebemir®, Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd.). After discharge, his blood glucose and HbA1c levels gradually increased, but he has had no symptoms suggesting hypoglycemia till 1 y after transplantation. The blood glucose, HbA1c and serum C-peptide at 3 mo were 142 mg/dL, 6.5% and 0.31 ng/mL.

Discussion

Visualization of transplanted islets is one of the trends in islet research. It can provide information useful for understanding the islet condition and function when combined with laboratory data including blood glucose and serum C-peptide. The first study about islet visualization was published in 2004, and it showed that intrahepatically transplanted islets labeled by superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), could be detected as low intensity clusters in MRI T2 weighted image using a diabetic rodent model.7 After this study, many preclinical trials have been performed, such as a study about visualizing islet by clinical MRI (standard clinical 1.5-Tesla scanner)8,9 and one using a baboon.10 A clinical trial using MRI in islet transplanted diabetic patients was first performed in 2008,11 and now MRI is a major imaging modality for islet visualization. PET is also an important imaging modality for visualizing islets, and it was recently applied in a clinical setting.5 It is difficult to compare the two examinations since US studies are still rare.6,12 However, we consider that US should be focused on in this area because of its ease and convenience and have tried to demonstrate its effectiveness for detecting islets.

In our previous study, we performed high frequency US examination using diabetic mice that underwent subrenal syngeneic or xenogeneic (rat) islet transplantation.6 Syngeneic islets appeared as a hyperechoic area and the volume of the area was positively correlated with the numbers of transplanted islets. On the other hand, xenogeneic islets were shown as an iso-hypoechoic area, which reflected on the edematous changes due to rejection, and the hypoechoic area diminished and disappeared with a time. In other words, viable islets were shown as a hyperechoic image and damaged islets as a hypoechoic image by US. These results strongly supported that the islet condition could be evaluated by US examination. However, these images reflect the aggregate of islets and not individual islets, and visualization of individual islets is still difficult.

Recently, we have promoted clinical trials of TP with IAT for benign pancreatic disease. To prove the usefulness of US examination for detecting islets in a clinical setting, we performed intraoperative US examination in one CP with AVM patient and evaluated the image. Although US is a convenient and essential imaging examination for deciding the puncture line for percutaneous transhepatic portal cathetarization and is routinely used for islet transplantation in clinical settings,13,14 no studies have mentioned how transplanted islets are visualized in US. We clarified that transplanted human islets could be visualized as hyperechoic clusters in this case report. This finding and our previous data6 clarified some speculations about US imaging for evaluating the islet condition. First, viable islets can be visualized as a hyperechoic image not only in rodent6 but also in human. It is conceivable that islet imaging in intraoperative US (especially echogenicity) can provide reliable information to predict the outcome, success or failure, of the islet transplantation. Second, islets can be visualized not only with high frequency US but also with usual US used for human abdomen (the central frequency was 7.5 MHz) in spite of their tiny structures (within 1 mm diameter). Our data suggest the novel possibility of visualizing islets. By including the present manner of US in deciding the puncture line for percutaneous transhepatic islet transplantation and in detecting some transplant-related complications such as portal thrombosis, hemoperitoneum and hemothorax,14 US can be an essential examination in islet transplantation.

The next step for US is visualization of individual islets as in MRI and PET. Bulte, et al. was the first to succeed in individual islet visualization using a microcapsulation technique.12,15 US studies are still in progress, and further studies are necessary.

This patient received continuous intensive insulin therapy during operation and after transplantation for resting transplanted islets before engraftment. By monitoring blood glucose, diabetologists of our institution managed the dose of insulin following increase of nutrients, and continuous insulin therapy was changed to discontinuous injection when the insulin dose became stable. He needs a little dose of insulin, but had not acquired insulin independence.

TP with IAT has been performed for CP in many islet transplant institutions, especially in the USA. Recently, a reliable systematic review about TP with IAT was published and showed that insulin independence after TP with IAT was 10–64%.16-21 These publications revealed that perfect insulin independence is difficult for current TP with IAT, while this therapy is useful for preventing brittle diabetes due to TP. One of the main reasons is difficulty of islet isolation for CP because of fibrosis and inflammation of pancreas tissue. In our case, he was transplanted insufficient islet numbers (approximately 3,500 IEQ/kg) for insulin independent, but he can prevent unstable diabetic condition due to TP till now. We could accomplish the prevention of hypoglycemia in this case, but believe that further improvements of our protocol are necessary to promote this therapy.

