Abstract

Rationale

The lipid phosphate phosphatase 3 (LPP3) degrades bioactive lysophospholipids including lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and thereby terminates their signaling effects. While emerging evidence links LPA to atherosclerosis and vascular injury responses, little is known about the role of vascular LPP3.

Objective

The goal of this study was to determine the role of LPP3 in the development of vascular neointima formation and smooth muscle cells (SMC) responses.

Methods and Results

We report that LPP3 is expressed in vascular SMC following experimental arterial injury. Using gain- and loss-of-function approaches, we establish that a major function of LPP3 in isolated SMC cells is to attenuate proliferation, (ERK) activity, Rho activation, and migration in response to serum and LPA. These effects are at least partially a consequence of LPP3-catalyzed LPA hydrolysis. Mice with selective inactivation of LPP3 in SMC display an exaggerated neointimal response to injury.

Conclusions

Our observations suggest that LPP3 serves as an intrinsic negative regulator of SMC phenotypic modulation and inflammation after vascular injury, in part by regulating lysophospholipid signaling. These findings may provide a mechanistic link to explain the association between a PPAP2B polymorphism and coronary artery disease risk.

Keywords: intima, smooth muscle cells, restenosis, proliferation, LPP3

Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells (SMC) occurs in response to vascular injury and is a critical component of the development of intimal hyperplasia, a defining feature of atherosclerotic and restenotic lesions 1, 2. Lysophosphatidic acid is a key component in serum 3 that promotes dedifferentiation 3–5, proliferation 6, 7, and migration 8–11 of cultured SMC. Based on SMC responses to LPA, and the related lysopholipid sphingosine-1-phoshate (S1P), these lipid mediators have been proposed to regulate SMC phenotypic modulation and the development of intimal hyperplasia in vivo. Both LPA and S1P elicit cellular effects through G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). In the case of LPA, at least six and potentially eight, GPCRs exist that act through Gi, G12/13, Gq, and Gs to stimulate intracellular signaling pathways to modulate cAMP production 12, 13, the activity of phospholipase D (PLD) activity, Rho GTPases 14; phospholipase C (PLC) and protein kinase C (PKC) 15; extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 16; and the initiation of Ca2+-transients 17. Similar complex signaling systems exists for S1P18, 19. Evidence from studies using genetic and pharmacologic approaches to target specific LPA and S1P receptors, supports their role in regulating neointimal growth in response to vascular injury in mice. The development of intimal hyperplasia likely results from effects of LPA or S1P on multiple cell types, including recruitment of inflammatory and progenitor cells and stimulation of resident SMC 4, 20–25. Moreover, LPA heightens atherosclerotic plaque burden in apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice in an LPA1- and LPA3-dependent manner 26.

The signaling actions of LPA, and potentially S1P, can be terminated by enzymatic dephosphorylation catalyzed by lipid phosphate phosphatases, which are cell surface integral membrane proteins. LPP3, encoded by the Ppap2b gene, is essential in mice for vascular development and gastrulation 27 and is expressed during development in heart cushions and valves 28. Studies in cultured cells implicate LPP3 as both a regulator of vascular cell LPA responsiveness and a ligand for integrin αVβ3 29, 30. However, because of the early embryonic lethality observed in mice lacking LPP3, a specific role for the enzyme in vascular cell function remains unknown. The identification of PPAP2B among 13 loci recently associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) in humans 31 suggests a causal relationship between LPP3 and vascular disease susceptibility.

In the present work, we identified SMC as a source of vascular LPP3 expression and sought to define a pathophysiologic role for SMC LPP3 in adult vascular tissue. We used genetic approaches to alter LPP3 expression and activity in SMC and investigate the consequences on vascular injury and isolated cellular responses. Using gain and loss-of-function approaches, we provide evidence that LPP3 regulates lysophospholipid signaling responses in SMC. Our findings implicate both LPP3 and lysophospholipids as pathophysiologically important regulators of SMC biology and may provide mechanistic insight into the association of an intronic single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in PPAP2B with CAD risk.

METHODS

(Note: An expanded Materials and Methods section is available in the supplementary data.)

Mice

All procedures conformed to the recommendations of Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication number NIH 78-23, 1996), and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The production and initial characterization of mice in which the Ppap2b gene encoding LPP3 was flanked by lox-P sites (Ppap2bfl/fl) has previously been described 32, 33. Ppap2bfl/fl mice were backcrossed for >10 generations to the C57Bl/6 background and then crossed with C57Bl/6 mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the SM22 promoter 34 to obtain congenic SM-Ppap2bΔ mice. The mice survived in the expected numbers. Mating of homogzygous Ppap2bfl/fl with SM-Ppap2bΔ mice yielded 50% SM-Ppap2bΔ offspring with less than 2% mortality. Mice were housed in cages with HEPA-filtered air in rooms on 12-hour light cycles and fed Purina 5058 rodent chow ad libitum. Systolic blood pressure and heart rate were measured for five consecutive days noninvasively in conscious mice using the CODA blood pressure analysis tail cuff system (Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT) daily after training for one week. Mean intra-arterial pressure was measured by placement of a 1.4 Fr Millar catheter in the carotid artery of isoflurane-anesthetized mice.

