Abstract

In October 1998, the National Library of Medicine (NLM) launched a pilot project to learn about the role of public libraries in providing health information to the public and to generate information that would assist NLM and the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM) in learning how best to work with public libraries in the future. Three regional medical libraries (RMLs), eight resource libraries, and forty-one public libraries or library systems from nine states and the District of Columbia were selected for participation. The pilot project included an evaluation component that was carried out in parallel with project implementation. The evaluation ran through September 1999. The results of the evaluation indicated that participating public librarians were enthusiastic about the training and information materials provided as part of the project and that many public libraries used the materials and conducted their own outreach to local communities and groups. Most libraries applied the modest funds to purchase additional Internet-accessible computers and/or upgrade their health-reference materials. However, few of the participating public libraries had health information centers (although health information was perceived as a top-ten or top-five topic of interest to patrons). Also, the project generated only minimal usage of NLM's consumer health database, known as MEDLINEplus, from the premises of the monitored libraries (patron usage from home or office locations was not tracked). The evaluation results suggested a balanced follow-up by NLM and the NN/LM, with a few carefully selected national activities, complemented by a package of targeted activities that, as of January 2000, are being planned, developed, or implemented. The results also highlighted the importance of building an evaluation component into projects like this one from the outset, to assure that objectives were met and that evaluative information was available on a timely basis, as was the case here.

INTRODUCTION

Prior to 1997, health consumers represented a very small percentage of the total population accessing National Library of Medicine (NLM) databases [1]. In June 1997, NLM made two announcements with major implications for consumer usage. First, as of that date NLM made its major databases, including MEDLINE®, available via a Website on the Internet; second, NLM waived all fees for users accessing NLM databases via the Web (previously users were required to have account numbers and pay hourly charges for electronic access). Since that time, the number of MEDLINE searches has exploded from seven million to more than 220 million per year, of which an estimated one-third are members of the public, broadly defined. NLM has intensified its efforts to improve access via the Web and to develop more consumer-friendly databases and has held workshops and conducted research focusing on interface and connectivity problems (e.g., a study by Wood et al. [2]). One of these initiatives involved an exploratory project to better understand the role of public libraries in meeting consumer health information needs and how NLM and the National Network of Libraries of Medicine (NN/LM) might collaborate with public libraries. The focus on public libraries reflected in part the results of other surveys suggesting that public libraries have been increasingly providing Internet access for consumers seeking a variety of information [3–5], presumably including health information.

Planning for the “Public Library Consumer Health Information Pilot Project” (“pilot project” for short) began in spring 1998. Participants were selected from public and medical libraries in three of NLM's eight regions, and each participating public library was paired with a supporting medical library in the NN/LM. Many participants attended a preliminary planning workshop held in July 1998. The workshop served to orient the participants and to obtain early feedback and baseline data from the participating sites. The pilot project formally started on October 22, 1998, which coincided with public release of an early version of MEDLINEplus, an NLM Website that provided links to selected quality sources of health information that were appropriate for consumers. The project was directed by Becky Lyon, head of NLM's National Network Office, and guided by a Steering Committee comprised of Lyon; Eve-Marie Lacroix, chief of NLM's Public Services Division (responsible for developing the MEDLINEplus Website); Fred Wood, D.B.A., of NLM's Office of Health Information Programs Development (responsible for project evaluation); and Kathleen Cravedi of NLM's Office of Communications and Public Liaison (responsible for project publicity and promotion).

