Abstract

Two nitroimidazole modified thymidines 1a and 1b have been synthesized and incorporated into DNA oligomers. The 350 nm photolysis of 1a and 1b generated a 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical that induced DNA interstrand cross-links (ICL). Higher ICL yield was observed under hypoxic conditions than aerobic conditions. The photoproducts of monomers or DNA oligomers were isolated and characterized by NMR and/or mass spectroscopy.

Keywords: nucleosides, DNA damage, hypoxia-selective, DNA cross-linking, UV-photolysis

DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) are deleterious to cells because of their unyielding obstruction to replication and transcription.[1, 2] For example, a single unrepaired ICL can be sufficient to kill an eukaryotic cell. Many anticancer agents, such as mitomycin C, nitrogen mustard, and chlorambucil, can kill cancer cells by alkylating DNA opposing strands. However, these agents are also toxic to healthy cells. One approach to reduce the toxicity of the cross-linking agents for normal cells is to trigger site-selective crosslink formation in tumor cells. Hypoxia appears to be a common and unique property of cells in solid tumors, and is an important potential mechanism for the tumor-specific activation of prodrugs.[3–5] Therefore, it is of great interest to develop agents that can form DNA ICLs selectively under hypoxic conditions.

Exogenous molecules have been developed that sensitize DNA to γ-radiolysis under anoxic conditions, such as nitroimidazole and nitrophenyl derivatives.[6, 7] Coupling of a nitroaryl group with active species resulted in hypoxia-targeting anticancer drugs.[8] The non-native nucleosides 5-bromo- and 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine are also used as radiosensitizers.[9] Recently, Greenberg’s group has reported that a phenyl selenide-modified thymidine (dT-SePh) produced DNA interstrand cross-links (ICLs) upon UV-photolysis or γ-radiolysis via a nucleotide radical.[10–13] The ICL formation is independent from oxygen.[10, 12a] We expect that the introduction of a hypoxic radiosensitizer to the modified nucleosides will make them more sensitive to photolysis under hypoxic condition. All these encourage us to synthesize two nitroimidazole-modified pyrimidine nucleosides (1a, 1b), and determine their radiosensitivity and hypoxia selectivity in respect to DNA ICL formation. Our investigations showed that 1a and 1b can form ICL selectively under hypoxic condition.

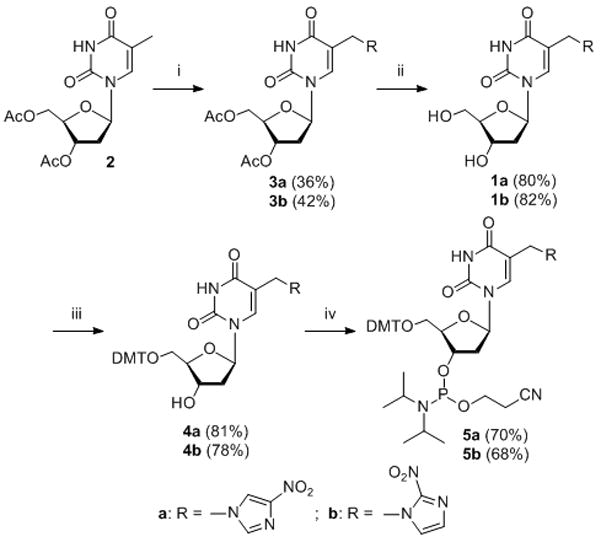

Compounds 1a and 1b were synthesized starting from thymidine (dT), which was protected in the sugar moiety with an acetyl group (2) (Scheme 1). The bromination of 2 followed by the introduction of nitroimidazole group resulted in 3a and 3b. Deprotection of 3a and 3b yielded 1a and 1b, which were converted to their phosphoramidite building blocks 5a and 5b. Oligonucleotides (6–13) containing 1a or 1b were synthesized via automated solid-phase synthesis using 5a or 5b. The coupling yields were more than 98%.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compound 1a and 1b. Reagents: i. a) NBS, benzene, b) NaH, nitroimidazole, DMF; ii) aq. NH3, 1, 4-dioxane; iii) DMTCl, pyridine; iv) 2-cyanoethyl-N, N-diisopropyl-chlorophosphoramidite, N, N-diisopropylethylamine, CH2Cl2.

