Abstract

Biological systems involving short-range activators and long-range inhibitors can generate complex patterns. Reaction-diffusion models postulate that differences in signaling range are caused by differential diffusivity of inhibitor and activator. Other models suggest that differential clearance underlies different signaling ranges. To test these models, we measured the biophysical properties of the Nodal/Lefty activator/inhibitor system during zebrafish embryogenesis. Analysis of Nodal and Lefty gradients reveals that Nodals have a shorter range than Lefty proteins. Pulse-labelinganalysis indicates that Nodals and Leftys have similar clearance kinetics, whereas fluorescence recovery assays reveal that Leftys have a higher effective diffusion coefficient than Nodals. These results indicate that differential diffusivity is the major determinant of the differences in Nodal/Lefty range and provide biophysical support for reaction-diffusion models of activator/inhibitor-mediated patterning.

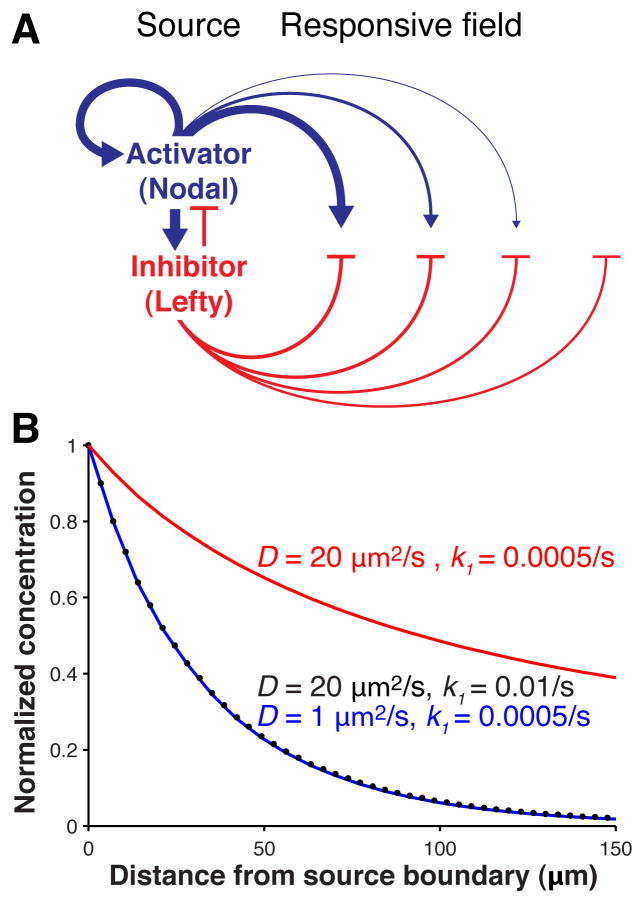

In 1952, Alan Turing put forward the reaction-diffusion model in which two interacting and diffusing molecules can generate complex patterns (1). Gierer and Meinhardt postulated that pattern formation in reaction-diffusion models requires a short-range activator that enhances both its own production and that of a long-range inhibitor (2) (Fig. 1A). Despite the prominence of reaction-diffusion models and the widespread occurrence of short-range activators and long-range inhibitors in development (3–10), it is unclear how differences in activator and inhibitor ranges arise in vivo. The classic reaction-diffusion models postulate that the inhibitor is more diffusive than the activator (Text S1), but more recent studies suggest that differential signal clearance might be a major determinant of differences in signaling range (11–18) (Fig. 1B). This question has not been resolved because the biophysical properties of diffusion and clearance have not been measured for any activator/inhibitor pair.

Fig. 1. Model of the Nodal/Lefty activator/inhibitor reaction-diffusion system and regulation of range.

(A) In the source, Nodal signals (blue) activate their own expression as well as the expression of Lefty (red), which inhibits Nodal production. Nodal signaling in the responsive field is inhibited by the long-range inhibitor Lefty. (B) Distribution is controlled by both diffusivity, D, and clearance, k1. Highly mobile molecules that are rapidly cleared from the extracellular space (black circles) can form gradients similar to those formed by poorly diffusive molecules that are slowly cleared (blue). Decreasing the clearance of the more diffusive species results in a long-range gradient (red). Simulations were performed as described in Text S7.

