Abstract

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is a hereditary cancer syndrome where affected individuals are predisposed to the development of multiple leiomyomas of the skin and uterus and aggressive forms of kidney cancer. Affected individuals harbor a germline heterozygous loss-of-function mutation of fumarate hydratase (FH) gene. Uterine leiomyomas are present in up to 77 percent of women with this syndrome. Previous studies have shown that inactivation of the FH gene is unusual for non-syndromic leiomyomas. Therefore, it might be possible to distinguish two genetic groups of smooth muscle tumors: the most common group of sporadic uterine leiomyomas without FH gene inactivation and the more unusual group of HLRCC leiomyomas in patients that harbor a germline mutation of FH, although the exact prevalence of hereditary HLRCC is unknown. We reviewed the clinical, morphological and genotypical features of uterine leiomyomas in 19 HLRCC patients with FH germline mutations. Patients with HLRCC syndrome were younger in age compared with regular leiomyomata. DNA was extracted by microdissection and analysis of LOH at 1q43 was performed. Uterine leiomyomas in HLRCC have young age onset and are multiple with size ranging from 1 to 8 cm. Histopathologically, HLRCC leiomyomas frequently had increased cellularity, multinucleated cells and atypia. All cases showed tumor nuclei with large orangiophillic, nucleoi surrounded by a perinucleolar halo similar to the changes found in HLRCC renal cell cancer. Occasional mitoses were found in three cases; however the tumors did not fulfill the criteria for malignancy. Our study also showed that LOH at 1q43 was frequent in HLRCC leiomyomas (8/10 cases), similarly to what it has been previously found in renal cell carcinomas from HLRCC patients. LOH is considered to be the second hit that inactivates the FH gene. We conclude that uterine leiomyomas associated with HLRCC syndrome have characteristic morphologic features. Both, uterine leiomyomas and renal cell carcinoma share some morphological nuclear changes and genotypical features in HLRCC patients. The specific morphological features of the uterine leiomyomas that we describe, may help to identify patients that may be part of the hereditary syndrome.

Keywords: Familiar renal cancer syndrome, Fumarate hydratase mutation, HLRCC, Uterine Leiomyoma

Introduction

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is a hereditary cancer syndrome in which affected individuals are predisposed to the development of leiomyomas of the skin and uterus. 10 in addition, affected individuals are also at risk for the development of an aggressive form of kidney cancer. 10 Of 13 individuals identified with kidney cancer in the first reported cohort of North American families, nine patients succumbed to metastatic disease within 5 years from initial diagnosis.21 Affected individuals harbor a germline heterozygous loss-of-function mutation of fumarate hydratase (FH) gene. 10,22,25 HLRCC is also known as multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis syndrome. The exact prevalence of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is unknown. Kidney cancers are less penetrant than leiomyomatous manifestations in HLRCC-affected families.25 Cutaneous leiomyomas were first identified in 1854.24 The association between cutaneous and uterine leiomyomas has been known for many years as Reed syndrome.18 Leiomyomatosis is a condition defined by the occurrence of multiple leiomyomas throughout the body, with often poorly defined nodules that invade areas of the skin on the arms, chest, legs, and in extremely rare cases, the uterus. Renal tumors have been identified in approximately one-third of HLRCC families. To consider the possibility of HLRCC or screening for renal cell cancer in leiomyomatosis is an important issue that needs to be addressed. There is conflicting evidence about the frequency of germline FH mutations in patients with cutaneous leiomyomas (ranging from none to 80%). Uterine leiomyomas are present in up to 77 percent of women. In this report we describe specific morphological changes in the uterine leiomyomas of HLRCC patients that may provide additional helpful information to identify patients that may be part of the HLRCC familiar syndrome.

Material and methods

Nineteen female members of families with known HLRCC syndrome and with multiple uterine leiomyomas were studied. All patients had been evaluated at the Urologic Oncology Branch of the NCI under an approved protocol by the NCI-Institutional Review Board. Appropriate informed consents were obtained. Patients were interviewed for history of cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas, hysterectomy, and renal tumors. Uterine leiomyomas were documented by history, review of medical records, physical examination, MRI, CT, and/or ultrasonography. All H&E slides (with a minimum of three) from all cutaneous, renal and uterine lesions were obtained for review.

