Abstract

Background: Rectovaginal fistulas are rare, and the majority is of traumatic origin. The most common causes are obstetric trauma, local infection, and rectal surgery. This guideline does not cover rectovaginal fistulas that are caused by chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was undertaken.

Results: Rectovaginal fistula is diagnosed on the basis of the patient history and the clinical examination. Other pathologies should be ruled out by endoscopy, endosonography or tomography. The assessment of sphincter function is valuable for surgical planning (potential simultaneous sphincter reconstruction).

Persistent rectovaginal fistulas generally require surgical treatment. Various surgical procedures have been described. The most common procedure involves a transrectal approach with endorectal suture. The transperineal approach is primarily used in case of simultaneous sphincter reconstruction. In recurrent fistulas. Closure can be achieved by the interposition of autologous tissue (Martius flap, gracilis muscle) or biologically degradable materials. In higher fistulas, abdominal approaches are used as well.

Stoma creation is more frequently required in rectovaginal fistulas than in anal fistulas. The decision regarding stoma creation should be primarily based on the extent of the local defect and the resulting burden on the patient.

Conclusion: In this clinical S3-Guideline, instructions for diagnosis and treatment of rectovaginal fistulas are described for the first time in Germany. Given the low evidence level, this guideline is to be considered of descriptive character only. Recommendations for diagnostics and treatment are primarily based the clinical experience of the guideline group and cannot be fully supported by the literature.

Keywords: rectovaginal fistula, surgery, incontinence, postpartal trauma, rectal cancer, German guideline

Abstract

Hintergrund: Rektovaginale Fisteln stellen eine seltene Erkrankung dar. Die Mehrzahl der rektovaginalen Fisteln ist traumatischer Genese. Die wichtigsten Ursachen stellen Entbindungstraumata, lokale Infektionen und Eingriffe am Rektum dar. Rektovaginale Fisteln bei chronisch-entzündlichen Darmerkrankungen werden in dieser Leitlinie nicht behandelt.

Methode: Es wurde ein systematisches Review der Literatur durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse: Die Diagnose einer rektovaginalen Fistel ergibt sich aus Anamnese und klinischer Untersuchung. Andere pathologische Veränderungen sollten durch Zusatzuntersuchungen (Endoskopie, Endosonographie, Schichtuntersuchung) ausgeschlossen werden. Eine Beurteilung der Sphinkterfunktion ist für die Planung des operativen Vorgehens (Frage der simultanen Sphinkterrekonstruktion) sinnvoll.

Eine persistierende rektovaginale Fistel kann in der Regel nur durch eine Operation zur Ausheilung gebracht werden. Es wurden verschiedene Operationsverfahren mit niedrigem Evidenzniveau beschrieben. Am häufigsten ist das transrektale Vorgehen mit endorektaler Naht. Der transperineale Zugang kommt in erster Linie bei simultaner Schließmuskelrekonstruktion zur Anwendung. Bei rezidivierenden Fisteln kann durch die Interposition von körpereigenem Gewebe (Martius-Lappen, M.gracilis) ein Verschluss erzielt werden. In neuen Studien wurde auch ein Verschluss durch Einbringen von Biomaterialien vorgestellt. Bei höher gelegenen Fisteln kommen auch abdominelle Verfahren zur Anwendung.

Häufiger als bei der Behandlung von Analfisteln ist bei der rektovaginalen Fistel eine Stomaanlage erforderlich. Je nach Ätiologie (v.a. Rektumresektion) wurde bei einem Teil der Patientinnen bereits ein Stoma im Rahmen der Primäroperation angelegt. Die Indikation zur Stomaanlage sollte sich in erster Linie nach dem Ausmaß des lokalen Defektes und der daraus resultierenden Belastung der betroffenen Frau richten.

Schlussfolgerung: In dieser klinischen Leitlinie werden zum ersten Mal in Deutschland Richtlinien für die Behandlung der rektovaginalen Fisteln basierend auf einer systematischen Literaturanalyse vorgestellt. Aufgrund des niedrigen Evidenzniveaus kann die vorliegende Leitlinie nur einen deskriptiven Charakter haben. Empfehlung für Diagnostik und Therapie beruhen überwiegend auf den klinischen Erfahrungen der Leitliniengruppe und können nicht durch die vorhandene Literatur komplett abgedeckt werden.

Introduction

Rectovaginal fistula (RVF) is defined as an epithelium-lined abnormal communication between rectum and vagina. It is reported to represent approximately 5% of all anorectal fistulas [1]. For affected women, the passing of air and secretions or stool from the rectum through the vagina represents a psychosocial burden that, of course, increases with the diameter of the fistula. RVF can result in recurrent infections of the vagina or lower urinary tract. In terms of etiology, various types of RVF are distinguished. Principal causes are obstetric trauma or iatrogenic trauma following procedures in the perineal and pelvic region. RVF can also arise as a result of local inflammations or tumors.

This S3 Guideline aims to present the clinical picture and treatment options on the basis of an evidence-based review of the available literature.

