Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation is common among patients with cardiovascular disease and is a frequent complication of the acute coronary syndrome. Data are needed on recent trends in the magnitude, clinical features, treatment, and prognostic impact of pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

The study population consisted of 59,032 patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome at 113 sites in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Study between 2000 and 2007.

Results

4,494 participants (7.6%) with acute coronary syndrome reported a history of atrial fibrillation and 3,112 (5.3%) developed new-onset atrial fibrillation during their hospitalization. Rates of new-onset atrial fibrillation (5.5% to 4.5%) and pre-existing atrial fibrillation (7.4% to 6.7%) declined during the study. Pre-existing atrial fibrillation was associated with older age and greater cardiovascular disease burden, whereas new-onset atrial fibrillation was closely related to the severity of the index acute coronary syndrome. Patients with atrial fibrillation were less likely than patients without atrial fibrillation to receive evidence-based therapies and were more likely to develop in-hospital complications, including heart failure. Overall hospital death rates in patients with new-onset and pre-existing atrial fibrillation were 14.5% and 8.9%, respectively, compared to 1.2% in those without atrial fibrillation. Short-term death rates in atrial fibrillation patients declined over the study period.

Conclusions

Despite a reduction in the rates of, and mortality from, atrial fibrillation, this arrhythmia exerts a significant adverse effect on survival among patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome. Opportunities exist to improve the identification and treatment of acute coronary syndrome patients with, or at risk for, atrial fibrillation to reduce the incidence and resultant complications of this dysrhythmia.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, acute coronary syndrome, mortality

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (atrial fibrillation) is one of the most common cardiovascular diseases worldwide, and the global burden of atrial fibrillation is increasing.1,2 The acute coronary syndrome is a potent risk factor for atrial fibrillation, with atrial fibrillation occurring in up to 1 in every 5 patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome.3,4

To date, most investigations into the magnitude and impact of atrial fibrillation in the setting of an acute coronary syndrome have been limited by modest sample sizes, short duration of follow-up, and/or inclusion of less generalizable patient populations.5–7 Perhaps due to the heterogeneous nature of these investigations, there remains a lack of consensus as to whether or not, independent of underlying risk factors, the development of atrial fibrillation confers an increased risk of dying in patients with an acute coronary syndrome.5,8–12 Moreover, since studies have focused largely on patients who develop new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization for an acute coronary syndrome,13–15 the impact of pre-existing atrial fibrillation on prognosis in this setting is poorly defined.16

Despite significant changes in the demographics, treatment, and prognosis of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome over the last 30 years,17,18 limited data are available describing recent trends in the magnitude, treatment, and prognosis of patients with acute coronary syndrome and new-onset19 or pre-existing atrial fibrillation20. The purpose of this study was to describe changing trends in patients with and without atrial fibrillation enrolled in the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) Study between 2000 and 2007.

Methods

Details of the design of, and data collection methods used in, the GRACE Registry have been previously published.21 In brief, GRACE was a large, multi-national, observational study of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome.22 One hundred and thirteen hospitals from 14 countries contributed data to this investigation.

Adult patients admitted with a presumptive diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome at any of the 113 participating GRACE hospitals were considered eligible for study inclusion and patient’s eligibility status was assessed based on pre-determined criteria.21,22

Trained staff abstracted patient’s demographic, clinical, biochemical, and electrocardiographic characteristics, as well as treatment practices and hospital outcomes, from hospital medical records using standardized case reporting forms. Standardized definitions of patient-related variables and outcomes were used (www.outcomes.org/grace).21 As previously described, atrial fibrillation was defined on the basis of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter on the admission 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).20 Patients were categorized into those with pre-existing atrial fibrillation and those with new-onset atrial fibrillation based on the presence of a history of atrial fibrillation in hospital medical records.20 A GRACE risk score was calculated based on a validated 8-variable model.23

All acute coronary syndrome events were assigned to 1 of 3 categories using pre-established criteria: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and unstable angina.25,26

