Summary

Disability is the result of interactions between biological and environmental factors including the physical, economic, and social barriers imposed on an individual by society. In low and middle-income countries, limited attention has been given to the situation of individuals with intellectual disabilities, who remain seriously neglected. Given the lack of resources available to address mental disorders, it is essential to examine the role of socioeconomic and socio-cultural factors in the lives of these individuals. We conducted interviews of key informants and community members in a shantytown community in Lima, Peru, to explore public knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes regarding intellectual disability. Findings indicated that the most important concern for community members was the longstanding issues associated with poverty. There was a profound lack of awareness of intellectual disability among the general population and an absence of social integration for these individuals. However, interviewees also recognized the productive potential of persons with intellectual disabilities provided they received currently inaccessible support services. The results suggest that educational efforts and intervention strategies must be mindful of the challenges of chronic poverty in order to successfully facilitate the social integration of individuals with intellectual disabilities into the community.

Keywords: Disability, Intellectual disability, Poverty, Social integration, Policy

1. Introduction

The social model of disability states that the condition of disability is less the result of an actual physical impairment than the environmental barriers that effectively disable one’s ability to participate in society.1–4 Social participation is not only dependent upon individual functionality but is largely influenced by public attitudes towards disability.5 However, there is limited empirical data available to describe the social experience of disability for individuals with cognitive impairments.

Previous studies of public attitudes towards the social aspect of intellectual disability have focused on the educational and workplace settings, and have provided a mixture of findings, ranging from positive attitudes towards inclusion within these contexts,6–9 to those that reported negative sentiments.10–13 Such variability underscores the need to understand attitudes towards intellectual disability within each unique social, economic, and cultural setting.

One of the main recommendations of the recent World Health Organization report on disability to increase the community participation of individuals with disabilities has been to augment public awareness and understanding of disability.14 Data on public perceptions of intellectual disability remain limited, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where there are significant barriers to service provision, access and funding. In Latin America in particular, there is currently a lack of epidemiological data and an insufficient understanding of the social situation of people with intellectual disability.15

Peru contains a highly heterogeneous population with immense socioeconomic and sociocultural variability. The country was also one of the first to ratify the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognizes the right of all individuals to full and equal participation in society.16 Nongovernmental organizations and autonomous government entities provide vocational training, therapy and advocacy to improve the lives of citizens with disabilities, though accessibility to these services is an issue. Instances of inappropriate institutionalization of intellectually disabled individuals abandoned by their families, and egregious abuse and neglect within these institutions have also previously been documented.17 Such dissonance makes the country an ideal location to study perceptions about this population.

We report the results of a study whose objective was to provide qualitative information concerning public knowledge, perceptions and attitudes of intellectual disability in a low resource setting in Lima, Peru. The results can assist with the development of informed policy and intervention strategies within the challenges of this specific socioeconomic and sociocultural context.

2. Methods

2.1. Study site

The study was conducted in Paraíso Alto and Edén de Manantial, two ‘pueblos jóvenes’, or shantytowns on the hills lining the periphery of the district of Villa Maria del Triunfo, one of the largest districts in Lima. This is a peri-urban district with a population of 360 000, over half of whom are impoverished, and over one fifth of whom live in extreme poverty.18 Fifteen percent of residents are malnourished; 35% live in dwellings without water while nearly a quarter of residents live in housing without electricity.

2.2. Study population

The study included 12 key informants and 10 community members from the district of Villa María del Triunfo; their demographic background is shown in Table 1. The data are of a preliminary study that will later be used to make comparisons between communities of varying socioeconomic levels in Lima. Key informants were selected based on experience working in health care, education, or community leadership. The inclusion criteria for the key informants were their ability to understand interview questions, age greater than 18 years, and a minimum of two years’ experience working within the community. We recruited community members without consideration as to whether the potential participant had a family member with a disability. A convenience sampling method was used in which a recruiter who herself was a resident of the community was instructed to approach inhabitants within adequately dispersed blocks that the principal investigator identified on a map of the community. Sampling was stratified to ensure that three different age groups were represented, between 18 and 29 years, 30 and 54 years, and over 55 years. An equal distribution by gender was also targeted.

Table 1.

