Abstract

Efforts to identify, develop, refine, and test strategies to disseminate and implement evidence-based treatments have been prioritized in order to improve the quality of health and mental healthcare delivery. However, this task is complicated by an implementation science literature characterized by inconsistent language use and inadequate descriptions of implementation strategies. This article brings more depth and clarity to implementation research and practice by presenting a consolidated compilation of discrete implementation strategies, based upon a review of 205 sources published between 1995 and 2011. The resulting compilation includes 68 implementation strategies and definitions, which are grouped according to six key implementation processes: planning, educating, financing, restructuring, managing quality, and attending to the policy context. This consolidated compilation can serve as a reference to stakeholders who wish to implement clinical innovations in health and mental healthcare and can facilitate the development of multifaceted, multilevel implementation plans that are tailored to local contexts.

Keywords: implementation research, implementation strategies, evidence-based practice, health, mental health

Introduction

Internationally, there is a substantial gap between innovations in health and mental healthcare and their delivery in routine practice (Institute of Medicine, 2001, 2006; Madon, Hofman, Kupfer, & Glass, 2007). Implementation research has emerged as a promising way of bridging this “quality chasm” (Institute of Medicine, 2001) by advancing knowledge about how to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Greenhalgh, Robert, Macfarlane, Bate, & Kyriakidou, 2004; Grol, Wensing, & Eccles, 2005; Proctor, et al., 2009; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009). Implementation research has been defined as “the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices” to improve the quality of service delivery in routine care (Eccles, et al., 2009; Eccles & Mittman, 2006).

From the beginning, implementation scientists have stressed the use of specific strategies to accomplish this translational work (Lomas, 1993), and recently, the identification, development, refinement, and testing of strategies to implement evidence-based innovations has been prioritized (National Institutes of Health, 2010). In fact, the Institute of Medicine (2009) recently identified the assessment of dissemination and implementation strategies as a top-quartile priority for comparative effectiveness research. Yet, leaders in the field have identified critical challenges that inhibit the conduct of implementation research and practice. For instance, Michie and colleagues (2009) bemoan the fact that implementation strategies are rarely defined and are often poorly described. When they are described, the terminology used is inconsistent (Michie, et al., 2009). For example, multiple terms are used for implementation processes (e.g., knowledge translation, diffusion, dissemination, translation) and strategies (e.g., methods, interventions, models) resulting in a literature that McKibbon and colleagues (2010) describe as a “Tower of Babel.” These variations in terminology and description inhibit scientific replication and meta-analyses (Michie, et al., 2009) and reduce the value of the literature for stakeholders (e.g., researchers, administrators, etc.) who seek implementation guidance, making it difficult for them to identify and select strategies that have the potential to promote the implementation and sustainability of clinical innovations.

We define an implementation strategy as a systematic intervention process to adopt and integrate evidence-based health innovations into usual care. Our view of health innovations is relatively broad, and includes evidence-based treatments, practice guidelines, and empirically-supported multi-component intervention programs that focus on prevention and treatment in health and mental health. We differentiate discrete, multifaceted and blended implementation strategies. Discrete strategies are the most recognizable and commonly cited implementation actions (e.g., reminders, educational meetings) and involve one process or action. A multifaceted implementation strategy (Grimshaw, et al., 2001; Grol & Grimshaw, 2003) uses two or more discrete strategies (e.g., training plus technical assistance). We reserve the term blended strategy for instances in which a number of discrete strategies, addressing multiple levels and barriers to change, are interwoven and packaged as a protocolized or branded implementation intervention. Blended strategies are inherently multifaceted; however, all multifaceted strategies are not blended. There are several examples of such models, including the Translating Research Into Practice intervention, the Availability, Responsibility and Continuity model, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Framework for Spread (Brooks, Titler, Ardery, & Herr, 2009; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, Schoenwald, Hemmelgarn, Green, Dukes, Armstrong, & Chapman, 2010; Massoud, et al., 2006; Titler, et al., 2009).

Discrete implementation strategies can be identified and extracted from empirical evaluations of implementation efforts; descriptions of blended implementation models; review articles, compilations, and taxonomies; and a limited number of texts pertinent to implementation research and practice (Grol, et al., 2005; Straus, et al., 2009). For illustrative purposes, we provide brief summaries of 41 reviews and compilations of implementation strategies in Table 1.

Table 1.

The foci of prior compilations of implementation strategies

| Source and Date |

Focus | Discipline/Clinical Specialty |

|---|---|---|

| Bero et al., 1998 | Provides an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings |

Healthcare |

| Cabana, Rushton, & Rush, 2002 | Addresses identified barriers to the implementation of depression guidelines in primary medical care |

Medicine/Primary Care |

| Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC), 2002 | Represents interventions that can be extracted by authors conducting reviews for EPOC, and includes professional interventions, financial interventions, organizational interventions, and regulatory interventions |

Healthcare |

| Curry, 2000 | Suggests organizational interventions to increase the adoption, reach, and impact of evidence-based guidelines |

Healthcare |

| Davis & Davis, 2009 | Reviews educational interventions that can be utilized in implementation efforts in healthcare |

Healthcare |

| Eccles & Foy, 2009 | Describes strategies that facilitate implementation through social influences |

Healthcare |

| Ferlie, 2009 | Reviews organizational approaches to implementation and quality improvement |

Healthcare |

| Gilbody, Whitty, Grimshaw, & Thomas, 2003 | Focuses on educational and organizational strategies to improve the management of depression |

Medicine/Primary Care |

| Grimshaw et al., 2001 | Overviews systematic reviews of professional, educational, or quality assurance interventions to improve quality of care |

Healthcare |

| Grimshaw et al, 2004 | Systematically reviews studies of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies |

Healthcare |

| Grimshaw et al., 2006 | Systematically reviews studies of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies |

Healthcare |

| Grol, 1997 | Suggests a range of strategies with the potential to impact both internal processes and external influences that have the potential to change clinical practice |

Healthcare |

| Grol, 2001 | Includes twelve broad strategies to improve patient care based upon a review of systematic reviews |

Medicine |

| Grol, Bosch, Hulscher, Eccles, & Wensing, 2007 | Presents theories pertinent to the implementation of change in clinical practice, and provides possible strategies and interventions that are linked to theoretically derived hypotheses about change and barriers to change |

Healthcare |

| Grol & Grimshaw, 2003 | Summarizes the state of the evidence for strategies to implement evidence in healthcare |

Healthcare |

| Gupta & McKibbon, 2009 | Describes several informatics interventions that help to collect, summarize, package, and deliver information |

Healthcare |

| Hysong, Best & Pugh, 2007 | Highlights strategies used to implement clinical practice guidelines in high and low performing Veterans Affairs Medical Centers |

Healthcare |

| Katon, Zatzick, Bond, & Williams, 2006 | Reviews key dissemination efforts involving collaborative care for depression, evidence-based treatments for severe mental illness, and interventions for acutely injured trauma survivors |

Medicine/Primary Care/Mental Health |

| Leeman, Baerhnhoeldt & Sandelowsky, 2007 | Presents a theory-based taxonomy of methods for implementing change in nursing practice |

