Abstract

♦ Background: Peritoneal fibrosis is a serious complication of long-term peritoneal dialysis, and yet the precise pathogenic mechanisms of peritoneal fibrosis remain unknown. Fibrocytes participate in tissue fibrosis and express chemokine receptors that are necessary for migration. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway regulates the production of chemokines and has been demonstrated to contribute to the pathogenesis of various fibrotic conditions. Accordingly, we used an experimental mouse model of peritoneal fibrosis to examine the dependency of fibrocytes on p38MAPK signaling.

♦ Methods: Peritoneal fibrosis was induced in mice by the injection of 0.1% chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) into the abdominal cavity. Mice were treated with FR167653, a specific inhibitor of p38MAPK, and immunohistochemical studies were performed to detect fibrocytes and cells positive for phosphorylated p38MAPK. The involvement of p38MAPK in the activation of fibrocytes also was also investigated in vitro.

♦ Results: Fibrocytes infiltrated peritoneum in response to CG, and that response was accompanied by progressive peritoneal fibrosis. The phosphorylation of p38MAPK, as defined by CD45+ spindle-shaped cells, was detected both in peritoneal mesothelial cells and in fibrocytes. The level of peritoneal expression of CCL2, a chemoattractant for fibrocytes, was upregulated by CG injection, and treatment with FR167653 reduced the number of cells positive for phosphorylated p38MAPK, the peritoneal expression of CCL2, and the extent of peritoneal fibrosis. Pretreatment with FR167653 inhibited the expression of procollagen type I α1 induced by transforming growth factor-β1.

♦ Conclusions: Our results suggest that p38MAPK signaling contributes to peritoneal fibrosis by regulating fibrocyte function.

Keywords: Chemokine, fibrocytes, fibrosis, p38MAPK, peritoneum

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a beneficial treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease. Long-term PD treatment causes histopathologic alterations in the peritoneum, including fibrosis, which are associated with ultrafiltration failure and loss of dialytic capacity (1,2). Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) can also develop, which causes ileus; EPS is associated with high mortality (3). The precise pathogenic mechanisms that underlie the development of progressive peritoneal fibrosis remain unknown.

Circulating fibrocytes, which constitute a small fraction of the circulating pool of leukocytes, have been reported to be involved in various fibrotic diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, renal fibrosis, and hypertrophic scarring (4–7). Fibrocytes share markers of myeloid cells (for example, CD45 and CD34) and mesenchymal cells [for example, type I collagen (Col I) and fibronectin] (4–8). Additionally, fibrocytes express chemokine receptors (for example, CCR2, CCR5, CXCR4, and CCR7) that are involved in the recruitment of fibrocytes to sites of fibrosis (4–7,9). To date, the potential involvement of fibrocytes in peritoneal fibrosis has not been investigated.

The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) mediates an important intracellular signal transduction pathway by which signals from environmental stimuli are transmitted to the nucleus. At least 3 distinct groups of MAPKs have been identified: extracellular signal-regulated kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and p38MAPK (10). Activation of p38MAPK is involved in apoptosis, stress responses, and inflammation (10). Recent studies have revealed that p38MAPK phosphorylation is essential for the production of various chemokines, including monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1, also known as CCL2), and for the signal transduction of chemokine receptors such as CCR2, which is a cognate receptor for CCL2 (11–16). In addition, p38MAPK has been demonstrated to contribute to the pathogenesis of fibrotic conditions (17–21).

Taken together, the foregoing findings prompted us to examine the involvement of p38MAPK signaling in fibrocyte function and the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis. Using a well-known model of peritoneal fibrosis (22) induced in mice by intraperitoneal injection of chlorhexidine gluconate (CG), we evaluated the role of p38MAPK signaling with respect to fibrocyte function in the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis and whether blockade of p38MAPK signaling may be a beneficial approach for the treatment of progressive peritoneal fibrosis.