Vascular Injury

The left common carotid artery was dissected and ligated near the carotid bifurcation. All animals recovered and showed no symptoms of a stroke. At various intervals after carotid surgery 35, 36, 5 mm of carotid proximal to the suture were removed and processed for RNA analysis by qualitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or analysis of protein markers by immunoblotting. Neointimal formation along the length of the vessel was assessed at four weeks after surgery using computer assisted morphometry as previously described 36. Digital images were taken with a high-performance digital camera (resolution 3,840 × 3,072 pixels) attached to a Nikon 80i microscope with an X10 (NA = 0.3) or X20 (NA = 0.5) objective lens and analyzed with Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as mean ± SD. In vitro studies were repeated a minimum of 3 times, and results were analyzed by Student t test or Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma-STAT software version 3.5 (Aspire Software, International, Ashburn, VA). A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

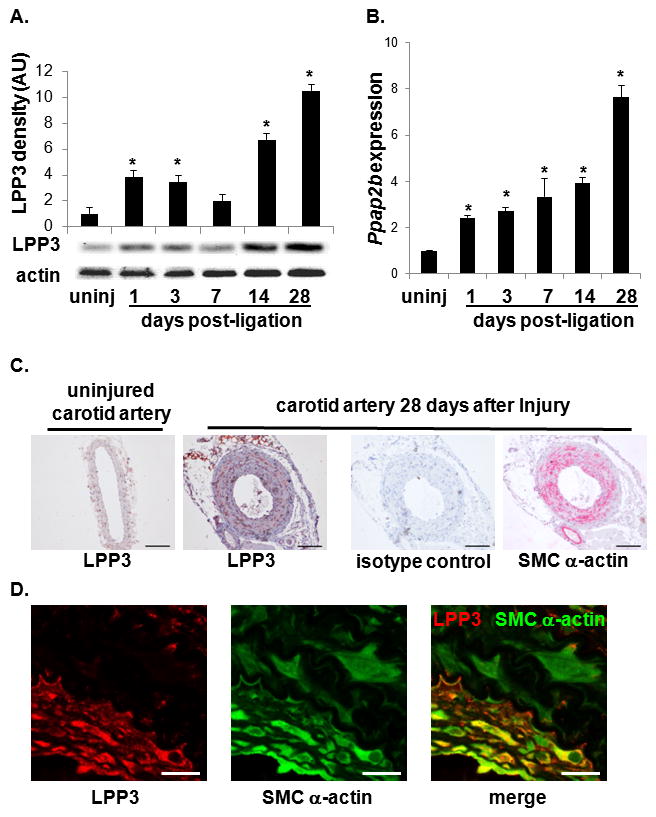

Upregulation of LPP3 in neointimal regions following vascular injury

As an initial approach to understanding the role of LPP3 in vascular disease, we profiled LPP3 expression in blood cells and in arterial vessels before and after vascular injury. Polymorphonuclear cells, but not other leukocytes or platelets, express detectable levels of LPP3 (Supplemental Figure 1). In carotid arteries, LPP3 expression was markedly upregulated in neointimal regions after ligation injury (Figure 1). LPP3 protein (Figure 1A) and mRNA levels (Figure 1B) in carotid arteries were higher most notable ≥ 14 days after injury. To localize LPP3 expression in injured vessels, immunostaining for LPP3 and the SMC α-actin marker was performed (Figure 1C and 1D). The findings indicated that LPP3 expression co-localized in areas that contain SMCs after arterial injury (Figure 1C, brown staining) and, in particular, in the neointimal region at 28 days after injury (Figure 1D, yellow overlap). These results suggest that SMC are at least one source of neointimal LPP3. Indeed, isolated, cultured SMC from murine aorta expresses LPP3 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1. LPP3 expression in carotid artery following vascular ligation injury.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of LPP3 expression in uninjured (uninj) and post-ligation carotid artery at the indicated times. Actin was used as a loading control. LPP3 expression was normalized to actin staining (n = 3 animals per time point) and graphed as mean ± SD in arbitrary units in which the density of LPP3 in the uninjured samples were set to 1. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA. (B) Gene expression analysis for Ppap2b (encoding LPP3) in carotid artery samples post-ligation. Values are expressed as a fold increase over uninjured and graphed as mean ± SD from n = 3 animals per time point. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA. (C) Immunostaining for LPP3 in uninjured and in carotid artery at 28 d after injury. A control antibody and SMC α-actin staining of 28 d post-injury vessels are included for reference. Bar = 100 μm. (D) Higher magnification (100X) images from carotid arteries four weeks after surgery taken ≈ 1.2mm from the site of ligation. Sections were double stained for LPP3 (red) and SMC a-actin (green). Bar denotes 20 μm.

LPP3 negatively regulates LPA signaling responses in SMC

The LPP family of cell-surface-associated lipid phosphatases hydrolyzes and inactivates LPA and the related lysophospholipid S1P. Both bioactive lipids have been implicated as mediators of phenotypic modulation of vascular SMC responses in vivo and in vitro. The time-course of upregulation of LPP3 expression in injured vessels is consistent with a role for the enzyme in down-regulating lipid signaling and thereby halting lysophospholipid -mediated inflammation, proliferation, and migration. We used isolated SMC to test the hypothesis that LPP3 alters SMC responses by attenuating LPA-mediated signaling. LPP3 was overexpressed in SMC using a recombinant lentiviral vector (Supplemental Figure 2A). In comparison to control cells infected with GFP-expressing virus, LPP3-overexpressing SMC cultured in serum (which contains μM levels of LPA), displayed ≈ 2-fold less growth after six days (P<0.05; Supplemental Figure 2B). The effect of LPP3 was specific in that overexpression of LPP3 had no effect on growth in response to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). In cells cultured in serum, LPP3 overexpression reduced ERK activity by ~ 50% (Supplemental Figure 2C and D) and Rho activity by ~ 75% (Supplemental Figure 2E). LPP3 also attenuated LPA-stimulated ERK activation (Supplemental Figure 2D) and prevented migration of cells in response to LPA (Supplemental Figure 2F). These effects were not observed in cells overexpressing a catalytically inactive LPP3 mutant (Supplemental Figure 2D and 2F), indicating that the lipid phosphatase activity of LPP3 is required to attenuate SMC responses.

