Abstract

A “Digital Divide” in information and technological literacy exists in Utah between small hospitals and clinics in rural areas and the larger health care institutions in the major urban area of the state. The goals of the outreach program of the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library at the University of Utah address solutions to this disparity in partnership with the National Network of Libraries of Medicine—Midcontinental Region, the Utah Department of Health, and the Utah Area Health Education Centers. In a circuit-rider approach, an outreach librarian offers classes and demonstrations throughout the state that teach information-access skills to health professionals. Provision of traditional library services to unaffiliated health professionals is integrated into the library's daily workload as a component of the outreach program. The paper describes the history, methodology, administration, funding, impact, and results of the program.

LIBRARY OUTREACH: ADDRESSING UTAH'S “DIGITAL DIVIDE”

President Clinton visited the Navajo Reservation in Shiprock, New Mexico, in April of 2000 on a “Digital Divide” tour to assess Internet inequities firsthand. Had he visited the reservation's Montezuma Creek, Utah, medical clinic, he would have been exposed to Internet disparities of another kind, that between Utah's rural and urban health care practitioners.

The state of Utah currently receives recognition and acclaim nationwide for its advanced statewide access to online information resources in a program called Pioneer for public libraries, public schools, and academic libraries. Large hospital and medical libraries in the Salt Lake City area, called the Wasatch Front, offer a wealth of connectivity to expensive electronic databases and resources. Training programs to introduce staff to new computer programs and Internet training are readily available. Access to information resources, both public and medical, have been carefully negotiated by institutions and consortia to gain the best advantage in price and ease of access for faculty, students, and staff.

By contrast, these opportunities are not translated into services and resources for health care practitioners in rural hospitals and clinics. Rural health care facilities in Utah are often connected to the Internet, but their budgets are limited and do not include funding for information-access training or subscriptions to expensive online databases. Moreover, they struggle to remain open, maintain computer access, and ward off takeovers by large corporations. The lower costs for subscriptions that are part of complex licensing agreements negotiated on behalf of libraries and colleges do not include access by hospitals or clinics. There is no advocacy group for rural health care institutions to negotiate advantageous pricing and licensing agreements and to offer a “Medical Pioneer” of online resources and services. This inequity between urban and rural health care institutional access to training and electronic patient care information represents a classical example of the Digital Divide.

A White House press release, “From Digital Divide to Digital Opportunity: A National Call to Action,” issued on April 6, 2000, has identified the critical need for information and technology literacy [1]. One of the major goals of the Outreach Program of the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library is to address that need and contribute to closing the health care information Digital Divide in Utah.

UTAH AT A GLANCE

Geographically, Utah covers 84,900 square miles and is ranked the eleventh largest state in the United States. However, the general population was estimated in 1999 at only 2,129,836 [2]. The state's frontier and rural counties cover 96% of the area, yet hold only 22% of its population, a population density of 24.4 people per square mile. Some parts of Utah are among the most isolated and least populated in the United States because of the large acreage held by the Bureau of Land Management and the lands dedicated to state recreational parks, the U.S. Forest Service, and the National Park Service. Fifteen of Utah's twenty-nine counties fall under the frontier designation, while ten qualify as rural, and only four are considered urban [3]. Rural and underserved residents in the state include ranchers and farmers, Native Americans, migrant and local Hispanic populations, several polygamous communities, rapidly growing Asian and Pacific Island populations, homeless individuals, and transients. Tourists from all over the world expect access to health care when visiting the state and represent an additional burden on the health care infrastructure.

Access to health care in rural Utah is affected by difficulties in recruiting and retaining professionals. The Utah Medical Association (UMA) estimates that about 4,000 physicians currently practice throughout the state, but there is still a serious shortage of health care providers in less populated regions. As a result, twenty-six of the state's twenty-nine counties are designated by the Federal Division of Shortage Designations, Bureau of Primary Health Care, in whole or in part, as Health Professional Shortage Areas [4].

