Abstract

The matching of muscle O2 delivery to O2 utilization can be inferred from the adjustments in muscle deoxygenation (Δ[HHb]) and pulmonary O2 uptake (V̇o2p). This study examined the adjustments of V̇o2p and Δ[HHb] during ramp incremental (RI) and constant-load (CL) exercise in adult males. Ten young adults (YA; age: 25 ± 5 yr) and nine older adults (OA; age: 70 ± 3 yr) completed two RI tests and six CL step transitions to a work rate (WR) corresponding to 1) 80% of the estimated lactate threshold (same relative WR) and 2) 50 W (same absolute WR). V̇o2p was measured breath by breath, and Δ[HHb] of the vastus lateralis was measured using near-infrared spectroscopy. Δ[HHb]-WR profiles were normalized from baseline (0%) to peak Δ[HHb] (100%) and fit using a sigmoid function. The sigmoid slope (d) was greater (P < 0.05) in OA (0.027 ± 0.01%/W) compared with YA (0.017 ± 0.01%/W), and the c/d value (a value corresponding to 50% of the amplitude) was smaller (P < 0.05) for OA (133 ± 40 W) than for YA (195 ± 51 W). No age-related differences in the sigmoid parameters were reported when WR was expressed as a percentage of peak WR. V̇o2p kinetics compared with Δ[HHb] kinetics for the 50-W transition were similar between YA and OA; however, Δ[HHb] kinetics during the transition to 80% of the lactate threshold were faster than V̇o2p kinetics in both groups. The greater reliance on O2 extraction displayed in OA during RI exercise suggests a lower O2 delivery-to-O2 utilization relationship at a given absolute WR compared with YA.

Keywords: older adults, near-infrared spectroscopy, sigmoid function

during transitions to constant-load (CL) moderate-intensity, or heavy-intensity exercise, pulmonary O2 uptake (V̇o2p) kinetics generally are slower in older adults (OA) compared with young adults (YA). The time constant (τ) for the fundamental component of the V̇o2p response (τV̇o2p), which is considered to reflect the adjustment of muscle O2 utilization (V̇o2m) and oxidative energy production during the transition to exercise (3, 24, 33), is ∼40–50 s in OA and ∼20–30 s in YA (2, 14, 15, 18, 27, 40, 55). Studies (14–16, 18, 27) from our laboratory combining measures of V̇o2p and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)-derived muscle deoxygenation (Δ[HHb]) have shown that during transitions to CL moderate-intensity or heavy-intensity exercise, despite slowed V̇o2p kinetics in OA compared with YA, overall muscle deoxygenation kinetics were generally similar to or faster than those for YA. In addition, the steady-state Δ[HHb]-to-ΔV̇o2p relationship was greater in OA than in YA (15, 16, 18, 27, 40). As the NIRS-derived Δ[HHb] signal reflects local muscle O2 extraction, and thus the ratio of local muscle O2 utilization to microvascular blood flow, these observations suggest that the adjustment of muscle blood flow, specifically microvascular blood flow, during transitions to CL exercise is attenuated in OA compared with YA, thus requiring increased O2 extraction to meet the muscle O2 requirement for mitochondrial oxidative ATP production. The reported slower heart rate (HR; reflecting central O2 delivery) (14–16, 18, 40) and leg (conduit artery) blood flow kinetics (18) as well as lower steady-state leg blood flow (36, 37, 46, 48, 50) and vascular conductance (36, 37, 46, 48, 50) in OA are consistent with an attenuated muscle blood flow response during transitions to and in the steady state of CL submaximal exercise. A consequence of slower adjustment in V̇o2m (as reflected by V̇o2p) in OA compared with YA is that, for a given ATP and O2 requirement, a greater O2 deficit and greater reliance on substrate-level phosphorylation are required, which would disrupt metabolic “stability” (25) and possibly compromise exercise tolerance in these individuals (25).

Unlike transitions to CL moderate-intensity and heavy-intensity exercise, where “steady-state” V̇o2p, V̇o2m, and muscle blood flow values eventually are achieved, this is not the case for ramp incremental (RI) exercise to the limit of tolerance. During RI exercise, V̇o2p (1, 13) and muscle blood flow (1, 49, 53) increase in an apparently linear fashion as work rate (WR) increases across a wide range of exercise intensities and ATP requirements, but with V̇o2m (and V̇o2p) lagging behind the actual muscle O2 requirement. For YA performing exercise transitions to CL exercise from low or raised baseline metabolic rates, the kinetics of V̇o2p (and V̇o2m) and limb (conduit artery) blood flow display dynamic nonlinearity across a range of increasing exercise intensities; the rate of adjustment of V̇o2p (and V̇o2m) (7, 31, 32, 38, 62, 63) and limb (conduit artery) blood flow become slower (38), the “steady-state” ΔV̇o2p -ΔWR relationship (V̇o2p gain) increases (7, 32, 38, 62, 63), and the “steady-state” Δmuscle blood flow-ΔV̇o2p relationship becomes smaller (38) with exercise transitions initiated from elevated baseline intensities. Similar nonlinear responses in V̇o2p kinetics and V̇o2p gain were also observed in OA when transitions to CL exercise were initiated from baseline metabolic rates representing lower and upper regions of the moderate-intensity domain (57). In YA performing RI exercise to the limit of tolerance, NIRS-derived muscle deoxygenation displays a nonlinear, sigmoidal pattern of increase, reflecting a nonlinear increase in muscle O2 extraction with increasing WR and V̇o2p (6, 20, 47), which is consistent with a changing (nonlinear) relationship between microvascular blood flow and V̇o2m throughout a range of exercise intensities. Given the slower V̇o2p and similar Δ[HHb] kinetics observed in OA compared with YA during transitions to CL moderate-intensity or heavy-intensity exercise, with a greater reliance on O2 extraction at any given V̇o2m, a greater muscle deoxygenation response might be expected in OA compared with YA during RI exercise where steady-state conditions are not achieved. An apparently greater submaximal Δ[HHb]-versus-WR relationship in OA compared with YA was reported by Ferri et al. (22) during step-incremental knee extension (increases of 20%, 40%, and 60% of one repetition maximum every 3 min) and step-incremental cycling exercise (increments of 10 and 20 W every minute for OA and YA, respectively) to exhaustion, although in that study, V̇o2p was not measured and detailed age- and WR-related comparisons of the Δ[HHb] profiles were not presented. Analysis of the adjustments of Δ[HHb] and V̇o2p adjustments would provide inferences regarding the matching between muscle O2 delivery and muscle O2 utilization during nonsteady-state conditions spanning a wide range of exercise domains from light- to very heavy (or severe)-intensity exercise.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the adjustments of V̇o2p and NIRS-derived leg muscle Δ[HHb] during nonsteady-state RI exercise to the limit of tolerance in OA and YA. Also, in the same subjects, responses were examined during transitions to steady-state CL moderate-intensity exercise of the same absolute intensity (i.e., 50 W) and the same relative intensity [i.e., 80% of the estimated lactate threshold (θL)]. We hypothesized that 1) the position of the sigmoid Δ[HHb]-WR response profile would be left shifted toward a lower WR in OA compared with YA and 2) the slope of the linear portion of the Δ[HHb]-WR relationship would be greater in OA compared with YA. Also, in agreement with previous findings at the same relative intensity, we hypothesized that 3) the rate of adjustment of V̇o2p would be slowed in OA compared with YA, but that the adjustment of Δ[HHb] would be similar, when exercise transitions were performed at the same absolute intensity (same WR, 50 W) and the same relative intensity (80% θL) within the moderate-intensity domain. Together, the findings would support the suggestion that adjustments of local muscle microvascular blood flow are attenuated in OA compared with YA, thereby requiring a greater reliance on O2 extraction to support oxidative ATP requirements.

METHODS

Subjects

Ten YA (age: 25 ± 5 yr, mean ± SD) and nine OA (age: 70 ± 3 yr, mean ± SD) men volunteered and gave written consent to participate in the study. All subjects were healthy, recreationally active, nonsmokers with no previously diagnosed respiratory, cardiovascular, metabolic, or musculoskeletal disease. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Subjects of The University of Western Ontario. A detailed written explanation of the experimental protocol was given to all subjects before they were tested. Additionally, subjects were not taking any medications that could affect their cardiorespiratory or metabolic responses to exercise. OA subjects were cleared for participation in the study after first undergoing a physician-supervised medical screening and an exercise stress test to the limit of tolerance before the investigation.

Protocol

All subjects performed two RI exercise tests to the limit of tolerance on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (H-3oc-R Lode; Lode, B.V., Groningen, The Netherlands); each test was separated by at least 48 h to allow recovery. The RI test began with 6 min of cycling at a light-intensity WR of 20-W baseline exercise, with a pedal cadence of 70–80 rpm, after which the WR increased linearly as a ramp function at a rate of 20 W/min until the subject could no longer maintain a cadence of 50 rpm. After each RI test, peak V̇o2p and the V̇o2p corresponding to θL were determined for each subject. Peak V̇o2p was determined as the average V̇o2p during the final 20 s of each RI test. θL was estimated using standard gas exchange and ventilatory indexes and was defined as the V̇o2p at which pulmonary CO2 output (V̇co2p) and expired minute ventilation (V̇e) began to increase out of proportion to the rise in V̇o2p. Additionally, there was a systematic rise in the ventilatory equivalent for V̇o2p (V̇e/V̇o2p) and end-tidal Po2, whereas the ventilatory equivalent for V̇co2p (V̇e/V̇co2p) and end-tidal Pco2 were stable. Based on the results from the RI tests, a WR was selected that would elicit a steady-state V̇o2p corresponding to ∼80% θL.