Next, the consequences of LPP3 deficiency on LPA signaling in SMC were determined by generating mice lacking SMC LPP3. This was accomplished by crossing mice in which exon 3 and 4 of the Ppap2b locus (encoding LPP3) was flanked by loxP sites (Ppap2bfl/fl) with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the SM22 promoter (SM22-Cre) to generate SMC-LPP3-deficient mice (SM-Ppap2bΔ). SM-Ppap2bΔ mice are viable and fertile with no obvious phenotypic abnormalities. Immunoblot analysis of aortic SMC confirmed the absence of LPP3 in the aorta of SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (Supplemental Figure 3A). In SMC from SM-Ppap2bΔ mice, LPA phosphatase activity associated with LPP3 was <10% of that observed in cells from Ppap2bfl/fl mice (Supplemental Figure 3B), and levels of LPP3 identified in immunoprecipates from cultured aortic SMC were also reduced (Supplemental Figure 3C).

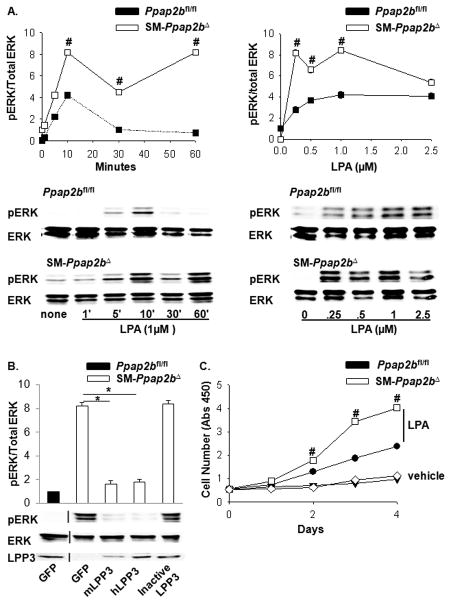

The absence of LPP3 in SMC promoted LPA-mediated ERK activation by increasing and prolonging ERK phosphorylation (Figure 2A). In comparison to Ppap2bfl/fl cells, SM-Ppap2bΔ cells demonstrated an ≈ 2-fold increase in LPA-induced ERK activation that persisted for up to 60 minutes (P<0.001; Figure 2A left). Additionally, SM-Ppap2bΔ cells responded to lower levels of LPA, with an ≈ 3-fold increase in ERK activation at 10 minutes in response to 0.25 μM LPA (P<0.001; Figure 2A right). Expression of murine or human LPP3, but not a catalytically inactive LPP3 mutant, rescued the phenotype of SM-Ppap2bΔ cells by reducing phosphorylation of ERK in response to LPA (Figure 2B). Consistent with these observations, LPP3 deficiency in SMC resulted in a 1.9-fold increase in LPA-mediated proliferation (P<0.001; Figure 2C), which was not due to a non-specific enhancement of proliferation, as responses to PDGF were unaffected (not shown).

Figure 2. LPP3 deficiency enhances ERK activity and SMC proliferation.

(A) Time course (left) of 1 μm LPA- stimulated ERK activation in SMC isolated from Ppap2bfl/fl (dark squares) and SM-Ppap2bΔ (open squares) mice and dose-response curve at 10 min (right). Results are presented as the ratio of pERK/total ERK (mean ± SD) from 4 separate experiments with the value observed in the absence of LPA set as 1. Representative immunoblots are presented under the graphed data. (B) Lentivirus-mediated expression of mouse (m) or human (h) LPP3 in SMC attenuated ERK activation in aortic SMC from SM-Ppap2bΔ mice. (C) Growth curves, measured by WST-1 cell proliferation assay, for SMC in the absence (vehicle) or presence of 1 μM LPA. Results are presented as mean ± SD from 3 independent cultures of SMC of each genotype. # P<0.001 by t-test versus control. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

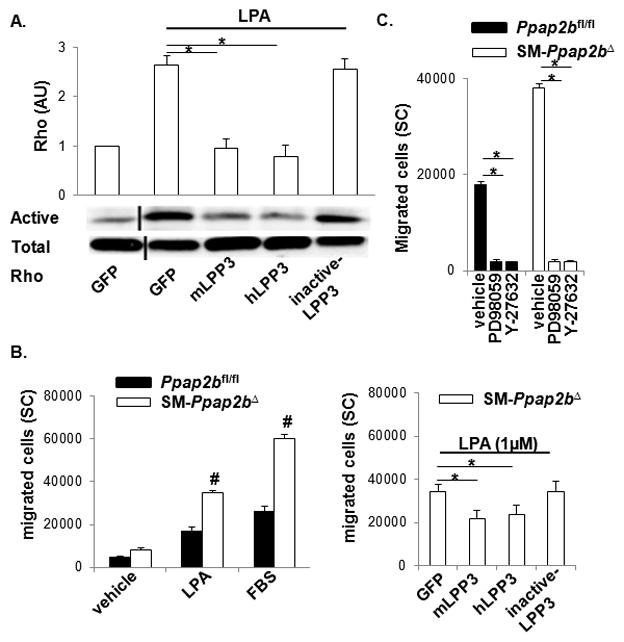

Rho activation in response to LPA was also enhanced in SM-Ppap2bΔ cells (P<0.001) and was corrected by overexpression of either murine or human LPP3, but not a catalytically inactive mutant (Figure 3A). In keeping with heightened ERK and Rho activation, SMC-lacking LPP3 demonstrated a 2.3-fold increase in migration towards either LPA or fetal bovine serum (P<0.001; Figure 3B). Migration of SM-Ppap2bΔ cells was reduced to levels observed in Ppap2bfl/fl cells by re-expression of either murine or human LPP3 (Figure 3C), and abolished by Rho kinase and ERK inhibitors (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Rho activity and SMC migration is enhanced by LPP3 deficiency.