The TGF-β signals Nodal and Lefty constitute an activator/inhibitor-based system in animals ranging from sea urchin to mouse (3–5, 16, 18–22) (Text S2). Nodals activate signaling during mesendoderm induction and left-right patterning, whereas Leftys block pathway activation. The Nodal/Lefty system fulfills two of the tenets of activator/inhibitor reaction-diffusion models: (i) Nodals are short- to mid-range activators that enhance their own expression, and (ii) Leftys are long-range inhibitors that are activated by Nodals (3–5, 19, 22). Genetic and embryological studies in zebrafish have shown that during mesendoderm induction, the two Nodal signals Cyclops and Squint and the two Nodal signaling inhibitors Lefty1 and Lefty2 have different activity ranges: Cyclops is a short-range activator of mesendodermal gene expression, Squint acts at a medium range, and Lefty1 and Lefty2 are long-range inhibitors (6, 23). Moreover, these Nodal signals induce their own expression as well as the expression of Leftys (5, 19, 22) (Fig. 1A). However, the biophysical properties that control the different activity ranges of Nodals and Leftys are unknown. It therefore remains unclear whether one of the central tenets of reaction-diffusion models - differential diffusivity of activator and inhibitor - is fulfilled in vivo (4–6, 15–16, 19, 22, 24). To address this question, we performed measurements of Nodal and Lefty distribution, clearance, and diffusivity during zebrafish embryogenesis.

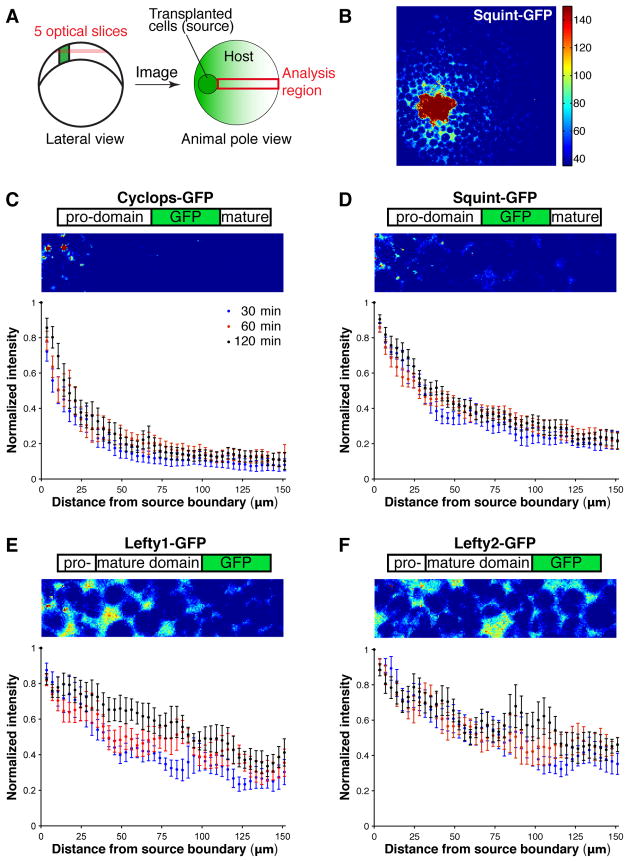

To visualize Nodal and Lefty proteins in vivo, we generated active fusions of green fluorescent protein (GFP) with Cyclops, Squint, Lefty1, and Lefty2 (see figs. S2–S11, Text S3, and Text S4 for analyses of fusion protein activity, processing, localization, and distribution). When expressed from a localized source in blastula embryos, the fusion proteins had similar activity ranges as their untagged counterparts (fig. S5, fig. S10). In vivo imaging revealed that the distribution profiles of the fusion proteins reflected their activity ranges: the gradient formed by Cyclops-GFP exhibited a punctate distribution and dropped steeply as the distance from the source increased, whereas the gradient formed by Squint-GFP was more diffuse and reached farther (Fig. 2C and 2D). The distributions of Lefty1- and Lefty2-GFP were more shallow, and long-range and super-long-range, respectively (Fig. 2E and 2F).

