Abstract

Introduction

We sought to determine the efficacy of using both irinotecan- and etoposide-containing regimens sequentially for patients with untreated limited stage small cell lung cancer (LS-SCLC).

Methods

Patients with untreated, measurable LS-SCLC, performance status 0–2, and adequate organ function were eligible. Treatment consisted of induction with cisplatin 30 mg/m2 and irinotecan 65 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1 and 8 every 21 days for two cycles. Beginning day 43, daily chest irradiation to 70 Gy was administered concurrently with carboplatin AUC 5 day 1 and etoposide 100 mg/m2 days 1 to 3 every 21 days for 3 cycles. The primary objective was to differentiate between 45% and 60% 2-year survival.

Results

Two induction cycles were delivered to 72 of 75 (96%) eligible patients and all planned treatment was delivered to 59 patients (79%). Cisplatin and irinotecan induction chemotherapy resulted in complete responses in 7% and partial responses 64% (response rate 71%; 95% CI 59–81%). The best response to all therapy included 88% complete or partial responses (95% CI for 78–94%). With median follow-up of 57 months, the median progression-free survival and overall survival are 12.6 (95% CI 9.4–14.7) and 18.1 months (15.8–22.9), respectively. The 1- and 2-year survival was 69% and 31%, respectively. Frequent (>20%) grade 3 and 4 toxicities were neutropenia 84%, hemoglobin 36%, platelets 51%, esophagitis (22%) and dehydration in 24%. There were no fatal toxicities.

Conclusions

This treatment regimen of irinotecan-cisplatin induction chemotherapy followed by 70 Gy concurrent radiation and etoposide-carboplatin has tolerable toxicity but did not meet the pre-planned 2-year survival target for further development.

Keywords: small cell lung cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, topoisomerase inhibitor

Introduction

Approximately 13% of lung cancer is the small cell (SCLC) histological type, which is characterized by initial sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy.1 Chemotherapy improves overall survival by more than four-fold, and the addition of thoracic radiotherapy further improves both local tumor control and survival for patients with limited stage SCLC, resulting in 2-year survival of approximately 45% in clinical trials.2 However, most patients with limited stage SCLC eventually succumb to recurrent disease.

The camptothecin, irinotecan (CPT-11), is a prodrug metabolized by carboxylesterase to an active metabolite, SN-38, which inhibits topoisomerase I.3 Irinotecan has single agent activity in previously treated SCLC.4 A Japanese phase III study of cisplatin and irinotecan in patients with extensive stage SCLC resulted in an improvement of 3 months in median survival compared to standard cisplatin and etoposide.5 We conducted a phase II study incorporating irinotecan as well as the topoisomerase II inhibitor, etoposide, into the initial treatment regimen of patients with untreated limited stage SCLC to determine whether the addition of irinotecan resulted in preliminary evidence of improved outcome.

Methods

Patients

Patients with histologically or cytologically documented small cell lung cancer of limited stage and measurable disease were eligible for the study. Limited stage was defined as disease restricted to one hemithorax with regional lymph node metastases, including hilar, ipsilateral and contralateral mediastinal lymph nodes. Patients with clinically suspected or confirmed supraclavicular lymph node metastases, patients with pathologically enlarged contralateral hilar lymph nodes, and patients with pleural effusions visible on plain chest radiographs, whether cytologically positive or not, were not eligible. Other requirements included age of at least 18 years, ECOG performance status 0 to 2, no active second malignancy, non pregnant and not breast feeding, neutrophil count at least 1500/uL, platelets count at least 100,000/uL, serum creatinine less than the upper limit of normal, bilirubin no greater than 1.5 mg/dL, and serum aspartase aminotransferase less than 2 times the upper limit of normal.

Within 28 days before study registration on the study, patients had a physical examination, radiographic imaging for baseline tumor measurement, complete blood count, serum chemistries (creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin). Patients also had a chest radiograph, bone scan, CT or MRI scan of the chest and upper abdomen, and CT or MRI of the brain within 42 days prior to registration. Each participant signed an IRB-approved, protocol-specific informed consent in accordance with federal and institutional guidelines.

