Abstract

Selective intestinal decontamination (SID) with norfloxacin has been widely used for the prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) because of a high recurrence rate and preventive effect of SID for SBP. However, it does select resistant gut flora and may lead to SBP caused by unusual pathogens such as quinolone-resistant gram-negative bacilli or gram-positive cocci. Enterococcus hirae is known to cause infections mainly in animals, but is rarely encountered in humans. We report the first case of SBP by E. hirae in a cirrhotic patient who have previously received an oral administration of norfloxacin against SBP caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and presented in septic shock.

Keywords: Enterococcus hirae, Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis, Sepsis, Liver Cirrhosis

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is the most common infection with a high morbidity and mortality, occurring in 10% to 30% of cirrhotic patients with ascites, and associated with a very high rate of recurrence (1). Prophylaxis based on selective intestinal decontamination (SID) with oral antibiotics such as quinolones and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, therefore, has been recommended to reduce the rate of recurrence and initial occurrence of SBP. However, this approach potentially selects highly resistant gram-negative bacilli and may lead to the emergence of gram-positive cocci. Consequently, recent studies have virtually demonstrated the increased proportion of quinolone-resistant bacteria or gram-positive cocci as a causative agent in SBP, though predominant microbiologic findings are still gram-negative bacteria (2).

Enterococci, gram-positive facultative anaerobes, are part of the normal gut flora. The main pathogenic species in humans are E. faecalis and E. faecium, which have become an important cause of nosocomial infections. Other enterococcal species are occasionally associated with human infection. E. hirae is known to cause infection in animals, but is rarely isolated in human clinical samples (3).

We recently experienced SBP caused by E. hirae, an unusual pathogen in humans, which was the first case of SBP with septicemia in a cirrhotic patient to our knowledge. Herein, we report the case together with a review of the literature.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 61-yr-old male with decompensated cirrhosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to emergency room because of abdominal pain, fever, chills and generalized weakness on November 20th, 2011. He had been diagnosed as alcoholic liver cirrhosis 5 yr ago and followed up with regular examinations. He had received norfloxacin (400 mg per day) for secondary prevention of SBP after hospitalization by Klebsiella pneumoniae-associated SBP 4 months ago. He looked vitally stable at first with blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg, heart rate of 92 beats/min, and body temperature of 39.3℃. However, blood pressure rapidly declined to 80/50 mmHg in 3 hr of admission, which prompted a sufficient fluid replacement and even inotropics. On physical examination, his abdomen was protuberant, but there was no tenderness and rebound tenderness. The rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Initial laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) 7,590/µL with left deviation (neutrophil 90%), hemoglobin 13.4 g/dL, platelet 87,000/µL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 50.2 mg/L, total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL, albumin 2.7 g/dL, INR 1.63, aspartate transaminase 16 IU/L, alanine transaminase 9 IU/L, serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dL. Based on the finding of physical and laboratory examination, his stage of cirrhosis was classified as Child-Pugh class C. Analysis of ascitic fluid revealed a WBC count of 6,560/µL with 90% neutrophil and a red blood cell count of 1,440/µL, the protein levels of 1.6 g/dL, albumin levels of 0.7 g/dL. Urinalysis, chest X-ray and electrocardiography were normal.

Intravenous cefotaxime (2 g every 12 hr) was empirically started on the presumptive diagnosis of SBP, pending the results of culture. Two days even after antibiotic coverage, the patient was still febrile and laboratory findings did not improve in terms of serum CRP (138 mg/dL) and WBC count in the ascitic fluid. Antibiotics were changed to vancomycin (1 g every 12 hr) combined with ciprofloxacin (200 mg every 12 hr) when gram positive cocci were isolated in both ascitic fluid and blood cultures. Subsequently, fever subsided and laboratory findings were gradually improved.

