Abstract

♦ Objective: Residual renal function (RRF) is associated with low oxidative stress in peritoneal dialysis (PD). In the present study, we investigated the relationship between the impact of oxidative stress on RRF and patient outcomes during PD.

♦ Methods: Levels of free radicals (FRs) in effluent from the overnight dwell in 45 outpatients were determined by electron spin resonance spectrometry. The FR levels, clinical parameters, and the level of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine were evaluated at study start. The effects of effluent FR level on technique and patient survival were analyzed in a prospective cohort followed for 24 months.

♦ Results: Levels of effluent FRs showed significant negative correlations with daily urine volume and residual renal Kt/V, and positive correlations with plasma β2-microglobulin and effluent 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine. A highly significant difference in technique survival (p < 0.05), but not patient survival, was observed for patients grouped by effluent FR quartile. The effluent FR level was independently associated with technique failure after adjusting for patient age, history of cardiovascular disease, and presence of diabetes mellitus (p < 0.001). The level of effluent FRs was associated with death-censored technique failure in both univariate (p < 0.001) and multivariate (p < 0.01) hazard models. Compared with patients remaining on PD, those withdrawn from the modality had significantly higher levels of effluent FRs (p < 0.005).

♦ Conclusions: Elevated effluent FRs are associated with RRF and technique failure in stable PD patients. These findings highlight the importance of oxidative stress as an unfavorable prognostic factor in PD and emphasize that steps should be taken to minimize oxidative stress in these patients.

Keywords: Free radicals, electron spin resonance, dialysate, oxidative stress, residual renal function, α-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone

Preservation of residual renal function (RRF) improves survival in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients (1-4). Residual renal function is important for the clearance of middle molecules (5) and for fluid and sodium removal (6). Moreover, preservation of RRF is associated with lower oxidative and carbonyl stress in PD patients. Previous studies have shown that the residual glomerular filtration rate is independently associated with both plasma and peritoneal effluent levels of the well-characterized advanced glycation endproducts Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine and Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine (7). Blood levels of free malondialdehyde and lipid hydroperoxide decline with the total weekly Kt/V urea and with urinary Kt/V, but not with peritoneal Kt/V. The total weekly Kt/V urea and urinary Kt/V have been associated with free malon-dialdehyde and lipid hydroperoxide independently of sex, nutrition or inflammation status, and peritoneal permeability (8). Plasma levels of advanced oxidation protein products and pentosidine were significantly lower in patients who maintained a daily urine volume of 300 mL or more than in groups with a daily urine volume below 300 mL (9).

Oxidative and carbonyl stress are both reported to be cardiovascular risk factors (10,11), and cardiovascular disease is a major cause of death in PD patients. Use of solutions low in glucose degradation products (GDPs) results in significant improvements in technique and patient survival in patients undergoing PD (12). In a multicenter randomized prospective study involving 69 PD patients, monthly RRF changes were significantly different in patients receiving low-GDP fluids than in those receiving standard fluids, regardless of whether patients were taking an angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (13). However, there are few useful markers for predicting the clinical prognosis of patients undergoing PD.

Recent advances in medical engineering have made it possible to use the spin-trapping method, which uses electron spin resonance (ESR), to identify and quantify various species of free radicals in specific reactions. In a previous study, the ESR signals of post-hemodialysis (HD) sera were demonstrated to be significantly weaker than those of pre-HD sera, and no significant difference in ESR signal was observed between post-HD and healthy sera (14). The hydroxyl radical signal intensity had a strong correlation with the serum ferritin level in HD patients taking a high dose of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (15). A recent in vitro study using ESR with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide and 3,5-dibromo-4-nitrosobenzene-sulfonic acid as spin-trapping agents indicated that free radicals are generated through a nonenzymatic reaction between methylglyoxal and hydrogen peroxide (16). However, no study has so far used ESR and spin-trapping to evaluate the free radicals present in PD patients as a potential biomarker for prognosis.

Based on the foregoing studies, we hypothesized that the level of free radicals in dialysate effluents might reflect RRF and predict technique and overall patient survival in PD patients. We tested this hypothesis by the ESR method, using a spin-trapping agent to determining dialysate free radicals in a prospective cohort study investigating the relationship between the level of effluent free radicals and technique and patient survival in PD patients.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENT SELECTION

Our study was designed as an objective prospective single-center study to be conducted over a 24-month observational period. It enrolled 45 outpatients of the Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital who were receiving PD. Each patient gave informed consent before participation, and the local ethics committee gave approval for the study, which is registered to the Clinical Trial Registry of Japan’s University Hospital Medical Information Network (number UMIN000003138). Demographic characteristics, clinical data, and comorbidities [cardio-cerebrovascular disease (CVD), including ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, and strokes; hypertension; diabetes mellitus] were all recorded at study start. All patients with hypertension received antihypertensive drugs, including calcium antagonists and angiotensin blockers. Of the 45 patients, 3 were undergoing once-weekly HD in addition to PD. None of the patients changed either their dialysis regimen or solutions during the initial 2 months of the study. None had peritonitis at study start. The endpoint of the study was withdrawal from PD or overall mortality. The effects of baseline clinical and comorbidity variables on the endpoint were analyzed for statistical significance.