Treatment

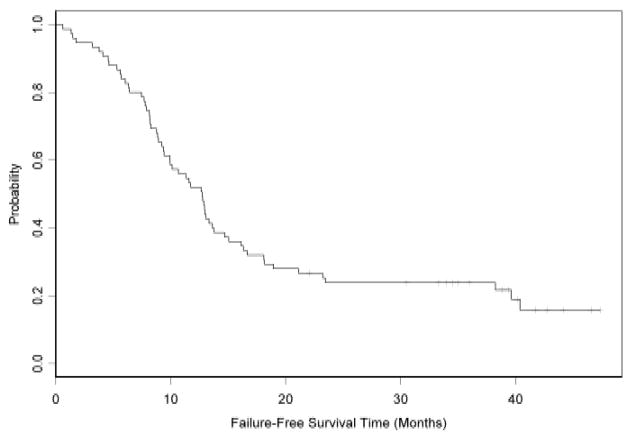

The schema of study-required treatment is shown in Figure 1. Induction chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin 30 mg/m2/day on days 1 and 8 and irinotecan 65 mg/m2/day on days 1 and 8 for two cycles of 21 days each. Consolidation chemotherapy followed immediately after induction and consisted of three 21-day cycles of carboplatin AUC 5 (using the Calvert formula) on day 1, and etoposide 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 3. A cycle of chemotherapy (day 1) was delayed up to 3 weeks if the neutrophils were less than 1500/uL or platelets were less than 100,000 uL; patients with longer duration of neutropenia or thrombocytopenia were to be removed from study treatment. Prophylactic granulocyte growth factor use was discouraged but permitted when used per ASCO guidelines.6 Erythrocyte stimulating agents were allowed, but discouraged during chest radiotherapy.

Figure 1.

Schema of Study.

Chest radiotherapy began concurrently with consolidation chemotherapy and was administered to all patients without evidence of progression of disease outside the planned radiation port. Radiotherapy with standard or conformal technique was allowed but IMRT was prohibited. The total dose was 70 Gy delivered in 2 Gy fractions; an initial 44 Gy was given to the original tumor volume (determined on a chest CT scan after induction chemotherapy) and potential occult disease sites (ipsilateral hilar, subcarinal, and bilateral mediastinal lymph nodes) followed by a 26 Gy boost to only the original tumor volume. A single radiation field with margins of 1–2 cm around target volumes was used. Patients achieving a complete response or a very good partial response as determined by the treating physician after completion of chemotherapy and chest radiotherapy were recommended to receive prophylactic cranial irradiation starting 3 to 5 weeks after completion of chemotherapy.

Dose modifications

Modification of induction chemotherapy day 8 doses for neutropenia or thrombocytopenia were: for grade 2, reduction of irinotecan by 10 mg/m2 and cisplatin by 5 mg/m2; for grade 3 and 4, omission of day 8 chemotherapy. Febrile neutropenia led to a 25% reduction of both drugs in subsequent cycles, however, all patients received full doses of drugs in the first cycle of consolidation unless febrile neutropenia occurred in both cycles of induction chemotherapy. Grade 4 thrombocytopenia resulted in a 25% reduction of subsequent drugs.

Irinotecan was omitted on day 8 if diarrhea was present. The second cycle of cisplatin-irinotecan was delayed if diarrhea was present on cycle 2 day 1; diarrhea continuing beyond two weeks resulted in continuation of cisplatin without irinotecan. Grade 2 or 3 diarrhea in cycle 1 resulted in reduction of irinotecan to 55 mg/m2 and grade 4 led to treatment with cisplatin alone.

A cycle of chemotherapy was delayed if creatinine was over 2.0 mg/dL while day 8 chemotherapy was reduced (cisplatin 67% for creatinine ULN to 2.0; cisplatin omitted and etoposide 50% for creatinine 2.1 to 3.0; and delayed for creatinine over 3). Cisplatin or carboplatin was reduced by 25% for grade 2 neurotoxicity that recovered to grade 1 or better and omitted for more severe toxicity. Treatment breaks in radiotherapy were discouraged and required discussion with the radiation co-chair.

Outcome assessment and statistical methods

Tumor response was assessed using RECIST version 1.0.7 Toxicity was assessed using NCI-CTC version 3.0. Survival time was measured from the day of registration until date of death; living patients were censored at the date of last follow-up examination. Progression-free survival was measured from the day of registration until disease progression or death. The method of Kaplan-Meier was used to describe survival and progression-free survival. The primary endpoint of the study was based on the proportion of patients who are alive 2 years after initiation of protocol therapy. The study was designed to differentiate between a 45% and 60% 2-year survival rate. A one-stage phase II design was used. A sample size of 75 would provide 90% power to differentiate 2-year survival rates of 45% or less and 60% or greater, with a one-sided type I error of 0.091. Secondary objectives were to assess the response rates to induction and overall therapy, overall and progression-free survival, and toxicity. Patient registration and data collection were managed by the CALGB Statistical Center. Data quality was ensured by careful review of data by CALGB Statistical Center staff and by the study chairperson. Statistical analyses were performed by CALGB statisticians.

