Abstract

The structure of temperament traits in young children has been the subject of extensive debate, with separate models proposing different trait dimensions. This research has relied almost exclusively on parent-report measures. The present study used an alternative approach, a laboratory observational measure, to explore the structure of temperament in preschoolers. A 2-stage factor analytic approach, exploratory factor analyses (n = 274) followed by confirmatory factor analyses (n = 276), was used. We retrieved an adequately fitting model that consisted of 5 dimensions: Sociability, Positive Affect/Interest, Dysphoria, Fear/Inhibition, and Constraint versus Impulsivity. This solution overlaps with, but is also distinct from, the major models derived from parent-report measures.

Keywords: temperament, preschoolers, laboratory observational measure

A number of rich theoretical traditions have emerged from the developmental literature to describe the nature and structure of early appearing individual differences in temperament (i.e., Thomas & Chess, 1977; Buss & Plomin, 1984; Rothbart, 1981). More recently, developmental researchers have examined the applicability of the Five Factor Model (FFM; Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993; McCrae & Costa, 1987) of adult personality to young children (e.g., Abe, 2005; Kohnstamm, Halverson, Mervielde, & Havil, 1998; Halverson et al., 2003; Lamb, Chung, Wessels, Broberg, and Hwang, 2002). Although most of these research traditions concur that the structure of temperament traits in preschool-aged children is multidimensional, there is little consensus regarding the number and nature of these primary dimensions (De Pauw, Mervielde & Leeuwan, 2009; De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010). Furthermore, across all of these traditions, investigations of the structure of child temperament traits has relied almost exclusively on parent report measures of these constructs. Given the low convergence across different methods of assessing temperament (Goldsmith & Campos, 1990; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Hershey, 2000), it is plausible that the trait structure recovered from alternative measurement approaches may differ. In the present study, we used another approach, a laboratory-based observational measure, to examine the structure of traits in preschool-aged children.

Multidimensional Models of Temperament in Preschool-Aged Children

Current conceptualizations of child temperament draw from one or more of three major models of child temperament (Thomas & Chess, 1977; Buss & Plomin,1984; Rothbart, 1981). While other influential models have been proposed (e.g., Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987), these have generally focused on a smaller number of rather narrowly defined traits, rather than focusing on broadband dimensions of temperament.

Thomas and Chess

Based on the infancy period of their longitudinal study, Thomas and Chess postulated a model consisting of nine bipolar temperament dimensions that they believed were stable across development from infancy to adulthood (Thomas & Chess, 1977). The dimensions were labeled Activity (physical energy), Approach/Withdrawal [initial reaction or response to novelty, conceptually similar to Kagan’s (1994) Behavioral Inhibition/Disinhibition], Adaptability (the amount of time required to adjust to change in the environment), Mood (a general tendency toward positive or negative demeanor), Threshold of Responsiveness/Sensitivity (the amount of stimulation necessary to induce a reaction), Intensity of Reaction (energy level of positive or negative response), Distractibility (tendency of the child to be diverted by external stimuli), Rhythmicity/Regularity (predictability of the child’s biological functions or behavior), and Attention Span/Task Persistence (the ability to stay on task when challenged or frustrated). However, factor analytic studies of the parent and teacher versions of the Temperament Assessment Battery for Children (TABC; Martin, 1988), which was developed within Thomas and Chess’ framework, failed to support the nine-dimension model (Presley & Martin, 1994; Martin, Wisenbaker, & Huttunen, 1994). Results from Presley and Martin’s (1994) factor analysis revealed that a five-factor solution consisting of Negative Emotionality, Social Inhibition, Agreeableness/Adaptability, Task Persistence, and Activity Level was most appropriate for parent ratings of three- to seven-year-old children. They also noted that Activity Level had strong associations with both positive and negative affect in early development, suggesting it may not represent an independent dimension.

Buss and Plomin

As an alternative to the Thomas and Chess model, Buss and Plomin (1975, 1984) initially proposed a model consisting of the four temperament dimension of Emotionality (intensity of emotion), Activity (amount of physical energy), Sociability (closeness to others), and Impulsivity (quickness, disinhibition). Subsequently, they dropped Impulsivity because factor analytic studies revealed that it comprised multiple subtraits, most of which failed to replicate (Buss & Plomin, 1975; Zentner & Bates, 2008).