The nitroimidazole slightly decreased the duplex stability (6 and 10) with a ΔTm of 3–4 °C relative to when dT was present (duplex 14) (Table 1). Similar to dT, 1a and 1b show mismatch discrimination towards dC (ΔTm = −10.8 and −8 °C), dG (−7.7 and −5.7 °C), and dT (−10.4 and −8.6 °C). These data suggest that 1a and 1b form a Watson-Crick base pair with dA.

Table 1.

Melting temperatures [in °C] of duplexes 5′-dAGATGGATXTAGGTAC (complementary strand 3′-dTCTACCTAYATCCATG).

| X•Y | Tm (ΔTm) | X•Y | Tm (ΔTm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dT•dA (14) | 52.1 | ||

| 1a•dA (6) | 48.8 | 1b•dA (10) | 47.7 |

| 1a•dC | 38.0 (−10.8) | 1b•dC | 39.7 (−8.0) |

| 1a•dG | 41.1 (−7.7) | 1b•dG | 42.0 (−5.7) |

| 1a•dT | 38.4 (−10.4) | 1b•dT | 39.1 (−8.6) |

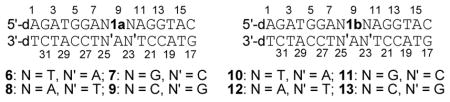

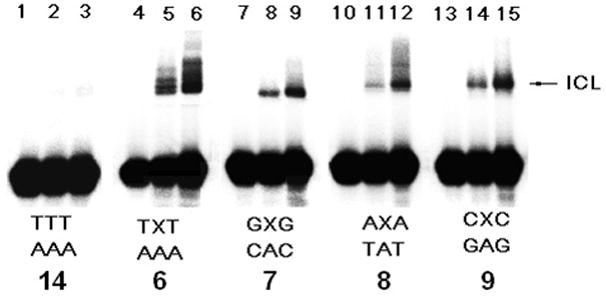

All DNA duplexes were photo-irradiated at 350 nm using a Rayonet Photochemical Chamber Reactor (Model RPR-100). A wavelength of 350 nm was chosen because near-UV light (> 300 nm) is not/slightly absorbed by most biological molecules and is compatible with living cells.[14] Both compounds have absorbance at 350 nm (A = 0.08 for 0.023 mM 1a and A = 0.19 for 0.023 mM 1b) (Supporting Information, SI, Figure S46). Furthermore, the nitroimidazole derivatives can be excited by 350 nm to form a radical anion transition state.[15] The UV-photolysis of 6 resulted in a new band whose migration is severely retarded relative to unreacted oligonucleotide, indicative of interstrand cross-linked material (Figure 1). The cross-linking yield under hypoxic condition (3.6%) is 1.6 times higher than that under aerobic condition (2.2%) (Figure 1, lanes 5 vs. 6). We also examined cross-link formation with duplexes 7–9 in which 1a is flanked by different sequences (Figure 1, lanes 8 vs. 9, 11 vs. 12, 14 vs.15). In all cases, hypoxic conditions resulted in higher cross-linking yield than aerobic conditions (Figure 2A). This further proved the hypoxia-selective cross-linking formation induced by 1a. In a control experiment, an otherwise identical duplex (14) containing dT in place of 1a was irradiated by UV, while less than 0.2% ICL was observed under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. This indicated that the nitroimidazole group in 1a plays an integral role in ICL formation and hypoxia-selectivity in 6–9. In order to determine the generality of this property, we synthesized 2-nitroimidazole modified thymidine (1b), and examined its ability for ICL formation. Similarly, higher cross-linking yield was observed under hypoxic conditions than that under aerobic conditions when the duplexes containing 1b (10–13) were irradiated at 350 nm (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Hypoxia-selective interstrand cross-link formation by 1a upon UV-photolysis at 350 nm for 2 h under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Phosphorimage autoradiogram of 20% denaturing PAGE analysis of the ICL product from duplexes containing 1a (6–9): Lanes 1, 4, 7, 10 and 13, DNA duplexes without UV irradiation; Lanes 2, 5, 8, 11 and 14, DNA duplexes irradiated under aerobic condition; Lanes 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15, DNA duplexes irradiated under anaerobic condition.