Methods

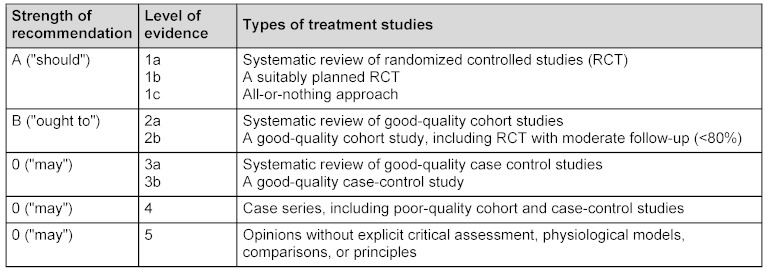

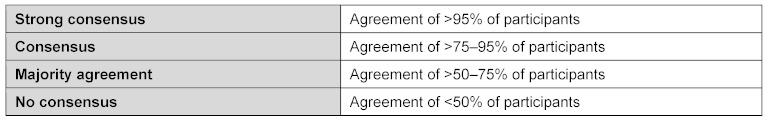

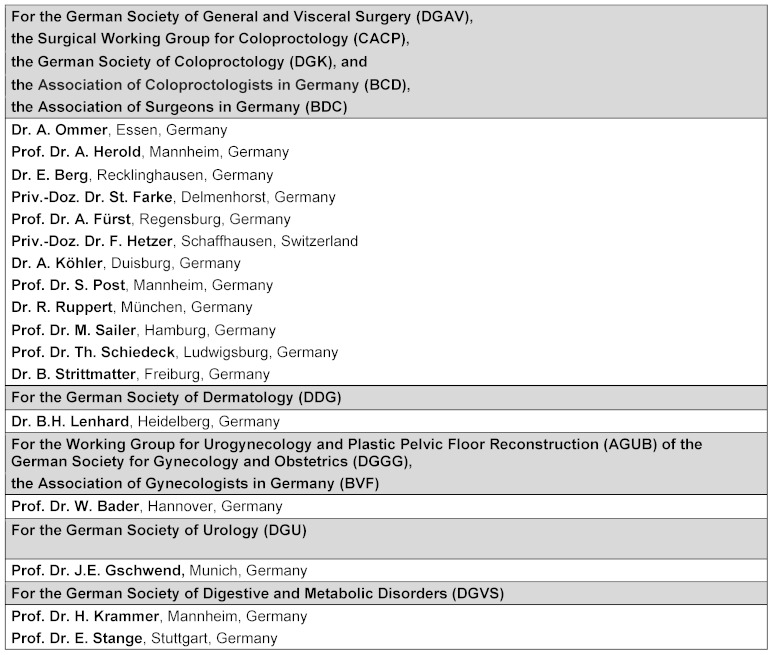

The content of the present guideline is based on an extensive review of literature. Definitions of strength of evidence, recommendation grade, and strength of consensus have been established elsewhere [2], [3], [4] (Table 1 (Tab. 1), Table 2 (Tab. 2)). In some cases, due to a large difference between evidence level and clinical practice, the recommendation grade was defined as “point of clinical consensus”. The guidelines group (Table 3 (Tab. 3)) produced the text [5] in the context of two consensus conferences. All medical societies agreed with the text.

Table 1. Definition of evidence levels and recommendation grades [2, 3].

Table 2. Classification of the strength of consensus [4].

Table 3. Members of the anal fistula guidelines group.

Epidemiology

The majority of rectovaginal fistulas, 88%, are caused by obstetric trauma (postpartum rectovaginal fistula). The total number of cases corresponds to 0.1% of all vaginal births [6]. Rectovaginal fistula occurs in 0.2–2.1% of patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (particularly Crohn's disease) [1], and following low anterior rectal resection, the frequency is as high as 10% [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. In recent years, rectovaginal fistula has been an increasingly common complication following hemorrhoid or pelvic floor surgery, particularly in cases where staplers or foreign materials were used [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. No statistics are available since the results have primarily been published in the form of case studies.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Classification

No generally accepted classification of rectovaginal fistulas exists. Most classifications are based on size, localization, and etiology. Since the vast majority of fistulas are of traumatic origin, no natural relationships are available as a basis for classification. In view of the surgical procedure, it makes sense to distinguish between low and high rectovaginal fistulas. Low fistulas are those that can be reconstructed via an anal, perineal, or vaginal access, while high fistulas require an abdominal approach. Some publications [7] describe anovaginal fistulas that terminate directly at the introitus without contact to the vaginal tube and typically arise from the anal canal. Fistulas in the central third are very rare due to the location and the characteristics of the vaginal wall; for high fistulas, there is no sharp distinction to colovaginal fistulas, which typically occur secondary to hysterectomy and terminate in the vaginal cuff, which represents a weak point [8]. The assessment of any perineal defects is also important for treatment planning.

Recommendation level: Point of clinical consensus (PCC)

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Etiology

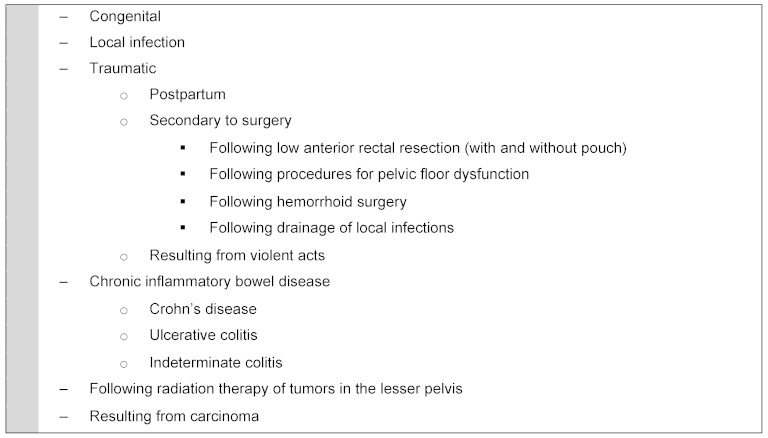

Only a small percentage of rectovaginal fistulas is of cryptoglandular origin [9]. Rectovaginal fistulas are frequently experienced in the postpartum period, some as a result of perineal tears. Another type is rectovaginal fistula in chronic inflammatory bowel disease (especially Crohn's disease). Rectal surgery with low anastomosis, with or without pouch, can also lead to the formation of rectovaginal fistulas. Table 4 (Tab. 4) presents an overview of possible causes.

