Abstract

Purpose of the research

Little is known about the relationships between pain, anxiety, and depression in women prior to breast cancer surgery. The purpose of this study was to evaluate for differences in anxiety, depression, and quality of life (QOL) in women who did and did not report the occurrence of breast pain prior to breast cancer surgery. We hypothesized that women with pain would report higher levels of anxiety and depression as well as poorer QOL than women without pain.

Methods and sample

A total of 390 women completed self-report measures of pain, anxiety depression, and QOL prior to surgery.

Key Results

Women with preoperative breast pain (28%) were significantly younger, had a lower functional status score, were more likely to be Non-white and to have gone through menopause. Over 37% of the sample reported clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms. Almost 70% of the sample reported clinically meaningful levels of anxiety. Patients with preoperative breast pain reported significantly higher depression scores and significantly lower physical well-being scores. No between group differences were found for patients' ratings of state and trait anxiety or total QOL scores.

Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that, regardless of pain status, anxiety and depression are common problems in women prior to breast cancer surgery.

Keywords: breast pain, breast cancer surgery, anxiety, depression, quality of life, psychological distress

INTRODUCTION

Almost all of the 226,870 women diagnosed with breast cancer in 2012 will undergo surgery (Siegel et al., 2012). While clinical experience suggests that the threat of a cancer diagnosis combined with the uncertainty associated with surgical and adjuvant treatments results in a significant amount of preoperative anxiety and depression, only six studies were identified that used symptom specific scales to evaluate anxiety and depression in women prior to breast cancer surgery (Hanson Frost et al., 2000; Katz et al., 2005; Millar et al., 1995; Ozalp et al., 2003; Parker et al., 2007; Vahdaninia et al., 2010). The most frequently used measures across these studies were the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S, STAI-T)(Spielberger et al., 1983), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Snaith, 2003), the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck and Steer, 1987), and the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Across these studies, approximately 34% to 53% of patients were categorized as having clinically meaningful levels of anxiety (Millar et al., 1995; Ozalp et al., 2003; Parker et al., 2007; Ramirez et al., 1995) and 18% to 26% had clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms (Parker et al., 2007; Vahdaninia et al., 2010). Taken together, findings from this limited number of studies suggest that anxiety and depression are highly prevalent in women prior to breast cancer surgery. The varying prevalence rates may be attributed to differences in the measures used to assess anxiety and depression. In addition, many of these studies had relatively small samples sizes.

Even more limited are the number of studies that evaluated for both psychological distress and the presence of pain in women prior to breast cancer surgery. In one study that used valid methods to assess both psychological distress and the occurrence of pain prior to surgery (Katz et al., 2005), 27.1% of the women reported preoperative breast pain. Compared to pain free patients, women with clinically meaningful levels of acute pain two days after surgery reported higher levels of anxiety and depression. Because recent work from our research team found that 28% of women had pain in their breast prior to breast cancer surgery (McCann et al., In press) and research on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the preoperative period are limited, we decided to examine the relationships between preoperative breast pain, anxiety, depression, QOL in a large sample of breast cancer patients (n=398) prior to surgery. We hypothesized that women with pain would report higher levels of anxiety and depression as well as poorer QOL than women without pain.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

This descriptive, correlational study is part of a larger study that evaluated for neuropathic pain and lymphedema in women who underwent breast cancer surgery. Patients were recruited from Breast Care Centers located in a Comprehensive Cancer Center, two public hospitals, and four community practices.

Patients were eligible to participate if they were: an adult woman (≥18 years) who would undergo breast cancer surgery on one breast; were able to read, write, and understand English; agreed to participate, and gave written informed consent. Patients were excluded if they were having breast cancer surgery on both breasts and/or had distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis. A total of 516 patients were approached and 410 enrolled in the study (response rate 79.4%). The major reasons for refusal were: too busy, overwhelmed with the cancer diagnosis, or insufficient time available to do baseline assessment prior to surgery.

Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Boards at each of the study sites. During the patient's preoperative visit, a clinician explained the study and determined the patient's willingness to participate. Patients were introduced to a research nurse who determined eligibility and obtained written informed consent prior to surgery. After obtaining written informed consent, patients completed the baseline study questionnaires, and height and weight were obtained. Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information.

Instruments

The demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, marital status, education, ethnicity, employment status, and income. Patient's functional status was assessed using a self-administered KPS scale which ranges from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal, I have no complaints or symptoms). The KPS has well established validity and reliability (Karnofsky, 1977; Karnofsky et al., 1948).

The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) is a short and easily understood instrument that was developed to measure comorbidity in clinical and health service research settings (Sangha et al., 2003). The questionnaire consists of 13 common medical conditions that were simplified into language that could be understood without any prior medical knowledge. Patients were asked to indicate if they had the condition using a “yes/no” format. If they indicated that they had a condition, they were asked if they received treatment for it (yes/no; proxy for disease severity) and did it limit their activities (yes/no; indication of functional limitations). Patients were given the option to add two additional conditions not listed on the instrument. For each condition, a patient can receive a maximum of 3 points. Because there are 13 defined medical conditions and 2 optional conditions, the maximum score totals 45 points if the open-ended items are used and 39 points if only the closed-ended items are used. The SCQ has well-established validity and reliability and has been used in studies of patients with a variety of chronic conditions (Brunner et al., 2008; Cieza et al., 2006; MacLean et al., 2006; Sangha et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2009).

Patients were asked to indicate if they had pain in the breast. If they responded in the affirmative they were asked to rate the intensity of their pain (i.e., average and worst pain) using 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain) numeric rating scales (NRS). Numeric rating scales are valid and reliable measures of pain intensity (Jensen, 2003). In addition, patients were asked to report the number of hours per day and the number of days per week that they experienced significant pain (i.e., pain that interfered with their ability to function).

The CES-D scale consists of 20 items selected to represent the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression. Scores can range from 0 to 60, with scores of ≥16 indicating the need for individuals to seek clinical evaluation for major depression. The CES-D has well established concurrent and construct validity (Carpenter et al., 1998; Radloff, 1977; Sheehan et al., 1995). In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha for the CES-D was 0.90.

Confirmatory factor analysis, identified four factors that are used as independent subscales: Depressed Affect (DA), Positive Affect (PA), Somatic and Retarded Activity (S), and Interpersonal Difficulties (ID) (Radloff, 1977). Subsequent studies replicated the four factor structure of the CES-D (Devins et al., 1988; Hertzog et al., 1990). In the current study, Cronbach's alphas for the CES-D subscales were 0.75 (DA), 0.86 (PA), 0.75 (S), and 0.81 (ID).

The STAI-T and STAI-S consist of 20 items each that are rated from 1 to 4. The scores for each scale are summed and can range from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates greater anxiety. The STAI-T measures an individual's predisposition to anxiety determined by his/her personality and estimates how a person generally feels. The STAI-S measures an individual's transitory emotional response to a stressful situation. It evaluates the emotional responses of worry, nervousness, tension, and feelings of apprehension related to how a person feels “right now” in a stressful situation. Cuttoff scores of ≥31.8 and ≥32.2 indicate high levels of trait and state anxiety, respectively (Spielberger et al., 1983). The STAI-S and STAI-T inventories have well-established validity and reliability (Bieling et al., 1998; Kennedy et al., 2001; Spielberger et al., 1983). In the current study, the Cronbach's alphas for the STAI-T and STAI-S were .88 and .95, respectively.

The Quality of Life-Patient Version (QOL-PV) is a 41-item instrument that measures four dimensions of QOL in cancer patients (i.e., physical well-being, psychological well-being, spiritual well-being, social well being) as well as a total QOL score. Each item is rated on a 0 to 10 NRS with higher scores indicating a better QOL. The QOL-PV has established validity and reliability (Ferrell, 1995; Ferrell et al., 1995; Padilla et al., 1990; Padilla et al., 1983). In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha for the QOL-PV total score was .86 and for the physical-, psychological-, social-, and spiritual well-being subscales the coefficients were 0.70, 0.79, 0.75, and 0.61 respectively.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Based on the women's response to the question about having pain in their breast prior to surgery, patients were categorized into the no pain (n = 280, 72%) and pain (n = 110, 28%) groups. Independent sample tests and Chi square or Fisher's Exact test analyses were used to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between women with and without pain.