Hospitals and clinics range from rural nonprofit and for-profit hospitals, federally funded community health clinics for rural and underserved urban populations, county-funded hospitals, and Indian Health Service clinics. The primary concentration of hospitals and providers exists along the Wasatch Front, a four-county area that extends from Provo to north of Salt Lake City. A major contributor to health resources in the state is the University of Utah Health Sciences Center (UUHSC) located in Salt Lake City. Students, faculty, and residents in these programs serve in clinical rotations and as preceptors throughout the state. In addition to overseeing the public health needs of citizens in the state, the Utah Department of Health works in conjunction with a network of twelve local health departments. Each of these agencies provides a variety of direct public health programs to local citizens in twelve regions of the state. Emergency medical technicians work on a volunteer basis in rural Utah. They fill an important role in rural health care by offering medical and rescue service to individuals, frequently tourists, who are injured, stranded, or lost.

INFORMATION RESOURCES

In 1997, an initiative to provide information resources electronically was proposed by the Utah Academic Library Consortium (UALC) and funded by the state legislature. The effort resulted in Pioneer, a system of state-funded electronic resources available at kindergarten through twelfth grade public schools, public libraries, and institutions of higher learning across the state. Proxy server access from off campus or offsite to these resources is provided by some academic institutions. Hospitals and clinics, some for-profit and others not-for-profit, without a mechanism for participating in the license-agreement negotiation with the information vendors are not included in Pioneer.

Other legislative funding initiatives orchestrated by UALC form the basis for collection development among all the state's colleges and universities. Eccles Library recently organized a “Nursing Initiative Workshop” to coordinate purchases of nursing curriculum support materials among libraries at institutions of higher education.

While the Utah Academic Library Consortium oversees the activities of the college and university libraries, hospital librarians participate in the Utah Health Sciences Library Consortium (UHSLC). The UHSLC institutional membership category is made up of libraries that share materials and work toward cooperative collection of resources within the consortium. Subscribers representing other member categories include institutions with no collection to share that receive library services as a benefit of membership. Of the twenty institutional members, only two of the three located outside the Wasatch Front offer a library collection of significant size, and they are located in the most northern and southwestern areas of the state. Therefore, proximity to medical library facilities and services are scarce beyond the Wasatch Front.

HISTORY OF LIBRARY OUTREACH AT ECCLES LIBRARY

As a state-supported institution and the only large health sciences library in the state, the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library remains committed to bringing up-to-date medical information to health care providers in the state of Utah. A philosophy of service and education is foremost in all Eccles Library programs.

Eccles Library has offered an outreach program for almost thirty years. In the 1970s, the extension program for statewide library development resulted in the formation of the Utah Health Sciences Library Consortium. In the mid-1980s, an Infonet project, funded by the National Library of Medicine (NLM), electronically linked Utah consortium hospital librarians with email and interlibrary loan capabilities using the Octanet software and local data. More recently, outreach at the Eccles Library has included providing library services on a contract basis to individual health care facilities as well as participation in the consortium. In 1992, as a result of strategic planning, a full-time librarian was recruited to develop the program further.

The current Outreach Program at the Eccles Library is the only one of its kind in the state. No other library, academic or health sciences, employs a librarian full time to provide training and services to health care providers at their site, on request. The program is not one that began as a preplanned and funded package to meet a specific set of objectives. It is one, however, that meets needs and evolves as funding, opportunities, and technology become available.

The program extends library services to all health professionals classified by NLM as unaffiliated, but specifically targets three interrelated groups: the University of Utah Health Sciences Center (UUHSC); staff, students, and professionals affiliated with the Area Health Education Centers (AHECs); and staff and service areas of the Utah Department of Health (DOH). These three groups identify and define the service population and geographical area of the program, in essence, the entire state.

The UUHSC audience includes students, faculty, and staff who rotate to or live in rural off-campus sites. Integral to this arrangement is the work of the Utah Area Health Education Center, whose mission is to “improve access to health care through education.” Because of the nature of AHEC programming, many of the recipients of AHEC services fall under the aegis of the UUHSC. The third program is available to the staff of rural and community health clinics served by the Bureau of Primary Care and Rural Health Services of the DOH.

