Abstract

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) share pathophysiological mechanisms and often co-occur. Yet it is not known whether ED provides an early warning for increased CVD or other causes of mortality.

Aim

We sought to examine the association of ED with all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Methods

Prospective, population-based study of 1,709 men (of 3,258 eligible) aged 40–70 years. ED was measured by self-report. Subjects were followed for a mean of 15 years. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Main outcome measures

Mortality due to all causes, CVD, malignant neoplasms, and other causes.

Results

Of 1,709 men, 1,284 survived to the end of 2004 and had complete ED and age data. Of 403 men who died, 371 had complete data. After adjustment for age, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, cigarette smoking, self-assessed health, and self-reported heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, ED was associated with HRs of 1.26 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.57] for all-cause mortality and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.00–2.05) for CVD mortality. The HR for CVD mortality associated with ED is of comparable magnitude to HRs of some conventional CVD risk factors.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate that ED is significantly associated with increased all-cause mortality, primarily through its association with CVD mortality.

Keywords: Aging, erectile dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, longitudinal studies, men, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Erectile dysfunction (ED) affects approximately 18 million men aged 20 years or older in the US.1 With aging of the U.S. and worldwide population, a considerable increase in the prevalence of ED is projected.2 The factors that increase risk of ED include older age, depression, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors.3–7 The relationship between ED and CVD has received substantial attention. The prevailing notion supported by relatively scant data is that ED may serve as a sentinel marker for CVD.8–18 This is based largely on shared pathophysiological mechanisms (e.g., endothelial dysfunction, arterial occlusion, systemic inflammation)8, 11, 14, 19–24 and risk factors,4, 6, 11, 25–28 the high co-prevalence of both conditions,5, 13, 15, 29, 30 and the reasonable premise that progressive occlusive disease should manifest earlier in the microvasculature than in larger vessels.14, 31 Prospective studies examining ED as a sentinel for CVD are rare, but recent data from the placebo arm of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT),32 the Olmstead County Study,33 as well as others34, 35 provide some support, although not for the most meaningful end-points of cardiovascular and overall mortality. Any link between ED and mortality would have important clinical implications in light of the observation that sudden death may be the first manifestation of CVD.36–38

To our knowledge, PCPT is the only study to examine the association between ED and mortality risk.32 In that study, death from any cause was unrelated to prevalent or incident ED. The number of deaths in PCPT, however, was relatively small and follow-up was short at 7 years. Our objective was to examine the association of ED with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a well-characterized cohort of men who were followed over a mean of 15 years. We tested the hypothesis that ED predicts all-cause mortality, primarily through its association with CVD mortality.

METHODS

Sample

The Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) is a prospective observational cohort study of aging, health, and endocrine and sexual function in a population-based random sample of men between ages 40–70 y.39 A total of 1,709 respondents (52% of 3,258 eligible) completed the baseline (1987–89; baseline) protocol. MMAS subjects were observed again in 1995–97 (n=1,156, 77% response rate) and 2002–04 (n=853, 65% response rate). These response rates were expected given the requirements for early-morning phlebotomy and extensive in-person interviews. Participants received no financial incentive at baseline, and $50 and $75 remunerations at the first and second follow-ups, respectively.

Protocol

Extensive details on the MMAS have been published elsewhere.39 The core field protocol for MMAS remained the same between throughout the study. A trained field technician/phlebotomist visited each subject at home, administered a health questionnaire, and obtained two non-fasting blood samples. Anthropometrics (height, weight, hip and waist circumference) and blood pressure were directly measured according to standard protocols developed for large-scale fieldwork.40 Two non-fasting blood samples were drawn and serum was pooled for analysis. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was measured at a CDC-certified lipid laboratory (Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI). The following information was collected via interviewer-administered questionnaire: demographics, psychosocial factors, history of chronic disease, self-assessed general health status, tobacco and alcohol use, nutritional intake, and physical activity/energy expenditure during the past seven days. MMAS received institutional review board approval and all participants gave written informed consent.