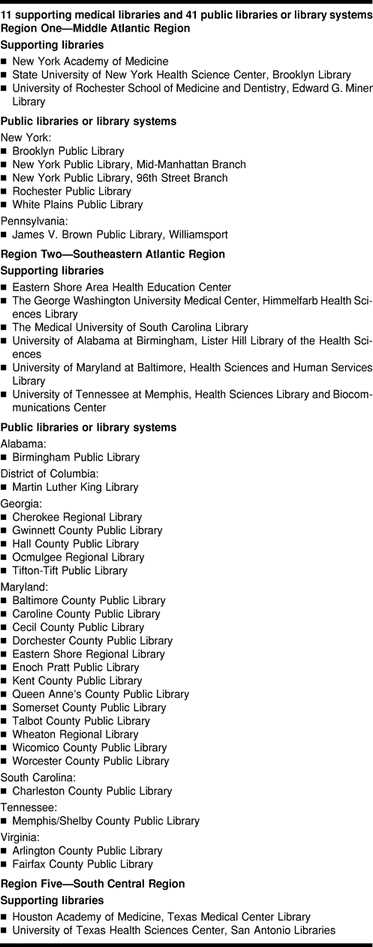

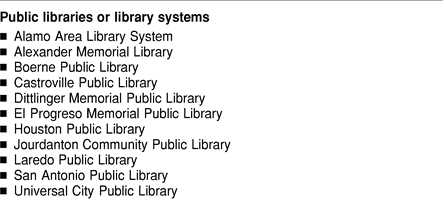

The pilot project objectives were to learn about the role of public libraries in meeting consumer health information needs, obtain feedback from public librarians and patrons about NLM health information services, understand better how NLM and the NN/LM might work with public libraries in the future, and consider the implications of the pilot project for a national program. The pilot project ran for a little more than eight months, through the end of June 1999. The project evaluation ran through September 1999. In all, three RMLs, eight resource libraries (other medical libraries in the NN/LM), and forty-one public libraries or library systems from nine states and the District of Columbia participated in the project (Table 1).

Table 1 Public library pilot project participants

An important component of the pilot project was an evaluation plan that was developed in fall 1998 and implemented in parallel. Indeed, the evaluation component became an integral part of the pilot project itself. The purpose of this article was to report on the results of the pilot-project evaluation as carried out by NLM. The authors believed that the use of evaluation in this context demonstrated the importance of viewing project evaluation as part of project planning and, then to the extent possible, building the evaluation component into a project from the outset. During the past decade, outreach to user populations has been one of NLM's highest priorities. Yet, effectively evaluating outreach has also been one of the toughest challenges. A five-year review, carried out in the mid-1990s, of literally hundreds of outreach projects had among its recommendations that “NLM and the RMLs should work together to develop further expertise in evaluation methodology … [and that] … evaluation components should be an integral part of all NLM-sponsored research” [6]. The pilot project was an opportunity for NLM to implement this recommendation.

METHODS

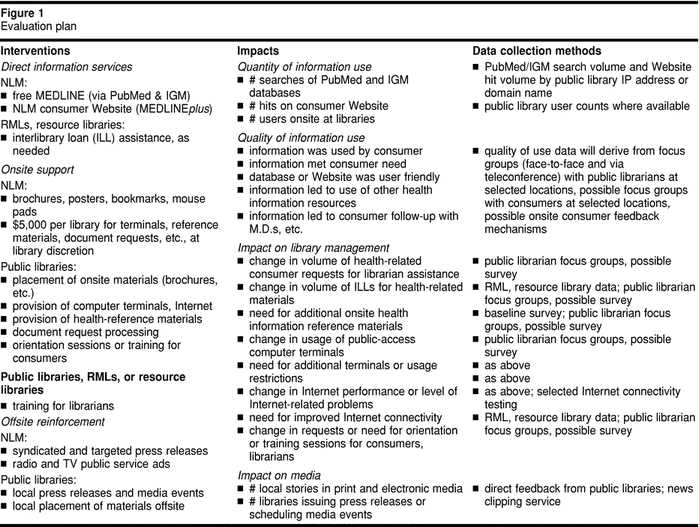

A complete evaluation framework (Figure 1) was developed at the outset of the pilot project. The framework provided a way to conceptualize the entire evaluation process and integrate a number of discrete evaluation techniques into a coherent whole. The framework, in the lefthand column, listed the range of interventions planned as part of the pilot project, including direct information services provided by NLM and the RMLs and resource libraries (e.g., MEDLINE and MEDLINEplus on the Web, interlibrary loan support); onsite support at the public libraries provided by NLM, public libraries, and/or RMLs and resource libraries (e.g., placing promotional materials, training); and offsite reinforcement provided by NLM and public libraries (e.g., syndicated press release, local press release, local outreach). The framework included the types of impacts to be monitored as part of the evaluation, originally conceptualized in terms of the quantity and quality of health-information use by consumers at the participating libraries, and impact of this use on library management and the media. The framework listed the data collection methods planned for each of the identified impact areas.

