Abstract

♦ Background: Peritoneal membrane damage induced by peritoneal dialysis (PD) is largely associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells (MCs), which is believed to be a result mainly of the glucose degradation products (GDPs) present in PD solutions.

♦ Objectives: This study investigated the impact of bicarbonate-buffered, low-GDP PD solution (BicaVera: Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) on EMT of MCs in vitro and ex vivo.

♦ Methods: In vitro studies: Omentum-derived MCs were incubated with lactate-buffered standard PD fluid or BicaVera fluid diluted 1:1 with culture medium.

Ex vivo studies: From 31 patients randomly distributed to either standard or BicaVera solution and followed for 24 months, effluents were collected every 6 months for determination of EMT markers in effluent MCs.

♦ Results: Culturing of MCs with standard fluid in vitro resulted in morphology change to a non-epithelioid shape, with downregulation of E-cadherin (indicative of EMT) and strong induction of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. By contrast, in vitro exposure of MCs to bicarbonate/low-GDP solution had less impact on both EMT parameters.

Ex vivo studies partially confirmed the foregoing results. The BicaVera group, with a higher prevalence of the non-epithelioid MC phenotype at baseline (for unknown reasons), showed a clear and significant trend to gain and maintain an epithelioid phenotype at medium- and longer-term and to show fewer fibrogenic characteristics. By contrast, the standard solution group demonstrated a progressive and significantly higher presence of the non-epithelioid phenotype. Compared with effluent MCs having an epithelioid phenotype, MCs with non-epithelioid morphology showed significantly lower levels of E-cadherin and greater levels of fibronectin and VEGF. In comparing the BicaVera and standard solution groups, MCs from the standard solution group showed significantly higher secretion of interleukin 8 and lower secretion of collagen I, but no differences in the levels of other EMT-associated molecules, including fibronectin, VEGF, E-cadherin, and transforming growth factor β1.

Peritonitis incidence was similar in both groups. Functionally, the use of BicaVera fluid was associated with higher transport of small molecules and lower ultrafiltration capacity.

♦ Conclusions: Effluent MCs grown ex vivo from patients treated with bicarbonate/low-GDP BicaVera fluid showed a trend to acquire an epithelial phenotype, with lower production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (such as interleukin 8) than was seen with MCs from patients treated with a lactate-buffered standard PD solution.

Keywords: Biocompatibility, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, bicarbonate peritoneal dialysis fluid, glucose degradation products, mesothelial cells

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an established dialysis technique used by approximately 11% of patients with end-stage renal disease worldwide (1); however, chronic exposure of the peritoneum to PD fluids causes local inflammation and leads to peritoneal dysfunction and membrane failure (2,3). The loss of the membrane’s dialysis capacity is responsible for increased morbidity and mortality.

The non-physiologic nature of PD fluids is considered to be one of the factors leading to alteration of the peritoneal membrane (3). This persistent stress of chronic peritoneal inflammation, exacerbated by periodic acute episodes of peritonitis, contributes to structural abnormalities of the peritoneal membrane, including loss of the mesothelial cell (MC) monolayer, submesothelial fibrosis, angiogenesis, and hyalinizing vasculopathy (4,5). Such alterations are considered to be the major cause of loss of functional membrane capacity, resulting in ultrafiltration (UF) failure.

Characterization of this response to PD is based on functional, histologic, and cytologic effluent studies (6). Peritoneal biopsy is the accepted standard for investigating peritoneal membrane alterations, but its invasiveness precludes regular use. Based on histologic data, we showed that epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of MCs is the mechanism that probably initiates damage to the membrane (7–10). Transdifferentiated MCs acquire a non-epithelioid phenotype, with loss of E-cadherin and increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibronectin, and collagen I (7–9), all of which correlate with high peritoneal transport (7). We also demonstrated that standard fluids induce EMT of MCs in vitro (7,8).

BicaVera (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) is a bicarbonate-buffered PD fluid with a low content of glucose degradation products (GDPs) relative to standard solutions (11). The first clinical studies have suggested improved biocompatibility for this solution (12,13). Glucose degradation products promote the transformation of precursors of glycosylation (Amadori products) into advanced glycosylation endproducts (AGEs) (14). Mesothelial cells express the AGE receptor (RAGE), and RAGE activation is able to initiate EMT (15). In two series of PD patients, Do and coworkers (16,17) showed rapid remesothelialization and less EMT with the use of low-GDP solutions at the medium term. Based on those data and on our experience with another low-GDP fluid (18), we hypothesized that peritoneal MCs of patients exposed to a GDP-reduced fluid with bicarbonate as buffer (BicaVera) should show an additionally lower risk of EMT development and, by extension, less deteriorated peritoneal function, both in vitro and ex vivo, than is seen with exposure to lactate/GDP-rich standard fluid. The aim of the present study was therefore to examine whether expression of EMT markers in MCs from effluents of PD patients is reduced by treatment with bicarbonate/low-GDP solution (BicaVera) at the medium term.

METHODS

PATIENTS AND STUDY DESIGN

Two parallel studies to evaluate low-GDP fluids with different buffers—Balance (Fresenius Medical Care) and BicaVera—were simultaneously performed, with both fluids being compared with a standard fluid (Stay·Safe: Fresenius Medical Care). The results obtained with Balance and with the standard fluid have already been published (18).

The present prospective study was performed over a 4-year period in two university hospitals using the same PD protocols (19). Only incident patients were included, and the only inclusion criterion was that patients be able and willing to perform continuous ambulatory PD therapy with no expressed indication for automated PD. Patients were randomly assigned to either BicaVera or the standard PD fluid by the doctors. The standard-fluid (Stay·Safe; 1.5%, 2.3%, and 4.25% glucose) group consisted of 20 patients (11 women, 9 men; mean age: 59 ± 15 years; 15% with diabetes); the BicaVera (1.5%, 2.3%, and 4.25% glucose) group consisted of 11 patients (3 women, 8 men; mean age: 68.22 ± 8.80; 38% with diabetes). All patients were starting PD de novo, and every patient in a particular PD group received the same PD solution from the start of PD. The first functional evaluation of the membrane was done before the second month on PD, and that evaluation was considered to be the baseline. The follow-up period for each patient was planned to be 24 months. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committees of both hospitals. Written informed consent was given by the patients.

Peritoneal transport of water and small solutes was determined during a 4-hour peritoneal kinetic study performed using the 4.25% glucose version of the fluid to which the patient had been allocated. The patient’s mass transfer area coefficient (MTAC) for creatinine, UF capacity for the same period, and residual renal function (RRF) were calculated as previously described (20). Every 6 months, we determined EMT markers in MCs released into nocturnal peritoneal effluent. When a peritonitis or hemoperitoneum occurred, samples were taken after a 4-week symptom-free period.