PLANNING THE PROGRAM

As a first step in 1992, a planning map was created indicating the locations of all forty-seven health care centers in rural and underserved areas of the state. Planning was coordinated with rural health staff at the DOH and the Association for Utah Community Health. Staff members at a number of sites were contacted, and visits were made to fifteen. Attendees were given a demonstration of the Grateful Med software during ninety-minute sessions, were asked to complete a modified version of the National Library of Medicine Outreach Enhancement questionnaire, and participated in a discussion of their information needs. Survey results indicated that MEDLINE use of any kind prior to the training session was only about 10%. Sixty-eight percent had computer equipment available in their offices and 22% at home. The needs identified in the group discussions were: (1) locally offered continuing education, (2) ready computer access for searching from the office, and (3) a current-reference library.

Two focus groups conducted in 1996 identified the information needs of public health officials and hospital administrators. The local health officers spoke of their need for quality literature, statistics, and training. The major issues of concern among the small group of rural hospital administrators were staff turnover, flux in hospital ownership, time, and space. They had no budget for library materials or services and felt that when physicians needed articles, the administrators “found the money to pay for them.”

When planning for training sessions and classes, an informal assessment of the needs of the participants usually precedes each class. With small groups in rural areas, the participants invariably represent a mixed level of skills with different needs. Knowing these needs prior to the class is helpful; however, these differences are usually best addressed on a one-to-one basis during the class time period. Informal assessment of training needs occurs in conversations with professionals visiting the Eccles Library outreach table at local health provider meetings. Planning efforts point to the need for training to be brought to the sites as time away from work and the cost of travel to training in the Wasatch Front area are not part of institutional budgets. These findings again underscore the need for training as an outreach agenda.

PARTNERSHIPS

Partnerships are crucial to any outreach program, especially with one-person operations. Serendipity and luck resulted in the first partnership of the new outreach program. A rural outreach team at the DOH included Eccles Library in a five-year plan at the same time Eccles Library submitted a request to the National Network of Libraries of Medicine—Midcontinental Region (NN/LM—MR) for an outreach travel grant. The partnership resulted in a seven-year continuously funded collaboration, the DOH component of the Eccles Library Outreach Program: the Rural Medical Library Outreach Program. The hub of the Utah Telehealth Network (UTN), located at the UUHSC, linked sites around the state for using teleradiology and transmitting data and visual images. The Eccles Library Outreach Program collaborated with this group to provide training in computer use and information access over the Web. Classes have also been taught at UMA meetings and leadership training workshops.

The most recent partnership was with the Utah AHECs, which began receiving federal funding in September 1996. The library had already been in discussions with these newcomers on the Utah health education scene, regarding development of a program of information access. Under contract with the AHECs, the outreach librarian has coordinated library services for the centers as they hired staff and began operations. Training activities provided by the librarian were Internet and database training to health care professionals and an Internet searching and evaluating workshop for high school students in a Leadership Camp. Another project assessed the demand for support of interlibrary loan services for distance-learning students studying in health professions degree programs. Information resources Web pages for each center are under development.

METHODOLOGY

The methods used to implement the Eccles Library outreach program include training in Internet access and use of both library- and non-library-related resources, traditional library services, and Web-based and print products to facilitate access to electronic library services. Traditional library services consist of reference service, interlibrary loan, and circulation privileges. Teaching methods range from formal two-hour classes with hands-on exercises to informal shorter demonstrations. The use of a live Internet connection adds sophistication and flexibility to the presentations.

Whenever possible, continuing-education (CE) credit is arranged for participants. Applications are reviewed by professional organizations and the various CE departments at the University of Utah. CE has been offered to physicians, physician's assistants, nurses, dental hygienists, and dieticians. These classes are well received by practitioners in rural settings because no fee is charged; only a short travel distance is required; and classes are scheduled at their convenience.

