Abstract

The bacterial genera Escherichia, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio, Yersinia and Francisella include important food safety and biothreat agents causing food-related and other human illnesses worldwide. We aimed to develop rapid methods with the capability to simultaneously and differentially detect all six pathogens in one run. Our initial experiments to use previously reported sets of primers revealed non-specificity of some of the sequences when tested against a broader array of pathogens, or proved not optimal for simultaneous detection parameters. By extensive mining of the whole genome and protein databases of diverse closely and distantly related bacterial species and strains, we have identified unique genome regions, which we utilized to develop a detection platform. Twelve of the specific genomic targets we have identified to design the primers in F. tularensis ssp. tularensis, F. tularensis ssp. novicida, S. dysentriae, S. typhimurium, V. cholera, Y. pestis, and Y. pseudotuberculosis contained either hypothetical or putative proteins, the functions of which have not been clearly defined. Corresponding primer sets were designed from the target regions for use in real-time PCR assays to detect specific biothreat pathogens at species or strain levels. The primer sets were first tested by in-silico PCR against whole genome sequences of different species, sub-species, or strains and then by in vitro PCR against genomic DNA preparations from 23 strains representing six biothreat agents (E.coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933, Shigella dysentriae, Salmonella typhi, Francisella tularensis ssp. tularensis, Vibrio cholera, and Yersinia pestis) and six foodborne pathogens (Salmonella typhimurium, Salmonella saintpaul, Shigella sonnei, Francisella novicida, Vibrio parahemolytica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis). Each pathogen was specifically identifiable at the genus and species levels. Sensitivity assays performed using purified DNA showed the lowest detection limit of 640 fg DNA/µl for F. tularensis. A preliminary test done to detect Shigella organisms in a milk matrix showed that 6–60 colony forming units of the bacterium per milliliter of milk could be detected in about an hour. Therefore, we have developed a platform to simultaneously detect foodborne pathogen and biothreat agents specifically and in real-time. Such a platform could enable rapid detection or confirmation of contamination by these agents.

Keywords: Biothreat agents, PCR, food-borne pathogens

1. Introduction

Food-borne pathogens cause millions of clinical illnesses every year and cost billions of dollars to manage and control. Intentional contamination of food in the form of a biological attack is an even more alarming prospect given that no standards or established routines exist to test food for these threats (Kennedy, 2008). Intentional contamination could involve among many food products, contamination of water, milk, and other beverages that are distributed from bulk storage or processing sites, not necessarily at the source of the starting product. This has the potential to result in disastrous and far-reaching effects, including direct morbidity and/or mortality, disruption of food distribution, loss of consumer confidence in government and the food supply, business failures, trade restrictions, and ripple effects on the economy (Busta and Shaun, 2011). Therefore, from both food safety and biothreat points of view, it is imperative that food and drink contaminations are detected well before they reach the consumer level.

In the past decades the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) has been transformed into a powerful tool to detect pathogens with extremely high sensitivity and specificity. While the main drawback of PCR still remains to be the inability to distinguish between live and dead organisms, the potential for non-specific detection could also be high if the target sequences are not specific or of contamination of the reactions or rooms occur (He et al., 1994; Lantz et al., 2000; Wright and Wynford-Thomas, 1990). Moreover, biological sample preparation strategies are needed to remove non-specific inhibitors. Multiplexing the PCR for the detection of multiple pathogens or targets is currently employed to enable the testing of samples for multiple pathogens in a single run. Several multiplex or simultaneous PCR systems for the detection of food-borne and other infectious pathogens are also being developed (Fukushima et al., 2010; Jothikumar and Griffiths, 2002; Skottman et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2005). Despite the advantages, when multiplexing PCR, optimal reaction conditions for the multiple sets of primers have to be identified for all the potential targets to be detected (Markoulatos et al., 2002; McKillip and Drake, 2004).

Pathogenic bacteria of the genera Escherichia, Shigella, Francisella, Salmonella, Vibrio and Yersinia contain species or strains that are considered biothreat agents that, if intentionally introduced into the food supply system, could result in high morbidities, mortalities and severe economic losses. These bacteria therefore constitute organisms of interest in food defense strategies against potential bioterrorism. Molecular diagnostic techniques for the detection of the individual genera or a combination of some of these agents have been developed by various research groups (Pohanka and Skladal, 2009; Song et al., 2005; Versage et al., 2003). However, the progress towards a rapid, fully multiplexed, sensitive and specific real-time PCR platform for the detection of all the six agents is not yet satisfactory.

In an attempt to establish a molecular detection platform amenable to real-time PCR, we first tested several previously reported PCR-primers for their validity for the detection of a wide range of pathogenic and non-pathogenic, as well as related or-unrelated species or strains. While some of the primers or gene targets reported in the literature were further used for our real-time assays, in silico validation of many of the primers against a wide array of bacterial genomes revealed cross reactivity or amplicon sizes not compatible with simultaneous real-time PCR detection of multiple pathogens. Therefore, we utilized whole-genome data mining, text-mining, in silico target and amplicon analysis, and in vitro validation using DNA sequences from representative bacteria. We have identified very specific molecular targets for reliable identification of the six food biothreat agents, and developed a platform with simultaneous detection capability. Interestingly, many of targets we identified have putative functions or code for hypothetical proteins, digressing from the traditional use of previously known gene targets or known pathogenicity-associated molecular detection tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial species and DNA preparation for PCR

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Laboratory level 2 organisms consisted of Shigella dysentriae, Shigella sonnei, and Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica serovar Saintpaul were grown aerobically at 37°C on tryptic soy agar supplemented with 5 % horse blood and tryptic soy broth, the exceptions to this is Vibrio vulnificus, which was grown at 30°C. One ml of culture was collected by centrifugation at 10,000-× g, and pellet re-suspended in sterile 1XPBS solution. DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol recommended for bacterial DNA extraction (Wizard genomic DNA purification kit, Promega). Genomic DNAs of strains, F. tularensis subspecies novicida KM145 and Y. pestis ZE 94–2122 were obtained from Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (BEI Resources). Genomic DNAs of all organisms listed on Table 1, except for F. tularensis subspecies novicida strain U112 and F. tularensis subspecies tularensis strain Schu S4, were purchased from ATCC collection (Manassas, VA). The genomic DNA of the two Francisella subspecies, F. tularensis subspecies novicida U112 and F. tularensis subspecies tularensis Schu S4 were kindly provided by Dr. Karl Klose, University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) STCEID.

Table 1.