MC CULTURES AND TREATMENTS

Human peritoneal MCs were isolated from the effluent of overnight dwells with the 2.3% glucose version of the fluid to which the patient had been allocated, using the previously described method (21). These effluent-derived MCs were cultured until 100% confluence in Earle M199 medium (Biological Industries, Ashraf, Israel) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco–BRL Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland), 50 IU/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mol/L 2% HEPES, 10 μg/mL ciprofloxacin (Bristol–Myers Squibb, Columbus, OH, USA), and 2% Biogro-2 (Biological Industries). Markers of EMT were determined ex vivo (21).

The in vitro experiments used omentum-derived MCs that were isolated and cultured as previously described (21), remaining stable for 1 – 2 passages. Oral informed consent for the collection of omental MCs was obtained from nonuremic patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery.

To exclude contamination by fibroblasts, the purity of the omentum- and effluent-derived human MC cultures was determined by measuring the expression of standard mesothelial markers (8). These MC cultures were negative for von Willebrand factor, thereby excluding endothelial cell contamination (21). Confluent omentum-derived MCs were incubated for 48 – 72 hours in both standard (Stay·Safe 2.3% glucose) and bicarbonate (BicaVera 2.3% glucose) PD solutions diluted 1:1 with culture medium. As controls, omentum-derived MCs were cultured with M199 0% fetal bovine serum diluted 1:1 with culture medium. Some MCs in control cultures were also treated with recombinant human transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) 1 ng/mL (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) to induce EMT in vitro (8). Each experiment was carried out in duplicate, and at least 5 experiments were performed.

The morphology of effluent-derived MCs was assessed at 100% confluence. Each culture of effluent MCs reached confluence at a different time, but always at less than 1 month. Confluent MC cultures from PD effluent were classified into epithelioid and non-epithelioid groups according to their cellular morphology and expression of extracellular matrix components, as previously described (8).

WESTERN BLOT

Cultures of MCs were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) with an inhibitors cocktail (Pierce, Cambridge, MA, USA), and total protein was quantified using a total-protein assay kit (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein (30 – 50 μg) were fractionated using 8% – 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Membranes were blocked with nonfat milk and incubated with specific antibodies against E-cadherin (Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) and tubulin (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) was visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce), and blot images were acquired using a Kodak Image Station 2000MM (Eastman Kodak, New York, NY, USA).

QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME POLYMERASE CHAIN REACTION ANALYSIS

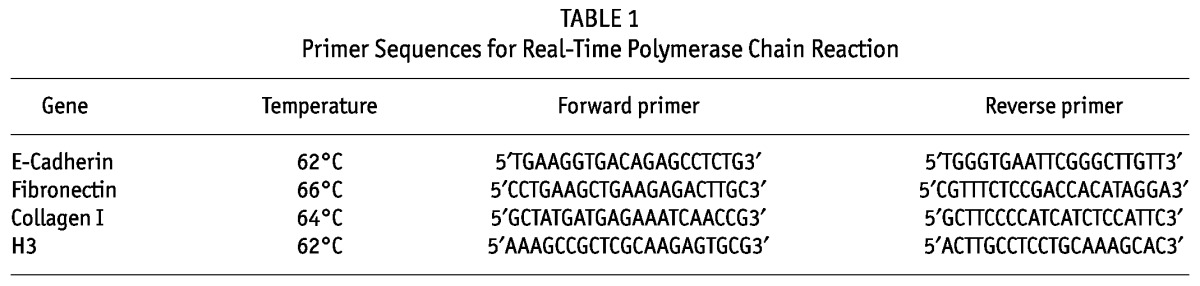

For reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, MCs were lysed in TRI Reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA was obtained from 2 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription (RNA PCR Core Kit: Applied Biosystems, by Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Quantitative PCR was carried out in a Light Cycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) using a SYBR Green PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics) and specific primers sets for E-cadherin, fibronectin, and collagen I. Histone 3 primers were used as a PCR reaction control (Table 1). These studies were performed using MCs from patients in both groups who had reached at least 18 months of treatment.

TABLE 1.

Primer Sequences for Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

ENZYME-LINKED IMMUNOASSAY

For the detection of VEGF, interleukin 8 (IL-8), and active TGF-β1 in culture supernatants, media of MCs cultured under the earlier described conditions were replaced and collected 18 hours later; supernatants were stored at –80°C until analysis. The VEGF, IL-8, and TGF-β1 concentrations in supernatants were determined using ELISA kits (R&D Systems). Levels of fibronectin, procollagen, and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 in cell lysates were also assessed using commercially available ELISA kits (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA; Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan; and Diaclone, Besaçon, France respectively) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Results were normalized according to the total protein in the cell lysate.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Comparisons between data groups were performed using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney rank sum U-test. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Wilcoxon test was used for intragroup comparisons between periods, and the Mann–Whitney test was used for between-group comparisons.

To study the complete outcome of each variable over time, we applied a linear mixed model using an unstructured covariance matrix for quantitative variables and generalized estimating equations for qualitative variables (phenotype), both in the framework of generalized mixed models. The results should be interpreted as follows:

“Significant model” means that the fluid–time interaction is p < 0.01.

“Significant fluid” means that the effects of the two fluids are different, but that the variation over time is not significantly different (parallelism maintained).

“Significant time” means that both fluids are affected by time to similar degrees.

To remove the interference of peritonitis from the studied variables, we applied three different approaches to the linear mixed-model analysis:

Isolated analysis of the outcomes of patients who never experienced peritonitis compared with those who experienced at least 1 episode

Comparison of samples collected before and after the first peritonitis episode, with the introduction of peritonitis as a covariate

Introducing peritonitis (1 episode vs 0 episodes, cumulative episodes, and days of peritoneal inflammation) as other covariates in the generalized estimating equations

Analysis of variance was used to establish the distribution of continuous variables between populations.