Table 4. Etiology of rectovaginal fistulas.

Fistulas arising in conjunction with pelvic procedures can be caused by various postoperative complications, primarily direct trauma (perforation) that is not identified or inadequately treated intraoperatively. Secondary fistulas can arise in case of suture insufficiency following treatment of a defect in the context of infection. They may also arise as a result of secondary infection of a hematoma.

1. Obstetric rectovaginal fistula

Particularly in older publications, obstetric fistulas are reported to represent 88% of rectovaginal fistulas, rendering them the most common type [7]. These fistulas result from undue stretching with laceration of the perineum and the rectovaginal septum [10].

In a review of 24,000 vaginal births, Goldaber et al. [11] reported an incidence of 1.7% for fourth-degree perineal trauma and 0.5% for rectovaginal fistula. A current US study reports that fistulas associated with obstetric trauma have become less common [12].

As a result of their etiology, postpartum rectovaginal fistulas are often found in conjunction with sphincter lesions with fecal incontinence. Therefore, a thorough assessment is required in this regard. Many publications describe simultaneous anal sphincter reconstruction [13], [14], [15], [16].

Evidence level: IIb

Recommendation level: B

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

2. Rectovaginal fistulas resulting from local infection

Rectovaginal fistulas may also be caused by local infections, particularly cryptoglandular infections and Bartholin gland abscesses [17]. However, it seems unlikely that the inflammation simultaneously erodes the rectum and vagina (possibly in a protracted course), particularly since there is no primary connection to the rectum, unlike in cryptoglandular anal fistula [18]. Fistulas have also been reported as arising from foreign body erosion.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

3. Rectovaginal fistula secondary to rectal resection

In addition to the potential injury to the vagina during preparation, the use of staplers represents a risk factor for the development of rectovaginal fistulas secondary to rectal surgery with or without pouch creation. Fistulas are primarily described in up to 10% of low anastomoses [19], [20]. An important risk factor appears to be the use of staplers, especially if the so called double stapling technique is applied [19], [21], [22].

Another risk factor for the development of postoperative fistulas is preoperative or postoperative radiochemotherapy [23].

Pouch-vaginal fistulas are more common after surgical therapy of chronic inflammatory bowel disease than after proctocolectomy for polyposis coli [24]. The reported incidence is 6.3% of female patients [25].

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

4. Rectovaginal fistulas secondary to other surgical procedures at the rectum and lesser pelvis

With the increase of reconstructive procedures in the pelvic floor region, the number of publications on fistula formation between the rectum and vagina has risen as well. Procedures include transanal tumor resection (anterior rectal wall), hemorrhoid surgery using staplers, and procedures for pelvic floor disorders (descent, rectal prolapse, rectocele, incontinence) using staplers or mesh implantation.

While rectovaginal fistulas are an absolute rarity after conventional hemorrhoid surgery, cases of postoperative fistulas have been increasingly reported since the introduction of stapler hemorrhoidopexy [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. They are usually caused by errors in surgical technique, where the posterior vaginal wall is also caught in the stapler.

Another suspected cause of the rising incidence of rectovaginal fistula is the introduction of the more technically challenging STARR (Stapled Trans Anal Rectal Resection) and TRANSTAR (Transanal Stapled Resection) procedures [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36].

In general, iatrogenic or iatrogenic-traumatic rectovaginal fistulas can also result from other procedures at the ventral rectum (tumor resection [37], [38], rectocele repair [39], anal sphincter reconstruction), in sacrocolpopexy [40], and procedures at the dorsal vagina (posterior colporraphy) through injury of the respective other organ with inadequate treatment or postoperative suture dehiscence. Few related publications exist. Experience is more commonly derived from clinical practice or personal reports.

In fistulas following mesh implantation, which is now increasingly used in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction [41], [42], technical problems and local infections caused by the foreign materials play an important role [43], [44]. At a rate of 0.15%, these fistulas are reported as rare complications [45].

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

5. Rectovaginal fistulas secondary to radiotherapy

Some case reports have been published on fistulas secondary to radiotherapy [46], [47], [48]. It is important to distinguish between an elevated risk of developing postoperative rectovaginal fistulas in the rectum following prior radiotherapy versus spontaneously arisen fistulas under radiotherapy as a result of tumor growth or local radiogenic damage to the vaginal and rectal wall. Problems particularly arise due to radiogenic damage of the rectal wall, which can cause fistulas or stenoses. The surgical repair of these changes is often highly complex [49]. The surgical procedure must be planned based on the individual situation.

6. Rectovaginal fistulas in case of malignancies

Direct invasion of the respective other organ (e.g., the rectum in case of gynecological malignancies or the vagina in case of anal or rectal carcinoma) can cause fistulas as well. Typical closure techniques are usually not suitable in these cases, so that these fistulas cannot be covered in this guideline.

7. Colovaginal fistulas

Colovaginal fistulas must be distinguished from rectovaginal fistulas [8]. The most common cause is diverticulitis with occult perforation in the lesser pelvis. These fistulas are also not covered by this guideline.

Symptoms and diagnostics

The diagnosis of rectovaginal fistula is primarily based on the patient history and the clinical examination [50]. Patients typically report air, mucus, and possibly stool discharge through the vagina. Most commonly, rectovaginal fistulas are located at the height of the dentate line and communicate with the posterior vaginal fornix.

Especially in case of unclear findings, additional examinations should be considered before surgical intervention; these examinations particularly include colonoscopy and tomography of the lesser pelvis (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) to rule out accompanying pathologies (especially malignancies). They are dispensable in patients with a clear etiology (postpartum fistulas in young women).