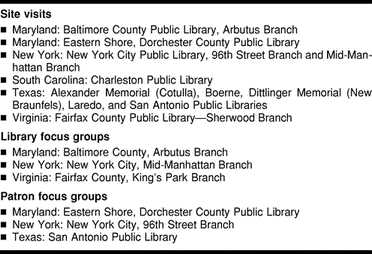

This framework was used throughout the project, in order to manage and guide the evaluation activities. The main components of the evaluation methodology included regular feedback from participating librarians (using monthly teleconferences and written reports), site visits to selected libraries (Table 2), librarian and patron focus groups (Table 2), individual closeout telephone interviews with all participating libraries, and monitoring of NLM database usage from participating libraries (using IP addresses). The monthly librarian teleconferences, closeout interviews, site visits, and librarian focus groups proved to be particularly effective and helpful. Patron focus groups were difficult to arrange, although the few held did produce some useful results.

Table 2 Public library site visits and focus groups

A background information survey was completed at the outset of the project by all participating public library sites. This survey covered basic factual information about the then-current status of onsite health-reference materials, Internet-accessible computers, and use of health information on the Web. In lieu of a closeout survey at the end of the pilot project, the lead librarian at all participating sites was interviewed in depth by telephone. Also, the use of consumer feedback sheets as originally contemplated did not prove feasible overall and, in the few attempted instances, produced very limited results.

The usage monitoring encountered significant technical and methodological difficulties. The objective of this monitoring was to measure the usage of NLM databases (specifically, PubMed, Internet Grateful Med, and MEDLINEplus) from the participating public libraries. This monitoring was to be accomplished by tracking usage from the Internet addresses of computers located at the participating sites. The original list of Internet addresses submitted from the participating libraries was far too large to be feasibly monitored. The list was shortened by consolidating multiple IP addresses into network IP addresses and by the use of domain names where possible. However, errors in both the original IP addresses supplied by the libraries and some of the original domain names were discovered later in the project. Significant effort was required to verify and correct the Internet addresses used. Also, sites with dynamic IP addresses (due to dial-up Internet access) could not be monitored. After all corrections were made, NLM was able to successfully monitor usage from thirty of the public libraries or systems (representing a total of 161 physical library sites, including branch libraries).

RESULTS

The data and information collected from each evaluation activity were integrated and analyzed within the overall evaluation framework. The results are organized and presented by major topic or impact area.

Role of health information at public libraries

Most of the participating public libraries did not have a health information center and had not previously focused on health information. As a consequence, many librarians were not yet comfortable with providing health reference assistance to patrons, in part because of concerns about providing misinformation and possibly intruding on patron privacy. Librarians appreciated the opportunity to learn more about health information and generally welcomed an information source such as MEDLINEplus that provided some measure of quality control.

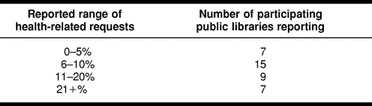

Health information was generally considered one of the top-five or top-ten topics of interest to patrons. About two-thirds of the libraries estimated that health requests account for 6% to 20% of their total reference requests (Table 3). Libraries that had specialized science and technology departments and that kept separate statistics by department had higher percentages of health-related requests, ranging up to 60%. Also, some librarians noted that even when the number of health-related reference requests was low, the amount of time spent per health request tended to be among the most time-intensive type of request. This was because the answer to a health query typically might not be a simple fact or single reference, but might involve more complex exploration of several resources that in turn may require some explanation. A countervailing trend mentioned by some librarians was the tendency of patrons to go right to the Internet-accessible computers and bypass the reference desk.

Table 3 Estimated health-related reference requests as a percentage of total requests

Role of computers and reference materials

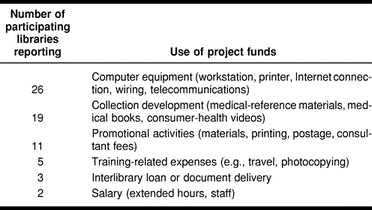

About two-thirds of the participating libraries used some or all of their $5,000 grants to purchase computer equipment or upgrade Internet connections (Table 4). Almost half used some funds to purchase medical-reference materials. Many libraries split their funds on both equipment and materials. About one-fourth of the libraries used some funds for promotional activities and lesser percentages (under 10%) for training, interlibrary loans, or staffing.

Table 4 Participating public library use of project funds

Smaller libraries tended to emphasize equipment and reference materials. Accordingly, the greatest relative impact was reported to be on the smaller libraries, where the addition of one or two computers or upgrading reference materials could make a big difference. This impact was demonstrated at the Alexander Memorial Library in Cotulla, Texas (a small-town, rural library serving a largely Hispanic community located about midway between San Antonio and Laredo). Here, the NLM-grant funds were used to double the number of Internet-accessible computers (from one to two) and substantially increase and update the health reference collection. These enhancements directly benefited the local school children who use the library after school for Internet access and class projects, senior citizens who visit the library during the day, and working parents who come by in the late afternoons and evenings.