METHODS

MURINE MODEL OF PERITONEAL FIBROSIS

Inbred male C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks, 20 – 25 g) obtained from Charles River Japan (Atsugi, Japan) were divided into 4 groups. Peritoneal fibrosis was induced in 3 groups of the mice by intraperitoneal injection of 0.1% CG dissolved in 15% ethanol/saline every other day, over a period of 21 days as previously described (22,23). A specific p38MAPK inhibitor, FR167653 [16 mg/kg (FR16) and 32 mg/kg (FR32) daily], was dissolved in drinking water and orally administered to 2 of the CG groups starting 2 days before CG injection (15,16,24). Mice in each group (controls, n = 5; CG-only group, n = 9; CG+FR groups, n = 10) were humanely killed 21 days after the start of CG injection. All procedures used in the animal experiments complied with the standards set out in the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Kanazawa University.

TISSUE PREPARATION

One portion of peritoneal tissue from each mouse was fixed in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.2), embedded in paraffin, cut at 4 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Mallory–Azan and observed under a light microscope. The thickness of the submesothelial collagenous zone above the abdominal muscle layer in cross-sections of the abdominal wall was defined as the peritoneal thickness, as previously described (22). In each image, peritoneal thickness was measured at 10 different points. Peritoneal cross-sections were observed by 2 investigators and averaged to determine the reported peritoneal thickness. Measurements of peritoneal thickness were performed by image analysis using Mac SCOPE (version 6.02: Mitani Corporation, Fukui, Japan).

DETECTION OF FIBROCYTES IN PERITONEUM BY IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL STUDIES

Fibrocytes were identified in tissue samples by dual immunohistochemical techniques using specific antibodies against CD45 and Col I as previously described (5). For the present analysis, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections were prepared as previously described. Briefly, tissue sections were incubated with rat anti-mouse CD45 polyclonal antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and rabbit anti-mouse Col I polyclonal antibodies (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA). The CD45 was visualized by incubating sections with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated donkey anti-rat immunoglobulin G antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA). The Col I was visualized using Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Fibrocytes in peritoneum were counted in all fields of the submesothelial zone and expressed as the mean number ± standard error of the mean (SEM) per square millimeter. In addition, dual immunostaining for CCR2 and Col I was performed to characterize fibrocytes in the peritoneum. The tissue sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse CCR2 antibody (GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) and rabbit anti-mouse Col I polyclonal antibodies (Chemicon International). Fibrocytes positive for both CCR2 and Col I in peritoneum were counted in all fields of the submesothelial zone and expressed as the mean number ± SEM per square millimeter.

DETECTION OF PHOSPHORYLATED P38MAPK–POSITIVE CELLS

Immunohistochemistry for phosphorylated p38MAPK (p-p38MAPK) was performed to clarify the localization of cells positive for that marker. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse p-p38MAPK polyclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Mesothelial cells positive for p-p38MAPK were counted and expressed as a percentage of total mesothelial cells. In addition, immunostaining for CD45 and p-p38MAPK was performed to characterize the cells dually positive for those markers. Of the dual-positive cells, spindle-shaped cells that were positive for both CD45 and p-p38MAPK were regarded as fibrocytes positive for p-p38MAPK. Those cells were counted in all fields of the submesothelial zone and expressed as the mean number ± SEM per square millimeter.

DETECTION OF CCL2-POSITIVE CELLS

Immunohistochemistry for CCL2 was performed to clarify the localization of CCL2-positive cells. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with rat anti-mouse CCL2 polyclonal antibodies (Hycult Biotechnology, Uden, Netherlands).

ISOLATION OF HUMAN FIBROCYTES FROM PERIPHERAL BLOOD

Fibrocytes were harvested and cultured as previously reported (7). Briefly, centrifugation of venous blood drawn from healthy donors (n = 3) on a Ficoll–metrizoate density gradient [d = 1.077 g/mL (Lymphoprep: Nycomed, Oslo, Norway)] according to the manufacturer’s protocol was used to isolate total peripheral blood mononuclear cells. After 2 days of culturing in tissue-culture flasks containing Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium [DMEM (Gibco–BRL Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA] supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS (Gibco–BRL Life Technologies)], 100 U/mL penicillin (Gibco–BRL Life Technologies), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco–BRL Life Technologies), nonadherent cells were removed by gentle aspiration, and the media were replaced. After 10 – 12 days, adherent cells were lifted by incubation in ice-cold 0.05% EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline. The crude fibrocyte preparations then were depleted by immunomagnetic selection of contaminating T cells, B cells, and monocytes using pan-T, anti-CD2; pan-B, anti-CD19; and anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody–coated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Cell purity was verified by flow cytometry using both mouse anti-human CD45 monoclonal antibody [Becton Dickinson (PharMingen), Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA] and rabbit anti-human Col I polyclonal antibodies (Chemicon International).