In addition, separate univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to evaluate for differences in subjective reports of depression, anxiety, and QOL between women with and without pain in their breast. Based on the initial analyses of demographic and clinical characteristics, significant differences were found between women with and without pain in age, ethnicity, and menopausal status. Because previous research demonstrated that these characteristics can affect depression, anxiety, and/or QOL (Beder, 1995; Bloom et al., 2004; Ell et al., 2005; Ell et al., 2008; Gupta et al., 2006; Mosher and Danoff-Burg, 2005; Schultz et al., 2005; Shim et al., 2006; Thewes et al., 2004), age (as a continuous variable) and ethnicity and menopausal status (as dichotomous variables) were entered as covariates and presence of pain (as a dichotomous variable) was entered as a fixed factor in the univariate ANOVAs that evaluated for differences in depression, anxiety, and QOL scores between the pain groups. All calculations used actual values. Adjustments were not made for missing data or for multiple testing (Rothman, 1990). Therefore, the cohort for each analysis was dependent on the largest set of available data. A p-value of < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between Patients With and Without Breast Pain

Prior to surgery, 28% of the women (n = 110) reported pain in their breast (eight women did not answer the pain question). As shown in Table 1, except for age, KPS scores, ethnicity, income, and menopausal status, no differences were found between the two pain groups in most of the demographic and clinical characteristics. Patients who reported breast pain were significantly younger (p<.0001), more likely to be Non-white (p=.016), premenopausal (p=.01), and had a lower KPS score (p=.008).

Table 1.

- Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between Women with (n= 110) and Without (n=280) Breast Pain Prior to Breast Cancer Surgery

| Characteristic | Total Sample n = 390 | No Pain n = 280; 72% | Pain n = 110; 28% | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 54.9 (11.5) | 56.5 (11.8) | 50.9 (9.8) | t=4.81, p<0001 |

|

| ||||

| Education (years) | 15.6 (2.6) | 15.8 (2.7) | 15.4 (2.6) | t=1.42, p=.16 |

|

| ||||

| KPS score | 93.2 (10.2) | 94.0 (10.3) | 90.9 (10.1) | t=2.66, p=.008 |

|

| ||||

| SCQ score | 4.29 (2.8) | 4.32 (2.8) | 4.20 (3.1) | t=.40, p=.69 |

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 (6.1) | 27.0 (6.3) | 26.1 (5.6) | N.S. |

|

| ||||

| Number of biopsies | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.8) | U; p=.009 |

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity - % Non-white | 138 (35.6) | 89 (31.9) | 49 (45.0) | FE; p=.018 |

|

| ||||

| % Married/Partnered | 163 (42.2) | 117 (41.9) | 46 (43.0) | FE; p=.91 |

|

| ||||

| % Lives alone | 94 (24.1) | 67 (24.1) | 27 (25.2) | FE; p=.90 |

|

| ||||

| % Employed | 189 (48.8) | 134 (48.4) | 55 (50.0) | FE; p=.82 |

|

| ||||

| Annual income | ||||

| <$30,000 | 52 (16.2) | 29 (12.6) | 23 (25.3) | |

| $30,000–$99,999 | 146 (45.5) | 109 (47.4) | 37 (40.7) | U; p=.052 |

| ≥$100,000 | 123 (38.3) | 92 (40.0) | 31 (34.1) | |

|

| ||||

| AJCC Status | ||||

| Stage 0 | 64 (17.3) | 47 (17.7) | 17 (16.0) | |

| Stage I | 138 (37.2) | 105 (39.6) | 33 (31.1) | KW; p=.40 |

| Stage IIA, IIB | 135 (36.4) | 92 (34.7) | 43 (40.6) | |

| Stage IIA,IIIB,IIIC,IV | 34 (9.2) | 21 (7.9) | 13 (12.3) | |

|

| ||||

| % Postmenopausal | 243 (63.9) | 186 (67.9) | 57 (53.8) | FE; p=.012 |

|

| ||||

| % Received neoadjuvant therapy | 78 (20.1) | 59 (21.1) | 19 (17.3) | FE; p=.48 |

