Motivational interviewing is a tool for changing patients’ medication-taking behavior.

Abstract

For patients, poor adherence to biologics can increase risks of morbidity and mortality. For payers, it means money down the drain. Here’s a tool that proponents say can help change patient behavior.

Despite the benefits of patient-administered biologics and the severity of the diseases for which they are prescribed, there is evidence that patients do not start and persist with treatment. Grant Corbett, principal at Behavior Change Solutions, advises managed care and pharmaceutical organizations on how to improve patient adherence. This requires addressing primary nonadherence (i.e., the percentage of patients who don’t fill initial prescriptions) and 12-month persistence rates,1 Corbett says.

In the United States, about 23 percent of prescriptions for biologics are never filled, says Corbett. Consider biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). One study has shown that only 44 percent to 62 percent of patients who start a biologic DMARD remain on the medication at 1 year, a rate comparable to that for non biologic DMARDs (Blum 2011).

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a gentle form of counseling developed in the 1980s to address alcohol abuse. Since then, it has been applied to a range of health behaviors, including medication adherence. MI doesn’t work for everyone — clinical trials of MI have shown positive results in patients taking a medication for multiple sclerosis (Berger 2005) and negative results in patients taking osteoporosis drugs (Solomon 2012). But employed by clinicians who take the time to become skilled at it, MI could help patients decide for themselves that they want to take their biologic after all.

“Patients are rarely asked, ‘What do you hope this drug will do for you?’” says Grant Corbett, principal at Behavior Change Solutions. “Asking such a question enhances the likelihood of adherence.”

“If MI has shown mixed results in clinical trials of medication adherence, it may be because beliefs in healthcare result in adaptations of MI that are not consistent with the research,” says Corbett. For example, healthcare has embraced the view that patient nonadherence is the result of knowledge deficits, which rationalizes “patient education.” If this “deficit worldview” assumption were accurate, Corbett says, improving patients’ knowledge of their conditions and treatments should lead to improved adherence. Yet more than 100 published studies show no such association.

So what is needed to motivate medication adherence? Corbett proposes that the research supports the need to view patients as competent. From a “competence worldview,” MI can be regarded as a technique for facilitating a patient’s knowledge, beliefs, and capabilities in the direction of change. “Whether MI or any patient messaging is implemented from the deficit or competence worldview can mean the difference between limited or no impact on adherence — or significant improvement in outcomes,” says Corbett.

William R. Miller, PhD, emeritus distinguished professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of New Mexico, is the father of MI, having introduced the concept in 1983. Since then, he has written widely about MI with his frequent collaborator Stephen Rollnick, PhD. Miller and Rollnick emphasize that MI consists of four processes: engaging the patient; focusing on an issue; evoking the patient’s thoughts on the matter; and planning what to do about it (Miller 2012). For example, if the issue is adherence to an oral oncolytic and the patient is committed to action, then the clinician skips from the engagement step to the planning step and tries to learn how the patient intends to fit multiple doses of the drug into his or her schedule.

Above all, Miller emphasizes, MI is collaborative, grounded in the knowledge that no one other than the patient can take a medication as instructed or change some other health behavior. MI also is evocative in that it brings forth the goals and values that a patient already has and uses them as the basis for changing a specific behavior. And MI respects the patient’s autonomy — it helps patients make their own choices about their health behavior. Acknowledgement of a patient’s freedom to decide may, in the end, lead to a change in behavior that is in the patient’s best interest.

Four principles, three skills

MI is guided by four principles captured by the mnemonic RULE (Table 1). These principles are implemented using the conversational styles that people use every day: following, directing, and guiding — people use all three styles but tend to favor one of them. Those who favor the following style tend to listen a lot but provide little information. Psychologists and psychiatrists, for example, use this style. People who use the directing style tend to spend most of their time informing but not very much time listening. For example, a physician may be happy to tell a patient what to do to improve adherence to a biologic but may have little interest in hearing what the patient thinks about it. The directing style is what physicians are exposed to during medical education and training.

TABLE 1.

