Abstract

Objective To characterise the functional morphology of the nasal microcirculation in humans in comparison with reindeer as a means of testing the hypothesis that the luminous red nose of Rudolph, one of the most well known reindeer pulling Santa Claus’s sleigh, is due to the presence of a highly dense and rich nasal microcirculation.

Design Observational study.

Setting Tromsø, Norway (near the North Pole), and Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Participants Five healthy human volunteers, two adult reindeer, and a patient with grade 3 nasal polyposis.

Main outcome measures Architecture of the microvasculature of the nasal septal mucosa and head of the inferior turbinates, kinetics of red blood cells, and real time reactivity of the microcirculation to topical medicines.

Results Similarities between human and reindeer nasal microcirculation were uncovered. Hairpin-like capillaries in the reindeers’ nasal septal mucosa were rich in red blood cells, with a perfused vessel density of 20 (SD 0.7) mm/mm2. Scattered crypt or gland-like structures surrounded by capillaries containing flowing red blood cells were found in human and reindeer noses. In a healthy volunteer, nasal microvascular reactivity was demonstrated by the application of a local anaesthetic with vasoconstrictor activity, which resulted in direct cessation of capillary blood flow. Abnormal microvasculature was observed in the patient with nasal polyposis.

Conclusions The nasal microcirculation of reindeer is richly vascularised, with a vascular density 25% higher than that in humans. These results highlight the intrinsic physiological properties of Rudolph’s legendary luminous red nose, which help to protect it from freezing during sleigh rides and to regulate the temperature of the reindeer’s brain, factors essential for flying reindeer pulling Santa Claus’s sleigh under extreme temperatures.

Introduction

The nasal microcirculation has important physiological roles such as heating, filtering, and humidifying inhaled air, controlling inflammation, transporting fluid for mucous formation, and delivering oxygen to the nasal parenchymal cells. The pathophysiology of many nasal conditions, such as congestion and epistaxis, is based on the regulatory mechanisms of the microcirculation. Moreover, the nasal mucosa plays an important part in the uptake of drugs and responses to allergens. Despite the important role of nasal mucosa in health and disease, few studies have dealt with the function and morphology of its microcirculation in humans. Studies have been hampered mainly by the unavailability of techniques suitable for assessing the nose and by difficulties with nasal access from cumbersome microscopes. Some early studies used laser Doppler flowmetry,1 2 3 4 but most information on the microcirculation of the healthy and diseased human nose is from immunohistochemical studies on biopsied material.5 6

The introduction of hand-held intravital video microscopes has enabled direct visualisation of the nasal microcirculation in humans.7 8 9 These imaging instruments have had a special impact on intensive care medicine as they have shown the nasal microcirculation to be the most sensitive haemodynamic indicator of outcome and response to treatment.9 10 11 12 These instruments have also identified the microcirculation as a key factor in a wide range of other diseases, including diagnostic support and treatment responses in oncology.13 14 15

Using the novel technique of hand-held vital video microscopy we characterised the microvasculature of the human nose and applied the same technique to reindeer for comparative purposes. Based on the central role of the nasal microcirculation16 17 18 19 in the temperature regulation of reindeers’ brain and an appreciation of the importance of this for flying reindeer who have to deal with extremes of temperature while pulling a sleigh, we hypothesised that the infamous red nose of the most well known of Santa Claus’s reindeers, Rudolph, would originate from a rich vascular anatomy with a high functional density of microvessels.

Methods

Human volunteers

We recruited five consecutive volunteers from the department of otorhinolaryngology in the Academic Medical Center. Inclusion criteria were adult non-smokers aged 18 years or more with no history of systemic or nasal disease and who were not taking prescribed drugs. A short medical history was obtained from the volunteers before investigations began. Moreover, vascular reactivity of the nasal mucosa was tested in one of the healthy volunteers by local application of 100 mg cocaine,2 a drug routinely used in ear, nose, and throat medicine as a local anaesthetic and vasoconstrictor. Also, we evaluated the utility of hand-held video microscopy to identify irregular microcirculatory networks in nasal disease by assessing a patient with grade 3 polyposis.

Reindeer

Measurements were carried out at room temperature (18°C (SD 1°C)) on two adult reindeer (Rangifer tarandus, fig 1) under light anaesthesia using a single intramuscular injection of 0.2 mg/kg medetomidine hydrochloride (Zalopine; Orion, Espoo, Finland) delivered by a dart syringe.20 We used the hand-held microscope to video record and quantify the properties of the nasal microcirculation.21 22 Anaesthesia was terminated by an intramuscular injection of 0.7 mg/kg atipamezole hydrochloride (Antisedan; Orion).