Regarding the value of sonography and MRI in fistula confirmation, please refer to the respective section in the clinical practice guideline “Cryptoglandular anal fistula” [18], [51]. However, endosonography is a recognized, good alternative, particularly in the confirmation of sphincter lesions [52], [53]. A high level of evidence in the form of randomized studies and reviews is available on this topic. For surgical planning, it is recommended to assess sphincter function in a clinical examination (digital exam, possibly incontinence score, possibly manometry) and endosonography.

Recommendation level: Point of clinical consensus (PCC)

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Treatment procedures

The treatment of rectovaginal fistulas presents a special surgical challenge. The majority of the fistulas are high transsphincteric to extrasphincteric, so that division alone is generally inadequate.

The results for the surgical treatment of rectovaginal fistula have been compiled in evidence tables that are published with the complete German text [5]. Most studies report on a mixed patient group, and the respective data are not always analyzed separately. Breakdown by surgical techniques and different etiologies often results in small patient groups that are therefore only considered case reports.

The surgical treatment of rectovaginal fistulas largely corresponds to the treatment of high transsphincteric anal fistulas. The most common procedure is fistula excision with sphincter suture and closure of the ostium in the rectum by an advancement flap.

However, please note that the literature on rectovaginal fistula is generally published under the primary consideration of “healing." Treatment is primarily determined by the local circumstances such as localization and size of the fistula and the tissue situation (inflammation, sphincter lesion) [54]. This means that in many cases, revision surgeries until final closure of the rectovaginal fistula were also taken into consideration and included in the same study.

No randomized trials or relevant reviews or guidelines are available on the surgical treatment of rectovaginal fistulas. All existing reviews of the literature merely cover Crohn’s fistulas [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

1. Endorectal closure

The endorectal closure technique essentially corresponds to the flap technique in high anal fistulas [18], [51]. The literature includes 39 studies from 1978 through 2011 that cover this technique, with additional sphincteroplasty being performed in six of them. No prospective or randomized studies are available.

The more recent studies paint a differentiated picture, with healing rates ranging from 41% to 100%. Realistic success rates are probably between 50% and 70%.

The various etiologies are generally not differentiated, but it is likely that the results are much better for postpartum fistulas in younger women than for radiogenic fistulas in older patients. In some studies, simultaneous anal sphincter reconstruction is performed, so that no sharp distinction can be drawn to transperineal procedures. The two studies that compare the results with and without anal sphincter reconstruction reveal a trend toward better results for reconstruction [60], [61]. No relevant information is available on secondary recurrence and influence on continence.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

2. Transvaginal closure

Very few publications are available on the transvaginal approach. Among the 11 identified publications, seven are case reports. Two papers [62], [63] use case reports to describe a combined laparoscopic-transvaginal procedure in higher rectovaginal fistulas. In summary, no recommendations can be made regarding this procedure on the basis of currently available literature.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

3. Transperineal closure

Another treatment option is the transperineal approach, where the rectum is first separated from the vagina via a perineal incision. Following separate adaptation of the mucosa, sphincter, and vaginal mucosa, the rectovaginal septum is augmented through adaptation of the levator muscle. Especially in patients with postpartum sphincter lesions, sphincteroplasty can be performed in the same session [54], [64]. Herein lies the key advantage of this procedure [65]. This illustrates the relevance of preoperative examination with respect to incontinence and sphincter lesions. In case of corresponding abnormalities, simultaneous anal sphincter reconstruction is recommended [65]. A disadvantage of this procedure is the relatively extensive surgical trauma (perineal wound) with the risk of impaired wound healing. The results of the few larger retrospective studies do not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn.

Transperineal procedures also include episioproctotomy, in which all tissue above the fistula is cut and then reconstructed in layers. The literature reports healing rates between 35% and 100%.

Recommendation level: Point of clinical consensus (PCC)

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

4. Martius procedure

The Martius procedure uses a pedicled flap of adipose tissue from the labia majora [66]. The interposition of well-vascularized tissue is intended to separate and protect the vaginal from the rectal sutures. A speciall technique consists in interposition of the bulbocavernosus muscle [67]. Overall, the Martius flap operation is a rare procedure. We were able to analyze 14 papers, some of which were case studies. The procedure is primarily used in case of recurrences. High cure rates are reported in selected patient groups.

Evidence level: IV

Recommendation level: 0

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

5. Gracilis interposition

Augmentation of the rectovaginal septum can also be achieved by unilateral or bilateral interposition of the gracilis muscle A speciall technique consists in interposition of the bulbocavernosus muscle [68]. In general, gracilis interposition is much more complex and invasive than the Martius flap operation. The goal of the procedure is to strengthen the rectovaginal septum by interposing the well-vascularized muscle following direct closure of the corresponding fistula orifices. Like Martius-procedure the gracilis interposition is primarily used in case of recurrences. High cure rates are reported in selected patient groups [69], especially in patients with Crohn’s disease.

Evidence level: V

Recommendation level: 0

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

6. Miscellaneous procedures

The so-called sleeve anastomosis is a special and highly invasive procedure. It is based on mobilization and resection of the distal rectum. Reanastomosis, usually via a transanal manual suture, is performed following removal of the fistula-bearing or destroyed area. The procedure is primarily used in patients with significant rectal wall defects due to chronic inflammatory bowel disease or following radiation therapy.

Another procedures consisted in treatment with autologous stem cells [70].

The successful treatment of rectovaginal fistula using a circular stapler is another special treatment, which has only been published in one case report [71].