We used the SPSS software application (version 14.5: SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), which contains details on generalized mixed models, their method, and their meaning, and GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Sof tware, La Jolla, CA, USA) for the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

CHARACTERIZATION OF EFFLUENT-DERIVED MC CULTURES

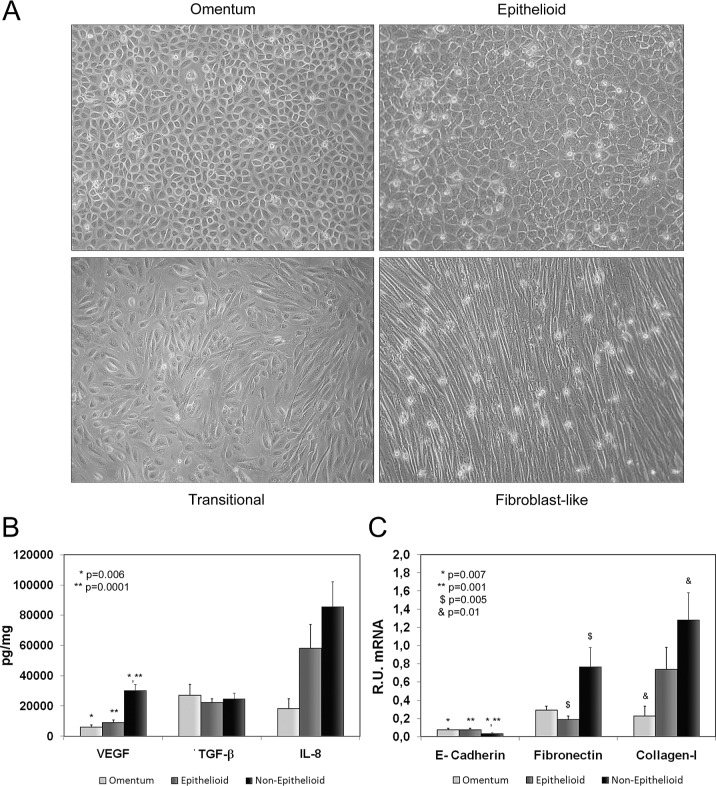

As previously described (7,8), cultures of effluent MCs can potentially show three different phenotypes: epithelial-like (similar to that of omentum-derived MCs), transitional, and fibroblast-like [Figure 1(A)]. Because of similitude in EMT markers, we group transitional and fibroblast-like MCs into a single category, “non-epithelioid MCs.” Using that approach, we have always grouped confluent MC cultures into epithelioid and non-epithelioid MC groups, according not only to their morphologic characteristics, but also to their expression of EMT markers. Furthermore, we use ELISA to measure levels of several markers—VEGF, TGF-β1, IL-8—to better classify confluent MCs.

Figure 1.

— Characterization of effluent-derived mesothelial cells (MCs). (A) Omentum-derived and the three possible morphologies (epithelial-like, transitional, fibroblast-like) of effluent-derived confluent MCs. Because of similarity in their markers of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), we grouped transitional and fibroblast-like MCs into a single category: non-epithelioid MCs. (B) Expression levels of EMT markers in supernatants: in non-epithelioid MCs, levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin 8 (IL-8) were seen to be increased [p = 0.0001 and 0.089 (not shown) respectively], but levels of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) were not. (C) In non-epithelioid (compared with omentum-derived) MCs, we found a significant downregulation of E-cadherin (p = 0.001) messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and an important upregulation of fibronectin (p = 0.005) and collagen I (p = 0.01) mRNA expression. R.U. = relative units.

Compared with MCs from omentum, non-epithelioid MCs showed increased expression of VEGF (p = 0.0001) and IL-8. We did not find upregulation of TGF-β1. In addition, in non-epithelioid MCs, quantitative PCR showed significant downregulation of E-cadherin (p = 0.001) and important upregulation of fibronectin (p = 0.005) and collagen I [p = 0.01, Figure 1(B,C)]. In epithelioid MCs compared with MCs from omentum, we also observed upregulation in most EMT markers because, as previously demonstrated, that transition is already ongoing in epithelioid effluent-derived MCs (8).

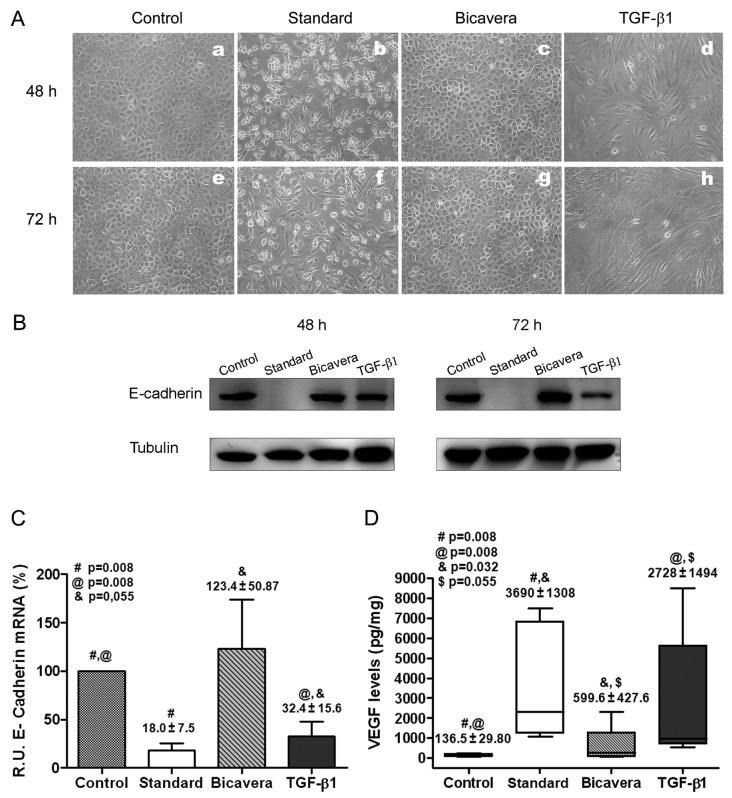

Exposure of MCs to bicarbonate/low-GDP fluid (BicaVera) in vitro had less impact on EMT than did exposure to lactate-buffered standard fluid. The omentum-derived MCs were incubated for 48 or 72 hours with 2.3% glucose standard (Stay·Safe) or bicarbonate/low-GDP (BicaVera) PD fluid diluted 1:1 with culture medium. Positive and negative EMT control MCs were also cultured. Exposure of MCs to standard PD fluid resulted in marked cell death (floating round-shaped cells) and in morphologic change at 48 and 72 hours, with the acquisition of a spindle-like shape, similar to that of TGF-β1–treated cells [positive control, Figure 2(A)]. By contrast, no effect on cellular viability or morphology was observed after exposure of MCs to BicaVera. In addition, treatment of MCs with standard PD fluid or with TGF-β1 resulted in downregulation of E-cadherin, which is indicative of EMT. Interestingly, incubation of MCs with BicaVera preserved the expression of E-cadherin [Figure 2(B)]. Those data were confirmed in a more quantitative manner by real-time PCR measurement of expression levels of E-cadherin mRNA. Exposure of omentum-derived MCs to standard PD fluid or to TGF-β1 for 72 hours significantly suppressed the expression of E-cadherin mRNA [Figure 2(C)]. In accord with the earlier results of E-cadherin protein expression, MCs exposed to BicaVera showed preserved expression of E-cadherin mRNA [Figure 2(C)].