Access to the Internet has resulted in a dramatic evolution of class content and presentation style in just a few short years. Once, a PowerPoint presentation explaining how to use the new online catalog and demonstrations of Grateful Med by modem were considered state-of-the-art and high tech. Now, content may include locating an Internet service provider (ISP), logging onto a proxy server, requesting an interlibrary loan electronically, evaluating Web sites, and accessing the table of contents of one of the library's books from an Internet bookstore. Laptop computers and LCD projectors are still standard equipment, but now ISP accounts are required as well. Small calling cards with the library's Web address and a disk with all the files in hypertext markup language (HTML) take the place of multicolored printed handouts. These files are also loaded on the library's server, so students can access them from home. Web pages are designed for special groups. An interactive Web-based class, “Internet Navigator” is also available for college credit.

The Outreach Web page* identifies patron categories and eligibility for services, highlights useful services, and provides links to electronic request forms and the online catalog of books. Another Web page designed by Eccles Library Knowledge Weaver staff permits fourth-year medical students in their primary care preceptorship (PCP) rotation to submit papers, clinical patient reports, and exams on the Web. The PCP students serve six weeks at rural rotation sites around the state. Twenty laptop computers, maintained by the library, are checked out to the students to use at rural sites. In a two-hour orientation session, the outreach librarian reviews use of electronic resources and proxy access to Web-based library materials, and familiarizes students with the laptops and Internet access.

From 1995 to 1997, the Eccles Library outreach program organized consecutive half-day “Information Access Workshops” at a small college for nursing students enrolled in traditional and distance-education courses. The content included search strategy, Internet searching, and acquiring materials after identification. Librarians from four institutions co-taught and introduced themselves to their respective students as the contact person for requesting library service.

The single most important facet of providing outreach services is the face-to-face contact the outreach librarian makes with rural providers. The providers and administrators know the librarian by name and face and, thus, know whom to call when they need help with information access. As a result, the librarian has gained a collective knowledge of patterns of staff and administrative turnover, budgetary constraints, and configuration of facilities for class presentations, and, most importantly, has developed personal relationships with individuals at each location. This underscores the admonition that not only must outreach librarians like to travel, but they also must enjoy meeting and serving people.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Initially, the outreach librarian was challenged to create a program without a travel or equipment budget. Eccles Library covered the librarian's salary, benefits, and attendance at professional meetings. Travel grants from the NN/LM—MR became available early in the project and paid for the needs assessment and travel to promote and teach Grateful Med. Support from the DOH also covered costs of equipment and travel. The UTN and the Utah AHECs reimbursed travel expenses for classes taught at their facilities. More recently, AHEC funding was used to cover the costs of interlibrary loans for distance-learning students to study future funding needs.

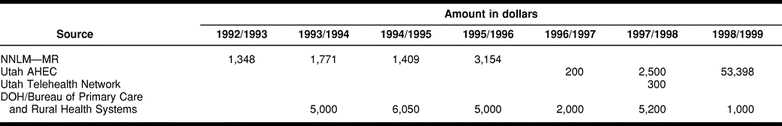

Eccles Library signed a contract with the Utah AHECs that provided support for the outreach librarian's salary and benefits, travel, library services, and overhead expenses for 1998/99. A shift from NN/LM funding to local sources, as indicated in Table 1 of funding sources since 1992, has affirmed the value of outreach services at the local level.

ADMINISTRATION

The outreach librarian oversees and carries out the three components of the outreach program, that to the UUHSC, to the Utah AHECs, and to the DOH. She reports to the director of the health sciences library. The outreach librarian and the three AHEC directors collaboratively make decisions regarding library services to the AHECs. The Eccles Library accounting department assists the outreach librarian in tracking grant expenditures. Yearly reports to the funding agencies, all due at different times, make statistics collection a challenge.

While the outreach librarian travels around the state, the outreach program involves and is integrated into the workload of the entire library staff. Calls or electronic requests for assistance in locating information from physicians in rural areas come to the reference department. Distance-learning students contact the interlibrary loan department by fax or electronically to request document delivery. The education librarian receives and forwards requests for classes from students living in remote areas.

