Abstract

Study Objective:

Several studies have suggested that hypocretin-1 may influence the cerebral control of the cardiovascular system. We analyzed whether hypocretin-1 deficiency in narcolepsy patients may result in a reduced heart rate response.

Design:

We analyzed the heart rate response during various sleep stages from a 1-night polysomnography in patients with narcolepsy and healthy controls. The narcolepsy group was subdivided by the presence of +/− cataplexy and +/− hypocretin-1 deficiency.

Setting:

Sleep laboratory studies conducted from 2001-2011.

Participants:

In total 67 narcolepsy patients and 22 control subjects were included in the study. Cataplexy was present in 46 patients and hypocretin-1 deficiency in 38 patients.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Results:

All patients with narcolepsy had a significantly reduced heart rate response associated with arousals and leg movements (P < 0.05). Heart rate response associated with arousals was significantly lower in the hypocretin-1 deficiency and cataplexy groups compared with patients with normal hypocretin-1 levels (P < 0.04) and patients without cataplexy (P < 0.04). Only hypocretin-1 deficiency significantly predicted the heart rate response associated with arousals in both REM and non-REM in a multivariate linear regression.

Conclusions:

Our results show that autonomic dysfunction is part of the narcoleptic phenotype, and that hypocretin-1 deficiency is the primary predictor of this dysfunction. This finding suggests that the hypocretin system participates in the modulation of cardiovascular function at rest.

Citation:

Sorensen GL; Knudsen S; Petersen ER; Kempfner J; Gammeltoft S; Sorensen HBD; Jennum P. Attenuated heart rate response is associated with hypocretin deficiency in patients with narcolepsy. SLEEP 2013;36(1):91–98.

Keywords: Arousal, autonomic dysfunction, heart rate response, hypocretin-1, narcolepsy

INTRODUCTION

Narcolepsy is a neurologic disease affecting one in 2,000 individuals. It is characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and early onset of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The disease is closely associated with low levels of hypocretin-1 (hcrt-1) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), especially in the two-thirds of patients with cataplexy (muscle weakness triggered by emotions).1 The neuropeptides hcrt-1 and hcrt-2 are produced and co-released by neurons in the lateral posterior hypothalamus of the brain, which project widely within the central nervous system (CNS).2 Animal studies have suggested that hcrt-1 may affect neuronal circuits that control the cardiovascular system,3–6 as exemplified by intrathecal hypocretin administration resulting in increased blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) mediated by enhancement of the sympathetic output.4,6

Two smaller human studies of patients with hcrt-1-deficient narcolepsy with cataplexy (NC) found contradictory results of sympathetic tone during daytime wakefulness.7,8 However, during sleep, reduced HR and sympathetic tone were found in NC patients of unknown hcrt-1 status,9,10 supporting the results of the animal studies.

We speculated that hcrt-1 deficiency is the main predictor/cause of autonomic dysfunction during sleep in patients with narcolepsy. We therefore measured the HR response at night in REM sleep and non-REM sleep in patients with narcolepsy +/− hcrt-1 deficiency and +/− cataplexy compared with healthy, age-matched controls.

METHOD

Subjects

Over a 10-year period (2001-2011), patients with narcolepsy seen at the Danish Center for Sleep Medicine, Glostrup University Hospital, were identified and consecutively included after ethical approval (KA03119) and written informed consent had been obtained. All patients fulfilled the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2) criteria for narcolepsy11 and were evaluated by neurologic examination, determination of routine blood characteristics, polysomnography (PSG), the multiple sleep latency test, and determination of CSF hcrt-1. The hypocretin measurement protocol and definition of hcrt-1 deficiency used were as previously published.1 Exclusion criteria were: additional neurologic, psychiatric, and cardiovascular disorders, and an apnea index > 5/h. All patients (except three with severe cataplexy) were free of antidepressants and stimulants 7-14 days before inclusion; 44 of 67 were completely drug-naïve (i.e., they had never taken medication).