Morphological definitions

We followed the WHO standard histopathological criteria for the diagnosis of smooth muscle tumors,4 and is summarized as follows: Histologically, the leiomyomas showed well circumscribed nodular arrangements of interlacing bundles of smooth muscle fibers with a large centrally located blunt-edged nucleus. There was no evidence of atypia or coagulative necrosis and less than or equal to 5 mitoses per 10 high power fields (HPF). Cellular leiomyomas showed increased cellularity without significant nuclear pleomorphism with no evidence of coagulative tumour cell necrosis and less than 5 mitoses per 10 HPF. Atypical leiomyomas (AL) had increased cellularity and marked cellular pleomorphism with occasional mitotic figures (less than 10 per 10HPF, the WHO criteria for malignancy for spindle-cell-appearing smooth muscle tumor). No evidence of coagulative tumour cell necrosis or abnormal mitosis was found.

Sequencing of the fumarate hydratase gene

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes according to standard procedures. The genomic sequence containing FH was determined by BLAST alignment of the mitochondrial FH precursor cDNA (Acc. No. NM_000143) with the assembled genomic sequence (NCBI build 34). Methods for identification of exon/intron boundaries and high throughput DNA sequencing were as previously described.

LOH analysis

DNA extraction from microdissected samples

Manually microdissected normal and procured tumor cells were resuspended in a solution containing 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K, and incubated 48 hours at 55 ° C. The mixture was boiled for 10 minutes to inactivate proteinase K. 1.5-ul of this mixture was used as a template in each PCR-based microsatellite analysis.

PCR Analysis

Matched tumor and normal cells from the same patient were subjected to PCR analysis. Fluorescent labeled primers were obtained from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL). Oligonucleotide primers flanking microsatellite polymorphisms at D1S517S1S2785AFM214D1S547D1S2482 were used in the study. The markers were located 2.2, 0.8, and 0.2 Mb to the left, AFM214 within the gene, and 0.1 and 2 Mb to the right of FH gene on chromosome 1, respectively. The fluorescently labeled PCR primers used to amplify microsatellite loci were purchased from Applied Biosystems (ABI; Foster City, CA). The PCR reaction was performed using ABI Prism True Allele PCR Premix. Each 10-ul reaction consisted of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5uM of each primer and 0.2 units of Taq polymerase from PE. Amplification was done at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min. Water blanks were included in each PCR. LOH analysis: 1 ul of labeled amplified DNA was mixed with 12.5 ul of formamide and 0.5 ul of Ganescan 500 TAMRA. The samples were denatured for 5 min at 94 °C and then analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on the PE Applied Biosystems 310 Genetic Analyzer with Genescan 2.1 software. The Genotyper labels the alleles of the normal lymphocytes or inflammatory cells and the corresponding peaks in bronchial cells and tumor tissue. All DNA templates were coded such that investigators were unaware of the pathological data from patients until the analysis was complete. Only primers that demonstrated heterozygosity in normal cell DNA were considered informative. Non informative cases included those with homozygous alleles in normal tissue and cases in which allelic patterns could not be clearly distinguished by the capillary electrophoretic methods used.

Allelic loss (LOH) was calculated by comparison of the allele ratio of normal cells with the allele ratio in fibroid and tumor cells. The criterion for LOH was at least a 40% reduction of the lesional allele with the subsequent modification of the allele ratio (Fig. 2). To assess the reproductability of the LOH patterns we microdissected different areas from the same tumor section. A consistent pattern was observed in all cases when studies were repeated (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Example of LOH in different lesions from the same patient. D1S2785 and D1S517 Microsatellite markers demonstated allelic loss (red arrows) in both atypical leiomyoma and cellular leiomyoma from patient #2.

The comparison of the allele ratio between lesional and normal DNA demonstrated a similar increase with both markers: From 1.9 in normal to 3.2 in the cellular leiomyoma and 5.5 in the atypical leiomyoma for D1S2785; from 1.6 in normal to 3.3 in the cellular and 4.8 in the atypical leiomyomas for D1S517.