EFFLUENT COLLECTION

Peritoneal effluent (20 mL) was collected from an overnight dwell (2.27% glucose for 8 hours). Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes, after which aliquots of the supernatants were stored at -80°C until assay.

MEASUREMENT OF FREE RADICALS IN PERITONEAL EFFLUENTS BY ESR SPECTROMETRY

Carbon-centered radicals in dialysate samples were detected by ESR spectrometry using a spin-trap reagent (17). The test sample (150 μL) was combined with 50 μL of 1 mmol/L α-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone [PBN, molecular weight 177.2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)] dissolved in 50% ethanol. The ESR spectra were monitored using a JES-FR spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) for 3 minutes after the addition of 50 μL of the PBN solution to 150 μL of the test solution (final PBN concentration: 250 μmol/L). Relative signal intensities were determined as integration values for the spectrum of the first-detected doublet spin adduct (Is) divided by that of an internal standard, MnO (Im). The Is/Im for the control (unused) solution was subtracted from that for the sample solution. That value, multiplied by 10, was defined as the level of free radicals in each patient. According to our previously established protocol (18), the ESR settings were power, 4 mW; magnetic field, 335.6 ± 5 mT; modulation frequency, 9.41 GHz; modulation amplitude, 0.5×0.1 mT; response time, 0.1 s; sweep time, 1 minute; temperature, room temperature. To confirm that the ESR signal was proportional to the spin-trap adduct concentration, a calibration curve was constructed after exposure of the spin trap to increasing concentrations of free radicals.

DETERMINATION OF EFFLUENT 8-HYDROXY-2′-DEOXYGUANOSINE

The levels of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in peritoneal effluents were measured using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described (19).

PERITONEAL EQUILIBRATION TEST

Peritoneal solute transport was assessed using the fast peritoneal equilibration test (PET) as previously described (20). In brief, 2.5% glucose PD fluid was instilled intraperitoneally after intra-abdominal fluid had been drained. The creatinine (Cr) level of the peritoneal effluent obtained 4 hours after instillation (D) was divided by that of plasma (P) to obtain the D/P Cr value. Peritoneal transport status was assessed as a categorical variable according to the four groups of D/P Cr values (low, <0.50; low-average, 0.50 - 0.64; high-average, 0.65 - 0.80; high, ≥0.81) defined by Twardowski (21).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The statistical analysis was performed using the JMP software package (release 6: SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous parametric data, median and interquartile range for continuous nonparametric data, and frequencies for categorical data. A linear regression analysis of the data at baseline was performed using the least-squares method. A Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank statistic were used to explore the effect of free radical levels on technique and patient survival. The Cox proportional hazards model of univariate and multivariate analysis was used to test the significance of demographic, clinical, and laboratory data, including the levels of effluent free radicals and effluent 8-OHdG. Technique survival times were censored only when patients died, underwent transplantation, were transferred to HD, were lost to follow-up monitoring, or completed the study. Patient survival times were censored when patients underwent transplantation, were transferred to HD, were lost to follow-up monitoring, or completed the study. The durations of technique and patient survival were calculated from the date of effluent collection.

RESULTS

ESR SPECTRA FOR CONTROL AND SAMPLE DIALYSIS EFFLUENT

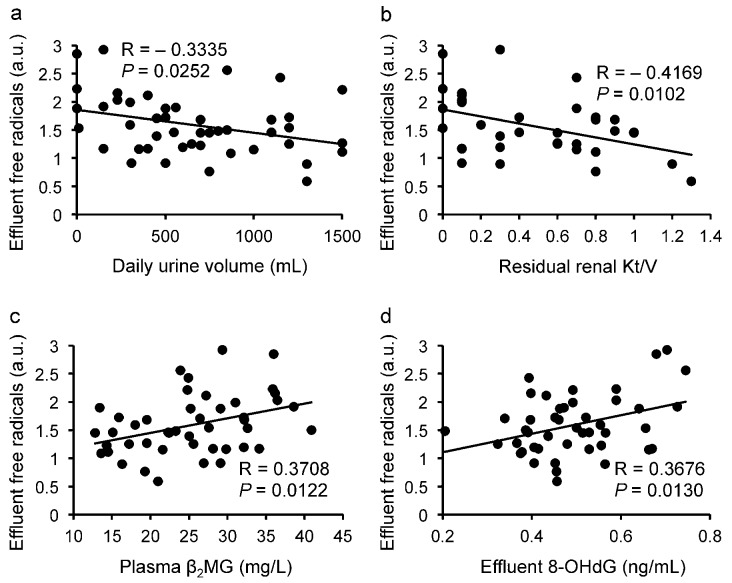

To identify the carbon-centered radicals, ESR measurements were taken using the spin-trapping reagent, PBN. Figure 1 shows the three doublet ESR spectra of the control or sample solution with the added PBN. The peaks at each end of the ESR images correspond to Mn2+ in MnO. Faint signals were observed in the mixed solution without dialysate (data not shown).

Figure 1.

— Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra of carbon-centered radicals (open triangles) for sample and control (unused) solutions, and for Mn2+ as an internal control (filled triangles). The levels of relative signal intensity were determined as integration values for the spectrum of the first spin adduct of three doublet spectra (Is) divided by that of an internal standard MnO (Im). The Is/Im value for the sample solution subtracted from that of the control solution was defined as the level of free radicals. The ESR spectra were monitored for 3 minutes after 50 μL 1 mmol/L α-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) had been added to 150 μL of the test solution (final PBN concentration: 250 μmol/L).

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

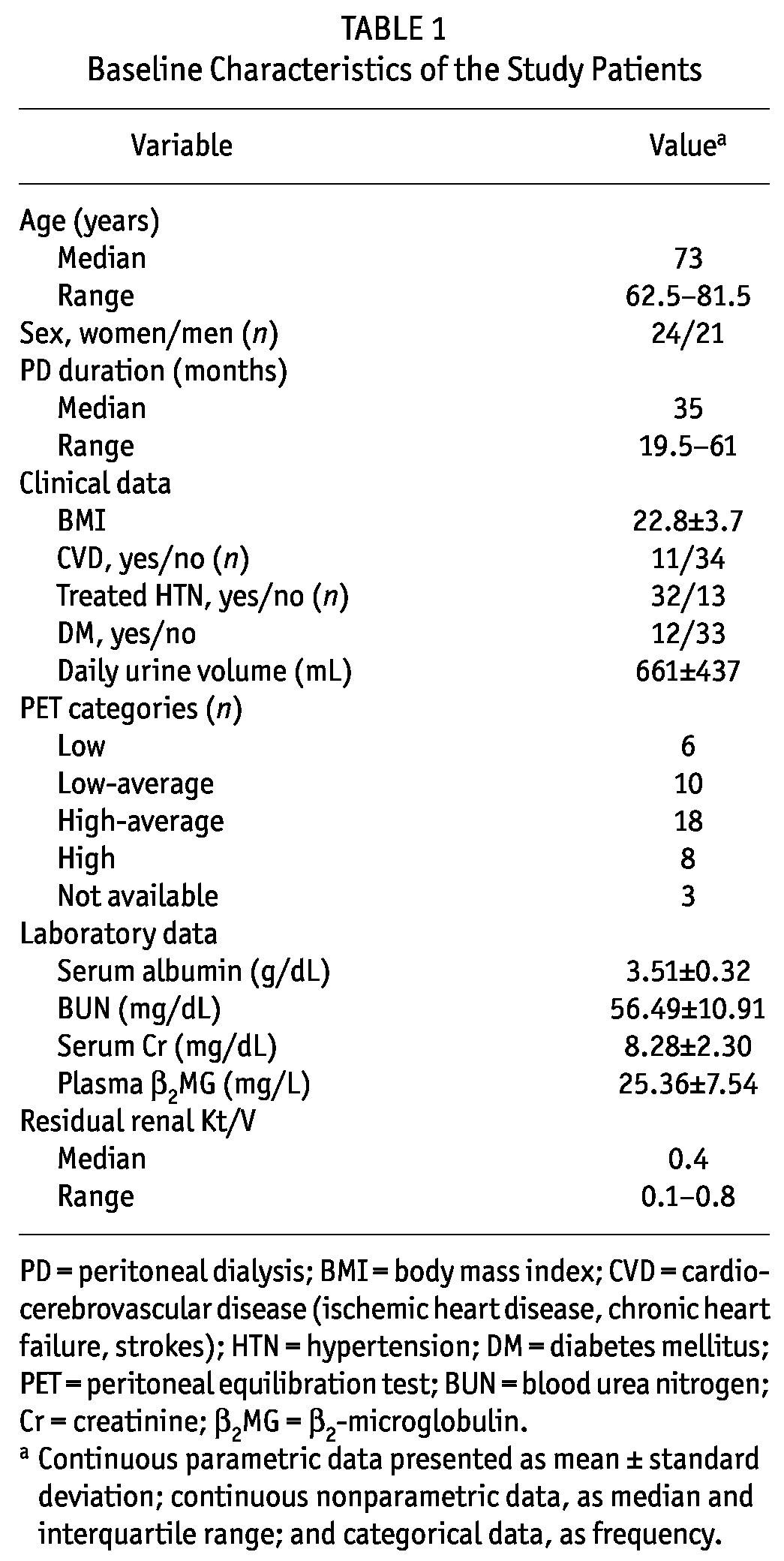

Table 1 summarizes the basal clinical characteristics of the study population. The underlying cause of kidney disease was chronic glomerulonephritis in 19 patients (42.2%), diabetic nephropathy in 12 patients (26.6%), hypertensive nephrosclerosis in 9 patients (20.0%), and unidentified in 5 patients (11.1%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Patients