Figure 2.

— Effects of peritoneal dialysis (PD) fluids on mesothelial cells (MCs) in vitro. (A) Effects on MC morphology at 48 and 72 hours. Images are representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) Western blot results show expression of E-cadherin in exposed MCs. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Images are representative of 5 independent experiments. (C) Levels of E-cadherin messenger RNA (mRNA) analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction [for MCs treated with PD fluids or with transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) relative to untreated cells]. Results are mean ± standard error of 5 experiments. (D) Production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in supernatant (picograms per milligram of cell protein) by omentum-derived MCs treated with PD fluids or with TGF-β1. The box plots show 75th percentile, 25th percentile, median, maximum, and minimum values from 5 experiments. BicaVera: solution from Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany. R.U. = relative units.

To further explore the effects of exposure to PD fluid on EMT, we analyzed the expression of VEGF, which has been shown to be upregulated during the mesenchymal conversion of MCs (7,9). As Figure 2(D) shows, exposure of MCs to standard PD fluid or to TGF-β1 significantly induced the secretion of VEGF; MCs exposed to BicaVera did not show significant upregulation of VEGF.

CLINICAL COURSE OF PATIENTS

In the standard and BicaVera fluid groups, 20 and 11 patients respectively were followed for 6 months, 18 and 11 for 12 months, 11 and 11 for 18 months, and 3 and 5 for 24 months. Technique survival was similar in both fluid groups. The reasons for drop-out were kidney transplantation in 7 (standard-fluid) and 2 (BicaVera) patients, transfer to hemodialysis in 5 and 3 patients, transfer to automated PD in 3 and 0 patients, and death in 1 patient in each group.

The percentage of patients affected by peritonitis was similar in both groups: 9 episodes occurred in the standard group (3 episodes in 1 patient, and 1 episode in each of 6 patients), and 9 episodes in the BicaVera group (3 episodes in 1 patient, 2 episodes in each of 2 patients, and 1 episode in each of 4 patients). The time to first peritonitis episode in each group was not significantly different (data not shown). The global peritonitis incidence was slightly but not significantly higher in the BicaVera group (1 episode in 25 patient–months vs 1 episode in 30 patient–months in the standard group).

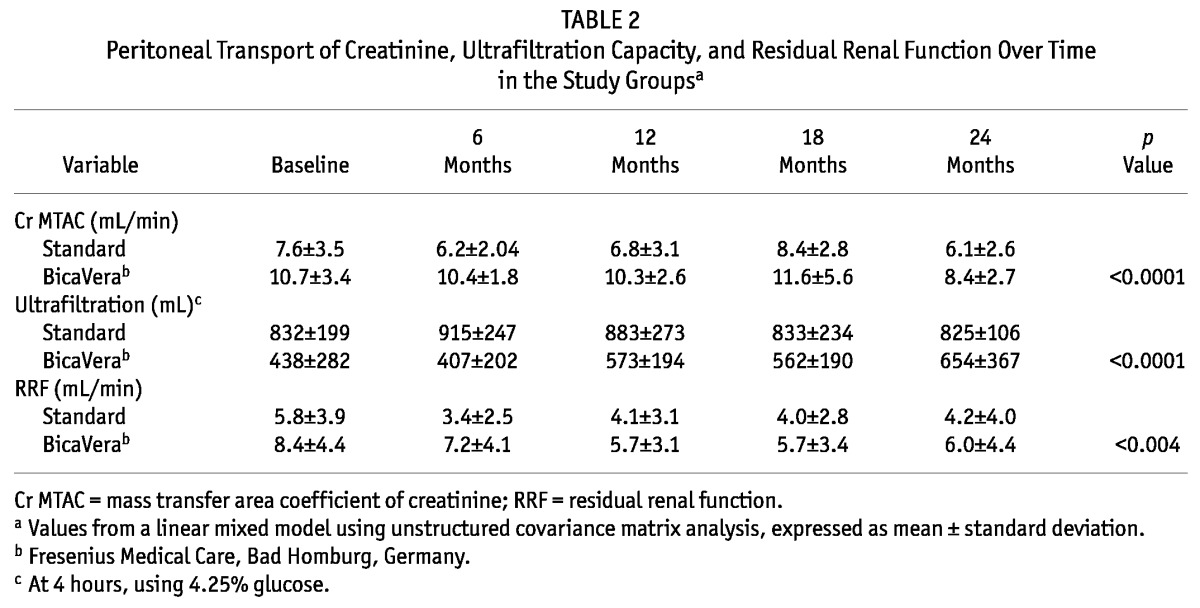

In studies of peritoneal function and RRF, the BicaVera group showed higher small-solute transport and lower UF. The linear mixed model using an unstructured covariance matrix for quantitative variables showed, for the fluids alone, higher values for the creatinine MTAC (p < 0.0001) and RRF (p < 0.004) and lower values for the UF capacity (p < 0.0001) in the BicaVera group; however, the fluid–time interaction was not statistically significant (Table 2). Pre-PD RRF values were also higher in the BicaVera group (10.33 mL/min vs 6.06 mL/min in the standard-fluid group). The dialysate-to-plasma ratio of creatinine and the diuresis were similar in both groups (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Peritoneal Transport of Creatinine, Ultrafiltration Capacity, and Residual Renal Function Over Time in the Study Groupsa