In total, 81 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria, although because HR response is known to be age-related,12 14 patients were excluded to enable accurate age-matching of the narcolepsy groups. Of the excluded group, 12 of 14 had cataplexy and 10 of 13 had hcrt-1 deficiency. Thus, 67 patients with narcolepsy were included in the study, along with 22 healthy controls matched for age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). The control subjects were recruited by advertising for normal volunteers. None of the control subjects had any history of neurologic or sleep disorders, and their PSGs were evaluated by a neurologist as being normal.

Cataplexy was present in 46 of 67 patients and hcrt-1 deficiency was present in 38 of 61 patients. Six patients (five of six with cataplexy) refused lumbar puncture. Normal hcrt-1 levels were present in nine of 46 patients with cataplexy, and hcrt-1 deficiency was present in five of 21 patients without cataplexy.

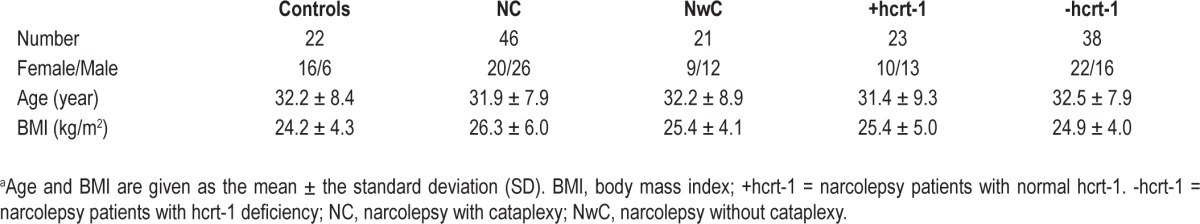

Demographic data of patient and control subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study patientsa

PSG Recordings

All subjects underwent 1 night of PSG recording consisting of electroencephalography (C3-A2, C4-A1), vertical and horizontal electrooculography (EOG), surface electromyography (EMG) of the submentalis and anterior muscles, electrocardiography (ECG), nasal air flow, thoracic respiratory effort, and oxygen saturation. Subjects were instructed not to consume any caffeinated or alcoholic drinks for at least 6 hours before the recordings were made.

Sleep stages, leg movements (LM), and arousals from sleep were manually scored according to standard criteria.13,14 The raw sleep data, hypnograms, and sleep events were extracted from Nervus® (V5.5, Cephalon DK, Nørresundby, Denmark) or Somnologica Studio® (V5.1, Embla, Broomfield, CO USA), using the built-in export data tool, and imported to the Matlab® analysis program (R2009b, The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) for further processing.

Data Analysis

The HR response was estimated as the area under the curve (AUC) describing the HR change associated with arousals and the HR change associated with isolated LM (separated from arousals). For each sleep event (arousal or LM), a signal segment was extracted from the ECG signal and QRS complexes were automatically detected using a self-implemented version of the Pan-Tompkins QRS-detector15 in Matlab. The intervals between QRS complexes (RR intervals) were calculated as the interbeat interval between successive R waves.

Before the HR was calculated, a manual noise analysis excluded any ECG signal segments contaminated with too much noise, because the detection of QRS complexes (and R waves) in these signal segments was impossible to validate. Therefore, not all scored arousals and LMs were included in the calculation of the HR response.

For every selected sleep event, the HR was analyzed for 10 heartbeats before and for 15 heartbeats after the onset of the event. Previous studies of HR response to arousal or motor activity had shown that the HR started to rise two heartbeats before the event.16,17 Therefore, a baseline value of HR was calculated by averaging the first seven beats of the 10 before the event. To determine the change in HR, this baseline value was subtracted from every HR from 10 beats before to 15 beats after the event.