Demographics of interview participants

| Characteristic | Frequency, combined | Frequency, community members | Frequency, key informants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Female | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Age | |||

| Range, years | 20–72 | 20–72 | 30–58 |

| Mean, years | 42.9 | 42.5 | 43.25 |

| Age distribution | |||

| 18–29 years | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 30–54 years | 15 | 4 | 11 |

| ≥55 years | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Occupation | |||

| Health care | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Educator | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Homemaker | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Industry worker | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Service worker | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Clergy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

All potential subjects were contacted by the nongovernmental organization PRISMA due to their existing relationship with the community. Each participant was approached by a member of the research team accompanied by a community health worker who lived in the community and worked with the organization. A total of 26 people were approached of whom 22 agreed to be interviewed. Those who declined were unable or unwilling to invest the time necessary for the interview, or declined to sign the informed consent document.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

A semi-structured interview was developed to explore how each participant defined intellectual disability, their experiences with individuals with intellectual disabilities in their community, and their views on the social, economic and educational situation of such individuals. After respondents first described their own understanding of intellectual disability, a standard definition of intellectual disability was verbally provided in a language that was previously confirmed by the community health worker to be locally appropriate before proceeding with the remainder of the interview.

Key informants were asked additional questions concerning how they interacted with individuals with intellectual disability through their particular field of work. Interviews were conducted between February and May 2009. Interviews lasted 30 to 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed in the original language.

Recorded interviews were analyzed with the ATLAS.ti (version 5.0) software (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The grounded theory approach was used in which interviews were initially reviewed to identify possible categories and concepts. Codes were then developed based on these categories, and interview transcripts were subsequently coded from which overall themes were inductively derived and reviewed in collaboration with a second member of the research team.19

3. Results

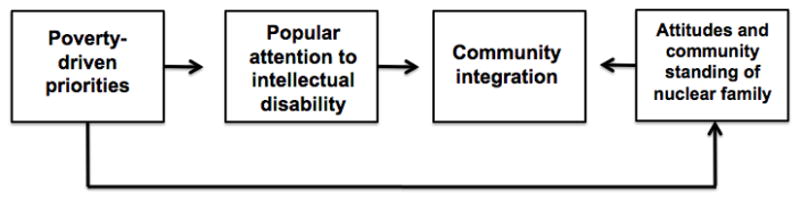

The categories identified from the research are presented with verbatim translations of interview quotes from participants who have described their own understanding of intellectual disability and their perceptions and attitudes towards individuals with intellectual disability in their community. The themes derived from these categories were poverty and its related concerns, lack of attention paid to intellectual disability, and the role of the family. Figure 1 describes the relationship between the factors that were found to influence the community integration of individuals with intellectual disability.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting community integration

3.1. Perceptions of individuals with intellectual disability, and understanding of its causes

Interviewees were asked to give descriptions of people in their community who they believed to have a cognitive impairment. Based on the descriptions of individuals they identified, many interviewees had difficulty differentiating between intellectual disability and other mental disorders. A majority of key informants and community members were able to identify and describe at least two individuals with intellectual disabilities in their community. The ages of those described ranged from 5 to 25 years:

There’s a girl, she is…17 years old… she comes and goes around here… sometimes like a little girl, she sits down and urinates in any place… It seems that her mother sometimes takes her to therapy, but sometimes for economic reasons it seems that no… and here the kids, they know her, and they say, “look, here comes the crazy girl… I’d say poor girl, no? Key informant, woman, 49 years.

I have a friend I work with, his son… he must be 11, 12 years old… there is no treatment… they keep him in the house… he is like a 2 or 3 year old child… for a while they were taking him to the San Juan de Dios clinic… but since they could not do anything, now they just have him in the house. Community member, man, 54 years.

A number of interviewees also reported having no knowledge of any individuals in their communities with intellectual disability, as in the case of this community leader:

There must be [individuals with intellectual disabilities within the community] but the truth is I haven’t seen any. Key informant, man, 37 years.

Participants’ understanding of the causes of intellectual disability included basic scientific background of genetics, disease pathology, physical trauma, or gestational intoxication. Key informants who worked in either education or health care focused more solely on the biological basis of intellectual disability, while community members tended to include a familial basis of causation, including domestic problems, economic insecurity, drug and alcohol abuse, or violence on part of either parent:

It could also be that there are sometimes problems in the home; he goes out drinking, or a lot of things, no? Poverty, bitterness that they don’t have work… Community member, woman, 67 years.

It has many etiologies, there are infectious, hereditary, and genetic causes… the environment, radioactive substances now with this industrial boom minerals, lead poisoning… and on the other hand intrinsic hereditary factors that I mentioned or infectious disease as well… Key informant, man, 42 years.

