Abstract

♦ Background: The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of oral pioglitazone (PIO) on lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation, and adipokine metabolism in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) patients.

♦ Methods: In this randomized crossover trial, 36 CAPD patients with serum triglyceride levels above 1.8 mmol/L were randomly assigned to receive either oral PIO 15 mg once daily or no PIO for 12 weeks. Then, after a 4-week washout, the patients were switched to the alternative regimen. The primary endpoint was change in serum triglycerides during the PIO regimen compared with no PIO. Secondary endpoints included changes in other lipid levels, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), adipocytokines, and C-reactive protein (CRP).

♦ Results: All 36 CAPD patients (age: 64 ± 11 years; 33% men; 27.8% with diabetes mellitus) completed the study. Comparing patients after PIO and no PIO therapy, we found no significant differences in mean serum triglycerides (3.83 ± 1.49 mmol/L vs 3.51 ± 1.98 mmol/L, p = 0.2). However, mean high-density lipoprotein (0.94 ± 0.22 mmol/L vs 1.00 ± 0.21 mmol/L, p = 0.004) and median total adiponectin [10.34 μg/mL (range: 2.59 - 34.48 μg/mL) vs 30.44 μg/mL (3.47 - 93.41 μg/mL), p < 0.001] increased significantly. Median HOMA-IR [7.51 (1.39 - 45.23) vs 5.38 (0.97 - 14.95), p = 0.006], mean fasting blood glucose (7.31 ± 2.57 mmol/L vs 6.60 ± 2.45 mmol/L, p = 0.01), median CRP [8.78 mg/L (0.18 - 53 mg/L) vs 3.50 mg/L (0.17 - 26.30 mg/L), p = 0.005], and mean resistin (32.70 ± 17.17 ng/mL vs 28.79 ± 11.83 ng/mL, p = 0.02) all declined. The PIO was well tolerated, with only one adverse event: lower-extremity edema in a patient with low residual renal function.

♦ Conclusions: Blood triglycerides were not altered after 12 weeks of PIO 15 mg once daily in CAPD patients, but parameters of dysmetabolism were markedly improved, including insulin resistance, inflammation, and adipokine balance, suggesting that PIO could be of value for this high-risk patient group. Larger, more definitive studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Pioglitazone, lipid dysmetabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation, adipocytokines

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major cause of mortality in chronic kidney disease patients, including those on peritoneal dialysis (PD). Although survival has not been shown to differ between PD and hemodialysis (1,2), glucose uptake from the dialysate makes PD patients more prone to dyslipidemia, insulin resistance (IR), and obesity (3). These metabolic disorders are substantially linked to the development of CVD and mortality in this patient population (4,5).

Hypertriglyceridemia, reported to be present in 70% of PD patients (6,7), is linked both to glucose uptake from the peritoneum and to IR (8), and is associated with vascular disease (9). Inflammation promotes atherosclerosis and inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein (CRP) that are associated with increased mortality (5). Adipocytokines—such as adiponectin, leptin, and resistin—also play important roles in the development of dyslipidemia, IR, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and CVD in PD patients. Therapies targeting these metabolic disorders should therefore be an important component of treatment for PD patients. Fibrates, acting as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α agonists, can lower serum triglycerides (TGs); however, their limited efficacy and adverse effects (such as rhabdomyolysis and hepatic impairment) hamper their use in PD patients. The PPARγ agonists thiazolidinediones (TZDs), such as pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, exert their hypoglycemic properties through reduction of IR. For more than 10 years, they have been used to control blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The TZDs have also been noted to have beneficial effects on lipid metabolism and inflammation apart from their effects on glycogenic control (10,11). However, data on whether TZDs have a role in the treatment of metabolic disorders in PD patients, especially those without diabetes, are so far lacking (12). We therefore set out to investigate the effect of one of the TZDs, pioglitazone, on hyperlipidemia, IR, inflammation, and adipokine dysmetabolism in continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) patients, especially those without diabetes.

METHODS

PATIENTS

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee on Human Studies at Huashan Hospital of Fudan University, China. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

The study enrolled 36 CAPD patients [>20 years of age, diabetic or nondiabetic, with glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 10%] who had never received TZDs and who had high serum TGs (>1.8 mmol/L). Most of the patients had experienced side effects from fibrates. All patients had received more than 1 month of regular CAPD treatment, involving exchanges of 2 L PD solution (Baxter Healthcare, Guangzhou, China) 2 - 5 times daily. The dialysis prescriptions were kept constant during the study period. Patients who had experienced peritonitis in preceding 3 months or who had heart failure, active neoplasia, unstable CVD, or impaired liver function were excluded from the study. All patients continued their regular medications, such as antihypertensives, erythropoietin, and phosphate binders. Cholesterol-lowering agents (statins), which had been prescribed according to serum cholesterol before enrollment, were kept constant during the study period. No other lipid-lowing agents were prescribed to the patients during the study period.

DESIGN

The study was designed as a prospective randomized crossover trial. The patients were randomly allocated to one of two groups. Group A received oral pioglitazone (Actos: Takeda, Tianjin, China) 15 mg once daily for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks. Conversely, group B received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received pioglitazone for 12 weeks. Food intake was recorded in a continuous self-completed 3-day food diary every 6 weeks. All patients were under the direction of a dietitian and were instructed to eat a low-lipid diet and to take more exercise.