Results

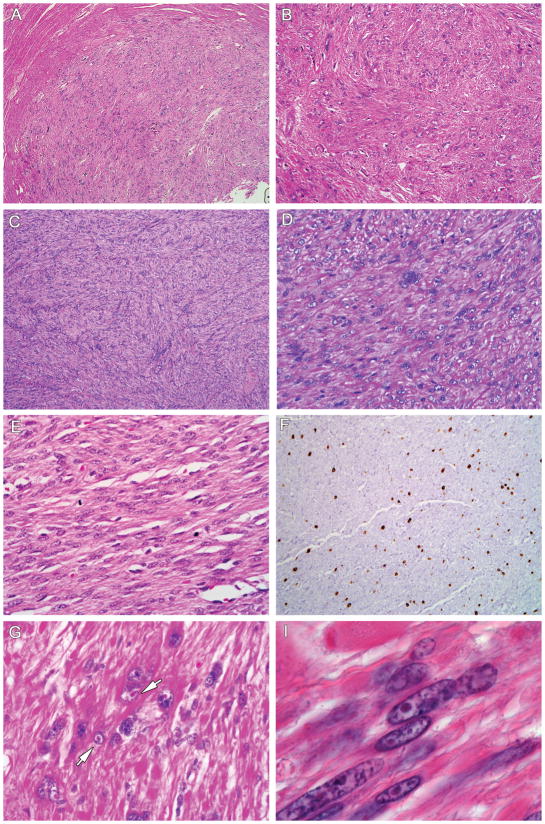

Table 1 summarizes the results of our study. Patients ranged in age from 24 to 47 median 32 year-old). The leiomyomas were histopathologically diagnosed as cellular leiomyomas (6 cases) and atypical leiomyomas (13 cases). Nine patients had a previous history of cutaneous leiomyomas and five had a previous history of renal cancer. Leiomyomas were multiple in all patients, with maximum size ranging from 1 to 8.5 cm. Histopathologically, HLRCC uterine leiomyomas were well circumscribed, fascicular tumors that frequently had increased cellularity and nuclear atypia. The most characteristic change was the presence in every case of occasional cells that had large multinucleated or single nuclei showing orangiophilic prominent nucleoli surrounded by a perinucleolar halo (Fig. 1A). These inclusion-like nucleoli are seen in renal cancer cells (Fig. 1B) but not in cutaneous leiomyomas from HLRCC patients. This finding can be seen on low power and is variably extensive throughout the tumour with focal distribution. Although occasionally mitoses were found (Table 1), tumors did not fulfill established criteria of malignancy. No evidence of coagulative tumour cell necrosis or atypical mitosis was seen in any of these cases.

Table 1.

Summary of the histopathological and genotypical alterations of uterine leiomyomas in 15 cases of HLRCC patients. #: case number, type of germline mutation, ex: exon where the mutation is located, LOH recorded as yes or no, age of patients when hysterectomy was performed, Hist: Histopathological diagnosis (L: leiomyoma, AL: atypical Leiomyoma, CL: cellular leiomyoma, Multi/Atypia: presence of multinucleated cells was scored as few (+) or more frequent (++) and atypia was scored as mild (+) or marked (++). Mitosis: absent (−) or 1–3 (+), CL: “Yes” when patient has previous history of cutaneous leiomyomas and RC: Scored “Yes” when they had history of renal cancer.

| # | Germline Mutation | Ex | Codon | LOH | age | Hist | Cellul. | Multi/Atypia | Mitosis | CL | RC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | delTC1346 | 9 | FS449 | No | 45 | AL | ++ | ++/++ | + | Yes | |

| 2 | delA1164 | 8 | FS389 | Yes | 46 | AL | ++ | ++/++ | − | Yes | |

| 3 | G>C691 | 5 | A231P | Yes | 32 | L | ++ | +/++ | − | ||

| 4 | C>T172 | 2 | R58X | Yes | 25 | SMU | ++ | ++/++ | + | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | A>C191 | 2 | N64T | Yes | 35 | SMU | ++ | ++/++ | + | Yes | |