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

7. Interposition of biomaterials

Treatment results using fibrin adhesive, fistula plug, or biomembrane have also only been published in the form of case reports, and highly divergent success rates of between 0% and 100% are reported. In total, 19 publications report on a total of 131 patients. For the purpose of this guideline, the value of biomaterials, which are increasingly used, cannot be assessed at this point in time.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

8. Abdominal techniques

Higher fistulas can also be treated by resection of the affected part of the intestine with primary rectal anastomosis using conventional [72] or laparoscopic techniques [73]. It is difficult to differentiate this technique from the treatment of colovaginal fistulas in cases of diverticular disease. Only one publication reports on a larger patient group [73], with cure rates of nearly 100% in various etiologies.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Perioperative management

1. Wound management and perioperative complications

Complications following rectovaginal fistula surgery are generally similar to those following other anal procedures [74]. Plastic reconstruction of fistulas is associated with a risk of local infection with secondary suture dehiscence. In most cases, suture dehiscence is associated with persistence of the fistula.

Relevant postoperative complications include dyspareunia resulting from vaginal stenosis or scar formation [75]. It is reported to arise in up to 25% of sexually active patients [76], [77].

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

2. Postoperative return to normal diet

The follow-up treatment after complex anal procedures is subject to ongoing controversy. There is general consensus that avoiding the passage of stool through the fresh wound benefits the healing process. This particularly applies to avoiding strong pressing, especially after sphincter sutures. No definitive studies on this topic are currently available. The same is true for the role of perioperative and/or postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

3. Ostomy

While ostomy is rarely required in the context of anal fistula surgery [78], the rate is much higher in rectovaginal fistulas, although no relevant studies are currently available. Ostomy is primarily indicated in case of extensive destruction of the anal canal with resulting fecal incontinence.

In general, the decision must be made on the basis of the local and individual situation. Depending on the etiology (esp. rectal resection), a stoma may already be in place in some of the patients as a result of the primary surgery. In all other cases, the decision on secondary stoma creation must be made on an individual basis. The personal physical and psychological burden on the patient resulting from the local inflammation and the extent of secretion through the fistula is an important consideration in the decision process. Particularly in case of postoperative dehiscence, a major burden can result, for instance, due to enlargement of the defect following fistula excision.

Recommendation level: Point of clinical consensus (PCC)

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

4. Continence

Please refer to the anal fistula guideline [18], [51] regarding the role of incontinence. The premises described in that guideline also apply to anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas. Rectovaginal fistulas regularly involve the entire sphincter apparatus, so that pure division is always associated with relevant incontinence. Simultaneously, there is a risk of the formation of a cloaca. Incontinence resulting from the treatment of rectovaginal fistula plays a subordinate role in the literature since “healing” is the primary focus. The simultaneous reconstruction of sphincter lesions can improve continence.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Conclusions

-

The majority of rectovaginal fistulas are of traumatic origin. The most common causes are obstetric trauma, local infection, and rectal surgery.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

-

Persistent rectovaginal fistulas generally require surgical treatment.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

-

Rectovaginal fistula is diagnosed based on the patient history and the clinical examination. Other pathologies should be ruled out through additional examinations (endoscopy, endosonography, tomography). The assessment of sphincter function is valuable for surgical planning (potential simultaneous sphincter reconstruction).

Evidence level: IIb

Recommendation level: B

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

-

Various surgical procedures have been described, but evidence levels are low. The most common procedure is transrectal surgery with endorectal suture. The transperineal approach is primarily used in case of simultaneous anal sphincter reconstruction. Closure can also be achieved through the interposition of autologous tissue (Martius flap, gracilis muscle) or biomaterials. Autologous tissue is predominantly used in recurrent fistulas. In higher fistulas, abdominal approaches are also used. No specific procedure can be recommended on the basis of the literature.

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

-

Ostomy is more frequently required in rectovaginal fistulas than in anal fistulas. Depending on the etiology (esp. rectal resection), a stoma may already be in place in some of the patients as a result of the primary surgery. The decision on stoma creation should be primarily made on the basis of the extent of the local defect and the resulting burden on the patient.

Recommendation level: Point of clinical consensus (PCC)

Strength of consensus: Strong consensus

Notes

Annotation

The complete text of the guideline (in German) has been published in Coloproctology 2012;(34):211-246 and online at: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/088-004.html (AWMF register no. 088-004).

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Ommer received an honorarium from the DGAV for generating four guidelines on anal fistula. Furthermore, some of his travel and accommodation costs were reimbursed by Gore and Johnson & Johnson. He received an honorarium for presentations at continued education events from Kade and MSD.

Prof. Herold received financial support for conferences from the Falk Foundation, Johnson & Johnson, Prostrakan, MSD, and Aesculap. Additional projects were supported by external funding from the following companies: Cook, Gore, SLA-Pharma, Falk-Foundation, and Kreussler.

Dr. Berg was reimbursed for conference registration fees as well as travel and accommodation costs by Johnson & Johnson. He received an honorarium from Falk Foundation and Johnson & Johnson for preparatory work associated with continued education events.

Prof. Fürst received funding for conference travel from Johnson & Johnson and Braun-Aeskulap, and he received an honorarium for conducting commissioned clinical studies from Bayern Innovativ GmbH.

Prof. Schiedeck was reimbursed for registration fees and travel and accommodation costs and received an honorarium for preparatory work associated with scientific continued education events by Aesculap Akademie GmbH, Falk Foundation e.V., Johnson & Johnson, and Medical GmbH. He received an honorarium from Solesta and Medela for conducting commissioned clinical studies.

Prof. Sailer received an honorarium for continued education events from Covidien, Johnson & Johnson, Falk Foundation, and Hitachi Medical.