Ascitic fluid and blood cultures obtained on admission yielded an Enterococcus spp., which was identified at the species level as E. hirae using automated MicroScan WalkAway system (Microscan® WalkAway®-96 Plus, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., CA, USA) and sucrose fermentation test. The strain was sensitive to ampicillin, vancomycin, teicoplanin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and high-level streptomycin and gentamicin. According to antibiotic sensitivity test, it was replaced by intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hr). The patient was clinically resolved and discharged without complications on December 7th, 2011.

DISCUSSION

Enterococci have been increasingly identified as important causes of severe infections in humans, such as septicemia, endocarditis and urinary tract infections. There are more than 20 recognized species within the genus Enterococcus, in which E. faecalis and E. faecium account for up to 90% of the clinical isolates (4). Other enterococcal species are rarely isolated, although the increased prevalence of unusual species of enterococci and the emergence of multidrug resistance have been emphasized recently (5).

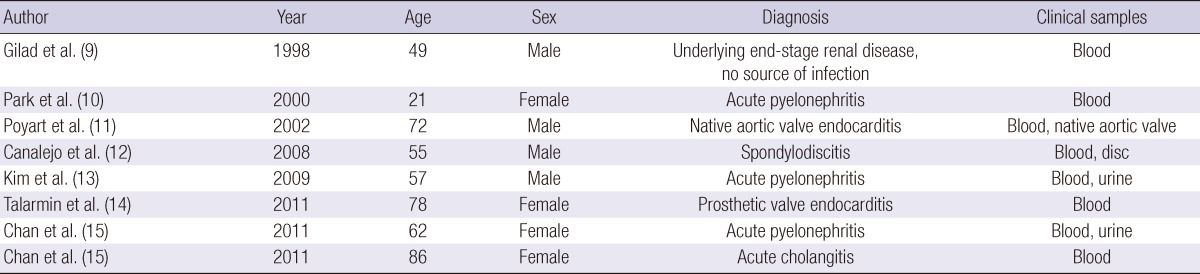

E. hirae, originally described by Farrow and Collins in 1985 (6), is known to cause infections in different animals species (chickens, rats, birds and cats) (7, 8), but is very rare in humans. To the knowledge, there are only eight case reports describing human infection in the literatures (Table 1) (9-15). Our case constitutes the first description of SBP as well as the ninth case of clearly established human infection caused by E. hirae. It is practically difficult to differentiate E. durans and E. hirae due to similarity in phenotypic and biochemical activity, and they might be misidentified using phenotypic methods. It, therefore, might require a genetic method for the exact identification of strains at the species level. E. durans and E. hirae differ by two fermentation sugar tests: acid production by using raffinose and sucrose tend to be positive with E. hirae but negative with E. durans. Therefore, sugar fermentation tests could be used to distinguish these strains in clinical practice. In our study, the results of sugar fermentation tests were comparable with E. hirae though the genetic assay was not done.

Table 1.

Cases of human bacteremia by E. hirae

Regarding the antimicrobial susceptibility of E. hirae, the emergence of ampicillin-resistance and high-level resistance to gentamicin has been reported, though there is little data in the literature, but, so far, fortunately glycopeptides-resistant E. hirae not reported yet (16-19).

Patients with liver cirrhosis are vulnerable to bacterial infections due to defects in various host defense mechanisms. SBP is the most common infection in cirrhotic patients followed by urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and bacteremia. Although the precise pathogenesis of SBP has not been clearly defined, overgrowth and translocation of intestinal bacteria appears to be the most important step in the pathogenic process. Despite the early diagnosis and the introduction of effective antibiotics have improved the prognosis for SBP patients, hospital mortality was still problematic. Moreover, recurrence rate reaches up to 70% during the subsequent year of the initial resolution. Therefore, the oral administration of antibiotics such as quinolones and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole have been attempted to SID of mainly aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and such trials have significantly reduced the rate of recurrence as well as initial occurrence of SBP (20). However, this approach potentially selects highly resistant gram-negative bacilli and may lead to the emergence of gram-positive cocci. It has been a problem of major concern in prophylaxis of SBP in cirrhotic patients. In our case, the patient had been treated for SBP caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae 4 months before admission with ensuing antibiotic coverage as norfloxacin for secondary prevention of SBP. It is possible that it might lead to selection of the bacterial species isolated from the patient. Intestinal E. hirae might translocate to ascites and cause SBP with septicemia in this patient who had uncontrolled ascites.