CULTURE CONDITION OF FIBROCYTES

Purified fibrocytes were incubated with transforming growth factor β1 [TGFβ1 (R&D Systems)] in a time-dependent manner. Briefly, purified human fibrocytes (1×106/mL) were transferred to 12-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) containing DMEM supplemented with 0.5% heat-inactivated FCS (10 ng/mL) and were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in the presence of TGFβ1 for 0 – 24 hours. In parallel experiments, fibrocytes were pretreated with FR32 and then exposed to the TGFβ1.

REAL-TIME REVERSE-TRANSCRIPTASE POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION

To determine transcripts for the α1 chain of procollagen type I (Col Iα1) and CCL2 in the peritoneum, total RNA was extracted from whole peritoneum. Similarly, total RNA was extracted from cultured human fibrocytes and was analyzed for the detection of transcripts of Col Iα1. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed on the ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as previously described (5). Murine beta-glucuronidase and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase were used as polymerase chain reaction controls.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Means and SEMs were calculated for all parameters determined in this study. Statistical analyses used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, the Kruskal–Wallis test, and analyses of variance. A p value less than 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

EFFECT OF P38MAPK ON PERITONEAL FIBROSIS

Morphology changes were assessed by hematoxylin and eosin or Mallory–Azan staining. In normal mice, the peritoneal tissue consisted of a peritoneal mesothelial monolayer and an exiguity of connective tissues under the mesothelial layer [Figure 1(A)]. At day 21, the peritoneal samples of wild-type mice injected with CG showed marked thickening of the submesothelial compact zone and the presence of numerous cells [Figure 1(B)]. By contrast, the thickness of the submesothelial zone and the number of infiltrating cells for peritonea from CG+FR mice were significantly less than those from CG mice [Figure 1(C)]. The mean peritoneal thickness, as determined by computer analysis, was less in CG+FR mice than in CG mice [Figure 1(D)]. The effect of FR32 was more marked than that of FR16. Therefore, in subsequent examinations, the data relating to the CG+FR32 group were used. The expression of Col Iα1 messenger RNA (mRNA) in peritoneum also was less with FR treatment [Figure 1(E)].

Figure 1.

— Peritoneal thickness and type I collagen α1 (COLIAI) expression in the murine peritoneum. (A) Normal control at day 0 shows no evidence of peritoneal thickness (200× original magnification). (B) Peritoneal thickness at 21 days after the start of chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) injections (“CG mice”) (200× original magnification). (C) Peritoneal thickness at day 21 in mice treated with FR167653 (“CG+FR mice”) (200× original magnification). (D) Injection with CG caused the peritoneum to thicken in CG mice. By contrast, the peritoneum was less thick in CG+FR mice. (E) Upregulation of COLIAI messenger RNA expression was induced by CG injection and reduced with FR167653 treatment. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05.

FIBROCYTES DUALLY POSITIVE FOR CD45/COL I INFILTRATE THE PERITONEUM

As originally reported, one of the unique characteristics of fibrocytes is their simultaneous expression of CD45 and Col I (4–9). To examine peritoneum for the presence of fibrocytes, immunostaining for both CD45 and Col I was performed. Such dually positive fibrocytes infiltrated the peritoneum after CG injection [Figure 2(A-C)]. The number of infiltrating fibrocytes increased with the progression of fibrosis after CG injection, but increased less in CG+FR mice (231.6 ± 27.9/mm2) than in CG mice [616.0 ± 123.0/mm2, Figure 2(D)].

Figure 2.

— Fibrocyte infiltration into peritoneum. Dual immunostaining for CD45 and type I collagen (Col I) was performed (green = CD45; yellow = dual-positive fibrocyte (arrows); red = Col I). Dual-positive fibrocytes infiltrated peritoneum after chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) injection. (A) Normal control at day 0 (200× original magnification). (B) Mice injected with CG (200× original magnification). (C) Mice injected with CG and treated with FR167653 (CG+FR) (200× original magnification). Arrows indicate cells that are dually positive for CD45 and Col I. (D) The number of infiltrating fibrocytes was lower in mice treated with FR167653. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.01.