References

- 1.Tsang CB, Rothenberger DA. Rectovaginal fistulas. Therapeutic options. Surg Clin North Am. 1997 Feb;77(1):95–114. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70535-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmiegel W, Reinacher-Schick A, Arnold D, Graeven U, Heinemann V, Porschen R, Riemann J, Rödel C, Sauer R, Wieser M, Schmitt W, Schmoll HJ, Seufferlein T, Kopp I, Pox C. S3-Leitlinie "Kolorektales Karzinom" - Aktualisierung 2008. [Update S3-guideline "colorectal cancer" 2008]. Z Gastroenterol. 2008 Aug;46(8):799–840. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027726. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1027726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips B, Ball C, Sackett D, et al. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based medicine—levels of evidence. 2009. Available from: http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann JC, Fischer I, Höhne W, Zeitz M, Selbmann HK. Methodische Grundlagen für die Ableitung von Konsensusempfehlungen. [Methodological basis for the development of consensus recommendations]. Z Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;42(9):984–986. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813496. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-813496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, et al. S3-Leitlinie: Rektovaginale Fisteln (ohne M.Crohn) Coloproctology. 2012;34:211–246. doi: 10.1007/s00053-012-0287-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00053-012-0287-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homsi R, Daikoku NH, Littlejohn J, Wheeless CR., Jr Episiotomy: risks of dehiscence and rectovaginal fistula. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994 Dec;49(12):803–808. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199412000-00002. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006254-199412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senatore PJ., Jr Anovaginal fistulae. Surg Clin North Am. 1994 Dec;74(6):1361–1375. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahadursingh AM, Longo WE. Colovaginal fistulas. Etiology and management. J Reprod Med. 2003 Jul;48(7):489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saclarides TJ. Rectovaginal fistula. Surg Clin North Am. 2002 Dec;82(6):1261–1272. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00055-5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genadry RR, Creanga AA, Roenneburg ML, Wheeless CR. Complex obstetric fistulas. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007 Nov;99 Suppl 1:S51–S56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.026. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldaber KG, Wendel PJ, McIntire DD, Wendel GD., Jr Postpartum perineal morbidity after fourth-degree perineal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Feb;168(2):489–493. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown HW, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Lower reproductive tract fistula repairs in inpatient US women, 1979-2006. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Apr;23(4):403–410. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1653-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-011-1653-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delancey JO, Miller NF, Berger MB. Surgical approaches to postobstetrical perineal body defects (rectovaginal fistula and chronic third and fourth-degree lacerations) Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Mar;53(1):134–144. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cf7488. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cf7488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanduja KS, Padmanabhan A, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Aguilar PS. Reconstruction of rectovaginal fistula with sphincter disruption by combining rectal mucosal advancement flap and anal sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999 Nov;42(11):1432–1437. doi: 10.1007/BF02235043. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02235043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanduja KS, Yamashita HJ, Wise WE, Jr, Aguilar PS, Hartmann RF. Delayed repair of obstetric injuries of the anorectum and vagina. A stratified surgical approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994 Apr;37(4):344–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02053595. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02053595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCall ML. Gynecological aspects of obstetrical delivery. Can Med Assoc J. 1963 Jan;88:177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoulek E, Karp DR, Davila GW. Rectovaginal fistula as a complication to a Bartholin gland excision. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;118(2 Pt 2):489–491. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182235548. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182235548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, Fürst A, Sailer M, Schiedeck T. Cryptoglandular anal fistulas. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 Oct;108(42):707–713. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0707. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosugi C, Saito N, Kimata Y, Ono M, Sugito M, Ito M, Sato K, Koda K, Miyazaki M. Rectovaginal fistulas after rectal cancer surgery: Incidence and operative repair by gluteal-fold flap repair. Surgery. 2005 Mar;137(3):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.004. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthiessen P, Hansson L, Sjödahl R, Rutegård J. Anastomotic-vaginal fistula (AVF) after anterior resection of the rectum for cancer--occurrence and risk factors. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Apr;12(4):351–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01798.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yodonawa S, Ogawa I, Yoshida S, Ito H, Kobayashi K, Kubokawa R. Rectovaginal Fistula after Low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer Using a Double Stapling Technique. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2010;4(2):224–228. doi: 10.1159/000318745. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000318745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin US, Kim CW, Yu CS, Kim JC. Delayed anastomotic leakage following sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010 Jul;25(7):843–849. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-0938-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-010-0938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim CW, Kim JH, Yu CS, Shin US, Park JS, Jung KY, Kim TW, Yoon SN, Lim SB, Kim JC. Complications after sphincter-saving resection in rectal cancer patients according to whether chemoradiotherapy is performed before or after surgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010 Sep;78(1):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1684. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gecim IE, Wolff BG, Pemberton JH, Devine RM, Dozois RR. Does technique of anastomosis play any role in developing late perianal abscess or fistula? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Sep;43(9):1241–1245. doi: 10.1007/BF02237428. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02237428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lolohea S, Lynch AC, Robertson GB, Frizelle FA. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis-vaginal fistula: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005 Sep;48(9):1802–1810. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0079-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angelone G, Giardiello C, Prota C. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Complications and 2-year follow-up. Chir Ital. 2006 Nov-Dec;58(6):753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giordano P, Gravante G, Sorge R, Ovens L, Nastro P. Long-term outcomes of stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs conventional hemorrhoidectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Surg. 2009 Mar;144(3):266–272. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.591. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2008.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giordano P, Nastro P, Davies A, Gravante G. Prospective evaluation of stapled haemorrhoidopexy versus transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation for stage II and III haemorrhoids: three-year outcomes. Tech Coloproctol. 