Investigations were performed every 6 weeks: at baseline and at weeks 6, 12, 16 (after the washout period), 22, and 28. Patients arrived at the clinic between 0800 h and 0900 h, after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours. Before the first daily dialysate dwell, fasting blood samples were drawn for serum TGs, cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin, HbA1c, CRP, leptin, adiponectin, and resistin.

The homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) was used to assess IR:

|

The preceding overnight dwells, which had been prescribed before enrollment (2 L of 1.5% or 2.5% glucose solution), were kept constant for the patients during the study period.

Weight was measured after the peritoneal cavity had been emptied. Anthropometry, including body mass index (BMI), abdominal circumference, and triceps skinfold thickness, was also measured. Edema was assessed at each investigation. Cardiovascular events were recorded during the entire study period.

The primary endpoint was change in serum TGs. Secondary endpoints included changes in serum cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, HDL, HOMA-IR, adipocytokines, and CRP.

ASSAYS

Lipid profiles were analyzed using enzymatic methods (Hitachi 7600-020: Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan). Insulin was measured by chemiluminescence assay (ADVIA Centaur XP: Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, New York, NY, USA). Nephelometry (BN II: Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) was used to measure CRP. Adiponectin, leptin, and resistin were measured using ELISA (ABC ELISA kits: R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Other measurements were performed using standard clinical laboratory methods.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All variables were checked for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test for goodness of fit. Variables that did not show normal distribution were log-transformed for subsequent analysis. Changes from baseline were then inserted into a general linear model. To assess for a carryover effect, the sequence of the treatment periods was also taken into account. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the SPSS for Windows software package (version 11.5: SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