Subjects returned to the laboratory on several occasions to complete repetitions of CL step transitions to WRs within the moderate-intensity exercise domain. The step transitions consisted of 6 min of cycling at a baseline of 20 W followed by an instantaneous increase in WR to 1) an absolute WR of 50 W or 2) a relative WR corresponding to 80% θL, with each step transition lasting 6 min. Subjects completed six step transitions to both absolute and relative WRs, with conditions being randomly assigned. Only a single step transition was completed by YA on each testing day, whereas OA performed two step transitions on the same testing day (to decrease the number of visits for OA), with each transition separated by a 30-min period of resting recovery (sitting on a chair) to allow cardiovascular and metabolic variables to return back toward preexercise baseline conditions.

Measurements

Gas exchange measurements were similar to those previously described by Babcock et al. (2). Briefly, inspired and expired airflow and volumes were measured throughout the exercise protocol using a low-dead space (90 ml) bidirectional turbine (3.0 liters, Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO), which was calibrated before each test using a syringe of known volume. Inspired and expired gases were sampled continuously (every 20 ms) at the mouth and analyzed for the fractional concentrations of O2, CO2, and N2 by mass spectrometry (Innovision, AMIS 2000, Lindvedvej, Denmark) after calibration with precision-analyzed gas mixtures. Changes in gas concentrations were aligned with gas volumes by measuring the time delay (TD) for a square-wave bolus of gas passing the turbine to the resulting changes in fractional gas concentrations as measured by the mass spectrometer. The collected data were transferred to a computer, which aligned concentrations with volume information to build a profile of each breath. The algorithms of Beaver et al. (4) were used to calculate breath-by-breath alveolar gas exchange. Heart rate (HR) was continuously monitored by ECG using PowerLab (ML132/ML880, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) with a three-lead arrangement and recorded with LabChart (version 6.0, AD Instruments) on a separate computer.

Changes in the concentration of local Δ[HHb], oxy-, and total hemoglobin + myoglobin (with the absorbance spectra of hemoglobin and myoglobin being virtually indistinguishable within the NIR spectral range) of the vastus lateralis quadriceps muscle were measured continuously (sampling rate: 2 Hz) using NIRS (NIRO 300, Hamamatsu Photonics). Optodes were placed on the belly of the muscle midway between the lateral epicondyle and greater trochanter of the femur. Optodes were separated by 5 cm and housed in an optically dense rubber holder that was secured to the skin surface with tape and covered with an optically dense, black vinyl sheet, thus minimizing the intrusion of extraneous light. To further secure the position of the optodes during the exercise protocol, an elastic bandage was wrapped around the leg to prevent any movement of the optode assembly without restricting the range of motion of the leg during the cycling exercise. While subjects were at rest, before beginning any exercise, NIRS signals were monitored until steady-state baseline levels were established, at which time the signals were “zero set” such that further changes in the signal were reported as a change (Δ) from this relative “zero” baseline.

The physical principles of tissue spectroscopy and the manner in which these are applied have been previously explained by DeLorey et al. (17). Briefly, four laser diodes that produce different wavelengths (775, 810, 850, and 910 nm) are pulsed in rapid succession, and the NIR light produced by the diodes is transmitted through a fibre optic bundle to the tissue of interest. The transmitted light is returned through a separate fibre optic bundle and detected by a photomultiplier tube for online estimation and display of the concentration changes from the resting baseline values. As the differential path length in the quadriceps muscle at rest and during exercise is presently unknown, the NIRS-derived measures are reported in arbitrary units (AU). The raw attenuation signals were transferred and stored on a separate computer for later analysis.

Data Analysis

V̇o2p and HR data sets were edited for each individual trial by removing aberrant data that lay outside 4 SD of the local mean as they did not conform to a Gaussian distribution as previously described by Lamarra et al. (35). The data for each RI or CL transition were linearly interpolated on a second-by-second basis and time aligned to the onset of the RI or CL transition, labeled as time 0. The individual repetitions of RI and CL transitions were ensemble averaged to yield a single “average” profile for each subject and time averaged into 5-s bins.

The slope of the time-averaged V̇o2p-WR profiles for RI exercise [reflecting the functional V̇o2p gain (ΔV̇o2p/ΔWR)] were determined in YA and OA using linear regression analysis. The V̇o2p response was time aligned with the onset of RI exercise by shifting the V̇o2p profile data back by a calculated TD for each individual, as previously described by Davis et al. (12), to account for the delay in the rise of V̇o2p (a consequence of V̇o2p kinetics) relative to the increase in WR. Therefore, the left-shifted V̇o2p data were fit from the onset of RI exercise to a WR corresponding to ∼80% θL, thereby reflecting the linear V̇o2p-WR relationship within the moderate-intensity domain of the RI protocol.

CL on-transient responses for the 5-s averaged V̇o2p, Δ[HHb], and HR profiles were modeled using nonlinear regression analysis and a monoexponential model of the following form:

| (1) |

where Y(t) is V̇o2p at any time (t), YBsln is baseline V̇o2p during 20-W cycling before the step increase in WR, Amp is the steady-state increase in V̇o2p above the baseline value, and τ is the duration of time for V̇o2p to increase to 63% of the steady-state Amp. V̇o2p data were modeled from the phase 1 to phase 2 transition, determined as previously described by Rossiter et al. (54) and Gurd et al. (29), to the end of the exercise transition.

Beat-by-beat HR data were edited and averaged as described above for V̇o2p. The monoexponential model described in Eq. 1 was used to fit the on-transient HR response, with the TD constrained to time 0, such that the entire HR response from the onset to the end of the exercise was modeled.

Second-by-second NIRS-derived Δ[HHb] data were time aligned, ensemble averaged, and time averaged into 5-s bins to yield a single, averaged response for each subject in the RI and CL protocols. The Δ[HHb] profile for CL has been previously described to consist of a TD (TD-Δ[HHb]) at the onset of exercise followed by an increase in the Δ[HHb] signal that followed an “exponential-like” time course (17, 23). TD-Δ[HHb] was determined using second-by-second data and corresponded to the time, after the onset of exercise, at which the Δ[HHb] signal began to increase systematically above an early nadir value in the signal. TD-Δ[HHb] was determined for every CL trial and averaged to yield an average TD-Δ[HHb] for each subject. The time course for Δ[HHb] was modeled using an exponential function of the form described in Eq. 1 starting from the time corresponding to TD-Δ[HHb] and ending at a time corresponding to the beginning of the V̇o2p steady state (i.e., 5 × τV̇o2p). The time course for the increase in Δ[HHb] was described using the Δ[HHb] τ (τΔ[HHb]), whereas the overall time course of Δ[HHb] from the onset of moderate-intensity exercise was described using the “effective” τ (τΔ[HHb] = TD-Δ[HHb] +τΔ[HHb]).

During the RI exercise tests, Δ[HHb] data were normalized to the peak (calculated as a 5-s average) amplitude of the response. Baseline Δ[HHb] (0%) was established as the average steady state for the 20-W baseline cycling. The normalized Δ[HHb] response for both age groups during RI exercise was described as a function of 1) absolute WR (in W) and 2) relative WR (as a percentage of peak WR) and fit using a sigmoid model of the following form:

| (2) |

where F(x) is the normalized Δ[HHb] value at a given x value (e.g., WR), ƒ0 is the baseline, A is the total amplitude, c is a constant dependent on d, d is the slope of the sigmoid, and the c/d value is the x value corresponding to 50% of A. The sigmoid model has previously been shown, in young healthy adults, to provide a significantly better fit of the Δ[HHb]-WR response compared with a hyperbola model (6, 20).

Statistics

The dependent variables (V̇o2p, HR, and Δ[HHb]) were analyzed using unpaired t-tests and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Each analysis was performed using SPSS (version 17.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL). A significant F-ratio was identified using Fisher's least significant difference post hoc analysis, with statistical significance accepted at P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Nonsteady-State RI Exercise

V̇o2p response.