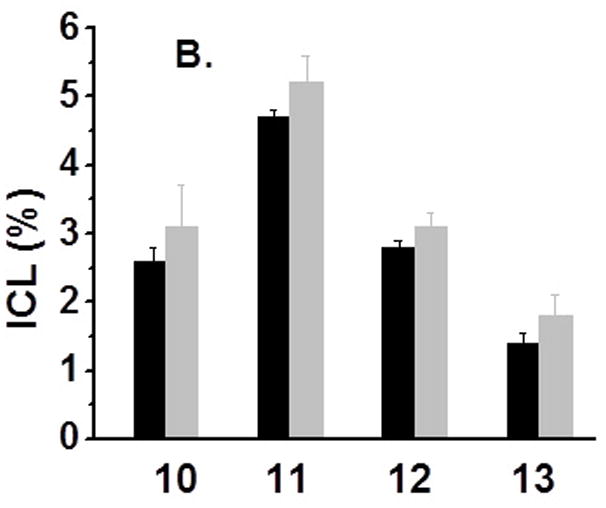

Figure 2.

Cross-linking efficiency of compounds 1a and 1b under aerobic and anaerobic conditions: (A) Duplexes containing 1a (6–9) were irradiated by UV for 2 h; (B) Duplexes containing 1b (10–13) were UV-irradiated for 2 h [black bar -aerobic conditions (air); grey bar - anaerobic conditions (Ar2)].

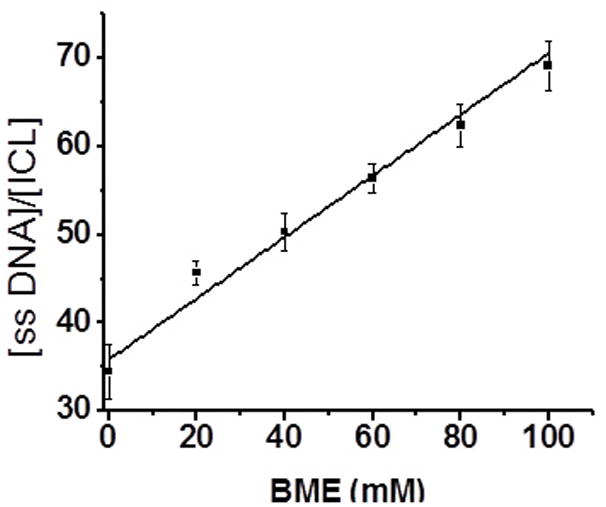

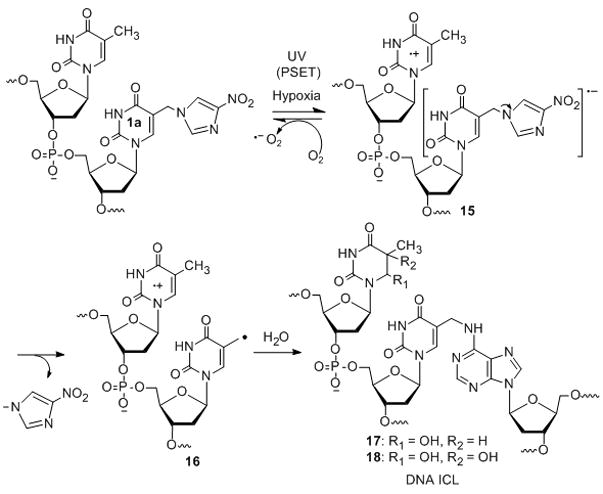

There are two possible mechanisms for the ICL formation, either through a 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical 16 [12] or via formation of a carbocation derived from the protonated 1a or 1b.[16] However, the carbocation mechanism is considered particularly unlikely as the incubation of duplexes 6 and 10 at 37 °C in a buffer of pH 5–9 produced no ICL, whereas the incubated reaction mixture afforded the cross-linking adduct after 350 nm photolysis (SI, Figure S2). The support for the radical mechanism was obtained by determining the rate constant for ICL formation in 6 by measuring the dependence of its formation on the concentration of thiol (RSH, β-mercaptoethanol). [12, 13] The estimated rate constant (kICL) for ICL formation induced by 1a was 3.5 ± 0.3 × 104 s−1 when the upper limit for alkyl radical trapping by a thiol (KRSH = 1 × 107 M−1 s−1) is used (eq 1) (Figure 3). [12] This is consistent with the rate constant for ICL formation from 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical 16 (kICL = 3.8 × 104 s−1) that was observed by Greenberg et al. [12]

Figure 3.