Covariates

A common set of variables was used to control for confounding in multivariate statistical models. Age and body mass index (BMI) were input as continuous variables. In addition, the following categorical variables were included: alcohol consumption (< 1, 1, and 2+ drinks/day), calories expended in physical activity (none, < 200 kcal/day, and ≥ 200 kcal/day), current cigarette smoking, self-assessed health (excellent, very good, good, fair/poor), and self-reported chronic disease (heart disease, hypertension and diabetes).

Erectile dysfunction

At the end of the interview, the subject was given a 23-item questionnaire on sexual activity to be completed in private and returned in a sealed envelope.41 The questionnaire included 13 items related to ED; e.g., “During the last six months have you ever had trouble getting an erection before intercourse begins?” The 13 items were combined in a discriminant-analytic formula to assign a degree of erectile function to each subject.42 The same discriminant formula was used at both baseline and follow-up.

Calibration data for the discriminant formula were taken from an additional single-question, subjective self-assessment of ED, included in the follow-up questionnaire in response to recommendations of the NIH Consensus Panel.3 Impotence was defined as “being able to get and keep an erection that is rigid enough for satisfactory sexual activity.” The subject rated himself as completely impotent (“never able to get and keep an erection …”), moderately impotent (“sometimes able …”), minimally impotent (“usually able…”), or not impotent (“always able …”). In random subsets of the follow-up samples the self-assessment was validated43 against two established ED measures, the International Index of Erectile Function44 (r = 0.71, n = 254) and the Brief Male Sexual Function Inventory45 (r = 0.78, n = 251), as well as an independent urologic assessment.46 As we have done in previous analyses,4, 5, 47 we analyzed both the 4-category ED status variable and also a binary ED status variable (absence/presence) which was defined as moderate or complete ED.

Vital status and cause of death

Vital status of MMAS respondents was ascertained through the year 2004 by linking the MMAS database with the National Death Index (NDI).48 Cause of death was ascertained via the NDI Plus service, which provides causes of death according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Before 1999, deaths were coded according to the ICD, 9th Revision and subsequently, according to the ICD, 10th Revision. As we have done previously,49 we categorized deceased respondents according to underlying cause of death. We considered deaths from all-causes and those due to: diseases of the circulatory system (ICD-9/ICD-10 codes 390–459/I00-I99), which we refer to as CVD death and includes coronary heart disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other vascular diseases;50 malignant neoplasms (ICD-9/ICD-10 codes 140–208 and 235–238/C00-C97 and D37–D48); and other causes. NDI Plus matches nosologist coding of cause of death within organ system in 97% of cases.51

Statistical analysis

Person-years (py) were accumulated from each subject's baseline visit to date of death or December 31, 2004. We computed mortality rates (deaths/py) in each ED category, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated under the assumption that mortality rates followed a Poisson distribution.52 Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model;53 men with no ED served as the reference group for the 4-category ED variable and men with no or minimal ED served as the reference group for the binary ED variable in the calculation of HRs. To allow for changes in ED status during the follow-up period,54 ED was modeled as a time-dependent covariate. Tests for linear trend across the 4-category ED variable were performed by creating linear contrasts. Significance was tested with Wald Chi-Square tests and was considered present when p < .05.

RESULTS

As of December 31, 2004, there were 403 deaths and 1,306 surviving members of the MMAS. Of the deceased men, 371 had complete data on ED and age. Of those who were known to be alive, 1,284 had complete data on ED and age. In total, we included 1,655 men who contributed 25,114 person-years of follow-up (mean follow-up: 15.2 years) to the analysis. The largest number of deaths (n=140, 37.7%) were due to CVD. There were 124 cancer deaths (33.4%) and 107 deaths from other causes (28.8%).