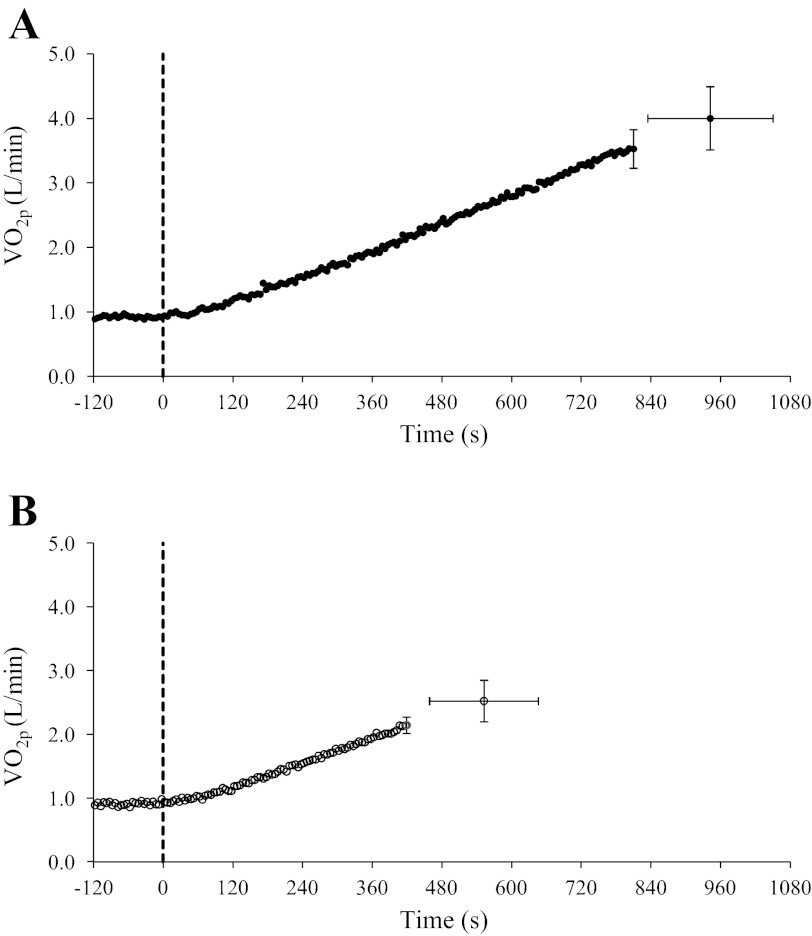

Subject characteristics and peak responses during RI exercise in YA and OA are shown in Table 1, and group mean V̇o2p response profiles during RI exercise are shown in Fig. 1. After an initial transient delay, V̇o2p increased linearly relative to time (and thus WR) (Fig. 1) in both YA (r = 0.89 ± 0.07) and OA (r = 0.76 ± 0.11). Absolute and relative peak V̇o2p were greater (P < 0.05) in YA (4.06 ± 0.43 l/min and 49 ± 5 ml·kg−1·min−1) compared with OA (2.63 ± 0.35 l/min and 30 ± 6 ml·kg−1·min−1; Table 1), a consequence of a greater (P < 0.05) peak WR in YA (338 ± 30 W) than in OA (215 ± 31 W; Table 1). Also, the V̇o2p corresponding to θL was greater (P < 0.05) in YA (2.3 ± 0.2 l/min) than in OA (1.6 ± 0.1 l/min; Table 1). During RI exercise, the functional gain (ΔV̇o2p/ΔWR) calculated for the V̇o2p-WR relationship (with WRs restricted to the moderate-intensity region of RI exercise) was greater (P < 0.05) in YA (10.0 ± 0.4 ml·min−1·W−1) than in OA (8.7 ± 1.2 ml·min−1·W−1); however, during CL exercise, the steady-state functional gain was not different between YA (9.5 ± 0.7 ml·min−1·W−1) and OA (9.9 ± 1.2 ml·min−1·W−1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and peak exercise responses

| V̇o2peak |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Age, yr | Body mass, kg | Body mass index, kg/m | In l/min | In ml·kg−1·min−1) | Peak WR, W | V̇o2p at θL, l/min | WR at 80% θL, W | |

| YA | 10 | 25 ± 5 | 84 ± 11 | 25 ± 3 | 4.06 ± 0.43 | 49 ± 5 | 338 ± 30 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 118 ± 25 |

| OA | 9 | 70 ± 3* | 88 ± 12 | 28 ± 3* | 2.63 ± 0.35* | 30 ± 6* | 215 ± 31* | 1.6 ± 0.1* | 64 ± 10* |

Values are means ± SD; n, subjects/group. YA, young adults; OA, older adults; V̇o2peak, peak O2 consumption; WR, work rate; V̇o2p, pulmonary O2 consumption; θL, estimated lactate threshold.

P < 0.05 compared with YA.

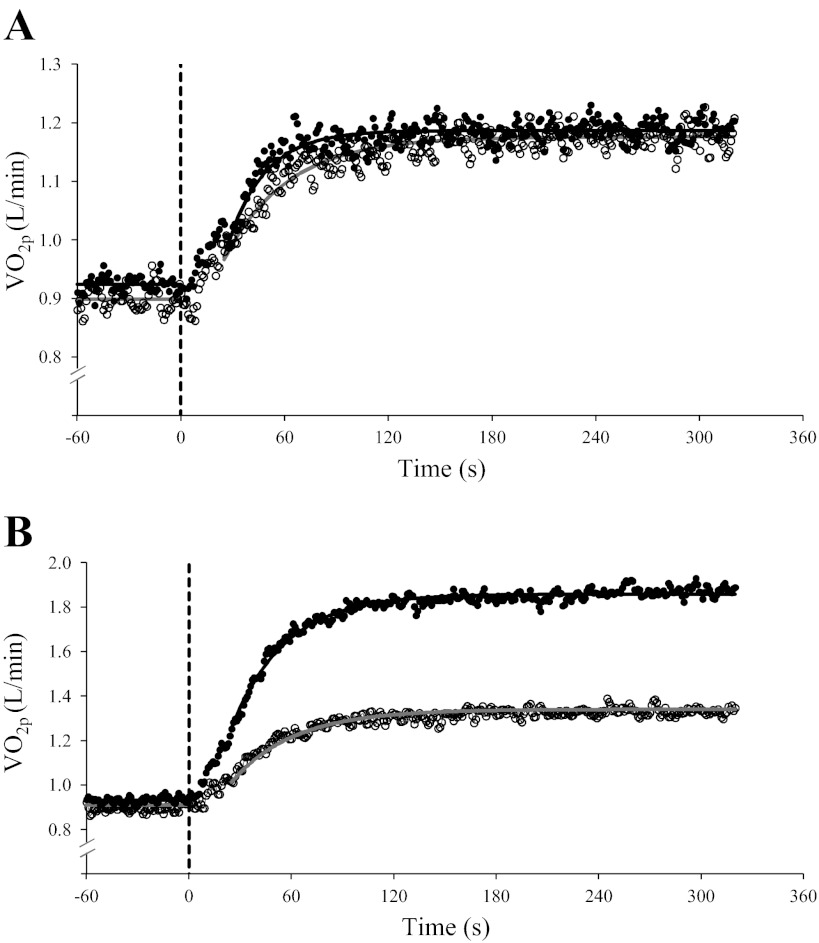

Fig. 1.

Group mean (±SD) pulmonary O2 consumption (V̇o2p) response profiles during ramp incremental (RI) exercise as a function of time (in s) for young adults (YA; A, ●) and older adults (OA; B, ○). Continuous curves represent mean values for all subjects; single points represent group mean (±SD) values at the point of fatigue during RI exercise. The dashed line indicates the onset of RI exercise.

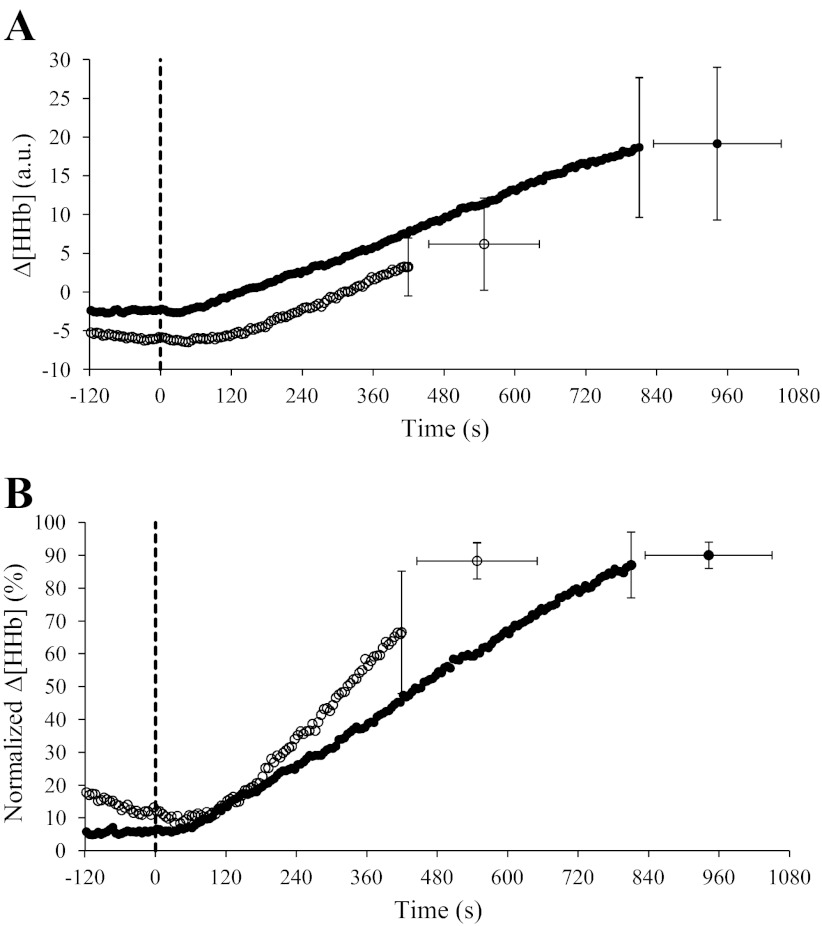

Δ[HHb] response.