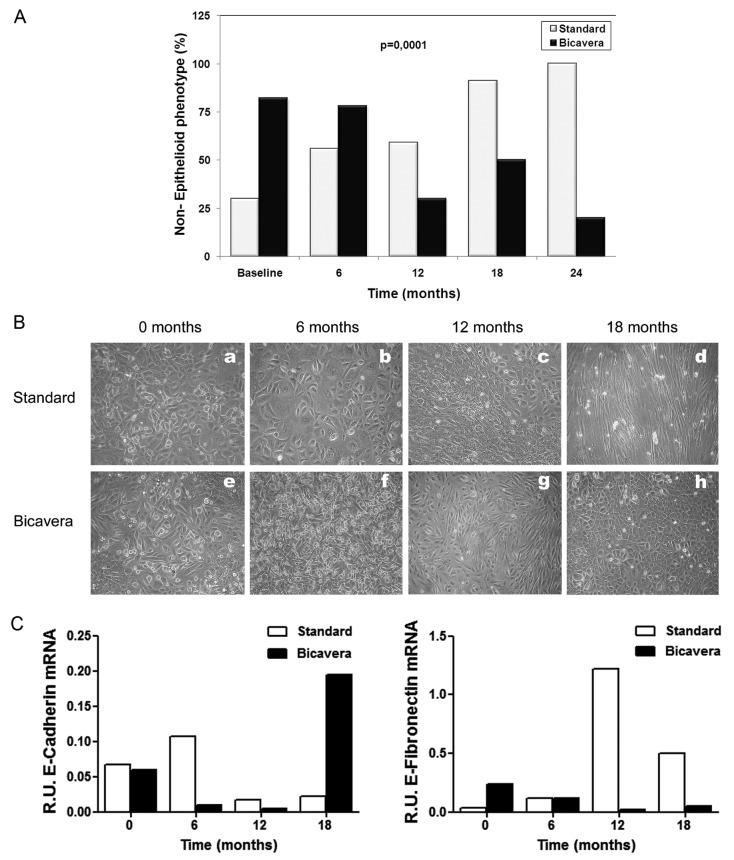

Ex vivo MC cultures from the BicaVera group showed a trend to gain and maintain the epithelial phenotype and a lower level of IL-8 expression. The BicaVera group showed an unexpected higher prevalence of the non-epithelioid phenotype at baseline (72% vs 30% in the standard group). However, the groups behaved differently at the medium- and long-term, showing a trend in patients on standard fluid to gain the non-epithelioid phenotype, compared with a clear and significant loss of the non-epithelioid phenotype in the BicaVera group. At 24 months, all patients in the standard-fluid group had gained the non-epithelial phenotype, but only 20% of patients of the BicaVera group showed that phenotype. The overall differences between the groups were statistically significant by linear mixed-model analysis for both fluid and time [fluid–time intersection, p = 0.0001, Figure 3(A)]. Figure 3(B,C) shows representative examples involving 2 patients—1 on standard fluid, and 1 on BicaVera—showing the acquisition of the non-epithelioid morphology and increased expression of fibronectin in the patient on standard fluid, and preservation of the epithelioid morphology and increased expression of E-cadherin in the patient on BicaVera at 18 months’ follow-up.

Figure 3.

— Epithelioid and non-epithelioid mesothelial cell (MC) phenotypes in the standard fluid and BicaVera (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) study groups. (A) Differences in the percentage of non-epithelioid MC phenotypes in the groups over time (mixed model, fluid–time: p = 0.0001). (B,C) Representative images from 2 patients (a – d = standard fluid; e – h = BicaVera) showing acquisition of non-epithelioid MC morphology and increased expression of fibronectin with standard fluid and preservation of epithelioid MC morphology and increased expression of E-cadherin with BicaVera fluid at 18 months of follow-up. R.U. = relative units.