(A) Active Rho in pull down assays was expressed as a ratio of total Rho in arbitrary units (AU), with the value in vehicle-treated cells set as 1. Results are presented as mean ± SD. SMC from Ppap2bfl/fl were infected with lentivirus expressing GFP, mouse (m), or human (h) LPP3 or a catalytically inactive variant of the enzyme. SMC were treated with 1 μm LPA for 10 min before assaying Rho activity. (B) The number of Ppap2bfl/fl (closed bars) and SM-Ppap2bΔ (open bars) cells migrating towards vehicle, 1 μm LPA, or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was measured from surface coverage (SC) of membranes (right). SM-Ppap2bΔ SMC were infected with lentivirus expressing mouse (m) or human (h) LPP3 or a catalytically inactive variant of the enzyme prior to performing migration assays (left). (C) Cells were incubated with the indicated inhibitors during the migration assay. Results are presented as mean ± SD from 3 independent cultures of SMC of each genotype. #P < 0.001 by t-test versus Ppap2bfl/fl cells with similar treatment. *P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

To exclude the possibility that the results obtained in the SM-Ppap2bΔ cells were due to developmental abnormalities that altered SMC phenotype, engineered short, hairpin RNAs were used to target Ppap2b expression and thereby reduce LPP3 expression in wild-type SMC (Supplemental Figure 4A). Decreased LPP3 expression with this approach significantly increased LPA-stimulated ERK activity 1.7-fold (P<0.001; Supplemental Figure 4B), and Rho activation 1.8-fold (P<0.001; Supplemental Figure 4C). Together, these results indicate that lowering LPP3 expression enhances the proliferation and migration of SMC, particularly under conditions where LPA is exogenously supplied, or when LPA is present in the serum component of the culture medium.

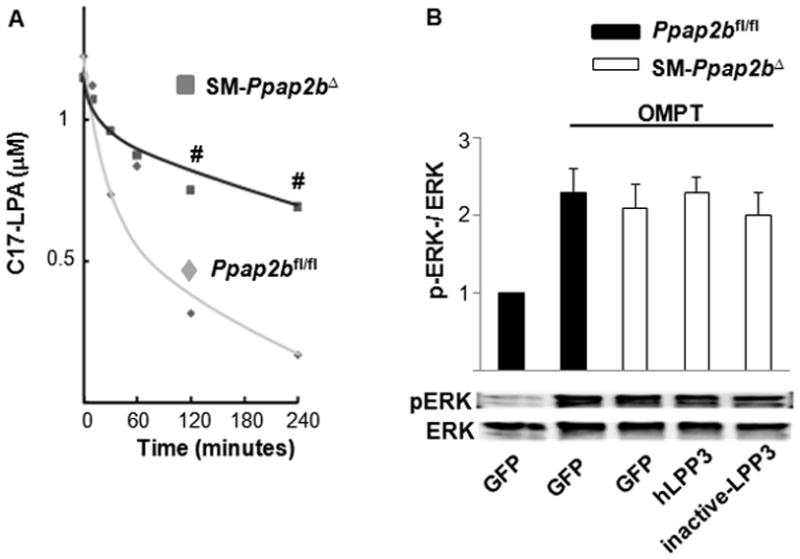

Direct measurements of intact cell LPA phosphatase activity demonstrated that exogenously applied LPA was degraded 3-fold more slowly by SM-Ppap2bΔ than control cells (Figure 4A). If the enhanced LPA-signaling of LPP3-deficient cells was due to a reduction in LPA degradation, then the SM-Ppap2bΔ cells should respond normally to a poorly hydrolyzable receptor-active LPA mimetic, such as the ester-linked thiophosphate derivative (1-oleoyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycerophosphothionate, OMPT). In support of this idea, we found that OMPT-stimulated ERK activation responses of Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ cells were similar (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Effects of LPP3 on SMC response to LPA involve LPA hydrolysis.

(A) C17-LPA was added at time 0 and the concentration in the media at various times thereafter was monitored by LC/MS/MS. (B) ERK activation was measured in Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ SMC 10 min after treatment with 2.5μM of the non-hydrolyzable LPA analog OMPT. Results are presented as the ration of pERK to total ERK. Where indicated, cells were infected with lentivirus expressing human (h) LPP3 or a catalytically inactive LPP3 variant. Results are presented as mean ± SD from 3 independent cultures of SMC of each genotype. #P < 0.001 by t-test versus Ppap2bfl/fl cells with similar treatment. No statistical difference in pERK activation was observed in the different cells following OMPT treatment.

Having established that LPP3 downregulates SMC responses to LPA, we next investigated whether the enzyme regulates SMC responses to S1P. In a proliferation assay, expression of murine LPP3, but not a catalytically inactive LPP3 mutant, reduced SMC proliferation elicited by S1P (Supplemental Figure 5A–B). In keeping with this observation, SM-Ppap2bΔ cells displayed exaggerated responses to S1P (Supplemental Figure 5C) but not PDGF (Supplemental Figure 5D). Together these results indicate that LPP3 modulates SMC responses to the lysophospholipid mediators, LPA and S1P, likely by hydrolyzing and thereby inactivating their signaling capabilities.

Consequences of genetic deletion of SMC LPP3

Our in vitro analysis of LPP3 function in SMC is consistent with a model in which LPP3 attenuates lysophospholipid-triggered signaling responses. We and others have reported that LPA and S1P contribute to the development of intimal hyperplasia by stimulating SMC migration and vascular inflammation4, 5, 21. Therefore, upregulation of LPP3 expression following vascular injury could serve as an intrinsic mechanism to limit neointimal formation. To investigate this possibility, we examined injury responses in the Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice.