Data analysis

Differences in the characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation were compared to patients who remained free of this arrhythmia using the Chi square and Kruskal-Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Variables considered for inclusion in all multivariable adjusted regression models were selected on the basis of established associations with atrial fibrillation and/or reduced survival in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. Candidate variables included age, sex, current smoking status, medical history, clinical characteristics on hospital presentation, and ECG characteristics (Table 1). Variables were retained in the final regression model if they were associated with development of new-onset atrial fibrillation on univariate testing (p < 0.20). The endpoints examined included the development of cardiogenic shock, sustained ventricular tachycardia, renal failure, major bleeding, or stroke during hospitalization, in-hospital death, and death at 30-days after hospital admission.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of GRACE Participants with New-Onset, Pre-existing, and No Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

| Variable* | New-Onset AF (n=3112) |

P Value (New vs. No) |

Pre-existing AF (n=4494) |

P Value (Pre vs. No) |

No AF (n=51,426) |

P Value (New vs. Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72.1 (11.6) | <0.001 | 75.1 (10.4) | <0.001 | 64.5 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1953 (63.0%) | <0.001 | 2723 (60.8%) | <0.001 | 34891 (68.1%) | 0.059 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 (5.3) | <0.001 | 27.2 (5.6) | <0.001 | 27.8 (5.4) | 0.45 |

| Hospitalized in United States | 870 (28%) | <0.001 | 1573 (35%) | <0.001 | 11980 (23.3%) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 136.1 (32.5) | <0.001 | 140.2 (31.0) | <0.001 | 141.8 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77.0 (19.6) | <0.001 | 77.6 (19.1) | <0.001 | 80.4 (17.7) | 0.32 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 87.9 (27.5) | <0.001 | 86.8 (27.1) | <0.001 | 78.3 (19.9) | 0.02 |

| GRACE Risk Score** | 159.3 (39.2) | <0.001 | 152.9 (36.3) | <0.001 | 128.5 (36.4) | <0.001 |

| LOS (days) | 11.9 (10.9) | <0.001 | 7.7 (7.9) | <0.001 | 7.0 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical History | ||||||

| Current Smoker | 1675 (54.0%) | <0.001 | 2112 (47.2%) | <0.001 | 29994 (58.5%) | <0.001 |

| Angina | 1416 (45.6%) | <0.001 | 2730 (61.0%) | <0.001 | 25725 (50.1%) | <0.001 |

| MI | 877 (28.2%) | 0.55 | 1933 (43.2%) | <0.001 | 14738 (28.7%) | <0.001 |

| HF | 396 (12.8%) | <0.001 | 1422 (31.9%) | <0.001 | 4068 (7.9%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 395 (12.7%) | <0.001 | 979 (21.9%) | <0.001 | 9124 (17.8%) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 267 (8.6%) | <0.001 | 995 (22.2%) | <0.001 | 5984 (11.7%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 864 (27.8%) | <0.001 | 1370 (30.7%) | <0.001 | 12541 (24.4%) | 0.0076 |

| Hypertension | 2035 (65.6%) | <0.001 | 3328 (74.3%) | <0.001 | 31201 (60.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1243 (40.1%) | <0.001 | 2214 (49.8%) | 0.24 | 25064 (48.9%) | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 45 (1.4%) | 0.002 | 112 (2.5%) | <0.001 | 464 (0.9%) | 0.0016 |

| ACS Type | ||||||

| UA | 508 (16.3%) | <0.001 | 1474 (32.8%) | <0.001 | 15534 (30.2%) | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI | 1077 (34.6%) | 1864 (41.5%) | 16889 (32.8%) | |||

| STEMI | 1527 (49.1%) | 1156 (25.7%) | 19003 (36.9%) | |||

| Killip Class III and IV HF | 361 (11.8%) | <0.001 | 358 (8.2%) | <0.001 | 2048 (4.1%) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 (0.9) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.0) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 179.5 (48.4) | <0.001 | 174.6 (48.1) | <0.001 | 192.3 (49.5) | 0.0004 |

| Troponinδ | 36.0 (86.1) | <0.001 | 14.0 (43.7) | <0.001 | 23.1 (66.8) | <0.001 |

| Baseline EF (%) | 45.0 (15.2) | <0.001 | 46.4 (15.7) | <0.001 | 51.0 (14.2) | 0.0002 |

| LBBB | 203 (6.5%) | <0.001 | 421 (9.4%) | <0.001 | 2216 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

Mean (± SD), laboratory values obtained from admission

GRACE Risk Score is based on patient age, presenting heart rate, systolic blood BP, serum creatinine, Killip class, cardiac arrest on presentation, ST-segment deviation, and cardiac enzymes.23

Maximum value within first 24 hours

BP = blood pressure; BMI=body mass index; LOS = length of stay; MI = myocardial infarction; HF = heart failure; PCI = Percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; EF = ejection fraction; LBBB = left bundle branch block

Results

Of the 59,032 patients enrolled in GRACE between 2000 and 2007, 4,494 (7.6%) had pre-existing atrial fibrillation and 3,112 developed new-onset atrial fibrillation (5.3%) during hospitalization (Table 1). The mean age of study participants was 66 years, 33% were women, 10% had a history of HF, and 37% presented with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

Patients with atrial fibrillation (either new-onset or pre-existing atrial fibrillation) were on average older, female, more likely to have a left bundle branch block, a higher average GRACE risk score, a lower ejection fraction, a higher initial serum creatinine level, a longer hospital stay, and a history of heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, or major bleeding in comparison to patients without prior atrial fibrillation who remained in sinus rhythm during hospitalization (Table 1). Patients who did not develop atrial fibrillation had a significantly higher body mass index, higher blood pressure, higher serum cholesterol, and lower initial heart rate on hospital presentation than acute coronary syndrome patients with pre-existing or new-onset atrial fibrillation.

Patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely than patients who remained free from atrial fibrillation to have presented with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, have a higher initial troponin level, and were less likely to have a history of myocardial infarction, angina, hyperlipidemia, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. In contrast, patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation were more likely to have presented with a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, have a lower initial troponin level, and were more likely to have a history of MI, angina, hyperlipidemia, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting than were patients without atrial fibrillation. The exclusion of patients who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery during hospitalization did not significantly alter our study findings.

Characteristics of Patients with New-Onset vs. Pre-Existing Atrial Fibrillation

Patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation were on average younger and more likely to be hospitalized with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction than were patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.001). Patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation had a lower systolic blood pressure, a higher heart rate, a higher GRACE Risk Score, and a longer length of stay than patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.05). Patients developing new-onset atrial fibrillation during their hospital stay were more likely to currently smoke, but were less likely to have a history of various cardiovascular comorbidities and major bleeding, than patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.005). Patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely to have a lower initial serum creatinine level, total cholesterol level, and baseline ejection fraction, but higher peak troponin levels, than patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.001).

Incidence Rates of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Prevalence of Pre-existing Atrial Fibrillation

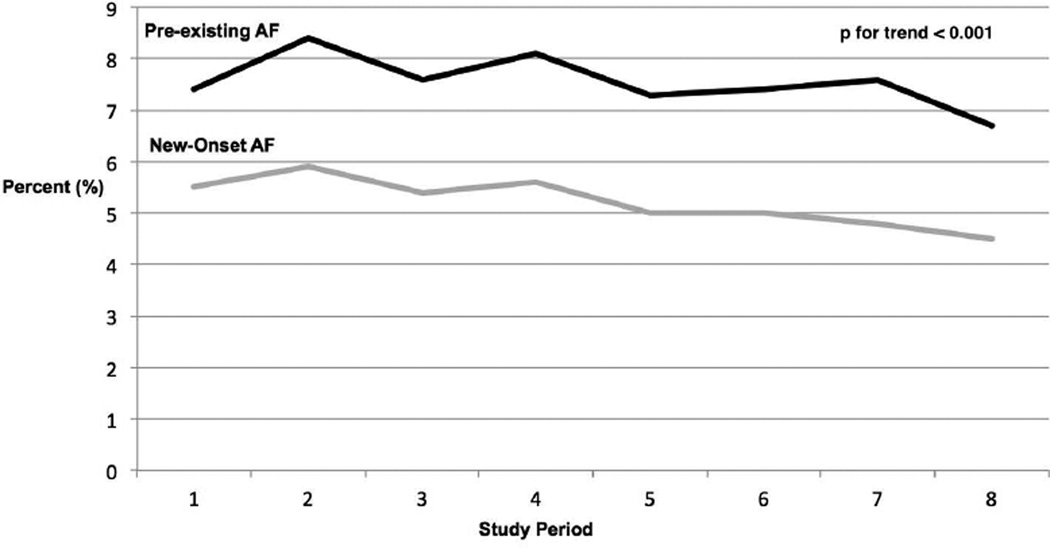

Between 2000 and 2007, incidence rates of new-onset atrial fibrillation declined, albeit in an inconsistent manner, from 5.5% to 4.5% (Figure 1, p for trend <0.001). After adjustment for several demographic and clinical factors, the multivariable adjusted odds of developing new-onset atrial fibrillation was lower during our most recent study years (2004–2007) in comparison to our original study year (2000) (Table 2). A greater proportion of GRACE participants reported a history of atrial fibrillation than developed new-onset atrial fibrillation (7.6% vs. 5.3%). The prevalence of atrial fibrillation declined from 7.4% in 2000 to 6.7% in 2007 (Figure 1, p for trend <0.001), but the adjusted odds of having pre-existing atrial fibrillation remained similar throughout the study period (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Rates of new-onset and pre-existing atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome by study year between 2000 and 2007.

Table 2.