Ratio of ssDNA:ICL produced from 6 as a function of BME concentration (ssDNA: single stranded DNA; ICL: interstrand cross-links).

| (1) |

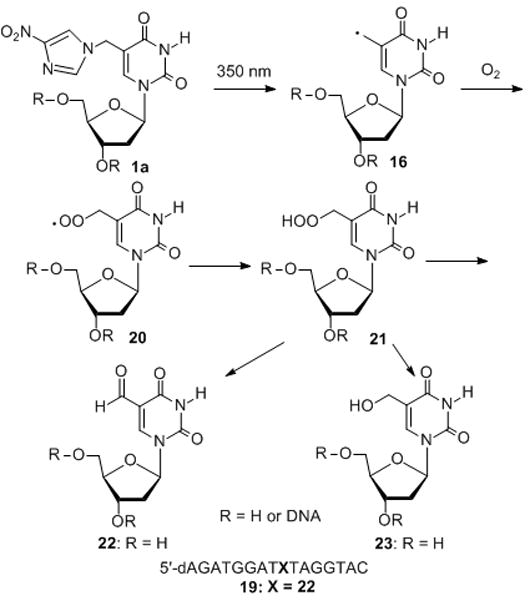

The formation of nucleotide radical 16 was further proved by the analysis of the product formed by 350 nm photolysis of the monomer. When 1a was irradiated for 3h under aerobic conditions, 5-hydroxymethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (23) was observed. Compound 23 was confirmed using an authentic sample (SI, Figure S45). The formation of a hydroxymethyl derivative from 16 was also reported by Greenberg and Cadet.[12, 17] All these indicated that 350 nm photolysis of 1a released nitroimidazole, and generated 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical 16 which finally produced ICL formation. The details and mechanism for the ICL formation by 16 has been reported by Greenberg et al.[11, 12] The final ICL product induced by 1a and 1b is stable to heating in phosphate buffer, which is consistent with the previous report (SI, Figure S1, lanes 3 and 6).[11, 12] However, the cleavage bands were observed upon piperidine treatment (SI, Figure S1, lanes 2 and 5). This indicated that apart from the cross-linking reaction, other side reactions took place.

While the reason for the hypoxia selective ICL formation is unclear, an attractive mechanism appears to the formation of a radical anion 15 via a photo-induced single electron transfer (PSET) from dT8 or other nucleotides in the duplex DNA to 1a or 1b.[18] The resulting anion would spontaneously release nitroimidazole anion to generate 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl) methyl radical 16 which directly produces ICLs (17 and 18). Oxygen molecules can reoxidize the one-electron reduced radical anion 15 to the original agent 1a or 1b, thereby decreasing the ICL yield. This was further proved by the slower rate of disappearance of monomers upon 350 nm photolysis in the presence of air (K1a-air = 4.9 × 10−6 s−1; K1b-air = 1.7 × 10−4 s−1) than that in the presence argon (K1a-Ar = 6.1 × 10−6 s−1; K1b-Ar = 2.4 × 10−4 s−1). In addition to the ICL formation, direct strand breaks (DSB) (2–7%, SI, Figure S1, lanes 1 and 4) and alkaline labile lesions (10–15%, SI, Figure S1, lanes 2 and 5) were observed specially at the positions of the flanking dT8 and the modified nucleosides 1a,b. We believe that 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl)methyl radical in 16 would abstract hydrogen of the sugar moiety of the thymidine radical cation producing a direct strand break at dT8. Greenberg et al. has shown that nucleotide radical can abstract C-2′ hydrogen from the 5′-adjacent nucleotide.[18] In addition, the thymidine radical cation in 16 can react with water to form alkaline labile lesions such as thymine glycol and/or 5-hydroxyl-5,6-dihydropyrimidine derivatives (17 and 18) which produce cleavage bands upon piperidine treatment (SI, Figure S3A, C, lane 3 and SI, Figure S4A, C, lane 3).[15, 19, 20]