Fig 1 Reindeer in Norwegian arctic region showing distinct pink coloration at tip of nose. Reproduced with permission of Kia Krarup Hansen

Microvascular imaging technique, measurements, and analysis

The microcirculation was imaged using a hand-held intravital video microscopy system (sidestream dark field imaging technology).8 One investigator (AMvK) obtained clinical measurements of the volunteers in one room kept at a constant temperature of 22°C (SD 1°C). Participants were seated upright in a chair with their head on a headrest. We measured the microcirculation of the reindeer in a similar manner to the clinical measurements by gently inserting the imaging probe, covered with a sterile disposable lens cover, into the nasal cavity.

Offline data analysis was by semi-automated microvascular imaging software developed by our group.22 We quantified the vascular density of blood vessels <25 μm to determine the perfused vessel density (mm vessel/mm2) and the microvascular flow index: absent (0), intermittent (1), sluggish (2), or normal (3).21

Statistical analysis

A Mann-Whitney test was used for non-parametric comparative analysis of perfused vessel density and microvascular flow index. We considered P values of differences less than 0.05 to be significant. Data are presented as means (standard deviations).

Results

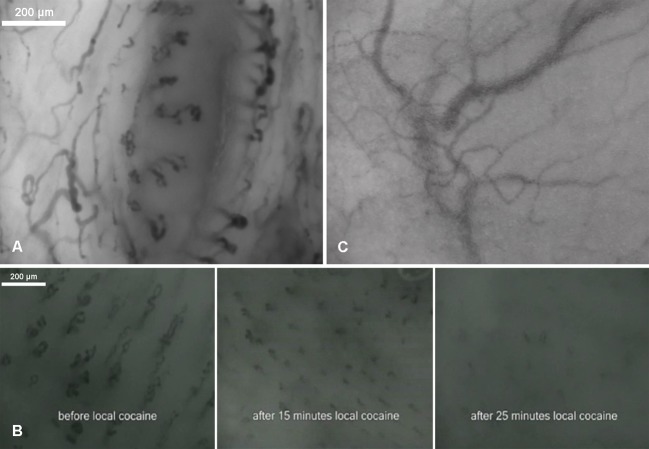

Five healthy volunteers (four men and one woman, mean age 30 (SD 8) years), of which one was exposed to a cocaine challenge to test vascular reactivity of the nasal mucosa, and a male patient with grade 3 nasal polyposis agreed to participate in the study. In all volunteers the contrast of the nasal mucosa was enough to visualise the microcirculation, which consisted of flowing red blood cells (fig 2; also see the supplementary video recording). High quality images were obtained from the nasal septum and the inferior turbinate. None of the volunteers experienced discomfort or pain during imaging. The plexus, or Kiesselbach’s area, was clearly visible in the anterior nasal septum (fig 2). Discrete, circularly arranged capillaries were observed throughout the nasal mucosa in all the healthy volunteers. The capillaries contained a central lumen-like structure (large circular structure in fig 2) and were observed at different locations throughout the nasal septum. The central circular structure seemed to be a gland for the excretion of mucous. Quantification of the nasal microcirculation in the healthy volunteers showed a mean perfused vessel density of 15 (SD 3.2) mm/mm2 with a microvascular flow index of 3.0 arbitrary units.

Fig 2 Microcirculation in anterior septum of healthy human volunteers (panel A), showing hairpin-like vessels in a circular configuration. The before and after vascular reactivity test shows a decrease from baseline vascular density and perfusion after application of cocaine (panel B). Hairpin-like vasculature was absent in the grade 3 nasal polyp (panel C)

The microvasculature of the inferior turbinate presented a characteristic hairpin-like morphology analogous to other mucosal tissue surfaces. The arrangement of the capillaries varied with location, with only the tops or arches of the loops visible in some areas and the entire loop structure with its afferent and efferent arms visible in other areas. The images consistently portrayed capillaries but no large blood vessels; big venous structures could be observed only out of focus (fig 2). In addition, the configuration of the vasculature surrounding the gland-like structures on the inferior turbinate was the same as that of other capillary loops found in other mucosal tissue surfaces.

A transitory cessation of microcirculatory flow was observed in the healthy volunteer after a vasoconstrictor challenge using cocaine (fig 2). In addition, the nasal microvasculature of the patient with nasal polyposis was irregular and the characteristic angioarchitecture and hairpin-like capillaries were absent (fig 2).