List of organisms used in the validation of specific PCR

| Species/ Strain | CDC category |

Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Genus Escherichia | ||

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 | B | ATCC |

| Escherichia coli 1175 | ATCC | |

| Genus Francisella | ||

| Francisella tularensis ssp. tularensis Schu S4 | A | Dr. Karl Klose (UTSA, STCEID |

| Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida U112 | Dr. Karl Klose (UTSA, STCEID | |

| Francisella tularensis ssp. novicida KM145 | ||

| Francisella tularensis ssp. philomiragia | ATCC | |

| Genus Salmonella | ||

| Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Braenderup ATCC (®BAA-664™) | ATCC | |

| Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2 ATCC® (700720D-5™) | B | ATCC |

| Salmonella enterica serovar typhi Ty2 ATCC (®700931™) | B | ATCC |

| Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Saintpaul 127 ATCC (®9712™) | B | ATCC |

| Genus Shigella | ||

| Shigella dysentriae ATCC (®11456a™) | B | ATCC |

| Shigella sonnei ATCC (®11060™) | B | ATCC |

| Genus Vibrio | ||

| Vibrio cholerae ATCC (®39315™) | B | ATCC |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus EB 101 ATCC (®17802™) | ATCC | |

| Vibrio vulnificus Type strain Bio-group 1 ATCC (®27562™) | ATCC | |

| Genus Yersinia | ||

| Yersinia pestis A1122 BEI (NR-15) | A | |

| Yersinia pestis KIM10+ BEI (NR-642) | A | BEI |

| Yersinia pestis ZE 94–2111 | A | ATCC |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis P62 ATCC (29910) | B | BEI (NR-804) |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis NCTC 10275 ATCC (29833) | B | ATCC |

| Yersinia enterocolitica Billups-1803-68 ATCC (23715) | BEI (NR-204) | |

| Yersinia enterocolitica WA ATCC (27729) | ATCC | |

2.2. Genomic and expressed gene data mining

Completed genome sequence data of all of the select agents, including incomplete genome sequence for S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Saintpaul strain SARA 23 were retrieved from the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/lproks.cgi) microbial genome-sequencing database. Most recently published references of comparative genomics of every select agent were used in target region selection. A BLAST search was used in the selection of specific amino acid sequences of all the organisms used in this study. Specific primers were designed from genes and coding regions specific to the agent of interest. These primers were then analyzed in silico for specific binding across the genome sequence of similar species. For more stringency assessment we used V-NTI Advanced-11 (Invitrogen, USA) for the design and modification of primers having a 3` end similarity with the closely related species. All available whole genome sequence and partial sequences from prokaryote genome database of the NCBI were used for the in silico validation of the specific primers.

2.3. Comparative genomic analysis

In search for a specific region, a BLAST analysis was performed for all the species containing a coding sequence of > 500 aa. Further COBALT alignment analysis was used to localize more specific regions for species under question. Once the specific amino acid sequence was localized, we used the nucleotide sequence of this sequence for specific primer design.

2.4. Primer design and preliminary analysis

The primers underwent rigorous testing before the experimental validation. This included oligo-dimer, hair-loop formation and successful standardization of all primers to similar melting temperatures, which is one of the requirements for the simultaneous use of these primers. Primers fulfilling the required criteria were further analyzed for possible binding to a different location within the same whole genome sequence using V-NTI motif search analysis.

2.5. In silico PCR

In silico PCR validations were performed using both http://insilico.ehu.es/PCR/ and V-NTI. Only primers giving specific amplifications were selected for further validation using conventional and real time PCR assay. Primers that showed the most specificity to the target molecule were ordered from Integrated DNA technologies (IDT, IA).

2.6. In vitro PCR and analysis

All PCR reactions were set up in an isolated PCR station (AirClean Systems, NC) that was UV-sanitized daily and after each use. Initial conventional PCR was performed to validate the specificity of the primers for respective organisms. DNA from 23 strains representing major biothreat agents and closely related foodborne pathogens were used for the validation (Table 1). Single target PCR was performed in a 25 µl final volume containing 0.2 µM of forward and reverse primers, 12.5 µl of Pwo Master mix containing 1.25 U of Pwo enzyme, 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM dNTPs (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim Germany). The PCR amplification profile for this initial assay consists of 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 15 seconds at 95 °C, 15 seconds at 60 °C, and 15 seconds at 72 °C using Master cycler pro (Eppendorf, Humburg, Germany). Presences of single band were analyzed using gel electrophoresis.

2.7. Real-time PCR

Real time PCR assay was performed using Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies) for final validation & verification. A specific amplification was obtained with all the primers used to amplify the respective organisms. A reaction volume of 20 µl containing 500 nM of forward and reverse primers, 10 µl of 2X Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBER Green master mix, 0.3 µl ROX reference dye, 1 µl of DNA template, nuclease free H2O added to the final volume was used for the real-time PCR. Cycling conditions consisted of one cycle of segment 1, 2 min at 95 °C; followed by 27 cycles of segment 2, 10 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at 60 °C; completed by one melting curve cycle of 1 min at 95 °C, 30 seconds at 65 °C, and 30 seconds at 95°C.

2.8. Sensitivity assay

Sensitivity of the real-time PCR assay was determined by five-fold serial dilution of the DNA samples (initial DNA concentrations were 2.5 ng/µl for E. coli O157:H7 strain EDL933, 2 ng/µl for Francisella tularensis, 2.6 ng/µl for Shigella dysentriae, 3.7 ng/µl for Salmonella typhi, 3 ng/µl Vibrio cholerae and 3.8 ng/µl for Yersina pestis) in nuclease free double distilled H2O from each of the bacterial species. One microliter of each of the DNA dilutions were used in real time PCR assay mixture. The assay was performed as described above.

2.9. Sensitivity assay in food Matrix

Milk (450 µl) was inoculated with 7.5 × 108 CFU of Shigella dysentriae (attenuated strain) culture suspension and diluted serially up to 10−8. After the dilution, bacteria in each aliquot were immediately concentrated by centrifugation at 12,000 RPM (13,400 × g) for 2 min. Whole genomic DNA was extracted from all of the serially diluted tubes according to the PrepMan Ultra Sample Preparation protocol (Applied Biosystems, CA). The DNA was detected using ShD1 primers by real-time PCR. In parallel, bacterial cultures were initiated to determine the CFU of bacteria in those dilutions.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Species, Design of primers and in silico validation

The list of strains of bacterial species included in this study to establish the PCR detections is given in Table 1. DNA from these organisms were either purchased or donated through specific agreements. Initially, we aimed at developing a simultaneous foodborne pathogen detection platform using published primer sequences. Some of the sequences were found to be not highly specific when tested against a wide array of organisms in silico. Others were not suitable for simultaneous or multiplex detection of the pathogens in the current study. Therefore, we designed an entirely new set of primers or modified the existing sequences to develop our detection system. To this end, we used text mining, genomic data mining, sequence analysis and comparison tools. Specific primers Typhi-vipR-ST2-F and R were adapted from the work done by Jin et al. (2008) modified by removing G from the 3'end of the forward primer and CT from the 5'end. The list of primers designed or used in this study is shown in Table 2. During the process of selection, the primers were initially validated for unique site recognition and strength of complementarities by using the genomic DNA of each organism as a template.

Table 2.