Results

Patients

Seventy-eight patients were enrolled between November 15, 2003 and September 30, 2005. Three patients were ineligible due to the presence of metastatic disease at the time of enrollment; these patients are excluded from the efficacy analyses but included in the toxicity assessment. Characteristics of the 75 eligible patients are shown in Table 1. Fifty-nine patients (79%) completed all protocol therapy. Reasons for not completing treatment included progression of disease (n=5), toxicity (n=4), patient refusal (n=4), death (n=2), and removal from treatment by treating radiation oncologist due to concern of potential toxicity of the radiation protocol treatment (n=1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible patients (n=75).

| Gender: | |||

| Male | 42 | 56% | |

| Female | 33 | 44% | |

| Age: | Median = 61 | ||

| Range (min, max)= (41, 79) | |||

| 40–49 | 11 | 15% | |

| 50–59 | 19 | 25% | |

| 60–69 | 29 | 39% | |

| 70–79 | 16 | 21% | |

| Race: | |||

| White | 73 | 97% | |

| Black | 2 | 3% | |

| Performance status: | |||

| 0 | 49 | 65% | |

| 1 | 26 | 35% | |

| Weight loss: | |||

| 0% to <5% | 64 | 85% | |

| 5% to <10% | 4 | 5% | |

| >= 10% | 6 | 8% | |

| Missing Data | 1 | 1% | |

Response

Tumor response evaluation is summarized in Table 2. The best response to the two cycles of induction cisplatin-irinotecan chemotherapy was complete response, partial response, and stable disease in 5 (7%), 48 (64%), and 13 (17%), respectively. One patient had progression, 7 were unevaluable, and there was one death during the first 6 weeks on study due to aspiration. Thus, the overall response rate to induction was 71% (95% CI 59–81%). The overall response rate at the completion of all protocol therapy was 88% (95% CI 78–94%) with compete response, partial response, and stable disease in 28 (37%), 38 (51%), and 6 (8%) of patients, respectively. One patient each had progressive disease, an unevaluable response, and death due to other causes.

Table 2.

Best Tumor Response to Treatment (n=75).

| Response | Induction | Overall |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Response | 5 (7%) | 28 (37%) |

| Partial Response | 48 (64%) | 38 (51%) |

| Stable Disease | 13 (17%) | 6 (8%) |

| Progression | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Unevaluable | 7 (9%) | 1 (1%) |

| Early Death (aspiration day 19) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Overall Response Rate (95% CI) | 71% (59–81%) | 88% (78–94%) |

Survival

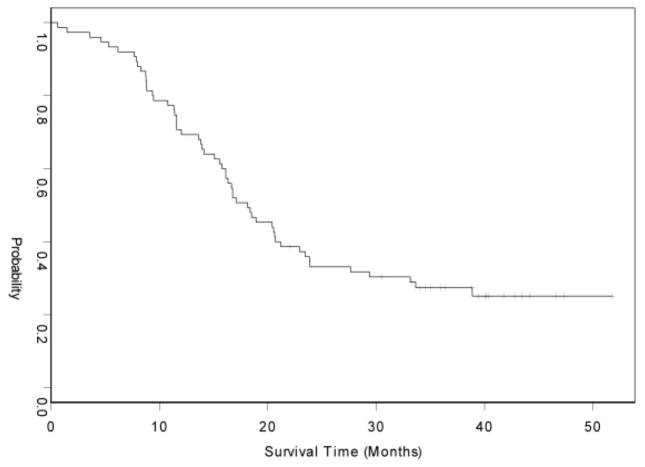

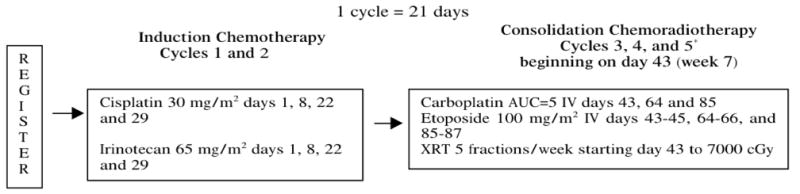

After a median follow-up time of 57 months, 64 patients had progressed and 61 had died. The median progression-free survival was 12.6 months (95% CI: 9.4 to 14.7 months) and the median overall survival was 18.1 months (95% CI: 15.8 to 22.9 months) (Table 3; and Figures 2 and 3). Only 23 (31%) patients were alive at year two.