Fig. 2. Measurement of Nodal- and Lefty-GFP distributions.

(A) At late blastula stages, approximately 40 cells secreting Nodal- or Lefty-GFP proteins were transplanted from donor embryos into wildtype hosts (Text S4). The gradient profile was determined using a maximum intensity projection of five confocal slices encompassing a depth of 20 μm (about one cell). (B) A representative projection is shown for Squint-GFP. (C–F) Construct schematic, representative maximum intensity projection and distribution profiles 30, 60 and 120 min post transplantation for Cyclops-GFP (C), Squint-GFP (D), Lefty1-GFP (E), and Lefty2-GFP (F). Embryos that did not undergo transplantation were used for background subtraction, and all intensities were normalized to the value most proximal to the source. Error bars indicate standard error. Number of embryos analyzed at 30, 60 and 120 min post transplantation, respectively, for Cyclops-GFP n30=7, n60=7, n120=7; for Squint-GFP n30=12, n60=17, n120=20; for Lefty1-GFP n30=8, n60=8, n120=13; for Lefty2-GFP n30=12, n60=10, n120=12.

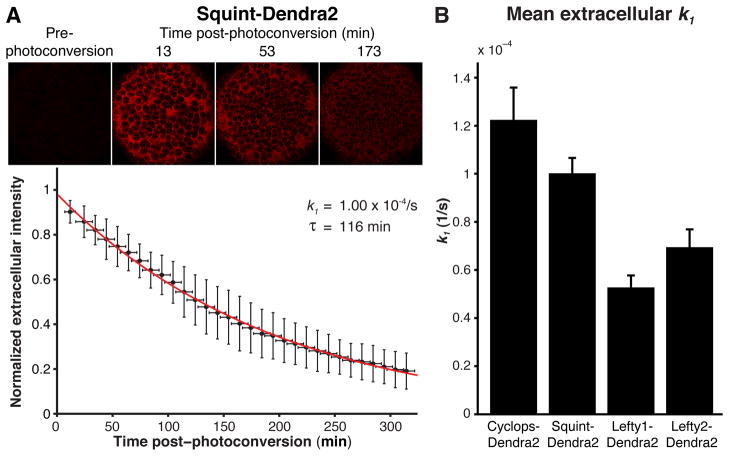

To determine whether differential clearance underlies the different ranges of Nodal and Lefty signals, we developed a pulse-labeling assay to measure extracellular clearance rate constants. We fused the monomeric green-to-red photoconvertible protein Dendra2 (25) to Nodals and Leftys and uniformly expressed these active fusions in blastula embryos (figs. S2–S10 and Text S3). We then switched the fluorescent state of Dendra2 from green to red throughout the embryo and monitored the decrease in intensity of the extracellular red signal for 300 min (Fig. 3, Movie S1). By fitting the data with an exponential decay model, we obtained clearance rate constants (k1) and calculated the inversely related extracellular half-lives, τ = ln(2)/k1 (see figs. S12–S16 and Text S5 for control experiments and detailed measurements). We found half-lives of 95 to 218 min with clearance rate constants of (1.22 ± 0.13) × 10−4/s for Cyclops-Dendra2, (1.00 ± 0.06) × 10−4/s for Squint-Dendra2, (0.53 ± 0.05) × 10−4/s for Lefty1-Dendra2, and (0.69 ± 0.07) × 10−4/s for Lefty2-Dendra2. Thus, protein half-lives increase only slightly as ranges increase, suggesting that differential clearance is only a minor contributor to the differences in Nodal and Lefty range.

Fig. 3. Measurement of extracellular clearance rate constants.