Primers used to establish PCR to detect food threat and major foodborne bacterial pathogens. The primers were used for both conventional and real-time PCR methods established in this study. All the primers except those indicated in the footnote below the table, were newly designed.

| Primer Name | Sequence 5`–3` | Bacterial species | Target gene | Gene Accession No. |

Amplicon Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC2-SLT-R-m EC2-SLT-F-m |

CAGACGAAGATGGTCAAAACGCG AGTTTACGATAGACTTTTCGACCC |

Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 | Stx2 | NP_286976 | 201 bp |

| EC1-Rm EC1-Fm |

TCTGGTTGACTCTCTTCATTCACGG TACAGAGAGAATTTCGTCAGGCACTG |

Escherichia coli O157:H7 str EC4115 | Stx2A | YP_002271797 | 256 bp |

| lacY-ecoli-F lacY-ecoli-R |

GCACTTCAAACTGGCTGGTAATA TGCACCTACGATGTTTTTGACC |

Escherichia coli CFT073 | lacY | NP_752393 | 331 bp |

| FT1-F FT1-R |

GAAGGTCTTCTAGAAAATTCTGCTC TTGCTGGTAATTCGTAGATAATATC |

Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis Schu4 | PdpD2 | YP_170620 | 345 bp |

| FT2-mR FT2-mF |

GGAAGCATAGCTATTAGCATATTCTGG TTGTCTAAAGCAAATATTGAGTGGG |

Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis Schu4 | HP | YP_169554 | 234 bp |

| FN2-F-m FN2-R-m |

ATGCAAAAGATAAGGCTAACTCTT GAATCAATATTCGTTAGGTCTTCA |

Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida U112 | PdpD | YP_898955 | 214 bp |

| All F-R-m All F-F-m |

GGAACACCGTARTTGTTAGCTTGG ATTGGTATCTGTGCTCACGTTGATG |

Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica OSU18 | fusA | YP_762892 | 371 bp |

| ShD1-F ShD1-R |

ATGGTGTCGTCGATAATATCGGCC AAGAGCGTATCTGGAGTATTTCACC |

Shigella dysenteriae Sd197 | Z5694-like protein | YP_405526 | 270 bp |

| ShD2-F-m ShD2-R-m |

GTGATGGTTTGTTAGATTCTACCAA ATGCAATTGCCAATAGACAACCA |

Shigella dysenteriae Sd197 | HP | YP_402814 | 231 bp |

| rhsA-y-Sonnei-F rhsA-y-Sonnei-R |

TATTGCTGCGGTCATACACTGCC CTGATCGAACTTCGATGCCAATCC |

Shigella sonnei Ss046 | rhsA | YP_309648 | 303 bp |

| ipaH-F ipaH-R |

CACAGTGCCTCTGCGGAGCTTCG GAGAGTTCTGACTTTATCCCG |

Shigella sonnei Ss046 | ipaH | YP_310220 | 234 bp |

| Inv-F Inv-R |

TCAAGAATAGAGCGAATTTCATCC TGCTTTTTATCGATTCCATGACCC |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | invC | NP_461815 | 235 bp |

| ST1-F-m-2 ST1-R-m2 |

ATGACCTTTGCAGCTATCGAGTAA AACGAGAGGACGTAATCGCGAA |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi Ty2 | cI phage immunity repressor protein | NP_808111 | 319 bp |

|

†Typhi-vipR-ST2-F †Typhi-vipR-ST2-R |

GGTTTCATCATTTCTGGCCTCC CTGCTCCGTCAAGATCTTTTCACC |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi Ty2 | tviA VI | NP_807946 | 335 bp |

| STM1-F-M STM1-R-M |

CAGATTCATCCATCAAAAAAATGGG GCTAATGCGGCTCTGAACCTGTG |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | IMP | NP_463357 | 229 bp |

| STM2-R-M STM2-F-M |

GACATTCTACGTAACCAGCTTGCT TGAGCGTTCACCCATGGCTAACTGTT |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 | DNA repair ATPase | NP_463355 | 189 bp |

| SS2-F-n SS2-R-n |

GGGAGTGGTTAAAGCAACCGTGTCA TCACAGACTCTTCGGTCCATTCCTT |

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Saintpaul SARA23 | RloF | ZP_03165416 | 312 bp |

| VC1-pho-F VC1-pho-R |

AAGGTTTATCAGTATTAGTCGTGTG TTGCTGGACTGGGTTGACCATAGGG |

Vibrio cholerae M66-2 chromosome I | phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase | YP_002809642 | 212 bp |

| VC2-B-tox-R VC2-B-tox-F |

CCTCAGGGTATCCTTCATCCTTTC CTTCAGCATATGCACATGGAACACC |

Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor str. N16961 | Enterotoxin subunit B | NP_231099 | 239 bp |

| VpH1-F VpH1-R |

GGCGTCGTCTTCTAAATACTGTTC ATGAAACACCATGCACAAACTTCT |

Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633 | thermostable hemolysin delta-VPH | NP_798108 | 249 bp |

| VpH2-F VpH2-R |

CTTTTTAAGAGCGGCAGATATCA ATGACTGCGACTAACTTATTCGTC |

Vibrio parahaemolyticus RIMD 2210633 | thrA | NP_796873 | 105 bp |

| All-Vibrio-rpoBF All-Vibrio-rpoBR |

TGGACATTCCATACCTGCTATCG ACCACGGATTTGACATTCTTTA |

Vibrio vulnificus YJ016 | rpoB | NP_935952 | 203 bp |

| YP1-F-m2 YP1-R-m2 |

CCAGCTATTATAGCAAATAGTAAGGG CAGTGTTTGCATTTAATGGCTT |

Yersinia pestis strain CO92 | Putative phage-related membrane protein | YPO2127 | 206 bp |

| YP2-R-M3 YP2-F-M2 |

ATTGCCGTTCGGGTCTTTCC GGCAATCAACAATACAGCCGTT |

Yersinia pestis strain CO92 | HP | YP_002347092 | 241 bp |

| YPs1-F-M YPs1-R |

AGCAATGTGTCTGAACTTTCTTCA CATATTGCCGTCACCGACTACACC |

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP 32953 | HP | YP_070722 | 348 bp |

| YPs2-R YPs2-F |

CAGGCAACGCTGAGTATTAGGT CTGCTGATGTTGCCATTAGTATGG |

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP 32953 | HP | YP_070711 | 288 bp |

| wzzR wzzF |

TCATCTAAAGCACCAACGAAYACC TATTTGTTGCTCGCAAAGTTGCC |

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP 32953 | rfe | YP_068715 | 211 bp |

These primers were slightly modified by removing G from the 3'end of the forward primer and CT from the 5'end from published sequences (Jin et al. 2008)