E. hirae is a rare pathogen in humans from which it is scarcely isolated. For the first time, our case illustrates the possibility of E. hirae to cause SBP and septicemia in humans.

References

- 1.Suk KT, Baik SK, Yoon JH, Cheong JY, Paik YH, Lee CH, Kim YS, Lee JW, Kim DJ, Cho SW, et al. Revision and update on clinical practice guideline for liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:1–21. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2012.18.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1646–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon S, Swenson JM, Hill BC, Pigott NE, Facklam RR, Cooksey RC, Thornsberry C, Jarvis WR, Tenover FC. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of common and unusual species of enterococci causing infections in the United States. Enterococcal Study Group. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2373–2378. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2373-2378.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray BE. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:46–65. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash VP, Rao SR, Parija SC. Emergence of unusual species of enterococci causing infections, South India. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrow JA, Collins MD. Enterococcus hirae, a new species that includes amino acid assay strain NCDO 1258 and strains causing growth depression in young chickens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etheridge ME, Yolken RH, Vonderfecht SL. Enterococcus hirae implicated as a cause of diarrhea in suckling rats. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1741–1744. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1741-1744.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devriese LA, Haesebrouck F. Enterococcus hirae in different animal species. Vet Rec. 1991;129:391–392. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.17.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilad J, Borer A, Riesenberg K, Peled N, Shnaider A, Schlaeffer F. Enterococcus hirae septicemia in a patient with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:576–577. doi: 10.1007/BF01708623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J, Uh Y, Jang IH, Yoon KJ, Kim SJ. A case of Enterococcus hirae septicemia in a patient with acute pyelonephritis. Korean J Clin Pathol. 2000;20:501–503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poyart C, Lambert T, Morand P, Abassade P, Quesne G, Baudouy Y, Trieu-Cuot P. Native valve endocarditis due to Enterococcus hirae. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2689–2690. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2689-2690.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canalejo E, Ballesteros R, Cabezudo J, García-Arata MI, Moreno J. Bacteraemic spondylodiscitis caused by Enterococcus hirae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:613–615. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HI, Lim DS, Seo JY, Choi SH. A case of pyelonephritis accompanied by Enterococcus hirae bacteremia. Infect Chemother. 2009;41:359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talarmin JP, Pineau S, Guillouzouic A, Boutoille D, Giraudeau C, Reynaud A, Lepelletier D, Corvec S. Relapse of Enterococcus hirae prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1182–1184. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02049-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan TS, Wu MS, Suk FM, Chen CN, Chen YF, Hou YH, Lien GS. Enterococcus hirae-related acute pyelonephritis and cholangitis with bacteremia: an unusual infection in humans. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012;28:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uh Y, Jang IH, Hwang GY, Yoon KJ, Lee HH. Identification and biochemical reactions of Enterococci by a simplified identification system. Korean J Clin Microbiol. 1999;2:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNamara EB, King EM, Smyth EG. A survey of antimicrobial susceptibility of clinical isolates of Enterococcus spp. from Irish hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:185–189. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massa R, Bantar C, Mollerach M, Nicola F, Murray BE, Smayevsky J, Gutkind G. Emergence in vivo of resistance to ampicillin in a clinical isolate of Enterococcus hirae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:559–561. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangan MW, McNamara EB, Smyth EG, Storrs MJ. Molecular genetic analysis of high-level gentamicin resistance in Enterococcus hirae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:377–382. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heo J, Seo YS, Yim HJ, Hahn T, Park SH, Ahn SH, Park JY, Park JY, Kim MY, Park SK, et al. Clinical features and prognosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in Korean patients with liver cirrhosis: a multicenter retrospective study. Gut Liver. 2009;3:197–204. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]