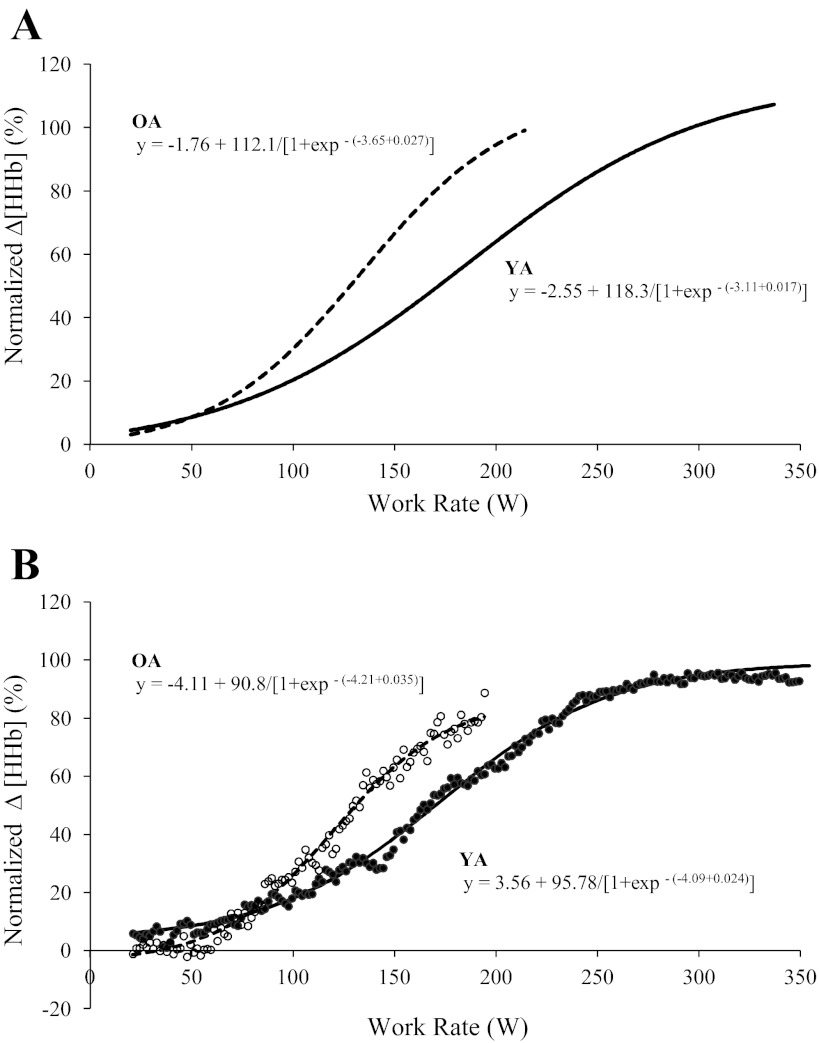

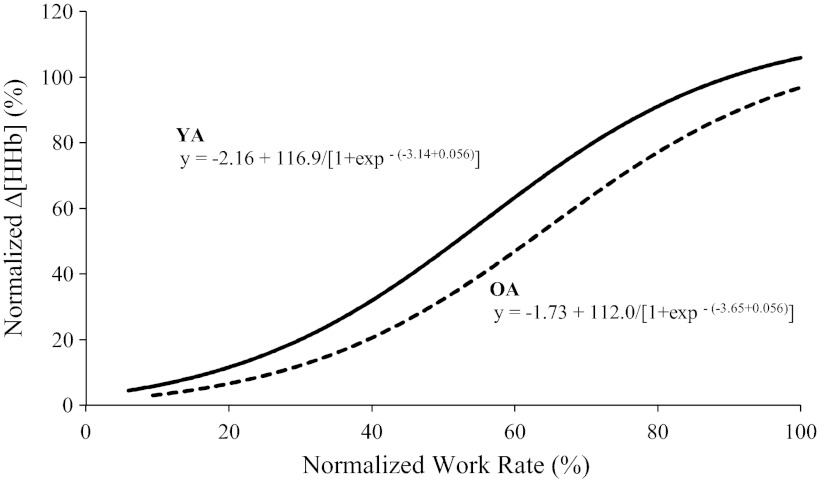

The group mean adjustment of Δ[HHb] during RI exercise in YA and OA groups is shown in Fig. 2A (absolute values) and Fig. 2B (normalized to the amplitude measured during RI exercise); Δ[HHb] data for one YA and three OA were removed due to poor quality during RI tests. The modeled sigmoid regression profile of the Δ[HHb]-WR response during RI exercise is shown for two age groups (Fig. 3A) and for a representative YA and OA (Fig. 3B), and the parameter estimates for Δ[HHb]-WR profiles during RI exercise for YA and OA are shown in Table 2. The slope of the Δ[HHb]-WR response was greater (P < 0.05) in OA (0.027 ± 0.01%/W) compared with YA (0.017 ± 0.01%/W), and the WR corresponding to 50% amplitude was lower (P < 0.05) in OA (133 ± 40 W) than in YA (195 ± 51 W; Fig. 3A and Table 2). No age-related differences were found for any of the sigmoid parameters when the relationship was expressed as a percentage of peak WR (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Group mean (±SD) absolute (A) and normalized (B; percentage of the peak amplitude during RI exercise) muscle deoxygenation (Δ[HHb]) response profiles to RI exercise in YA (●; n = 9) and OA (○; n = 6). Continuous curves represent mean values for all subjects; single points represent group mean (±SD) values at the point of fatigue during RI exercise. The dashed line indicates the onset of RI exercise.

Fig. 3.

Sigmoid models of normalized Δ[HHb] (percentage of the peak amplitude during RI exercise) as a function of absolute work rate (WR) for the group mean (A) and a representative subject (B) for YA (solid line, ●) and OA (dashed line, ○). The sigmoid models in A were recreated from the parameters shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates for normalized Δ[HHb] as a function of absolute and relative WRs during ramp incremental exercise in YA and OA

| YA | OA | |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute WR | ||

| ƒ0, % | −2.6 ± 7.1 | −1.8 ± 18.4 |

| A, % | 118 ± 20 | 112 ± 32 |

| d, %/W | 0.017 ± 0.01 | 0.027 ± 0.01* |

| c/d, W | 195 ± 51 | 133 ± 40* |

| Relative WR | ||

| ƒ0, % | −2.2 ± 7.3 | −1.7 ± 18.3 |

| A, % | 116 ± 19 | 112 ± 32 |

| d, %/%peak | 0.056 ± 0.02 | 0.056 ± 0.02 |

| c/d, %peak | 57.1 ± 9.5 | 64.1 ± 19.8 |

Values are means ± SD of the percentage of peak muscle deoxygenation (Δ[HHb]) during ramp incremental exercise as a function of absolute (in W) and relative (in %) WRs; n = 10 YA and 9 OA. ƒ0, baseline; A, amplitude; d, slope; c/d, WR corresponding to 50% of the total amplitude.

Significantly different from YA (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Sigmoid models of normalized Δ[HHb] (percentage of the peak amplitude during RI exercise) as a function of relative (percent peak) WR for the group mean for YA (solid line, ●) and OA (dashed line, ○). Sigmoid models were recreated from the parameters shown in Table 2.

Steady-State CL Exercise

V̇o2p kinetics.

The steady-state increase in V̇o2p (V̇o2p amplitude) for CL transitions to 50 W was similar in YA (0.26 ± 0.04 l/min) and OA (0.29 ± 0.03 l/min; Fig. 5A). During transitions to 80% θL, the V̇o2p amplitude was greater (P < 0.05) in YA (0.97 ± 0.27 l/min) than in OA (0.44 ± 0.12 l/min; Fig. 5B), reflecting the greater WR in YA (118 ± 25 W) than in OA (64 ± 10 W; Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Group mean absolute V̇o2p response profiles to 50 W (A) and 80% of the lactate threshold (θL; B) constant-load (CL) exercise in YA (●; n = 10) and OA (○; n = 9). The dashed line indicates the onset of CL exercise.