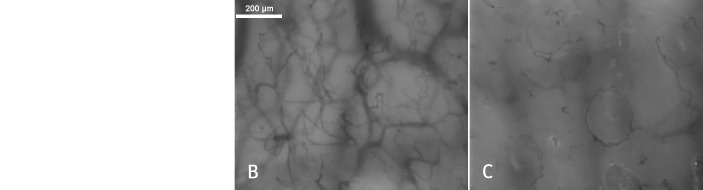

Why Rudolph’s nose is red

The reindeer’s nasal mucosa was richly vascularised with an abundant microcirculation ferrying a rich concentration of red blood cells; the mean perfused vessel density was 20 (0.7 mm/mm2) with a microvascular flow index of 3.0 arbitrary units (fig 3). An infrared thermographic image of the reindeer obtained with an AGA Thermovision IR camera (Model 750 (spectral range 2-5 µm)) connected to an AGA Thermovision Colour Slave Monitor (Model OM 701; AGA, Stockholm, Sweden) after a treadmill test showed that they do indeed have red noses.23 In addition to the nose having a high microvascular density (fig 3), the nasal mucosa also revealed an abundance of ring-like vascular arrangements, similar to those in humans (fig 3).

Fig 3 Infrared image of a reindeer’s head after a treadmill test shows the presence of a red nose (arrow, panel A).23 Colours represent different temperatures: blue 15°C, white 19°C, and red 24°C. The dark band is the harness. Real time intravital video microscopy images of reindeer nasal microcirculatory network with hairpin-like (panel B) and related ring-like vasculature (panel C), similar to human nasal microcirculation. Reproduced with permission of the Department of Arctic and Marine Biology, University of Tromsø

The microvascular networks and hairpin-like vessels of the nasal microcirculation in reindeer were similar to those observed in humans. The functional vascular density of the reindeers’ nasal mucosa was 25% higher than that in humans (fig 3). Interestingly, the reindeers’ microcirculation was pumped in pulsatile intervals with a complete lack of red blood cells in the lumen of the microvasculature during diastole followed by forceful flow hyperaemia during systole. As this effect cannot be properly justified in a static image, we produced a video recording (see supplementary material).

Discussion

The microcirculation of the nasal mucosa in reindeer is richly vascularised and 25% denser than that in humans. These factors explain why the nose of Rudolph, the lead flying reindeer employed by Santa Claus to pull his sleigh, is red and well adapted to carrying out his duties in extreme temperatures.

Intravital video microscopy allowed observation of the complex architecture of the nasal microcirculation, including the kinetics of flowing red blood cells, and provided new insights into the adaptive behaviour of vascular structures under varying clinical conditions. An interesting finding was the presence of gland-like structures in the nasal mucosa. The most plausible explanation for the function of these circular vascular structures is mucous secretion. These structures are scattered throughout the nose and maintain an optimal nasal climate during humid weather and extremes of temperature as well as being responsible for fluid transport and acting as a barrier. Such structures were also identified in the two reindeer, although the vascularisation was slightly different and of a higher density than in the human volunteers. Histological studies would need to be carried out to determine the exact function of these gland-like structures.

Despite successfully imaging the nasal microcirculation of both the human volunteers and the reindeer, we were limited by the diameter of the light guide on the video microscope (1 cm), at least in the humans, and could obtain measurements on only certain nasal surfaces. Further miniaturisation of the dimensions of nasal endoscopes and conventionally used imaging probes for video microscopy should resolve this limitation, allowing a more comprehensive evaluation of the nasal microcirculation. These practical concerns may be resolved by the introduction of a third generation hand-held intravital imaging computer controlled sensor based microscope.9

Conclusions

Using hand-held vital video microscopy for imaging the human nasal microcirculation in health, interventions, and disease, we were able to solve an age old mystery. Rudolph’s nose is red because it is richly supplied with red blood cells, comprises a highly dense microcirculation, and is anatomically and physiologically adapted for reindeer to carry out their flying duties for Santa Claus.

What is already known on this topic

The introduction of hand-held intravital video microscopes has enabled direct visualisation of the microcirculation in human organs but has not previously been applied to the nasal microcirculation

These instruments could be used to unlock the mystery of why Rudolph, the legendary flying reindeer, has a bright red nose

What this study adds

The nasal microcirculation in humans consists of hairpin-like vessels, microcirculatory networks, and crypt-like structures surrounded by capillaries

By comparison, reindeer have a more richly vascularised nasal microcirculation, with a vascular density 25% higher than that in humans

This high vascular density answers the age old mystery of why Rudolph has a bright red nose

We thank Santa Claus for his enthusiastic support. He was as keen as us to unravel the mystery of his friend’s nose.