In conclusion, our intraoperative US examination could visualize transplanted islets as hyperechoic clusters and was useful to confirm that islets were successfully transplanted into the liver with no complications. Intraoperative US examination can be useful for detecting islets during transplantation in the clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

We thank all medical and co-medical staffs involved with treating the patient in surgery, managing pre- and postoperative course, islet isolation and transplantation and controlling blood glucose. This study is supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technology of Japan (Challenging Exploratory Research: 24659582) and the Takeda Science Foundation (N.S.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AVM

arteriovenous malformation

- CP

chronic pancreatitis

- DP

distal pancreatectomy

- IEQ

islet equivalents

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PD

pancreaticoduodenectomy

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPA

splenic artery

- SPIO

superparamagnetic iron oxide

- TP with IAT

total pancreatectomy with islet autotransplantation

- US

ultrasound

- WIT

warm ischemia time

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/islets/article/22384

References

- 1.Kriz J, Jirak D, Berkova Z, Herynek V, Lodererova A, Girman P, et al. Detection of pancreatic islet allograft impairment in advance of functional failure using magnetic resonance imaging. Transpl Int. 2012;25:250–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evgenov NV, Medarova Z, Dai G, Bonner-Weir S, Moore A. In vivo imaging of islet transplantation. Nat Med. 2006;12:144–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saudek F, Jirák D, Girman P, Herynek V, Dezortová M, Kríz J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pancreatic islets transplanted into the liver in humans. Transplantation. 2010;90:1602–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ffba5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Y, Dang H, Middleton B, Zhang Z, Washburn L, Stout DB, et al. Noninvasive imaging of islet grafts using positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11294–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603909103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson O, Eich T, Sundin A, Tibell A, Tufveson G, Andersson H, et al. Positron emission tomography in clinical islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2816–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakata N, Kodama T, Chen R, Yoshimatsu G, Goto M, Egawa S, et al. Monitoring transplanted islets by high-frequency ultrasound. Islets. 2011;3:259–66. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.5.17058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jirák D, Kríz J, Herynek V, Andersson B, Girman P, Burian M, et al. MRI of transplanted pancreatic islets. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1228–33. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai JH, Foster P, Rosales A, Feng B, Hasilo C, Martinez V, et al. Imaging islets labeled with magnetic nanoparticles at 1.5 Tesla. Diabetes. 2006;55:2931–8. doi: 10.2337/db06-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malosio ML, Esposito A, Poletti A, Chiaretti S, Piemonti L, Melzi R, et al. Improving the procedure for detection of intrahepatic transplanted islets by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2372–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medarova Z, Vallabhajosyula P, Tena A, Evgenov N, Pantazopoulos P, Tchipashvili V, et al. In vivo imaging of autologous islet grafts in the liver and under the kidney capsule in non-human primates. Transplantation. 2009;87:1659–66. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a5cbc0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toso C, Vallee JP, Morel P, Ris F, Demuylder-Mischler S, Lepetit-Coiffe M, et al. Clinical magnetic resonance imaging of pancreatic islet grafts after iron nanoparticle labeling. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:701–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arifin DR, Long CM, Gilad AA, Alric C, Roux S, Tillement O, et al. Trimodal gadolinium-gold microcapsules containing pancreatic islet cells restore normoglycemia in diabetic mice and can be tracked by using US, CT, and positive-contrast MR imaging. Radiology. 2011;260:790–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owen RJ, Ryan EA, O’Kelly K, Lakey JR, McCarthy MC, Paty BW, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic pancreatic islet cell transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus: radiologic aspects. Radiology. 2003;229:165–70. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2291021632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venturini M, Angeli E, Maffi P, Fiorina P, Bertuzzi F, Salvioni M, et al. Technique, complications, and therapeutic efficacy of percutaneous transplantation of human pancreatic islet cells in type 1 diabetes: the role of US. Radiology. 2005;234:617–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342031356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett BP, Ruiz-Cabello J, Hota P, Liddell R, Walczak P, Howland V, et al. Fluorocapsules for improved function, immunoprotection, and visualization of cellular therapeutics with MR, US, and CT imaging. Radiology. 2011;258:182–91. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bramis K, Gordon-Weeks AN, Friend PJ, Bastin E, Burls A, Silva MA, et al. Systematic review of total pancreatectomy and islet autotransplantation for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99:761–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toledo-Pereyra LH. Islet cell autotransplantation after subtotal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1983;118:851–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1983.01390070059012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valente U, Arcuri V, Barocci S, Bonafini E, Costigliolo G, Dardano G, et al. Islet and segmental pancreatic auto-ransplantation after pancreatectomy - Follow-up of 25 patients for up to 5 years. Transplant Proc. 1985;17:363–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, Wray CJ, D’Alessio D, Choe KA, James LE, et al. Factors associated with insulin and narcotic independence after islet autotransplantation in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:680–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutherland DE, Gruessner AC, Carlson AM, Blondet JJ, Balamurugan AN, Reigstad KF, et al. Islet autotransplant outcomes after total pancreatectomy: a contrast to islet allograft outcomes. Transplantation. 2008;86:1799–802. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819143ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcea G, Weaver J, Phillips J, Pollard CA, Ilouz SC, Webb MA, et al. Total pancreatectomy with and without islet cell transplantation for chronic pancreatitis: a series of 85 consecutive patients. Pancreas. 2009;38:1–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181825c00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]