CORRELATIONS WITH LEVELS OF EFFLUENT FREE RADICALS

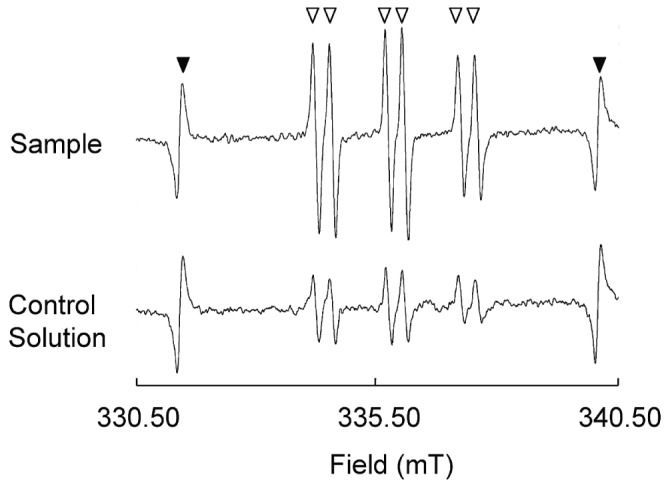

We observed significant negative correlations for the level of effluent carbon-centered free radicals detected as PBN adducts with daily urine volume [R = -0.3335, p = 0.0252, Figure 2(a)] and with residual renal Kt/V [R = -0.4169, p = 0.0102, Figure 2(b)]. In addition, the level of effluent free radicals significantly correlated with plasma β2-microglobulin [β2MG: R = 0.3708, p = 0.0122, Figure 2(c)] and effluent 8-OHdG [R = 0.3676, p = 0.0130, Figure 2(d)] at baseline, the latter being a known marker of oxidative stress in peritoneal effluent (22). Plasma β2MG has been suggested to be a potential predictor for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in PD patients in Japan (23); however, no patients in the present study developed that disease during the study period.

Figure 2.

— Correlation between the effluent free radical level and (a) daily urine volume, (b) residual renal Kt/V, (c) plasma β2-microglobulin (β2MG), and (d) effluent 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG). We observed significant negative correlations with daily urine volume (R = -0.3335, p = 0.0252) and residual renal Kt/V (R = -0.4169, p = 0.0102), and significant positive correlations with plasma β2MG (R = 0.3708, p = 0.0122) and effluent 8-OHdG (R = 0.3676, p = 0.0130). a.u. = arbitrary unit.

No significant correlations were found for the level of free radicals with patient age, PD duration, body mass index, CVD history, PET category, serum albumin, serum creatinine, or blood urea nitrogen. Compared with nondiabetic patients, those with diabetes had similar levels of effluent free radicals [0.155 ± 0.051 au (arbitrary units) vs 0.160 ± 0.054 au]. Compared with patients not having CVD, those with CVD had similar levels of effluent free radicals (0.163 ± 0.051 au vs 0.158 ± 0.054 au). Levels of effluent 8-OHdG were found to be similar in patients with and without diabetes and also in patients with and without CVD (0.501 ± 0.121 ng/mL vs 0.491 ± 0.118 ng/mL and 0.539 ± 0.088 ng/mL vs 0.479 ± 0.124 ng/mL respectively).

KAPLAN-MEIER SURVIVAL ANALYSIS BY LEVEL OF EFFLUENT FREE RADICALS

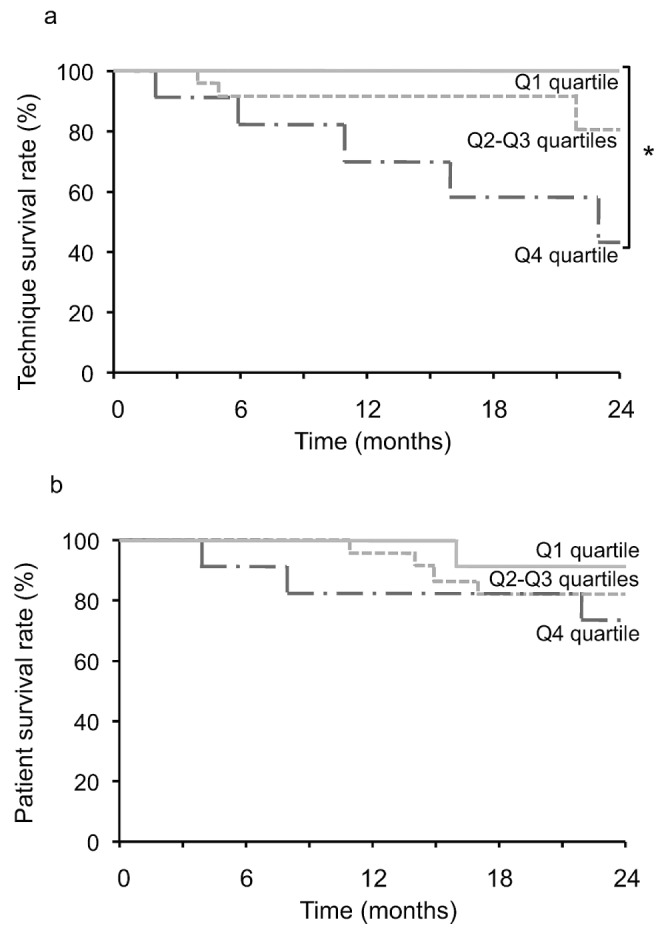

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis for both technique and patient survival. We observed a highly significant difference in death-censored technique survival when patients were divided into groups by quartile level of effluent free radicals [log-rank p = 0.0120, Figure 3(a)]. The 2-year event-free technique survival probabilities were 100.0% for quartile Q1, 80.0% for quartiles Q2 and Q3, and 43.3% for quartile Q4. By contrast, we observed no significant difference in overall patient survival when patients were divided into groups by quartile level of effluent free radicals [log-rank p = 0.5241, Figure 3(b)].