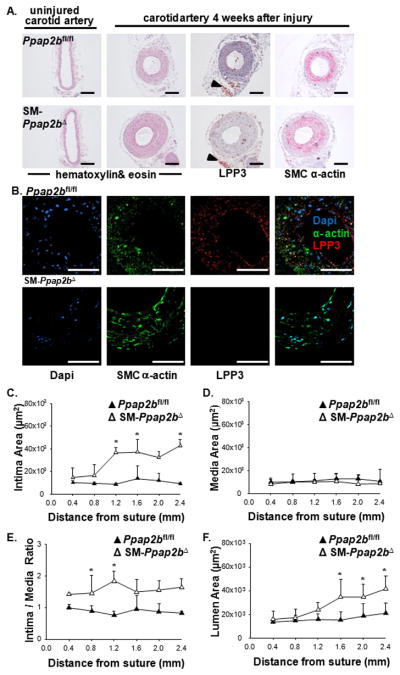

Consistent with SMC serving as a major source of vessel-associated LPP3, SM-Ppap2bΔ mice displayed attenuated upregulation of LPP3 following carotid ligation injury (Figure 5A). LPP3 expression in advential adipose cells was not affected by SM22-Cre expression (Figure 5A arrowheads). Dual staining for SMC α-actin and LPP3 indicated co-localization in Ppap2bfl/fl vessels after injury, and this co-localization was lacking in SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (Figure 5B). In the absence of SMC-LPP3, a more extensive neointimal layer formed along the length of the carotid arteries at four weeks after injury, as compared to control mice (Figure 5A and C). Intima area (Figure 5C), intima/media ratio (Figure 5E), and lumen area (Figure 5F), (but not medial area, Figure 5D), were all significantly greater in injured SM-Ppap2bΔ arteries. The findings probably do not reflect subtle differences in genetic background because no differences were observed in injury responses between Ppap2bfl/fl, SM22-Cre, and C57BL/6 mice (Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 5. LPP3 expressed following vascular injury contributes to the development of intimal hyperplasia.

(A) Representative sections of uninjured or carotid arteries from Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice 4 weeks after surgery taken ≈ 1.2mm from the site of ligation. Sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin or with antibodies to LPP3 and SM-α-actin. Arrowheads point to preserved adventitial LPP3 staining in the SMC knock-out vessel. Bar denotes 50μm. (B) Representative confocal sections of carotid arteries 4 weeks after surgery taken ≈ 1.2mm from the site of ligation in Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice. Sections were immunostained with antibodies to LPP3 (red) and SM-α-actin (green) and counterstained with DAPI. Bar denotes 100μm. Intimal area (C), medial area (D), intima/media ratio (E), and luminal area (F) along the length of vessels from Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (n = 14) at four weeks after injury presented as mean ± SD in μm2. *P <0.05 by one-way ANOVA.

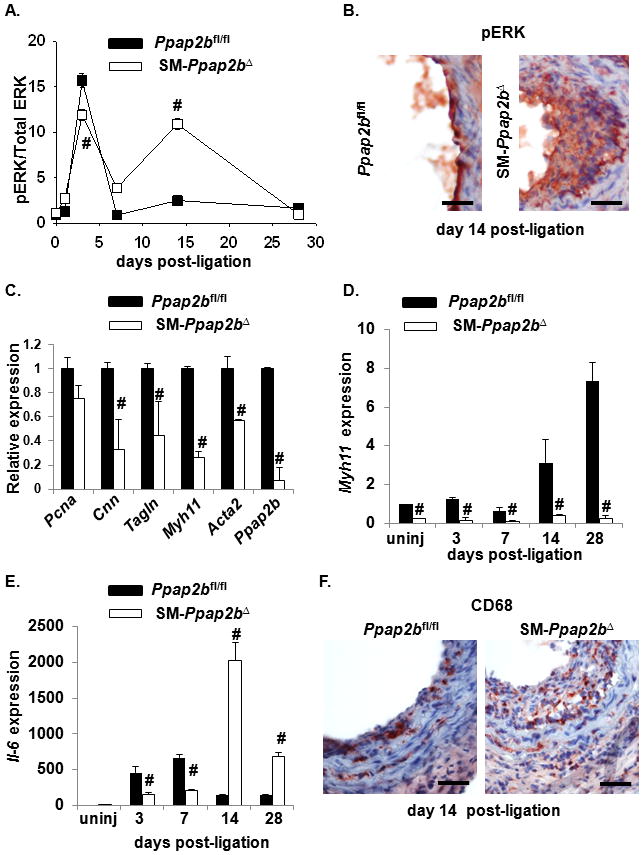

To determine the molecular underpinnings of the enhanced injury response, we examined the consequences of LPP3 deficiency in more detail. Following injury, ERK-activation in arterial tissue, as measured by the ratio of phospho-ERK to total ERK, increased and returned to baseline levels by seven days in Ppap2bfl/fl mice. Vessels from the SM-Ppap2bΔ mice demonstrated a biphasic pattern of ERK activation with persistent elevation at day 14 (Figure 6A and B and Supplemental Figure 7A). Phospho-histone H3 staining was also enhanced in injured vessels from SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (Supplemental Figure 7B). The stereotypic injury response involves dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of SMC, which can be monitored by an initial decrease followed by a later increase in SMC differentiation markers in the vessel wall. In uninjured SM-Ppap2bΔ vessels, mRNA levels for the SMC differentiation markers, Acta2 (SM-actin), Tagln (SM22), Myh11 (SM-myosin heavy chain) and Cnn (calponin) were ≈ 1.8, 2.3, 3.9 and 3.0-fold lower than levels observed in Ppap2bfl/fl arteries and, as expected, Ppap2b (LPP3) mRNA was dramatically reduced (Figure 6C). Dedifferentiation, as documented by a decline in Myh11 expression, occurred in both Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice at seven days after injury. However, the normal re-expression of Myh11 after 14 days was substantially blunted in SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (Figure 6D). Moreover, pronounced Il6 (interleukin-6) expression (Figure 6E) and vascular inflammation (Figure 6F and Supplemental Figure 7C) occurred in SM-Ppap2bΔ mice ≥ 14 days following vessel injury. No differences in LPA receptor mRNA levels were observed in aortas from SM-Ppap2bΔ and Ppap2bfl/fl mice (data not shown). Together, these observations demonstrate a role for SMC LPP3 in attenuating proliferative and inflammatory responses following vascular injury.

Figure 6. LPP3 attenuates SMC proliferation and inflammation following vascular injury.