There were no age-related differences (age main effect, P = 0.093) in phase II τV̇o2p between YA and OA for transitions to an absolute WR of 50 W (Fig. 5A) and a relative WR of 80% θL (Fig. 5B); however, τV̇o2p was greater (intensity main effect, P < 0.05) for transitions to 80% θL than to 50 W (Table 3). There was a trend for an age × intensity interaction (P = 0.053), suggesting that in YA, τV̇o2p during the 50-W transition was less than τV̇o2p for the 80% θL transition and less than τV̇o2p for exercise transitions in OA (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for V̇o2p, HR, and Δ[HHb] kinetics during the “on” transition to constant-load, moderate-intensity exercise at 50 W and 80 % θL in YA and OA

| Phase II τV̇o2p, s | τHR, s | τΔ[HHb], s | TD-Δ[HHb], s | τ′Δ[HHb], s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 W | |||||

| YA | 22 ± 11 | 15 ± 8 | 12 ± 9 | 15 ± 3 | 27 ± 7 |

| OA | 38 ± 17 | 46 ± 32* | 15 ± 12 | 15 ± 2 | 30 ± 13 |

| 80% θL | |||||

| YA | 33 ± 11 | 25 ± 9† | 11 ± 4 | 10 ± 3† | 21 ± 6‡ |

| OA | 39 ± 17 | 41 ± 21* | 16 ± 10 | 13 ± 2* | 30 ± 10‡ |

Values are means ± SD. τ, Time constant of the response; HR, heart rate; TD, time delay; τ′Δ[HHb], sum of effective τ′Δ[HHb], effective time constant (τΔ[HHb] + TD-Δ[HHb]). Parameter estimates for V̇o2p and HR were based on fitting to the end of exercise, whereas estimates for Δ[HHb] were based on fitting to a time corresponding to 5 × tV̇o2p.

Significantly different from YA (P < 0.05);

significantly different from 50 W (P < 0.05);

significantly different from phase II tV̇o2p (P < 0.05).

HR kinetics.

The rate of adjustment of HR (τHR) was greater (P < 0.05) in OA compared with YA during transitions to both 50 W and 80% θL. There were no differences in τHR between WR conditions in OA; however, YA displayed a greater τHR (P < 0.05) during the transition to 80% θL compared with 50 W (Table 3).

Δ[HHb] kinetics.

Baseline Δ[HHb] was similar between age groups for CL transitions to 50 W (YA: −5.11 ± 5.29 AU and OA: −6.46 ± 3.99 AU) and 80% θL (YA: −4.83 ± 3.77 AU and OA: −6.75 ± 3.63 AU). The Δ[HHb] amplitude was greater (P < 0.05) in YA than in OA; the Δ[HHb] amplitude for YA at 80% θL (9.13 ± 5.41 AU) was greater than for YA (P < 0.05) at 50 W (3.23 ± 1.79 AU), and both values were greater than for OA (P < 0.05) at 50 W (1.26 ± 0.66 AU) and 80% θL (1.99 ± 0.84 AU), which were not different between exercise conditions (Fig. 6). When expressed relative to the Δ[HHb] amplitude for RI exercise, the normalized Δ[HHb] amplitude for CL corresponded to 12% (50 W) and 35% (80% θL) for YA and to 7% (50 W) and 11% (80% θL) for OA.

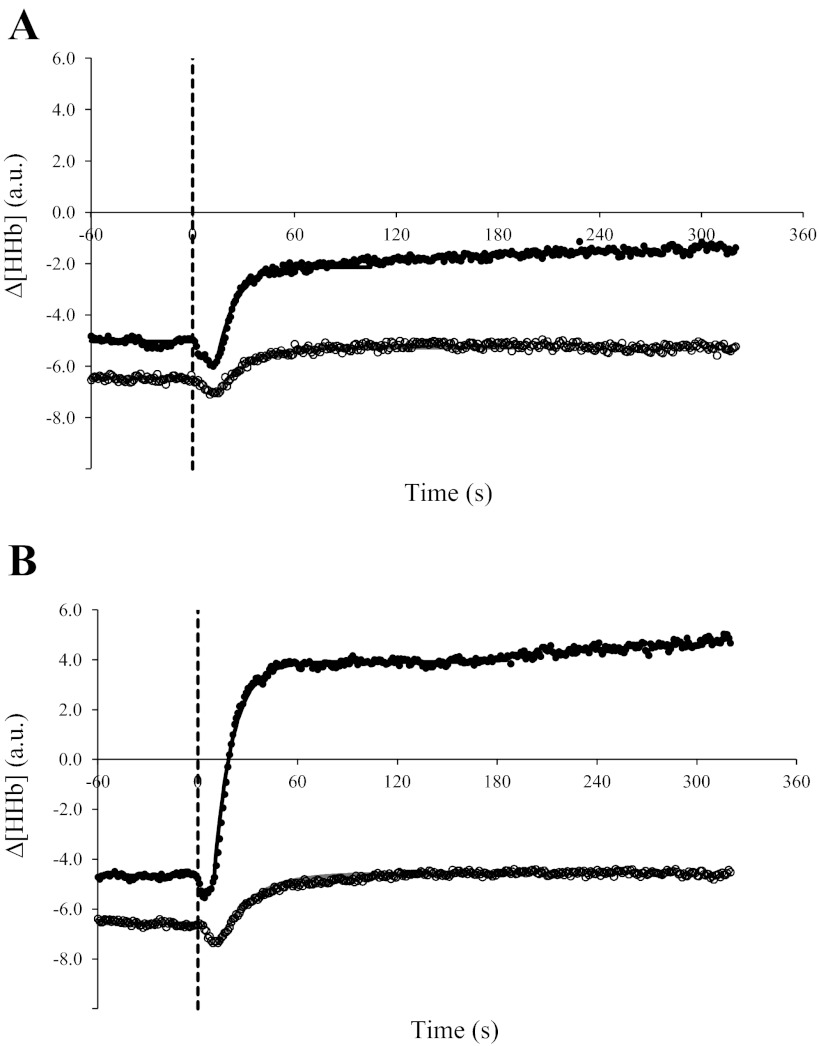

Fig. 6.

Group mean absolute Δ[HHb] response profiles to 50 W (A) and 80% θL (B) CL exercise in YA (●; n = 10) and OA (○; n = 9). The dashed line indicates the onset of CL exercise.

The rates of adjustment of Δ[HHb] (τΔ[HHb] and τ′Δ[HHb]) were not different with regard to age and exercise intensity (Fig. 6 and Table 3); in YA, TD-Δ[HHb] was shorter (P < 0.05) at 80% θL (10 ± 3 s) than at 50 W (15 ± 3 s), but in OA, there was no difference in TD-Δ[HHb] between exercise intensities (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first to examine the adjustments in Δ[HHb] and V̇o2p during nonsteady-state RI and steady-state CL exercise in YA and OA. The main findings of the present study were that 1) during RI exercise, after the initial kinetic phase, V̇o2p (reflecting muscle O2 utilization) increased linearly with increasing WR, whereas Δ[HHb] increased with a sigmoidal profile in both YA and OA; 2) during RI exercise, the normalized (relative to peak Δ[HHb]) Δ[HHb]-WR profile increased with a greater slope and was shifted leftward (toward lower WRs) in OA compared with YA; 3) the overall rate of adjustment for Δ[HHb] (measured as τ′Δ[HHb]) was not different between age groups for CL exercise intensities and was faster than the rate of adjustment of V̇o2p for YA and OA at 80% θL, whereas Δ[HHb] and V̇o2p kinetics were similar in each group during transitions to 50 W; and 4) the fundamental gain (ΔV̇o2p/ΔWR, the slope of the V̇o2p-WR relationship within the moderate-intensity domain), a reflection of the O2 cost of exercise, was lower in OA than in YA during nonsteady-state RI exercise but was not different between OA and YA for both intensities of steady-state CL exercise.

Nonsteady-State RI Exercise

In the present study, whereas V̇o2p increased linearly relative to WR, Δ[HHb] increased in a nonlinear, approximately sigmoidal manner with WR in both YA and OA. A sigmoidal increase in Δ[HHb] during RI exercise has previously been reported in YA (6, 20), but, to our knowledge, there have been no previous studies describing this pattern of response in OA; although an apparently higher deoxygenation was reported in OA compared with YA during step-incremental exercise by Ferri et al. (22), a detailed analysis of the response pattern was not reported. Assuming that V̇o2m increases linearly with increasing WR [as shown by the linear increase in V̇o2p, albeit with a lower slope in OA (see below)], the sigmoidal increase in muscle Δ[HHb] [reflecting the ratio of muscle blood flow (Qcap) to V̇o2m] implies nonlinear dynamics between microvascular O2 delivery (i.e., Qcap) and V̇o2m during nonsteady-state RI exercise in both YA and OA, as suggested by Ferreira et al. (20) for YA. While we acknowledge that this pattern of muscle microvascular blood flow changes during nonsteady-state RI exercise is speculative based, indirectly, on the relationship between Δ[HHb] and V̇o2p data, we are not aware of any current technology that allows continuous, nonsteady-state measures of muscle microvascular blood flow dynamics in exercising humans.

When the Δ[HHb] signal was normalized to the peak Δ[HHb] amplitude during RI exercise, the Δ[HHb] response increased at a faster rate in OA than in YA when expressed relative to absolute WR and was shifted leftward toward a lower absolute WR (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). Similar data have previously been reported by Ferri et al. (22), where a greater Δ[HHb] (vs. WR) was shown in OA compared with YA during step-incremental leg cycling and knee extension exercise to exhaustion. In the present study, at low WRs at the start of RI exercise, when the absolute demand for ATP and O2 were low, the increase in Δ[HHb] was not different in OA and YA. At higher WRs and ATP demands, the rate of increase in Δ[HHb] was greater in OA than in YA, reflecting greater fractional O2 extraction (Fig. 2B) and thus a lower ratio of Qcap to V̇o2m in OA as V̇o2m increased.