Contributors: CI conceived, designed, and supervised the study and together with AMvK drafted the manuscript. They contributed equally to the study. AMvK, DMJM, and KY analysed and interpreted the data and performed the statistical analysis. WJF supervised and evaluated the clinical study. LPF and ASB designed and performed the study on reindeer. All authors had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript. Rick Bezemer of the Department of Translational Physiology of the Academic Medical Center vouches for the validity of the study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; CI is the inventor of sidestream dark field imaging technology and holds shares in MicroVision Medical and was a consultant for this company more than four years ago but has had no further contact with the company since then. He has no other competing interests in this field other than his commitment to promoting the importance of the microcirculation during patient care; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Academic Medical Centre of the University of Amsterdam for the human study and the Norwegian Animal Research Authority of Norway for the reindeer experiments (Permit No 4414).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;345:e8311

References

- 1.Druce HM, Kaliner MA, Ramos DF, Bonner RF. Measurement of multiple microcirculatory parameters in human nasal mucosa using laser-Doppler velocimetry. Microvasc Res 1989;38:175-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grudemo H, Juto JE. Rhinostereometry and laser Doppler flowmetry in human nasal mucosa: changes in congestion and microcirculation during intranasal histamine challenge. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 1997;59:50-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grudemo H, Juto JE. Studies of spontaneous fluctuations in congestion and nasal mucosal microcirculation and the effects of oxymetazoline using rhinostereometry and micromanipulator guided laser Doppler flowmetry. Am J Rhinol 1999;13:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cervin A, Akerlund A, Greiff L, Andersson M. The effect of intranasal budesonide spray on mucosal blood flow measured with laser Doppler flowmetry. Rhinology 2001;39:13-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abrams DC, Toynton SC, Dore C, Emson MA, Taylor P, Springall DR, et al. Stereological estimation of blood vessel surface and volume densities in human normal and rhinitic nasal mucosa. Rhinology 1997;35:22-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Philpott CM, Wild D, Guzail M, Murty GE. Variability of vascularity in nasal mucosa as demonstrated by CD34 immunohistochemistry. Clin Otolaryngol 2005;30:373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groner W, Winkelman JW, Harris AG, Ince C, Bouma GJ, Messmer K, et al. Orthogonal polarization spectral imaging: a new method for study of the microcirculation. Nat Med 1999;5:1209-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goedhart PT, Khalilzada M, Bezemer R, Merza J, Ince C. Sidestream Dark Field (SDF) imaging: a novel stroboscopic LED ring-based imaging modality for clinical assessment of the microcirculation. Opt Express 2007;15:15101-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezemer R, Bartels SA, Bakker J, Ince C. Clinical review: clinical imaging of the microcirculation in the critically ill—where do we stand? Crit Care 2012;16:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spronk PE, Ince C, Gardien MJ, Mathura KR, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Zandstra DF. Nitroglycerin in septic shock after intravascular volume resuscitation. Lancet 2002;360:1395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakr Y, Dubois MJ, De Backer D, Creteur J, Vincent JL. Persistent microcirculatory alterations are associated with organ failure and death in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1825-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ince C. The microcirculation is the motor of sepsis. Crit Care 2005;9(Suppl 4):S13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathura KR, Bouma GJ, Ince C. Abnormal microcirculation in brain tumours during surgery. Lancet 2001;358:1698-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meinders AJ, Elbers P. Images in clinical medicine. Leukocytosis and sublingual microvascular blood flow. N Engl J Med 2009;360:e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milstein DM, te Boome LC, Cheung YW, Lindeboom JA, van den Akker HP, Biemond BJ, et al. Use of sidestream dark-field (SDF) imaging for assessing the effects of high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation on oral mucosal microcirculation in myeloma patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010;109:91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blix AS, Johnsen HK. Aspects of nasal heat exchange in resting reindeer. J Physiol 1983;340:445-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blix AS, Walloe L, Folkow LP. Regulation of brain temperature in winter-acclimatized reindeer under heat stress. J Exp Biol 2011;214:3850-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aas-Hansen O, Folkow LP, Blix AS. Panting in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2000;279:R1190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnsen HK, Blix AS, Jørgensen L, Mercer JB. Vascular basis for regulation of nasal heat exchange in reindeer. Am J Physiol 1985;249:R617-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blix AS, Lian H, Ness J. Immobilization of muskoxen (Ovibus moscatus) with etorphine and xylazine. Acta Vet Scand 2011;53:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boerma EC, Mathura KR, van der Voort PH, Spronk PE, Ince C. Quantifying bedside-derived imaging of microcirculatory abnormalities in septic patients: a prospective validation study. Crit Care 2005;9:R601-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobbe JGG, Streekstra GJ, Atasever B, van Zijderveld R, Ince C. Measurement of functional microcirculatory geometry and velocity distributions using automated image analysis. Med Biol Eng Comput 2008;46:659-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blix AS. Arctic animals. Tapir Academic Press, 2005.