Nursing |

| Magnabosco, 2006 | Compiles innovative state level activities and strategies to implement evidence-based mental health treatments in the Evidence-Based Practices Project |

Mental Health |

| McHugh & Barlow, 2010 | Reviews exemplar efforts at the national, state, and individual treatment developer levels to implement evidence-based mental health interventions into service delivery settings |

Mental Health |

| McMaster University, 2010 | Combines Cochrane’s EPOC and Consumers and Communications review groups’ taxonomies to present a taxonomy of implementation strategies |

Healthcare |

| Medves et al, 2010 | Focuses on implementation strategies that can be used for healthcare teams and team-based practice |

Healthcare |

| Moulding, Silagy, & Weller, 1999 | Identifies strategies based upon a conceptual framework for guideline dissemination and implementation |

Healthcare |

| O’Connor, 2009 | Reviews interventions to improve patients’ knowledge, experiences, service use, health behavior, and health status |

Healthcare |

| Prior, Guerin, Grimmer-Somers, 2008 | Presents an overview of systematic reviews of guideline implementation strategies |

Healthcare |

| Rabin, Glasgow, Kerner, Klump, & Brownson, 2010 | Reviews existing dissemination and implementation studies in the areas of smoking, healthy diet, physical activity and sun protection |

Smoking, Healthy Diet, Physical Activity, Sun Protection |

| Raghavan, Bright & Shadoin, 2008 | Examines organizational-, payer and regulatory-, and political-level opportunities to develop implementation strategies to promote the use of evidence-based mental health interventions |

Mental Health Policy |

| Rx for Change, 2010 | Based upon Cochrane’s EPOC review group’s taxonomy of interventions, Rx for Change’s database provides references to implementation and quality improvement literature |

Healthcare |

| Ryan, Lowe, Santesso, & Hill, 2010 | Describes the Cochrane Consumers and Communications Review Group’s taxonomy of consumer focused interventions to increase evidence- based prescribing and medicine use |

Medicine |

| Shojania, McDonald, Wachter, & Owens, 2004 | Suggests a taxonomy of nine types of quality improvement strategies and provides specific examples of discrete strategies within each category |

Healthcare |

| Shojania et al., 2006 | Assesses the impact of 11 distinct strategies for quality improvement in adults with type 2 diabetes |

Medicine/Diabetes |

| Stone et al., 2002 | Evaluates the effectiveness of previously studied approaches for improving adherence to guidelines for adult immunization and cancer screening |

Medicine/ Oncology |

| Torrey, Finnerty, Evans, & Wyzik, 2003 | Suggests a range of potential strategies for moving evidence-based mental health interventions into routine care |

Mental Health |

| Walter, Nutley, & Davies, 2003 | Lists and defines interventions designed to increase research utilization |

Broad Focus on Research Utilization in Policy and Practice |

| Walter, Nutley, & Davies, 2005 | Presents a systematic review of the effectiveness of different mechanisms for promoting research use |

Health, Social Care, Criminal Justice, and Education |

| Wensing, Bosch & Grol, 2009 | Provides a broad overview of implementation interventions utilized in healthcare settings |

Healthcare |

| Wensing, Elwyn & Grol, 2005 | Reviews patient-mediated implementation strategies | Healthcare |

| Wensing & Grol, 2005 | Discusses educational interventions used to improve patient care |

Healthcare |

| Wensing, Klazinga, Wollerstain & Grol, 2005 | Focuses on organizational and financial strategies with the potential to change the behavior of patients and healthcare teams |

Healthcare |

Many of these source documents represent seminal contributions to the field, but none were intended to be a consolidated menu of potential implementation options for a broad range of stakeholders in health and mental healthcare, thus the strategies included in each are limited. For instance, the most influential compilation to date, the Cochrane Collaboration’s Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group’s Data Collection Checklist (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002), was created to guide systematic reviews on professional, financial, organizational, or regulatory interventions to improve healthcare practice. Thus, in addition to implementation strategies, it includes many interventions that apply to improving the quality of care more generally (e.g., case management, arrangements for follow-up, telemedicine). Other sources are purposely narrow in scope, focusing on: strategies with known evidence on effectiveness (e.g., Bero, et al., 1998; Grimshaw, et al., 2006; Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Shojania, et al., 2006); specific medical conditions, fields of practice or disciplines (e.g., Cabana, Rushton, & Rush, 2002; Gilbody, Whitty, Grimshaw, & Thomas, 2003; Stone, et al., 2002); strategies that were employed in a specific setting or study (e.g., Hysong, Best & Pugh, 2007; Magnabosco, 2006); “exemplar” programs or strategies (e.g., Katon, Zatzick, Bond, & Williams, 2006; McHugh & Barlow, 2010); one level of target such as consumers or practitioners (e.g., Ryan, Lowe, Santesso, & Hill, 2010); or one type of strategy such as educational or organizational strategies (e.g., Gilbody, Whitty, Grimshaw, & Thomas, 2003; Raghavan, Bright & Shadoin, 2008). The characteristics of some of these reviews and compilations may lead healthcare stakeholders to believe that there are relatively few strategies from which to choose. Additionally, many of these compilations do not provide definitions or provide definitions that do not adequately describe the specific actions that need to be taken by stakeholders.

New Contributions

This review follows and extends previous reviews and compilations by presenting a consolidated compilation of discrete implementation strategies. We attempt to advance clarity within the field by defining each discrete strategy and providing referenced examples. While it is impossible to develop a comprehensive compilation, we intend to improve upon existing compilations by providing a reference tool that more closely reflects the full range of implementation actions that are available to those who wish to adopt, implement, and sustain innovations in routine care.

A consolidated compilation of implementation strategies will benefit a number of healthcare stakeholders by highlighting available options and allowing them to thoughtfully plan and execute programs of implementation using multiple strategies tailored to specific settings, needs, and timetables. For example, researchers and practitioners who develop and test clinical innovations; administrators and clinical managers considering the adoption of an innovation; funders who wish to maximize their investment in clinical innovations; and healthcare consumers, their families, and advocates who desire access to effective services all stand to benefit from a consolidated menu of discrete implementation strategies.

We focus on both health and mental health, because while many strategies described in the literature are relevant to both broad fields, we have found that they both emphasize a different array of strategies and stand to be enhanced through “dialogue” with the other. Unlike reviews and compilations that focus on a narrow sector of health or mental healthcare, our aim is to develop a compilation that is essentially generic and broadly applicable, so that stakeholders could use the compilation to tailor their implementation plans depending upon the innovation being implemented and the specific barriers and facilitators of their implementation context. The strategies employed will likely differ depending upon the practice being implemented (and a myriad of contextual factors). For example, increasing the frequency of hand washing in medical settings may require different strategies (e.g. audit and feedback, reminders) than would the implementation of a complex cognitive-behavioral psychosocial treatment in a community mental health clinic (which would likely require training, supervision, consultation). Though we focus on the implementation of clinical innovations, some of the included strategies may also be useful in reducing bad practices (e.g. poor hand hygiene) and critical incidences (e.g. infections, unexpected death in heart surgery). Finally, we classify discrete strategies under taxonomic headings that highlight their usefulness vis-à-vis six broad implementation processes, though we caution against reducing these discrete strategies to their taxonomic headings.