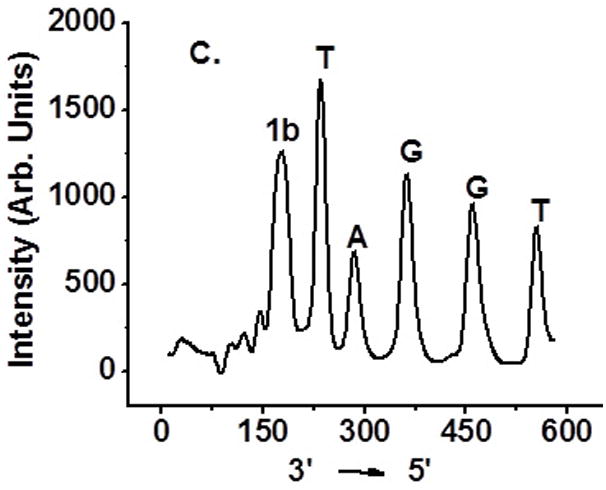

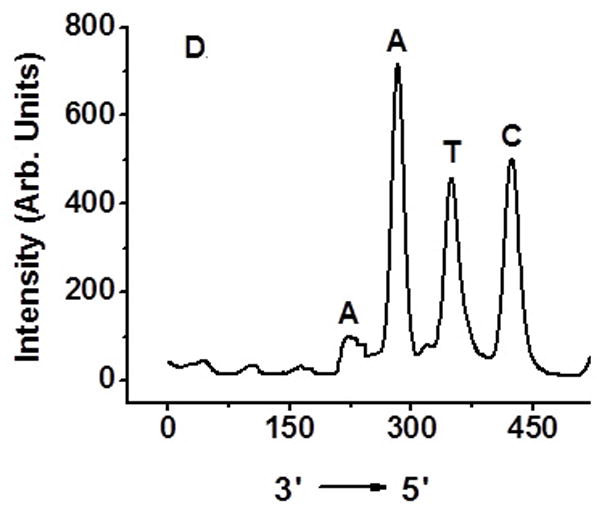

In an effort to determine the structure of the cross-linked product and possible side reactions, we used LC-mass to characterize the materials isolated from denaturing gel. A series of discrete peaks were observed, while the exact mass of ICL products was not obtained. Many peaks are smaller than the calculated mass of ICL product having nitroimidazole (9872.15), but larger than the calculated mass of ICL product losing nitroimidazole (9759.49 for 6 and 10) (SI, Figure S43 and S44). The differences between these peaks are usually 17 or 18, which indicates a hydroxyl group or a water molecule was added. For example, a peak of 9810 corresponds to the addition of three hydroxyl groups and 9830 corresponds to the addition of two water molecules and two hydroxyl groups (SI, Figure S43). This further prove the formation of thymine glycol and/or 5-hydroxyl-5,6-dihydropyrimidine derivatives and other DNA lesions with the addition of the hydroxyl group or water molecules. The alkaline labile lesions were also observed at the positions 20–23 of the complementary strand which is evidenced by the formation of the cleavage bands at these positions caused by the piperidine treatment of the ICL product (SI, lane 3 in Figure 3B, D and Figure 4B, D). During LC-mass analysis, the exact mass of 19 with an aldehyde on the 5-methyl group was observed (observed m/z = 4974.6056, calculated m/z = 4974. 2792) (Scheme 2 and SI, Figure S42). We believe that 19 is derived from the peroxyl radical 20, as proposed by Greenberg and Cadet.[12, 17]