At baseline, the percentage of men in the four ED categories in this analysis sample was as follows: none (56%), minimal (23%), moderate (8%), and complete (12%). Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of men according to ED status, categorized as absent (none or minimal ED, n = 1,317) and present (moderate or complete ED, n = 388). Men with ED were older (60 ± 8 y) than men without ED (54 ± 8 y). Men with ED were less likely to report that they were currently employed, had lower household income, were more likely to have been diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes, had worse overall health, a higher prevalence of smoking, and more light drinking. Men with ED also had slightly higher BMI and waist circumference, higher caloric intake and lower calorie expenditure, lower HDL cholesterol, higher SBP, and higher mean depression scores.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of analytic sample by baseline ED status.

| ED absent (n=1,317) | ED present (n=338) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| N or mean | (% or SD) | N or mean | (% or SD) | |

| Age group (10-y) | ||||

| 40–49 yrs | 511 | (39) | 47 | (14) |

| 50–59 yrs | 464 | (35) | 91 | (27) |

| 60–70 yrs | 342 | (26) | 200 | (59) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1254 | (95) | 331 | (98) |

| Black | 41 | (3) | 4 | (1) |

| Other | 20 | (2) | 3 | (1) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 126 | (10) | 32 | (9) |

| Currently married | 1020 | (77) | 253 | (75) |

| Divorced/Separated | 142 | (11) | 35 | (10) |

| Widowed | 29 | (2) | 18 | (5) |

| Currently employed | 1109 | (84) | 206 | (61) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 323 | (25) | 132 | (39) |

| Some college or BA | 552 | (42) | 140 | (41) |

| Advanced study beyond BA | 442 | (34) | 66 | (20) |

| Annual household income | ||||

| < $40,000 | 434 | (34) | 170 | (53) |

| $40,000–$79,999 | 564 | (44) | 115 | (36) |

| ≥ $80,000 | 288 | (22) | 36 | (11) |

| Heart disease | 129 | (10) | 73 | (22) |

| Hypertension | 371 | (28) | 121 | (36) |

| Diabetes | 75 | (6) | 50 | (15) |

| Self-assessed health | ||||

| Excellent | 461 | (35) | 58 | (17) |

| Very good | 482 | (37) | 108 | (32) |

| Good | 290 | (22) | 124 | (37) |

| Fair/poor | 82 | (6) | 48 | (14) |

| Current smoking | 299 | (23) | 95 | (28) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| < 1 drink/day | 681 | (52) | 197 | (59) |

| 1 drink/day | 383 | (29) | 72 | (22) |

| 2+ drinks/day | 243 | (19) | 65 | (19) |

| Calories expended in physical activity | ||||

| None | 76 | (6) | 43 | (13) |

| < 200 kcal/day | 348 | (26) | 112 | (33) |

| ≥ 200 kcal/day | 893 | (68) | 182 | (54) |

| Caloric intake (kcal/day) | 2,087 | (766) | 2,058 | (869) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.2 | (4.3) | 27.8 | (4.7) |

| Waist circumference (in) | 38.2 | (4.4) | 39.1 | (4.9) |

| High-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) | 43.3 | (13.7) | 39.9 | (12.9) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 126.0 | (15.6) | 130.0 | (18.0) |