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMI = Body Mass Index; kg/m2 = kilograms/meter squared; KPS = Karnofsky Performance Status; KW = Kruskal-Wallis; N.S. = not significant; SCQ = Self-Administered Co-Morbidity Questionnaire

Detailed information on the pain characteristics is reported elsewhere.(McCann et al., In press) In brief, patients rated their average pain as 2.2 (±2.1) and their worst pain as 3.5 (±2.3). In addition, they reported that they experienced a significant amount of pain (i.e., pain that interfered with their function) on 2.8 (±2.7) days per week for 6.1 (±7.8) hours per day.

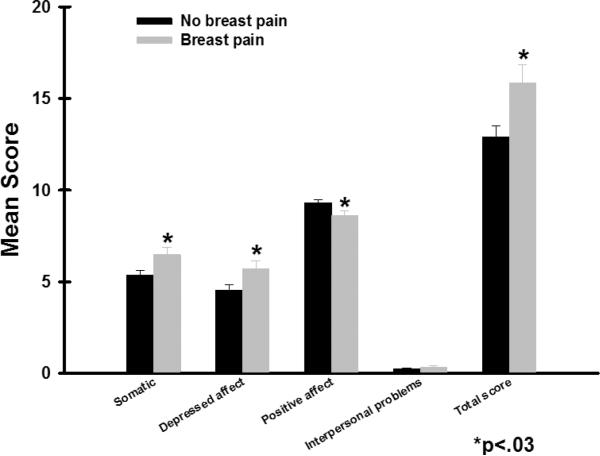

Differences in CES-D Total and Subscale Scores Between Women With and Without Breast Pain

The mean CES-D score for the total sample was 13.7 (SD=9.7) and 37.5% of the women had a CES-D score of ≥16. As shown in Figure 1, after controlling for age, ethnicity, and menopausal status, women with breast pain reported significantly higher total CES-D scores (15.8±0.9; p=.01) than women without pain (12.8±0.5; p=0.01). Women with pain reported significantly higher scores on the S subscale (6.4±0.4 versus 5.3±0.2, p=.004), DA subscale (5.6±0.4 versus 4.5±0.2, p=.002), and lower scores in the PA subscale (8.4±2.6 versus 9.3±2.6, p=.005) than women without pain.

Figure 1.

Differences in total and subscale scores on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale between women with and without pain prior to surgery. All values are plotted as means ± standard error of the mean.

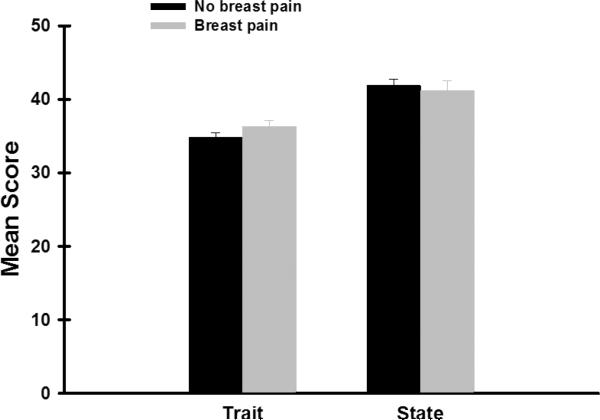

Differences in STAI-T and STAI-S scores Between Women With and Without Breast Pain

The mean STAI-T and STAI-S scales for the total sample were 35.3 (±9.0) and 41.7 (±13.5), respectively. About 59% of the women had a STAI-T score of ≥31.8 and 69% had a STAI-S score of ≥32.2. As shown in Figure 2, after controlling for age, ethnicity, and menopausal status, no differences in trait or state anxiety scores were found between the two pain groups.

Figure 2.