Figure 3.

— Kaplan-Meier curves for (a) technique survival (* log-rank p = 0.0120) and (b) overall patient survival (log-rank p = 0.5241) in patients (n = 45) divided into groups by quartile (Q) of effluent free radicals.

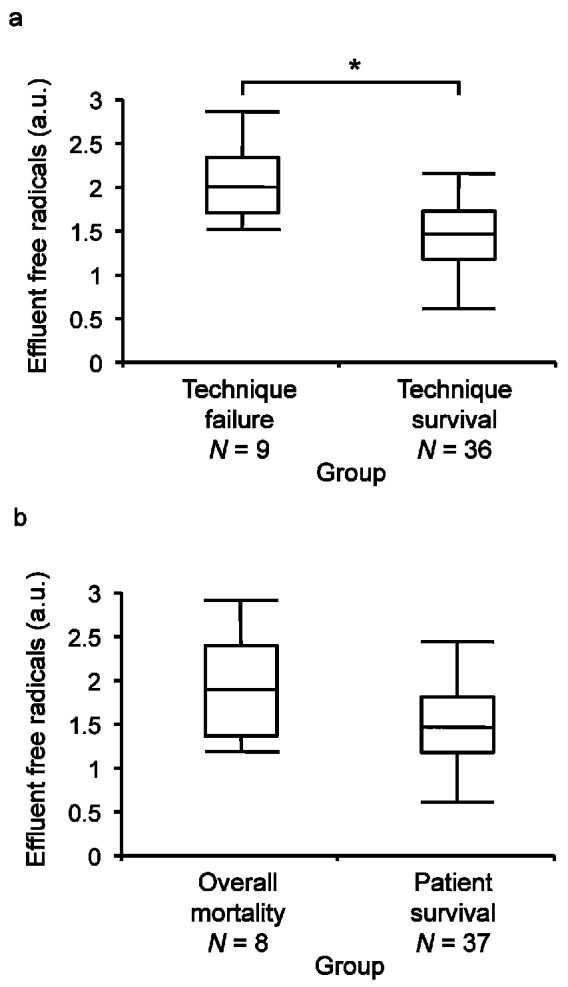

During the 24 months of follow-up, 9 patients withdrew from PD, and 8 died. All 9 patients who withdrew were transferred to HD and were considered to be “technique failures.” The causes for transfer to HD were ultrafiltration failure (n = 6), peritonitis (n = 2), and hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1). Compared with the remaining 36 patients (the “technique survival” group), the “technique failure” group of 9 patients had significantly higher levels of effluent free radicals [2.05 ± 0.42 au vs 1.47 ± 0.49 au, p = 0.0021, Figure 4(a)]. Of the 8 deaths, 5 were attributed to cardio-cerebrovascular causes, and 3, to non-cardio-cerebrovascular causes. Those 8 patients were considered to be the “overall mortality” group. Compared with the remaining 37 patients (the “patient survival” group), the 8 patients in the “overall mortality” group had higher levels of effluent free radicals, but the difference was not significant [1.91 ± 0.60 au vs 1.52 ± 0.49 au, p = 0.0798, Figure 4(b)].

Figure 4.

— Box and line plots show effluent levels of free radicals (a) for 9 patients who abandoned peritoneal dialysis (PD) during 24 months of follow-up (“technique failure”) compared with 36 patients who remained on PD (“technique survival,” * Mann-Whitney p = 0.0021); and (b) for 8 patients who died during 24 months of follow-up (“overall mortality”) compared with 37 patients who survived (“patient survival,” Mann-Whitney p = 0.0798). Boxes denote medians and 25th and 75th percentiles. Lines mark the 5th and 95th percentiles. a.u. = arbitrary unit.

MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS FOR PREDICTORS OF THE ENDPOINT