The larger library systems tended to give relatively higher priority to developing promotional materials, organizing outreach, and setting up document delivery services and other activities that would benefit all branches. For the group of participating libraries as a whole, upgrading computers and related equipment was the top priority, with remaining funds used for collection development and promotional materials. Demand for Internet-accessible computer time exceeded supply in many public libraries.

Public librarians and training

Participating librarians were enthusiastic about the training they received as part of the pilot project. An estimated 1,150 public library staff members and volunteers attended one or more group training sessions held by regional and resource libraries. For some, this session was their first training in health information and first opportunity to visit a health sciences library. Training sessions were usually at least one half-day long at the assigned supporting library. Participants were provided with training packets and other information to take back to their libraries and were encouraged to train their colleagues at the local library or system. The train-the-trainer approach seemed to work well.

In contrast to librarian training, patron training varied widely and, for the most part, was one-on-one. Many public libraries were not equipped or staffed to hold patron workshops or regular classes. A total of thirty-one participating libraries or systems reported one-on-one training by a library staff member (the actual number may have been higher, because some libraries did not define one-on-one encounters as training per se). Six participating libraries offered one-time patron workshops, with reported attendance of five to twenty persons. Four libraries held regular classes, with reported attendance averaging three to ten persons. While most libraries had a conference room that could be used for training, few libraries had a room reserved solely for training and fewer still a computer training facility.

Promotional materials and activities

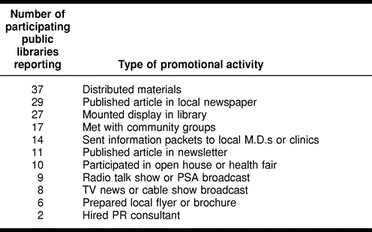

The public librarians responded very positively to the promotional materials provided by NLM and NN/LM. In total, NLM and the NN/LM distributed an estimated 13,300 brochures, 9,280 bookmarks, 792 posters, 715 pens, and 300 mousepads, with an additional 4,905 Spanish-language brochures and 3,700 Spanish-language bookmarks.

Almost all participating libraries reported distributing such materials to patrons, but many initiated or participated in various other promotional activities (Table 5). About two-thirds of the libraries published an article or announcement in the local newspaper and mounted some kind of display in the library. Roughly a third reported presenting information to community groups and sending information packets to local physicians or clinics. About a quarter published an article in a newsletter and attended or sponsored an open house or health fair. Roughly one-fifth reported receiving local media coverage, mostly in the smaller cities and rural towns.

Table 5 Participating public library promotional activities

In general, the libraries with smaller staffs had greater difficulty promoting the project, beyond the distribution of materials and setting up displays onsite. However, the more rural or small town libraries had better luck in getting local newspaper and media coverage, given the relative lack of competitive news. Newspaper and media coverage was hard to come by in the large urban markets. The larger library systems usually had more staffing (or even a public relations department) with which to coordinate elaborate media events, visits by dignitaries, and community participation.

However, few librarians were able to assess the impact of any of these promotional activities, other than the occasional anecdote (primarily regarding patrons who mentioned a news story or media coverage). Direct patron feedback on promotional activities likewise was very limited.

Most participating librarians were not experienced in or interested in arranging patron focus groups or other mechanisms for obtaining user feedback. Some librarians expressed concerns about patron privacy. Two libraries provided patrons with feedback sheets, but responses were too few to be useful. NLM conducted focus groups at three libraries, with a total of twenty-five patrons (some were health professionals). These groups did provide useful insights into health information–seeking behavior and frequently used sources of health information, as well as direct feedback about MEDLINEplus and suggestions for improvement.

Outreach

About one-half of the participating libraries conducted some form of outreach or combination of outreach and promotion targeted to some community of current or potential users of health information. Some of the more interesting outreach activities included:

demonstrations, presentations, and classes for specific groups of health-information users and potential users (e.g., school nurses, health clinic staff, disease-specific patient support groups, senior centers, employee groups, local hospitals, church-based health centers);

participation via displays, brochures, and demonstrations at local health fairs, senior citizen expositions, and bookmobile activities;

cosponsorship of blood pressure tests and other health-screening and health-promotion activities and events at the local library; and

presentations about the pilot project and health-information sources at meetings of library administrators, friends of the library, community leaders, and local government councils and departments.