Therefore, as demonstrated by Ferreira et al. (20), the sigmoidal increase in the Δ[HHb]-WR relationship implies that the adjustment of Qcap was faster than that of V̇o2m (which is assumed to increase linearly with increasing WR) at the lower (light-intensity) WRs during RI exercise. The adjustment of Qcap slowed progressively during heavier intensity WRs until a plateau in the Δ[HHb]-WR relationship occurred, reflecting a relative “matching” in the rise of both Qcap and V̇o2m. A greater Δ[HHb] in OA compared with YA at any given absolute WR would be associated with a lower microvascular Po2 and, according to Fick's law of diffusion, would lower O2 diffusion into the muscle cell, as suggested by previous findings of Behnke et al. (5) in young and old rats. A slower rate of O2 diffusion to the muscle mitochondria in OA, presumably, might require a greater delivery of other oxidative substrates (including reducing equivalents, H+, ADP, and Pi) and lead to a greater disruption of metabolic “stability” (64), possibly contributing to premature fatigue.

The sigmoid-shaped increase in Δ[HHb] in both OA and YA (Figs. 3 and 4) is dependent on factors influencing the Qcap-to-V̇o2m relationship. It has been suggested that at the onset of exercise, an immediate increases in Qcap (relative to VO2m) occurs because of effects related to the muscle pump and rapid vasodilatation (8, 42, 56, 60). While these mechanisms may play a role at the onset of a step transition to CL exercise, their effects may be attenuated during RI exercise because the increase in WR above a baseline of 20-W cycling is not “instantaneous” but increases gradually in a “ramp-like” manner (20 W/min in the present study).

With increasing WR during RI exercise, there may be a progressive recruitment of muscle fibers having lower efficiency, as inferred from a greater steady-state O2 and phosphocreatine (PCr) cost per given change in WR (i.e., V̇o2p and PCr functional gain, respectively) and slower O2 utilization kinetics (7, 31, 32, 38, 62), even within a given muscle fiber population. In addition, the steady-state increase in the conduit artery blood flow-to-V̇o2p ratio is lower and the steady-state Δ[HHb]-to-V̇o2p ratio is higher during transitions to higher WRs, reflecting increased reliance on O2 extraction as WR increases, at least within the moderate-intensity domain (38). However, because the O2 extraction-O2 utilization relationship increases hyperbolically with increasing WR (21), a gradual “plateauing” in O2 extraction is expected at higher WRs (and V̇o2p), which is supported by the flattening of the Δ[HHb]-WR relationship in the present study (Fig. 3, A and B).

Additionally, with increasing WR, there is a progressive recruitment of type II muscle fibers according to the Henneman size principle. Ferreira et al. (21) examined the steady-state Qcap-to-V̇o2m relationship in rat muscles having a range of muscle fiber types and oxidative capacities and reported that, although the slope of the relationship was similar among different muscles, the intercept on the Qcap axis was lower in muscles having a predominantly fast-twitch fiber composition. As a consequence, the hyperbolic O2 extraction-to-V̇o2m relationship was shifted upward to a higher O2 extraction at lower levels of V̇o2m in these “fast-twitch” muscles (21). Therefore, as muscle type II fiber recruitment increases with increasing WR and V̇o2m during RI exercise, muscle O2 extraction might be expected to increase (for a given rate of V̇o2m) and then plateau, as would be expected given a hyperbolic O2 extraction-V̇o2m relationship.

The steady-state conduit artery blood flow-to-V̇o2p (or WR) relationship, generally, is attenuated in OA compared with YA (especially as intensity increases) (37, 45, 46, 48, 50, 61), although an unchanged relationship has been previously reported (49), especially in older men (45). Also, during the transition to a higher metabolic demand, the adjustment of conduit artery blood flow, HR, and vascular conductance are slower in OA compared with YA (18). Taken together, the lower blood flow and slower conduit artery blood flow kinetics in OA for a given rate of V̇o2m (or WR) suggests that a higher rate of O2 extraction (with greater Δ[HHb] and widening of the arterial-venous O2 content difference) would be required to support the O2 requirement of the muscle, as previously reported by others during steady-state exercise (15, 18, 27, 37, 46, 50, 61) and during transitions to WRs above moderate intensity (16, 27).

The differences in muscle O2 extraction (Δ[HHb]) between YA and OA could be attributed to the disparity in relative WR intensities (i.e., a given absolute WR will represent a higher relative intensity and greater percentage of maximal exercise for OA compared with YA). In the present study, the peak WR during RI exercise for OA (215 ± 31 W; Table 2) represents only 64% of the peak WR attained by YA during RI exercise (338 ± 30 W; Table 2). When normalized Δ[HHb] was expressed as a function of relative WR during RI exercise (Table 2 and Fig. 4), there were no differences in the parameter estimates for Δ[HHb] between YA and OA (Table 2), which could be related to the loss of lean muscle tissue that can occur with ageing. For example, it has been reported that for a similar thigh cross-sectional area, total muscle area and quadriceps muscle area are reduced, whereas the area of fat (and nonmuscle) tissue is increased, in OA, reflective of a reduced muscle mass in OA. Also, there is an increased infiltration of fat tissue within the muscle, reflective of reduced lean muscle in OA (43, 44, 51, 52). However, it was shown in single muscle fibers that when peak force and peak power were normalized for fiber size, there were no differences between YA and OA (59). Therefore, for any given absolute WR, in OA, where total lean muscle mass may be reduced compared with YA, this may require a greater percentage of the total lean muscle mass, but, presumably, in the submaximal range of absolute WRs studied here, adequate muscle recruitment is possible. Also, based on the results of the present study, during the RI protocol, the V̇o2p at any given WR was similar for YA and OA. During the CL protocol, the steady-state V̇o2p for exercise at the absolute WRs of 20 and 50 W were not different between YA and OA (0.92 and 1.19 l/min, respectively, for YA and 0.89 and 1.18 l/min, respectively, for OA). Thus, insofar as V̇o2p reflects the rate of O2 utilization in the exercising muscle, the total muscle mass likely is not an issue, as both OA and YA would recruit a similar muscle mass to generate the power required to complete a given absolute WR. Rather, at the same “relative” exercise intensity during nonsteady-state RI exercise, the relationship between sympathetic activation and parasympathetic withdrawal, or the production and release of vasodilatory metabolites from the exercising muscle, results in a similar reliance on muscle O2 extraction in YA and OA.

Steady-State CL Exercise

In the present study, although there was a tendency for τV̇o2p to be greater in OA (age main effect, P = 0.093), differences in τV̇o2p were not significant (50 W: 38 s in and 22 s in YA and 80% θL: 39 s in OA and 33 s and YA; Fig. 5 and Table 3). Slowed V̇o2p kinetics in OA are typically reported for step transitions in WR within the moderate-intensity domain (2, 15, 18, 27, 40, 55, 57). However, in the present study, estimated τV̇o2p in 5 of 10 YA was >30 s, and although τV̇o2p for healthy YA is generally reported to be ∼20–30 s (15, 55), recent studies (28, 29, 40) have reported τV̇o2p estimates of greater than ∼30 s for some YA.

In the present study, we also determined a substantial reserve for muscle O2 extraction, that is, during moderate-intensity CL exercise for both OA and YA, the steady-state Δ[HHb] amplitude represented only 10–35% of the Δ[HHb] amplitude measured during RI exercise. During the transition to 50-W exercise, Δ[HHb] kinetics (Fig. 6A and Table 3) were not different between YA and OA despite an apparently slower adjustment of V̇o2m in OA (Fig. 5A and Table 3), reflecting a poorer matching in the adjustment of Qcap (relative to V̇o2m) in OA, at least for “instantaneous” step transitions to a higher WR compared with more “gradual” increases in WR associated with RI exercise. However, for both age groups, step transitions to 80% θL were associated with a greater τV̇o2p (Fig. 5B and Table 3) relative to the overall adjustment of Δ[HHb] (τ′Δ[HHb]; Fig. 6B and Table 3), suggesting that at higher WRs, adjustments in Qcap may impose a limitation to the adjustment of V̇o2m. The mechanisms responsible for this limitation cannot be determined from the measurements of the present study. However, in YA, faster HR kinetics compared with V̇o2p kinetics were observed for the two CL WRs, whereas HR kinetics were similar or slower than V̇o2p kinetics during both CL exercise protocols for OA. These data suggest that in OA but not in YA, adjustments of cardiac output (and conduit artery blood flow) may limit V̇o2m kinetics (and V̇o2m), whereas the peripheral distribution of blood flow and O2 delivery within the active muscle microvasculature along with the delivery of oxidative substrate may constrain the adjustment of V̇o2p in both OA and YA (see Refs. 26–29, 40, and 41).