2011 Mar;15(1):67–73. doi: 10.1007/s10151-010-0667-z. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10151-010-0667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beattie GC, Loudon MA. Haemorrhoid surgery revised. Lancet. 2000 May;355(9215):1648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72555-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72555-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giordano A, della Corte M. Non-operative management of a rectovaginal fistula complicating stapled haemorrhoidectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008 Jul;23(7):727–728. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0416-6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassi R, Rademacher J, Savoia A. Rectovaginal fistula after STARR procedure complicated by haematoma of the posterior vaginal wall: report of a case. Tech Coloproctol. 2006 Dec;10(4):361–363. doi: 10.1007/s10151-006-0310-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10151-006-0310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naldini G. Serious unconventional complications of surgery with stapler for haemorrhoidal prolapse and obstructed defaecation because of rectocoele and rectal intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Mar;13(3):323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02160.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gagliardi G, Pescatori M, Altomare DF, Binda GA, Bottini C, Dodi G, Filingeri V, Milito G, Rinaldi M, Romano G, Spazzafumo L, Trompetto M. Results, outcome predictors, and complications after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Feb;51(2):186–195. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9096-0. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-007-9096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martellucci J, Talento P, Carriero A. Early complications after stapled transanal rectal resection performed using the Contour® Transtar™ device. Colorectal Dis. 2011 Dec;13(12):1428–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02466.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pescatori M, Dodi G, Salafia C, Zbar AP. Rectovaginal fistula after double-stapled transanal rectotomy (STARR) for obstructed defaecation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005 Jan;20(1):83–85. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0658-5. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-004-0658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pescatori M, Zbar AP. Reinterventions after complicated or failed STARR procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009 Jan;24(1):87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0556-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mortensen C, Mackey P, Pullyblank A. Rectovaginal fistula: an unusual presentation. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Jul;12(7):703–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02000.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krissi H, Levy T, Ben-Rafael Z, Levavi H. Fistula formation after large loop excision of the transformation zone in patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001 Dec;80(12):1137–1138. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801211.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Calabrò G, Trompetto M, Ganio E, Tessera G, Bottini C, Pulvirenti D'Urso A, Ayabaca S, Pescatori M. Which surgical approach for rectocele? A multicentric report from Italian coloproctologists. Tech Coloproctol. 2001 Dec;5(3):149–156. doi: 10.1007/s101510100017. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s101510100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimmerman DD, Gosselink MP, Briel JW, Schouten WR. The outcome of transanal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal fistulas is not improved by an additional labial fat flap transposition. Tech Coloproctol. 2002 Apr;6(1):37–42. doi: 10.1007/s101510200007. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s101510200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Devaseelan P, Fogarty P. Review The role of synthetic mesh in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2009;11(3):169–176. doi: 10.1576/toag.11.3.169.27501. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1576/toag.11.3.169.27501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huffaker RK, Shull BL, Thomas JS. A serious complication following placement of posterior Prolift. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009 Nov;20(11):1383–1385. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0873-2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen HW, Guess MK, Connell KA, Bercik RS. Ischiorectal abscess and ischiorectal-vaginal fistula as delayed complications of posterior intravaginal slingplasty: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2009 Oct;54(10):645–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilger WS, Cornella JL. Rectovaginal fistula after Posterior Intravaginal Slingplasty and polypropylene mesh augmented rectocele repair. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Jan;17(1):89–92. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1354-x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00192-005-1354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caquant F, Collinet P, Debodinance P, Berrocal J, Garbin O, Rosenthal C, Clave H, Villet R, Jacquetin B, Cosson M. Safety of Trans Vaginal Mesh procedure: retrospective study of 684 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008 Aug;34(4):449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00820.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson JR, Spence RA, Parks TG, Bond EB, Burrows BD. Rectovaginal fistulae following radiation treatment for cervical carcinoma. Ulster Med J. 1984;53(1):84–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooke SA, Wellsted MD. The radiation-damaged rectum: resection with coloanal anastomosis using the endoanal technique. World J Surg. 1986 Apr;10(2):220–227. doi: 10.1007/BF01658138. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01658138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Narayanan P, Nobbenhuis M, Reynolds KM, Sahdev A, Reznek RH, Rockall AG. Fistulas in malignant gynecologic disease: etiology, imaging, and management. Radiographics. 2009 Jul-Aug;29(4):1073–1083. doi: 10.1148/rg.294085223. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.294085223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bricker EM, Johnston WD, Patwardhan RV. Repair of postirradiation damage to colorectum: a progress report. Ann Surg. 1981 May;193(5):555–564. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198105000-00004. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000658-198105000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kröpil F, Raffel A, Renter MA, Schauer M, Rehders A, Eisenberger CF, Knoefel WT. Individualisierte und differenzierte Therapie von rektovaginalen Fisteln. [Individualised and differentiated treatment of rectovaginal fistula]. Zentralbl Chir. 2010 Aug;135(4):307–311. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247475. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1247475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ommer A, Herold A, Berg E, et al. S3-Leitlinie Kryptoglanduläre Analfistel. Coloproctology. 2011;33:295–324. doi: 10.1007/s00053-011-0210-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00053-011-0210-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoker J, Rociu E, Wiersma TG, Laméris JS. Imaging of anorectal disease. Br J Surg. 2000 Jan;87(1):10–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01338.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Jakubowski W, Szczepkowski M. Contrast-enhanced endosonography for the diagnosis of anal and anovaginal fistulas. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002 Mar-Apr;30(3):145–150. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10042. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcu.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russell TR, Gallagher DM. Low rectovaginal fistulas. Approach and treatment. Am J Surg. 1977 Jul;134(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90277-X. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(77)90277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Penninckx F, Moneghini D, D'Hoore A, Wyndaele J, Coremans G, Rutgeerts P. Success and failure after repair of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: analysis of prognostic factors. Colorectal Dis. 2001 Nov;3(6):406–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2001.00274.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1463-1318.2001.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andreani SM, Dang HH, Grondona P, Khan AZ, Edwards DP. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Dec;50(12):2215–2222. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9057-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-007-9057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hannaway CD, Hull TL. Current considerations in the management of rectovaginal fistula from Crohn's disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Oct;10(8):747–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01552.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruffolo C, Scarpa M, Bassi N, Angriman I. A systematic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: transrectal vs transvaginal approach. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Dec;12(12):1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02029.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu YF, Tao GQ, Zhou N, Xiang C. Current treatment of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Feb;17(8):963–967. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.963. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baig MK, Zhao RH, Yuen CH, Nogueras JJ, Singh JJ, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Simple rectovaginal fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000 Nov;15(5-6):323–327. doi: 10.1007/s003840000253. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003840000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lowry AC, Thorson AG, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM. Repair of simple rectovaginal fistulas. Influence of previous repairs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988 Sep;31(9):676–678. doi: 10.1007/BF02552581. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02552581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pelosi MA, 3rd, Pelosi MA. Transvaginal repair of recurrent rectovaginal fistula with laparoscopic-assisted rectovaginal mobilization. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1997 Dec;7(6):379–383. doi: 10.1089/lap.1997.7.379. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/lap.1997.7.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herbst F, Jakesz R. Method for treatment of large high rectovaginal fistula. Br J Surg. 1994 Oct;81(10):1534–1535. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811046. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800811046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mengert WF, Fish SA. Anterior rectal wall advancement; technic for repair of complete perineal laceration and recto-vaginal fistula. Obstet Gynecol. 1955 Mar;5(3):262–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsang CB, Madoff RD, Wong WD, Rothenberger DA, Finne CO, Singer D, Lowry AC. Anal sphincter integrity and function influences outcome in rectovaginal fistula repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Sep;41(9):1141–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF02239436. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02239436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gosselink MP, Oom DM, Zimmerman DD, Schouten RW. Martius flap: an adjunct for repair of complex, low rectovaginal fistula. Am J Surg. 2009 Jun;197(6):833–834. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.023. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cui L, Chen D, Chen W, Jiang H. Interposition of vital bulbocavernosus graft in the treatment of both simple and recurrent rectovaginal fistulas. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009 Nov;24(11):1255–1259. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0720-4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-009-0720-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruiz D, Bashankaev B, Speranza J, Wexner SD. Graciloplasty for rectourethral, rectovaginal and rectovesical fistulas: technique overview, pitfalls and complications. Tech Coloproctol. 2008 Sep;12(3):277–281. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0433-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10151-008-0433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fürst A, Schmidbauer C, Swol-Ben J, Iesalnieks I, Schwandner O, Agha A. Gracilis transposition for repair of recurrent anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008 Apr;23(4):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0413-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.García-Olmo D, García-Arranz M, García LG, Cuellar ES, Blanco IF, Prianes LA, Montes JA, Pinto FL, Marcos DH, García-Sancho L. Autologous stem cell transplantation for treatment of rectovaginal fistula in perianal Crohn's disease: a new cell-based therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003 Sep;18(5):451–454. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0490-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-003-0490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Destri G, Scilletta B, Tomaselli TG, Zarbo G. Rectovaginal fistula: a new approach by stapled transanal rectal resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 Mar;12(3):601–603. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0333-6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11605-007-0333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kux M, Fuchsjäger N, Hirbawi A. Einzeitige anteriore Resektion in der Therapie hoher recto-vaginaler Fisteln. [One-stage anterior resection in the therapy of high rectovaginal fistulas]. Chirurg. 1986 Mar;57(3):150–154. (Ger). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van der Hagen SJ, Soeters PB, Baeten CG, van Gemert WG. Laparoscopic fistula excision and omentoplasty for high rectovaginal fistulas: a prospective study of 40 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011 Nov;26(11):1463–1467. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1259-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-011-1259-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Toyonaga T, Matsushima M, Sogawa N, Jiang SF, Matsumura N, Shimojima Y, Tanaka Y, Suzuki K, Masuda J, Tanaka M. Postoperative urinary retention after surgery for benign anorectal disease: potential risk factors and strategy for prevention. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006 Oct;21(7):676–682. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0077-2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00384-005-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tunuguntla HS, Gousse AE. Female sexual dysfunction following vaginal surgery: a review. J Urol. 2006 Feb;175(2):439–446. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00168-0. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.El-Gazzaz G, Hull TL, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Obstetric and cryptoglandular rectovaginal fistulas: long-term surgical outcome; quality of life; and sexual function. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 Nov;14(11):1758–1763. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1259-y. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1259-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zmora O, Tulchinsky H, Gur E, Goldman G, Klausner JM, Rabau M. Gracilis muscle transposition for fistulas between the rectum and urethra or vagina. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 Sep;49(9):1316–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0585-3. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ommer A, Athanasiadis S, Köhler A, Psarakis E. Die Bedeutung der Stomaanlage im Rahmen der Behandlung der komplizierten Analfisteln und der rektovaginalen Fisteln. Coloproctology. 2000;22:14–22. doi: 10.1007/s00053-000-0002-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00053-000-0002-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schwenk W, Böhm B, Gründel K, Müller J. Laparoscopic resection of high rectovaginal fistula with intracorporeal colorectal anastomosis and omentoplasty. Surg Endosc. 1997 Feb;11(2):147–149. doi: 10.1007/s004649900318. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s004649900318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]