| Depression score | 6.1 | (6.9) | 7.8 | (8.2) |

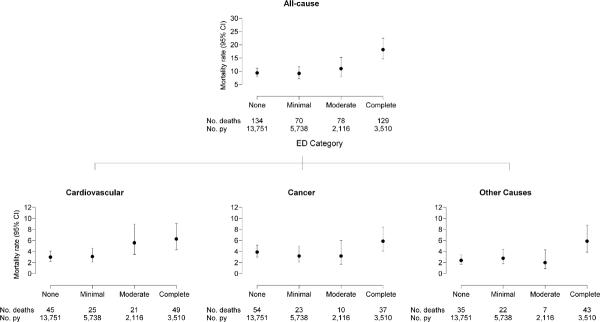

Age-adjusted mortality rates with 95% CIs are displayed in Figure 1 and associated HRs adjusted for age are displayed in Table 2. Data not shown provide no evidence to suggest variation in the associations between ED and mortality by age (all ED × age group interaction p-values ≥ .19). Cancer mortality exhibited no association with ED (HR = 1.30, 95% CI, 0.89–1.90). Risk of mortality due to CVD increased as ED severity increased (p < .001). The age-adjusted HR for CVD death in men with moderate/complete ED compared to men with no/minimal ED was 1.87 (95% CI, 1.32–2.64). Risk of death due to other causes was significantly associated with ED (HR = 1.64, 95% CI, 1.11–2.45), but not in a dose-dependent fashion. The risk of all-cause mortality was considerably higher in men with complete ED. The age-adjusted HR for moderate/complete ED compared with none/minimal ED was 1.60 (95% CI, 1.29–1.98).

FIGURE 1.

Age-adjusted all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) according to level of erectile dysfunction. Rates are adjusted to the mean age of the analytic sample (55 y). Person-years = py.

TABLE 2.

Age- and multivariate-adjusted relationship between ED and mortality.

| HR* for outcome associated with degree of ED (95% CI) |

HR† for outcome associated with binary ED variable (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of Death | Minimal | Moderate | Complete | P-Value Trend | Moderate/Complete | P-Value |

| Age-adjusted | ||||||

| Cancer | 0.82 (0.50–1.35) | 0.79 (0.40–1.57) | 1.44 (0.92–2.24) | .18 | 1.30 (0.89–1.90) | .18 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.03 (0.63–1.68) | 1.80 (1.06–3.04) | 1.93 (1.26–2.96) | <.001 | 1.87 (1.32–2.64) | <.001 |

| Other | 1.17 (0.69–2.01) | 0.79 (0.35–1.78) | 2.23 (1.39–3.58) | .02 | 1.64 (1.11–2.45) | .01 |

| All-Cause | 0.98 (0.74–1.32) | 1.14 (0.79–1.64) | 1.82 (1.41–2.35) | <.001 | 1.60 (1.29–1.98) | <.001 |

| Multivariate-adjusted ‡ | ||||||

| Cancer | 0.76 (0.47–1.26) | 0.71 (0.36–1.41) | 1.12 (0.71–1.77) | .73 | 1.08 (0.74–1.60) | .68 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.94 (0.57–1.57) | 1.51 (0.89–2.57) | 1.35 (0.87–2.10) | .07 | 1.43 (1.00–2.05) | .05 |

| Other | 0.97 (0.56–1.68) | 0.66 (0.29–1.50) | 1.5 (0.92–2.45) | .34 | 1.25 (0.83–1.89) | .28 |

| All-Cause | 0.88 (0.65–1.18) | 0.98 (0.68–1.41) | 1.31 (1.00–1.70) | .05 | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | .04 |

Reference group: men with ED status = none.

Reference group: men with ED status = none or minimal.

Adjusted for age, body mass index as continuous variables, and the following as categorical variables: alcohol consumption (< 1, 1, and 2+ drinks/day), calories expended in physical activity (none, < 200 kcal/day, and ≥ 200 kcal/day), current smoking, self-assessed health (excellent, very good, good, fair/poor), and self-reported chronic disease (heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes). Sample size in multivariate-adjusted models is 1,635.

Table 2 also shows the association of ED with mortality in multivariate-adjusted models. Deaths due to cancer or other causes showed no evidence of an association with ED. In contrast, death due to CVD and all causes were significantly associated with ED. HRs for moderate/complete ED compared with none/minimal ED were 1.26 (95% CI, 1.01–1.57) for all-cause mortality and 1.43 (95% CI, 1.00–2.05) for CVD mortality. When tested for trend, evidence for a dose-response in these multivariate models was statistically significant for all-cause mortality although relatively weak.