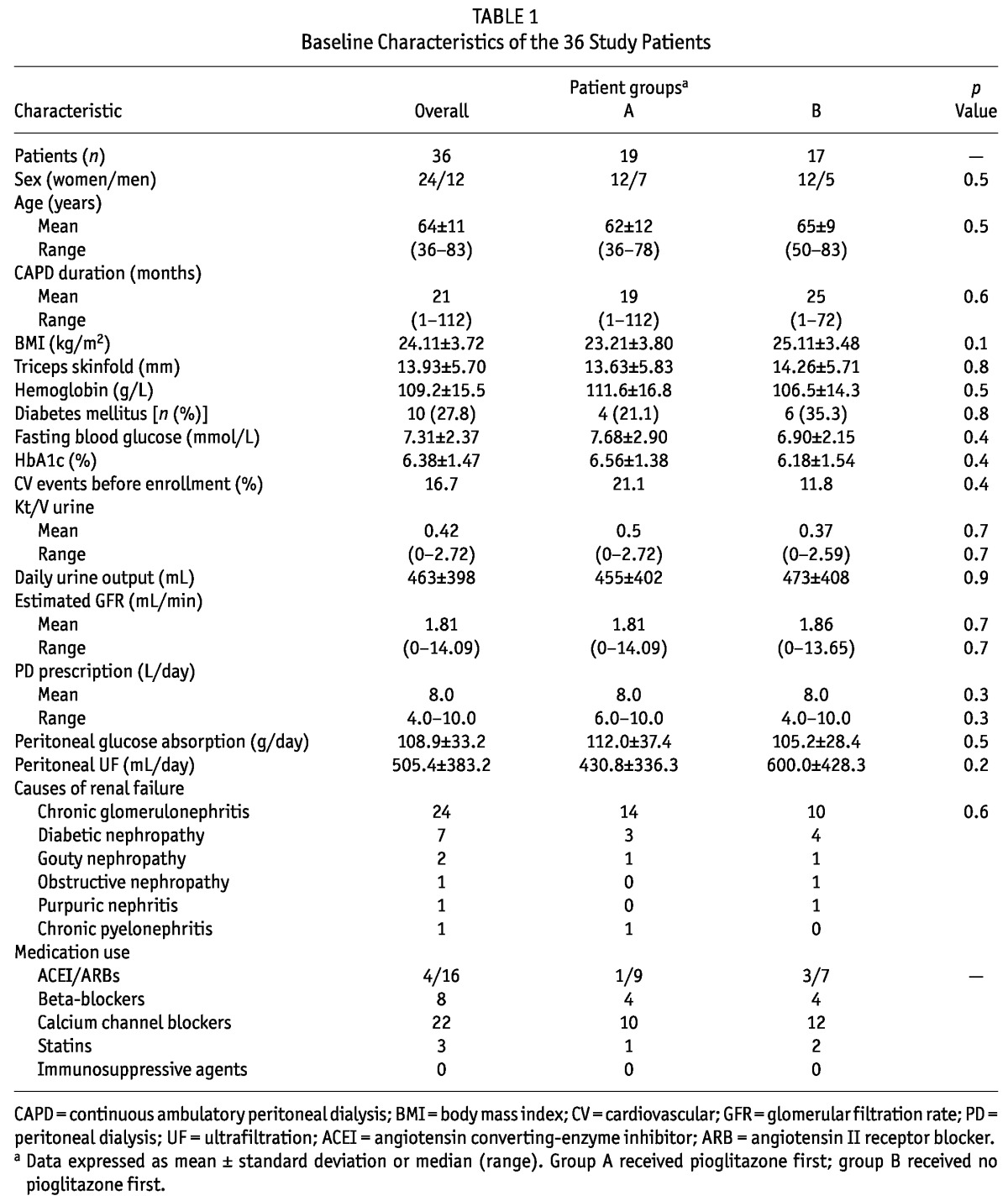

All 36 patients completed the study. Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics of the cohort, including age, sex, duration of CAPD treatment, causes of renal failure, residual renal function, hemoglobin levels, medications, and so on. Patients had an average BMI of 24.11 ± 3.72 kg/m2. Of the 36 patients, 10 had T2DM (7 with diabetic nephropathy, 3 with new-onset diabetes after PD), and all showed reasonable glycemic control (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the 36 Study Patients