3.2. Intellectual disability in the context of health care and education

Key informants working in health care reported the highest amount of interaction with individuals with intellectual disabilities, seeing up to two individuals per week in their place of work. They also tended to be the most knowledgeable about the lives of these individuals, and had the most consistent contact with them through work responsibilities. Patient care at hospitals and health posts was not perceived to be of differing quality for patients with intellectual disability. However, the health care professionals generally believed that the number of patients with intellectual disability they saw grossly underrepresented actual community prevalence, as evidenced by the following comment:

Generally for… the patient with severe intellectual disability, I’ve realized that they don’t come, that they’re more in their house, even prostrated… and I speak of adults… and they have them there in bed, at home, no?… it could also be for economic reasons that they don’t come for [health care], or sometimes, they also say, ‘No, Doctor, my son is just like this, he’s going to stay like this, and they’ve told me to keep him at home’ and then… they don’t bring him. Key informant, man, 42 years.

Lack of resources was reported to heavily affect the education of a child with an intellectual disability. If the family wished to send their child away to a special education center (none existed close to the community) they would be required to pay monthly tuition fees. The next viable option would be to send the child to a public school. However, key informants working in education strongly felt that students with intellectual disabilities were better served by special education centers. This was due to what they perceived to be their own inadequate level of training in special and inclusive education:

Even though I can give them a lot of affection here… they don’t advance. At a different site they can give them, I don’t know, materials, things that they can do, no? So they develop. Key informant, woman, 48 years.

There are no schools, our schools, for people with intellectual disability… schools are expensive, no? They are private, and the majority of people do not have access to it. Community member, man, 22 years.

3.3. Intellectual disability and attitudes toward social integration

Attitudes of key informants and community members towards intellectual disability were affected more by personal priorities, ideology, and actual interaction with individuals with intellectual disabilities than by sex or age group. Those who had personally witnessed or interacted with individuals with intellectual disability tended to have stronger views on the importance of social integration.

All but one interviewee believed that individuals with intellectual disabilities had the capacity to perform some kind of labor if provided adequate training. Many reported having observed or heard of individuals with intellectual disabilities working in jobs outside of their own community in Peruvian chain stores. Participants reported a positive reaction by the public to the hiring of these individuals, most of whom were described as having Down syndrome. However, it was also cited that such employees tended to come from families with the economic means to access proper training services:

For example packaging or sticking on price tags… simple things like this that they can do… They carry and hand out packages, [the company] gives them simple work. Other businesses no… they’re afraid they won’t do it well, no? This is the only company that we’ve seen give them a hand… It is the only one I know and it makes me happy, they are noble in this sense. Community member, woman, 72 years.

Both key informants and community members felt that manual labor was the most appropriate form of work for individuals with intellectual disability. It was also cited that these individuals usually do not achieve their full productive potential. Stable job opportunities are scarce in general, and worse for someone with a disability, who will in the calculation of an employer, produce less:

If there is no opportunity for work for the healthy person, it’s less for a person that has an impairment. Key informant, woman, 34 years.

Why would they hire them? Because they maybe have 50% capacity to solve anything. Community member, man, 41 years.

The integration of an individual with an intellectual disability into community life was considered important by all interviewees. Most respondents noted a lack of such integration within their own community. All community members stated that they would respond positively to their own child interacting with a child with an intellectual disability. Many, such as the man quoted below, added that they would caution their children to treat their playmate with greater caution:

…I would tell him, as they’re kids, maybe, to be careful, to treat him like a smaller child that the special child easily gets hurt, and is very sensitive to hits. Community member, man, 21 years.

Key informants referred to a general cultural phenomenon in which individuals are categorized according to personal characteristics or limitations to describe the discriminatory attitudes they reported. Abnormal behavior and learning challenges are no exception, and can be labeled as ‘crazy,’ ‘sick,’ or, in case of distinguishing facial characteristics, ‘mongol.’ People are often nicknamed based on their most striking physical characteristics:

There is much discrimination, we call the fat person ‘gordo’, the short person ‘chato’, we search for adjectives… I include myself because I also live in this country and it’s the first thing that a person with a problem, with a limitation experiences; immediately they classify him… Key informant, man, 38 years.

All participants reported that they would be willing to participate in activities oriented toward the integration of community members with intellectual disability. When asked to provide suggestions for activities to stimulate social integration, key informants suggested informative talks and community-wide advocacy campaigns:

Generally talks, training, go, give information to the people, on how it could be important that everyone integrates themselves as neighbors. Key informant, woman, 49 years.

3.4. Integration and the role of the family

The attitudes of community members towards an individual with an intellectual disability were strongly influenced by the reputation of his or her family. There were cases in which longstanding respect for a family by the community facilitated a positive community attitude towards that individual. For example, it was relatively easier for the community to accept a student with an intellectual disability at the local school whose family was generally respected, and whose sister had previously ranked top in her class:

They treated her well… she was the youngest, calm, they knew… but the respect… I believe, according to my own logic and my perspective, was more for the respect that the family had won. Key informant, man, 38 years.