Table 3.

Progression-Free and Overall Survival (n=75)

| Failures/Deaths (n) | 1-Year Survival (%; 95% C.I.) | 2-Year Survival (%; 95% C.I.) | Median (95% C.I.) (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | 61 | 69% (61–81%) | 31% (22–43%) | 18.1 (15.8–22.9) |

| Progression-free Survival | 64 | 49% (39–62%) | 20% (13–31%) | 12.6 (9.4–14.7) |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of Progression-Free Survival.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve of Overall Survival.

Recurrence

Four patients had relapsed during radiation therapy; 1(25%) patient relapsed at both local and distant sites at the same time and 3(75%) patients had distant relapse only. Of the 40 patients who had relapse during the follow-up period, 12 (30%) patients relapsed at both local and distant sites the same time; 1(3%) patient had distant relapse first, then later relapsed locally; 8(20%) patients has local relapse only; and 19(48%) patients had distant relapse only. Overall, 23 of 37 (62%) of patients had relapse outside both the radiation field and outside the pre-chemotherapy tumor volume.

Toxicity

All 78 patients enrolled patients were available for some toxicity evaluation including 76 patients evaluable for toxicity during the two cycles of induction chemotherapy and 72 patients during the consolidation therapy with combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Table 4). Only 3 patients (4%) had diarrhea of at least grade 3 during induction therapy. Similarly, there were infrequent hematologic adverse events during induction therapy with only 15 patients (19%) experiencing any grade 3 or 4 hematologic adverse event. Overall, 20 (26%) patients had any grade 3 or 4 adverse event during induction therapy.

Table 4.

Adverse Events (AEs) of Grade 3 or 4 Severity and at Least 10% Incidence during Induction (n=76), Consolidation (n=72), and Overall Therapy (n=78).

| Induction Grade, n (%) | Consolidation Grade, n (%) | Overall Grade, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Toxicity | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Hematologic AEs | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (36%) | 0 (0%) |

| Leukocytes | 4 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 30 (42%) | 29 (40%) | 32 (41%) | 29 (37%) |

| Lymphopenia | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (7%) | 5 (7%) | 7 (9%) | 5 (6%) |

| Neutrophils | 11 (14%) | 3 (4%) | 14 (19%) | 46 (64%) | 19 (24%) | 47 (60%) |

| Platelets | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 19 (26%) | 20 (28%) | 19 (24%) | 21 (27%) |

| Maximum Hematologic AE | 11 (14%) | 4 (5%) | 10 (14%) | 54 (75%) | 12 (15%) | 56 (72%) |

| Non-Hematologic AEs | ||||||

| Fatigue | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (14%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dehydration | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 17 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (23%) | 1 (1%) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (8%) | 1 (1%) |

| Dysphagia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (17%) | 0 (0%) |

| Esophagitis | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (19%) | 2 (3%) | 15 (19%) | 2 (3%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 9 (12%) | 2 (3%) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pain | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (13%) | 1 (1%) | 11 (14%) | 1 (1%) |

| Maximum Non-Hematologic AE | 9 (12%) | 1 (1%) | 31 (43%) | 8 (11%) | 37 (47%) | 9 (12%) |

| Maximum Overall AE | 16 (21%) | 4 (5%) | 12 (17%) | 55 (76%) | 14 (18%) | 57 (73%) |

In contrast, during consolidation, 64 patients (89%) had grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicity. However, only 3 (4%) required transfusion and only 10 (14%) had febrile neutropenia. Esophagitis occurred in 16 (21%) patients and was grade 3 in all but 2 patients. Other non-hematologic adverse events occurring during consolidation were fatigue in 9 (13%), dehydration in 17 (24%), hypokalemia in 7 (10%), dysphagia in 13 (18%), and pain in 10 (14%); all were grade 3 except one patient who had grade 4 pain. Overall, non-hematologic grade 3 or 4 adverse events during consolidation therapy occurred in 31 (43%) and 8 (11%) patients, respectively.