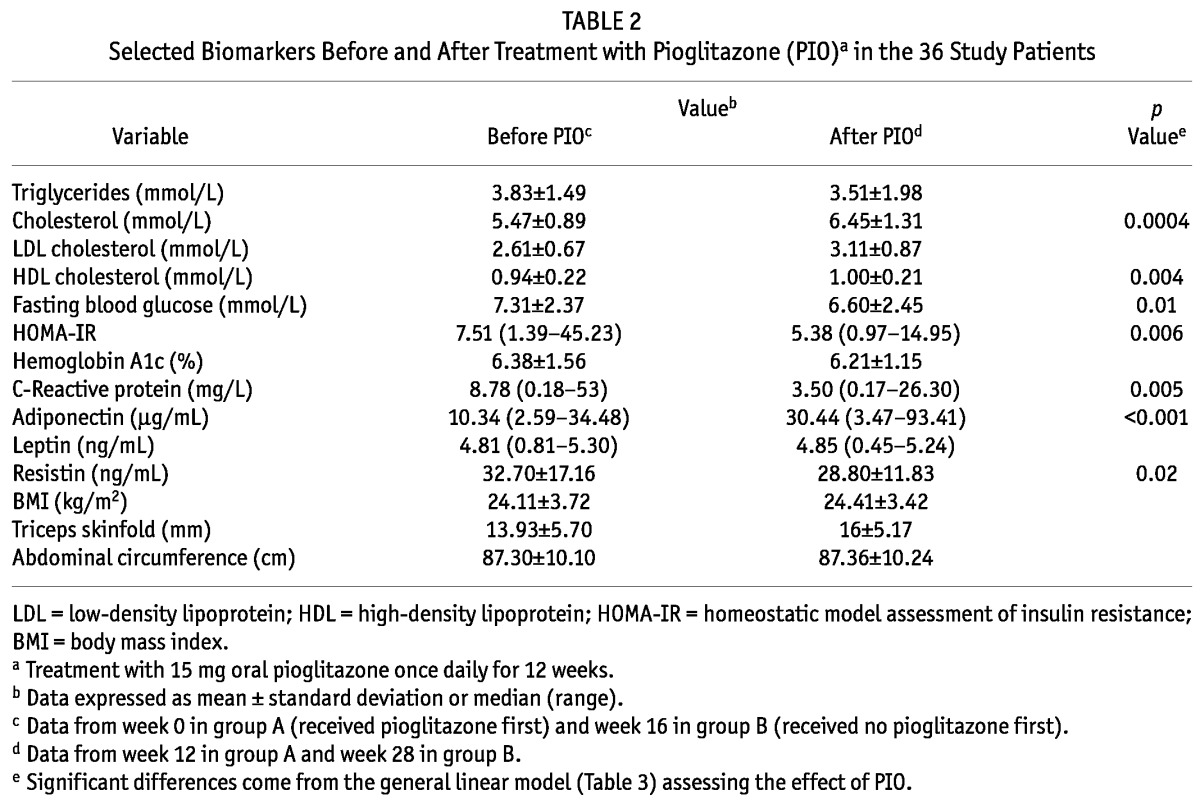

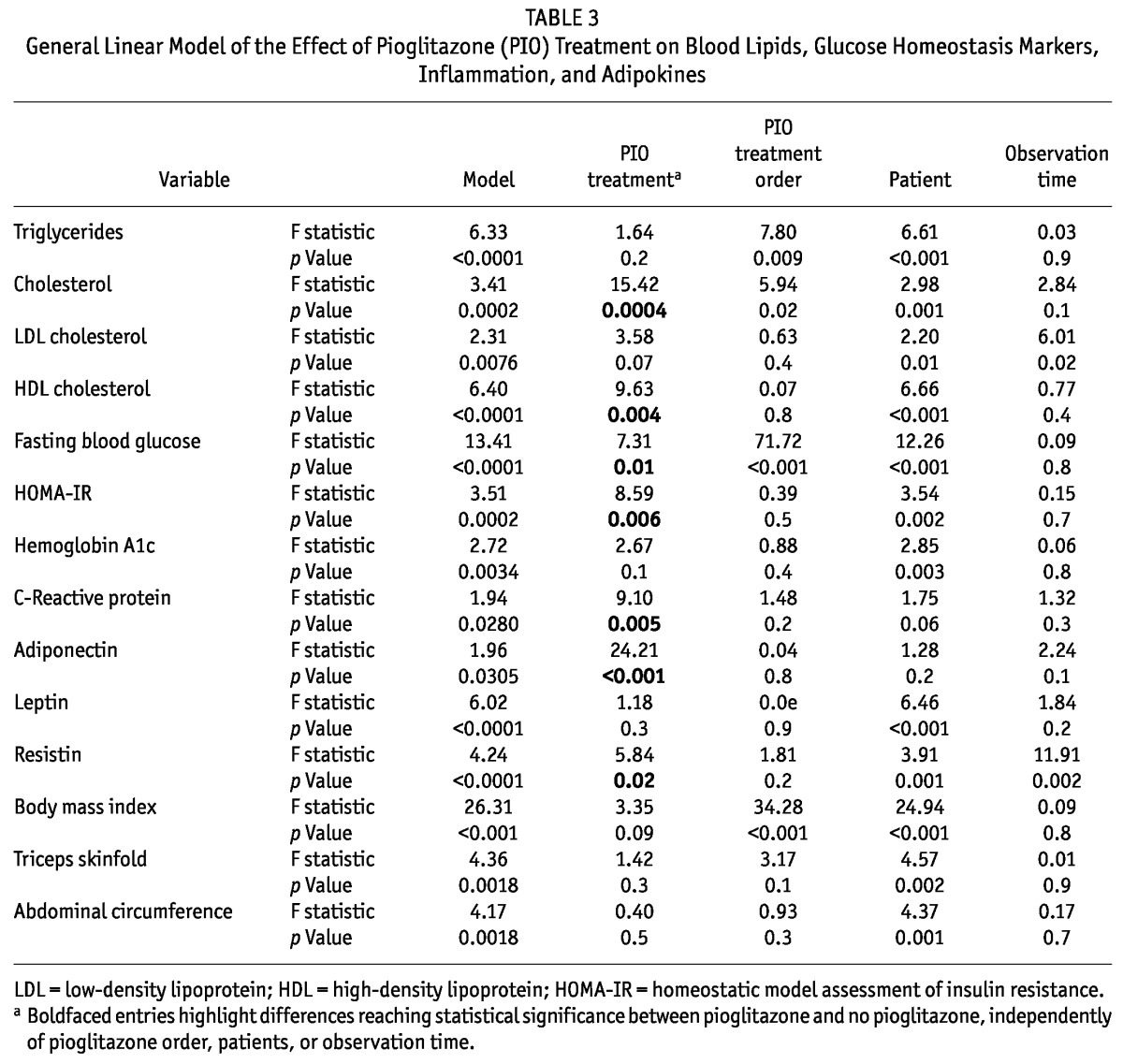

EFFECT OF PIOGLITAZONE TREATMENT ON LIPID PROFILE AFTER 12 WEEKS

Tables 2, 3, and 4 summarize the effects of pioglitazone on lipid profile. Although 12 weeks of pioglitazone therapy resulted in no significant differences of serum TGs (3.83 ± 1.49 mmol/L vs 3.51 ± 1.98 mmol/L, p = 0.2) or low-density lipoprotein (2.61 ± 0.67 mmol/L vs 3.11 ± 0.87 mmol/L, p = 0.07), HDL (0.94 ± 0.22 mmol/L vs 1.00 ± 0.21 mmol/L, p = 0.004) and cholesterol (5.47 ± 0.89 mmol/L vs 6.45 ± 1.31 mmol/L, p = 0.0004) both increased significantly after pioglitazone therapy.

TABLE 2.

Selected Biomarkers Before and After Treatment with Pioglitazone (PIO)a in the 36 Study Patients

TABLE 3.

General Linear Model of the Effect of Pioglitazone (PIO) Treatment on Blood Lipids, Glucose Homeostasis Markers, Inflammation, and Adipokines

