Abstract

The entry of metastatic cancer cells into the liver can trigger a rapid inflammatory response with increased local production of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα). We investigated the molecular mechanisms that protect tumor cells from TNFα-induced apoptosis. A molecular crosstalk between the TNFα/TNFR/NFκB and IGF-IR/PI3-K/AKT pathways was identified that leads to autocrine IL-6/IL-6R/STAT3 signaling, rendering tumor cells resistant to cell death and enabling the metastatic colonization of the liver.

Keywords: TNF, IGF, IL-6, liver metastasis, inflammation, apoptosis, survival, STAT3

Inflammation has long been recognized as a “double-edged sword” in cancer initiation and progression.1 Tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), the cytokine that orchestrates the inflammatory response, can have multiple and diametrically opposing effects on tumor cell survival and the progression of malignant disease.2 While the involvement of this and other cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), in the etiology of primary colon cancer has been well documented,3 much less is known about their roles during the progression of metastatic disease, particularly in the liver.

The liver is a site of metastasis for several malignancies including cancers of the gastrointestincal tract, in particular colorectal cancer. The liver is a vital organ and the extent of its involvement with metastatic disease is therefore a major determinant of survival. Metastatic cells arriving in the liver can trigger an inflammatory response that entails release of multiple cytokines including TNFα, which is pro-apoptotic at high concentrations. In trying to understand how tumor cells withstand this apoptotic insult and survive to flourish and produce metastases in such an inflammatory microenvironment, we analyzed the response of highly metastatic lung and colon cancer cells to increasing TNFα concentrations in vitro. We found that these cells, but not poorly metastatic counterparts, can be rescued from apoptosis in the presence of high TNFα concentrations, due to a marked increase in IL-6 production that ensues the TNFα-induced activation of NFκB.4

IL-6 belongs to a family of cytokines that operate through receptor complexes containing the signal transducer gp130 (CD130). The binding of IL-6 to its cellular receptor IL-6Rα (CD126) or a soluble form of this receptor (sIL-6R) leads to the recruitment of gp130 and results in Janus kinase (JAK) activation and the phosphorylation of transcription factors of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family, particularly STAT3. Phosphorylated STAT3 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where—upon DNA binding—it transactivates various genes, including oncogenes as well as genes coding for cell survival and cell cycle regulators, cytokines and mediators of angiogenesis and metastasis.5

In our highly metastatic cells, we found that increased IL-6 production in response to TNFα induced an autocrine gp130- and IL-6R–dependent activation of STAT3, inhibiting caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. The preferential transcriptional activation of IL-6 by TNFα was Type I insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR)-dependent, and could be further enhanced when cells were co-stimulated with TNFα and IGF-I. Moreover, while the ligand-induced activation of IGF-IR did not, in itself, significantly increase STAT3 activation and IL-6 production, activated IGF-IR could act synergistically with a TNFα-initiated signaling cascade to produce increased IL-6 levels. This effect was RelA/p65 and PI3-K signaling-dependent, because it was inhibited when p65 translocation or AKT activation were blocked. Furthermore, such an IL-6-mediated survival mechanism was critical for the metastatic colonization of the liver, as the silencing of either IL-6 or gp130 by siRNA and the consequent abrogation of the pro-survival effect of TNFα inhibited the formation of liver metastases by colon and lung carcinoma cells.4