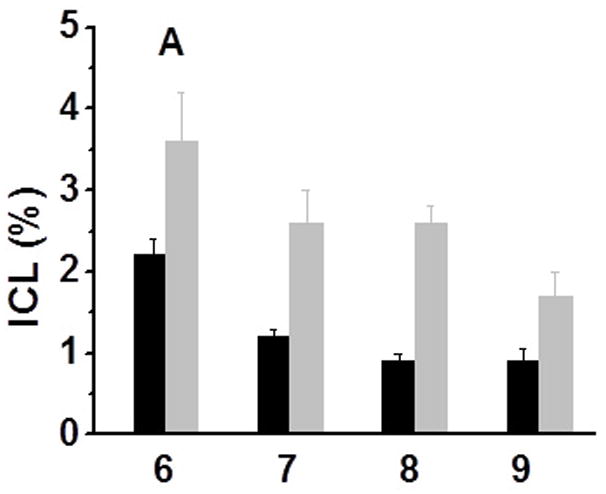

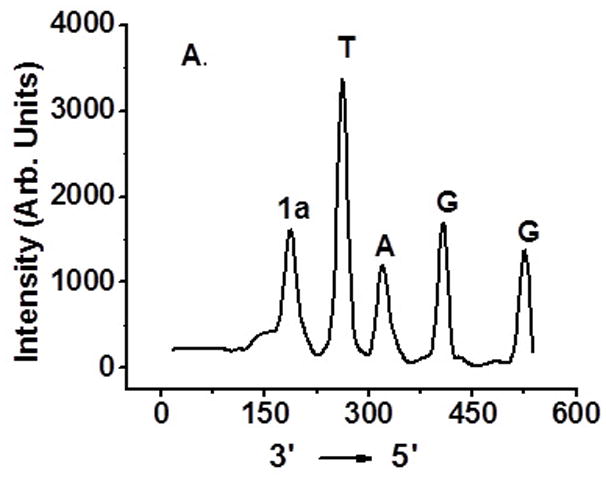

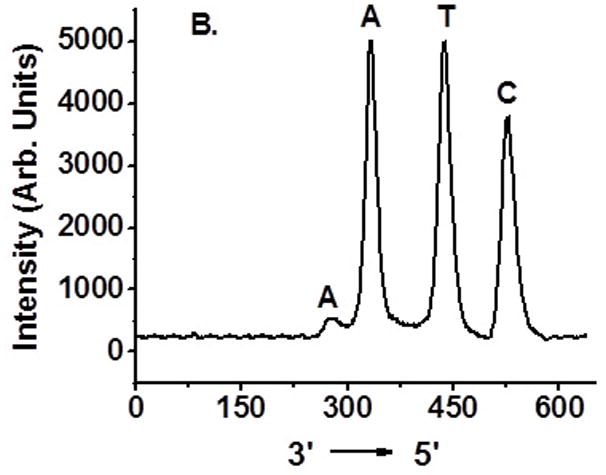

Figure 4.

Determination of interstrand cross-linking position via OH• cleavage of UV treated 6 and 10: (A) 5′-32P-6a, 4-nitroimidazole containing strand labeled; (B) 5′-32P-6b, complementary strand labeled; (C) 5′-32P-10a, 2-nitroimidazole containing strand labeled; (D) 5′-32P-10b, complementary strand labeled.

Scheme 2.

Products generated from 1a upon UV-photolysis.

Hydroxyl radical cleavage of gel-purified cross-linked DNA was used to determine which nucleotides were covalently bonded to one another.[11] Each oligonucleotide was either 5′-32P-labelled or 3′-32P-labelled. As expected, cross-linking occurred mainly with the position of 1a or 1b where 16 was generated (Figure 4A, C). The majority of the cross-links in the complementary strand involve reaction with dA23. Partial ICL took place with dA24 (Figure 4B, D and SI, Figure S47).