Overall during all therapy, hematological and non-hematological adverse events of grade 3 or 4 occurred in 14 (18%) and 57 (73%) patients, respectively. As with adverse events observed during induction and consolidation therapy, the hematological toxicity was mostly asymptomatic and without febrile neutropenia or need for transfusion. Diarrhea occurred in 7 (9%) patients during therapy. For the most commonly observed grade 3 or 4 toxicity, the rate of completing treatment was not different between those with and without dehydration (Fisher’s exact test p=0.75). No patients died as a result of an adverse event from therapy.

Discussion

Treatment of patients with extensive stage SCL with cisplatin and irinotecan in the phase III trial by the Japanese Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG 9511) resulted in a longer median overall survival by 3.4 months compared with survival of those treated with cisplatin and etoposide,5 which has been a standard first line treatment for patients with SCLC for several decades. However, two larger studies conducted in North America have found divergent results. Hanna et al used an alternate dosing regimen of cisplatin and irinotecan with three week cycle length8 and SWOG S0124 used an identical chemotherapy doses and schedule as (JCOG9511).9 In neither North American study was there a statistically significant difference in overall survival between the etoposide arm and the irinotecan arm.8, 9 Recently, a meta-analysis of these three studies plus a fourth phase III study using combinations of irinotecan and etoposide with carboplatin in extensive stage SCLC10 showed an improved overall survival of irinotecan-platinum over etoposide-platinum with a hazard ratio of 0.81 (95% CI 0.66–0.99; p=0.044).11 However, the study of carboplatin-based combinations used oral etoposide, which has previously been shown to result in inferior survival12 or greater toxicity13 compared to intravenous etoposide in SCLC. When only the three phase III studies comparing cisplatin-irinotecan to cisplatin-etoposide were included in the meta-analysis, the hazard ratio continued to favor cisplatin-irinotecan but was not statistically significant (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.67–1.07).11 Two European studies of either cisplatin14 or carboplatin15 combinations with irinotecan versus a combination with etoposide both non-statistically significantly favored the irinotecan arm with hazard ratios of 0.81 (95% CI 0.65–1.01; p=0.06) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.54–1.03; p=0.07), respectively. Thus, if there is improvement in survival with the use of irinotecan combination chemotherapy in first line treatment of extensive stage SCLC it is small. Differences in efficacy and toxicity of irinotecan-containing regimens in these three studies might also have resulted from genetic differences in the populations studied, such as the UGT1A1 polymorphism associated with increased toxicity from high doses of irinotecan.16

In limited stage SCLC, the addition of chest radiotherapy to chemotherapy results in improved overall survival with the best outcome observed when radiotherapy is given concurrently with chemotherapy.17, 18 However, concurrent administration of irinotecan during radiotherapy results in toxicity limiting the dose of irinotecan to less than full dose tolerated without radiotherapy. In SCLC, some studies have attempted to administered chest radiotherapy and irinotecan-containing chemotherapy concurrently to patients with limited stage SCLC. Two dose escalation studies of irinotecan given concurrently with cisplatin and chest radiotherapy demonstrated tolerability when used with either split course chest radiotherapy19 or standard daily fractionation,20 although the recommended irinotecan dose varied between the studies. In contrast, a Dutch dose escalation study administering cisplatin and irinotecan in a single dose once every three weeks resulted in excessive radiation-associated toxicity.21 In a multisite phase II study of two cycles of induction cisplatin-irinotecan followed by weekly irinotecan with concurrent chest radiotherapy, only 56% of patients were able to receive the full planned treatment.22 Two small, single institution phase II studies of cisplatin-irinotecan chemotherapy, in which the irinotecan dose was approximately 66% of full dose without radiotherapy, combined with chest radiotherapy confirmed tolerability but each had a nearly identical median survival of 20 months.23, 24 A third single institution study of 37 patients using a similar design had a median survival of 26 months.25

An alternative approach to concurrent irinotecan and radiation is sequential therapy with an alternative chemotherapy being administered during radiation. Two early phase Japanese studies used nearly identical treatment schemata consisting of cisplatin and etoposide for one cycle with twice daily chest radiotherapy followed by three cycles of cisplatin and irinotecan chemotherapy have been completed.26, 27 The response rates were 88% to 97% and median survival times were 20 and 23 months. These results were the basis of a phase III study by the Japanese Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG 0202), which has preliminarily been reported to show no difference between the irinotecan and etoposide arms (HR=1.085, 95% CI 0.80–1.46; p=0.70).28 A single-institution Korean phase II study using the opposite order of regimens (two cycles of cisplatin and irinotecan followed by two cycles of cisplatin and etoposide with 45 Gy twice daily chest radiotherapy) also demonstrated efficacy with a response of 97% and medial survival of 25 months.29