Differences in total and subscale scores on the Spielberger Trait and State Anxiety scale between women with and without pain prior to surgery. All values are plotted as means ± standard error of the mean.

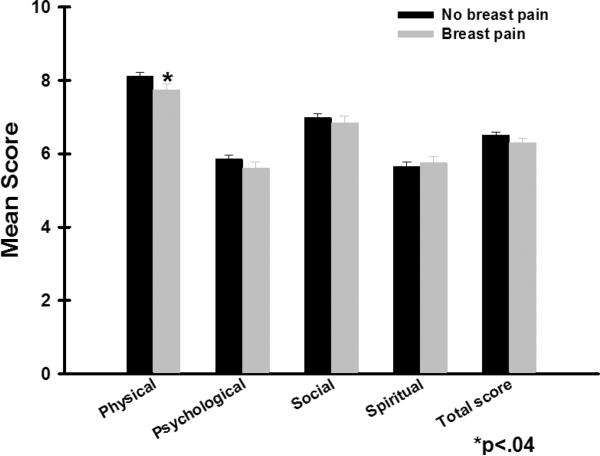

Differences in Total and Subscale QOL-PV Scores Between Women With and Without Breast Pain

As shown in Figure 3, after controlling for age, ethnicity, and menopausal status, except for the physical well-being subscale, no differences in total or subscale QOL scores were found between the two pain groups. Patients with breast pain prior to surgery reported significantly lower physical well-being scores than patients without pain (p=.04).

Figure 3.

Differences in total and subscale scores on the Quality of Life Scale-Patient Version between women with and without pain prior to surgery. All values are plotted as means ± standard error of the mean.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate for differences in depression and anxiety in a large sample of women who did and did not have pain in their breast prior to breast cancer surgery. Regardless of pain status, 37.5% of these women reported a CES-D score above the cutoff for clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms. This prevalence is higher than previous reports of depressive symptoms that ranged between 18% to 26% (Parker et al., 2007). In terms of anxiety, regardless of pain status, almost 70% of the sample reported clinically meaningful levels of anxiety. This finding is significantly higher than the 50% reported in previous studies (Ozalp et al., 2003; Parker et al., 2007). The differences in prevalence rates across studies may be related to differences in the measures used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, timing of the measures, and sample characteristics. Taken together, these findings suggest that a relatively high percentage of women are experiencing significant amounts of psychological distress prior to surgery for breast cancer. Future studies need to incorporate a clinical interview to refine the diagnoses of anxiety and depression

Our hypothesis regarding the relationship between depressive symptoms and pain was supported. After controlling for the effects of age, menopausal status, and ethnicity, women with pain reported significantly higher CES-D Total, Somatic, and Depressed Affect subscale scores and significantly lower Positive Affect subscale scores. The difference in total CES-D scores between the two pain groups represents not only a statistically significant but a clinically meaningful difference in depressive symptoms (i.e., d=1.2) (Osoba, 1999). In addition, 49.5% of the women with pain met the cutoff for clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms compared to only 32.8% in the no pain group (p=.003). Of note, in the pain group, the combination of high DA with low PA subscale scores is characteristic of the expression of a depressive disorder (Watson et al., 1988). Furthermore, when specific conditions on SCQ were evaluated, a higher percentage of women with pain reported a history of depressive illness (31%) compared to the no pain group (18%, p=.009). These women with a history of depressive illness, high depressive symptoms scores, and pain prior to surgery may represent a group of women who are at risk for worse postoperative outcomes.