RloF= putative protein of unknown function

IMP: Inner membrane protein

HP: Hypothetical protein

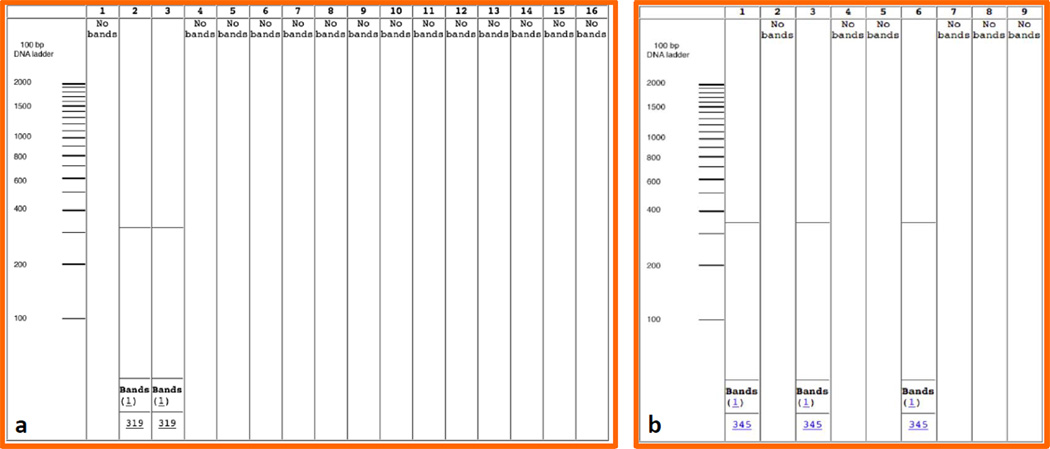

After the primers were designed, we tested the specificity of the primers by performing virtual (in silico) PCR using the publicly accessible tool at http://insilico.ehu.es/PCR/. Examples of pre-validation in silico PCR are shown in Fig. 1. Additionally, we further tested the strength of complementarities and the uniqueness of the binding sites for each primer using the Vector NTI software package (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reference genomic DNA sequences of each of the organisms to be detected were uploaded to the program and the designed primers were run along the entire genomic sequence. Validated primers with 100% complementary binding at a unique site were selected for each organism. These primers were in turn tested for cross reactivity with other genomic DNA sequences, especially against those phylogenetically closely related bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Specific in silico validation performed using our primers 1a. Pre-validation of ST1-F-m-2/R-m-2 primers for S. enterica ssp. enterica s. Typhi 1. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Typhimurium LT2, 2. S. enterica ssp. enterica s. Typhi, 3. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Typhi Ty2, 4. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Paratyphi A str. ATCC 9150, 5. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Choleraesuis str. SC-B67, 6. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Paratyphi B str. SPB7, 7. S. enterica subsp. arizonae s. 62:z4, z23:--8. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Newport str. SL254, 9. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Heidelberg str. SL476, 10. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Schwarzengrund str. CVM19633, 11. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Agona str. SL483, 12. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Paratyphi A str. AKU_12601, 13. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Dublin str. CT_02021853, 14. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Gallinarum str. 287/91, 15. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Enteritidis str. P125109, 16. S. enterica subsp. enterica s. Paratyphi C strain RKS4594; 1b. Pre-validation of FT1-F/R, primers for F. tularensis ssp. tularensis, 1- Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis Schu4, 2 - Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica, 3 - Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis FSC 198, 4 - Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica OSU18, 5 - Francisella tularensis subsp. novicida U112, 6 - Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis WY96-3418, 7 - Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica FTNF002-00, 8 - Francisella philomiragia subsp. philomiragia ATCC 25017, 9 - Francisella tularensis subsp. mediasiatica FSC147

3.2. Conventional PCR and gel electrophoresis analysis for the specificity of the primers

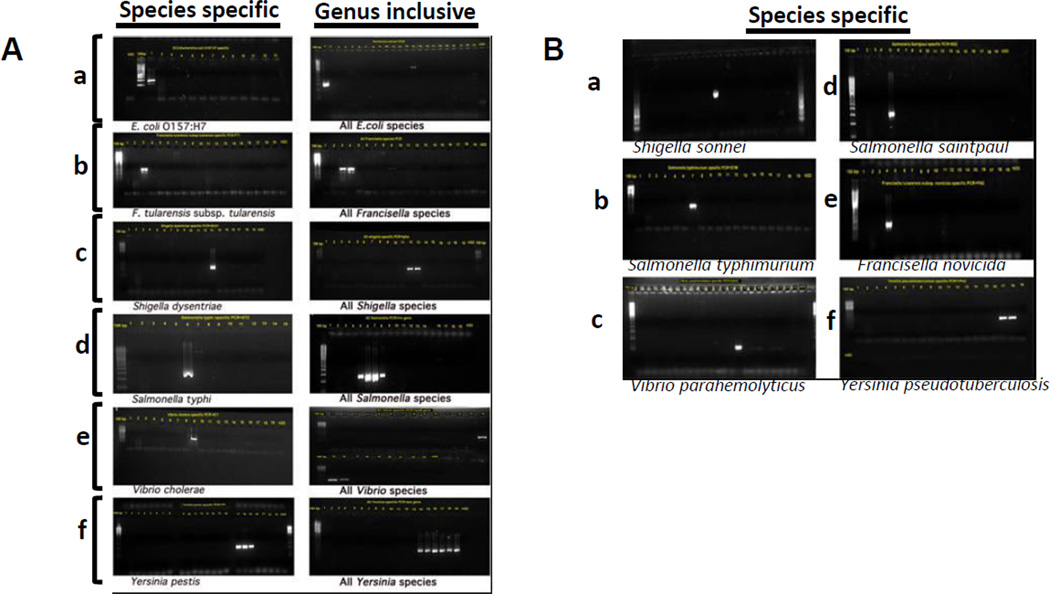

Following in silico analysis and validation, we tested the primers using DNA isolated from strains of species of the foodborne pathogens. Each PCR experiment was designed so that the primers are tested against their template DNA and DNA from the maximum number of closely related species. In parallel, genus inclusive primers were designed and PCR was performed to verify that the target species as well as other members of the genus could be detected. Genus inclusive primers gave an additional quality control to minimize cross reactivity with other genera or species within the genus. PCR products were resolved on 1.5 % agarose gels; the gels were stained with GelRed (Biotium, Hayward, CA) and photographed using AlphaImager (Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA). As shown in Fig. 2, our species-specific primers gave very specific detection that discriminated each of the target species, whereas the genus-inclusive primers distinctively identified other members of the genus simultaneously with the target. Therefore, these conventional PCR data provided strong evidence that the primers were very specific, and yielded products of the expected size under the experimental conditions employed. Only a minor cross reactivity of the Escherichia genus specific primers with Vibrio cholera was noticed in this assay. However, the size of the product was larger than expected and also the intensity of the band was weak.

Fig. 2.

(A and B). Validation of the specificity of the primers by conventional PCR and gel electrophoresis to detect biothreat agents (A) and major foodborne pathogens (B): A. a. detection of E. coli O157:H7 using the EC2 primers and a genus inclusive primer (right panel) b. detection Francisella using F. tularensis ssp tularensis (FT2, left panel) and genus inclusive primers (F. tularensis and F. novicida shown in the right panel); c. detection of Shigella using S. dysentriae primers (ShD1, left panel) and genus inclusive (S. dysentriae and S. sonnei shown in the right panel) primers d. detection of Salmonella using the ST2 primers for Salmonella typhimurium (left panel) and genus-inclusive primers (S. typhi, S. typhimurium, S. saintpaul, and S. braenderup shown in the right panel); e. detection of V. cholerae using VC1 primers (left panel) and Vibrio genus inclusive primers (V. cholerae, V. parahemolyticus, and V. vulnificus (right panel); f. detection of Yersinia using YP1 primers for Y. pestis (left panel) or genus inclusive primers (three different Y. pestis strains, two Y. pseudotuberculosis strains, and Y. enterocolitica (right panel)). B. Validation of specificity of primers to major foodborne pathogens: a. detection of Shigella sonnei using rhs-y-Sonnei-F/R, b. detection of Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica serovar Typhimurium using STM-F-M/R-M, c. detection of Vibrio parahemolyticus using VpH1-F/R, d. Salmonella enterica ssp. enterica serovar Saintpaul using SS2-F-n/R-n; e. Francisella tularensis ssp novicida using FN2-F-m/R-m; and f. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis using YPs1-F-M/R.