Odds of Having Pre-existing Atrial Fibrillation or Developing New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation In Relation to Study Year

| Study Year | New-Onset AF n (%) |

Adjusted Odds New-Onset AF* |

Pre-existing AF n (%) |

Adjusted Odds Pre-Existing AF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 441 (5.5) | -- | 588 (7.4) | -- |

| 2001 | 470 (5.9) | 1.04 (0.90–1.12) | 670 (8.4) | 1.13 (1.00 – 1.29) |

| 2002 | 452 (5.4) | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | 712 (7.6) | 1.02 (0.90 – 1.16) |

| 2003 | 496 (5.6) | 1.02 (0.88–1.17) | 712 (8.1) | 1.07 (0.94 – 1.21) |

| 2004 | 408 (5.0) | 0.82 (0.71–0.96) | 600 (7.3) | 0.90 (0.79 – 1.03) |

| 2005 | 349 (5.0) | 0.85 (0.72–0.99) | 518 (7.4) | 0.89 (0.78 – 1.02) |

| 2006 | 293 (4.8) | 0.82 (0.70–0.97) | 467 (7.6) | 0.95 (0.82 – 1.09) |

| 2007 | 203 (4.5) | 0.76 (0.63–0.91) | 299 (6.7) | 0.88 (0.75 – 1.03) |

Referent year = 2000. Adjusted for age, sex, and GRACE risk score.

In-Hospital Treatment and Discharge Prescription Practices

Patients with both new-onset and pre-existing atrial fibrillation were significantly less likely to have received aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, glycoprotein IIbIIIa antagonists, and statins (Table 3). Patients with any atrial fibrillation were more likely to have received amiodarone and warfarin during hospitalization. Utilization of percutaneous coronary intervention was less common, whereas pacemaker implantation was more common, in patients with any atrial fibrillation than for patients in normal sinus rhythm. Administration of thrombolytic medications, implantation of an intra-aortic balloon pump, and CABG was more common among patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation, but less common in patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation, than in patients who did not have atrial fibrillation. Patients with pre-existing or new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely to have been discharged with a prescription for warfarin, but were less likely to be discharged on aspirin, beta-blockers, statins, and clopidogrel than patients without atrial fibrillation (Table 3).

Table 3.

In-Hospital Treatment Practices and Discharge Prescription According to Atrial Fibrillation (AF) Status

| Treatment | New-Onset AF (n=3112) |

P Value (New vs. No) |

Pre-existing AF (n=4494) |

P Value (Pre vs. No) |

No AF (n=51,426) |

P Value (New vs. Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Hospital Medications | ||||||

| Aspirin | 2902 (93.3%) | 0.05 | 3849 (86.0%) | <0.001 | 48377 (94.2%) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 2458 (79.5%) | <0.001 | 3390 (76.0%) | <0.001 | 43808 (85.7%) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 2207 (71.6%) | <0.001 | 2837 (63.7%) | 0.0024 | 33672 (65.9%) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 1905 (61.8%) | <0.001 | 2645 (59.3%) | <0.001 | 36270 (80.0%) | 0.031 |

| Clopidogrel | 1074 (52.6%) | <0.001 | 1300 (43.4%) | <0.001 | 21371 (61.1%) | <0.001 |

| Amiodarone | 1554 (50.5%) | <0.001 | 1067 (24.1%) | <0.001 | 2318 (4.6%) | <0.001 |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 1870 (60.9%) | 0.43 | 2402 (54.1%) | <0.001 | 30614 (60.2%) | <0.001 |

| Unfractionated heparin | 1746 (56.9%) | <0.001 | 1834 (41.4%) | <0.001 | 23248 (45.8%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 556 (18.2%) | <0.001 | 1317 (29.7%) | <0.001 | 1768 (3.5%) | <0.001 |

| GpIIbIIIa Inhibitor | 845 (27.6%) | 0.65 | 728 (16.4%) | <0.001 | 14185 (27.9%) | <0.001 |

| Procedures | ||||||

| PCI | 1011 (32.6%) | <0.001 | 1010 (22.6%) | <0.001 | 21036 (41.2%) | <0.001 |

| Thrombolytics | 460 (15.0%) | 0.0499 | 229 (5.2%) | <0.001 | 6985 (13.7%) | <0.001 |

| CABG | 587 (19.0%) | <0.001 | 133 (3.0%) | <0.001 | 2306 (4.5%) | <0.001 |

| IABP | 337 (11.1%) | <0.001 | 80 (1.8%) | 0.03 | 1173 (2.3%) | <0.001 |

| Permanent Pacemaker | 343 (11.3%) | <0.001 | 200 (4.5%) | <0.001 | 1250 (2.5%) | <0.001 |