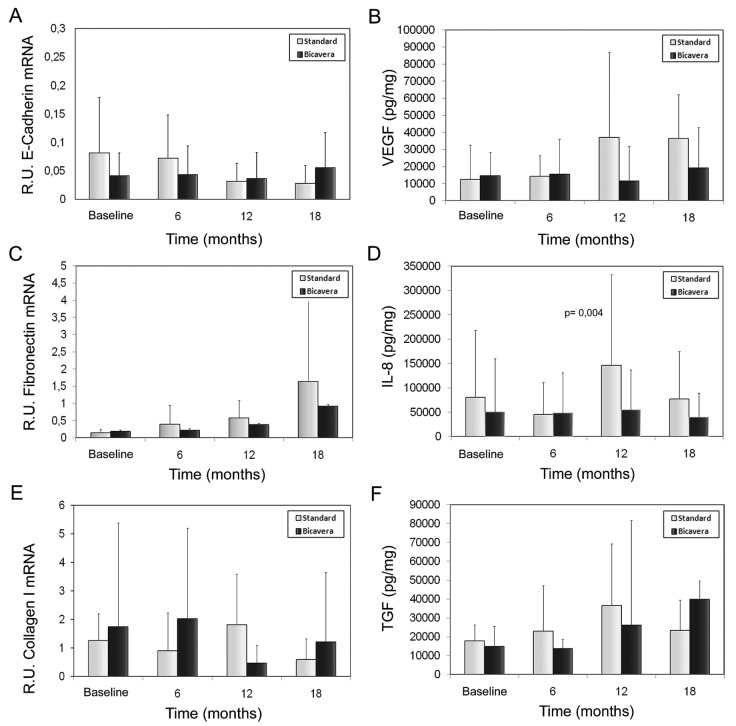

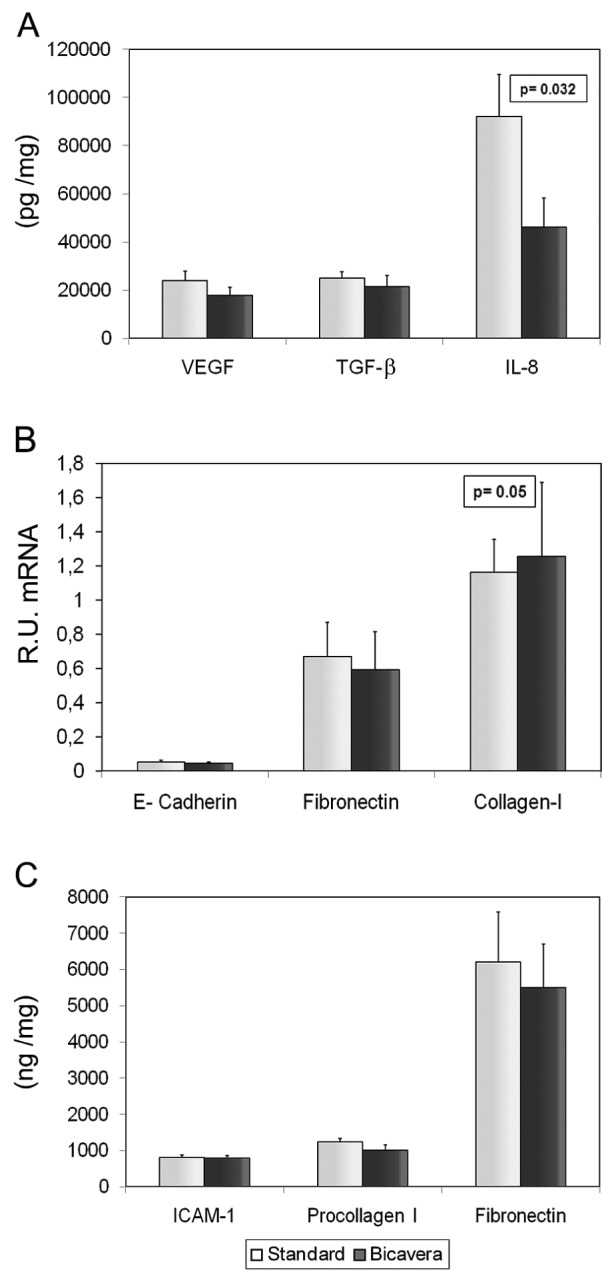

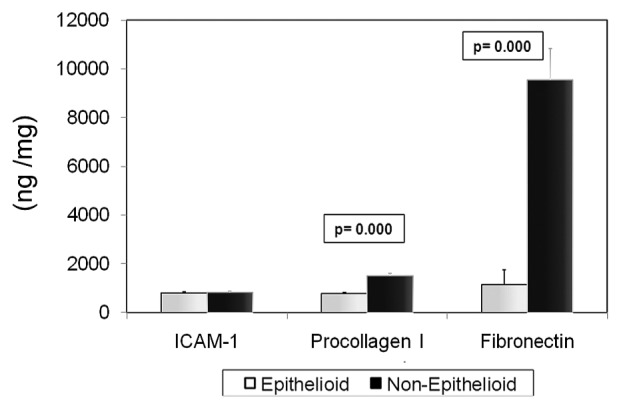

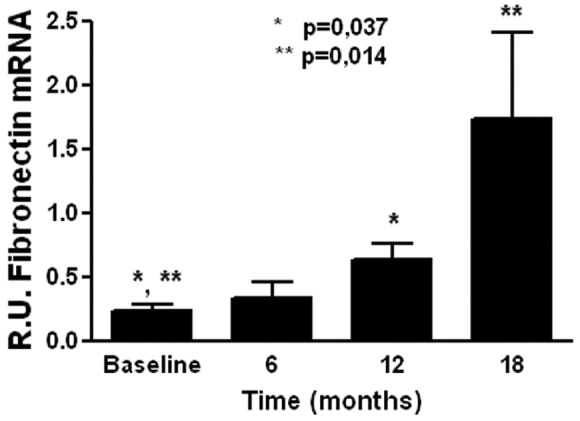

Figure 4(A–F) shows the levels of EMT-associated molecules (E-cadherin, fibronectin, collagen I, VEGF, IL-8, and TGF-β) in supernatant or cellular extract from effluent-derived MCs, together with the linear mixed-model analysis. Only the IL-8 level was significant lower in the BicaVera group (p < 0.004) than in the standard group. Those data were confirmed when all samples were evaluated according to fluid group only [Figure 5(A,C)]. Studies in cellular lysate [Figure 5(C)] did not show significant differences by fluid group for intracellular adhesion molecule 1, procollagen, and fibronectin. Non-epithelioid MCs showed higher levels of procollagen and fibronectin (p = 0.0001, Figure 6).

Figure 4.

— Bar plots of cytokine levels in supernatant or extract from mesothelial cells (MCs) derived from effluents in the BicaVera (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) and standard fluid (Stay·Safe: Fresenius Medical Care) groups. The statistical comparison uses mixed-model analysis, which determines the significance of differences between the groups and for each group over time. No significant differences were observed for (A) levels of E-cadherin messenger RNA (mRNA) in MCs (relative units); (B) production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, picograms per milligram) in supernatant; (C) levels of fibronectin mRNA in MCs (relative units); (E) levels of collagen I mRNA in MCs (relative units); and (F) levels of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1, picograms per milligram) in supernatant. Significantly higher levels were observed only for (D) supernatant levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8, picograms per milligram) in the standard fluid group, which showed a significant trend to rise over time (fluid–time: p < 0.01). R.U. = relative units.

Figure 5.

— Mean values of the various mesothelial cell products in culture for the study groups (all samples). We observed (A) significantly higher levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8, picograms per milligram) in supernatant in the standard fluid group; (A,B) similar levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), E-cadherin, fibronectin, and collagen I in both groups; and (C) no significant differences in protein levels (nanograms per milligram) of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), procollagen I, and fibronectin in MC lysate. BicaVera: solution from Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany. R.U. = relative units.

Figure 6.

— In a comparison of cellular lysates by mesothelial cell phenotype, protein levels (nanogram per milligram) of procollagen and fibronectin were observed to be higher (p = 0.0001) for the non-epithelioid phenotype; levels of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) were observed to be similar for all phenotypes.

Because non-epithelioid MCs appeared in effluent in the early and late PD periods in the BicaVera group, we studied molecules associated with EMT from cells at different stages of PD, using analysis of variance to compare results obtained at baseline and after 18 months on PD. The non-epithelioid cells initially observed in the BicaVera group were characterized by lower levels of fibronectin mRNA than were seen with non-epithelioid cells from the BicaVera group at 18 months (0.23 ± 0.2 relative units vs 1.72 ± 2.54 relative units, p = 0.05, Figure 7).

Figure 7.

— Expression levels of fibronectin messenger RNA (mRNA) in non-epithelioid mesothelial cells (MCs) from the BicaVera (Fresenius Medical Care, Bad Homburg, Germany) group. Non-epithelioid MCs appear to be associated with levels of fibronectin mRNA that, compared with baseline, are higher at later periods. R.U. = relative units.

INFLUENCE OF PERITONITIS EPISODES ON VARIABLES RELATED TO EMT

The numbers of patients and of peritonitis episodes were small, and so drawing definitive conclusions is impossible. The levels of cytokines and growth factors in supernatants or MC extracts in patients without peritonitis were similar to those in the whole group. The percentage of patients affected by peritonitis was similar in both groups: 9 episodes in the standard group, and 9 episodes in the BicaVera group. The global peritonitis incidence was slightly but nonsignificantly higher in the BicaVera group (1 episode in 25 patient–months vs 1 episode in 30 patient–months in the standard group). In the standard group, 4 patients showed non-epithelioid morphology pre-peritonitis; at the end of follow-up, 3 had maintained the same morphology, and 1 had changed to epithelioid morphology. In the BicaVera group, 3 patients showed non-epithelioid morphology, and 1 showed epithelioid morphology pre-peritonitis; all showed the epithelioid phenotype at the end of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of a bicarbonate/low-GDP PD fluid (BicaVera) on EMT of MCs in vitro and ex vivo. We defined EMT as the acquisition of a non-epithelioid phenotype, associated with loss of E-cadherin expression and production of higher amounts of mesenchymal products. Although specific studies on the correlation between ex vivo and in vivo methods for accurately diagnosing EMT in the peritoneal membrane are lacking, our data, repeated in multiple studies of PD patients, published and unpublished, continue to demonstrate consistency in findings with both approaches. We hypothesize that, when a patient shows repetitively epithelioid or non-epithelioid phenotype ex vivo, the findings from a peritoneal biopsy in the same patient show good correlation. Our data from the analysis of in vitro and ex vivo exposure of MCs to a bicarbonate/low-GDP fluid are consistently associated with preservation or acquisition of a MC epithelioid phenotype, which contrasts with the trend of MCs to acquire an EMT-associated non-epithelioid status with the use of standard fluid.