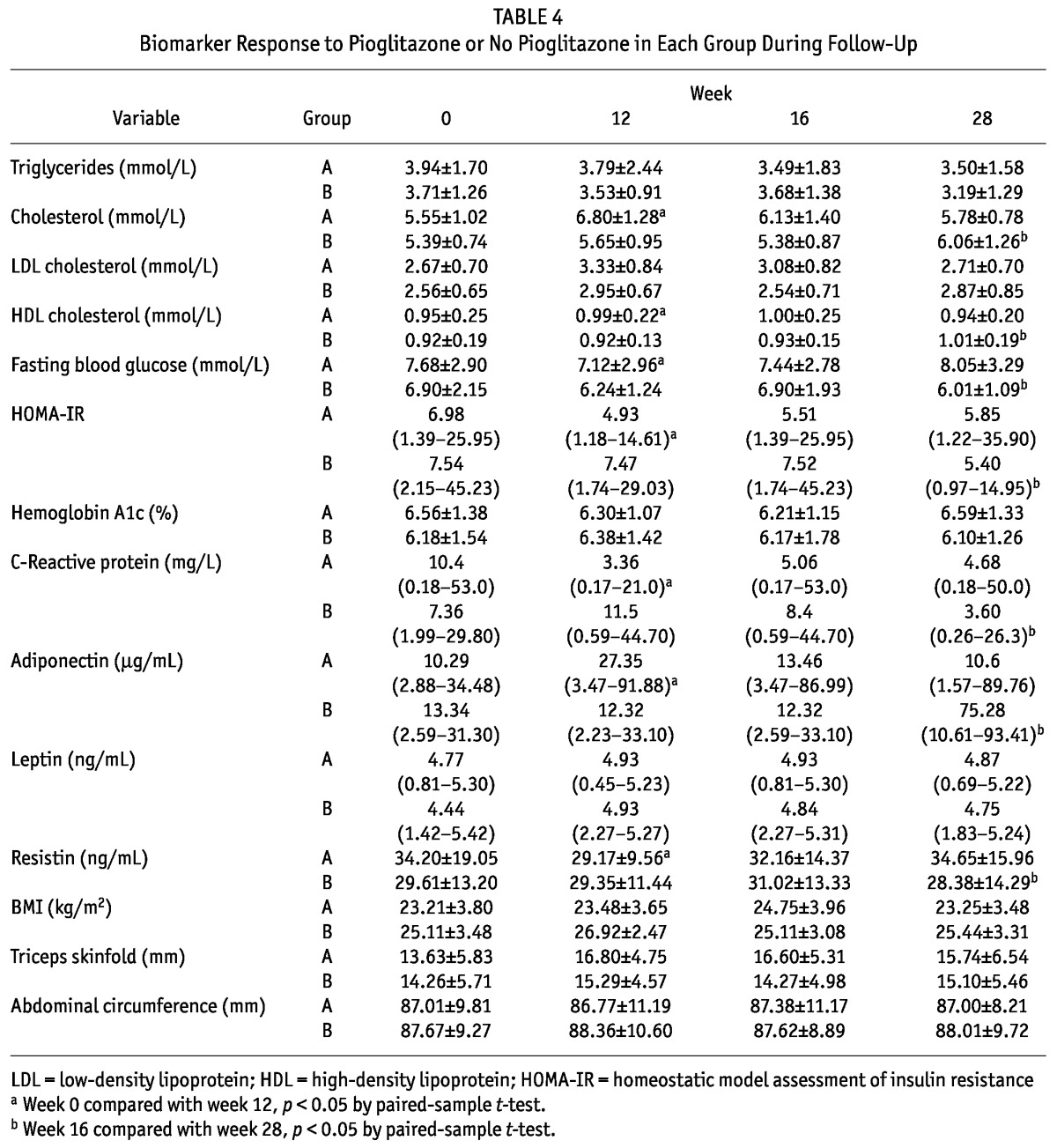

TABLE 4.

Biomarker Response to Pioglitazone or No Pioglitazone in Each Group During Follow-Up

EFFECT OF PIOGLITAZONE TREATMENT ON GLUCOSE CONTROL, IR, AND CRP AFTER 12 WEEKS

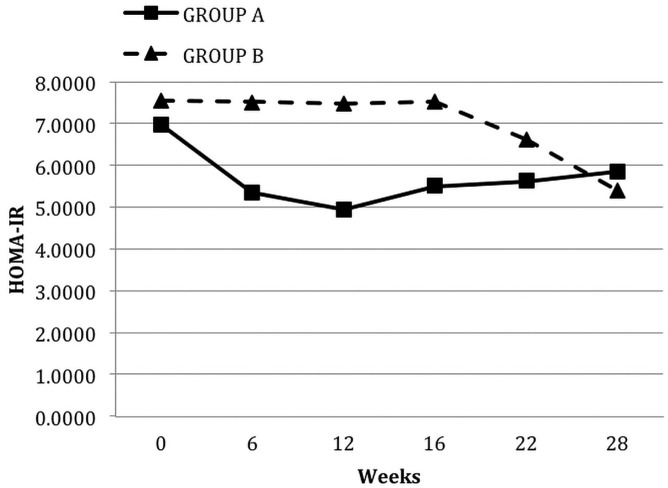

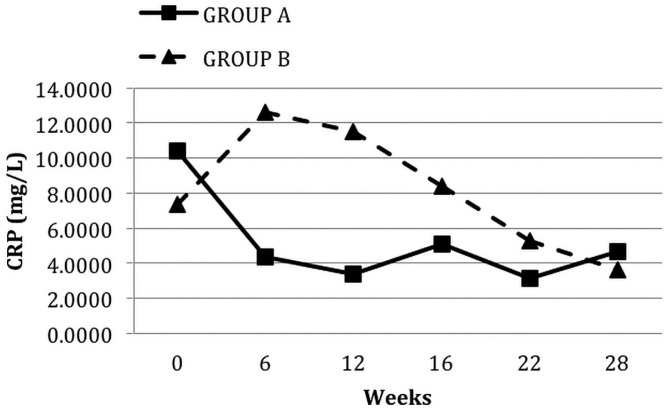

At 12 weeks of pioglitazone therapy (compared with baseline), median HOMA-IR [7.51 (1.39 - 45.23) vs 5.38 (0.97 - 14.95), p = 0.006, Figure 1] and mean fasting blood glucose (7.31 ± 2.37 mmol/L vs 6.60 ± 2.45 mmol/L, p = 0.01) both declined significantly, but no significant change in HbA1c occurred. Pioglitazone significantly reduced median CRP to 3.50 mg/L (0.17 - 26.30 mg/L) from 8.78 mg/L (0.18 - 53 mg/L), p = 0.005, Figure 2.