| Discharge Prescription | ||||||

| Aspirin | 2121 (87.4%) | <0.001 | 2897 (79.7%) | <0.001 | 40338 (92.1%) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 1725 (71.3%) | <0.001 | 2593 (71.4%) | <0.001 | 35180 (80.6%) | 0.93 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1565 (65.0%) | 0.14 | 2235 (61.7%) | 0.03 | 27675 (63.5%) | 0.01 |

| Statin | 1529 (63.3%) | <0.001 | 2268 (62.6%) | <0.001 | 32221 (73.9%) | 0.57 |

| Clopidogrel | 649 (40.9%) | <0.001 | 893 (36.7%) | <0.001 | 16659 (56.1%) | 0.008 |

| Warfarin | 476 (20.0%) | <0.001 | 1254 (34.7%) | <0.001 | 1632 (3.8%) | <0.001 |

ACE = Angiotensin converting enzyme; PCI = Percutaneous intervention; CABG = coronary artery bypass surgery; IABP = intraaortic balloon pump

Patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely to receive each of the in-hospital treatments examined, with the exception of warfarin, than were patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.05). Patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely to be discharged on aspirin and clopidogrel, and less likely to receive a discharge prescription for warfarin, than hospitalized patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (p <0.001).

In-Hospital Complications and Thirty-Day Mortality

The frequency of most in-hospital complications was higher among patients with acute coronary syndrome and any type of atrial fibrillation than in patients free from this arrhythmia (Table 4). Complication rates were highest in those with new-onset atrial fibrillation and lowest among those who did not develop atrial fibrillation. Multivariate adjustment significantly attenuated the associations between pre-existing atrial fibrillation and the development of several in-hospital complications. However, pre-existing atrial fibrillation remained associated with the development of heart and renal failure, sustained ventricular tachycardia, and death after multivariable adjustment (Table 4). New-onset atrial fibrillation retained its strong association with all in-hospital complications, including a 2-fold higher risk of dying during hospitalization, after adjustment for several potential confounding or mediating factors. Patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation were at significantly higher risk for developing in-hospital cardiogenic shock, stroke, major bleeding, and recurrent angina than patients in normal sinus rhythm.

Table 4.

Clinical Complications According to the Presence and Type of Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

| New-Onset AF vs. No AF | Pre-existing AF vs. No AF | No AF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication | Number (%) with New- Onset AF and Complication |

Adjusted* Odds of Complication (95%CI) |

Number (%) with Pre- existing AF and Complication |

Adjusted* Odds of Complication (95%CI) |

Number (%) with No AF and Complication |

| Heart Failure | 1226 (39.7%) | 3.2(2.9–3.5) | 989 (22.1%) | 1.4(1.3–1.6) | 5610 (10.9%) |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 464 (15.0%) | 2.8(2.4–3.2) | 217 (4.8%) | 0.9(0.8–1.1) | 1695 (3.3%) |

| Sustained ventricular tachycardia | 311 (10.0%) | 3.1(2.7–3.6) | 171 (3.8%) | 1.3(1.1–1.6) | 1298 (2.5%) |

| Renal Failure | 478 (15.4%) | 3.1(2.8–3.6) | 334 (7.5%) | 1.6(1.4–1.8) | 1491 (2.9%) |

| Stroke | 68 (2.2%) | 1.97(1.4–2.7) | 45 (1.0%) | 1.2(0.9–1.7) | 312 (0.6%) |

| Major Bleeding | 212 (6.9%) | 2.1(1.8–2.5) | 145 (3.3%) | 1.1(0.9–1.3) | 1090 (2.1%) |

| In-hospital death | 452 (14.5%) | 2.0(1.8–2.3) | 398 (8.9%) | 1.3(1.1–1.5) | 1962 (3.8%) |

| 30-day post-discharge death | 63 (3.0%) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 116 (3.5%) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 480 (1.2%) |

Adjusted for age, sex, study period, and GRACE risk score

Three percent of patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation died within 30-days of discharge, whereas 3.5% of patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation and 1.2% of patients without atrial fibrillation died during this period. Only pre-existing atrial fibrillation, however, remained associated with an increased odds of dying within 30-days after discharge after adjustment for a number of potentially confounding prognostic factors (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8).