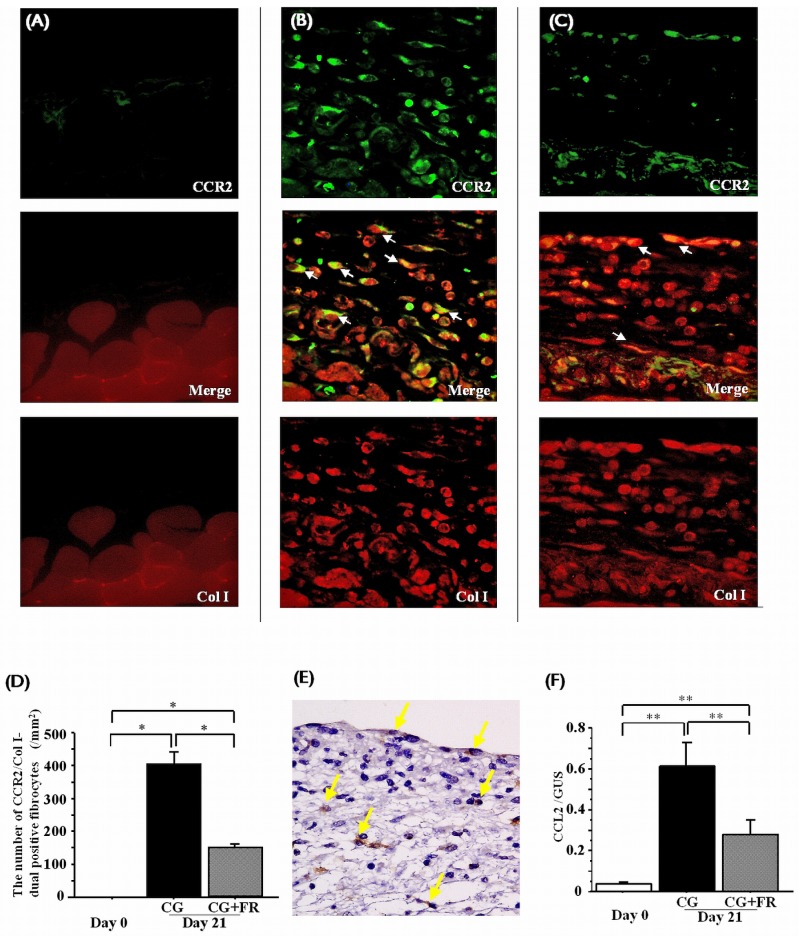

CCR2-EXPRESSING FIBROCYTES AND PERITONEAL CCL2 EXPRESSION IN PERITONEUM

To better characterize fibrocytes infiltrating into peritoneum, dual immunostaining for CCR2 and Col I was performed. Numerous CCR2-positive fibrocytes were detected in peritoneum after CG injection [Figure 3(A-C)]. The number of CCR2-positive fibrocytes increased with the progression of fibrosis after CG injection, but increased less in CG+FR mice (150.9 ± 13.3/mm2) than in CG mice [406.7 ± 39.8/mm2, Figure 3(D)].

Figure 3.

— Fibrocytes expressing CCR2, and CCL2 production, in peritoneum. Dual immunostaining for CCR2 and type I collagen (Col I) was performed (green = CCR2; yellow = CCR2-positive fibrocytes (arrows); red = Col I). Fibrocytes positive for CCR2 were detected in peritoneum after chlorhexidine gluconate (CG) injection. (A) Normal control at day 0. (B) Mice injected with CG. White arrows indicate cells positive for both CCR2 and Col I (200× original magnification). (C) Mice injected with CG and treated with FR167653 (CG+FR). White arrows indicate cells positive for both CCR2 and Col I (200× original magnification). (D) Fewer infiltrating CCR2-positive fibrocytes were observed in CG+FR mice. (E) Production of the CCL2 protein was induced by CG injection in peritoneal mesothelial cells as well as in interstitial cells. Yellow arrows indicate CCL2-positive cells (200× original magnification). (F) After CG injection, messenger RNA transcripts for CCL2 were upregulated in peritoneum; in CG+FR mice, levels of CCL2 were lower. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05.