In summary, this work demonstrated that coupling of a hypoxia-radiosensitizer (e.g. nitroimidazoles) with a pyrimidine nucleoside allows for more efficient DNA interstrand cross-link formation under hypoxic conditions than that under aerobic conditions. The mechanism involves the release of a 5-(2′-deoxyuridinyl) methyl radical from a nucleoside radical anion which is generated via a photo-induced single electron transfer (PSET) within duplex DNA. The presence of oxygen quenches the radical anion therefore decreasing the ICL yield. Work is in progress to determine their hypoxia-selectivity in hypoxic cells, and their potential as hypoxia-targeting anticancer drugs.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Unless otherwise specified, chemicals were purchased from Aldrich or Fisher Scientific and were used as received without further purification. T4 polynucleotide kinase was obtained from New England Biolabs. Oligonucleotides were synthesized via standard automated DNA synthesis techniques using an Applied Biosystems model 394 instrument in a 1.0 μM scale using commercial 1000Å CPG-succinyl-nucleoside supports. Deprotection of the nucleobases and phosphate moieties as well as cleavage of the linker were carried out under mild deprotection conditions using a mixture of 40% aq. MeNH2 and 28% aq. NH3 (1:1) at room temperature for 2 h. Thermal denaturation temperatures (Tm values) were measured on a Cary 100 UV/Vis sepectrometer equipped with a thermoelectrical temperature controller. The temperature was changed at a rate of 1oC/min. Radiolabeling was carried out according to the standard protocols. [21][γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]ATP was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences. Quantification of radiolabeled oligonucleotides was carried out using a Molecular Dynamics Phosphorimager equipped with ImageQuant Version 5.2 software. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were taken on either a Bruker DRX 300 or DRX 500 MHz spectrophotometer. High resolution mass spectrometry was performed at the University of Kansas Mass Spectrometry Lab. ESI-MS for oligonucleotides and cross-linking DNA was determined by Center for Computational and Integrative Biology of Harvard Medical School.

Sample preparation under hypoxic conditions

For preparing samples under reduced O2 tension conditions, samples were degassed to remove the dissolved O2 using high vacuum pump (1 min), then purged with argon (1.0 min) (three cycles).

Interstrand cross-link formation and kinetics study with duplex DNA

The 32P-labelled oligonucleotide (1.0 μM) was annealed with 1.5 equiv of the complementary strand by heating to 65 °C for 3 min in buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 100 mM NaCl), followed by slow-cooling to room temperature overnight. The 32P-labeled oligonucleotide duplex (2 μL, 1.0 μM) was mixed with 1 M NaCl (2 μL), 100 mM potassium phosphate (2 μL, pH 7.5) and appropriate amount of autoclaved distilled water to give a final volume of 20 μL. The mixture was degassed to remove the air and purged with argon, then UV-irradiated in a Rayonet Photochemical Chamber Reactor (Model RPR-100, sixteen bulbs, 350 nm light wavelength) for 2h. The reaction was quenched by an equal volume of 90% formamide stop/loading buffer, then electrophoresed on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel at 1200 V for approximately 4 h. For kinetics study, aliquots (final concentration: 50 nM 32P-labeled oligonucleotide duplex, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM potassium phosphate) mixed with appropriate concentration of 2-mercaptoethanol were irradiated under argon for 2h and immediately quenched by 90% formamide loading buffer, and stored at −20 °C until subjecting to 20% denaturing PAGE analysis.

Hydroxyl radical reaction (Fe·EDTA reaction)

The cross-linked DNAs formed in duplexes 6 and 10 were purified by 20% denaturing PAGE. The band containing cross-linked product was cut, crushed, and eluted with 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA (2.0 mL). The crude product was further purified by C18 column eluting with H2O (3× 1.0 mL) followed by MeOH:H2O (3:2, 1.0 mL). Fe(II)·EDTA cleavage reactions of 32P-labelled oligonucleotide (0.1μM) were performed in a buffer containing 50 μM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, 100 μM EDTA, 5 mM sodium ascorbate, 0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 1 mM H2O2 for 3 min at room temperature (total substrate volume 20 μL), then quenched with 100 mM thiourea (10 μL). Samples were lyophilized, dissolved in 20 μL H2O: 90% formamide loading buffer (1:1) and subjected to 20% denaturing PAGE analysis.

Kinetic study of monomer reaction upon UV photolysis (350 nm)

Compound 1a or 1b (8 mg) was dissolved in a mixture of 0.93 mL DMSO-d6 and 0.07 mL D2O. The solution was equally divided into two portions which were placed in two NMR tubes. One sample was degassed to remove air under high vacuum, then purged with Ar2 for 5 min. Both samples were exposed to UV irradiation at 350 nm. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at different time (2, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 h for 1a; 5, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180, 240 min for 1b. The reaction yield was determined by calculating the decrease of the signal at 8.30 ppm which corresponds to imidazole. The peak at 2.50 ppm (DMSO) was used as a reference to quantify other peaks.