| 6 | G>A569 | 4 | R190H | Yes | 25 | AL | ++ | ++/++ | + | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | G>C691 | 5 | A231P | 41 | AL | ++ | +/+ | + | |||

| 8 | InsA1010 | 7 | FS337 | Yes | 30 | AL | ++ | +/+ | + | No | |

| 9 | DelA1164 | 8 | FS389 | Yes | 24 | AL | ++ | ++/++ | − | yes | |

| 10 | SpliceDonor+1 | 1 | None | No | 25 | CL | ++ | +/+ | − | No | |

| 11 | G>A569 | 4 | R190H | 39 | SMU | ++ | ++/++ | + | Yes | ||

| 12 | G>A1060 | 7 | G354R | Yes | 45 | AL | ++ | +/++ | − | ||

| 13 | T>C1126 | 8 | S376P | 40 | CL | ++ | +/+ | − | Yes | ||

| 14 | C>A1025 | 7 | A342D | 26 | AL | ++ | +/++ | + | Yes | Yes | |

| 15 | A>C1187 | 8 | Q396P | 47 | CL | ++ | +/+ | − | Yes | yes | |

| 16 | Under study | Not done | 30 | CL | ++ | ++/++ | + | ||||

| 17 | Under study | Not done | 35 | CL | ++ | ++/++ | − | ||||

| 18 | Under study | Not done | 40 | CL | ++ | +/+ | − | ||||

| 19 | Under study | Not done | 38 | CL | ++ | ++/++ | ++ |

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Characteristic histopathology of uterine leiomyomas in HLRCC. 1a,b: Atypical leiomyoma with marked nuclear atypia (H-Ex100). No evidence of mitosis was seen in this case (H-Ex200). 1c,d: Cellular leiomyoma showing interlacing bundles of smooth muscle fibers with centrally located long blunt-edged nuclei, occasional multinucleated cells and no mitotic figures (H-Ex100) (H-Ex200). 1e: Cellular leiomyoma with occasional mitosis present. 1f: IHC staining for MiB1 showed moderate proliferative activity in some cases (H-Ex100). 1g,h: High power of an atypical leiomyoma showing the large nuclei with prominent orangiophilic nucleoli and perinuclear clearing. These nuclear features are commonly in kidney cancer (H-Ex300) (H-Ex400).

Figure 1B(j,k)): Renal cell carcinoma showing papillary configuration and cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. A large nucleus with a prominent orangiophilic nucleolus surrounded by a perinucleolar halo is seen (H&E 100, H&E 150X)

The LOH analysis is shown in Table 1. Table 1 also shows for each individual type of the germline FH mutation, exon and codon affected by the mutation and the nucleotide and amino acid change. Different FH exons were affected with a higher incidence of exon 7 (3 cases) and 8 (4 cases) mutations. The LOH analysis demonstrated allelic loss in 8 out of 10 cases where DNA was available (80%). The figure 4 shows the LOH patterns detected with various markers flanking the FH gene. In cases where LOH was found, it was consistent with a partial loss of chromosome 1q43. The wide allelic loss was determined with all the informative microsatellite markers (arrows covering the deleted chromosomal region). Identical LOH patterns were found in different leiomyomas studied from the same patient (cases 2 and 4). Both, atypical leiomyomas and cellular leiomyomas were analyzed in case 2 and all showed the same LOH pattern (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

LOH at 1q43 in HLRCC uterine leiomyomas: The large transversal boxed with case# and diagnosis specification in the left side represent the 1q43 chromosomal region (Symbols: AL: atypia leiomyoma, CL: cellular leiomyoma, SMTUMP: smooth miscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential). The LOH analysis of different cell populations from the same patient is grouped with brackets when pertinent. The FH gene location and the microsatellite markers analyzed are represented as inner boxes inside the large box representing 1q43 chromosome. The name of the markers and the FH location are specified on the top of the figure. From left to right: D1S517, D1S2875, D1S180, FH gene with the AFM214 microsatellite marker within the sequence, D1S547 and D1S2842. In each case, the box representing each marker can appear as filled in black when LOH was detected, white for not informative results or empty when heterozygous. In cases where LOH was found, the wide allelic loss was determined with all the informative microsatellite markers (black arrows covering the deleted chromosomal region). Identical LOH patterns were found in different leiomyomas studied from the same patient (cases 2 and 4).