Our study also used a sequential approach and built upon two prior CALGB studies that examined paclitaxel and topotecan with filgrastim (CALGB 39808)30 or paclitaxel-topotecan-etoposide with filgrastim (CALGB 30002)31 for the first two cycles of chemotherapy followed by three cycles of carboplatin-etoposide with 70 Gy chest radiation in single daily fractions. The use of a similar design in the current study allowed us to indirectly compare results from the current study with the prior, similarly designed studies, as well as evaluate the activity of cisplatin irinotecan in untreated limited stage SCLC. The overall survival was shorter in the current study (18 months) compared to CALGB 39808 (22 months) and CALGB 30002 (20 months) despite using identical chemoradiotherapy after the first two cycles of chemotherapy and having similar characteristics of the enrolled patients. A subset of 26 patients in CALGB 30002 had data on location of relapse, of whom 58% had relapse outside both the radiation field and the prechemotherapy tumor volume, similar to the rate of distant relapse observed in this trial (62%). In addition to using daily radiotherapy fractionation, these three CALGB studies all began chest radiotherapy concurrent with the third cycle of chemotherapy, which has been suggested to contribute to accelerated repopulation and poorer outcome relative to earlier initiation of chest radiotherapy.32 However, a recently reported phase III study comparing initiation of concurrent chemoradiotherapy on the first or third cycle showed no difference in overall survival.33

The response rate after two cycles of cisplatin irinotecan in our study (71%) was similar to the 64% response rate reported among 61 patients in a phase II study of carboplatin-irinotecan in patients with anatomically limited disease who were not fit to receive chest radiotherapy.34 Not unexpectedly, the overall survival was longer in our study (18.1 months versus 13.8 months).34 However, the two year survival rate of 31% fell well short of the predetermined target of 60% to justify further investigation of the treatment studied here. Although the predetermined target might be overly ambitious and the toxicity of the treatment regimen was manageable, there is insufficient efficacy to support either the use of this treatment in clinical practice or further investigation.

New strategies for augmenting median and overall survival among patients with limited stage SCLC are needed. To that end, the current phase III intergroup study for limited stage SCLC (CALGB 30610) is comparing once daily chest radiotherapy to 70 Gy as used in this study to two other chest radiation dosing plans. Several recent therapeutic advances in cancers other than SCLC have exploited specific somatically acquired genetic defects targeted by small molecule inhibitors, such as erlotinib and crizotinib in non-SCLC and vemurafenib in melanoma. In contrast, SCLC contains a large number of genetic alterations35 so that identifying and therapeutically modulating the key targets has proven difficult. In addition to targeted agents, new treatment approaches such as novel cytotoxic agents and refinements in radiotherapy show promise for improvement in outcome for patients with SCLC.36

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute; grant CA033601)