Conceptual Model

We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to guide this review (Damschroder, et al., 2009). Starting with Greenhalgh et al.’s (2004) “Conceptual model for considering the determinants of diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of innovations in health service delivery and organization” (Greenhalgh, et al., 2004), the CFIR consolidates 19 different conceptual frameworks pertinent to implementation research and practice. In doing so, the CFIR highlights the many commonalities between different models, theories, and frameworks; and expands our conceptual understanding by ensuring that the unique contributions of each model are represented. The CFIR suggests that implementation is influenced by: 1) intervention characteristics (evidentiary support, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, and complexity), 2) the outer setting (patient needs and resources, organizational connectedness, peer pressure, external policy and incentives), 3) the inner setting (structural characteristics, networks and communications, culture, climate, readiness for implementation), the 4) characteristics of the individuals involved (knowledge, self-efficacy, stage of change, identification with organization, etc.), and 5) the process of implementation (planning, engaging, executing, reflecting, evaluating). This model informed our review process by capturing the complex, multi-level nature (Shortell, 2004) of implementation, which compelled us to consider implementation strategies in a holistic manner. The CFIR suggests that successful implementation may necessitate the use of an array of strategies that exert their effects at multiple levels of the implementation context. Indeed, each mutable aspect of the implementation context that the CFIR highlights is potentially amenable to the application of targeted and tailored implementation strategies. Though we were limited to the strategies represented in the health and mental health literature, we attempted to extract and define strategies that had the potential to impact any of the components specified in the CFIR.

Methods

Review Method

In order to identify sources that describe active efforts to implement clinical innovations in health and mental health service settings we conducted a narrative review (Dijkers, 2009). This approach was chosen due the breadth of our research question and the diffuse nature of the literature focusing on implementation strategies (McKibbon, et al., 2010). Indeed, Hamersley notes that narrative reviews are well suited for research questions that are broad and don’t necessarily benefit from a pre-determined protocol that sets forth procedures to be followed (Hammersley, 2002). Narrative reviews involve a more inductive approach (Hammersley, 2002), and are effective in capturing diversities and pluralities of understanding (Jones, 2004). Some elements of our process are more often associated with systematic reviews (Zed, Rowe, Loewen, & Abu-Laban, 2003), such as the specification of databases and search terms and querying experts to identify important references. However, we made no effort to assess or exclude sources based upon methodological quality, nor was it within our scope to evaluate the empirical evidence of the strategies we identify, lending further support to the appropriateness of a narrative approach. McPheeters and colleagues (2006) note that narrative reviews are best conducted in a team; thus, we leveraged the expertise of an implementation research workgroup.

Workgroup Composition

We formed an eight member multidisciplinary workgroup comprised of physicians and social workers/mental health services researchers with both clinical and research backgrounds in general heath, emergency medicine, mental health, and substance abuse treatment. Members of the group maintain leadership positions and associations with an NIMH-funded research center, an NIH-funded research core, and an NIMH-funded training institute, all of which focus on implementation research in health and/or mental health. Each workgroup member had experience conducting or consulting on implementation research in health or mental health settings, including the conduct of NIH R01s and other federally funded research. The workgroup also included appointed leaders in quality, safety, and evidence-based medicine at an academic medical center. Finally, nearly all members of the workgroup had experience conducing narrative or systematic reviews/meta-analyses.

Data Sources

Books, articles, reports, and websites describing implementation strategies were drawn from three sources: (1) workgroup members’ suggestions of compilations and blended models (steps one & two), (2) a database search (step three), and an expert query (step four). These steps are described in more detail below.

(1) Compilations and lists

We started by examining compilations (n = 17) that were known to members of the workgroup. We began by reviewing the EPOC Data Collection Checklist, as it is the most frequently referenced source document in reviews of implementation strategies (e.g., Chaillet, et al., 2006; Gilbody, et al., 2003; Grimshaw, et al., 2006; Grimshaw, et al., 2004; Shojania, et al., 2006; Stone, et al., 2002).

(2) Blended models

We reviewed blended implementation models (n = 12) known to our group.

(3) Database searches

A database search was conducted with the aid of an academic librarian. To target health and mental health literature, we searched for articles in English language published between 1995 and 2011 in CINAHL Plus, Global Health, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and SocINDEX using the EBSCO database host. The search strategy is described in detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Search strategy

Search string:

|

This search yielded 553 abstracts. These abstracts were reviewed, and we eliminated those that did not describe active implementation efforts (e.g., studies of diffusion), did not involve health or mental health service settings, or that were obviously unrelated to implementation. The first and second author reviewed a sample of 50 abstracts, and obtained excellent agreement (kappa = .88), after which the first author reviewed the remaining abstracts. Ultimately, this yielded 142 full-text articles to review.

(4) Expert query

Sixty-four implementation researchers were contacted and asked if they could “provide us leads toward finding existing compilations, lists or taxonomies of implementation strategies, and/or bundled or blended implementation strategies.” Our list of scholars included the editorial board of Implementation Science and the Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health Study Section of the National Institutes of Health. We received responses from 16 experts (13 from the Implementation Science editorial board and 3 from individuals that they prompted to contact us) who identified 33 additional sources.

Sources Identified

In total, 205 sources were identified (one article was identified by a reviewer of this article). This included 41 compilations, taxonomies, or reviews of multiple strategies; 15 descriptions of blended strategies; and 149 empirical, descriptive, and conceptual articles. A full list of references for all 205 sources is available from the lead author upon request.

Data Extraction Process

Two workgroup members reviewed the full-text sources (n = 205) sequentially, beginning with compilations and blended models known to the workgroup members, and proceeding to review sources identified through the database search and expert query. Any information pertaining to the form or substance of an implementation strategy or its definition was extracted. When a source described a multifaceted or blended implementation strategy, an attempt was made to reduce them to their discrete strategy components. A provisional compilation of discrete implementation strategies and working definitions was developed. The provisional compilation was edited in an iterative fashion when source materials included strategies or definitions that were novel or more nuanced than those already represented.