For each subject, the change in HR was calculated for every event (separately for arousals and LM), and the average HR change was calculated from the mean of the 25 heartbeats related to each event. Thus, a curve was created displaying the HR change for each beat before and after the onset of the event, and the HR response was calculated as the AUC. By averaging individual HR responses, the HR response associated with arousals (HRRA) and the HR response associated with LM (HRRL) were obtained for each group. This was calculated both for events from all non-REM 2 sleep stages and events solely from REM sleep stages. Analysis of HR in non-REM 1 and 3 sleep stages was not possible in most subjects due to the insufficient amount of arousals/LM, and these were therefore omitted from this study.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the baseline HR (the average HR of the first seven of the 10 beats before event onset) and the HR response between groups, t-tests were performed. Univariate and backward stepwise multivariate linear regression were performed to determine the relationship between HR response and age, sex, BMI, disease-duration, disease-onset, +/− previous anticataplexy medication, +/− cataplexy, and +/− hcrt-1 status (Table 2). The +/− anticataplexy medication indicates whether patients were pausing with medication or had never been taking medication before inclusion (drug-naïve).

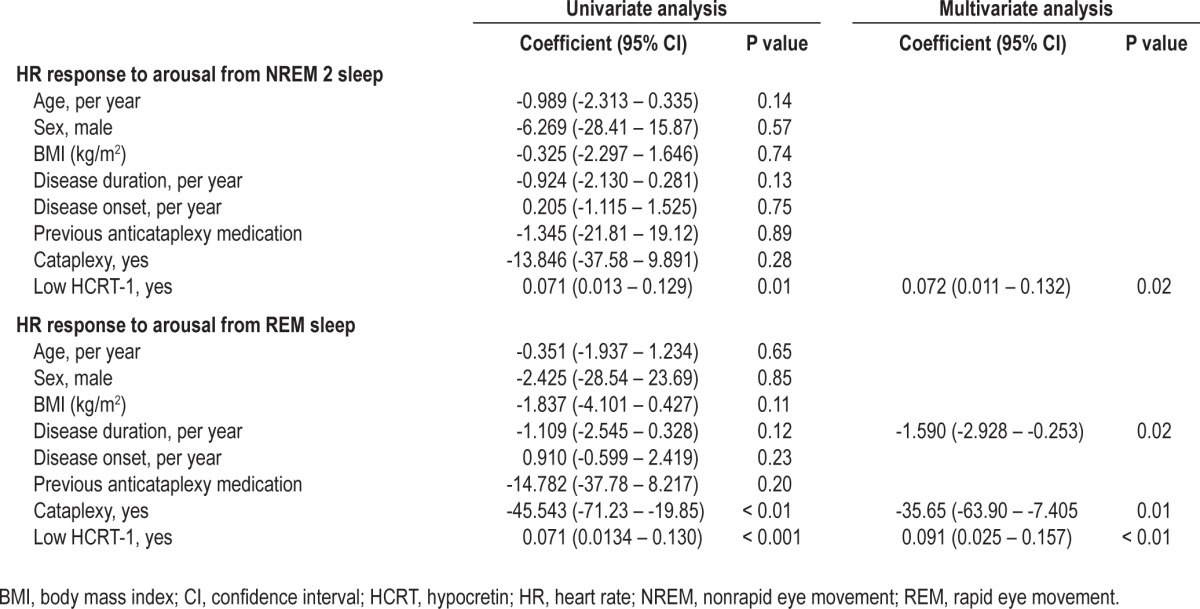

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis of HR response and demographic variables

PSG variables were measured for each subject. These included: sleep latency (SL), total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE), time from sleep onset to first epoch of REM sleep (REM SL), and percentage of stages 1, 2, and 3 non-REM and REM sleep. To evaluate between-group differences, each variable was log-transformed and two-sided t-tests were calculated for each variable for each of the three patient groups compared with the control group (Table 3). A Bonferroni correction was performed to take into account the problem of multiple comparisons.