Recalling and sharing humorous and touching stories help outreach librarians survive and cope with the rigors of travel and hard work.When first assessing needs in a focus group, one rural nurse admitted that if she were given the choice between an instant response digital thermometer and access to MEDLINE, she would choose the thermometer.A director of nursing in a small town excitedly reported that within a week of training, a black widow spider bite was successfully treated using information obtained from MEDLINE in a Grateful Med search.Several years ago, a hospital in a major tourist area of the state was in danger of closing due to the inability to recruit new physicians. The new administrator, in an attempt to satisfy the request of a physician who said he would move there if they had a library, asked for donations of books. Since that time the Eccles Library outreach program has donated newly weeded books from its collection to this hospital. The physician did come, in part because of the library. The administrator now boasts that they have the best collection of medical books in that region of the state. When asked if the books were being used, he proudly stated that they must be, because they were disappearing.

IMPLEMENTATION

In a circuit-rider approach, the outreach librarian fulfills the training responsibilities of the program. She travels the state, making trips lasting one to five days to visit multiple sites with a portable teaching workstation. An account with a Utah-based Internet service provider allows local-call Internet connections in nineteen locations around the state. The Utah State Motor Pool offers a reasonably priced rental-car service with four-wheel drive vehicles for trips during inclement weather or on unpaved roads. A cell phone provides added psychological security in case of an accident or problem on the road. With Utah's beautiful scenery, long trips are never boring. Support of locally owned motels injects a bit of adventure to a long trip, and who can resist knowing that “John Wayne slept here?”

Training takes place in a variety of settings from small clinics to larger hospitals. One demonstration was held in a break room where the display from the computer was projected onto a sheet tacked to the wall. The network connection cable was strung outside of one window, inside another, and from there to the computer. On another occasion, a class was held in a medical staff conference room that offered the latest technology. Recently, arrangements were made to teach in computer labs in rural high schools. This arrangement made it possible to teach the use of Web resources available to public libraries and schools on the statewide network. In the past, college library computer labs were used, but there were far more high schools with labs, thereby expanding the number of available training sites to offer hands-on training for larger groups.

It became apparent during trips from conversations overheard among health department employees that several of the rural clinics did not have computer equipment that could be used to search MEDLINE using the disk version of Grateful Med. Recycled or discarded computers and printers were acquired and placed in several rural clinics to be used to search Grateful Med. In most facilities, the value of access to information was recognized, and staff members were able to secure funding to upgrade this equipment. Very recently, however, a surprising request was made for additional discards to replace computers left more than six years ago.

In addition to transporting technology to the rural sites for use in presenting classes, at the University of Utah College of Pharmacy, newly installed technology, which permitted delivery of pharmacy updates electronically in real time, has been used. In the spring of 1998, the outreach librarian taught an hour-long class, “Internet for Pharmacists,” as part of an all-day workshop. The workshop was broadcast to pharmacists at rural sites over the statewide EDNET interactive video system located in high schools and colleges. Likewise, a focus group and information access trouble-shooting session for University of Utah College of Nursing graduate students was held over the UTN in the spring of 1999.

In response to a request by a rural physician for assistance in creating a medical library at his hospital, a pilot program is under way with the Central Utah AHEC to provide Web access to a database of full-text journal articles for professionals at three rural hospitals and clinics. The project will provide baseline data to determine the degree of support available for a statewide AHEC information access system for all hospitals and clinics in rural Utah.

The DOH promotes the Rural Medical Library Outreach Program in an irregularly published newsletter. As email has become more prevalent, it is the mode of choice for making arrangements and promoting services. The library's outreach Website promotes the program and provides links to categories of user services. In lieu of a separate publicity effort, the librarian has worked hard to develop partnerships where library services are accepted and promoted as an integral part of another group's services.

RESULTS AND IMPACT

Because of the large size of the population served in the program, no comprehensive survey has been sent to all the participants. Evaluation forms are distributed after each class. The responses to these forms have been extremely positive. When asked about the program's contribution to the improvement of health care, comments focus on the newness of the material and on amazement as to the wealth of available information. Evaluation results clearly indicate attendees consider the information will be valuable to them for patient treatment.