We thank patients and their families for participating in this study, all CALGB investigators and research staff, and Marguerite Adkins for administrative assistance. Funding was received from National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health National to Cancer and Leukemia Group B (grant number CA033601). Michael Kelley is the recipient of a Merit Review Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez E, Lilenbaum RC. Small cell lung cancer: past, present, and future. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chabot GG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:245–259. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199733040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda N, Fukuoka M, Kusunoki Y, et al. CPT-11: a new derivative of camptothecin for the treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1225–1229. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.8.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:85–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozer H, Armitage JO, Bennett CL, et al. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology Growth Factors Expert Panel. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3558–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna N, Bunn PA, Jr, Langer C, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2038–2043. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lara PN, Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2530–2535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hermes A, Bergman B, Bremnes R, et al. Irinotecan plus carboplatin versus oral etoposide plus carboplatin in extensive small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4261–4267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing irinotecan/platinum with etoposide/platinum in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:867–873. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e3181d95c87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girling DJ. Comparison of oral etoposide and standard intravenous multidrug chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer: a stopped multicentre randomised trial. Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party. Lancet. 1996;348:563–566. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller AA, Herndon JE, 2nd, Hollis DR, et al. Schedule dependency of 21-day oral versus 3-day intravenous etoposide in combination with intravenous cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III study of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1871–1879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zatloukal P, Cardenal F, Szczesna A, et al. A multicenter international randomized phase III study comparing cisplatin in combination with irinotecan or etoposide in previously untreated small-cell lung cancer patients with extensive disease. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1810–1816. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmittel A, Sebastian M, Fischer von Weikersthal L, et al. A German multicenter, randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan-carboplatin with etoposide-carboplatin as first-line therapy for extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1798–1804. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Innocenti F, Undevia SD, Iyer L, et al. Genetic variants in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 gene predict the risk of severe neutropenia of irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1382–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small- cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1628–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warde P, Payne D. Does thoracic irradiation improve survival and local control in limited-stage small-cell carcinoma of the lung? A meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:890–895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oka M, Fukuda M, Kuba M, et al. Phase I study of irinotecan and cisplatin with concurrent split-course radiotherapy in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1998–2004. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klautke G, Fahndrich S, Semrau S, et al. Simultaneous chemoradiotherapy with irinotecan and cisplatin in limited disease small cell lung cancer: a phase I study. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jong WK, de Jonge MJ, van der Leest AH, et al. Irinotecan and cisplatin with concurrent thoracic radiotherapy in a once-every-three-weeks schedule in patients with limited-disease small-cell lung cancer: a phase I study. Lung Cancer. 2008;61:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda K, Negoro S, Tanaka M, et al. A phase II study of cisplatin and irinotecan as induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant thoracic radiotherapy with weekly low-dose irinotecan in unresectable, stage III, non-small cell lung cancer: JCOG 9706. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 2011;41:25–31. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong HC, Lee SY, Kim JH, et al. Phase II study of irinotecan plus cisplatin with concurrent radiotherapy for the patients with limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelwahab S, Abdulla H, Azmy A, et al. Integration of irinotecan and cisplatin with early concurrent conventional radiotherapy for limited-disease SCLC (LD-SCLC) Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:230–236. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohn JH, Moon YW, Lee CG, et al. Phase II trial of irinotecan and cisplatin with early concurrent radiotherapy in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:1845–1950. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kubota K, Nishiwaki Y, Sugiura T, et al. Pilot study of concurrent etoposide and cisplatin plus accelerated hyperfractionated thoracic radiotherapy followed by irinotecan and cisplatin for limited-stage small cell lung cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group 9903. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5534–5538. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saito H, Takada Y, Ichinose Y, et al. Phase II study of etoposide and cisplatin with concurrent twice-daily thoracic radiotherapy followed by irinotecan and cisplatin in patients with limited-disease small-cell lung cancer: West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group 9902. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5247–5252. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubota K, Hida T, Ishikura S, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing etoposide and cisplatin (EP) with irinotecan and cisplatin (IP) following EP plus concurrent accelerated hyperfractionated thoracic radiotherapy (EP/AHTRT) for the treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer (LD-SCLC): JCOG0202. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):abstr 7028. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han JY, Cho KH, Lee DH, et al. Phase II study of irinotecan plus cisplatin induction followed by concurrent twice-daily thoracic irradiation with etoposide plus cisplatin chemotherapy for limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3488–3494. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogart JA, Herndon JE, 2nd, Lyss AP, et al. 70 Gy thoracic radiotherapy is feasible concurrent with chemotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer: analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 39808. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller AA, Wang XF, Bogart JA, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel-topotecan-etoposide followed by consolidation chemoradiotherapy for limited-stage small cell lung cancer: CALGB 30002. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:645–651. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318074bbf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Ruysscher D, Pijls-Johannesma M, Bentzen SM, et al. Time between the first day of chemotherapy and the last day of chest radiation is the most important predictor of survival in limited-disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1057–1063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park K, Sun J-M, Kim S-W, et al. Phase III trial of concurrent thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) with either the first cycle or the third cycle of cisplatin and etoposide chemotherapy to determine the optimal timing of TRT for limited-disease small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):abstr 7004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laack E, Thom I, Krull A, et al. A phase II study of irinotecan (CPT-11) and carboplatin in patients with limited disease small cell lung cancer (SCLC) Lung Cancer. 2007;57:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pleasance ED, Stephens PJ, O’Meara S, et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature. 2010;463:184–190. doi: 10.1038/nature08629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metro G, Cappuzzo F. Emerging drugs for small-cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:591–606. doi: 10.1517/14728210903206983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]