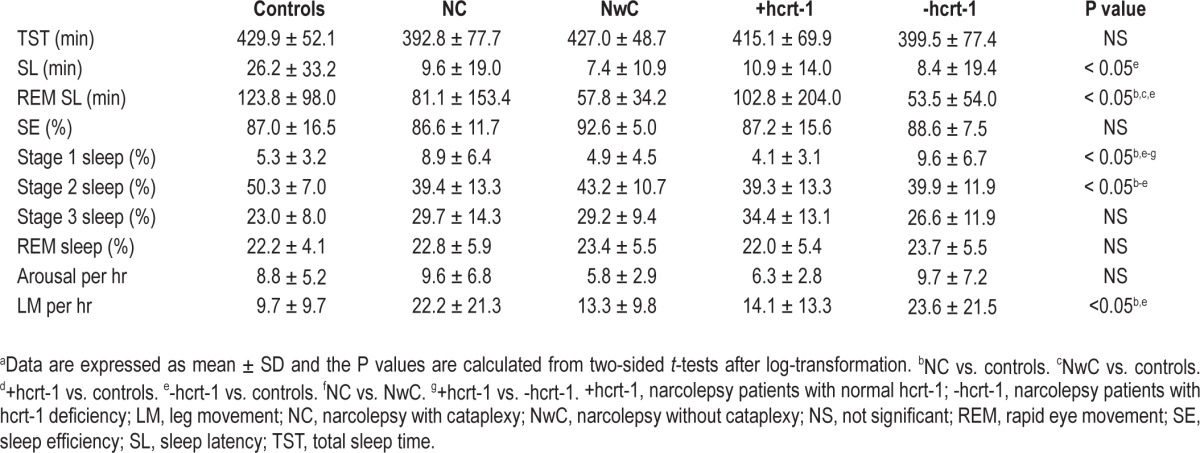

Table 3.

Comparison of PSG variablesa

A significance level of 0.05 is used in all statistical tests.

RESULTS

PSG Variables

The sleep parameters are presented in Table 3. All narcolepsy groups had a lower percentage stage 2 non-REM sleep compared with the control group. NC and narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency groups had a higher percentage stage 1 sleep compared with the control group, patients with narcolepsy without cataplexy (NwC), and those with normal hcrt-1. Furthermore, the REM SL was significantly lower for all patients with narcolepsy than for the controls, except for narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1. SL was only significantly lower for the narcolepsy patients with hcrt-1 deficiency.