Age, Functional Gain, and Exercise Efficiency

A novel observation in this study was that the relationship between functional gain (ΔV̇o2p/ΔWR) and age was different for nonsteady-state RI and steady-state CL exercise. The functional gain reflects the O2 cost of exercise and is the inverse of exercise efficiency. In the present study, the functional gain calculated during CL exercise was not different between OA (9.9 ml·min−1·W−1) and YA (9.5 ml·min−1·W−1), in agreement with our previously published findings (14–16, 18, 27, 40), and suggests that exercise efficiency is not different between OA and YA. However, for the same group of adults performing RI exercise, the functional gain (calculated as the slope of the V̇o2p-WR relationship restricted to the moderate-intensity region of RI exercise) was lower in OA (8.7 ml·min−1·W−1) than in YA (10.0 ml·min−1·W−1), reflecting an apparently greater exercise efficiency in OA. We believe this to be the first study to report functional gain in OA during RI exercise. The lower gain in OA than in YA is surprising considering that we consistently found no differences between age groups (14–16, 18, 27, 40), at least when calculated during the steady state of CL exercise. There does not appear to be a consistent trend regarding the relationship between age and exercise efficiency. For example, Tevald and colleagues (58) reported a lower energy cost for twitch and tetanic muscle contractions in OA. Hepple and coworkers (30) found that compared with young rats (8–9 mo), O2 and ATP costs of contractions were greater in old rats (28–29 mo) but became lower in senescent rats (36 mo), suggesting that changes in efficiency with age might be variable. Conley and colleagues reported lower muscle oxidative capacity, lower mitochondrial volume density, and lower oxidative capacity per mitochondria (11) and reduced mitochondrial coupling efficiency (ATP/O) (9, 39) in older compared with younger animals and humans and that these changes may not be consistent across all muscles studied (9). In a recent review, Conley and coworkers (10) suggested that because of a lower mitochondrial coupling efficiency, the slope of the V̇o2p-WR relationship would be greater in OA compared with YA (see Fig. 3 in Ref. 10), not lower as in the present study. The lower slope for the V̇o2p-WR relationship observed in OA in the present study may be related to slower V̇o2p kinetics in OA such that the rise in V̇o2p was not able keep pace to the WR increment [and progressively rising O2 cost per WR increment; see above and Rossiter (53a) for discussion] used during RI exercise in both OA and YA in the present study (i.e., 20 W/min). Therefore, based on the similar functional gain in OA and YA reported in this and our other studies during steady-state CL exercise, we suggest that exercise efficiency is not adversely affected in the apparently healthy OA observed in the present study (age: ∼70 yr). It may be that the impairments in mitochondrial coupling efficiency reported by Conley and coworkers are not manifest at the whole body level until a much older age.

Limitations

A limitation with the NIRS technology used in the present study is that direct comparisons of “absolute” concentration and changes in Δ[HHb] between YA and OA groups and among adults within each of the age groups is not possible because of uncertainties regarding 1) initial values for path length, absorption, and scattering coefficients (i.e., as required when applying the Beer-Lambert law) and 2) whether these values change with exercise and intensity (19). Attenuation of NIR light as it passes through tissue is dependent not only on absorption by the chromophores of interest but also by attenuation due to photon scattering. Because there is a prevalence of scattering within biological tissues, the exact path length traveled by the photons through the tissue (i.e., between the NIRS emitter and detector optodes) is unknown. Whether these coefficients and responses are affected by aging has not been established.

Also, light must first pass through a relatively NIRS-inert adipose tissue layer before penetrating the active muscle layer. The depth of penetration is determined by the separation of NIRS emitter and detector optodes on the skin surface, and thus the actual volume of muscle being interrogated by NIRS is dependent inversely on the adipose tissue (and nonmuscle tissue) thickness. In general, it has been reported that aging is associated with an increase in adiposity (34), a redistribution in the pattern of adiposity (34), an increase in inter- and intramuscular fat (and nonmuscle tissue) deposits (34, 43, 44, 51, 52), and an increase in subcutaneous fat deposits (43, 44, 51, 52), although this may be influenced by the measurement site (34, 52). In the present study, although adipose tissue thickness was not measured, the attenuated Δ[HHb] response in OA may be related, in part, to a greater underlying subcutaneous, inter-, and intramuscular adipose tissue thickness, resulting in a smaller active muscle volume being interrogated.

Therefore, given these uncertainties, in the present study, the NIRS data were normalized for each subject in an effort to account for these effects. As described in methods, data were measured relative to a predetermined steady-state resting baseline and then normalized within the region bounded by values measured for baseline (20 W) cycling and the peak value measured during the RI protocol, thus providing a “functional” physiological normalization. The peak deoxygenation at the limit of tolerance will reflect conditions within a muscle contracting dynamically and having repeated periods (as dictated by the cadence associated with the cycling movement) of very high muscle force production near “maximal/peak” power outputs associated with very heavy-intensity exercise.