Group Review Process

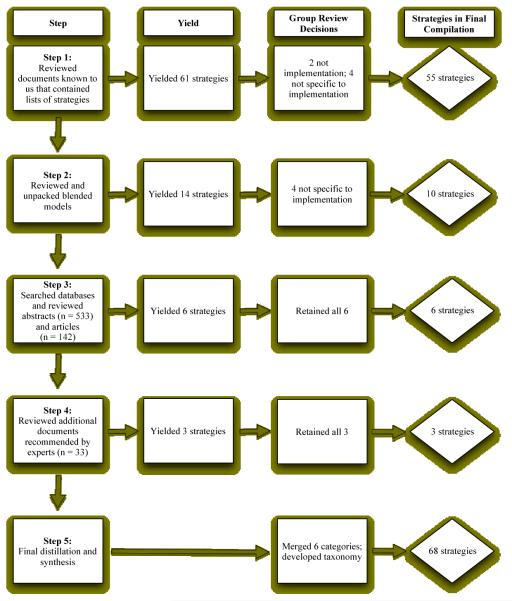

The eight-member workgroup gathered for seven face-to-face meetings over the course of one year. The first three meetings were dedicated to discussions of the state of the implementation literature and formulating a strategy to compile and define strategies that have been utilized in health and mental health. In subsequent meetings, we utilized a modified Delphi process (Fink, Kosecoff, Chassin, & Brook, 1984; Jones & Hunter, 1995) to develop consensus regarding the discrete strategies and definitions that were extracted from the literature by the primary reviewers. Prior to each of the four meetings, workgroup members were emailed the current provisional taxonomy, and were asked to review it to determine their agreement with each of the strategies and definitions listed. Each group member was to consider whether each entry: a) met our definition of an implementation strategy, b) was (or could be) sufficiently defined to provide guidance to users, c) was sufficiently distinct from other implementation strategies included in the provisional compilation, and d) could be applied to implementation of health and mental health treatments. Group meetings were used to discuss members’ concerns about the soundness of strategies and definitions, and to move towards consensus. Every work group member’s views were elicited about every strategy decision. This process occurred over the course of several meetings; thus, the workgroup members had multiple opportunities to express concern regarding the inclusion of specific strategies and definitions. Figure 1 depicts each stage of our iterative review process and details the number of strategies that were identified and incorporated into our final compilation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for building the compilation of implementation strategies

Finally, we discussed categories and subcategories to adequately represent the range of strategies presented.

Illustrations of Decision-Making and Synthesis Processes

To provide a better understanding of the decision-making and synthesis processes, we provide several examples. Several actions fell short of our definition of an implementation strategy by failing to emphasize deliberate actions to integrate health innovations. For example, we eliminated activities that occur far before a decision to adopt an evidence-based innovation occurs, such as identifying high risk and high volume diseases or assessing the evidence for a given innovation (Stetler, McQueen, Demakis, & Mittman, 2008). Though these activities are clearly important, the purpose of this article is not to identify ways to determine what innovations should be adopted, but to show how they can be implemented through the use of specific strategies. Other potential strategies were not sufficiently defined to provide guidance to those who might use them. For instance, EPOC lists “boost morale” (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) and the VA’s QUERI model lists “regular encouragement” (Stetler, et al., 2008) as implementation interventions. These activities were also not sufficiently specific to implementing health innovations, although they may remain important components of implementation processes. Several other activities such as “build teamwork,” “resolve conflicts,” and “develop relationships” were excluded for the same reason. Our decisional work also included merging strategies when they were not conceptually distinct. For example, the financial strategy “forgive loans” (Raghavan, Bright, & Shadoin, 2008) is simply one type of financial inducement to adopt a clinical innovation; thus, it was subsumed under the strategy “alter incentive and allowance structures.” Other times, we decided to split what others might have seen as one strategy in order to remain consistent with our focus on discrete strategies. For example, the EPOC taxonomy combines the identification of barriers to implementation and designing strategies to overcome them in one intervention they called “marketing” (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002). We split them into two categories (“assess for readiness and identify barriers” and “tailor strategies to overcome barriers and honor preferences”) to emphasize the distinctiveness and importance of both processes.

Results

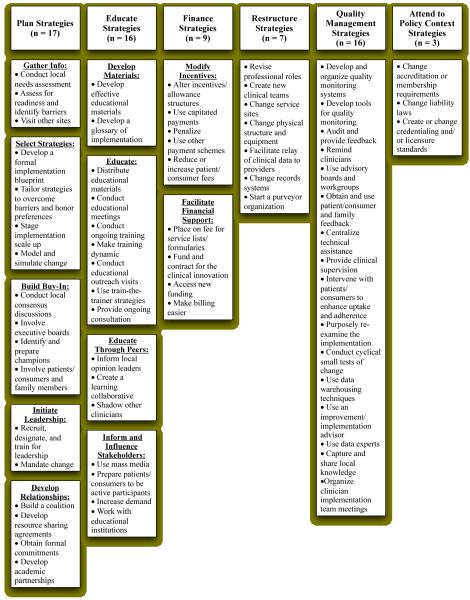

The definitions for 68 implementation strategies that emerged from our process are presented in Table 3. For presentation purposes the workgroup classified the strategies into six categories that represent larger implementation processes: planning, educating, restructuring, financing, managing quality, and attending to the policy context. Although several strategies could be placed into more than one group, we attempted to assign a primary group to each strategy. Plan strategies (n = 17) can help stakeholders gather data, select strategies, build buy-in, initiate leadership, and develop the relationships necessary for successful implementation. The educate (n = 16) category includes strategies of various levels of intensity that can be used to inform a range of stakeholders about the innovation and/or implementation effort. A number of finance strategies (n = 9) can be leveraged to incentivize the use of clinical innovations and provide resources for training and ongoing support. Strategies to restructure (n = 7) facilitate implementation by altering staffing, professional roles, physical structures, equipment, and data systems. Quality management strategies (n = 16) can be adopted to put data systems and support networks in place to continually evaluate and enhance quality of care, and ensure that clinical innovations are delivered with fidelity. Finally, strategies that attend to the policy context (n = 3) can encourage the promotion of clinical innovations through accrediting bodies, licensing boards, and legal systems. A “quick view” of the taxonomic headings, subheadings, and 68 discrete implementation strategies can be seen in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Compilation of discrete implementation strategies (N = 68)

| PLAN STRATEGIES (n = 17) | |

|---|---|

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| GATHER INFORMATION | |

| Conduct local needs assessment (Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk, 2008; Clark, Layard, Smithies, & Richards, 2009; Rugs, Hills, Moore, & Peters, 2011) |

Collect and analyze data related to the need for the innovation; this assessment could be focused on the description of usual care and its distance from evidence based care, outcomes of usual care, opinions from stakeholders on the needs for an innovation, or on special considerations for delivering the innovation in the local context. |

| Assess for readiness and identify barriers (Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, et al., 2010; Magnabosco, 2006; Norton, Amico, Cornman, Fisher, & Fisher, 2009; Schoenwald, 2010; Slavin & Madden, 1999) |

Assess various aspects of an organization to determine its degree of readiness to implement, barriers that may impede implementation, and strengths that can be used in the implementation effort. The assessment may focus on agency finances, other services provided, community support, clinician attitudes and beliefs, organizational climate and culture, structure, and decision making styles. There are also specific measures created to assess readiness to change that could be helpful (e.g., Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002; Weiner, Amick, & Lee, 2008). The readiness assessment can be used to vet or eliminate implementation sites. |

| Visit other sites (Slavin & Madden, 1999) | Visit sites where a similar implementation effort has been considered successful. |

| SELECT STRATEGIES | |

| Develop a formal implementation blueprint (Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, et al., 2010; Grol & Wensing, 2005; Massoud, et al., 2006; Norton, et al., 2009; Sosna & Marsenich, 2006) |