We performed a sensitivity analysis that examined whether self-assessed ED, using the single item measured at the first follow-up, predicted all-cause mortality. The multivariate-adjusted HR associated with ED at the first follow-up was 1.29, with a wide confidence interval (95% CI, 0.85–1.96) due to the fact that this analysis included 948 subjects and only 119 deaths over 7 y of follow-up.

To put these findings in context, Table 3 displays HRs for all variables included in the multivariate models for all-cause and CVD mortality. The HR for all-cause mortality associated with ED was smaller than most conventional CVD risk factors. However, the HR for CVD mortality associated with ED was comparable to a number of conventional risk factors, such as BMI, diabetes, and hypertension.

TABLE 3.

Multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios* associated with risk factors for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

| All-cause |

Cardiovascular |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value |

| Moderate/complete ED (vs. none/minimal) | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) | .04 | 1.43 (1.00–2.05) | .05 |

| Age (10-y increase) | 2.78 (2.37–3.26) | <.001 | 3.13 (2.37–4.13) | <.001 |

| Body mass index (per SD increase) | 1.02 (0.91–1.13) | .75 | 1.10 (0.92–1.30) | .30 |

| 2+ alcohol drinks/day (vs. <1 drink/day) | 1.41 (1.08–1.84) | .01 | 0.90 (0.56–1.45) | .66 |

| Low physical activity (vs. high) | 1.27 (0.89–1.81) | .19 | 1.03 (0.57–1.88) | .92 |

| Current smoking | 1.97 (1.56–2.49) | <.001 | 1.87 (1.27–2.77) | .002 |

| Fair/poor health (vs. excellent) | 1.98 (1.34–2.93) | <.001 | 1.91 (1.05–3.50) | .04 |

| Heart disease | 1.90 (1.48–2.44) | <.001 | 2.84 (1.95–4.13) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.43 (1.15–1.78) | .002 | 1.43 (1.00–2.05) | .05 |

| Diabetes | 1.95 (1.47–2.59) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.03–2.56) | .04 |

Hazard ratios obtained from proportional hazards regression models of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality that included all of the variables listed in the table.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of 40–70 year-old men followed for 15 years, ED is positively associated with all-cause and CVD mortality in age- and multivariate-adjusted models. Thus, the hypothesis that any observed association between all-cause mortality and ED would be explained by the presence of an association of ED with CVD death and a lack of or inconsistent association with other causes (e.g., cancer or “other” mortality) was confirmed. In models adjusted for several strong confounding influences, men with ED have a 26% higher risk of all-cause mortality and a 43% higher risk of death due to CVD, compared to men without ED. In this study ED is as strongly associated with CVD mortality as some prominent risk factors for CVD. This is consistent with other studies that have examined ED as a predictor of incident CVD.32, 33

ED has been shown to predict a composite end-point of various adverse cardiac events in both low32, 35 and high34, 55 cardiovascular risk populations. In addition, in community-dwelling men, ED was associated with an approximately 80% higher risk of subsequent coronary artery disease.33 The association of ED with coronary artery disease in that study was particularly strong among younger men; this is unlike the current study, in which the association between ED and CVD death was consistent across age groups. Studies of the association between ED and mortality are limited to the PCPT. In the placebo arm of the PCPT,32 all-cause mortality was related to incident ED with HR of 1.14 (not statistically significant). The magnitude of this estimate from PCPT is only slightly smaller than that observed in this report. The lack of significance reported could be due to the fact that PCPT follow-up was shorter (7 years in PCPT vs. 15 years in the present study) and fewer deaths were observed (174 in PCPT vs. 371 in the present study).

Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by impaired nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, precedes the development of atherosclerotic lesions and has been suggested as an important link between ED and CVD.8, 11, 19–24 Penile erection involves active relaxation of the cavernosal arteries accompanied by passive restriction of venous outflow from the penis. These actions are mediated by the activation of nitric oxide (NO)-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway. Additionally, NO mediates many of the antiatherogenic functions of the arterial endothelium, including its effects on inflammation, vascular smooth muscle proliferation, and platelet aggregation.56 The presence of arteriogenic ED in men may be a strong indicator of the presence of atherosclerotic disease in other parts of the body. This is confirmed in our study. Studies showing that ED is predictive of the development of CVD32, 34, 35 as well as those showing the presence of increased carotid intima-media thickness in men with ED but no clinical evidence of atherosclerosis provide additional support for this hypothesis.57 The penile corpora may be more susceptible to the consequences of reduced vasodilation and blood flow reserve than the heart or brain given the smaller diameter of the penile arteries.31 In addition, the peripheral cavernosal arteries are end arteries, and thus do not have the ability to form collaterals to compensate for decreased blood flow, as does the heart.58 Thus, loss of vasodilation may be recognized earlier in the microvascular penile bed than in coronary arteries.

Limitations to the current study should be acknowledged. Perhaps the most important limitation concerns the measurement of ED. The ED variable used in this report was derived from the gold-standard self-assessment obtained at the first follow-up visit. This self-assessment was not included at baseline. Nonetheless, in our sensitivity analysis, we showed that the HR for all-cause mortality using the derived ED measure (HR = 1.26) was very similar to the estimated HR using the gold-standard self-assessment measured at the first follow-up (HR = 1.29). This supports the use of the derived ED variable used in this analysis. Another concern is that MMAS included mostly white men of higher socioeconomic status, so these results may not be generalizable to more diverse populations. However, MMAS was representative of the greater Boston, MA male population at the time of sampling59 and the distribution of the MMAS causes of death are consistent with the leading causes of death for the MA population at the midpoint of study (1996).60 Although the low (52%) response rate at baseline is cause for concern, a telephone survey of 206 non-respondents to MMAS41 showed that while non-respondents were older, less likely to report cancer or heart disease, and more likely to report their health as fair or poor compared to the entire cohort, there were no differences in the prevalence of diabetes, high blood pressure, or restriction in activity due to poor health. Finally, this study did not include assessments of other known CVD risk factors such as family history of CVD or diabetes, fasting glucose, and inflammation and self-reports of chronic disease have their limitations.

These limitations must be considered in light of the strengths of this study. These include a random, population-based sample of generally healthy, well-characterized men from a defined geographic area, the ability to statistically adjust for a number of factors that could confound the association between ED and mortality, the length of follow-up and the relatively sizable number of events, and the examination of both all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Furthermore, we were able to update ED exposure data, allowing for more precise estimation of potentially modest associations.