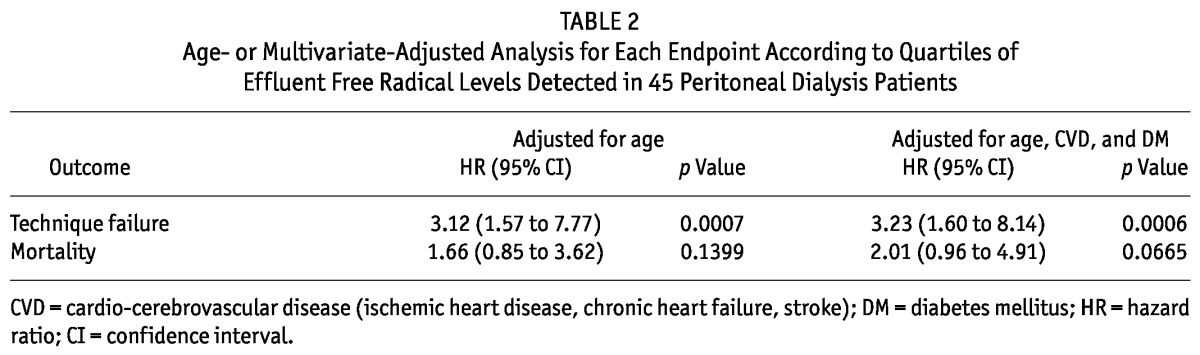

The Cox proportional hazards model was applied to the entire study population to evaluate the risk for technique failure or mortality (Table 2). The presence of increased effluent free radicals was a significant risk for technique failure in the age-adjusted model [hazard ratio (HR): 3.12; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.57 to 7.77; p = 0.0007] and even in the model adjusted for age, presence of CVD, and presence of diabetes mellitus (HR: 3.23; 95% CI: 1.60 to 8.14; p = 0.0006). By contrast, the presence of increased levels of effluent free radicals was not a significant risk for mortality in either model (respectively, HR: 1.66; 95% CI: 0.85 to 3.62; p = 0.1399; and HR: 2.01; 95% CI: 0.96 to 4.91; p = 0.0665).

TABLE 2.

Age- or Multivariate-Adjusted Analysis for Each Endpoint According to Quartiles of Effluent Free Radical Levels Detected in 45 Peritoneal Dialysis Patients

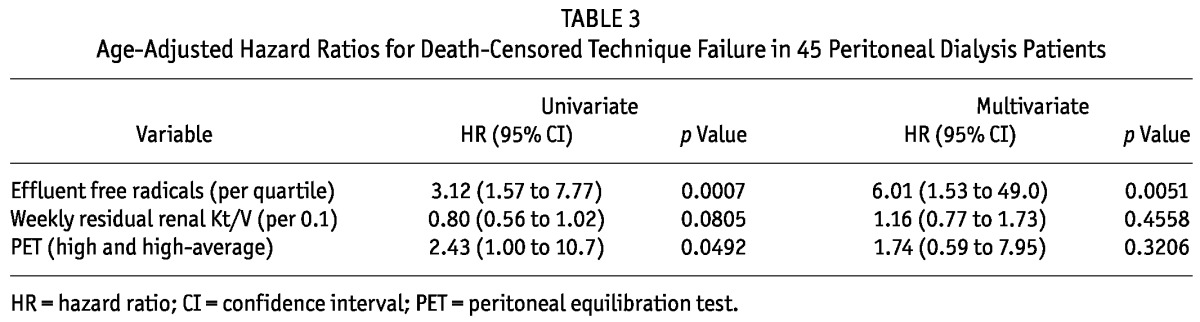

Next, a multivariate analysis was carried out to adjust event-free times for levels of effluent free radicals, residual renal Kt/V, and high permeability by PET (Table 3). Although increased levels of effluent free radicals and high permeability by PET were associated with death-censored technique survival in the univariate analysis, the only factor found to be independently associated with death-censored technique failure in a multivariate analysis was an increased level of effluent free radicals (per quartile—HR: 3.12; 95% CI: 1.57 to 7.77; p = 0.0007).

TABLE 3.

Age-Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Death-Censored Technique Failure in 45 Peritoneal Dialysis Patients

DISCUSSION

Our study used ESR spectrometry to quantify levels of free radicals in PD effluents and demonstrated that an elevated level of effluent free radicals is a significant predictor of technique failure in patients undergoing PD. Levels of effluent free radicals were significantly associated with daily urine volume, plasma β2MG, and effluent 8-OHdG.

This report is the first to attempt an analysis of the relationship between effluent free radicals and clinical outcome in PD patients. Szeto et al. reported that dialysate hyaluronan concentration predicts survival in stable PD patients (24). At 24 months of follow-up, the statistical patient survival rates were approximately 91% and 76% for the low and high hyaluronan groups respectively. Those findings are similar to findings in the present study of survival rates of 90.5% and 74.2% respectively for the low and high levels of effluent free radical when patients were divided into two groups (higher and lower than the median level of effluent free radicals). Similarly, high permeability by PET, which is a well-defined clinical factor related to technique failure and mortality (25-27), was shown to be a significant risk factor for death-censored technique failure in an age-adjusted univariate model (HR: 2.43) after level of effluent free radicals (HR: 3.12; Table 3).

One possible explanation for the correlation between the level of effluent free radicals and patient outcome is the association of effluent free radicals and RRF. In the present study, we observed a significant negative correlation between the level of effluent free radicals and daily urine volume or residual renal Kt/V. The relative contribution of RRF, rather than peritoneal clearance, to combined technique and patient survival (3), patient survival (1), quality of life, and adequacy of dialysis (1,3) was reported previously. The re-analysis of the CANUSA study showed that every 250 mL increase in daily urine volume reduced the relative risk of death by 36%, indicating the importance of RRF to the long-term survival of PD patients (1). The current study found that every 250 mL decrease in daily urine volume was associated with an 0.1 au elevation in the level of effluent free radicals, which corresponded, in our cohort, to a 14% increase in the relative risk of death at 24 months of follow-up. That finding suggests that the association between effluent free radicals and RRF affects patient survival.