Overall, librarians perceived that outreach activities generated a more noticeable and direct response than most promotional activities. Librarians reported observing, for example, nursing students, patient support group members, and physicians coming into the library following a presentation or other outreach activity. The most successful outreach programs reportedly were those devoted to a specific disease or condition. Those libraries that offered both general health–information and disease-specific workshops found that the disease-specific approach generated greater interest and participation.

MEDLINEplus

The feedback from librarians about MEDLINEplus was quite positive, as was the limited feedback from patrons. Enthusiasm seemed to grow as more health topics, additional links, and improved functionality were added to MEDLINEplus during the course of the pilot project. Most of the feedback provided during the pilot project was reflected in eventual revisions and improvements made to MEDLINEplus.

However, NLM's monitoring of MEDLINEplus usage indicated that, in the aggregate, usage from the participating libraries grew very little over the course of the project. Usage did increase significantly during the early spring of 1999 (late March–early April), apparently due to intensified librarian and patron training sessions, but eased back down after that to a level of about 3.5 hypertext markup language (HTML) page downloads on average per week per library site at the end of the pilot project. This average translated into about one to two usages per week per library, assuming that each user session generated at least two to three page downloads on the average. In comparison, these library sites generated on average about three to four PubMed searches per week and less than one Internet Grateful Med search per week.

The MEDLINEplus usage from all participating libraries combined (the 161 library sites actually monitored) accounted for about 400 page downloads per week during the last month of the pilot project (June 1999). Through September 1999 (the end of the evaluation period), usage from the monitored libraries was essentially flat. One caveat was that the monitoring did not capture any usage of library patrons after they returned to their homes or offices, only usage from computers on library premises.

In contrast, overall MEDLINEplus usage increased modestly during the last few months of the project. Thus, the monitored public library usage as a percentage of total MEDLINEplus usage declined from a peak of about 1% in March 1999 to about 0.5% in June 1999 and declined further as overall MEDLINEplus use continued to increase. MEDLINEplus use rose about 30% from June through September 1999 (and subsequently began to grow exponentially—by an order of magnitude by January 2000).

In order to interpret the usage data fully, the data were normalized to determine the usage per location. The total number of hits during an eleven-month period (October 22, 1998–September 18, 1999) ranged, for example, from more than 4,000 hits (HTML page downloads) for the Baltimore County Public Library system to fewer than 100 hits for the Martin Luther King Library in the District of Columbia. The Baltimore County, Charleston County, Fairfax County, and Houston public library systems were among those recording the largest number of hits. But when adjusted for the number of branch libraries in these systems, the number of average hits per branch location was actually less than for some of the individual public libraries. The largest number of hits per week per location varied from about twenty-six hits at the main branch of the Memphis/Shelby County Public Library, to about twenty hits at the two participating branches of the New York City Public Library (Mid-Manhattan and 96th Street), and to eighteen hits at the Wicomico County Public Library (Eastern Shore, MD) and at the Rochester, New York, Public Library. Some libraries in fairly small towns had comparatively high usage levels, such as Wicomico County and the public libraries in Boerne, New Braunfels (Dittlinger Memorial), and Laredo, Texas. The latter three libraries averaged about six to seven hits per week, several times the overall average for all libraries.

In general, individual libraries had much higher usage per location than library systems with multiple branches. This usage appeared to reflect in part the relative diffusion of resources and effort in large library systems with many branches. Other factors at play included the level of librarian interest at each location, the degree of management support, the experience with health information, and the demographic variables such as population and education.

Reference and interlibrary loan requests

Most participating public libraries reported no noticeable increase in health reference, interlibrary loan (ILL), or document requests during the course of the project. RMLs and resource libraries likewise observed no noticeable increase in ILL or document requests, with a very few exceptions that were related to specific individuals, not an overall trend. These observations were consistent with the low level of monitored MEDLINEplus usage from participating libraries. Public librarians seemed to agree that ILL or document requests would be unlikely to increase significantly even with much higher MEDLINEplus usage, because, in their view, most patrons wanted to leave the library with materials in hand and to make do with what was on the Internet or the shelves.