Develop a formal implementation blueprint that integrates multiple strategies from multiple levels or domains (e.g., staffing, funding, monitoring) using multiple theories or the use of an explicit theoretical framework. Use and update this plan to guide the implementation effort over time. |

| Tailor strategies to overcome barriers and honor preferences (Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Tailor the implementation effort to address barriers and to honor stakeholder preferences that were identified through earlier data collection. |

| Stage implementation scale up (Stetler, McQueen, Demakis, & Mittman, 2008; Thompson, Taplin, McAfee, Mandelson, & Smith, 1995) |

Phase implementation efforts by starting with small pilots or demonstration projects and gradually moving to system-wide rollout. |

| Model and simulate change (Eccles, et al., 2007; Hovmand & Gillespie, 2008; Hysong, et al., 2009) |

Model or simulate the change that will be implemented prior to implementation. These efforts could involve computer simulations, walk-through simulation exercises, or modeling the overall impact of clinicians’ intentions to change their clinical behaviors. |

| BUILD BUY-IN | |

| Conduct local consensus discussions (Biegel, et al., 2003; Carpinello, Rosenberg, Stone, Schwager, & Felton, 2002; Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Leeman, Baernholdt, & Sandelowski, 2007; Magnabosco, 2006; Marshall, Solomon, & Steber, 2001; Mueser, Torrey, Lynde, Singer, & Drake, 2003; Rabin, Glasgow, Kerner, Klump, & Brownson, 2010) |

Include providers and other stakeholders in discussions that address whether the chosen problem is important and whether the clinical innovation to address it is appropriate. |

| Involve executive boards (Hysong, Best, & Pugh, 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Involve existing governing structures (e.g., boards of directors, medical staff boards of governance) in the implementation effort, including the review of data on implementation processes. |

| Identify and prepare champions (Biegel, et al., 2003; Hysong, et al., 2007; Leeman, et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Cultivate relationships with people who will champion the clinical innovation and spread the word of the need for it. This strategy includes preparing individuals for their role as champions. Champions can be internal or external to the organization. |

| Involve patients/consumers and family members (Birkel, Hall, Lane, Cohan, & Miller, 2003; Carpinello, et al., 2002; Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, Bright, & Shadoin, 2008) |

Engage or include patients/consumers and families in all phases of the implementation effort, including training in the clinical innovation, and advocacy related to the innovation effort. |

| INITIATE LEADERSHIP | |

| Recruit, designate, and train for leadership (Leeman, et al., 2007; Massoud, et al., 2006; Wensing, Bosch, & Grol, 2009) |

Recruit, designate, and train leaders for the change effort. Change efforts require certain types of leaders, and organizations may need to recruit accordingly, rather than assuming that their current personnel can implement the change. Designated change leaders can include an executive sponsor and a day-to-day manager of the effort. |

| Mandate change (Wensing, Weijden, & Grol, 1998) |

Declare that the innovation will be implemented. |

| DEVELOP RELATIONSHIPS | |

| Build a coalition (Rabin, et al., 2010; Rugs, et al., 2011) |

Recruit and cultivate relationships with partners in the implementation effort. Partnerships can develop around cost-sharing, shared resources, shared training, and the division of responsibilities among partners. This work may proceed naturally from local consensus discussions. |

| Develop resource sharing agreements (Reed, Fong, & Pearson, 1995) |

Develop partnerships with organizations that have resources needed to implement the innovation. As an example, a group of providers could strike a relationship with a microbiology lab to conduct specialized lab work needed to implement an innovation efficiently. |

| Obtain formal commitments (Magnabosco, 2006) |

Obtain written commitments from key partners that state what they will do to implement the innovation. |

| Develop academic partnerships (Proctor, 2007; Spoth, Clair, Greenberg, Redmond, & Shin, 2007) |

Partner with a university or academic unit for the purposes of shared training and bringing research skills to an implementation project. |

| EDUCATE STRATEGIES (n =16) | |

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| DEVELOP MATERIALS | |

| Develop effective educational materials (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; Corrigan, Steiner, McCracken, Blaser, & Barr, 2001; Dobbins, et al., 2009; Magnabosco, 2006; Mueser, et al., 2003; Wensing, et al., 1998) |

Develop and format guidelines, manuals, toolkits and other supporting materials in ways that make it easier for stakeholders to learn about the innovation and for clinicians to learn how to deliver the clinical innovation. Create eye-catching, easy to use documents. Distill complex information into easier-to-learn components. Consider teaching skills modularly. Use different forms of media. Target messages for different audiences. |

| Develop a glossary of implementation (Rabin, Brownson, Joshu-Haire, Kreuter, & Weaver, 2008; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Develop a glossary to promote common understanding about implementation among the different stakeholders. |

| EDUCATE | |

| Distribute educational materials (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006; Mueser, et al., 2003; Sosna & Marsenich, 2006) |

Distribute educational materials (including guidelines, manuals and toolkits) in person, by mail, and/or electronically. |

| Conduct educational meetings (Biegel, et al., 2003; Carpinello, et al., 2002; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Davis & Davis, 2009; Gilbody et al., 2003; Leeman, et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006; Wensing & Grol, 2005) |

Hold meetings targeted toward providers, administrators, other organizational stakeholders, and community, patient/consumer, and family stakeholders to teach them about the clinical innovation. |

| Conduct ongoing training (Chamberlain, et al., 2008; Clark, et al., 2009; Magnabosco, 2006; McHugh & Barlow, 2010) |

Plan for and conduct training in the clinical innovation in an ongoing way. This can include follow-up training, advanced training, booster training, purposefully spaced training, training to competence, integration of off-the-job and on-the-job training, the introduction of concepts in a specific sequence to ensure mastery, and trainings based on the level of clinician knowledge. Trainings can be in-person, on the web, or technology-assisted. |

| Make training dynamic (Davis & Davis, 2009) |

Vary the information delivery methods to cater to different learning styles and work contexts, and shape the training in the innovation to be interactive. This includes efforts to divide material into small time intervals and the use of small group breakouts, audience response systems, and other measures. |

| Conduct educational outreach visits (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Eccles & Foy, 2009) |

Use a trained person who meets with providers in their practice settings to educate providers about the clinical innovation with the intent of changing the provider’s practice. The term academic detailing is often used synonymously. |

| Use train-the-trainer strategies (Biegel, et al., 2003; Chamberlain, et al., 2008; Magnabosco, 2006; McHugh & Barlow, 2010; Schoenwald, 2010) |

Train designated clinicians or organizations to train others in the clinical innovation. Determine whether clinicians trained as trainers are eligible to train others as train the trainers. |

| Provide ongoing consultation (Biegel, et al., 2003; Carpinello, et al., 2002; Chamberlain, et al., 2008; Corrigan, et al., 2001; McHugh & Barlow, 2010) |