Discussion

The present study describes the morphologic changes found in the uterine smooth muscle tumors of female patients with HLRCC syndrome. Smooth muscle tumors associated with this syndrome occur predominantly in younger women who present with severe history of irregular bleeding that required hysterectomy. HLRCC leiomyomas frequently showed histopathological features consistent with cellular or atypical uterine leiomyomas. All cases showed tumor nuclei that contained inclusion-like nucleoli that were orangiophilic, with a perinucleolar halo similar to the changes found in HLRCC renal cancer nuclei.6 This histopathological feature can be considered the hallmark of both uterine leiomyomas and HLRCC renal cancer. In the original description of HLRCC, it was reported that two of eleven women with uterine leiomyomas also had uterine leiomyosarcoma.10 To date, six women with a germline mutation in FH have been reported with uterine leiomyosarcoma.26 In our series, no evidence of coagulative tumour cell necrosis or abnormal mitosis was found and the tumors did not fulfill the criteria for malignancy. One patient underwent two separate surgeries with an interval time of two years during which a pregnancy occur, but no morphologic changes were seen when the tumors were compared.

Clinically, previous reports describe that uterine leiomyomas are present in almost all females with HLRCC, tend to be numerous and large and are usually highly symptomatic.21,1,25 The young age of onset of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas and the high risk of hysterectomy significantly impact the childbearing years of women with HLRCC. The average age for hysterectomy in HLRCC patients was 30 year-old versus 45 years in the general population.21