Many of the supporting libraries expressed a concern, at the outset of the pilot project, that they might be swamped with document delivery requests originating from public library patrons. This concern proved to be unfounded. Five of the eleven supporting libraries were not asked to supply any articles; two libraries supplied fewer than ten articles; and two libraries supplied about fifty articles during the course of the project. Only two libraries supplied more than 100 documents, and this apparently did not present a problem. The New York Academy of Medicine reported that it supplied a total of 142 articles, still considered an insignificant percentage of its total document-delivery activity.

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of the pilot project is to help NLM decide how to best work with public libraries to promote consumer access to health information. The pilot project appears to have succeeded in this regard. NLM has concluded that it and the NN/LM can assist public libraries with becoming better sources of health information for the public. The pilot project also has confirmed that NLM and the NN/LM will need to work with a variety of organizations and groups—not just public libraries—to understand the public's health information needs and to improve public access to health information. NLM and the NN/LM should continue to focus some resources on reaching the public via public libraries because: (1) public libraries are available to members of the public who may lack other sources; and (2) public libraries can provide training, support, and resource materials to those who do have computers and Internet connections at home.

A limiting factor is that public libraries in general are not organized around health information as a top priority, in part because these libraries have to meet a broad spectrum of public-information needs and cannot excessively emphasize one topic area at the expense of others. Another limiting factor is that many patrons may obtain health information directly from the Internet, at home or at work, or from health care providers or other sources, rather than or in addition to the local public library.

On the other hand, there is a clear perception among public librarians participating in the pilot project that health is a top-ten topic area and that a significant (but not precisely known) percentage of patrons seek health information at the library. Also, the feedback from librarians and patrons, while limited, suggests that MEDLINEplus is well suited to help meet consumer needs. MEDLINEplus is perceived as being competitive with other Internet-based consumer health information resources. Some public libraries, especially smaller, more rural, or less economically advantaged libraries, seem to benefit significantly even from modest resources for enhanced health-reference materials or Internet-accessible computer terminals. Most of the public libraries seem to appreciate and use onsite promotional materials, especially the bookmarks and brochures. Also, almost all seem to appreciate training for librarians about health information (including NLM databases) on the Internet.

The evaluation results suggested the following items for consideration as part of NLM's future role regarding public libraries. All of these items were in various stages of development or implementation as of January 2000:

offer health information training for public librarians, with coverage of NLM databases and other Internet resources, by RMLs and resource libraries on a regional, rotating basis as part of consumer health information outreach (being implemented);

provide a Web-based “train-the-trainer” course for public librarians that in turn could be used by public libraries to offer a “consumer-oriented medical reference course” as part of their own patron training (being developed);

provide selected promotional materials (e.g., brochures and bookmarks) through the NN/LM distribution networks in limited volume to interested public libraries (being developed);

provide Web-based, self-training modules and traditional “hard copy” instructional brochures for consumer use of NLM databases (being developed);

fund formal evaluations of selected public library health information outreach or connection projects, with the goal of better understanding the complex of factors that affect public access to health information via public libraries and the efficacy of various interventions (being planned)—these evaluations could utilize the NLM-sponsored field manual on outreach planning and evaluation [7];

sponsor or cosponsor public library and consumer user surveys, focus groups, and Web-usage monitoring and analysis, to gain a deeper, more complete understanding of the health information needs, uses, and access points of the general public (being planned);

sponsor usability studies to directly gauge and measure public reaction to and interaction with NLM databases (being implemented);

participate in library association conferences, activities, and newsletters that are highly leveraged in reaching public librarians (being implemented);

provide a Website to distribute information about NLM products and services updates to public libraries and to share training and outreach ideas (being planned); and

-

target limited financial resources for Internet-accessible computer terminals or health-reference materials for public libraries with special needs (being implemented, as part of consumer health information special projects);

– emphasize public libraries in underserved, minority, rural, or economically disadvantaged areas, where a clear and present need exists that is not being met by other federal, state, or corporate philanthropic programs;

– emphasize partnerships between public libraries and physicians, hospitals, health clinics, and other health providers, educators, and intermediaries in the local community—as part of public library connections or consumer health information outreach projects.

In January 2000, NN/LM subcontracts were awarded to forty-nine institutions in thirty-four states to develop partnerships between NN/LM libraries and groups to improve health information services to the public [8]. Many of these projects will involve public libraries, as well as public health departments, schools, churches, community-based organizations, physicians' groups and other health care providers, educators, and intermediaries. A variety of different approaches will be tested and evaluated.