Figure 1.

— Median levels of homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in the groups during each phase of the study. Group A received oral pioglitazone 15 mg once daily for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks. Conversely, group B received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received pioglitazone for 12 weeks.

Figure 2.

— Median levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the groups during each phase of the study. Group A received oral pioglitazone 15 mg once daily for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks. Conversely, group B received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received pioglitazone for 12 weeks.

EFFECT OF PIOGLITAZONE TREATMENT ON ADIPOKINES AFTER 12 WEEKS

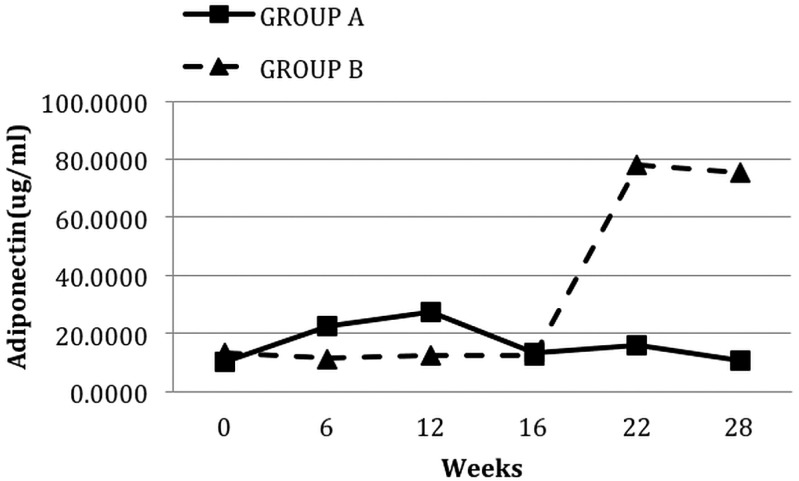

After 12 weeks of pioglitazone treatment, median adiponectin levels increased significantly [10.34 μg/mL (2.59 - 34.48 μg/mL) vs 30.44 μg/mL (3.47 - 93.41 μg/mL); p < 0.001; Figure 3] and mean resistin levels decreased significantly (32.70 ± 17.16 ng/mL vs 28.80 ± 11.83 ng/mL; p = 0.02). However, pioglitazone therapy did not have any significant impact on leptin levels.

Figure 3.

— Median levels of adiponectin in the groups during each phase of the study. Group A received oral pioglitazone 15 mg once daily for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks. Conversely, group B received no pioglitazone for 12 weeks, and then after a washout period of 4 weeks, they received pioglitazone for 12 weeks.

EFFECT OF PIOGLITAZONE TREATMENT ON ANTHROPOMETRY PARAMETERS AFTER 12 WEEKS

We observed no significant changes in BMI, triceps skinfold thickness, or abdominal circumference after 12 weeks of pioglitazone treatment.

SAFETY OF PIOGLITAZONE TREATMENT AFTER 12 WEEKS

During the study, no diabetic or nondiabetic patient experienced a hypoglycemia episode. Fasting glucose in nondiabetic patients did not significantly decrease after 12 weeks of therapy (6.47 ± 1.58 mmol/L vs 6.24 ± 1.58 mmol/L, p = 0.07), although insulin sensitivity increased. None of the patients complained of heart failure symptoms. Also, no cardiovascular events occurred during the entire study period. One patient with significant residual renal function developed lower-extremity edema. With furosemide treatment and restriction of fluid and sodium intake, that symptom quickly disappeared. No patient showed elevation of any liver function test above the normal range.

DISCUSSION

Conventional PD solutions are glucose-based, leading to a carbohydrate caloric load and weight gain in many PD patients. The resulting glucose absorption may worsen the hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, IR, and inflammation that are normally associated with the uremic milieu. Moreover, new-onset hyperglycemia has been described in uremic patients after the start of PD. It is therefore important to find means to attenuate the complex metabolic disturbances in glucose and lipid metabolism seen in PD patients so as to favorably affect clinical outcomes.

The TZDs represent a novel class of compounds for the treatment of T2DM. They are believed to increase the expression and translocation to the cell surface of the glucose transporters Glut1 and Glut4, thus increasing glucose uptake and reducing serum glucose levels (13). The TZDs are also found to be active in lipid metabolism, anti-inflammation, and other metabolic processes in T2DM patients (14). Thus, they could be of value for the treatment of metabolic disturbances in PD patients. However, only a few studies have so far suggested that rosiglitazone might reduce insulin requirements in diabetic PD patients and improve glucose metabolism in nondiabetic PD patients (12,15). To the best of our knowledge, no clinical study has evaluated pioglitazone for the treatment of metabolic disturbance, inflammation, and adipokine dysmetabolism in PD, especially in nondiabetic patients.

The present study demonstrated that 12 weeks of pioglitazone 15 mg once daily did not alter serum TGs in prevalent CAPD patients; however it did increase HDL, improve IR, decrease inflammation, and improve adipokine balance.