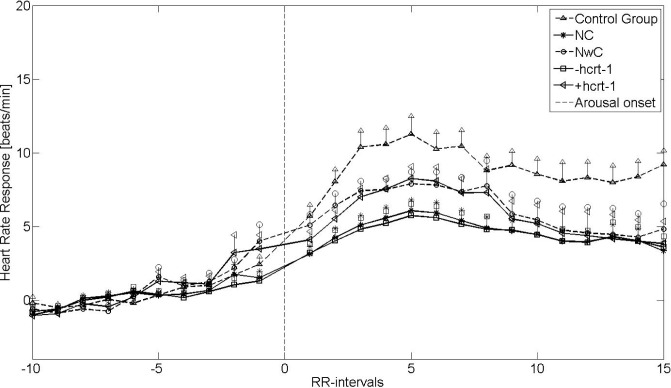

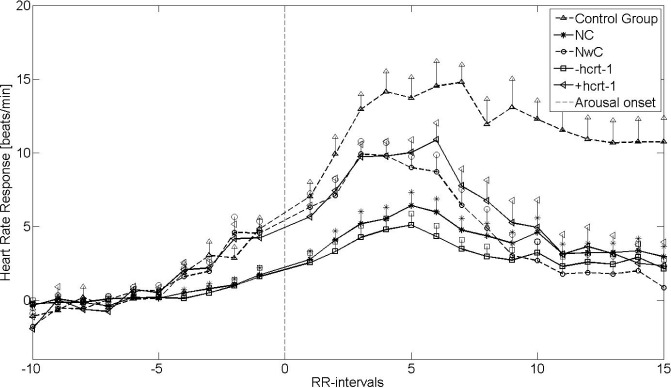

Heart Rate Response to Arousals

Figures 1 and 2 show the mean HRRA from non-REM sleep stage 2 and REM sleep, respectively. The vertical lines indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). The HR after arousal onset was accelerated in a similar way for patients with narcolepsy and controls, although to a lesser degree for the narcolepsy groups. The HRRA was significantly reduced for NC (P < 0.02) and for patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency (P < 0.01) compared with the controls in both REM and non-REM 2 sleep. Furthermore, in REM and non-REM 2 sleep, patients with cataplexy and patients with hcrt-1 deficiency had significantly lower HRRA than did those with NwC (P < 0.04) and narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1 (P < 0.04). Likewise, the HRRA for the NwC patients and the patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1 had a lower, although non-significant HRRA compared with controls (P = 0.10 and P = 0.09, respectively), placing them between the control group and NC and narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency groups. The baseline HR was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated for all narcolepsy groups except NwC patients compared with the controls. There was no difference in the baseline HR within the narcolepsy group.

Figure 1.

Heart rate response associated with arousals from non-rapid eye movement 2 sleep stages. +hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1; -hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency; NC, narcolepsy with cataplexy; NwC, narcolepsy without cataplexy; RR-intervals, intervals between successive QRS complexes.

Figure 2.

Heart rate response associated with arousals from rapid eye movement (REM) sleep stages. +hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1; -hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency; NC, narcolepsy with cataplexy; NwC, narcolepsy without cataplexy; RR-intervals, intervals between successive QRS complexes.

Table 2 shows the results for the univariate and multivariate backward stepwise linear regression analysis. In the univariate model, hcrt-1 deficiency was the only predictor of HRRA in non-REM 2 sleep stages (P = 0.01), whereas both cataplexy (P < 0.01) and hcrt-1 deficiency (P < 0.001) were predictors of the HRRA in REM sleep stages. In the multivariate analysis, the HRRA in REM sleep was predicted by disease duration (P = 0.02), hcrt-1 deficiency (P < 0.01), and cataplexy status (P = 0.01), but only by hcrt-1 deficiency in non-REM 2 sleep (P = 0.02).

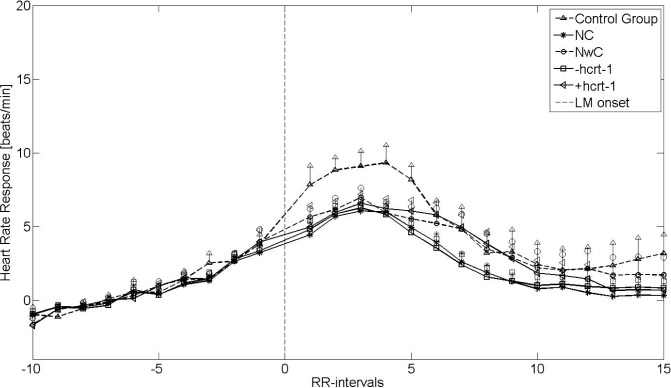

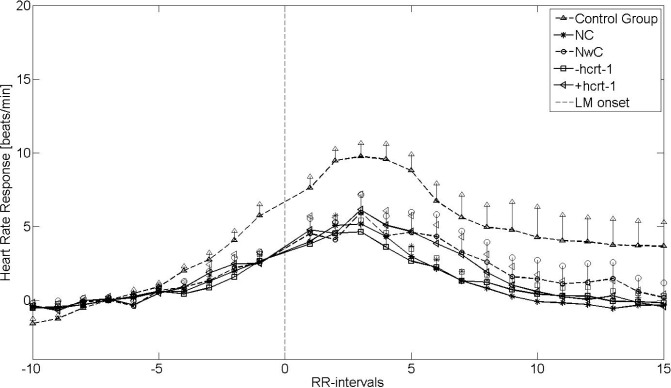

Heart Rate Response to LM

Figures 3 and 4 show the HRRL during non-REM 2 sleep and REM sleep, respectively. The vertical lines indicate the SEM. Four of 67 patients with narcolepsy (three of four with cataplexy and two of three with hcrt-1 deficiency; CSF not available in one of four) were excluded from further analysis due to noisy EMG signals. Furthermore, eight of 22 controls and 10 of 63 patients (seven with and three without cataplexy) with narcolepsy were excluded from the REM analysis due to insufficient numbers of LM during REM sleep.