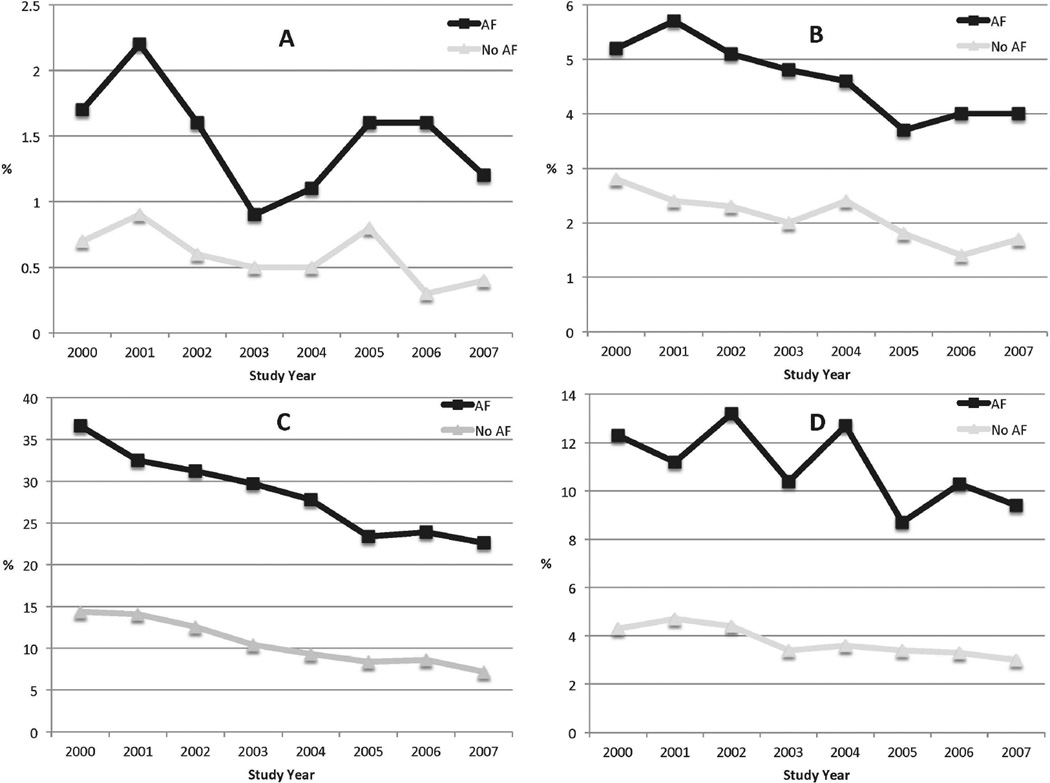

Trends in Major Hospital Complications

Although the rates of all major complications were higher among acute coronary syndrome patients with any type of atrial fibrillation (new-onset or prior), rates of in-hospital heart failure, major bleeding, and death declined in a similar fashion in patients with and without atrial fibrillation between 2000 and 2007 (p <0.05; Figure 2). However, rates of in-hospital stroke declined steadily in patients without atrial fibrillation or pre-existing atrial fibrillation, whereas the incidence rates of stroke did not decline in patients who developed new-onset atrial fibrillation. When compared to patients hospitalized during 2000, patients with atrial fibrillation hospitalized during the most recent study year (2007) were at lower risk for developing heart failure (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.39–0.64), cardiogenic shock (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45–1.01), sustained ventricular tachycardia (OR 0.65, 0.39–1.08), and in-hospital death (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43–0.99) after adjustment for potential confounders of prognostic importance (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Rates of major in-hospital complications in patients with any type atrial fibrillation (AF) hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome by study year between 2000 and 2007 (A Stroke; B Major Bleeding; C Heart Failure; D Death).

Discussion

The results of this large multinational study demonstrate that pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation are common in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome. In contrast to atrial fibrillation trends in some communities,24 the incidence rates of atrial fibrillation in acute coronary syndrome patients declined over the 8-year study period. atrial fibrillation was strongly associated with important adverse cardiac events, suggesting that opportunities exist for improving the treatment of patients with acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation. Patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation differed from patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation, suggesting that the underlying pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation in these populations may differ.

Incidence and Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation

Reported incidence rates of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome vary widely, with estimates ranging from 5 to 23%.4,20,25,26 In the present investigation, 1 in every 13 patients reported having a history of atrial fibrillation and 5.3% of patients developed atrial fibrillation during their acute hospitalization. Rates of new-onset atrial fibrillation in our study were slightly lower than those reported in a recent pooled analysis of 120,566 acute coronary syndrome patients enrolled in clinical trials over the same period, which showed an overall incidence rate of 7.5%.27 In contrast to the findings of a recent community-based study, which showed stable incidence rates of atrial fibrillation in 7,513 patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction between 1975 and 2005, the incidence of atrial fibrillation declined during our 8-year study.4 Reasons for these discrepant findings might include the more contemporary nature of our study, the inclusion of a multinational sample, as well as inclusion of patients with less severe types of acute coronary syndrome. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the rates of new-onset and previous atrial fibrillation in our study were consistent with the frequency of atrial fibrillation observed in patients enrolled in the ACS Prospective Audit Registry (4.4% new-onset, 11.4% previous atrial fibrillation).16 Since new-onset atrial fibrillation complicating myocardial infarction often results from left ventricular dysfunction and acutely increased filling pressures, greater use of coronary revascularization and effective cardiac medications may have exerted a beneficial effect on the occurrence rates of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized between 2000 and 2007.