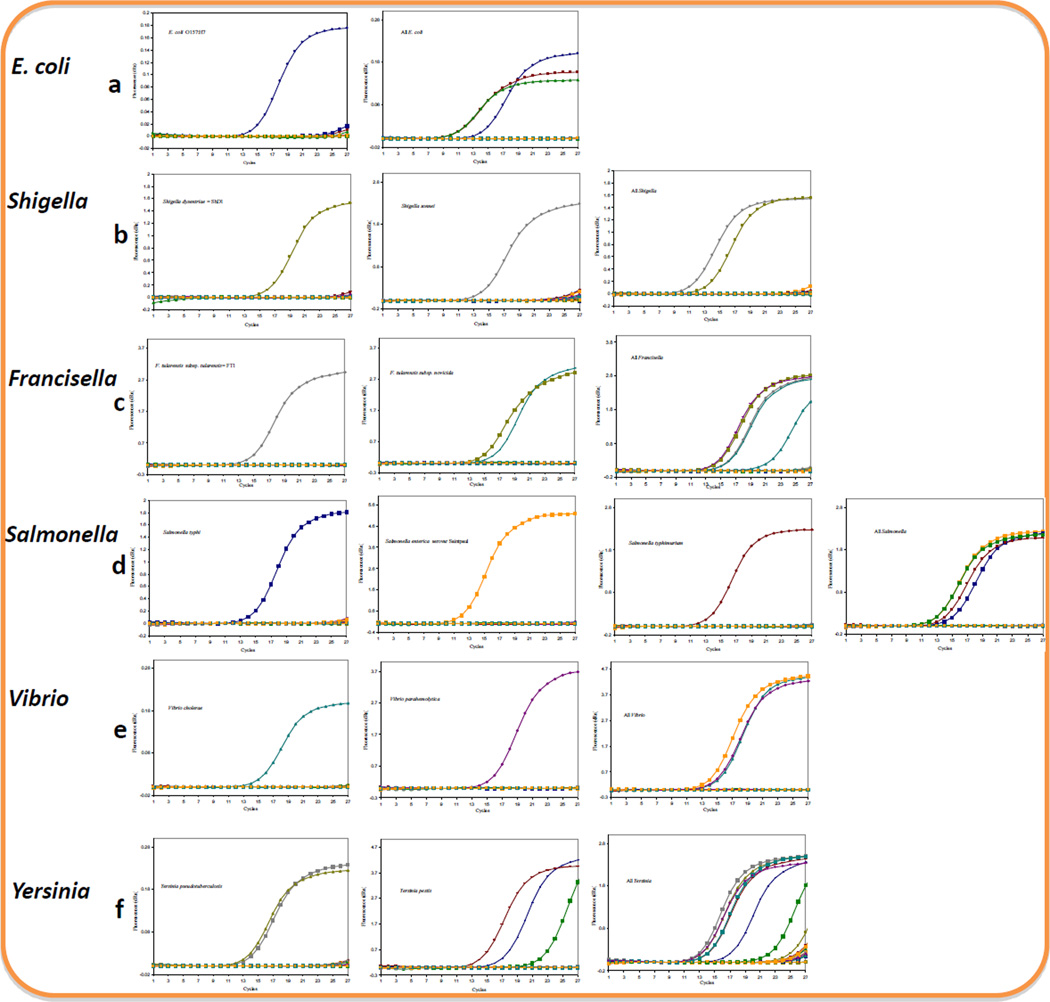

3.3. Validation of the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens DNA by real-time PCR

The conventional PCR method was employed as described above to visualize the PCR products and determine the specificity of our detection. However, as conventional PCR is time consuming and labor intensive, it is not practical to use it for the detection of pathogens in a high throughput platform. Therefore, we wanted to determine the suitability of our primers and the PCR system in a real-time setup. PCR conditions were selected so that a species-specific primer was used to detect DNA from target and other bacteria arrayed on 96-well plates. The average amount of DNA concentration used per well was 2 ng/µl. On the array, one well was designated for DNA from one bacterial species or strain. While DNA was added to the designated wells, a primer solution was aliquoted to all the 23 wells on the array corresponding the different species listed on Table 1. A positive curve was expected to be generated only from the wells containing primers and the target DNA in the same well. In a parallel array of 23 wells, genus-inclusive primers were also aliquoted to all the wells containing DNA from the target species as well as other bacteria, including members of the genus. Positive curves were anticipated only from wells designated to the members of the same genus. As shown in Fig. 3, single curves were generated with all of the primers we tested. Since we did not multiplex the PCR, the multiple curves shown in Fig. 3 were generated by merging data from the corresponding single curves originating from parallel simultaneous detection of different strains of the same species.

Fig. 3.

Validation of the specificity of the primers against DNA from 23 foodborne pathogens and related bacterial species (listed in table 2) by real-time PCR: Detected were a. E. coli (left panel 0157:H7, right panel 0157:H7, HB101, and ATCC 1175 strains with genus-inclusive primers) b. Shigella (left panel S. dysentriae, middle panel S. sonnei, right panel S. dysentriae and S. sonnei with genus inclusive primers) c. Francisella (right panel F. tularensis ssp tularensis, middle panel two strains of F. tularensis ssp. novicida, and right panel all Francisella with genus inclusive primers) d. Salmonella (panels from left to right: 1st S. typhi, 2nd S. enterica ssp enterica s. Saintpaul, 3rd S. enterica ssp enterica s. Typhimurium, 4th all Salmonella with genus inclusive primers, e. Vibrio (left panel V. cholerae, middle panel V. parahemolyticus, right panel all Vibrios with genus inclusive primers f. Yersinia (left panel Y. pseudotuberculosis, middle panel Y. pestis, and right panel all Yersinia with genus inclusive primers). PCRs using genus inclusive primers and those on multiple strains of the same species e.g. Y. pestis (f) were run separately, and the amplification plots were merged. The highest number of cycles used for all the plots is 27.