(A) ERK activity was measured at the indicated times following arterial injury by measuring phospho-ERK (pERK) and total ERK in vessels isolated from Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice. Results are presented as the ratio of pERK/total ERK (mean ± SD) with the value observed in uninjured vessels set as 1. (B) Representative sections of carotid arteries from Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice two weeks after surgery. Sections were stained with antibodies to phosphoERK. Bar denotes 25μm (C) qPCR was used to measure expression of the SMC differentiation markers Cnn (calponin), Tagln (SM22), Myh11 (SM-myosin heavy chain), Acta2 (SM-actin), and Ppap2b (LPP3) in uninjured vessels from Ppap2bfl/fl (closed bars) and SM-Ppap2bΔ (open bars) mice. Myh11 mRNA levels (D) and Il-6 mRNA expression (E) was measured at the indicated times after injury.18s was used as an internal control. (F) Representative sections of carotid arteries from Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice two weeks after surgery. Sections were stained with antibodies to CD68. Bar denotes 25μm. Values are presented as fold increase (mean ± SD) over uninjured control from 3 separate experiments. # P<0.001 by t-test versus value at corresponding time point in control mice.

Blood pressure was similar in Ppap2bfl/fl and SM-Ppap2bΔ mice, although heart rates were significantly higher in SM-Ppap2bΔ mice (P<0.001; Supplemental Table 1). The higher heart rates may reflect lower LPP3 expression in hearts (Supplemental Figure 8) due to SM22-mediated Cre recombination in cardiac tissue, which has been observed in other studies involving the SM22-Cre transgene 37.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that LPP3 is robustly expressed in SMC following arterial injury. After ligation injury, a substantial portion of LPP3 expression appears to occur in SMC with a time course consistent with a role in influencing vascular injury responses. Genetic evidence indicates that LPP3 negatively regulates SMC phenotypic modulation both in vitro and in vivo. Loss of LPP3 in SMC enhances intimal hyperplasia, prolongs SMC dedifferentiation, and promotes vascular inflammation after arterial injury. Studies in isolated cells support a model in which a function of LPP3 is to attenuate localized production or availability of bioactive lipid mediators. Specifically, overexpression of LPP3 reduces SMC migration and proliferation in response to LPA or S1P, whereas attenuation or elimination of LPP3 amplifies SMC responses to LPA. Taken together our observations suggest that LPP3 expression after vascular injury normally limits cellular responses to LPA and/or S1P and that reduced expression of LPP3 enhances SMC phenotypic modulation and vascular inflammation, likely in part by increasing their signaling. While lack of LPP3 clearly impairs LPA degradation and inactivation, additional non-LPA dependent mechanisms of LPP3 action could also affect SMC phenotypic modulation. For example, LPP3 may have non-enzymatic functions mediated by integrin binding or catenin signaling 27, 38, 39.

A role for LPP3 in human vascular disease was suggested by the recent demonstration that an intronic, common SNP variant in PPAP2B, rs17114036, strongly associates with atherosclerotic CAD, independent of traditional risk factors such as total- HDL and LDL cholesterol, diabetes, BMI, hypertension, or smoking. In this study, we offer support for a possible mechanistic link between this new CAD locus, LPP3 expression, and vascular disease. Our findings support a model in which genetic variants associated with lower LPP3 expression would be associated with exacerbated vascular injury responses.

Emerging evidence supports a role for lysophopsholipid mediators in regulation of vascular development and function. Our data add to the weight of the evidence that LPP3 regulates vascular cell function. Our findings provide functional evidence for a novel role for LPP3 and lipid signaling in adult vascular cells If the enhanced inflammation and neointimal formation that observe in mice lacking LPP3 in SMC reflects processes that occur in the development of atherosclerosis in humans, then our results may provide a mechanism by which alterations in LPP levels (or activity) could alter risk for CAD and MI in humans.

Heart, particularly atrial tissue, robustly expresses LPP3. SM22-Cre mediated deletion of the floxed Ppap2b allele lowers LPP3 levels in heart, presumably due to recombination in cardiac tissue. This is associated with lower heart rates, which may indicate a role for LPP3 in regulating heart rate and/or function. Infusion of LPA in rabbits increases ventricular arrhythmia and the proportion of non-phosphorylated connexin43, which may inhibit junction transmission40. Whether LPP3 regulates any of these responses is not known.