Figure 3.

Heart rate response associated with leg movement (LM) from nonrapid eye movement (non-REM) 2 sleep stages. +hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1; -hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency; NC, narcolepsy with cataplexy; NwC, narcolepsy without cataplexy; RR-intervals, intervals between successive QRS complexes.

Figure 4.

Heart rate response associated with leg movement (LM) from rapid eye movement sleep stages. +hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1; -hcrt-1, patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency; NC, narcolepsy with cataplexy; NwC, narcolepsy without cataplexy; RR-intervals, intervals between successive QRS complexes.

With respect to HRRA, patients with narcolepsy and controls both had an increased HRRL, but to a significantly lesser degree in the narcolepsy groups (P < 0.05). However, unlike the HRRA, the HRRL did not differ within the narcolepsy groups, when the cataplexy and hcrt-1 groups were analyzed separately. This was confirmed by the univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis, in which none of the parameters was significant (data not shown). The baseline HR was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated for all narcolepsy groups, except the NwC group, compared with the controls. There was no difference in baseline HR within the narcolepsy groups.

DISCUSSION

This study shows for the first time that a reduced autonomic response to arousals in patients with narcolepsy is primarily predicted by hcrt-1 deficiency in both REM and non-REM sleep, independent of cataplexy and other factors. The data confirm that hcrt-1 deficiency has a great effect on the autonomic nervous system of patients with narcolepsy and that the hypocretin system is important for proper HR modulation at rest.

Cataplexy and hcrt-1 status both significantly predicted HRRA in REM sleep, although only hcrt-1 status remained significant in non-REM 2 sleep. None of the possible biasing factors (age, sex, BMI, disease duration, disease onset, anti-cataplexy medication) predicted HRRA in both non-REM and REM.

Our results are in accordance with the findings of reduced HR response associated with periodic limb movement (PLM) with and without arousals during non-REM 2 sleep in 14 HLA-DQB1*0602-positive (and presumed hcrt-1-deficient) NC patients.9 The Dauvilliers study design, which is comparable to ours, analyzed the HR response beat by beat only for PLM with and without arousals during non-REM 2 sleep, and found a significantly lower amplitude of tachycardia and bradycardia after onset of PLM, although the hcrt-1 level of the patients was not known, but they were presumed hcrt-1 deficient.9 In our study we used LM instead of PLM to ensure that the HR was stable and unaffected by other events before the onset of LM. Furthermore, in 18/22 control subjects, not enough (or even none) PLM were available for a valid statistical analysais. In addition, in some of the patients with narcolepsy not enough PLM were available.

Although the HRRL did not differ within the narcolepsy groups, the HRRL was significantly reduced compared with the control group both in REM and non-REM 2 sleep. A previous study has found hypocretin deficiency to be independently associated with the prevalence of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) during REM sleep in narcolepsy.18 Therefore, the LM in REM sleep may reflect underlying RBD in the narcolepsy patients.

Three studies have investigated the heart rate variability (HRV) in patients with narcolepsy using power spectrum analysis (PSA) and obtained very different results.7,8,10 Fronczek et al.7 found a higher power in all frequency bands in 15 hcrt-deficient NC patients. In contrast, normal cardiovascular changes during head-up tilt tests, the Valsalva manoeuvre, deep breathing, isometric handgrip, and cold face tests, but an increased sympathetic drive on HR at supine rest was found in 10 NC patients (nine of 10 with hcrt-1 deficiency),8 and an increase in HRV and sympathetic activity using PSA was found in NC patients of unknown hcrt-1 status,10 indicating normal and increased sympathetic tones, respectively. The latter study also reported an increased low/high frequency ratio during wakefulness before sleep, suggesting an altered circadian autonomic function in patients with narcolepsy patients. Although the study by Ferini-Strambi et al.10 was performed with sleeping patients with NC, the results are difficult to compare with ours because of the different study designs.