Guiding principles of motivational interviewing: RULE

| Resist righting reflex |

|

| Understand patient’s motivation |

|

| Listen to patient |

|

| Empower patient |

|

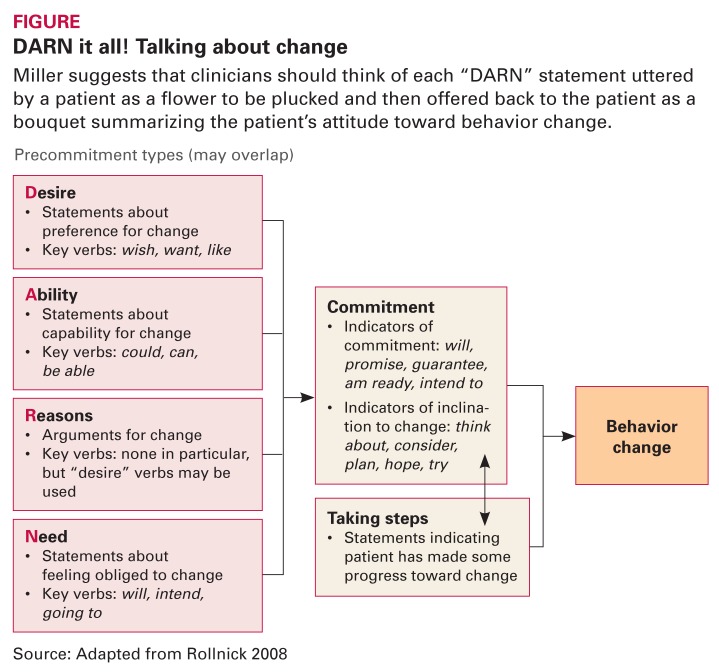

The guiding style strives to achieve a balance among asking, listening, and informing. MI is a gentle form of guiding that is directed toward a specific goal (e.g., improving adherence to a biologic). It draws on listening skills to find clues about a patient’s desire, ability, reasons, and need to change (Figure, page 12). In the course of informing the patient about the benefits and risks of taking a medication, the physician evokes the patient’s own arguments for adherence.

FIGURE.

DARN it all! Talking about change

Miller suggests that clinicians should think of each “DARN” statement uttered by a patient as a flower to be plucked and then offered back to the patient as a bouquet summarizing the patient’s attitude toward behavior change.

Source: Adapted from Rollnick 2008

Asking. Clinicians tend to ask closed questions that cut off conversation — “When was the last time you injected your biologic?” MI thrives on open questions that can lead to talk about change — “How do you fit your oral oncolytic into your daily routine?”

“So much of what we do in health-care erects barriers to adherence,” Corbett notes. “We don’t give patients the opportunity to talk things through.”

Clinicians may also find it helpful to use a ruler — actual or verbal — to learn about a patient’s motivations with respect to behavior change, says Corbett. For example, the closed question “On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 means ‘not important at all’ and 10 means ‘highly important,’ how important is it to you to take your oral oncolytic twice every day?” will yield a number along that scale. If the patient’s answer is 6, the follow-up question could be “What would need to be different for you to rate it an 8 or a 9?” The answer provides the clinician an entry point for discussing an action plan.

Listening. Miller says that listening is the key skill in MI because it is only by truly listening to the patient that the clinician can detect the specific behavior change desired. While listening, the clinician should be careful not to erect verbal roadblocks (Table 2, page 12). Even statements that appear to be positive can derail a patient’s train of thought. Also, the clinician should tamp down his or her thoughts in order to concentrate on the patient’s words. Corbett notes that all the behaviors in Table 2 are judgments — even if positive — and can evoke resistance. “MI provides nonjudgmental alternatives to each of these behaviors, such as affirming instead of agreeing and empathy instead of sympathy.”

TABLE 2.

Common roadblocks to effective listening

| • Agreeing | •Disagreeing |

| • Approving | •Disapproving |

| •Sympathizing | •Shaming |

| •Reasoning | •Arguing |

| •Persuading | •Dissuading |

| •Reassuring | •Warning |

| •Instructing | •Correcting |

| •Analyzing |

Source: Adapted from Rollnick 2008

Informing. When adherence is a concern, the clinician needs to give the patient information, such as the likely benefits of taking a medication and the possible risks in not doing so. Miller says there are two ways of informing the patient. In the first method, the clinician provides a digestible chunk of information to the patient, checks to see that the patient understands it, and then moves on the next chunk. This chunk-check-chunk method, which seeks out teachable moments, has the advantage of converting a lecture into a conversation.

The second method looks for “learning opportunities.” The clinician should first elicit information through an open question — “What would you most like to know about taking your biologic?” or “What do you already know about taking your biologic?” This lets the clinician correct misconceptions and draws the patient into a conversation about adherence. After the patient has responded, the clinician provides the appropriate information and then asks another open question to elicit the patient’s response.

Whether the chunk-check-chunk approach or the elicit-provide-elicit approach is used depends on the clinician. The elicit-provide-elicit approach may be more effective for fostering behavior change because it lets the clinician identify and respond to the numerous factors that make adherence so challenging, such as cultural values and personal habits. If clinicians take their usual approach and focus only on the knowledge deficit, then they may never uncover the real reasons underlying poor adherence.

Footnotes

Definitions vary, but compliance generally means taking a drug as prescribed. Persistence refers to continuation of a drug from the initial fill to discontinuation, which can be measured by claims. Adherence is an umbrella term that refers to acceptance of an initial prescription, filling the prescription, compliance, and persistence.

References

- Berger BA, Liang H, Hudmon KS. Evaluation of software-based telephone counseling to enhance medication persistency among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45:466–472. doi: 10.1331/1544345054475469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum MA, Koo D, Doshi JA. Measurement and rates of persistence with and adherence to biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Ther. 2011;33:901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon DH, Iversen MD, Avorn J, et al. Osteoporosis telephonic intervention to improve medication regimen adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:477–483. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]