The findings from this study and others have major clinical and public health implications. Since the introduction of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, awareness of ED has increased substantially. Thus, discussions between patients and physicians centered on ED and sexual health should be easier to initiate, particularly if these topics are contextualized as relating to potentially serious medical conditions. The assessment of ED is very straightforward and can be done efficiently by simply asking the about a patient's ED status.46 The present findings emphasize the need for primary care physicians and other health care providers to pay particular attention to the cardiovascular risk profiles of their patients with ED.9, 61 If patients present with ED, current recommendations9, 61 – which our study reinforce by linking ED to cardiovascular mortality and showing that ED predicts mortality as strongly as established cardiovascular risk factors – indicate that they should be screened and perhaps treated for cardiovascular disease. Although it is difficult to estimate with currently available data how the implementation of these guidelines would improve survival, these data provide evidence that the impact could be substantial.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the following grants: AG 04673 from the National Institute on Aging; DK 44995, DK 51345 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders; and an unrestricted educational grant to NERI from Bayer Healthcare. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation/approval of the manuscript. The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Rosen reports that he serves as a consultant to Bayer-Schering, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer. Dr. Ganz has reports that he serves as a consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, and Pfizer. Dr. Hall is a former employee of and former consultant to GlaxoSmithKline, but has no equity interest in GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. The American journal of medicine. 2007;120:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aytaç IA, McKinlay JB, Krane RJ. The likely worldwide increase in erectile dysfunction between 1995 and 2025 and some possible policy consequences. BJU Int. 1999;84:50–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].NIH Consensus Conference Impotence. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Impotence. Jama. 1993;270:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, et al. Erectile dysfunction and coronary risk factors: prospective results from the Massachusetts male aging study. Prev Med. 2000;30:328–38. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rosen RC, Wing R, Schneider S, Gendrano N., 3rd Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction: the role of medical comorbidities and lifestyle factors. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2005;32:403–17. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rosen RC, Friedman M, Kostis JB. Lifestyle management of erectile dysfunction: the role of cardiovascular and concomitant risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:76M–79M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Billups KL. Sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: integrative concepts and strategies. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:57M–61M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Billups KL, Bank AJ, Padma-Nathan H, Katz SD, Williams RA. Erectile dysfunction as a harbinger for increased cardiometabolic risk. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:236–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Greenstein A, Chen J, Miller H, Matzkin H, Villa Y, Braf Z. Does severity of ischemic coronary disease correlate with erectile function? Int J Impot Res. 1997;9:123–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kloner RA. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular risk factors. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2005;32:397–402. v. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jackson G. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. International journal of clinical practice. 1999;53:363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, et al. Association between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Role of coronary clinical presentation and extent of coronary vessels involvement: the COBRA trial. European heart journal. 2006;27:2632–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, et al. Common grounds for erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Current opinion in urology. 2004;14:361–5. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200411000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Montorsi F, Briganti A, Salonia A, et al. Erectile dysfunction prevalence, time of onset and association with risk factors in 300 consecutive patients with acute chest pain and angiographically documented coronary artery disease. Eur Urol. 2003;44:360–4. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00305-1. discussion 64–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Montorsi P, Montorsi F, Schulman CC. Is erectile dysfunction the “tip of the iceberg” of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur Urol. 2003;44:352–4. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Morley JE, Korenman SG, Kaiser FE, Mooradian AD, Viosca SP. Relationship of penile brachial pressure index to myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents in older men. The American journal of medicine. 1988;84:445–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ponholzer A, Temml C, Obermayr R, Wehrberger C, Madersbacher S. Is erectile dysfunction an indicator for increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke? Eur Urol. 2005;48:512–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.05.014. discussion 17–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ganz P. Erectile dysfunction: pathophysiologic mechanisms pointing to underlying cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:8M–12M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guay AT. ED2: erectile dysfunction = endothelial dysfunction. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:453–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Guay AT. Relation of endothelial cell function to erectile dysfunction: implications for treatment. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:52M–56M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jones RW, Rees RW, Minhas S, Ralph D, Persad RA, Jeremy JY. Oxygen free radicals and the penis. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2002;3:889–97. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Maas R, Schwedhelm E, Albsmeier J, Boger RH. The pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction related to endothelial dysfunction and mediators of vascular function. Vasc Med. 2002;7:213–25. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm429ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Solomon H, Man JW, Jackson G. Erectile dysfunction and the cardiovascular patient: endothelial dysfunction is the common denominator. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2003;89:251–3. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.3.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glasser DB, Rimm EB. A prospective study of risk factors for erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006;176:217–21. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00589-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Derby CA, Mohr BA, Goldstein I, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, McKinlay JB. Modifiable risk factors and erectile dysfunction: can lifestyle changes modify risk? Urology. 