In vitro cell cultures of omentum-derived MCs preserve a physiologic phenotype. By contrast, if standard fluid with a high content of GDPs is added to cultures, a non-epithelioid phenotype associated with the loss of E-cadherin expression develops. Compared with cells treated with TGF-β1, cells exposed to standard fluid show this effect on E-cadherin at a later time point (72 hours), indicating that accumulation of a soluble factor or factors is required to repress expression of that epithelial marker. In this context, we previously described induction of TGF-β1 expression with exposure of omentum-derived MCs to standard PD fluids (22), a situation that in turn may induce EMT. By contrast, we showed that the addition of BicaVera (and other low-GDP fluids) to MC cultures barely affects epithelioid morphology and expression of E-cadherin in the cultured cells, revealing preservation of the original physiologic MC identity (18). The foregoing results demonstrate that the GDP content of PD fluids has an important role in the induction of EMT in MCs.

The analysis of EMT markers confirms that non-epithelioid cells show higher levels of VEGF, fibronectin, and collagen I, and reduced levels of E-cadherin, reflecting good consistency between morphology and molecular markers of EMT. However, when we analyzed markers of EMT in ex vivo studies in both groups of patients, no conclusive results were observed with respect to EMT-associated molecules, including fibronectin and TGF-β1. Only the level of IL-8 expression was significantly higher in cells from the standard-fluid group. Levels of IL-8 have been shown to be induced in MCs in vitro by standard PD fluids (23) and by GDPs (24). Furthermore, there are hints that IL-8 might influence solute transport in PD-related peritonitis and that IL-8 promotes cell migration (25), thereby exacerbating deterioration of the peritoneal membrane. The finding of higher levels of the chemokine IL-8 could point to a pro-inflammatory state in the standard-fluid group.

The foregoing results are tempered by the unexpected appearance at baseline of a higher percentage of patients showing a non-epithelioid phenotype in the BicaVera group. However, despite that initial finding, MCs chronically exposed to BicaVera showed an acquired positive change toward an epithelioid phenotype. By contrast, patients in the standard-fluid group showed a gradual transformation towards a generally non-epithelioid phenotype. Those data suggest that BicaVera fluid protects MCs by encouraging the maintenance of an epithelioid phenotype over the long term. Kalluri and Weinberg (26) described an intermediate state of EMT that is engaged during reparative processes and organ fibrosis. The non-epithelioid MCs initially observed in the BicaVera group might correspond to that intermediate stage of EMT (“type 1”) and represent an initial reparative process. The phenomenon of EMT is an adaptive and reparative physiologic phenomenon; it becomes pathological when processes that induce EMT are maintained over time and are not properly regulated. Compared with the non-epithelioid cells from the BicaVera group at 18 months, the non-epithelioid MCs initially observed in the BicaVera group were characterized by lower levels of fibronectin mRNA. That difference over time could represent different functional stages of a common morphology: early reparative non-epithelioid cells compared with late profibrotic non-epithelioid cells.

The development of EMT could be promoted by episodes of peritonitis. We therefore compared EMT markers in MCs from patients with and without peritonitis, finding no significant differences. The most remarkable finding in patients treated with BicaVera who experienced peritonitis was the persistent preservation of the epithelioid phenotype over time. We consider that preservation of the mesothelial phenotype should be beneficial for patients, although we would need tissue samples to confirm that hypothesis.

In agreement with our results, a recent report showed that various GDPs present in standard PD fluids can induce EMT of MCs in vitro and that low-GDP fluids have less impact on peritoneal fibrosis and EMT in vivo in a rat model (27). All of those results accord with results obtained in several patient series, including the present report (16,17). Mechanistically, the induction of EMT by standard fluid is related to high GDP content in such fluid, which may contribute to AGE accumulation, activation of RAGE, and damage to MCs (14,15,28). The specificity of BicaVera, with its bicarbonate instead of the usual lactate buffer, relative to effects on EMT of MCs requires further studies with larger samples than that in the present report.

Our study confirms previous data on the decreased UF capacity and increased transport of small solutes associated with more biocompatible fluids. There is no definitive explanation for those observations, although several authors have speculated that the less biocompatible fluids induce an increase in capillary permeability by increasing the response to molecules such as VEGF.

The most important limitations of our study are its nonrandomized nature and the low number of patients at final evaluation. Although a random selection cannot be equal to a randomization procedure, the characteristics of the patients included in each group were quite similar except for the larger number of patients with diabetes and higher initial RRF in the BicaVera group. In the pre-PD peritoneum, patients with diabetes showed a significant decrease in lumen-to-vessel diameter ratio compared with the ratio in nondiabetic patients. Uremia and diabetes have a significant impact on the pathogenesis of peritoneal sclerosis in the pre-PD peritoneum (29). The higher percentage of patients with diabetes in the group treated with BicaVera might penalize that group. However, the BicaVera group showed progressive phenotypic change and, at follow-up, mostly an epithelioid phenotype, which might suggest a protective role of BicaVera fluid—or at least inhibition of EMT of MCs.

CONCLUSIONS

We showed that, compared with MCs obtained from patients using standard fluid, MCs obtained from effluent of patients treated with the bicarbonate/low-GDP fluid BicaVera can acquire an epithelioid phenotype at medium term, despite the potential deleterious effect of peritonitis. We also observed favorable differences and outcomes for the bicarbonate/low-GDP fluid with respect to other EMT-associated molecules, although with no conclusive results. A larger series of patients might be required to confirm these results, but the consistency of our findings with those from other studies supports the hypothesis of an improvement in biocompatibility.