Only one study was found that reported CES-D subscale scores for oncology patients (Musick et al., 1998). Compared to Musick and colleagues' large sample of cancer patients (n = 1371) with a variety of cancer diagnoses that included both women and men (DA=1.2, S=0.9, PA=2.7, ID=0.9), women in our study reported higher DA (4.9) and S (5.6) subscale scores, better PA (9.1) scores, and similar ID scores (0.3). Similar differences exist between our findings and mean subscale scores reported for a community sample of insured women (n = 218) (DA=3.3, S=4.5, PA=2.1, I.D=0.4) (Gatz and Hurwicz, 1990) and older persons (n = 174) (DA=2.0, S=3.1, PA=5.1, I.D=0.1) (Baune et al., 2007). In contrast, CES-D subscale scores for women in our study are similar for the S and PA subscales of the CES-D reported by a sample of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (n=415; DA=2.6, S=5.8, PA=9.1, I.D=0.9) where 83% of the patients were women (McQuillan et al., 2003). Interestingly, the CES-D subscale scores for our sample are lower than scores reported by a community sample (n = 680) of married women (DA=5.6, S=8.1, PA=6.3, I.D=0.7)(Ross and Mirowsky, 1984). However, this inconsistent finding might be explained by the fact that Ross and colleagues (1984) removed two items from the CES-D (“crying” and “life is a failure”) before the factor structure of the subscales was tested.

Our hypothesis regarding differences in the severity of both state and trait anxiety was not supported. While previous studies of acute and chronic pain have shown positive associations between anxiety and pain (Katz et al., 2005; Poleshuck et al., 2006), it is not entirely clear why pain status influenced depression but not anxiety. One possible explanation is that high levels of anxiety associated with the diagnosis and impending surgery in both groups blunted any differential effects of pain on this symptom.

As expected, women with pain prior to surgery scored lower on the physical well-being subscale of the QOL-PV compared to women without pain. However, the total and psychological, spiritual, and social subscale scores were not different between the two pain groups. It is not entirely clear why between group differences in psychological well-being scores were not found given the fact that these women differed on depression scores. One possible explanation is that the psychological well-being subscale of the QOL-PV evaluates additional aspects of psychological well-being that are not evaluated using either the CES-D or the STAI-S (e.g., coping) and that these characteristics are not affected by pain.

Several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, self-report measures were used to evaluate depression and anxiety. Future studies need to incorporate a diagnostic interview like the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders to confirm a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Second, based on recent reports that neuroticism is associated with depression and anxiety (Middeldorp et al., 2005), future studies should include a personality measure in order to assess the relative contribution of various aspects of an individual's personality to pain, anxiety, and depression. A possibility exists that the rates of anxiety and depression reported in this study may be underestimations because one of the major reasons for refusal was that women reported that they were too overwhelmed by their cancer experience to participate in this study. Finally, because the majority of women were Caucasian and well-educated, findings from this study may not generalize to all women who undergo surgery for breast cancer.