In a number of studies, pioglitazone was demonstrated to decrease TG concentrations in nonuremic T2DM patients (16-18). The effect on TG may be related to a partial agonist action of pioglitazone on PPARα receptors. By contrast, pioglitazone therapy did not lower serum TG levels in our study, and we have no clear explanation for this unexpected finding. One possible reason is that the dose of pioglitazone in our study was relatively low. The dose of pioglitazone used in previous studies was 30 - 45 mg once daily in T2DM patients; it our study, it was only 15 mg daily. No prospective study has so far evaluated the dose of pioglitazone for use in nondiabetic PD patients. Given that no hypoglycemia occurred during the entire study period in either the diabetic or nondiabetic patients and that no effect on TGs was observed at the 15-mg once-daily dose, further investigations using a higher dose of pioglitazone are warranted.

In keeping with previous studies in nonuremic T2DM patients, pioglitazone therapy in our PD patients appeared to have beneficial effects on several surrogate markers of CVD risk such as HDL, HOMA-IR, and CRP. The TZDs decrease IR by promoting adipocyte differentiation and the uptake and storage in adipose tissue of free fatty acids. These agents may also restore insulin sensitivity by lowering tumor necrosis factor α (19) and increasing adiponectin expression (20). By suppressing production of interleukin 6 by adipose-tissue macrophages, TZDs could reduce expression of CRP (21).

In the present study, treatment with pioglitazone also had a significant impact on adiponectin and resistin levels. Adiponectin is a unique adipokine with antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-atherogenic effects; it is therefore a possible therapeutic target for the prevention and (eventually) treatment of CVD. A meta-analysis revealed an increase in adiponectin level when patients with diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance, or metabolic syndrome took TZDs (22). That finding accords with the finding in our study that PD patients taking pioglitazone for 12 weeks showed a significant increase in adiponectin levels. We also found that pioglitazone significantly reduced resistin levels; resistin is an adipokine derived not only from adipocytes, but also from peripheral-blood mononuclear cells. Although resistin was discovered during screening for substances that are downregulated in response to insulin-sensitizing antidiabetic drugs, the function of resistin in glucose metabolism in humans is still not clearly understood. Circulating resistin levels are strongly associated with inflammatory biomarkers such as CRP in patients with chronic kidney disease (23). Therefore, acting through resistin, pioglitazone might potentially decrease inflammation in PD patients. Additional long-term studies are required to examine whether these improvements in the surrogate markers of CVD can be translated into a beneficial effect on cardiovascular risk outcome.

The main concern with the use of PPARγ agonists, especially rosiglitazone, in the treatment of T2DM patients is the risk for adverse effects on cardiovascular safety, including the risks of heart failure, myocardial infarction, and stroke (24). Fluid retention may play an important role in the side effects of TZDs on cardiovascular events. Although the underlying mechanisms of TZD-induced fluid retention remain unclear, it is suggested that PPARγ agonists stimulate sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron by upregulating the expression and translocation of the collecting duct epithelial sodium channel. Therefore, spironolactone and amiloride, which interfere with the signaling of PPARγ in the renal distal collecting duct, may be an effective means of reversing TZD-induced fluid retention (25). Compared with rosiglitazone, pioglitazone seems to be safer in treating T2DM patients (26). During our study period, none of the patients experienced a cardiovascular event. Also, no significant changes of weight or BMI occurred after 12 weeks of treatment. One nondiabetic patient with significant residual renal function developed lower-extremity edema; however, volume overload is not uncommon in dialysis patients because of excessive fluid intake. Furthermore, after restriction of fluid and sodium intake and with the use furosemide alone, our patient’s symptoms quickly disappeared. Thus, it can reasonably be inferred that the fluid retention in our patient was not necessarily attributable to pioglitazone use.

Overall, our observations suggest that the combination of the beneficial effects of pioglitazone on TGs and other lipids and certain yet-to-be-defined factors could contribute to the apparent safety of pioglitazone.

The limitations of our study must be acknowledged. First, because of the limited size of our PD center, the study was performed in a small number of patients. To take statistical efficiency into account, we therefore performed a crossover study, which requires fewer subjects than do non-crossover designs. The observation that pioglitazone therapy did not lower serum TGs might be a result of the relatively low dose of pioglitazone used by our patients. However, we observed a lingering effect of pioglitazone on two markers (HOMA-IR and CRP) that carried over into weeks 22 and 28. Larger randomized and non-crossover studies with extensive follow-up are therefore warranted to assess a post-pioglitazone effect. Second, because glucose absorption from dialysate was inconsistent, a more definitive study with a dry night is needed for an exact assessment of HOMA-IR. Third, data on urine output and sodium excretion should also be considered in future investigations to explore whether chronic pioglitazone treatment is associated with worsening of salt and water retention in PD patients.