(A) Uniformly expressed Nodal- or Lefty-Dendra2 fusion proteins were photoconverted using a UV pulse. The average extracellular photoconverted Dendra2 intensity was monitored over time and used to determine the clearance rate constants (k1) and half-lives (τ = ln(2)/k1) by fitting exponential functions to data from individual embryos (Text S5). The normalized average intensity from 10 min interval Squint-Dendra2 experiments (black, n = 11) is shown fitted with an exponential function (red). Error bars indicate standard deviation. See fig. S12 for Cyclops-, Lefty1-, and Lefty2-Dendra2 results. (B) Summary of mean extracellular k1 values. Error bars indicate standard error.

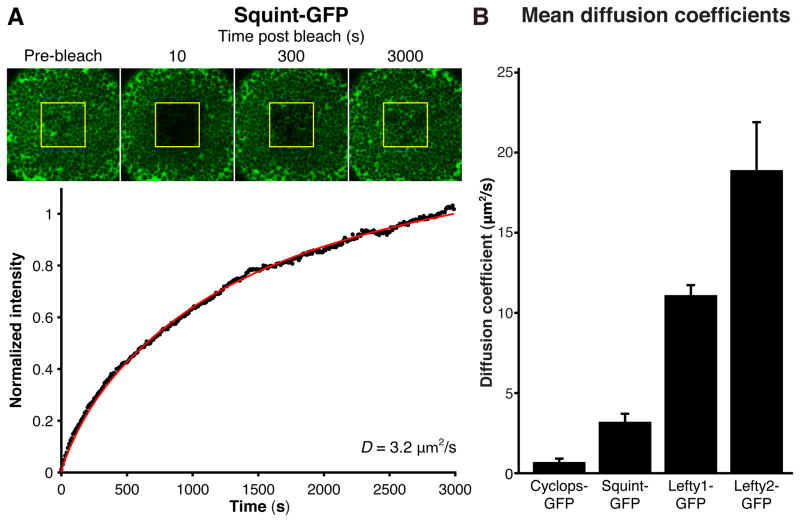

To determine whether differential diffusivity underlies the different ranges of Nodals and Leftys, we measured their effective diffusion coefficients using Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) (12–13, 18, 26). FRAP assays can measure diffusivity over developmentally relevant length- and time-scales by observing the diffusion-dependent re-appearance of fluorescence after photobleaching (Text S6). To perform FRAP assays, we ubiquitously expressed Nodal- and Lefty-GFP fusion proteins in blastula embryos and photobleached a cuboidal volume containing several hundred cells. We then monitored the recovery of fluorescence in the bleached region over a period of 50 min (3000 s) (Fig. 4A, figs. S18–S23). Photobleaching was nearly uniform (fig. S22), had no apparent toxic effects on the embryo, and fluorescence recovery occurred from regions adjacent to the bleached window (fig. S23). We found that it was crucial to account for the three-dimensional geometry of the embryo (Text S6, fig. S19) and thus determined the effective diffusion coefficients of the fusion proteins by fitting a three-dimensional diffusion model to recovery profiles. We obtained effective diffusion coefficients of 0.7 ± 0.2 μm2/s for Cyclops-GFP, 3.2 ± 0.5 μm2/s for Squint-GFP, 11.1 ± 0.6 μm2/s for Lefty1-GFP, and 18.9 ± 3.0 μm2/s for Lefty2-GFP (Fig. 4B, figs. S18-S23 and Text S6). Thus, increased protein diffusivities reflect increased ranges, indicating that differential diffusivity is a major contributor to the differences in Nodal and Lefty range.

Fig. 4. Measurement of effective diffusion coefficients.

(A) Uniformly expressed Nodal- or Lefty-GFP fusion proteins were locally photobleached (yellow box) at blastula stages. Fluorescence recovery was monitored over time, and the effective diffusion coefficient, D, was determined by fitting the resulting recovery profile (black) with simulated recovery curves (red) that were numerically generated using a model that includes diffusion, production and clearance in a three-dimensional embryo-like geometry (Text S6). Results for an individual Squint-GFP embryo are shown. See fig. S18 for Cyclops-, Lefty1-, and Lefty2-GFP results. (B) Summary of mean diffusion coefficients. Error bars indicate standard error.