Findings from this study suggest that a significant percentage of women, regardless of pain status, experience anxiety and depressive symptoms. Future studies need to evaluate for changes over time in anxiety and depressive symptoms and the factors that influence the trajectories of these symptoms.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Baune BT, Suslow T, Arolt V, Berger K. The relationship between psychological dimensions of depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in the elderly - the MEMO-Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; San Antonio, Texas: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beder J. Perceived social support and adjustment to mastectomy in socioeconomically disadvantaged black women. Soc. Work Health Care. 1995;22:55–71. doi: 10.1300/j010v22n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Trait version: structure and content re-examined. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:777–788. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Chang S, Banks PJ. Then and now: quality of life of young breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:147–160. doi: 10.1002/pon.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F, Bachmann LM, Weber U, Kessels AG, Perez RS, Marinus J, Kissling R. Complex regional pain syndrome 1--the Swiss cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA, Wilson J, Hall LA, Rayens MK, Sachs B, Cunningham LL. Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19:481–494. doi: 10.1080/016128498248917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustun BT, Stucki G. Identification of candidate categories of the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) for a Generic ICF Core Set based on regression modelling. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devins GM, Orme CE, Costello CG, Binik YM. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. Psychology and Health. 1988;2:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino I, Muderspach L, Russell C. Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee PJ, Vourlekis B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer. 2008;112:616–625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR. The impact of pain on quality of life. A decade of research. Nurs Clin North Am. 1995;30:609–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatz M, Hurwicz ML. Are old people more depressed? Cross-sectional data on Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale factors. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:284–290. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Sturdee DW, Palin SL, Majumder K, Fear R, Marshall T, Paterson I. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: the prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric. 2006;9:49–58. doi: 10.1080/13697130500487224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson Frost M, Suman VJ, Rummans TA, Dose AM, Taylor M, Novotny P, Johnson R, Evans RE. Physical, psychological and social well-being of women with breast cancer: the influence of disease phase. Psychooncology. 2000;9:221–231. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<221::aid-pon456>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usula PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R. Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Sepression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP. The validity and reliability of pain measures in adults with cancer. J Pain. 2003;4:2–21. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky D. Performance scale. Plenum Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Poleshuck EL, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, Dworkin RH. Risk factors for acute pain and its persistence following breast cancer surgery. Pain. 2005;119:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q. 2001;72:263–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1010305200087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean CD, Littenberg B, Kennedy AG. Limitations of diabetes pharmacotherapy: results from the Vermont Diabetes Information System study. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann B, Miaskowski C, Koetters T, Baggott C, West C, Levine JD, Elboim C, Abrams G, Hamolsky D, Dunn L, Rugo H, Dodd M, Paul SM, Neuhaus J, Cooper B, Schmidt B, Langford DJ, Cataldo J, Aouizerat BE. Associations between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and breast pain in women prior to breast cancer surgery. J Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.02.358. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J, Fifield J, Sheehan TJ, Reisine S, Tennen H, Hesselbrock V, Rothfield N. A comparison of self-reports of distress and affective disorder diagnoses in rheumatoid arthritis: a receiver operator characteristic analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:368–376. doi: 10.1002/art.11116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp CM, Cath DC, Van Dyck R, Boomsma DI. The co-morbidity of anxiety and depression in the perspective of genetic epidemiology. A review of twin and family studies. Psychol Med. 2005;35:611–624. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400412x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar K, Jelicic M, Bonke B, Asbury AJ. Assessment of preoperative anxiety: comparison of measures in patients awaiting surgery for breast cancer. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:180–183. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Danoff-Burg S. A review of age differences in psychological adjustment to breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2005;23:101–114. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Koenig HG, Hays JC, Cohen HJ. Religious activity and depression among community-dwelling elderly persons with cancer: the moderating effect of race. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:S218–227. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D. Interpreting the meaningfulness of changes in health-related quality of life scores: lessons from studies in adults. Int. J. Cancer. Suppl. 1999;12:132–137. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<132::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozalp G, Sarioglu R, Tuncel G, Aslan K, Kadiogullari N. Preoperative emotional states in patients with breast cancer and postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:26–29. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.470105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla GV, Ferrell B, Grant MM, Rhiner M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nurs. 1990;13:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla GV, Presant C, Grant MM, Metter G, Lipsett J, Heide F. Quality of life index for patients with cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1983;6:117–126. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker PA, Youssef A, Walker S, Basen-Engquist K, Cohen L, Gritz ER, Wei QX, Robb GL. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3078–3089. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck EL, Katz J, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, Dworkin RH. Risk factors for chronic pain following breast cancer surgery: a prospective study. J Pain. 2006;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AJ, Richards MA, Jarrett SR, Fentiman IS. Can mood disorder in women with breast cancer be identified preoperatively? Br J Cancer. 1995;72:1509–1512. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Components of depressed mood in married men and women. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies' Depression Scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:997–1004. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz PN, Klein MJ, Beck ML, Stava C, Sellin RV. Breast cancer: relationship between menopausal symptoms, physiologic health effects of cancer treatment and physical constraints on quality of life in long-term survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The measurement structure of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1995;64:507–521. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim EJ, Mehnert A, Koyama A, Cho SJ, Inui H, Paik NS, Koch U. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer: A cross-cultural survey of German, Japanese, and South Korean patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:341–350. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Zebrack BJ. Health status and quality of life among non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:3312–3323. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CG, Gorsuch RL, Suchene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Anxiety (Form Y): Self Evaluation Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors; a qualitative study of the shared and unique needs of younger versus older survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13:177–189. doi: 10.1002/pon.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahdaninia M, Omidvari S, Montazeri A. What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow-up study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010;45:355–361. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:346–353. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]