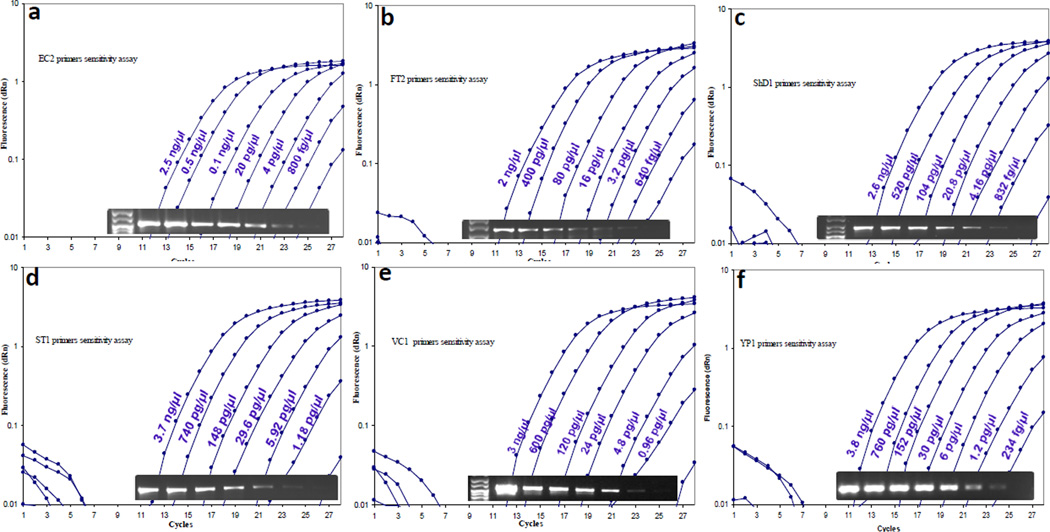

3.4. Evaluation of the sensitivity of real-time PCR for the detection of DNA from foodborne pathogens

To evaluate the sensitivity of our real-time assay, we serially diluted 1:5 the DNA from each of the major pathogen and performed real-time PCR detection on each of the dilutions. One microliters of each of the dilution was used in a 20 µl total PCR reaction volume and the PCR was run for 27 amplification cycles. At the end of the run, 4 µl aliquots from each of the wells were resolved on a 2 % agarose gel and visualized by GelRed staining (Biotium®). As shown in Fig. 4, the sensitivity of the assay was variable between the organisms used; e.g., starting with 3.8 µg/µl DNA, a 230 fg/µl dilution was detectable for Y. pestis DNA while 640 fg/µl of diluted F. tularensis DNA was reliably detected for both species at threshold cycles below 27. The overall detection range varied between 234 fg/µl (Y. pestis) and 1.18 pg/µl (S. typhimurium). The gel electrophoregrams also showed generation of bands of the correct size as well as visible limits of the serial dilution under conditions of the experiment. Therefore, under these conditions, we were able to achieve a high sensitivity of detection combined with the high specificity described above.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of the real-time PCR assay to detect six major foodborne pathogens: Aliquots of DNA from E. coli O157:H7 (a), S. dysentriae (b), F. tularensis ssp. tularensis (c), S. enterica ssp enterica s. Typhi (d), V. cholerae (e), and Y. pestis (f), were serially five-fold diluted and analyzed by real-time PCR to determine the lowest detection limit of the assay. At the end of the 27 cycles of PCR, aliquots of the reactions were also resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis to examine the PCR products and intensity from each dilution (lower inset panels).

3.5. Evaluation of the application of the real-time PCR detection for bacteria in food matrix

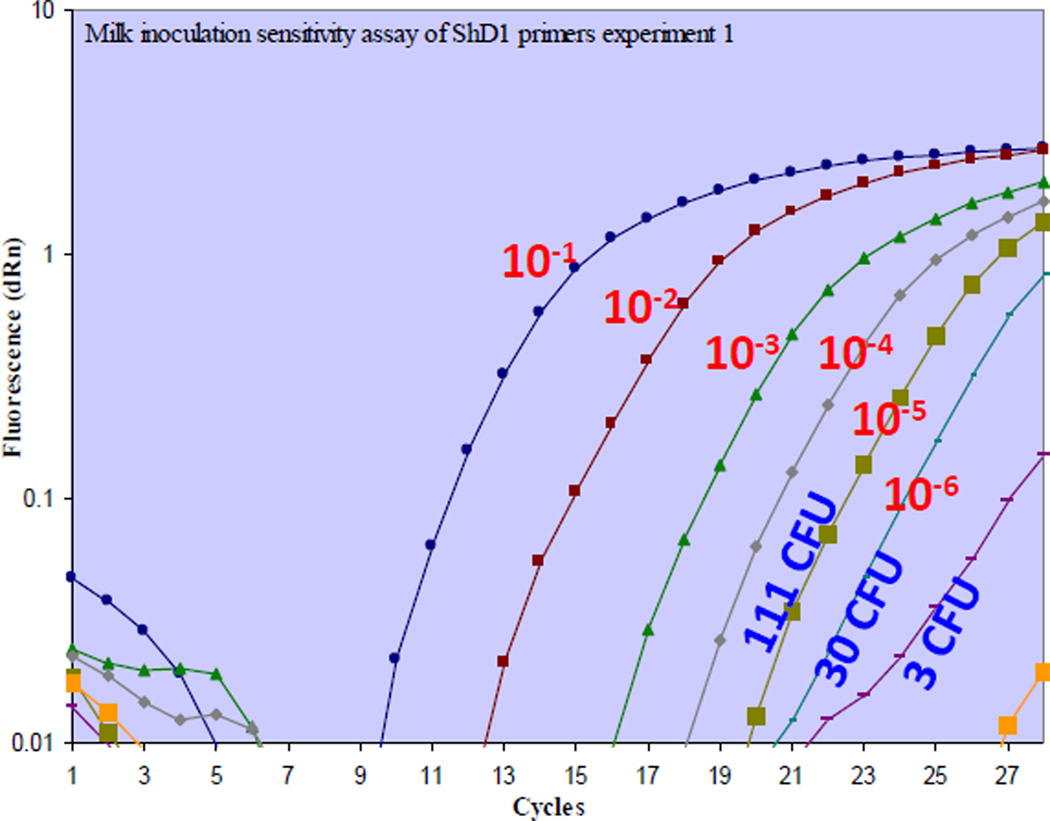

Finally, to preliminarily evaluate if our real-time detection approach would be compatible with DNA isolated from bacteria in a food matrix, we spiked commercially available skimmed milk with 7.5×108 attenuated S. dysentriae bacteria (ATCC) and serially diluted 1:10 the suspension in a total of 500 µl volumes. Immediately after the serial dilution, tubes were centrifuged to concentrate the bacteria and total DNA was isolated as described in materials and methods. Parallel cultures were also initiated from each dilution to count colony-forming units. As shown in Fig. 5, we were able to detect DNA isolated from milk spiked with Shigella organisms with an approximate detection limit of 6–60 colony forming units per ml of milk in less than one hour of experiment time.

Fig. 5.

Sensitive detection of Shigella dysentriae in milk using real-time PCR assay: Attenuated S. dysentriae bacteria (7.5 × 108 CFU) were serially 10-fold diluted in milk as described in materials and methods. Bacteria suspended in each of the 500µl serial dilution volumes were concentrated, and genomic DNA was isolated. The DNA was detected using ShD1 primers by real-time PCR. In parallel, bacterial cultures were initiated to determine the CFU of bacteria in those dilutions. The real time PCR assay was able to detect DNA isolated from at least 3–30 CFU/500µl (6–60 CFU/ml) of S. dysentriae in milk.