CONCLUSIONS

After 12 weeks of pioglitazone treatment (15 mg once daily), serum triglycerides were not altered in prevalent CAPD patients, but a surrogate marker of IR (HOMA-IR) and surrogate markers of inflammation declined, and adipokine balance improved. Those results suggest that pioglitazone could be a beneficial therapy for this patient group. However, additional prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to determine whether long-term use of pioglitazone can reduce cardiovascular morbidity in PD patients.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Chun-hai Shao, the dietician, for skillful assistance at the outpatient clinic; Dr. Zhi-jie Zhang and Dr. Bo-bin Chen for assistance with statistical analyses; and Dr. Jonas Axelsson and Prof. Bengt Lindholm from Divisions of Renal Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, and Dr. Man-Fai Lam from Nephrology Division, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, for critically reviewing the manuscript. This study was supported by the Baxter Asia Pacific PD College Research Grant (2008, to Dr. Tong-ying Zhu). The collaboration with Dr. Jonas Axelsson, Prof. Bengt Lindholm and Dr. Man-Fai Lam was made possible by an unrestricted travel grant from Baxter China Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vonesh EF, Snyder JJ, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Mortality studies comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: what do they tell us? Kidney Int Suppl 2006; (103):S3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang CC, Cheng KF, Wu HD. Survival analysis: comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in Taiwan. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28(Suppl 3):S15–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fortes PC, de Moraes TP, Mendes JG, Stinghen AE, Ribeiro SC, Pecoits-Filho R. Insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29(Suppl 2):S145–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shen Y, Peake PW, Kelly JJ. Should we quantify insulin resistance in patients with renal disease? Nephrology (Carlton) 2005; 10:599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pecoits-Filho R, Stenvinkel P, Wang AY, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B. Chronic inflammation in peritoneal dialysis: the search for the holy grail? Perit Dial Int 2004; 24:327–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindholm B, Norbeck HE. Serum lipids and lipoproteins during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Acta Med Scand 1986; 220:143–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cocchi R, Viglino G, Cancarini G, Catizone L, Favazza A, Tommasi A, et al. Prevalence of hyperlipidemia in a cohort of CAPD patients. Italian Cooperative Peritoneal Dialysis Study Group (ICPDSG). Miner Electrolyte Metab 1996; 22:22–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng SC, Chu TS, Huang KY, Chen YM, Chang WK, Tsai TJ, et al. Association of hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance in uremic patients undergoing CAPD. Perit Dial Int 2001; 21:282–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valdivielso P, Sánchez-Chaparro MA, Calvo-Bonacho E, Cabrera-Sierra M, Sainz-Gutiérrez JC, Fernández-Labandera C, et al. Association of moderate and severe hypertriglyceridemia with obesity, diabetes mellitus and vascular disease in the Spanish working population: results of the ICARIA study. Atherosclerosis 2009; 207:573–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan GD, Fielding BA, Currie JM, Humphreys SM, Desage M, Frayn KN, et al. The effects of rosiglitazone on fatty acid and triglyceride metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2005; 48:83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarafidis PA, Lasaridis AN, Nilsson PM, Mouslech TF, Hitoglou-Makedou AD, Stafylas PC, et al. The effect of rosiglitazone on novel atherosclerotic risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. An open-label observational study. Metabolism 2005; 54:1236–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin SH, Lin YF, Kuo SW, Hsu YJ, Hung YJ. Rosiglitazone improves glucose metabolism in nondiabetic uremic patients on CAPD. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42:774–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kramer D, Shapiro R, Adler A, Bush E, Rondinone CM. Insulin-sensitizing effect of rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) by regulation of glucose transporters in muscle and fat of Zucker rats. Metabolism 2001; 50:1294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martens FM, Visseren FL, Lemay J, de Koning EJ, Rabelink TJ. Metabolic and additional vascular effects of thiazolidinediones. Drugs 2002; 62:1463–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wong TY, Szeto CC, Chow KM, Leung CB, Lam CW, Li PK. Rosiglitazone reduces insulin requirement and C-reactive protein levels in type 2 diabetic patients receiving peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46:713–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Matsuda M, Glass L, Mahankali S, Ferrannini E, et al. Improved glycemic control and enhanced insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic subjects treated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Care 2001; 24:710–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenblatt S, Miskin B, Glazer NB, Prince MJ, Robertson KE. The impact of pioglitazone on glycemic control and atherogenic dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Coron Artery Dis 2001; 12:413–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldberg RB, Kendall DM, Deeg MA, Buse JB, Zagar AJ, Pinaire JA, et al. A comparison of lipid and glycemic effects of pioglitazone and rosiglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28:1547–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cabrero A, Laguna JC, Vazquez M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and the control of inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2002; 1:243–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maeda N, Takahashi M, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, et al. PPARγ ligands increase expression and plasma concentrations of adiponectin, an adipose-derived protein. Diabetes 2001; 50:2094–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dandona P. Effects of antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic agents on C-reactive protein. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:333–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riera-Guardia N, Rothenbacher D. The effect of thiazolidinediones on adiponectin serum level: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10:367–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Axelsson J, Bergsten A, Qureshi AR, Heimbürger O, Bárány P, Lonnqvist F, et al. Elevated resistin levels in chronic kidney disease are associated with decreased glomerular filtration rate and inflammation, but not with insulin resistance. Kidney Int 2006; 69:596–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalaitzidis RG, Sarafidis PA, Bakris GL. Effects of thiazolidinediones beyond glycaemic control. Curr Pharm Des 2009; 15:529–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karalliedde J, Buckingham R, Starkie M, Lorand D, Stewart M, Viberti G. Effect of various diuretic treatments on rosiglitazone-induced fluid retention. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:3482–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stafylas PC, Sarafidis PA, Lasaridis AN. The controversial effects of thiazolidinediones on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Int J Cardiol 2009; 131:298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]