As reported in prior investigations, older age, a greater cardiovascular risk factor burden, poorer renal and left ventricular function, and disease-specific clinical status (e.g., GRACE risk score) were associated with atrial fibrillation in our population.20 Patients with prior atrial fibrillation were also more likely to have a history of coronary heart disease and prior coronary revascularization. New-onset atrial fibrillation was associated with greater infarct size (e.g., maximum troponin level) and severity (e.g., ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), suggesting that the severity of acute coronary syndrome places patients at greater risk for developing atrial fibrillation, irrespective of their baseline cardiovascular risk factor profile.

In-Hospital Treatment and Discharge Prescription Practices

In-hospital and discharge prescription of medications known to improve prognosis from an acute coronary syndrome were lower in patients with atrial fibrillation in comparison to patients without atrial fibrillation. Although low rates of in-hospital clopidogrel and GpIIbIIIa prescription may be explained by provider concerns about the increased risk of bleeding associated with warfarin use, or because fewer patients with atrial fibrillation underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, the under-utilization of other effective cardiac medications in hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation remains a perplexing but reproducible finding.20 Warfarin and amiodarone were commonly used among patients with atrial fibrillation, reflecting the established efficacy of these agents in the treatment of atrial fibrillation.28 It should be noted, however, that rates of warfarin prescription were lower in our study than has been reported in other studies.29 This finding may be secondary to provider reluctance to prescribe dual-antiplatelet therapy plus warfarin due to concerns about an increased risk for major bleeding episodes.30

Despite the fact that a greater proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, patients with any type of atrial fibrillation were less likely than patients who did not have this arrhythmia to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention. In keeping with their higher disease acuity and poorer overall clinical status, patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation were more likely to have undergone thrombolysis, placement of an Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, and permanent pacemaker implantation. Our findings suggest that opportunities exist for enhanced prevention of atrial fibrillation and its complications through better application of evidence-based in-hospital acute coronary syndrome treatments.

In-Hospital Complications and Thirty-Day Mortality

As has been reported in other community-based studies of hospitalized patients with an acute coronary syndrome,28 including a more limited analysis involving GRACE participants, patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation were twice as likely to die during hospitalization than were patients who did not develop atrial fibrillation.20,27 The relationship between new-onset atrial fibrillation, stroke, and left ventricular dysfunction likely explains a great deal of the association between atrial fibrillation and increased in-hospital mortality among GRACE participants. No excess 30-day mortality was noted among patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation compared to acute coronary syndrome patients without atrial fibrillation. This finding could be due to a healthy survivor effect or because of a lack of power. In contrast to the findings of a prior study,16 patients with pre-existing atrial fibrillation and an acute coronary syndrome were 30% more likely to die while hospitalized, and 40% more likely to have died by 30-days after hospital discharge, than patients without atrial fibrillation. Since atrial fibrillation occurring in the community is associated with duration and severity of exposure to cardiovascular risk factors, the observed relation between pre-existing atrial fibrillation and increased short-term mortality rates likely reflects the more advanced age and greater risk factor burden of patients with a recent or long-standing history of atrial fibrillation.

Trends in Major Hospital Complications in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

Although the incidence rates of in-hospital stroke did not decline in patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation during the years under study, the rates of all other major in-hospital complications, including death, declined in patients with pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation between 2000 and 2007. These findings likely reflect the enhanced monitoring and treatment of hospitalized patients with an acute coronary syndrome in addition to the better and timelier treatment of atrial fibrillation in GRACE participants over time.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include its large and diverse sample of patients hospitalized with validated acute coronary syndrome in multiple nations and its relatively contemporary perspective into the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndrome. As an observational, non-randomized investigation, however, GRACE is subject to certain limitations, including missing information as well as potential confounding by treatment indication or other unmeasured factors. Associations in a large sample such as this one may be statistically significant but not clinically meaningful. The study sample is restricted to patients with atrial fibrillation and hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome and findings may differ in patients with atrial fibrillation in the community. Patients who died before reaching study hospitals were excluded, left ventricular systolic function was measured in less than one-half of study participants, prescription of anti-arrhythmic drugs used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation was not collected, and timing of atrial fibrillation in relation to myocardial injury or receipt of cardiac medications as well as coronary reperfusion was not recorded.