To test whether the experimentally determined values for diffusivity and clearance accurately predict the measured distribution profiles, we numerically simulated signal secretion from a localized source, diffusion, and clearance (12, 14, 26) in a three-dimensional geometry appropriate for blastula embryos (Text S7). Using the measured values for diffusivity and clearance, these simulations yield distribution profiles similar to the experimentally determined protein distributions (fig. S26) and thus provide independent support for the validity of the experimental approaches.

Our results have two major implications. First, differential diffusivity underlies differences in activator/inhibitor range. The differences in range (Cyclops<Squint<Lefty1<Lefty2) are reflected in the differences in effective diffusion coefficients (Cyclops<Squint<Lefty1<Lefty2). There is a similar trend in half-lives, but the differences in diffusivity are much more pronounced than the differences in clearance. During embryogenesis, the sources of Nodal and Lefty overlap, but Nodal signaling is active near the source and inhibited by Lefty farther away. Our results suggest that the lower mobility of Nodal allows its accumulation close to the site of secretion, whereas the high mobility of Lefty leads to rapid long-range dispersal and prevents accumulation near the source. Thus, the differential diffusivity of Nodal and Lefty signals serves as the biophysical basis for the spatially restricted induction of cell fates during embryogenesis.

Second, the previously described network topology of the Nodal/Lefty system and the biophysical properties of Nodals and Leftys measured here support the activator/inhibitor reaction-diffusion model of morphogenesis: a less diffusive activator (Nodal) induces both its own production and that of a more diffusive inhibitor (Lefty) (3–4). The Nodal/Lefty reaction-diffusion system is further constrained by pre-patterns and rapid cell fate specification and thus results in graded pathway activation during mesendoderm induction and exclusive pathway activation on the left during left-right specification (see Text S2 for detailed discussion). Mathematical models have postulated that the inhibitor in reaction-diffusion systems must have a higher diffusion coefficient than the activator. Several models have postulated an at least six-fold difference between clearance-normalized inhibitor and activator diffusion coefficients; i.e. ℜ = (D/k1)inhibitor /(D/k1)activator > 6 (8, 16, 27–29). The average ratio of the normalized diffusivities of Leftys and Nodals measured here is ℜ ≈ 14, providing biophysical support for these modeling studies (see Text S8 for comparison of reaction-diffusion systems). The different diffusivities in the Nodal/Lefty biological system have counterparts in chemical reaction-diffusion systems. For example, patterns can be generated in a starch-loaded gel by combining an activator (iodide) with an inhibitor (chlorite) in the presence of malonic acid (30). In this in vitro system, diffusion of the activator is hindered by binding to the starch matrix and thought to result in a ~15-fold higher diffusivity of the inhibitor. These models and our measurements raise the possibility that differential binding interactions and a ratio of at least 5- to 15-fold of inhibitor and activator diffusivities might be a general feature of reaction-diffusion-based patterning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank X. Zhang for help with the cloning of Cyclops constructs, H. Othmer and A. Lander for helpful discussions, J. Dubrulle for discussions and primers for qRT-PCR, and S. Mango for comments on the manuscript. PM was supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization and the Human Frontier Science Program (HFSP). KWR is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. Our research was supported by grants from NIH (5RO1GM56211) and HFSP (RGP0066/2004-C).