The community marks that person, mark the person and through it unfortunately [marks] the child. Community member, man, 41 years.

Community integration of individuals with intellectual disability was also strongly influenced by the family’s attitudes, resources and proactive behavior. There were individuals who were allegedly kept shut all day inside their homes, and those who were sent to either a public school or private special education center during the day. Some enjoyed greater levels of interaction with the community and accompanied family members on daily errands such as grocery shopping, or would walk around the neighborhood unaccompanied.

…it depends a lot upon the family, who is taking care of him, and then how this parent integrates him into society… Key informant, woman, 34 years.

They are mostly marginalized by the state, no? And in their family more so… I think they overprotect them… they are not going to want an intellectually disabled person to go then… go alone outside, no? Community member, man, 22 years.

3.5. Poverty and the placement of intellectual disability among existing priorities

Poverty was a prevalent theme in all interviews. The concept of poverty did not positively or negatively influence attitudes per se, but rather drew attention away from the topic of intellectual disability due to its pervasive influence on personal priorities. Such priorities were shared by the entire community, and consisted of stable employment, the need for basic infrastructure and services, and security concerns associated with growing community violence.

For most, the issue of intellectual disability was not taken into consideration prior to the interview due to a constant concern with economic troubles and securing basic necessities. Interviewees tied a significant proportion of their responses to such poverty related concerns:

The area is… let’s say there is a lot of poverty, a lot of need, no? I think the greatest interest is economic. Key informant, woman, 44 years.

Improvement… we need water and sanitation; we are struggling. Community member, woman, 67 years.

It is extremely difficult here in this zone that much attention be given to this topic because in the majority of cases the mother and father have to work, if they are lucky… Key informant, woman, 44 years.

4. Discussion

The present study characterized public perceptions regarding intellectual disability in a peri-urban community of limited resources. Attitudes towards integration did not differ significantly by traditional demographic factors, though other studies have found females to be more accepting of individuals with intellectual disability.20,21 Interviewees who had prior interaction with individuals with intellectual disabilities however tended to strongly favor integration, as has been previously reported.10,21,22 There was no evidence of discriminatory attitudes of interviewees themselves towards intellectual disability. This is in contrast to other studies in low and middle-income countries that have reported a negative association between cultural beliefs and attitudes towards intellectual disability.23,24

The results provide insight into the social dynamics experienced by individuals with intellectual disability as perceived by community members. The education of individuals with intellectual disability was cited to be a challenge, due to a lack of resources within the public school system and the economic inability of families to send their child to a special education center. Following a recent Peruvian law to promote inclusion in the classroom, public schools cannot deny any child admission on the basis of a disability.25 However, key informants in education claimed that teachers lack the training to offer children with intellectual disabilities any substantial education.

One of the largest determinants of integration was cited to be the family’s resources and predisposition to his or her interaction with the community. Such findings are consistent with those recently reported in Mexico, where a combination of insufficient family resources due to economic deprivation and social deprivation resulting from segregation by the family have been cited to lead to the social exclusion of people with intellectual disability. Lack of planning to enforce existing policy to include children with intellectual disability in primary education, and a lack of community-based organizations to offer social support were also described.26

Poverty was a salient theme in all interviews and was the major determinant of attention to the topic of intellectual disability. Poverty-driven priorities are pervasive in the agendas of community members. While much has recently been elucidated about social determinants of health and the role of poverty in its devastating effects on health,27–29 the extent to which the concerns of chronic poverty pose a major obstacle for raising attention to the issue of intellectual disability within the community has yet to be reported.30,31 This finding is of great interest, as public attitudes towards integration are key to increasing access to support services, which first requires a degree of awareness of the issue.5,14

The positive attitudes portrayed by the interviewees may not reflect the reality of attitudes in the community, and this is a limitation of this study. Some respondents may have been unwilling to express negative attitudes towards individuals with intellectual disability. Social desirability bias is a factor that must be considered, as actual negative attitudes may have been underreported. Other limitations include the small sample size and the lack of data sources on the perspectives of stakeholders and affected family members. The study reflects the attitudes of a specific Peruvian community with distinct socioeconomic and sociocultural circumstances, which can be extrapolated to a certain degree to other communities with similar characteristics.

The results of this study suggest that potential avenues for policy and intervention strategies to increase popular attention to the issue of intellectual disability should include educational campaigns to raise popular consciousness about the issue. However, it is clear that any strategy to further increase the social integration of individuals with intellectual disability must also address the issues associated with poverty to achieve greatest impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the Asociación Benéfica PRISMA, the Flinn Foundation, and the Biology Research Abroad: Vistas Open! Program.