We measured levels of serum free radicals in 8 samples from this cohort that had been kept frozen. Unexpectedly, we found an inverse correlation between the serum and effluent levels of free radicals in this small population (unpublished data). We observed no correlation between levels of serum free radicals and daily urinary volume or residual renal Kt/V. The elevated free radicals in effluent may therefore be produced locally at the peritoneum. Indeed, cultured peritoneal mesothelial cells spontaneously produce hydrogen peroxide, which can be elevated in the presence of glucose-containing dialysate in vitro (28). Another reason for the discrepancy may have been degeneration of the serum samples because of long-term storage.

Nakayama et al. demonstrated that free radicals, including methyl and other carbon-centered radicals, are generated in a nonenzymatic reaction of methylglyoxal and hydrogen peroxide in vitro (16). The GDPs derived from glucose in peritoneal dialysate include methylglyoxal, glyoxal, formaldehyde, and 3-deoxyglucosone. Methylglyoxal, an extremely toxic GDP with strong oxidative activity, can enhance the production of vascular endothelial growth factor and induce the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. In this context, the levels of free radicals might be higher in effluents than in plasma, although we did not examine levels in plasma. Another study demonstrated peritoneal fibrous thickening in rats treated with methylglyoxal, although peritoneal function was not evaluated in that model (29).

The level of effluent free radicals did not significantly correlate with peritoneal permeability in the current study, but it did significantly correlate with the level of effluent 8-OHdG. That molecule is associated with oxidative DNA damage; it is not a marker of free radicals per se. Because 8-OHdG is known to be a biomarker of oxidative stress in the peritoneum (22,30), we evaluated whether the level of 8-OHdG could predict technique or patient survival. However, we observed no significant difference in technique or patient survival for patients divided into quartiles reflecting their level of 8-OHdG (log-rank p = 0.6712 for technique survival and 0.3142 for patient survival). The level of 8-OHdG was not a good biomarker for predicting outcomes in the current study population (data not shown).

Use of a nitric oxide sensor to take direct measurements of nitric oxide concentrations in peritoneal dialysate has recently been reported (31). To obtain a better comparison of the sensitivity and accuracy of the nitric oxide sensor with ESR signals, it might be necessary to use another spin-trapping agent (such as 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) in conjunction with our method to reduce any possible methodology bias in the study.