References and Notes

- 1.Turing AM. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society of London series B. 1952:37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gierer A, Meinhardt H. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik. 1972;12:30. doi: 10.1007/BF00289234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondo S, Miura T. Reaction-diffusion model as a framework for understanding biological pattern formation. Science. 2010;329:1616. doi: 10.1126/science.1179047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinhardt H. Models for the generation and interpretation of gradients. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001362. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiratori H, Hamada H. The left-right axis in the mouse: from origin to morphology. Development. 2006;133:2095. doi: 10.1242/dev.02384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Schier AF. Lefty proteins are long-range inhibitors of Squint-mediated Nodal signaling. Curr Biol. 2002;12:2124. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein DE, Nappi VM, Reeves GT, Shvartsman SY, Lemmon MA. Argos inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor signalling by ligand sequestration. Nature. 2004;430:1040. doi: 10.1038/nature02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sick S, Reinker S, Timmer J, Schlake T. WNT and DKK determine hair follicle spacing through a reaction-diffusion mechanism. Science. 2006;314:1447. doi: 10.1126/science.1130088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-Zvi D, Shilo BZ, Fainsod A, Barkai N. Scaling of the BMP activation gradient in Xenopus embryos. Nature. 2008;453:1205. doi: 10.1038/nature07059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Economou AD, et al. Periodic stripe formation by a Turing mechanism operating at growth zones in the mammalian palate. Nat Genet. 2012;44:348. doi: 10.1038/ng.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller P, Schier AF. Extracellular movement of signaling molecules. Dev Cell. 2011;21:145. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kicheva A, et al. Kinetics of morphogen gradient formation. Science. 2007;315:521. doi: 10.1126/science.1135774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wartlick O, et al. Dynamics of Dpp signaling and proliferation control. Science. 2011;331:1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1200037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu SR, et al. Fgf8 morphogen gradient forms by a source-sink mechanism with freely diffusing molecules. Nature. 2009;461:533. doi: 10.1038/nature08391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Good JA, et al. Nodal stability determines signaling range. Curr Biol. 2005;15:31. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura T, et al. Generation of robust left-right asymmetry in the mouse embryo requires a self-enhancement and lateral-inhibition system. Dev Cell. 2006;11:495. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou S, et al. Free extracellular diffusion creates the Dpp morphogen gradient of the Drosophila wing disc. Curr Biol. 2012;22 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers KW, Schier AF. Morphogen gradients: from generation to interpretation. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2011;27:377. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schier AF. Nodal morphogens. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a003459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duboc V, Lapraz F, Besnardeau L, Lepage T. Lefty acts as an essential modulator of Nodal activity during sea urchin oral-aboral axis formation. Dev Biol. 2008;320:49. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grande C, Patel NH. Nodal signalling is involved in left-right asymmetry in snails. Nature. 2009;457:1007. doi: 10.1038/nature07603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen MM. Nodal signaling: developmental roles and regulation. Development. 2007;134:1023. doi: 10.1242/dev.000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Schier AF. The zebrafish Nodal signal Squint functions as a morphogen. Nature. 2001;411:607. doi: 10.1038/35079121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marjoram L, Wright C. Rapid differential transport of Nodal and Lefty on sulfated proteoglycan-rich extracellular matrix regulates left-right asymmetry in Xenopus. Development. 2011;138:475. doi: 10.1242/dev.056010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, et al. Method for real-time monitoring of protein degradation at the single cell level. Biotechniques. 2007;42:446. doi: 10.2144/000112453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregor T, Wieschaus EF, McGregor AP, Bialek W, Tank DW. Stability and nuclear dynamics of the Bicoid morphogen gradient. Cell. 2007;130:141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granero MI, Porati A, Zanacca D. A bifurcation analysis of pattern formation in a diffusion governed morphogenetic field. J Math Biol. 1977;4:21. doi: 10.1007/BF00276349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kondo S, Asai R. A reaction–diffusion wave on the skin of the marine angelfish Pomacanthus. Nature. 1995;376:765. doi: 10.1038/376765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamaguchi M, Yoshimoto E, Kondo S. Pattern regulation in the stripe of zebrafish suggests an underlying dynamic and autonomous mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607790104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lengyel I, Epstein IR. Modeling of Turing structures in the chlorite-iodide-malonic acid-starch reaction system. Science. 1991;251:650. doi: 10.1126/science.251.4994.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.