To elucidate the effect of p-p38MAPK signaling on peritoneal chemotactic molecules, expression of CCL2 was examined. Injection of CG induced the CCL2 protein in peritoneal mesothelial cells and in interstitial cells [Figure 3(E)]. In peritoneum, mRNA transcripts for CCL2 were upregulated after CG injection, and levels of CCL2 were lower in CG+FR mice [Figure 3(F)].

CELLS IN THE PERITONEUM POSITIVE FOR PHOSPHORYLATED P38MAPK

Immunohistochemical studies were performed to clarify the localization of p-p38MAPK–positive cells in the peritoneum. After CG injection, positivity for p-p38MAPK was detected in peritoneal mesothelial cells as well as in interstitial cells in thickened peritoneum [Figure 4(A)]. The percentage of p-p38MAPK–positive mesothelial cells was higher in CG mice than in CG+FR mice [Figure 4(B)]. In addition, the number of p-p38MAPK–positive interstitial cells in peritoneum was less in CG+FR mice than in CG mice [Figure 4(C)].

Figure 4.

— The presence of cells positive for phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p-p38MAPK) in peritoneum. (A) Arrowheads indicate p-p38MAPK–positive mesothelial cells. Arrows indicate p-p38MAPK–positive spindle-shaped cells (200× original magnification). (B) The percentage of p-p38MAPK–positive mesothelial cells in peritoneum was lower in mice treated with FR167653 (CG+FR). (C) The number of p38MAPK-positive interstitial cells in peritoneum was significantly reduced in CG+FR mice. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.01.

CELLS DUALLY POSITIVE FOR CD45 AND PHOSPHORYLATED P38MAPK IN PERITONEUM

To confirm the identity of peritoneal p-p38MAPK–positive cells, dual immunostaining for CD45 and p-p38MAPK was performed. A portion of these dually positive cells were spindle-shaped cells, suggesting the presence of p-p38MAPK–positive fibrocytes [Figure 5(A–C)]. The number of spindle-shaped cells dually positive for CD45 and p-p38MAPK in peritoneum was lower in CG+FR mice than in CG mice [Figure 5(D)].

Figure 5.

— Characterization of peritoneal cells positive for phosphorylated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p-p38MAPK). Dual immunostaining for CD45 and p-p38MAPK was performed (brown = p-p38MAPK; red = CD45). Arrows indicate spindle-shaped cells positive for CD45 and p-p38MAPK. (A) Normal control at day 0 (200× original magnification). (B) Mice injected with CG (200× original magnification). (C) Mice injected with CG and treated with FR167653 (CG+FR) (200× original magnification). (D) The number of spindle-shaped cells positive for CD45 and p-p38MAPK was lower in CG+FR mice. Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05.

PRODUCTION OF COL IA1 MRNA IN ISOLATED FIBROCYTES WAS REDUCED WITH FR167653 TREATMENT

The impact of p38MAPK signaling on Col Iα1 expression in isolated fibrocytes was examined in vitro. Circulating fibrocytes isolated from human peripheral blood (>97% pure population of cells co-expressing CD45 and Col I) were cultured in DMEM and 0.5% heat-inactivated FCS for 24 hours and were then stimulated with TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) for 24 hours. Stimulation with TGFβ1 increased the expression of Col Iα1; pretreatment with FR167653 abrogated the TGFβ1-induced expression of Col Iα1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

— The effect of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase on production of procollagen type I α1 (COLIAI). Stimulation with transforming growth factor β1 (TGF) induced isolated fibrocytes to produce COLIAI messenger RNA, an effect that was reduced by treatment with FR167653 (FR). Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. * p < 0.05. GAPDH = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

DISCUSSION

Using a murine model of peritoneal fibrosis, the present study provides evidence for infiltration by fibrocytes into peritoneum. The number of fibrocytes in peritoneum increased in accordance with the progression of peritoneal fibrosis. The infiltrating fibrocytes expressed the chemokine receptor CCR2, and an increase in p-p38MAPK was detected in peritoneal mesothelial cells and interstitial cells, including fibrocytes. The number of cells positive for p-p38MAPK and the level of peritoneal CCL2 expression were associated with the severity of fibrosis. Pharmacologic inhibition of p38MAPK signaling reduced the extent of fibrosis, the numbers of fibrocytes and of p-p38MAPK–positive cells, and the peritoneal expression of CCL2. Furthermore, inhibition of p38MAPK signaling attenuated the expression of Col Iα1 induced by TGFβ1 stimulation of cultured fibrocytes. These results suggest that the p38MAPK pathway contributes to the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis through activation of and infiltration by fibrocytes.