Provide clinicians with continued consultation with an expert in the clinical innovation. This could include in-person or distance consultation and feedback on taped clinical encounters. This consultation is tailored to the clinician’s actual practice, to differentiate it from ongoing training. This feedback may be from a consultant external to the organization, which distinguishes it from clinical supervision. |

| EDUCATE THROUGH PEERS | |

| Inform local opinion leaders (Biegel, et al., 2003; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Eccles & Foy, 2009; Leeman, et al., 2007; Sisk, Greer, Wojtowycz, Pincus, & Aubry, 2004) |

Inform providers identified by colleagues as opinion leaders or “educationally influential” about the clinical innovation in the hopes that they will influence colleagues to adopt it. |

| Create a learning collaborative (Carpinello, et al.,2002; Davis & Davis,2009; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003;Magnabosco, 2006;Markiewicz, Ebert,Ling, Amaya-Jackson, & Kisiel,2006; Sosna & Marsenich, 2006) |

Develop and use groups of providers or provider organizations that will implement the clinical innovation and develop ways to learn from one another to foster better implementation. This is called several things in the literature including peer consultation networks, online communities of practice, quality circles, and learning collaboratives. |

| Shadow other clinicians (Magnabosco, 2006) |

Have clinicians shadow other clinicians who are expert or knowledgeable in the clinical innovation and have implemented it. |

| INFORM & INFLUENCE STAKEHOLDERS | |

| Use mass media (Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006; Sanders & Turner, 2002) |

Use media to reach large numbers of people to spread the word about the clinical innovation. |

| Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants (Wensing, Elwyn, & Grol, 2005) |

Prepare patients/consumers to be active in their care, to ask questions, and specifically to inquire about care guidelines, the evidence behind clinical decisions, or about available evidence-supported treatments. |

| Increase demand (Wensing, et al., 2009) |

Attempt to influence the market for the clinical innovation to increase competition intensity and to increase the maturity of the market for the clinical innovation. |

| Work with educational institutions (Magnabosco, 2006; Proctor, 2007) |

Encourage educational institutions to train clinicians in the innovation. |

| FINANCE STRATEGIES (n = 9) | |

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| MODIFY INCENTIVES | |

| Alter incentive/ allowance structures (Carpinello, et al., 2002; Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Leeman, et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, et al., 2008) |

Work to incent the adoption and implementation of the clinical innovation. The incentive could be in the form of an increased rate of pay to cover the incremental costs associated with implementing the clinical innovation. The incentive could be through loan reduction/forgiveness to clinicians as an incentive to learn an innovation. This category of financial strategies also includes the elimination of any perverse incentives (incentives that become a barrier to receiving appropriate care). An incentive suggests the payment is tied to performing the clinical action. An allowance suggests that the clinician is not required to perform the clinical action. |

| Use capitated payments (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Pay providers a set amount per patient/consumer for delivering clinical care. This is an implementation strategy to the degree that it frees the clinician to provide services that they may have been disincented to provide under a fee-for-service structure. This may be helpful to motivate clinicians to use certain clinical innovations. |

| Penalize (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Penalize providers financially for failure to implement or use the clinical innovation. |

| Use other payment schemes (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, et al., 2008) |

Introduce such payment approaches (in a catch-all category) as pre- payment and prospective payment for service, provider salaried service, the alignment of payment rates with the attainment of patient/consumer outcomes, and the removal or alteration of billing limits (such as numbers of encounters that are reimbursable). These are implementation strategies to the degree that they free the clinician to provide the clinical innovation. Others motivate the clinician to provide better service. |

| Reduce or increase patient/consumer fees (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Create fee structures where patients/consumers pay less for preferred treatments (the clinical innovation) and more for less preferred treatments. |

| FACILITATE FINANCIAL SUPPORT | |

| Place on fee for service lists/ formularies (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Raghavan, et al., 2008) |

Work to place the clinical innovation on lists of actions for which providers can be reimbursed (e.g., a drug is placed on a formulary, a procedure is now reimbursable). |

| Fund and contract for the clinical innovation (Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, et al., 2008; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

[Governments and other payers of services] issue requests for proposals to deliver the innovation, use contracting processes to motivate providers to deliver the clinical innovation, and develop new funding formulas that make it more likely that providers will deliver the innovation. |

| Access new funding (Biegel, et al., 2003; Magnabosco, 2006; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Access new or existing money to facilitate the implementation. This could involve new uses of existing money; accessing block grants; shifting funding from one program to another; cost sharing; passing new taxes; raising private funds; or applying for grants. |

| Make billing easier (Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, et al., 2008) |

Make it easier to bill for the clinical innovation. This might involve requiring less documentation; “block” funding for delivering the innovation; and creating new billing codes for the innovation. |

| RESTRUCTURE STRATEGIES (n = 7) | |

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| Revise professional roles (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, et al.; 2010; Schoenwald, 2010) |

Shift and revise roles among professionals who provide care and redesign job characteristics. This includes the expansion of roles in order to cover provision of the clinical innovation and the elimination of service barriers to care, including personnel policies. |

| Create new clinical teams (Clark, et al., 2009; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Change who serves on the clinical team, adding different disciplines and different skills to make it more likely that the clinical innovation is delivered or more successful. |

| Change service sites (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Change the location of clinical service sites to increase access; includes co-locating different services in order to better implement complex clinical innovations that require multiple disciplines or services. |

| Change physical structure and equipment (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Leeman, et al., 2007) |

Change the physical structure and equipment (changing the layout of a room, adding equipment). |

| Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Shojania, McDonald, Wachter, & Owens, 2004) |

Collect new clinical information from the patient/consumer and relay it to the provider outside of the traditional clinical encounter to prompt the provider to use the clinical innovation. Examples might include depression scores from an instrument administered in the waiting room or telephone transmission of blood pressure measurements. |

| Change records systems (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Hysong, et al., 2007; Leeman, et al., 2007) |

Change records systems to allow better assessment of implementation or of outcomes of the implementation. |

| Start a purveyor organization (Schoenwald, 2010) |

Start a separate organization that is responsible for disseminating the clinical innovation. It could be a for-profit or non-profit organization. It could be “licensed” by a university if the innovation was born within an academic setting. |

| QUALITY MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES (n = 16) | |

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| Develop and organize quality monitoring systems (Carpinello, et al., 2002; Chamberlain, et al., 2008; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Flynn, Cafarelli, Perakos, & Christophersen, 2007; Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, et al., 2010; Hysong, et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006; McHugh & Barlow, 2010; Schoenwald, 2010; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Develop and organize systems and procedures that monitor clinical processes and/or outcomes for the purpose of quality assurance and improvement. This includes developing systems for monitoring through peer reviews, collecting data from patients/consumers, clinicians, and supervisors, and using administrative and electronic record data. This category of strategies also includes the design of disease-specific clinical registries, where clinical information and tools (graphical representations, real-time report cards, comparisons to benchmarks, etc) are available to care team members. These systems may inform audit and feedback strategies. |

| Develop tools for quality monitoring (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Hysong, et al., 2009; Leeman, et al., 2007) |

Develop, test, and introduce into quality-monitoring systems the right input - the appropriate language, protocols, algorithms, standards, and measures (of processes, patient/consumer outcomes, and implementation outcomes) that are often specific to the innovation being implemented. |

| Audit and provide feedback (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Foy & Eccles, 2009; Hysong, et al., 2009; Leeman, et al., 2007) |