DISCLOSURES

This study was supported by grant 09/00641 to RS, from REDinREN (RETICS from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Red 06/0016, FEDER Funds) and by grant SAF 2007-61201 to MLC. The study was also partially supported by an unrestricted grant from Fresenius Medical Care. No other conflicts of interest have been declared by the remaining authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Marta Ramirez, Guadalupe González, and Jesus Loureiro from the experimental department of the hospital for their participation and comments; to Dr. José Jiménez–Heffernan, our pathologist; and to Rosario Madero for her statistical counsel and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Grassmann A, Gioberge S, Moeller S, Brown G. ESRD patients in 2004: global overview of patients numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20:2587–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krediet RT, Zweers MM, van der Wal AC, Struijk DG. Neoangiogenesis in the peritoneal membrane. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20(Suppl 2):S19–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krediet RT, Lindholm B, Rippe B. Pathophysiology of peritoneal membrane failure. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20(Suppl 4):S22–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jiménez–Heffernan JA, Perna C, Auxiliadora Bajo M, Luz Picazo M, Del Peso G, Aroeira L, et al. Tissue distribution of hyalinizing vasculopathy lesions in peritoneal dialysis patients: an autopsy study. Pathol Res Pract 2008; 204:563–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Margetts PJ, Bonniaud P. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit Dial Int 2003; 23:530–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams JD, Craig KJ, Topley N, Von Ruhland C, Fallon M, Newman GR, et al. Morphologic changes in the peritoneal membrane of patients with renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13:470–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aroeira LS, Aguilera A, Selgas R, Ramírez–Huesca M, Pérez–Lozano ML, Cirugeda A, et al. Mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells as a mechanism responsible for high solute transport rate in peritoneal dialysis: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 46:938–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yáñez–Mó M, Lara–Pezzi E, Selgas R, Ramírez–Huesca M, Domínguez–Jiménez C, Jiménez–Heffernan JA, et al. Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:403–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aroeira LS, Lara–Pezzi E, Loureiro J, Aguilera A, Ramírez–Huesca M, González–Mateo G, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates dialysate-induced alterations of the peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20:582–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Del Peso G, Jiménez–Heffernan JA, Bajo MA, Aroeira LS, Aguilera A, Fernández–Perpén A, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells is an early event during peritoneal dialysis and is associated with high peritoneal transport. Kidney Int Suppl 2008; (108):S26–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grossin N, Wautier MP, Wautier JL, Gane P, Taamma R, Boulanger E. Improved in vitro biocompatibility of bicarbonate buffered peritoneal dialysis fluid. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:664–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mortier S, De Vriese AS, McLoughlin RM, Topley N, Schaub TP, Passlick–Deetjen J, et al. Effects of conventional and new peritoneal dialysis fluids on leukocyte recruitment in the rat peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14:1296–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mortier S, Faict D, Gericke M, Lameire N, De Vriese A. Effects of new peritoneal dialysis solutions on leukocyte recruitment in the rat peritoneal membrane. Nephron Exp Nephrol 2005; 101:e139–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tauer A, Zhang X, Schaub TP, Zimmeck T, Niwa T, Passlick–Deetjen J, et al. Formation of advanced glycation end products during CAPD. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 41(Suppl 1):S57–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Vriese AS, Tilton RG, Mortier S, Lameire NH. Myofibroblast transdifferentiation of mesothelial cells is mediated by RAGE and contributes to peritoneal fibrosis in uraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21:2549–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Do JY, Kim YL, Park JW, Cho KH, Kim TW, Yoon KW, et al. The effect of low-glucose degradation product dialysis solution on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(Suppl 3):S22–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Do JY, Kim YL, Park JW, Chang KA, Lee SH, Ryu DH, et al. The association between the vascular endothelial growth factor–to–cancer antigen 125 ratio in peritoneal dialysis effluent and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28(Suppl 3):S101–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bajo MA, Pérez–Lozano ML, Albar–Vizcaino P, del Peso G, Castro MJ, Gonzalez–Mateo G, et al. Low-GDP peritoneal dialysis fluid (“Balance”) has less impact in vitro and ex vivo on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells than a standard fluid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26:282–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sansone G, Cirugeda A, Bajo MA, del Peso G, Sánchez Tomero JA, Alegre L, et al. Clinical practice protocol update in peritoneal dialysis-2004 (Spanish). Nefrologia 2004; 24:410–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Selgas R, Fernandez–Reyes MJ, Bosque E, Bajo MA, Borrego F, Jimenez C, et al. Functional longevity of the human peritoneum: how long is continuous peritoneal dialysis possible? Results of a prospective medium long-term study. Am J Kidney Dis 1994; 23:64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. López–Cabrera M, Aguilera A, Aroeira LS, Ramírez–Huesca M, Pérez–Lozano ML, Jiménez–Heffernan JA, et al. Ex vivo analysis of dialysis effluent–derived mesothelial cells as an approach to unveiling the mechanism of peritoneal membrane failure. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:26–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loureiro J, Schilte M, Aguilera A, Albar–Vizcaíno P, Ramírez–Huesca M, Pérez–Lozano ML, et al. BMP-7 blocks mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells and prevents peritoneal damage induced by dialysis fluid exposure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1098–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bender TO, Riesenhuber A, Endemann M, Herkner K, Witowski J, Jörres A, et al. Correlation between HSP-72 expression and IL-8 secretion in human mesothelial cells. Int J Artif Organs 2007; 30:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welten AG, Schalkwijk CG, ter Wee PM, Meijer S, van den Born J, Beelen RJ. Single exposure of mesothelial cells to glucose degradation products (GDPs) yields early advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and a proinflammatory response. Perit Dial Int 2003; 23:213–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bates RC, DeLeo MJ, 3rd, Mercurio AM. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colon carcinoma involves expression of IL-8 and CXCR-1–mediated chemotaxis. Exp Cell Res 2004; 299:315–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:1420–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Oh EJ, Ryu HM, Choi SY, Yook JM, Kim CD, Park SH, et al. Impact of low glucose degradation product bicarbonate/lactate–buffered dialysis solution on the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of peritoneum. Am J Nephrol 2010; 31:58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Witowski J, Wisniewska J, Korybalska K, Bender TO, Breborowicz A, Gahl GM, et al. Prolonged exposure to glucose degradation products impairs viability and function of human peritoneal mesothelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12:2434–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Honda K, Hamada C, Nakayama M, Miyazaki M, Sherif AM, Harada T, et al. Impact of uremia, diabetes, and peritoneal dialysis itself on the pathogenesis of peritoneal sclerosis: a quantitative study of peritoneal membrane morphology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 3:720–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]