Activation of p38MAPK signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of renal and pulmonary fibrosis through the upregulation of proinflammatory mediators (10,11,17,18,20,21,25). The phosphorylation of p38MAPK has been demonstrated in resident cells, including renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) both in an experimental model of renal fibrosis and in human renal diseases (20,21). The present study also revealed phosphorylation of p38MAPK in peritoneal mesothelial cells. Not only peritoneal mesothelial cells but also RTECs have been reported to be capable of producing chemokines via p38MAPK signaling cascades (26,27). The number of p-p38MAPK–positive cells and the level of CCL2 expression in mesothelial cells both increased concomitantly with progression of fibrosis, and treatment with FR167653 reduced those changes. Based on those findings, p38MAPK may contribute to the production of CCL2 in peritoneal mesothelial cells, thereby promoting the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis.

The infiltration of fibrocytes into diseased organs has been reported to be regulated by chemokine–chemokine receptor systems, including CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 (4–6,9,28). In addition, inhibition of the CCR2–CCL2 system has been shown to ameliorate the infiltration of fibrocytes and the severity of fibrosis in a murine pulmonary fibrosis model (9). In the present study, blockade of p38MAPK signaling reduced the number of CCR2-expressing fibrocytes in accord with levels of CCL2 expression and with the intensity of peritoneal fibrosis, suggesting that the CCR2–CCL2 system depends on p38MAPK. The potential roles of other chemokine systems, including CCR7–CCL21 and CXCR4–CXCL12, in the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis remain to be determined.

Finally, we observed that the expression of Col Iα1 in cultured fibrocytes was enhanced by stimulation with TGFβ1 and that pretreatment with FR167653 abrogated the expression of Col Iα1. Thus, p38MAPK signaling may also contribute to the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis by directly regulating the production of collagen in fibrocytes. Such a pathway has previously been suggested in studies of procollagen type I and fibronectin expression by scleroderma fibroblasts (29). Furthermore, CCR2-expressing fibrocytes have been shown, in a murine pulmonary fibrosis model, to express type I procollagen in response to stimulation with CCL2 (9).

CONCLUSIONS

Our results suggest that p38MAPK signaling is involved in the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis through the regulation of fibrocyte infiltration and collagen production (Figure 7). Inhibition of the recruitment and activation of fibrocytes by p38MAPK signal transduction could provide a novel therapeutic approach for combating organ fibrosis.

Figure 7.

— Proposed schema for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38MAPK) signaling in the pathogenesis of peritoneal fibrosis: regulation of fibrocyte infiltration by production of CCL2 (a chemoattractant for fibrocytes), and production of collagen in fibrocytes.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Richard Bucala (Yale University) for careful review of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sport and Culture of Japan (TW, NS), the Takeda Science Foundation (TW), and the Japan Baxter PD Fund (NS).