Conclusions

In this large multinational study, atrial fibrillation was a common and serious complication in patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome. We observed encouraging declines in the incidence and prevalence rates of atrial fibrillation, likely reflecting enhanced treatment efforts. Nevertheless, pre-existing and new-onset atrial fibrillation remained associated with an increased risk of important cardiovascular, renal, and bleeding complications, as well as increased in-hospital mortality. Efforts remain warranted to improve the primary and secondary prevention of all patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome, but particularly among those with pre-existing atrial fibrillation and groups identified in this study as being at high risk for new-onset atrial fibrillation.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the assistance of the many nurses and physicians who participated in GRACE. Further information about the GRACE project, along with a list of participants, is available at www.outcomes.org/grace.

Funding Sources:

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from Sanofi Aventis to the Center for Outcomes Research, University of Massachusetts Medical School. Partial salary support is additionally provided by National Institute of Health grants 1U01HL105268-01 (DDM, RJG, JSS, JMG), KL2RR031981 (DDM) and K01AG33643 (JSS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114:119–125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizzetti F, Turazza FM, Franzosi MG, et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: the GISSI-3 data. Heart. 2001;86:527–532. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.5.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saczynski JS, McManus D, Zhou Z, et al. Trends in atrial fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crenshaw BS, Ward SR, Granger CB, et al. Atrial fibrillation in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: the GUSTO-I experience. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:406–413. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helmers C, Lundman T, Mogensen L, et al. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction. Acta Med Scand. 1973;193:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1973.tb10535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakata K, Kurihara H, Iwamori K, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:1522–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eldar M, Canetti M, Rotstein Z, et al. Behar S. Significance of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation complicating acute myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era. SPRINT and Thrombolytic Survey Groups. Circulation. 1998;97:965–970. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jewitt DE, Balcon R, Raftery EB, Oram S. Incidence and management of supraventirucular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1969;77:290–293. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liberthson RR, Salisbury KW, Hutter AM, Jr, DeSanctis RW. Atrial tachyarrhythmias in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1976;60:956–960. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luria MH, Knoke JD, Wachs JS, Luria MA. Survival after recovery from acute myocardial infarction. Two and five year prognostic indices. Am J Med. 1979;67:7–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madias JE, Patel DC, Singh D. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study based on data from a consecutive series of patients admitted to the coronary care unit. Clin Cardiol. 1996;19:180–186. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960190309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg RJ, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, et al. Recent trends in the incidence rates of and death rates from atrial fibrillation complicating initial acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J. 2002;143:519–527. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong CK, White HD, Wilcox RG, et al. New atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial infarction independently predicts death: the GUSTO-III experience. Am Heart J. 2000;140:878–885. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.111108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong CK, White HD, Wilcox RG, et al. Significance of atrial fibrillation during acute myocardial infarction, and its current management: insights from the GUSTO-3 trial. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2003;7:201–207. doi: 10.1023/B:CEPR.0000012382.81986.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau DH, Huynh LT, Chew DP, et al. Prognostic impact of types of atrial fibrillation in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, et al. A 30-year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, et al. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1162–1168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cristal N, Peterburg I, Szwarcberg J. Atrial fibrillation developing in the acute phase of myocardial infarction. Prognostic implications. Chest. 1976;70:8–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.70.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta RH, Dabbous OH, Granger CB, et al. Comparison of outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes with and without atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rationale and design of the GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) Project: a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2001;141:190–199. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.112404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Avezum A, et al. Practice variation and missed opportunities for reperfusion in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Lancet. 2002;359:373–377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steg PG, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, et al. Baseline characteristics, management practices, and in-hospital outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute coronary syndromes in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitt J, Duray G, Gersh BJ, Hohnloser SH. Atrial fibrillation in acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review of the incidence, clinical features and prognostic implications. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1038–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsang TS, Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ. Epidemiological profile of atrial fibrillation: a contemporary perspective. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopes RD, Pieper KS, Horton JR, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes following atrial fibrillation in patients with acute coronary syndromes with or without ST-segment elevation. Heart. 2008;94:867–873. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jabre P, Roger VL, Murad MH, et al. Mortality associated with atrial fibrillation in patients with myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2011;123:1587–1593. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh P, Arrevad PS, Peterson GM, Bereznicki LR. Evaluation of antithrombotic usage for atrial fibrillation in aged care facilities. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36:166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal S, Bennett D, Smith DJ. Predictors of warfarin use in atrial fibrillation patients in the inpatient setting. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2010;10:37–48. doi: 10.2165/11318870-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]