In summary, LPP3 expression in arterial tissue, and in SMC in particular, increases following arterial injury. Enhanced LPP3 expression attenuates SMC proliferatory and migratory responses, and may attenuate vascular inflammation. Mice lacking SMC-LPP display enhanced vascular inflammatory responses and development of intimal hyperplasia after injury. We propose that these observations reflect a role for LPP3 in attenuating local signaling by lysophospholipid mediators. Our observations may suggest novel strategies to attenuate vascular inflammation and suggest that a better understanding of genetic factors and environmental stimuli that alter LPP3 levels is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank University of Kentucky laboratory assistants Kelsey Johnson, for animal husbandry, and Adrienne Nguyen, for assistance with histology.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by grants HL078663, HL0870166 and HL074219 from the NIH (SSS); GM050388 and 1P20RR021954 (AJM), a Beginning Grant-in-Aid (0950118G), and scientist development grant (10SDG4190036), from the American Heart Association; and UL1RR033173 from NIH NCRR (MP), a predoctoral fellowship grant from the American Heart Association (AKS) and NIH T32HL072743 (PM). A portion of this work was presented in Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology early career investigator award form at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in 2011. This material is the result of work supported with the resources and use of the facilities at the Lexington, KY VA Medical Center.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Damirin A, Tomura H, Komachi M, Liu JP, Mogi C, Tobo M, Wang JQ, Kimura T, Kuwabara A, Yamazaki Y, Ohta H, Im DS, Sato K, Okajima F. Role of lipoprotein-associated lysophospholipids in migratory activity of coronary artery smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology. 2007;292:H2513–2522. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00865.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaneyuki U, Ueda S, Yamagishi S, Kato S, Fujimura T, Shibata R, Hayashida A, Yoshimura J, Kojiro M, Oshima K, Okuda S. Pitavastatin inhibits lysophosphatidic acid-induced proliferation and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic smooth muscle cells by suppressing rac-1-mediated reactive oxygen species generation. Vascular pharmacology. 2007;46:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi K, Takahashi M, Nishida W, Yoshida K, Ohkawa Y, Kitabatake A, Aoki J, Arai H, Sobue K. Phenotypic modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells induced by unsaturated lysophosphatidic acids. Circ Res. 2001;89:251–258. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang C, Baker DL, Yasuda S, Makarova N, Balazs L, Johnson LR, Marathe GK, McIntyre TM, Xu Y, Prestwich GD, Byun HS, Bittman R, Tigyi G. Lysophosphatidic acid induces neointima formation through ppargamma activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:763–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida K, Nishida W, Hayashi K, Ohkawa Y, Ogawa A, Aoki J, Arai H, Sobue K. Vascular remodeling induced by naturally occurring unsaturated lysophosphatidic acid in vivo. Circulation. 2003;108:1746–1752. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089374.35455.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shano S, Moriyama R, Chun J, Fukushima N. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates astrocyte proliferation through lpa(1) Neurochemistry international. 2008;52:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer Zu Heringdorf D, Jakobs KH. Lysophospholipid receptors: Signalling, pharmacology and regulation by lysophospholipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:923–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khurana S, Tomar A, George SP, Wang Y, Siddiqui MR, Guo H, Tigyi G, Mathew S. Autotaxin and lysophosphatidic acid stimulate intestinal cell motility by redistribution of the actin modifying protein villin to the developing lamellipodia. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MJ, Jeon ES, Lee JS, Cho M, Suh DS, Chang CL, Kim JH. Lysophosphatidic acid in malignant ascites stimulates migration of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:499–510. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirakawa M, Karashima Y, Watanabe M, Kimura C, Ito Y, Oike M. Protein kinase a inhibits lysophosphatidic acid-induced migration of airway smooth muscle cells. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2007;321:1102–1108. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz U, Thommes K, Beier I, Vetter H. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates p21-activated kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;291:687–691. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CW, Rivera R, Dubin AE, Chun J. Lpa(4)/gpr23 is a lysophosphatidic acid (lpa) receptor utilizing g(s)-, g(q)/g(i)-mediated calcium signaling and g(12/13)-mediated rho activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:4310–4317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee HJ, Nam JS, Sun Y, Kim MJ, Choi HK, Han DH, Kim NH, Huh SO. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates camp accumulation and camp response element-binding protein phosphorylation in immortalized hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuroreport. 2006;17:523–526. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000209011.16718.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boguslawski G, Grogg JR, Welch Z, Ciechanowicz S, Sliva D, Kovala AT, McGlynn P, Brindley DN, Rhoades RA, English D. Migration of vascular smooth muscle cells induced by sphingosine 1-phosphate and related lipids: Potential role in the angiogenic response. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:264–274. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seewald S, Schmitz U, Seul C, Ko Y, Sachinidis A, Vetter H. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates protein kinase c isoforms alpha, beta, epsilon, and zeta in a pertussis toxin sensitive pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:532–537. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui MZ, Zhao G, Winokur AL, Laag E, Bydash JR, Penn MS, Chisolm GM, Xu X. Lysophosphatidic acid induction of tissue factor expression in aortic smooth muscle cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2003;23:224–230. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000054660.61191.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu YJ, Saini HK, Cheema SK, Dhalla NS. Mechanisms of lysophosphatidic acid-induced increase in intracellular calcium in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell calcium. 2005;38:569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugimoto N, Takuwa N, Okamoto H, Sakurada S, Takuwa Y. Inhibitory and stimulatory regulation of rac and cell motility by the g12/13-rho and gi pathways integrated downstream of a single g protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor isoform. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1534–1545. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1534-1545.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren H, Panchatcharam M, Mueller P, Escalante-Alcalde D, Morris AJ, Smyth SS. Lipid phosphate phosphatase (lpp3) and vascular development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.07.012. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Y, Makarova N, Tsukahara R, Guo H, Shuyu E, Farrar P, Balazs L, Zhang C, Tigyi G. Lysophosphatidic acid-induced arterial wall remodeling: Requirement of ppargamma but not lpa1 or lpa2 gpcr. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1874–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panchatcharam M, Miriyala S, Yang F, Rojas M, End C, Vallant C, Dong A, Lynch K, Chun J, Morris AJ, Smyth SS. Lysophosphatidic acid receptors 1 and 2 play roles in regulation of vascular injury responses but not blood pressure. Circ Res. 2008;103:662–670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.180778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian P, Karshovska E, Reinhard P, Megens RT, Zhou Z, Akhtar S, Schumann U, Li X, van Zandvoort M, Ludin C, Weber C, Schober A. Lysophosphatidic acid receptors lpa1 and lpa3 promote cxcl12-mediated smooth muscle progenitor cell recruitment in neointima formation. Circ Res. 2010;107:96–105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida T, Sinha S, Dandre F, Wamhoff BR, Hoofnagle MH, Kremer BE, Wang DZ, Olson EN, Owens GK. Myocardin is a key regulator of carg-dependent transcription of multiple smooth muscle marker genes. Circ Res. 2003;92:856–864. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000068405.49081.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu T, Nakazawa T, Cho A, Dastvan F, Shilling D, Daum G, Reidy MA. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 2 negatively regulates neointimal formation in mouse arteries. Circ Res. 2007;101:995–1000. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimizu T, De Wispelaere A, Winkler M, D’Souza T, Caylor J, Chen L, Dastvan F, Deou J, Cho A, Larena-Avellaneda A, Reidy M, Daum G. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 promotes neointimal hyperplasia in mouse iliac-femoral arteries. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:955–961. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Z, Subramanian P, Sevilmis G, Globke B, Soehnlein O, Karshovska E, Megens R, Heyll K, Chun J, Saulnier-Blache JS, Reinholz M, van Zandvoort M, Weber C, Schober A. Lipoprotein-derived lysophosphatidic acid promotes atherosclerosis by releasing cxcl1 from the endothelium. Cell Metab. 2011;13:592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escalante-Alcalde D, Hernandez L, Le Stunff H, Maeda R, Lee HS, Jr, Gang C, Sciorra VA, Daar I, Spiegel S, Morris AJ, Stewart CL. The lipid phosphatase lpp3 regulates extra-embryonic vasculogenesis and axis patterning. Development. 2003;130:4623–4637. doi: 10.1242/dev.00635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Escalante-Alcalde D, Morales SL, Stewart CL. Generation of a reporter-null allele of ppap2b/lpp3and its expression during embryogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:139–147. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082745de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humtsoe JO, Feng S, Thakker GD, Yang J, Hong J, Wary KK. Regulation of cell-cell interactions by phosphatidic acid phosphatase 2b/vcip. EMBO J. 2003;22:1539–1554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humtsoe JO, Bowling RA, Jr, Feng S, Wary KK. Murine lipid phosphate phosphohydrolase-3 acts as a cell-associated integrin ligand. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:906–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, Holm H, Preuss M, Stewart AF, Barbalic M, Gieger C, Absher D, Aherrahrou Z, Allayee H, Altshuler D, Anand SS, Andersen K, Anderson JL, Ardissino D, Ball SG, Balmforth AJ, Barnes TA, Becker DM, Becker LC, Berger K, Bis JC, Boekholdt SM, Boerwinkle E, Braund PS, Brown MJ, Burnett MS, Buysschaert I, Carlquist JF, Chen L, Cichon S, Codd V, Davies RW, Dedoussis G, Dehghan A, Demissie S, Devaney JM, Diemert P, Do R, Doering A, Eifert S, Mokhtari NE, Ellis SG, Elosua R, Engert JC, Epstein SE, de Faire U, Fischer M, Folsom AR, Freyer J, Gigante B, Girelli D, Gretarsdottir S, Gudnason V, Gulcher JR, Halperin E, Hammond N, Hazen SL, Hofman A, Horne BD, Illig T, Iribarren C, Jones GT, Jukema JW, Kaiser MA, Kaplan LM, Kastelein JJ, Khaw KT, Knowles JW, Kolovou G, Kong A, Laaksonen R, Lambrechts D, Leander K, Lettre G, Li M, Lieb W, Loley C, Lotery AJ, Mannucci PM, Maouche S, Martinelli N, McKeown PP, Meisinger C, Meitinger T, Melander O, Merlini PA, Mooser V, Morgan T, Muhleisen TW, Muhlestein JB, Munzel T, Musunuru K, Nahrstaedt J, Nelson CP, Nothen MM, Olivieri O, Patel RS, Patterson CC, Peters A, Peyvandi F, Qu L, Quyyumi AA, Rader DJ, Rallidis LS, Rice C, Rosendaal FR, Rubin D, Salomaa V, Sampietro ML, Sandhu MS, Schadt E, Schafer A, Schillert A, Schreiber S, Schrezenmeir J, Schwartz SM, Siscovick DS, Sivananthan M, Sivapalaratnam S, Smith A, Smith TB, Snoep JD, Soranzo N, Spertus JA, Stark K, Stirrups K, Stoll M, Tang WH, Tennstedt S, Thorgeirsson G, Thorleifsson G, Tomaszewski M, Uitterlinden AG, van Rij AM, Voight BF, Wareham NJ, Wells GA, Wichmann HE, Wild PS, Willenborg C, Witteman JC, Wright BJ, Ye S, Zeller T, Ziegler A, Cambien F, Goodall AH, Cupples LA, Quertermous T, Marz W, Hengstenberg C, Blankenberg S, Ouwehand WH, Hall AS, Deloukas P, Thompson JR, Stefansson K, Roberts R, Thorsteinsdottir U, O’Donnell CJ, McPherson R, Erdmann J, Samani NJ. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escalante-Alcalde D, Sanchez-Sanchez R, Stewart CL. Generation of a conditional ppap2b/lpp3 null allele. Genesis. 2007;45:465–469. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Juárez A, Morales-Lázaro S, Sánchez-Sánchez R, Sunkara M, Lomelí H, Velasco I, Morris AJ, Escalante-Alcalde D. Expression of lpp3 in bergmann glia is required for proper cerebellar sphingosine-1-phosphate metabolism/signaling and development. Glia. 2011;59:577–589. doi: 10.1002/glia.21126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian V, Golledge J, Ijaz T, Bruemmer D, Daugherty A. Pioglitazone-induced reductions in atherosclerosis occur via smooth muscle cell-specific interaction with ppar{gamma} Circ Res. 2010;107:953–958. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers DL, Liaw L. Improved analysis of the vascular response to arterial ligation using a multivariate approach. The American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164:43–48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A, Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1997;17:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Min Lu M, Mericko PA, Morrisey EE, Parmacek MS. High-efficiency somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes in sm22alpha-cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 2005;41:179–184. doi: 10.1002/gene.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee I, Humtsoe JO, Kohler EE, Sorio C, Wary KK. Lipid phosphate phosphatase-3 regulates tumor growth via beta-catenin and cyclin-d1 signaling. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humtsoe JO, Liu M, Malik AB, Wary KK. Lipid phosphate phosphatase 3 stabilization of beta-catenin induces endothelial cell migration and formation of branching point structures. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1593–1606. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00038-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Q, Wang TJ, Zhang CT, Ruan L, Li LD, Xu RD, Quan XQ, Ni MK. Effect of antiarrhythmic peptide on ventricular arrhythmia induced by lysophosphatidic acid. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi. 2011;39:301–304. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.