REFERENCES

- 1. Selgas R, Fernandez–Reyes MJ, Bosque E, Bajo MA, Borrego F, Jimenez C, et al. Functional longevity of the human peritoneum: how long is continuous peritoneal dialysis possible? Results of a prospective medium long-term study. Am J Kidney Dis 1994; 23:64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies SJ, Bryan J, Phillips L, Russell GI. Longitudinal changes in peritoneal kinetics: the effects of peritoneal dialysis and peritonitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11:498–506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cnossen TT, Konings CJ, Kooman JP, Lindholm B. Peritoneal sclerosis—aetiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21(Suppl 2):ii38–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, et al. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2004; 114:438–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakai N, Wada T, Yokoyama H, Lipp M, Ueha S, Matsushima K, et al. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC/CCL21)/CCR7 signaling regulates fibrocytes in renal fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:14098–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol 2001; 166:7556–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sakai N, Wada T, Matsushima K, Bucala R, Iwai M, Horiuchi M, et al. The renin–angiotensin system contributes to renal fibrosis through regulation of fibrocytes. J Hypertens 2008; 26:780–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med 1994; 1:71–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moore BB, Kolodsick JE, Thannickal VJ, Cooke K, Moore TA, Hogaboam C, et al. CCR2-mediated recruitment of fibrocytes to the alveolar space after fibrotic injury. Am J Pathol 2005; 166:675–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang XS, Diener K, Manthey CL, Wang S, Rosenzweig B, Bray J, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:23668–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakai N, Wada T, Furuichi K, Iwata Y, Yoshimoto K, Kitagawa K, et al. p38 MAPK phosphorylation and NF-kappa B activation in human crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17:998–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rovin BH, Wilmer WA, Danne M, Dickerson JA, Dixon CL, Lu L. The mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 is necessary for interleukin 1β-induced monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 expression by human mesangial cells. Cytokine 1999; 11:118–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goebeler M, Kilian K, Gillitzer R, Kunz M, Yoshimura T, Bröcker EB, et al. The MKK6/p38 stress kinase cascade is critical for tumor necrosis factor-α–induced expression of monocyte chemo chemoattractant protein-1 in endothelial cells. Blood 1999; 93:857–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Furuichi K, Wada T, Iwata Y, Sakai N, Yoshimoto K, Kobayashi Ki K, et al. Administration of FR167653, a new anti-inflammatory compound, prevents renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17:399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwata Y, Wada T, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Matsushima K, Yokoyama H, et al. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase contributes to autoimmune renal injury in MRL–Fas lpr mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14:57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wada T, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Iwata Y, Yoshimoto K, Shimizu M, et al. A new anti-inflammatory compound, FR167653, ameliorates crescentic glomerulonephritis in Wistar–Kyoto rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11:1534–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wada T, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Hisada Y, Kobayashi K, Mukaida N, et al. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase followed by chemokine expression in crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 38:1169–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wada T, Azuma H, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Kitagawa K, Iwata Y, et al. Reduction in chronic allograft nephropathy by inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Am J Nephrol 2006; 26:319–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sato M, Shegogue D, Gore EA, Smith EA, McDermott PJ, Trojanowska M. Role of p38 MAPK in transforming growth factor beta stimulation of collagen production by scleroderma and healthy dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 2002; 118:704–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stambe C, Atkins RC, Tesch GH, Masaki T, Schreiner GF, Nikolic–Paterson DJ. The role of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15:370–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sakai N, Wada T, Furuichi K, Iwata Y, Yoshimoto K, Kitagawa K, et al. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 in human diabetic nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45:54–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tanabe K, Maeshima Y, Ichinose K, Kitayama H, Takazawa Y, Hirokoshi K, et al. Endostatin peptide, an inhibitor of angiogenesis, prevents the progression of peritoneal sclerosis in a mouse experimental model. Kidney Int 2007; 71:227–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishii Y, Sawada T, Shimizu A, Tojimbara T, Nakajima I, Fuchinoue S, et al. A experimental sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis model in mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001; 16:1262–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iwata Y, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Yamauchi H, Shinozaki Y, Zhou H, et al. Dendritic cells contribute to autoimmune kidney injury in MRL-Faslpr mice. J Rheumatol 2009; 36:306–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsuoka H, Arai T, Mori M, Goya S, Kida H, Morishita H, et al. A p38 MAPK inhibitor, FR-167653, ameliorates murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 283:L103–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsuo H, Tamura M, Kabashima N, Serino R, Tokunaga M, Shibata T, et al. Prednisolone inhibits hyperosmolarity-induced expression of MCP-1 via NF-kappaB in peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int 2006; 69:736–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ho AW, Wong CK, Lam CW. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha up-regulates the expression of CCL2 and adhesion molecules of human proximal tubular epithelial cells through MAPK signaling pathways. Immunobiology 2008; 213:533–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wada T, Sakai N, Matsushima K, Kaneko S. Fibrocytes: a new insight into kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int 2007; 72:269–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ihn H, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Increased phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 in scleroderma fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125:247–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]