The great variability of these results may be due to the different study designs (day/night and measurement methods), small populations, and inadequate knowledge of the hcrt-1 level. Furthermore, as hypothesized by Grimaldi et al.,8 patients with narcolepsy may be highly vigilant during the daytime, when they are continuously fighting against sleepiness, which might imply stronger daytime sympathetic activation and thereby explain the different results obtained in previous studies. A single autonomic test during wakefulness may be insufficient in patients with narcolepsy.

Our results of intermediate low HRRA in narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1 indicate that this group could resemble a partially hcrt-1-deficient phenotype, as found in a postmortem study.19

Hypocretin neurons and receptors have been proposed as providing a link between central mechanisms that regulate arousal and sleep–wakefulness states and central control of autonomic functions,20 including parasympathetic cardiac activity.21 Hypocretin fibers have been found in nuclei that are well known to be involved in cardiovascular regulation, and it has been shown that hcrt-1 diminishes parasympathetic cardiac activity and thereby contributes to HR acceleration.21 Also, hypocretin acting on neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus is known to increase cardiovascular response.22

Chronic lack of hypocretin signalling may have consequences for cardiovascular function, which may be revealed in the HR and BP.23 However, hcrt-1-deficient patients with narcolepsy in our study not only had an elevated baseline HR but also failed to increase their HR in response to arousals or LM. This may be explained by two separate mechanisms: patients with hypocretin deficiency had increased arousability, sleep stage shift and daytime somnolence, which may affect autonomic activity; and the hypocretin system may directly influence autonomic activity on its own. The attenuated HR response may be explained by the already elevated HR in these patients, their impaired hypocretin signalling, or by both factors. Hcrt-1 fibers have been found in the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus, which elicits an inhibitory pathway to preganglionic cardiac vagal neurons.21 The hcrt-1 deficiency may cause this pathway to be impaired and parasympathetic activity would explain the attenuated HR response. This further supports the hypothesis that the normal hcrt-1 group could be a partially hcrt-1-deficient phenotype. These patients therefore also show an attenuated HR response due to impaired hypocretin signalling. To date, there have been few post-mortem studies of hypocretin-deficient patients,19,24 and currently there is no evidence of neurodegeneration of systems other than the hypocretin neurons.

Consequently, we believe that the changes in autonomic function observed here reflect stage-dependent dynamic changes in autonomic activity, which could explain the differences between the findings of our study and those of others evaluating autonomic activity during wakefulness. This is in contrast to the abnormalities observed in Parkinson’s Disease (PD) patients who also show attenuated HRRA/HRRL,25 but this is probably due to the destruction of neurons and nuclei in multiple brain areas involving the autonomic systems.26

The limitation of the study is that the autonomic test used herein has not previously been validated by comparison with other autonomic tests. HR in wakefulness and sleep is controlled by sympathetic and parasympathetic activity in mutual balance. The autonomic function is primarily tested with the head-up tilt test, the Valsalva maneuver, deep breathing, etc. During arousal there is likely an activation of the sympathetic system due to HR increase. Our study was performed during sleep, ensuring that natural conditions were present for studying neural modulation of the cardiovascular system. Future studies imply comparison of arousal and LM HR activation with other autonomic tests.

The AUC used in the current study is a simple, robust measure of HR response that allows a straightforward comparison of various groups instead of a beat-by-beat analysis with many comparisons. The AUC also allowed us to do univariate and multivariate regression analyses that took into account the influence of several confounder variables.

Future analysis could include comparisons of HR response from patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency and without cataplexy with that of patients with narcolepsy with normal hcrt-1 and with cataplexy.