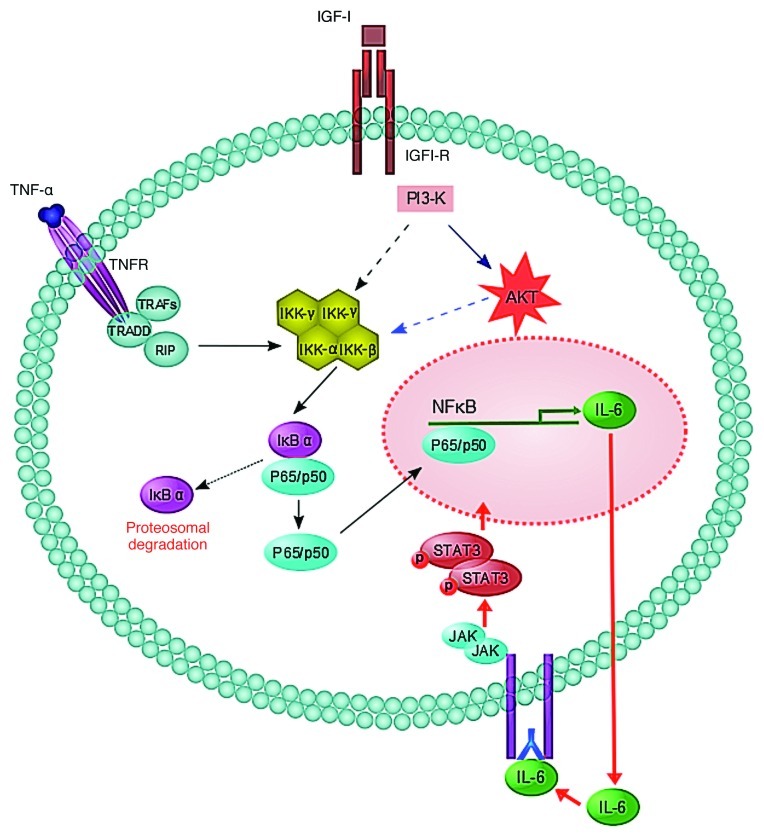

These results identify a novel crosstalk mechanism that links inflammatory, NFκB-mediated and growth factor-initiated AKT signaling and provides an escape route from inflammation-induced apoptosis that is required for the formation of hepatic metastases (Fig. 1). We and others have already shown that TNFα is implicated in the induction of endothelial cell adhesion receptors and hence in the trans-endothelial migration and extravasation of tumor cells.6 The present study adds another layer of complexity to the role of TNFα in liver metastasis by showing that, at least in some settings, TNFα can play a dual metastasis-promoting role, as a modifier of the hepatic microenvironment and as a promoter of tumor cell survival.

Figure 1. A schematic model for proposed crosstalk between the IGF-IR and TNFR signaling pathways leading to IL-6/IL-6R/STAT3 survival signaling. IκB, inhibitor of NF-κB; IKK, IκB kinase; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; TRADD, TNFR-associated death domain; TRAF, TNFR associated factor. For a recent review on TNFR signaling, please see reference 10. Drs. Shun Li and Naseer Qayum contributed to the design of Figure 1.

Our results add to the growing body of evidence that has collectively linked IL-6 to the development and progression of cancer. Elevated serum IL-6 levels have been reported in patients affected by various malignancies, and shown to correlate with poor clinical outcome.7 Moreover, IL-6 has been identified as a cell survival and proliferation factor in cancers such as multiple myeloma and prostate carcinoma. In some tumors, including breast, prostate and colon cancer, this activity can be mediated by an autocrine circuitry, while in others, IL-6 provided by the tumor microenvironment operates in a paracrine fashion. This was shown in multiple myeloma and neuroblastoma cells that express IL-6 receptors and utilize bone marrow mesenchymal cell-derived IL-6 for proliferation.8 IL-6 has also been identified as a paracrine survival factor in the liver, acting on both primary hepatocellular carcinoma and metastases.4 Our data add to these results by showing that, in the presence of pro-inflammatory stimuli, tumor cells can activate an IL-6-dependent autocrine survival mechanism, allowing them to persist and grow in the hepatic microenvironment.

As the use of IL-6- and IL-6R-targeting antibodies for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and colitis, has become a clinical reality,9 our studies provide a compelling rational for the utilization of anti-inflammatory drugs that target the IL-6/IL-6R axis for the prevention of liver metastatic disease.9

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/21424

References

- 1.Germano G, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Cytokines as a key component of cancer-related inflammation. Cytokine. 2008;43:374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balkwill F. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:361–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmadi A, Polyak S, Draganov PV. Colorectal cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: the search continues. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:61–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Wang N, Brodt P. Metastatic cells can escape the proapoptotic effects of TNF-α through increased autocrine IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. 2012;72:865–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose-John S, Scheller J, Elson G, Jones SA. Interleukin-6 biology is coordinated by membrane-bound and soluble receptors: role in inflammation and cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:227–36. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auguste P, Fallavollita L, Wang N, Burnier J, Bikfalvi A, Brodt P. The host inflammatory response promotes liver metastasis by increasing tumor cell arrest and extravasation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1781–92. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihara M, Hashizume M, Yoshida H, Suzuki M, Shiina M. IL-6/IL-6 receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122:143–59. doi: 10.1042/CS20110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ara T, Declerck YA. Interleukin-6 in bone metastasis and cancer progression. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sansone P, Bromberg J. Targeting the interleukin-6/Jak/stat pathway in human malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1005–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schröfelbauer B, Hoffmann A. How do pleiotropic kinase hubs mediate specific signaling by TNFR superfamily members? Immunol Rev. 2011;244:29–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]