Stability study of ICL product formed with 6 or 10

After the cross-link reaction, the reaction mixtures (0.35 μM DNA duplex, 20 μL) were co-precipitated with calf thymus DNA (2.5 mg/mL, 5 μL) and NaOAc (3 M, 5 μL) in the presence of EtOH (90 μL) at −80°C for 30 min, followed by centrifuging for 5 min at 15000 rmp. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with cold 75% EtOH and lyophilized for 30 min in a Centrivap Concentrator of LABCONCO at 37 °C. The dried DNA fragments were dissolved in H2O (30 μL) and divided into three portions. One portion (10 μL) was incubated with piperidine (2 M, 10 μL) at 90°C for 30 min, and the second portion (10 μL) was incubated with 0.1 M NaCl and 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7, 10 μL) under the same condition, and the third portion was used as a control sample. The samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for the ICL formation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support of this research from the National Cancer Institute (1R15CA152914-01) and UWM start-up funds.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. Chem Rev. 2006;106:277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dronkert MLG, Kanaar R. Mutat Res. 2001;486:217–247. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. Br J Cancer. 1955;9:539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JM. Br J Radiol. 1979;52:650–656. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-52-620-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans SM, Hahn S, Pook DR, Jenkins WT, Chalian AA, Zhang P, Stevens C, Weber R, Weinstein G, Benjamin I, Mirza N, Morgan M, Rubin S, McKenna WG, Lord EM, Koch CJ. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Asquith JC, Foster JL, Willson RL, Ings R, McFadzean JA. Br J Radiol. 1974;47:474–481. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-47-560-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Buchko GW, Weinfeld M. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2186–2193. doi: 10.1021/bi00060a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Buchko GW, Weinfeld M. Radiat Res. 2002;158:302–310. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)158[0302:dtnsot]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JM, Wilson WR. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Tercel M, Wilson WR, Denny WA. J Med Chem. 1993;36:2578–2579. doi: 10.1021/jm00069a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wilson WR, Tercel M, Anderson RF, Denny WA. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1998;13:663–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Ogata R, Gilbert W. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1977;74:4973–4976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cecchini S, Girouard S, Huels MA, Sanche L, Hunting DJ. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1932–1940. doi: 10.1021/bi048105s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong IS, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10510–10511. doi: 10.1021/ja053493m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Hong IS, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3692–3693. doi: 10.1021/ja042434q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Millard JT, Weidner MF, Kirchner JJ, Ribeiro S, Hopkins PB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1885–1892. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.8.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Hong IS, Ding H, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:485–491. doi: 10.1021/ja0563657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hong IS, Ding H, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2230–2231. doi: 10.1021/ja058290c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Newcomb M. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:1151–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng X, Pigli YZ, Rice PA, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12890–12891. doi: 10.1021/ja805440v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantor GJ, Sutherland JC, Setlow RB. Photochem Photobiol. 1980;31:459–464. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy MB, Mandal PC, Basu S, Bhattacharyya SN. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1995;91:1191–1196. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Huang BS, Lauzon MJ, Parham JC. J Heterocyclic Chem. 1979;16:811–813. [Google Scholar]; b) Townsend LB. Chemistry of Nucleosides and Nucleotides. Vol. 3. Plenum Press; New York and London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Hong IS, Greenberg MM. Org Lett. 2004;6:5011–5013. doi: 10.1021/ol047754t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Romieu A, Bellon S, Gasparutto D, Cadet J. Org Lett. 2000;2:1085–1088. doi: 10.1021/ol005643y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Sugiyama H, Tsutsumi Y, Saito I. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6720–6721. [Google Scholar]; b) Cook GP, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10025–10030. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen T, Cook G, Koppisch AT, Greenberg MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3861–3866. [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Zhang Q, Wang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13287–13297. doi: 10.1021/ja048492t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang Q, Wang Y. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1897–1906. doi: 10.1021/tx050195u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang Y. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:671–676. doi: 10.1021/tx0155855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.vonSonntag C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology. Taylor & Francis; London: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Mannul. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1982. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.