Collect and summarize clinical performance data over a specified time period and give it to clinicians and administrators in the hopes of changing provider behavior. The summary may include recommendations. The information may have been obtained from a variety of sources, including medical records, computerized databases, observation, or feedback from patients. A performance evaluation could also be considered as audit and feedback if it included specific information on clinical performance. |

| Remind clinicians (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Gupta & McKibbon, 2009; Leeman, et al., 2007) |

Develop reminder systems designed to prompt clinicians to recall information or use the clinical innovation. The reminder could be patient or encounter specific, provided verbally, on paper, or on a computer screen. Computer-aided decision support and drug dosages are included in this strategy. |

| Use advisory boards & workgroups (Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005; Glisson, et al., 2010; Hysong, et al., 2007; Leeman, et al., 2007; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Involve multiple kinds of stakeholders in a group to oversee implementation efforts and make recommendations. |

| Obtain and use patient/consumer and family feedback (Birkel et al., 2003; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Use mechanisms to increase patient/consumer and family feedback on the implementation effort. This could include complaint forms, or methods to funnel feedback to advisory boards. |

| Centralize technical assistance (Biegel, et al., 2003; Clark, et al., 2009; Massoud, et al., 2006; Sosna & Marsenich, 2006; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Develop and use a system to deliver technical assistance focused on implementation issues. This could be the designation of a lead technical assistance organization (could also be responsible for training). The lead technical assistance entity can develop other mechanisms (e.g., call-in lines or web sites) to share information on how to best implement the clinical innovation. |

| Provide clinical supervision (Carpinello, et al., 2002; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Provide clinicians with ongoing supervision. Provide training for clinical supervisors who will supervise clinicians who provide the innovation. |

| Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence (Wensing, et al., 2005) |

Intervene with patients/consumers to increase uptake of and adherence to clinical treatments. This includes consumer/patient reminders and financial incentives to attend appointments. |

| Purposefully re- examine the implementation (Grol & Wensing, 2005a; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Obtain commitment from stakeholders to use monitoring to adjust practice and strategies to continuously improve the implementation effort and delivery of the clinical innovation. |

| Conduct cyclical small tests of change (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003; Leeman, et al., 2007; Shapiro & Donaldson, 2008) |

Implement changes in a cyclical fashion using small tests of change before taking changes system-wide. Results of the tests of change are studied for insights on how to do better. This process continues serially over time and refinement is added with each cycle. Two common small tests of change cycling strategies are “Plan-Do-Study- Act” (PDSA) from Deming’s quality management work and six sigma’s Define- Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DCMA) sequence. |

| Use data warehousing techniques (Hysong, et al., 2007) |

Integrate clinical records across facilities and organizations in order to facilitate implementation across systems. |

| Use an improvement/ implementation advisor (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003; Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Seek guidance from experts in implementation. This could include consultation with outside experts such as university-affiliated faculty members, or hiring quality improvement experts or implementation professionals. |

| Use data experts (Stetler, et al., 2008) |

Involve, hire and/or consult experts in data management to shape use of the considerable data that implementation efforts can generate. |

| Capture and share local knowledge (Massoud, et al., 2006) |

Capture local knowledge from implementation sites on how implementers and clinicians made something work in their setting and then share it with other sites (see centralized technical assistance and learning collaboratives). |

| Organize clinician implementation team meetings (Rapp, et al., 2008) |

Develop and support teams of clinicians who are implementing the innovation and give them protected time to reflect on the implementation effort, share lessons learned, and support one another’s learning. |

| ATTEND TO POLICY CONTEXT (n = 3) | |

| STRATEGY | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS |

| Change accreditation or membership requirements (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006) |

Strive to alter accreditation standards so that they require or encourage use of the clinical innovation. Work to alter membership organization requirements so that those who want to affiliate with the organization are encouraged or required to use the clinical innovation. |

| Change liability laws (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002) |

Participate in liability reform efforts that make clinicians more willing to deliver the clinical innovation. |

| Create or change credentialing and/or licensure standards (Biegel, et al., 2003; Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group, 2002; Magnabosco, 2006; Raghavan, et al., 2008) |

Create an organization that certifies clinicians in the innovation or encourages an existing organization to do so. Change governmental professional certification or licensure requirements to include delivering the innovation. Work to alter continuing education requirements to shape professional practice toward the innovation. |

Figure 2.

“Quick view” of the compilation of discrete implementation strategies

Strategy definitions are presented without attention to the type of actor who would typically perform the strategy. For example, some strategies are most likely enacted by a payer of clinical services, whereas others are enacted by administrators, clinicians, etc. Each of the strategies included in Table 3 includes references to some of the sources that named, defined, or discussed them. These references are meant to be illustrative. In most cases, we do not provide every reference that mentioned the use of a given strategy, as doing so would result in an unwieldy list of references for the most commonly used strategies. In a small number of cases, the cited source could be considered inspirational, in that not enough information was provided on the strategy to determine with certainty what the authors meant; the definition listed is our best guess of what was intended.

Discussion

This compilation contributes to implementation practice and research by highlighting the range of available strategies and clarifying their description. It can help facilitate the development of multifaceted, multilevel implementation plans that are tailored to local contexts. Though implementation scholars have noted the importance of addressing multiple barriers to change at multiple levels of the implementation context (Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Solberg, 2000; Solberg, et al., 2000; Wensing, Bosch, & Grol, 2009), the literature is only beginning to describe processes to help innovators build comprehensive blueprints for implementation from known strategies. Grol and Wensing (Grol & Wensing, 2005a, 2005b) suggest an approach tailored to the implementation situation, linking specific strategies to known features of the innovation, the setting, and the target of behavior change. They encourage implementers to think in terms of phases (Grol & Wensing, 2005b), starting with strategies that make stakeholders aware of the innovation and moving toward those that integrate and maintain the innovation in usual care. They caution that “a balance must be reached between the possibility of reaching the desired effects and the amount of money, time, effort and personal commitment invested and the commotion they may cause” (Grol & Wensing, 2005a, p. 53). Ultimately, implementation research is an applied science, and strategies will need to be adapted to local situations and contexts. We hope this compilation will aid in that process.

This compilation may also facilitate the conduct of implementation research. For instance, it can help researchers to develop multifaceted “enhanced implementation strategies” that can be compared to more standard approaches to implementation. Similarly, the compilation may highlight strategies that have not been empirically evaluated in a given context (in isolation or in combination), which would serve to stimulate comparative effectiveness research. Furthermore, specifying the discrete components of such approaches will allow researchers to develop protocols that outline the elements that must be present if the strategies are to be delivered with fidelity. Indeed, assessing the frequency, intensity, and fidelity in which implementation strategies are developed may be an important next step in implementation research as we struggle to understand the variability in the effectiveness of specific implementation strategies. Finally, the compilation could be adapted to serve as an audit tool to assess the types of strategies that are being employed in “real world” care and/or in implementation research.