NLM maintains an enduring interest in and places great value on evaluation as a tool to enable important management decisions and to assess the quality and impact of its programs and services. The NLM commitment to evaluation dates back at least to the early 1980s and has continued through each successive generation of technology, from online card catalogs [9], to CD-ROM [10], to MEDLINE [11], to telemedicine [12], and now to the Internet [13]. The experience with the public library pilot project has demonstrated that a proper evaluation methodology, if viewed as an integral part of a project plan, can be successfully implemented in a way that both complements project execution and contributes to sound management decision making. In this case, the project evaluation results have helped define NLM's future directions in working with public libraries as part of the partnerships through which NLM and the NN/LM are striving to improve consumer access to Internet-based health information available from NLM and elsewhere.

Table 1 Continued

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Donald A. B. Lindberg, M.D., NLM director; Tenley E. Albright, M.D., former chair of the NLM Board of Regents; and Betsy L. Humphreys, NLM associate director for Library Operations. And we appreciate the assistance of other NLM staff who participated in the pilot project implementation or evaluation: Eve-Marie Lacroix, Nancy Roderer, Kathleen Cravedi, Joyce Backus, Naomi Miller, Dennis Benson, Lawrence Kingsland, Ph.D., Angela Ruffin, Colette Hochstein, Robin Moore, and Nancy Bladen. We also thank the medical and public librarians from the three RMLs, eight resource libraries, and forty-one public libraries or systems (Table 1) who were vital to the success of both the project and its evaluation. And we thank Beryl Glitz of UCLA and Catherine Burroughs of the University of Washington for leading focus groups. The pilot project benefited from grant support from the Kellogg Foundation to the Friends of the NLM, which defrayed some of the cost of public outreach materials.

The contributions of Mary Beth Schell and Paula Kitendaugh were supported in part through their appointments to the NLM Associate Fellowship Program, sponsored by NLM and administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education. For their second-year fellowships, Schell is affiliated with the Health Sciences Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Kitendaugh is affiliated with the Health Sciences Library, Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

This article is based in part on a presentation by Dr. Wood at the September 28, 1999, NLM Board of Regents meeting.

REFERENCES

- Wood FB, Wallingford KT, and Siegel ER. Transitioning to the Internet: results of a National Library of Medicine user survey. Bull Med Lib Assoc. 1997 Oct. 85(4):331–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood FB, Cid VH, and Siegel ER. Evaluating Internet end-to-end performance: overview of test methodology and results. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998 Nov–Dec. 5(6):528–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertot JC, McClure CR. American Library Association Office for Information Technology Policy: the 1998 national survey of U.S. public library outlet Internet connectivity: summary results. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Chandler K. National Center for Education Statistics: use of public library services by households in the United States: 1996. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Public libraries in the United States: 1993. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford KT, Ruffin AB, Ginter KA, Spann ML, Johnson FE, Dutcher GA, Mehnert R, Nash DL, Bridgers JW, Lyon BJ, Siegel ER, and Roderer NK. Outreach activities of the National Library of Medicine: a five-year review. Bull Med Lib Assoc. 1996 Apr. 84(2 supp):1–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs C, Fuller S, Wood FB, and Siegel ER. Guide to planning, evaluating, and improving health information outreach: 2000. Seattle, WA, and Bethesda, MD: University of Washington and NLM, in press. [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine announces initiative to help public use online health information. [Web document]. Bethesda, MD: The National Library of Medicine. [14 Jan 2000]. 〈http://www.nlm.nih.gov/news/press_releases/ehip.html〉. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel ER, Kameen K, Sinn SK, and Weise FO. A comparative evaluation of the technical performance and user acceptance of two prototype online catalog systems. Info Tech Lib. 1984 Mar. 3(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp BA, Siegel ER, Woodsmall RM, and Lyon-Hartsmann B. Evaluating MEDLINE on CD-ROM: an overview of field tests in library and clinical settings. Online Rev. 1990 Jun. 14(3):172–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg DAB, Siegel ER, Rapp BA, Wallingford KT, and Wilson SR. Use of MEDLINE by physicians for clinical problem solving. J Amer Med Assoc. 1993 Jun 22–30. 269(24):3124–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ. Telemedicine: a guide to assessing telecommunications in health care: 1996. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Library of Medicine announces initiative to help public use online health information. [Web document]. Bethesda, MD: The National Library of Medicine. [14 Jan 2000]. 〈http://www.nlm.nih.gov/news/press_releases/ehip.html〉. [Google Scholar]