The population in the present study consisted of relatively older people than are seen in the usual PD population. The mean age of new patients on dialysis is 66.8 years, and in Japan, the mean age of the entire dialysis patient population is 64.9 years (31). Although the patients in our study were older, age and PD duration did not significantly correlate with levels of effluent free radicals in this population. Further studies in a larger number of patients, including those of different ages, would help to confirm our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Levels of effluent free radicals correlate with RRF. Moreover, elevated levels of effluent free radicals predict death-censored technique failure in stable PD patients. These findings highlight the importance of oxidative stress as an unfavorable prognostic factor in PD patients. Consequently, further studies on the mechanism of peritoneal free radical production are essential to clarify whether reducing intraperitoneal oxidative stress by utilizing free radical scavengers (32,33) or molecular hydrogen (34) can improve the preservation of RRF and technique and overall survival in patients undergoing PD. In the near future, our method of measuring effluent free radicals may be applicable to evaluations of the effects of antioxidant agents on oxidative stress levels in the peritoneum in PD patients.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from The Kidney Foundation, Japan (JKF05-2 to HS and JKFB09-14 to HM). We are grateful to Ms. Kikuko Nozaki for her expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bargman JM, Thorpe KE, Churchill DN. Relative contribution of residual renal function and peritoneal clearance to adequacy of dialysis: a reanalysis of the CANUSA study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:2158–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rocco MV, Frankenfield DL, Prowant B, Frederick P, Flanigan MJ. Risk factors for early mortality in US peritoneal dialysis patients: impact of residual renal function. Perit Dial Int 2002; 22:371–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Termorshuizen F, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, van Manen JG, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT. The relative importance of residual renal function compared with peritoneal clearance for patient survival and quality of life: an analysis of the Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD)-2. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41:1293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang AY, Woo J, Wang M, Sea MM, Sanderson JE, Lui SF, et al. Important differentiation of factors that predict outcome in peritoneal dialysis patients with different degrees of residual renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20:396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bammens B, Evenepoel P, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Removal of middle molecules and protein-bound solutes by peritoneal dialysis and relation with uremic symptoms. Kidney Int 2003; 64:2238–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng LT, Chen W, Tang W, Wang T. Residual renal function and volume control in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract 2006;104:c47–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van de Kerkhof J, Schalkwijk CG, Konings CJ, Cheriex EC, van der Sande FM, Scheffer PG, et al. Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine, Nε-(carboxyethyl)lysine and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in relation to peritoneal glucose prescription and residual renal function; a study in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19:910–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ignace S, Fouque D, Arkouche W, Steghens JP, Guebre-Egziabher F. Preserved residual renal function is associated with lower oxidative stress in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:1685–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furuya R, Kumagai H, Odamaki M, Takahashi M, Miyaki A, Hishida A. Impact of residual renal function on plasma levels of advanced oxidation protein products and pentosidine in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract 2009; 112:c255–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peppa M, Uribarri J, Cai W, Lu M, Vlassara H. Glycoxidation and inflammation in renal failure patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:690–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Descamps-Latscha B, Witko-Sarsat V, Nguyen-Khoa T, Nguyen AT, Gausson V, Mothu N, et al. Advanced oxidation protein products as risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in nondiabetic predialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee HY, Choi HY, Park HC, Seo BJ, Do JY, Yun SR, et al. Changing prescribing practice in CAPD patients in Korea: increased utilization of low GDP solutions improves patient outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:2893–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haag-Weber M, Krämer R, Haake R, Islam MS, Prischl F, Haug U, et al. Low-GDP fluid (Gambrosol Trio) attenuates decline of residual renal function in PD patients: a prospective randomized study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:2288–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagase S, Aoyagi K, Hirayama A, Gotoh M, Ueda A, Tomida C, et al. Favorable effect of hemodialysis on decreased serum antioxidant activity in hemodialysis patients demonstrated by electron spin resonance. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997; 8:1157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirayama A, Nagase S, Gotoh M, Ueda A, Ishizu T, Yoh K, et al. Reduced serum hydroxyl radical scavenging activity in erythropoietin therapy resistant renal anemia. Free Radic Res 2002; 36:1155–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nakayama M, Saito K, Sato E, Nakayama K, Terawaki H, Ito S, et al. Radical generation by the non-enzymatic reaction of methylglyoxal and hydrogen peroxide. Redox Rep 2007; 12:125–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou DS, Hsiao G, Shen MY, Tsai YJ, Chen TF, Sheu JR. ESR spin trapping of a carbon-centered free radical from agonist-stimulated human platelets. Free Radic Biol Med 2005; 39:237–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kakishita M, Nakamura K, Asanuma M, Morita H, Saito H, Kusano K, et al. Direct evidence for increased hydroxyl radicals in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy through angiotensin II type 1a receptor. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2003; 42(Suppl 1):S67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akagi S, Nagake Y, Kasahara J, Sarai A, Kihara T, Morimoto H, et al. Significance of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8:192–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Twardowski ZJ. The fast peritoneal equilibration test. Semin Dial 1990; 3:141–2 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Twardowski ZJ, Nolph KD, Khanna R, Prowant BF, Ryan LP, Moore HL, et al. Peritoneal equilibration test. Perit Dial Bull 1987; 7:138–47 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fukuoka N, Sugiyama H, Inoue T, Kikumoto Y, Takiue K, Morinaga H, et al. Increased susceptibility to oxidant-mediated tissue injury and peritoneal fibrosis in acata-lasemic mice. Am J Nephrol 2008; 8:661–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yokoyama K, Yoshida H, Matsuo N, Maruyama Y, Kawamura Y, Yamamoto R, et al. Serum β2 microglobulin (β2MG) level is a potential predictor for encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2008; 69:121–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szeto CC, Wong TY, Lai KB, Lam CW, Lai KN, Li PK. Dialysate hyaluronan concentration predicts survival but not peritoneal sclerosis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 36:609–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jager KJ, Merkus MP, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Tijssen JG, Stevens P, et al. Mortality and technique failure in patients starting chronic peritoneal dialysis: results of The Netherlands Cooperative Study on the Adequacy of Dialysis. NECOSAD Study Group; Kidney Int 1999; 55:1476–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brimble KS, Walker M, Margetts PJ, Kundhal KK, Rabbat CG. Meta-analysis: peritoneal membrane transport, mortality, and technique failure in peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2591–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rumpsfeld M, McDonald SP, Johnson DW. Higher peritoneal transport status is associated with higher mortality and technique failure in the Australian and New Zealand peritoneal dialysis patient populations. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:271–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shostak A, Pivnik E, Gotloib L. Cultured rat mesothelial cells generate hydrogen peroxide: a new player in peritoneal defense? J Am Soc Nephrol 1996; 7:2371–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hirahara I, Ishibashi Y, Kaname S, Kusano E, Fujita T. Methylglyoxal induces peritoneal thickening by mesenchymal-like mesothelial cells in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:437–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Breborowicz A, Polubinska A, Kupczyk M, Wanic-Kossowka M, Oreopoulos DG. Intravenous iron sucrose changes the intraperitoneal homeostasis. Blood Purif 2009; 28:53–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mochizuki S, Takayama A, Sasaki T, Horike H, Kashihara N, Ogasawara Y, et al. Direct measurement of nitric oxide concentration in CAPD dialysate. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:111–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seo EY, Gwak H, Lee HB, Ha H. Stability of N-acetylcysteine in peritoneal dialysis solution. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Feldman L, Shani M, Efrati S, Beberashvili I, Yakov-Hai I, Abramov E, et al. N-Acetylcysteine improves residual renal function in peritoneal dialysis patients: a pilot study. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:545–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ohsawa I, Ishikawa M, Takahashi K, Watanabe M, Nishimaki K, Yamagata K, et al. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat Med 2007; 13:688–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]