Because the goal of training is to reach as many rural health professionals as possible, anyone who wishes may attend classes. Proof of affiliation with one of the service areas becomes unnecessary. Rural nurses often work and take classes toward a degree. One individual, therefore, may qualify for training as a student in training supported by the AHEC, as a University of Utah student, and as an employee of a clinic with affiliations and served by the DOH. Data collected about the professionals show that the highest number of participants are nurses with physicians, pharmacists, and public health staff following in that order.

A survey of nursing students who attended the “Information Access Workshops” found that the skills they learned and used as a result of having attended the workshops, over a six-month period, saved them twenty-six trips to Salt Lake City to use the library. Those twenty-six trips represented an average of 250 miles per trip, saving 7,250 miles and 120 hours in travel time.

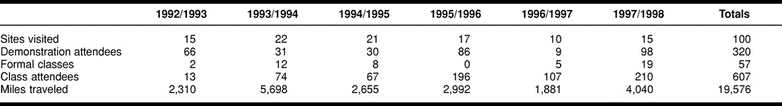

In a formal continuing-education survey performed by the AHEC program office Outreach Committee, learning about computers and information access has been identified as one of the top-ten needs. An increase over the years in the numbers of professionals trained, as outlined in Table 2, indicates the program is addressing a need identified by the Utah AHEC.

These outreach efforts have not gone unrecognized by outside groups. The efforts of the outreach program contributed in part to the Utah Medical Association awarding Eccles Library their first Presidential Citation on September 9, 1998, “in recognition of invaluable support of the physicians of Utah in the application of information technology to improve the practice of medicine.” Also, the outreach librarian received the Friends of the National Library of Medicine's Seventh Michael E. DeBakey Library Services Outreach Award for her efforts as the coordinator of this program.

THE FUTURE

The Eccles Library remains committed to outreach as an important service goal. Travel to rural clinics and hospitals to teach information-access skills will undoubtedly continue. One new direction involves a shift to increased Web design to take advantage of the library's in-house resources. Staff of the Knowledge Weaver project† provide a wealth of multimedia expertise. Plans are underway to collaborate with the DOH on a project to develop online searching tutorials that interface with public health training and curricula, thereby freeing rural staff from long-distance travel for training.

There is no evidence that the Digital Divide will soon be closed. There is, however, an excellent opportunity for the Utah AHECs to take the lead in advocating for rural hospitals and clinics with regard to access to training and electronic information resources. The library is dedicated to working with the AHECs and their other partners to accomplish this goal.

Table 1 Sources of finding for Eccles Library Outreach Program from 1992–1999

Table 2 Training statistics for Eccles Library Outreach Program, 1992–1998

Footnotes

* The Outreach Web page is available at http://medlib.med.utah.edu/outreach/indexout.htm.

† Information about the Knowledge Weaver project is available at http://medstat.med.utah.edu/kw/.

REFERENCES

- Office of the Press Secretary. From digital divide to digital opportunity a national call to action, Apr 4, 2000. [Web document]. Washington, DC: The White House. [cited Apr 24 2000]. <http://www.pub.whitehouse.gov/uri-res/I2R?urn:pdi://oma.eop.gov.us/2000/4/5/5.text.1>. [Google Scholar]

- Barton M. ed. . Data section I: Utah's demographic characteristics. In: Utah's health: an annual review. v. 5. Salt Lake City, UT: Governor Scott M. Matheson Center for Health Care Studies, University of Utah. 1997–98 71. [Google Scholar]

- State population estimates: annual time series, July 1, 1990 to July 1, 1999. [Web document]. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census. [rev. Dec 29, 1999; cited Apr 21, 2000]. <http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/state/st-99-3.txt>. [Google Scholar]

- Barton M. ed. . Data section I: Utah's demographic characteristics. In: Utah's health: an annual review. v. 5. Salt Lake City, UT: Governor Scott M. Matheson Center for Health Care Studies, University of Utah. , 130. [Google Scholar]