2000;56:302–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fung MM, Bettencourt R, Barrett-Connor E. Heart disease risk factors predict erectile dysfunction 25 years later: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43:1405–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, et al. Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet. 2005;366:218–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jackson G, Padley S. Erectile dysfunction and silent coronary artery disease: abnormal computed tomography coronary angiogram in the presence of normal exercise ECGs. International journal of clinical practice. 2008;62:973–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, et al. The artery size hypothesis: a macrovascular link between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:19M–23M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Probstfield JL, Moinpour CM, Coltman CA. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. Jama. 2005;294:2996–3002. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Inman BA, Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, et al. A population-based, longitudinal study of erectile dysfunction and future coronary artery disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009;84:108–13. doi: 10.4065/84.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gazzaruso C, Solerte SB, Pujia A, et al. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular events and death in diabetic patients with angiographically proven asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a potential protective role for statins and 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:2040–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Bosch JL, et al. Erectile dysfunction prospectively associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population: results from the Krimpen Study. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:92–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fox CS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Temporal trends in coronary heart disease mortality and sudden cardiac death from 1950 to 1999: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:522–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136993.34344.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kuller L, Cooper M, Perper J. Epidemiology of sudden death. Arch Intern Med. 1972;129:714–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Podrid PJ, Myerburg RJ. Epidemiology and stratification of risk for sudden cardiac death. Clinical cardiology. 2005;28:I3–11. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960281303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].O'Donnell AB, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. The health of normally aging men: The Massachusetts Male Aging Study (1987–2004) Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:975–84. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].McKinlay S, Kipp D, Johnson P, Downey K, Carelton R. A field approach for obtaining physiological measures in surveys of general populations: response rates, reliability and costs. Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Health Survey Research Methods; Washington, DC. 1984. pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- [41].McKinlay JB, Feldman HA. Age-related variation in sexual activity and interest in normal men: Results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. In: Rossi AS, editor. Sexuality Across the Lifecourse: Proceedings of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Mid-Life Development, 1992; New York, NY: University of Chicago Press; 1994. pp. 261–85. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kleinman KP, Feldman HA, Johannes CB, Derby CA, McKinlay JB. A new surrogate variable for erectile dysfunction status in the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:71–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Derby CA, Araujo AB, Johannes CB, Feldman HA, McKinlay JB. Measurement of erectile dysfunction in population-based studies: the use of a single question self-assessment in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Int J Impot Res. 2000;12:197–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH. Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].O'Leary MP, Fowler FJ, Lenderking WR, et al. A brief male sexual function inventory for urology. Urology. 1995;46:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80304-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].O'Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB. The validity of a single-question self-report of erectile dysfunction. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Araujo AB, Johannes CB, Feldman HA, Derby CA, McKinlay JB. Relation between psychosocial risk factors and incident erectile dysfunction: prospective results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:533–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bilgrad R. National Death Index Plus: Coded Causes Of Death Supplement to the National Death Index User's Manual. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Araujo AB, Kupelian V, Page ST, Handelsman DJ, Bremner WJ, McKinlay JB. Sex steroids and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1252–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, et al. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:270–7. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Doody MM, Hayes HM, Bilgrad R. Comparability of national death index plus and standard procedures for determining causes of death in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II - The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Scientific Publications No. 82. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) (Series B).J Royal Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Travison TG, Shabsigh R, Araujo AB, Kupelian V, O'Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. The natural progression and remission of erectile dysfunction: results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 2007;177:241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.108. discussion 46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gazzaruso C, Giordanetti S, De Amici E, et al. Relationship between erectile dysfunction and silent myocardial ischemia in apparently uncomplicated type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation. 2004;110:22–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133278.81226.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sessa WC. eNOS at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2427–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bocchio M, Scarpelli P, Necozione S, et al. Intima-media thickening of common carotid arteries is a risk factor for severe erectile dysfunction in men with vascular risk factors but no clinical evidence of atherosclerosis. J Urol. 2005;173:526–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000148890.83659.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Angus JA. Arteriolar structure and its implications for function in health and disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1994;3:99–106. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].U.S. Census Bureau [Accessed January 1, 2000];Census of Population and Housing, Summary Tape File 3C - part 1. 1990 http://venus.census.gov/cdrom/lookup.

- [60].Massachusetts Department of Public Health [Accessed March 1, 2006];Advance Data: Deaths. 1996 http://mass.gov/dph/bhsre/death/96/dth96c6.htm.

- [61].Kostis JB, Jackson G, Rosen R, et al. Sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk (the Second Princeton Consensus Conference) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:85M–93M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]