4. Discussion

We have developed a PCR-based real-time detection platform for simultaneous, rapid, sensitive and differential molecular detection of six primary biothreat agents, namely, Escherichia, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio, Yersinia and Francisella. Through extensive genomic data mining, text mining and multiple layer validation, we have identified 26 new target sequences (Table 2), which enabled us to design the platform with improved specificity. Some of these targets have a well-known functions such as stx2A (shiga toxin subunit A from E. coli O157:H7), fusA (Elongation factor A from F. tularensis ssp. tularensis), ipaH (invasive plasmid antigen from Shigella species), invC (invasion protein from Salmonella species), rpoB (DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta, from Vibrio species). However, others have hitherto unknown functions such as in RloF gene from S. enterica ssp. enterica s. Saintpaul with putative functions, or hypothetical proteins such as pdpD (pathogenicity determinant protein D from F. tularensis ssp. tularensis). Moreover, we preliminarily evaluated the utility of the platform using milk as a food matrix into which Shigella organisms were spiked.

One of the known challenges in multiplexed or simultaneous PCR-based molecular detections is the need for optimization of the reaction conditions such as annealing temperatures optimal for all primer sets, avoiding primer dimers, generation of compatible amplicon sizes, and adjustment for different amplification efficiencies (Edwards and Gibbs, 1994). In this study, we have identified PCR conditions that are suitable for the amplification of 105 bp to 371 bp fragments from all the six pathogens under the same reaction conditions. Moreover, the specificities of the primers were tested and validated against a broad array of potential biothreat agents and related species or strains, which do not pose threat. For example, the Francisella tularensis ssp tularensis detection primers used in this study, designed from a hypothetical protein gene pdpD2, were tested against four other strains, Francisella subspecies (holartica, novicida, and mediasiatica) and the closely related F. philomiragia ssp philomiragia, and showed reactivity only to the F. tularensis ssp tularensis. On the other hand, F. tularensis ssp novicida primers based on another gene for hypothetical protein pdpD were specific to the subspecies, without detecting any of the other F. tularensis subspecies. Despite the degree of specificity we achieved with these primers, our E. coli O157:H7 primers EC1 and EC2 still in-silico cross detected the non-O157 E. coli such as O111 and O103, strains that evolved parallel to the O157 strain (Ogura et al., 2009). However, since such non-O157 strains also possess pathogenic potential (Reid et al., 2000), the ability of our primers to detect non-O157 strains may be a desirable feature in the investigation of E. coli outbreaks.

Because of their close evolutionary relationship, differentiation of Escherichia from Shigella species poses a big challenge (Jin et al., 2002; Pupo et al., 2000). In our study, even challenging was the distinction among Shigella species, especially Shigella sonnei from other members of the genus. After extensive comparative genome analysis, we identified the gene for rhsA protein in rhs element as target for the specific identification of S. sonnei. Similarly, Salmonella enterica ssp enterica s. typhimurium was identifiable by targets in the genes for putative inner membrane protein and putative DNA repair ATPase. On the other hand, while Vibrio parahemolyticus was identifiable using the hemolysin gene VP1729, Vibrio cholerae was identifiable using the gene for phosphotyrosine protein phosphatase VC0916 as a target.

Our primers based on the genes for putative phage-related membrane protein (YPO2127) and the hypothetical protein YpAngola A2197 were able to detect all Y. pestis strains except the biovar Microtus strain 91001. Lack of identification of this organism using our present assay would not be a major problem since there has been so far no evidence that human plaque can arise from Microtus strains (Zhou et al., 2004). Furthermore subcutaneous inoculation of strains from serovar Microtus has demonstrated no virulence (Song et al., 2004). The genes for YPTS_2284 and YPTB2194 hypothetical proteins were also specific targets for the identification of Y. pseudotuberculosis isolates. These two regions were selected from a set of 67 refined species-specific genes (Mark Eppinger et al., 2007). While the targeting of hypothetical proteins for detection of the bacteria may not directly correlate with the hitherto known pathogenicity or virulence of the organisms, genetic studies may reveal the significance of these gene products in bacterial biology or host interaction, or even pathogenicity. The identification of these genomic regions as specific to the particular species or even sub species is an important step in advancing pathogen detection techniques by providing additional targets.

We were able to verify our in silico results by in vitro differential identifications under identical PCR conditions. In previous studies other groups had also developed multiplexed PCR assays to simultaneously detect multiple food borne pathogens (Fukushima et al., 2010; Jothikumar and Griffiths, 2002; Skottman et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2005). While our approach is similar in some aspects, for the first time we have combined into one assay the detection of primary biothreat agents of bioterrorism potential, and identified highly specific targets capable of discriminating a broad range of pathogens or related bacteria. In this study, we did not multiplex the primers or DNA in a single tube. With added future improvements for even more rapid differential detection and multiplexing capabilities, our assay platform provides a strong foundation to strengthen national and international food defense strategies as a promising component of primary detection or confirmatory platforms.

Through this study, we also have designed highly specific primers that yielded PCR assays with high sensitivity and low detection limits. For example to the detection limit for F. tularensis in this study are comparable to or better than some other reports (Sellek et al., 2008; Svensson et al., 2009), although different sources of DNA and procedures of detection may influence the detection limits.

Food matrices provide a critical challenge in amplification-based pathogen detection approaches. Improved pre-analytical sample processing techniques are needed to reduce the time needed to arrive at diagnosis and decision-making (Benoit and Donahue, 2003; Dwivedi and Jaykus, 2011). Previous studies have shown immunomagnetic separation method to provide better concentration of bacteria from food matrices such as chicken meat (Taha et al., 2010). In milk, a combination of the two techniques, i.e. immunomagnetic separation and polymerase chain reaction, provided a detection of 1–10 CFU of salmonellae/ml, after a selective pre-enrichment incubation of 12–16 hrs. However, a decreased sensitivity of 10–100 CFU/ml was observed after 8–10 h of pre-enrichment period (Mercanoglu Taban et al., 2009). In this study we have performed a preliminary test to evaluate the use of real-time PCR for detection of S. dysentriae spiked in milk. Using centrifugation to concentrate the bacteria serially diluted in milk, we were able to detect about 6–60 CFU/ml of milk matrix, without an enrichment step. According to CDC, 10–100 organisms of S. dysentriae are considered the minimum infectious dose with possible secondary transmission (Sobel et al., 2002).