Funding: This work was carried out with financial support from the National Institutes of Health (5 T37 MD001427) and the Flinn Foundation. The participation of Dr. Lescano in this project is sponsored by the training grant NIH/FIC 2D43 TW007393 awarded to NAMRU-6 by the Fogarty International Center of the US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

One author of this manuscript is an employee of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of his duties. Title 17 U.S.C. § 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. § 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Authors’ contributions:

MSO worked on development of the research questions, the data collection plan, data analysis, interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. DLT was involved with the research plan, data analysis, interpretation of results and the preparation of the final manuscript. AGL was involved with the research plan and design as well as the preparation of the final manuscript. LC was involved with the research plan and design of the study and the preparation of the final manuscript. JMG was involved with the interpretation of results and the preparation of the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MSO and DLT are guarantors of the paper.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board and the ethics committees of the Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University and the PRISMA non-governmental organization in Peru.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gartner A, Lipsky D, Turnbull A. Supporting families with a disability: an international outlook. Baltimore: Paul Brookes; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogdan R, Biklen D. Perspectives on disabilities. 2. Palo Alto: Health Markets Research; 1993. Handicapism; pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson J. The disabled, the media, and the information age. Westport: Greenwood Press; 1994. Broken images: portrayals of those with disabilities in American media; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes C, Mercer G. Disability. Cambridge: Polity; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rees LM, Spreen O, Harnadek M. Do attitudes towards persons with handicaps really shift over time? Comparison between 1975 and 1988. Ment Retard. 1991;29:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guralnick MJ, Connor RT, Hammond M. Parent perspectives of peer relationships and friendships in integrated and specialized programs. Am J Ment Retard. 1995;99:457–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooney G, Jahoda A, Gumley A, Knott F. Young people with intellectual disabilities attending mainstream and segregated schooling: perceived stigma, social comparison and future aspirations. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50:432–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy JJ, Rimmerman A, Levy PH. Determinants of attitudes of New York State employers towards the employment of persons with severe handicaps. J Rehabil. 1993;59:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger D. Employers’ attitudes toward persons with disabilities in the workforce: myths or realities? Focus Autism Other Dev Disabil. 2002;17:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siperstein GN, Norris J, Corbin S, Shriver T. Multinational study of attitudes toward individuals with intellectual disabilities. Washington DC: Special Olympics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke K, Sutherland C. Attitudes towards inclusion: knowledge vs. experience. Education. 2004;125:163–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhagat F. Exploring inclusion and challenging policy in mainstream education. Br J Nurs. 2007;16:1358–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith P. Have we made any progress? Including students with intellectual disabilities in regular education classrooms. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2007;45:297–309. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2007)45[297:HWMAPI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercadante M, Evans-Lacko S, Paula C. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Latin American countries: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:469–74. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832eb8c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UN. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillman A, Rosenthal E, Okin R, Ríos M, Peñaherrera L, Yamin A. Human rights and mental disability in Peru. Washington DC: Mental Disability Rights International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.IPES Promoción de Desarrollo Sostenible. Villa Maria planting for life: situation, limitations, potential, and actores of urban agriculture in Villa Maria del Triunfo [in Spanish] Lima: Instituto Para la Economía Social; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gash H, Gonzales SG, Pires M, Rault C. Attitudes toward Down syndrome: a national comparative study: France, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain. Irish J Psychol. 2000;21:203–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pace JE, Shin M, Rasmussen SA. Understanding attitudes toward people with Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2185–92. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maras P, Brown R. Effects of contact on children’s attitudes toward disabilities: a longitudinal study. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1996;26:2113–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwardraj S, Mumtaj K, Prasad JH, Kuruvilla A, Jacob KS. Perceptions about intellectual disability: a qualitative study from Vellore, South India. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:736–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau J, Cheung C. Discriminatory attitudes to people with intellectual disability or mental health difficulty. Int Soc Work. 1999;42:431–44. [Google Scholar]

- 25.General Law of the Person with Disability, Peruvian Law No. 27050, art. IV (1998).

- 26.Katz G, Márquez-Caraveo M, Lazcano-Ponce E. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Mexico: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:432–5. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833ad9b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan G. The effects of poverty on children. Future Child. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hertzman C, Boyce T. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annu Rev of Public Health. 2010;31:329–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social determinants of health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emerson E, Graham H, Hatton C. The measurement of poverty and socioeconomic position in research involving people with intellectual disability. Int Rev Res Ment Retard. 2006;32:77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emerson E, Parish S. Intellectual disability and poverty: introduction to the special section. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2010;35:221–3. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2010.525869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]