The Krebs cycle enzyme, fumarate hydratase (FH), acts as tumor suppressor. Patients with HLRCC inherit a germline mutation of the FH gene as well as a wild-type copy. Uterine tumor formation appears to occur when there is a somatic alteration of the wild-type copy. That “second hit” in most HLRCC tumors seems to take the form of allelic loss of the wild-type allele, consistent with absent or near-absent protein function as the cause of tumorigenesis. The basic mechanism of tumorigenesis in HLRCC is likely to be pseudo-hypoxic drive, similarly to the molecular pathway described in VHL-deficient kidney cancer.22 Our study also reveals that smooth muscle tumors associated with HLRCC have characteristic genotypical features. LOH at 1q43 is frequent (80%) in HLRCC leiomyomas suggesting a biallelic inactivation of the FH gene, one allele inactivated by the germline mutation and the other by LOH. The explanation for a “second hit” inactivating FH in the remaining cases where no LOH was found could be either a second mutation in the coding sequence, non detected small deletions or hypermethylation of the promoter region. Both, FH mutations and LOH at 1q43 are genotypical features unusual in sporadic leiomyomas. Two studies showed no evidence of FH somatic mutations in 129 and 41 non-syndromic leiomyomas.2,9 LOH analysis performed by Lehtonen et al., found allelic loss at 1q43 in only 5 out of 153 sporadic cases. Therefore, the loss of function of the fumarate hydratase gene, inactivating its potential role as a tumor suppressor gene in tumorigenesis and activating the pseudo-hypoxic molecular pathway, seems to be more frequent in HLRCC leiomyomas than in sporadic leiomyomas. Indeed, expression profiling studies by cDNA microarrays have shown that FH-mutant leiomyomas have a distinct expression profile of genes belonging to groups such as glycolysis, extracellular matrix, cell growth, cell adhesion or muscle development when compared with sporadic wild-type FH gene leiomyomas.23 We conclude that uterine leiomyomas associated with HLRCC syndrome have characteristic morphologic features. Both, uterine leiomyomas and renal cancer cells share some morphological nuclear changes and genotypical features in HLRCC patients. The specific morphological features of the uterine leiomyomas we describe may be helpful additional features to identify patients that may undergo genetic testing for germline FH mutations and screening for renal cell cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ms. Christine Hall and Dr. Vladimir Valera Romero for their assistance with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alam NA, Leigh IM. Fumarate hydratase mutations and predisposition to cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas and renal cancer. British Journal Dermatology. 2005 Jul;153(1):11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker KT, Bevan S, Wang R, et al. Low frequency of somatic mutations in the FH/multiple cutaneous leiomyomatosis gene in sporadic leiomyosarcomas and uterine leiomyomas. British Journal of Cancer. 2002;87:446–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catherino WH, Mayers CM, Mantzouris T, et al. Compensatory alterations in energy homeostasis characterized in uterine tumors from hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Fertility Sterility. 2007 Mar 23;88(2):1039–48. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher CF World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology And Genetics of Tumours of the Soft Tissues And Bones. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross KL, Panhuysen CI, Kleinman MS, et al. Involvement of fumarate hydratase in nonsyndromic uterine leiomyomas: genetic linkage analysis and FISH studies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;41:183–90. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubb RL, 3rd, Franks ME, Toro J, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. Journal of Urology. 2007 Jun;177(6):2074–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacs JS, Mole DR, Torres-Cabala C, et al. HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell. 2005 Aug;8(2):143–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiuru M, Launonen V, Hietala M, et al. Familial cutaneous leiomyomatosis is a two-hit condition associated with renal cell cancer of characteristic histopathology. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;159:825–829. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61757-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiuru M, Lehtonen R, Arola J, et al. Few FH mutations in sporadic counterparts of tumor types observed in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer families. Cancer Research. 2002;62:4554–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al. Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proceedings National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98:3387–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051633798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehtonen R, Kiuru M, Vanharanta S, et al. Biallelic inactivation of fumarate hydratase (FH) occurs in nonsyndromic uterine leiomyomas but is rare in other tumors. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164:17–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63091-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehtonen H, MŠkinen MJ, Kiuru M, et al. Increased HIF1 in SDH and FH deficient tumors does not cause microsatellite instability. International Journal of Cancer. 2007 May 22; doi: 10.1002/ijc.22819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linehan WM, Vasselli J, Srinivasan R, et al. Genetic basis of cancer of the kidney: disease-specific approaches to therapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10:6282S–9S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez-Mir A, Glaser B, Chuang GS, et al. Germline fumarate hydratase mutations in families with multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomata. Journal Investigative Dermatology. 2003;121:741–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto PA, et al. The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. American Journal Surgical Pathology. 2007;31(10):1578–85. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31804375b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pithukpakorn M, Wei MH, Toure O, et al. Fumarate hydratase enzyme activity in lymphoblastoid cells and fibroblasts of individuals in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. (Letter) Journal Medical Genetics. 2006;43:755–762. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratcliffe PJ. Fumarate hydratase deficiency and cancer: activation of hypoxia signaling. Cancer Cell. 2007 Apr;11(4):303–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed WB, Walker R, Horowitz R. Cutaneous leiomyomata with uterine leiomyomata. Acta Dermatologica Venereologica. 1973;53:409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudarshan S, Pinto PA, Neckers L, et al. Mechanisms of disease: hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer--a distinct form of hereditary kidney cancer. Nature Clinical Practice Urology. 2007 Feb;4(2):104–10. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudarshan S, Sourbier C, Kong HS, et al. Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and HIF-1 alpha stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Molecular Cell Biology. 2009 May 26;15:4080–90. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00483-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. American Journal Human Genetics. 2003;73:95–106. doi: 10.1086/376435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomlinson IPM, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, et al. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine leiomyomas, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nature Genetics. 2002;30:406–410. doi: 10.1038/ng849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanharanta S, Pollard PJ, Lehtonen HJ, et al. Distinct expression profile in fumarate-hydratase-deficient uterine leiomyomas. Human Molecular Genetics. 2006 Jan 1;15(1):97–103. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Virchow R. Über Makroglossie und pathologische neubildung quergestreifter Muskelfasern. Virchows Archives Pathologic Anatomy. 1854;7:126–138. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei M-H, Toure O, Glenn GM, et al. Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Journal Medical Genetics. 2006;43:18–27. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ylisaukko-oja SK, Kiuru M, Lehtonen HJ, et al. Analysis of fumarate hydratase mutations in a population-based series of early onset uterine leiomyosarcoma patients. International Journal Cancer. 2006;119(2):283–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]