We conclude that patients with narcolepsy present autonomic deficits from arousals and locomotor activity during REM and non-REM 2 sleep, which indicates that there is a stage-dependent effect on the autonomic system. The attenuated HR response was greatest for patients with narcolepsy with hcrt-1 deficiency, which suggests that the hypocretinergic system plays an important role in the autonomic tone and modulation at rest.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knudsen S, Jennum P, Alving J, Sheikh SP, Gammeltoft S. Validation of the ICSD-2 Criteria for CSF hypocretin-1 measurements in the diagnosis of narcolepsy in the Danish population. Sleep. 2010;33:169–76. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, et al. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciriello J, de Oliveira CVR. Cardiac effects of hypocretin-1 in nucleus ambiguus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1611–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00719.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Oliveira CVR, Rosas-Arellano MP, Solano-Flores LP, Ciriello J. Cardiovascular effects of hypocretin-1 in nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1369–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00877.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samson WK, Gosnell B, Chang JK, Resch ZT, Murphy TC. Cardiovascular regulatory actions of the hypocretins in brain. Brain Res. 1999;831:248–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shirasaka T, Nakazato M, Matsukura S, Takasaki M, Kannan H. Sympathetic and cardiovascular actions of orexins in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1780–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.6.R1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fronczek R, Overeem S, Reijntjes R, Lammers GJ, van Dijk JG, Pijl H. Increased heart rate variability but normal resting metabolic rate in hypocretin/orexin-deficient human narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:248–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grimaldi D, Pierangeli G, Barletta G, et al. Spectral analysis of heart rate variability reveals an enhanced sympathetic activity in narcolepsy with cataplexy. Clin Neurophys. 2010;121:1142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauvilliers Y, Pennestri MH, Whittom S, Lanfranchi PA, Montplaisir JY. Autonomic response to periodic leg movements during sleep in narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep. 2011;34:219–23. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferini-Strambi L, Spera A, Oldani A, et al. Autonomic function in narcolepsy: power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. J Neurol. 1997;244:252–5. doi: 10.1007/s004150050080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD)-Diagnostic and Coding Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosselin N, Michaud M, Carrier J, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. Age difference in heart rate changes associated with micro-arousals in humans. Clin Neurophys. 2002;113:1517–21. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnet MH, Carley D, Guilleminault CG, et al. EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Quan SF. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan J, Tompkins WJ. A real-time QRS detection algorithm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1985;32:230–6. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1985.325532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fantini ML, Michaud M, Gosselin N, Lavigne G, Montplaisir J. Periodic leg movements in REM sleep behavior disorder and related autonomic and EEG activation. Neurology. 2002;59:1889–94. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038348.94399.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sforza E, Jouny C, Ibanez V. Cardiac activation during arousal in humans: further evidence for hierarchy in the arousal response. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1611–9. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knudsen S, Gammeltoft S, Jennum PJ. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder in patients with narcolepsy is associated with hypocretin-1 deficiency. Brain. 2010;133:568–79. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thannickal TC, Nienhuis R, Siegel JM. Localized loss of hypocretin (orexin) cells in narcolepsy without cataplexy. Sleep. 2009;32:993–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young JK, Wu M, Manaye KF, et al. Orexin stimulates breathing via medullary and spinal pathways. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1387–95. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00914.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dergacheva O, Philbin K, Batemana R, Mendelowitza D. Hypocretin-1 (orexin A) prevents the effects of hypoxia/hypercapnia and enhances the gabaergic pathway from the lateral paragigantocellular nucleus to cardiac vagal neurons in the nucleus ambiguus. Neuroscience. 2011;175:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirasaka T, Kunitake T, Takasaki M, Kannan H. Neuronal effects of orexins: relevant to sympathetic and cardiovascular functions. Regul Pept. 2002;104:91–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastianini S, Silvani A, Berteotti C, et al. Sleep related changes in blood pressure in hypocretin-deficient narcoleptic mice. Sleep. 2011;34:213–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, et al. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;6:991–7. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen GL, Kempfner J, Zoetmulder M, Sorensen HB, Jennum P. Attenuated heart rate response in REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27:888–94. doi: 10.1002/mds.25012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braak H, Tredici KD, Rb U, de Vos RAI, Jansen Steur ENH, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]