Conclusions

During RI exercise, Δ[HHb] increased as a near-sigmoid function relative to WR in both OA and YA. In OA, the slope of the Δ[HHb]-WR relationship was greater and the response was shifted to the left, reflecting greater deoxygenation for a given absolute WR and V̇o2p. Also, during CL exercise, V̇o2p kinetics tended to be slower in OA than in YA, whereas Δ[HHb] kinetics were not different between OA and YA. Therefore, the greater Δ[HHb] (reflecting muscle fractional O2 extraction) for a given change in V̇o2p (and V̇o2m) seen in OA than in YA during both RI and CL exercise supports the suggestion that microvascular blood adjustments are attenuated in OA relative to YA during transitions associated with RI and CL exercise. The slowed V̇o2p kinetics in OA likely also contribute to the lower functional gain calculated during nonsteady-state RI exercise as the functional gain calculated during steady-state CL exercise is not different between OA and YA, suggesting that there is no measureable reduction in exercise efficiency in healthy OA.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the University of Western Ontario Academic Development Fund, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, and the Ontario Innovation Trust. Additional support was provided by Standard Life Assurance Company of Canada. J. M. Murias was supported by a doctoral research scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: B.M.G., J.M.M., M.D.S., D.H.P., and J.M.K. conception and design of research; B.M.G., J.M.M., and M.D.S. performed experiments; B.M.G., J.M.M., and M.D.S. analyzed data; B.M.G., J.M.M., M.D.S., D.H.P., and J.M.K. interpreted results of experiments; B.M.G. prepared figures; B.M.G. drafted manuscript; B.M.G., J.M.M., M.D.S., D.H.P., and J.M.K. edited and revised manuscript; B.M.G., J.M.M., M.D.S., D.H.P., and J.M.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express gratitude to the participants of this study and acknowledge the assistance provided by Brad Hansen.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersen P, Saltin B. Maximal perfusion of skeletal muscle in man. J Physiol 366: 233–249, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babcock MA, Paterson DH, Cunningham DA, Dickinson JR. Exercise on-transient gas exchange kinetics are slowed as a function of age. Med Sci Sports Exerc 26: 440–446, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barstow TJ, Lamarra N, Whipp BJ. Modulation of muscle and pulmonary O2 uptakes by circulatory dynamics during exercise. J Appl Physiol 68: 979–989, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beaver WL, Lamarra N, Wasserman K. Breath-by-breath measurement of true alveolar gas exchange. J Appl Physiol 51: 1662–1675, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behnke BJ, Delp MD, Dougherty PJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effects of aging on microvascular oxygen pressures in rat skeletal muscle. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 146: 259–268, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boone J, Koppo K, Barstow TJ, Bouckaert J. Pattern of deoxy[Hb+Mb] during ramp cycle exercise: influence of aerobic fitness status. Eur J Appl Physiol 105: 851–859, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brittain CJ, Rossiter HB, Kowalchuk JM, Whipp BJ. Effect of prior metabolic rate on the kinetics of oxygen uptake during moderate-intensity exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 86: 125–134, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clifford PS, Tschakovsky ME. Rapid vascular responses to muscle contraction. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 36: 25–29, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conley KE, Amara CE, Jubrias SA, Marcinek DJ. Mitochondrial function, fibre types and ageing: new insights from human muscle in vivo. Exp Physiol 92: 333–339, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Amara CE, Marcinek DJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction: impact on exercise performance and cellular aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 35: 43–49, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. J Physiol 526: 203–210, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis JA, Whipp BJ, Lamarra N, Huntsman DJ, Frank MH, Wasserman K. Effect of ramp slope on determination of aerobic parameters from the ramp exercise test. Med Sci Sports Exerc 14: 339–343, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Day JR, Rossiter HB, Coats EM, Skasick A, Whipp BJ. The maximally attainable V̇o2 during exercise in humans: the peak vs. maximum issue. J Appl Physiol 95: 1901–1907, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Adaptation of pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics and muscle deoxygenation at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in young and older adults. J Appl Physiol 98: 1697–1704, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Effect of age on O2 uptake kinetics and the adaptation of muscle deoxygenation at the onset of moderate-intensity cycling exercise. J Appl Physiol 97: 165–172, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Effects of prior heavy-intensity exercise on pulmonary O2 uptake and muscle deoxygenation kinetics in young and older adult humans. J Appl Physiol 97: 998–1005, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Relationship between pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics and muscle deoxygenation during moderate-intensity exercise. J Appl Physiol 95: 113–120, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. duManoir GR, DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Differences in exercise limb blood flow and muscle deoxygenation with age: contributions to O2 uptake kinetics. Eur J Appl Physiol 110: 739–751, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferreira LF, Hueber DM, Barstow TJ. Effects of assuming constant optical scattering on measurements of muscle oxygenation by near-infrared spectroscopy during exercise. J Appl Physiol 102: 358–367, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferreira LF, Koga S, Barstow TJ. Dynamics of noninvasively estimated microvascular O2 extraction during ramp exercise. J Appl Physiol 103: 1999–2004, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferreira LF, McDonough P, Behnke BJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Blood flow and O2 extraction as a function of O2 uptake in muscles composed of different fiber types. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 153: 237–249, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferri A, Adamo S, Longaretti M, Marzorati M, Lanfranconi F, Marchi A, Grassi B. Insights into central and peripheral factors affecting the “oxidative performance” of skeletal muscle in aging. Eur J Appl Physiol 100: 571–579, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grassi B, Pogliaghi S, Rampichini S, Quaresima V, Ferrari M, Marconi C, Cerretelli P. Muscle oxygenation and pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during cycling exercise on-transitions in humans. J Appl Physiol 95: 149–158, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grassi B, Poole DC, Richardson RS, Knight DR, Erickson BK, Wagner PD. Muscle O2 uptake kinetics in humans: implications for metabolic control. J Appl Physiol 80: 988–998, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grassi B, Porcelli S, Salvadego D, Zoladz JA. Slow V̇o2 kinetics during moderate-intensity exercise as markers of lower metabolic stability and lower exercise tolerance. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 345–355, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gurd BJ, Peters SJ, Heigenhauser GJ, LeBlanc PJ, Doherty TJ, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Prior heavy exercise elevates pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and muscle oxygenation and speeds O2 uptake kinetics during moderate exercise in older adults. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R877–R884, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gurd BJ, Peters SJ, Heigenhauser GJ, LeBlanc PJ, Doherty TJ, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. O2 uptake kinetics, pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, and muscle deoxygenation in young and older adults during the transition to moderate-intensity exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R577–R584, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gurd BJ, Peters SJ, Heigenhauser GJ, LeBlanc PJ, Doherty TJ, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Prior heavy exercise elevates pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and speeds O2 uptake kinetics during subsequent moderate-intensity exercise in healthy young adults. J Physiol 577: 985–996, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gurd BJ, Scheuermann BW, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Prior heavy-intensity exercise speeds V̇o2 kinetics during moderate-intensity exercise in young adults. J Appl Physiol 98: 1371–1378, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hepple RT, Hagen JL, Krause DJ, Baker DJ. Skeletal muscle aging in F344BN F1-hybrid rats: II. Improved contractile economy in senescence helps compensate for reduced ATP-generating capacity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59: 1111–1119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hughson RL, Morrissey M. Delayed kinetics of respiratory gas exchange in the transition from prior exercise. J Appl Physiol 52: 921–929, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, Fulford J. Muscle [phosphocreatine] dynamics following the onset of exercise in humans: the influence of baseline work-rate. J Physiol 586: 889–898, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Krustrup P, Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, Calbet JA, Bangsbo J. Muscular and pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics during moderate- and high-intensity sub-maximal knee-extensor exercise in humans. J Physiol 587: 1843–1856, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuk JL, Saunders TJ, Davidson LE, Ross R. Age-related changes in total and regional fat distribution. Ageing Res Rev 8: 339–348, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamarra N, Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Wasserman K. Effect of interbreath fluctuations on characterizing exercise gas exchange kinetics. J Appl Physiol 62: 2003–2012, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lawrenson L, Hoff J, Richardson RS. Aging attenuates vascular and metabolic plasticity but does not limit improvement in muscle V̇o2 max. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1565–H1572, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawrenson L, Poole JG, Kim J, Brown C, Patel P, Richardson RS. Vascular and metabolic response to isolated small muscle mass exercise: effect of age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1023–H1031, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MacPhee SL, Shoemaker JK, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Kinetics of O2 uptake, leg blood flow, and muscle deoxygenation are slowed in the upper compared with lower region of the moderate-intensity exercise domain. J Appl Physiol 99: 1822–1834, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marcinek DJ, Schenkman KA, Ciesielski WA, Lee D, Conley KE. Reduced mitochondrial coupling in vivo alters cellular energetics in aged mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol 569: 467–473, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murias JM, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Speeding of VO2 kinetics with endurance training in old and young men is associated with improved matching of local O2 delivery to muscle O2 utilization. J Appl Physiol 108: 913–922, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murias JM, Spencer MD, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Muscle deoxygenation to V̇o2 relationship differs in young subjects with varying τV̇o2. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 3107–3118, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nadland IH, Walloe L, Toska K. Effect of the leg muscle pump on the rise in muscle perfusion during muscle work in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 105: 829–841, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Overend TJ, Cunningham DA, Kramer JF, Lefcoe MS, Paterson DH. Knee extensor and knee flexor strength: cross-sectional area ratios in young and elderly men. J Gerontol 47: M204–M210, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Overend TJ, Cunningham DA, Paterson DH, Lefcoe MS. Thigh composition in young and elderly men determined by computed tomography. Clin Physiol 12: 629–640, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parker BA, Smithmyer SL, Pelberg JA, Mishkin AD, Proctor DN. Sex-specific influence of aging on exercising leg blood flow. J Appl Physiol 104: 655–664, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Poole JG, Lawrenson L, Kim J, Brown C, Richardson RS. Vascular and metabolic response to cycle exercise in sedentary humans: effect of age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1251–H1259, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Porcelli S, Marzorati M, Lanfranconi F, Vago P, Pisot R, Grassi B. Role of skeletal muscles impairment and brain oxygenation in limiting oxidative metabolism during exercise after bed rest. J Appl Physiol 109: 101–111, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Proctor DN, Koch DW, Newcomer SC, Le KU, Leuenberger UA. Impaired leg vasodilation during dynamic exercise in healthy older women. J Appl Physiol 95: 1963–1970, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Proctor DN, Newcomer SC, Koch DW, Le KU, MacLean DA, Leuenberger UA. Leg blood flow during submaximal cycle ergometry is not reduced in healthy older normally active men. J Appl Physiol 94: 1859–1869, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Proctor DN, Shen PH, Dietz NM, Eickhoff TJ, Lawler LA, Ebersold EJ, Loeffler DL, Joyner MJ. Reduced leg blood flow during dynamic exercise in older endurance-trained men. J Appl Physiol 85: 68–75, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rice CL, Cunningham DA, Paterson DH, Lefcoe MS. A comparison of anthropometry with computed tomography in limbs of young and aged men. J Gerontol 45: M175–M179, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rice CL, Cunningham DA, Paterson DH, Lefcoe MS. Arm and leg composition determined by computed tomography in young and elderly men. Clin Physiol 9: 207–220, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Richardson RS, Kennedy B, Knight DR, Wagner PD. High muscle blood flows are not attenuated by recruitment of additional muscle mass. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H1545–H1552, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53a. Rossiter HB. Exercise: kinetic considerations for gas exchange. Comp Physiol 1: 203–244, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rossiter HB, Ward SA, Doyle VL, Howe FA, Griffiths JR, Whipp BJ. Inferences from pulmonary O2 uptake with respect to intramuscular [phosphocreatine] kinetics during moderate exercise in humans. J Physiol 518: 921–932, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scheuermann BW, Bell C, Paterson DH, Barstow TJ, Kowalchuk JM. Oxygen uptake kinetics for moderate exercise are speeded in older humans by prior heavy exercise. J Appl Physiol 92: 609–616, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sheriff DD, Hakeman AL. Role of speed vs. grade in relation to muscle pump function at locomotion onset. J Appl Physiol 91: 269–276, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Spencer MD, Murias JM, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Pulmonary O2 uptake and muscle deoxygenation kinetics are slowed in the upper compared with lower region of the moderate-intensity exercise domain in older men. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 2139–2148, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tevald MA, Foulis SA, Lanza IR, Kent-Braun JA. Lower energy cost of skeletal muscle contractions in older humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R729–R739, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Trappe S, Gallagher P, Harber M, Carrithers J, Fluckey J, Trappe T. Single muscle fibre contractile properties in young and old men and women. J Physiol 552: 47–58, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tschakovsky ME, Sheriff DD. Immediate exercise hyperemia: contributions of the muscle pump vs. rapid vasodilation. J Appl Physiol 97: 739–747, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wahren J, Saltin B, Jorfeldt L, Pernow B. Influence of age on the local circulatory adaptation to leg exercise. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 33: 79–86, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wilkerson DP, Jones AM. Effects of baseline metabolic rate on pulmonary O2 uptake on-kinetics during heavy-intensity exercise in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 156: 203–211, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wilkerson DP, Jones AM. Influence of initial metabolic rate on pulmonary O2 uptake on-kinetics during severe intensity exercise. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 152: 204–219, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zoladz JA, Korzeniewski B, Grassi B. Training-induced acceleration of oxygen uptake kinetics in skeletal muscle: the underlying mechanisms. J Physiol Pharmacol 57: 67–84, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]