Limitations

This effort to compile implementation strategies is limited in several ways. If we had started our iterative process with different source documents, our strategy titles and definitions may have differed. Similarly, a different composition of workgroup members could have led to different decisions. Despite our efforts to improve the consistency and clarity of the description of strategies, this compilation represents only a step toward achieving that goal. Addressing the “Tower of Babel” problem identified by McKibbon and colleagues (McKibbon, et al., 2010) would likely require an international consensus group of leaders in implementation research. Certainly, we would be among the first to support such an effort; however, in absence of that, we believe this compilation contributes to the advancement of clarity in the field.

There are also limitations inherent to our search strategy. A broader search strategy that included non-English language sources may have revealed a greater number of strategies. Nevertheless, our purpose was not to capture every possible strategy that could be used in health and mental health, but to highlight the range of available strategies by consolidating and extending other compilations and reviews.

This compilation does not address geographical variations in the organization and financing of health and mental healthcare, and we were unable to identify regional-level implementation strategies, which deserve further attention in the literature. Thus, it is possible that some of the strategies included in the compilation are more readily applicable to the U.S. healthcare system, and that some strategies that are particularly relevant within other nations’ healthcare systems are absent. Nevertheless, our expert query involved an international body of scholars, and we believe that the majority of the strategies included in the compilation are broadly applicable.

This compilation does not address the empirical evidence for included strategies. Though future work could certainly address this element, our priority here was to highlight the range of options available to stakeholders rather than perpetuate the notion that there are a limited number of options available by focusing on those with the most empirical support.

Finally, it was beyond the scope of this article to discuss the explicit theoretical underpinnings of each included strategy (though there are implicit links to the dimensions of the CFIR). While some scholars have debated the utility of theory (Bhattacharyya, Reeves, Garfinkel, & Zwarenstein, 2006), many have emphasized the use of behavioral change theories and broader theoretical models of implementation in the design and selection of implementation strategies (Damschroder, et al., 2009; Grol, Bosch, Hulscher, Eccles, & Wensing, 2007; The Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG), 2006). Future work could make the theoretical underpinnings of each individual strategy more explicit.

Conclusion

It is our hope that this consolidated compilation will play a role in expanding the range of strategies that are both utilized and tested empirically. Yet, the list of strategies and definitions compiled here should not be considered the last word. There are likely strategies in use that are not represented in our compilation. Furthermore, this is a new field, with substantial need and promise for innovation. We welcome suggestions for additions to this list.

References

- Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Getting research findings into practice: Closing the gap between research and practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. British Medical Journal. 1998;317(7156):465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Garfinkel S, Zwarenstein M. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions: Fine in theory, but evidence of effectiveness in practice is needed. Implementation Science. 2006;1(5) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegel DE, Kola LA, Ronis RJ, Boyle PE, Reyes CMD, Wieder B, et al. The Ohio substance abuse and mental illness coordinating center of excellence: Implementation support for evidence-based practice. Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13(4):531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JM, Titler MG, Ardery G, Herr K. Effect of evidence-based acute pain management practices on inpatient costs. Health Services Research. 2009;44(1):245–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana MD, Rushton JL, Rush AJ. Implementing practice guidelines for depression: Applying a new framework to an old problem. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2002;24(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpinello SE, Rosenberg L, Stone J, Schwager M, Felton CJ. New York State’s campaign to implement evidence-based practices for people with serious mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(2):153–155. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaillet N, Dube E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: A systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;108(5):1234–1245. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000236434.74160.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare. 2008;87(5):27–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2005;11:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Layard R, Smithies R, Richards DA. Improving access to psychological therapy: Initial evaluation of two UK demonstration sites. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:910–920. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group Data Collection Checklist. 2002:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Steiner L, McCracken SG, Blaser B, Barr M. Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1598–1606. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ. Organizational interventions to encourage guideline implementation. Chest. 2000;118(2):40S–46S. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2_suppl.40s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(50):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, Davis N. Educational interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers M. The task force on systematic reviews and guidelines: The value of traditional reviews in the era of systematic reviewing. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:423–430. doi: 10.1097/phm.0b013e31819c59c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Foy R. Linkage and exchange interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science. 2006;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Armstrong D, Baker R, Cleary K, Davies H, Davies S, et al. An implementation research agenda. Implementation Science. 2009;4(18) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E. Organizational intervention. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. pp. 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, Brook RH. Consensus methods: Characteristics and guidelines for use. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74(9):979–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.9.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature (No. FMHI Publication #231) University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; Tampa, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn FM, Cafarelli M, Petrakos K, Christophersen P. Improving outcomes for acute coronary syndrome patients in the hospital setting: Successful implementation of the American Heart Association “get with the guidelines” program by phase I cardiac rehabilitation nurses. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2007;22(3):166–176. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000267824.27449.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy R, Eccles MP. Audit and feedback interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Wiley: Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. pp. 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: A systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7(4):243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstrong KS, Chapman JE. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(4):537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, Mowatt G, Fraser C, Bero L, et al. Changing provider behavior: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical Care. 2001;39(8, Supplement 2):II-2–II-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technology Assessment. 2004;8(6) doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Ramsay C, Fraser C, et al. Toward evidence-based quality improvement. Evidence (and its limitations) of the effectiveness of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies 1966-1998. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00357.x. doi: JGI357 [pii] 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. BMJ. 1997;315:418–425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7105.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Improving the quality of medical care. JAMA. 2001;284:2578–2585. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Wensing M. Effective implementation: A model. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: The implementation of change in clinical practice. Elsevier; Edinburgh: 2005a. pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Wensing M. Selection of strategies. In: Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: The implementation of change in clinical practice. Elsevier; Edinburgh: 2005b. pp. 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Bosch MC, Hulscher MEJL, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. The Milbank Quarterly. 2007;85(1):93–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, editors. Improving patient care: The implementation of change in clinical practice. Elsevier; Edinburgh: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, McKibbon KA. Informatics interventions. In: Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, editors. Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley M. Systematic or unsystematic, is that the question? Some reflections on the science, art, and politics of reviewing research evidence; Paper presented at the Public Health Evidence Steering Group of the Health Development Agency; 2002; www.nice.org.uk/download.aspx?o=508244. [Google Scholar]

- Hysong SJ, Best RG, Pugh JA. Clinical practice guideline implementation strategy patterns in veterans affairs primary care clinics. Health Services Research. 2007;42(1):84–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement . The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Initial national priorities for comparative effectiveness research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. Mission drift in qualitative research, or moving toward a systematic review of qualitative studies, moving back to a more systematic narrative review. The Qualitative Report. 2004;9(1):95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kato WJ, Zatzick D, Bond G, Williams J. Dissemination of evidence-based mental health interventions: Importance to the trauma field. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(5):611–623. doi: 10.1002/jts.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman J, Baernholdt M, Sandelowski M. Developing a theory-based taxonomy of methods for implementing change in practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(2):191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: Who should do what? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1993;703:226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madon T, Hofman KJ, Kupfer L, Glass RI. Public health. Implementation science. Science. 2007;318:1728–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1150009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]