Caution is needed in correlating the CFU findings with PCR detection limits, because in general, PCR does not discriminate between live and dead organisms. Therefore, any correlation between our DNA detection limit and the observed CFU per dilution may not be direct. For example, if there is a time lapse between sample collection and PCR analysis, the CFU could underestimate the degree of contamination of the food matrix. Alternatively, sterilized products containing non-viable bacteria or their DNA may still yield positive data. Although our studies using food matrix are still preliminary, we were able to detect organisms in a milk matrix with reasonable sensitivity. Further work is needed to improve recovery of pathogen DNA from such matrices and improve the sensitivity. Ultimately the findings of this study will contribute to an effective means of identifying high impact pathogenic agents in human food supply systems before the agents reach the consumer.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through NCFPD grant to WA (Award Number 2007-ST-061-000003). We thank Dr Karl Klose, who provided us the Francisella DNA, and BEI Resources for Francisella and Yersinia DNA. Research in TS lab is supported by NIH grant SC2138178. In part this research was supported by the Center for Biomedical Research Grant # 5G12RR003059-22 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a part of the NIH, and the CVMNA endowment fund NIH Grant # 2 S21 MD 000102. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

References

- Benoit PW, Donahue DW. Methods for rapid separation and concentration of bacteria in food that bypass time-consuming cultural enrichment. J Food Prot. 2003;66:1935–1948. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-66.10.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busta FF, Shaun PK. Defending the safety of the global food system from intentional contamination in a changing market. In: Hefnawy M, editor. Advances in Food Protection [Focus on Food Safety and Food Defense. (Security and Safety against Terrorist Threats and Natural Disasters) NATO/SPS Advanced Research Workshop Proceedings] NATO Science for Peace and Security Series A: Chemistry and Biology. New York: Springer Publishing; 2011. pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi HP, Jaykus LA. Detection of pathogens in foods: the current state-of-the-art and future directions. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:40–63. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2010.506430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MC, Gibbs RA. Multiplex PCR: advantages, development, and applications. PCR Methods Appl. 1994;3:S65–S75. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.4.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima H, Kawase J, Etoh Y, Sugama K, Yashiro S, Iida N, Yamaguchi K. Simultaneous Screening of 24 Target Genes of Foodborne Pathogens in 35 Foodborne Outbreaks Using Multiplex Real-Time SYBR Green PCR Analysis. Int J Microbiol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/864817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Marjamaki M, Soini H, Mertsola J, Viljanen MK. Primers are decisive for sensitivity of PCR. Biotechniques. 1994;17:82–84. 86–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Yuan Z, Xu J, Wang Y, Shen Y, Lu W, Wang J, Liu H, Yang J, Yang F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Yang G, Wu H, Qu D, Dong J, Sun L, Xue Y, Zhao A, Gao Y, Zhu J, Kan B, Ding K, Chen S, Cheng H, Yao Z, He B, Chen R, Ma D, Qiang B, Wen Y, Hou Y, Yu J. Genome sequence of Shigella flexneri 2a: insights into pathogenicity through comparison with genomes of Escherichia coli K12 and O157. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4432–4441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jothikumar N, Griffiths MW. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 with multiplex real-time PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3169–3171. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.6.3169-3171.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S. Epidemiology. Why can't we test our way to absolute food safety? Science. 2008;322:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.1163867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PG, Abu al-Soud W, Knutsson R, Hahn-Hagerdal B, Radstrom P. Biotechnical use of polymerase chain reaction for microbiological analysis of biological samples. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2000;5:87–130. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(00)05033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Eppinger MJ, Rosovitz, Fricke WF, Rasko DA, Kokorina G, Fayolle C, Lindler LE, Carniel E, Ravel J. The Complete Genome Sequence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP31758, the causative agent of Far East Scarlet-Like Fever. PLoS Genetics. 2007;3:1508–1523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulatos P, Siafakas N, Moncany M. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction: a practical approach. J Clin Lab Anal. 2002;16:47–51. doi: 10.1002/jcla.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillip JL, Drake M. Real-time nucleic acid-based detection methods for pathogenic bacteria in food. J Food Prot. 2004;67:823–832. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercanoglu Taban B, Ben U, Aytac SA. Rapid detection of Salmonella in milk by combined immunomagnetic separation-polymerase chain reaction assay. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2382–2388. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Ooka T, Iguchi A, Toh H, Asadulghani M, Oshima K, Kodama T, Abe H, Nakayama K, Kurokawa K, Tobe T, Hattori M, Hayashi T. Comparative genomics reveal the mechanism of the parallel evolution of O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17939–17944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903585106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohanka M, Skladal P. Bacillus anthracis, Francisella tularensis and Yersinia pestis. The most important bacterial warfare agents - review. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2009;54:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s12223-009-0046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupo GM, Lan R, Reeves PR. Multiple independent origins of Shigella clones of Escherichia coli and convergent evolution of many of their characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10567–10572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180094797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SD, Herbelin CJ, Bumbaugh AC, Selander RK, Whittam TS. Parallel evolution of virulence in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;406:64–67. doi: 10.1038/35017546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellek R, Jimenez O, Aizpurua C, Fernandez-Frutos B, De Leon P, Camacho M, Fernandez-Moreira D, Ybarra C, Carlos Cabria J. Recovery of Francisella tularensis from soil samples by filtration and detection by real-time PCR and cELISA. J Environ Monit. 2008;10:362–369. doi: 10.1039/b716608g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skottman T, Piiparinen H, Hyytiainen H, Myllys V, Skurnik M, Nikkari S. Simultaneous real-time PCR detection of Bacillus anthracis, Francisella tularensis and Yersinia pestis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:207–211. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0262-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J, Khan AS, Swerdlow DL. Threat of a biological terrorist attack on the US food supply: the CDC perspective. Lancet. 2002;359:874–880. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07947-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Ahn S, Walt DR. Detecting biological warfare agents. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1629–1632. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Tong Z, Wang J, Wang L, Guo Z, Han Y, Zhang J, Pei D, Zhou D, Qin H, Pang X, Zhai J, Li M, Cui B, Qi Z, Jin L, Dai R, Chen F, Li S, Ye C, Du Z, Lin W, Yu J, Yang H, Huang P, Yang R. Complete genome sequence of Yersinia pestis strain 91001, an isolate avirulent to humans. DNA Res. 2004;11:179–197. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Back E, Eliasson H, Berglund L, Granberg M, Karlsson L, Larsson P, Forsman M, Johansson A. Landscape epidemiology of tularemia outbreaks in Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1937–1947. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.090487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taha EG, Mohammed A, Srivastava KK, Reddy PG. Rapid Detection of Salmonella in chicken meat using Immunomagnetic separation, CHROMagar, ELISA and Real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) International Journal of Poultry Science. 2010;9:831–835. [Google Scholar]

- Versage JL, Severin DD, Chu MC, Petersen JM. Development of a multitarget real-time TaqMan PCR assay for enhanced detection of Francisella tularensis in complex specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5492–5499. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5492-5499.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ, Erler AM, Nasarabadi SL, Skowronski EW, Imbro PM. A multiplexed PCR-coupled liquid bead array for the simultaneous detection of four biothreat agents. Mol Cell Probes. 2005;19:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PA, Wynford-Thomas D. The polymerase chain reaction: miracle or mirage? A critical review of its uses and limitations in diagnosis and research. J Pathol. 1990;162:99–117. doi: 10.1002/path.1711620203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Tong Z, Song Y, Han Y, Pei D, Pang X, Zhai J, Li M, Cui B, Qi Z, Jin L, Dai R, Du Z, Wang J, Guo Z, Huang P, Yang R. Genetics of metabolic variations between Yersinia pestis biovars and the proposal of a new biovar, microtus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5147–5152. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.5147-5152.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]