Rothbart

Rothbart and colleagues (e.g., Rothbart, 1981; Rothbart & Ahadi, 1994; Rothbart & Bates, 2006) define temperament as constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity (physiological excitability and responsiveness to change in both the internal and external environment) and self-regulation (processes that modulate reactivity). This model was initially developed for infants, but subsequent work extended it to older children and resulted in the creation of a series of age-specific parent-report measures, including the Infant Behavior Questionnaire (3–12 months of age) (IBQ; Rothbart, 1981), the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (18–36 months of age) (ECBQ; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006), the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (3–7 years) (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001), the Temperament in Middle Children Questionnaire (7–10 years) (TMCQ; Simonds & Rothbart, 2004), and the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (9–15 years) (EATQ; Capaldi & Rothbart, 1992), each of which has a number of primary scales. Rothbart and colleagues have also devised a self-report measure for adults: the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ; Evans & Rothbart, 2007). Factor analytic studies of the primary scales across age groups have consistently yielded three broad temperament dimensions: Extraversion/Surgency (motor activity, high intensity pleasure, and sociability), Negative Affectivity (anger, fear of novelty, sadness, low soothability), and Effortful Control (attentional focusing and shifting, inhibitory control, and perceptual sensitivity) (Rothbart et al., 2001). The dimensions of Extraversion/Surgency and Negative Affectivity encompass the components of the underlying reactivity process, whereas Effortful Control reflects behavioral constraint and self-regulation processes.

Adult Personality Structure Applied to Preschool-Aged Children

The models reviewed above were developed using a “bottom up” approach, by identifying dimensions of individual differences in behavior most salient in youngsters or by considering the development of mechanisms relevant to emotional and social behavior, such as regulatory processes. A contrasting approach is to explore whether models of adult personality can be extended to describe child temperament traits.

Five-Factor Model

The Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality has acquired widespread support as a comprehensive higher-order taxonomy of personality for adults across genders, cultures, and methods (e.g., Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993; McCrae & Costa, 1987). This model consists of five bipolar dimensions labeled Extraversion (sociability, positive affect, and reward-seeking), Neuroticism (anxiety, sadness, fear, emotional instability), Conscientiousness (carefulness, self-discipline, planfulness, and reliability), Agreeableness (warmth, generosity, cooperation with others), and Openness to Experience (imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, intellectual curiosity).

A growing number of developmental psychologists have begun to examine the validity of the FFM for understanding personality traits in youth. The five-factor structure has been recovered in older children and adolescents based on parent-reports (e.g., Barbaranelli, Caprara, Rabasca, & Pastorelli, 2003; John, Caspi, Robins, Moffit, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 1994; Mervielde & De Fruyt, 1999), teacher-reports (e.g., Barbaranelli et al., 2003; Digman & Inouye, 1986; Digman & Shymelov, 1996; Goldberg, 2001; Graziano & Ward, 1992; Mervielde, Buyst, & De Fruyt, 1995), and self-reports (e.g., Barbaranelli et al., 2003; De Fruyt, Mervielde, Hoekstra, & Roland, 2000; Markey, Markey, Tinsley, & Erikson, 2002). More recently, developmental researchers have started to examine the utility of this model in even younger children. Factor analytic studies have extracted the FFM dimensions in samples of preschool-aged children using two parent-report measures, the Inventory of Childhood Individual Differences (ICID; Halverson et al., 2003; Zupancic, Podlesek, & Kavcic, 2006) and the California Child Q-sort (CCQ; Abe, 2005; Abe & Izard, 1999; Lamb et al., 2002). Additionally, child self-reported traits measured longitudinally with the Berkley Puppet Interview from ages of six to seven years have also provided support for the five-factor structure in young children (Measelle, John, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 2005).

However, support for the FFM has been less consistent with early childhood samples than with older youth and adults. For instance, several studies have reported limited internal consistency of parent and self-report measures of some of the FFM traits in young children (Lamb et al., 2003; Measelle et al., 2005). Thus, it is possible that these traits do not fully coalesce until later in development. Moreover, several factor analytic studies using preschool-aged samples have reported factor structures that deviate from the FFM. Specifically, some have found additional traits (e.g., irritability), which are associated with, but separate from, the FFM dimensions (e.g., Abe & Izard, 1999; De Pauw et al., 2009; Lamb et al., 2002). In addition, others have failed to retrieve all of the FFM dimensions (e.g., Mervielde, Buyust, & De Fruyt, 1995 did not recover an Openness factor). These inconsistent findings may be a reflection of the different ways in which these traits are defined and measured across studies (Caspi & Shiner, 2006). Moreover, a certain degree of cognitive and social development may be necessary before some traits can emerge. Therefore, further study with preschool-aged samples is necessary to elucidate differences in the developmental manifestations of the FFM traits (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; De Pauw et al., 2009).

Common Dimensions of Temperament Across Models

The growing consensus about the structure of adult personality has prompted developmental researchers to create a unified taxonomy for the structure of child temperament. Accordingly, Mervielde and Asendorpf (2000) have identified the dimensions that are shared by Thomas and Chess’ (1977), Buss and Plomin’s (1984), and Rothbart’s (1981) models. They argued that four dimensions are required to encapsulate the components of these three models: Emotionality, Extraversion, Activity, and Persistence (see De Pauw et al., 2009 and De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010 for more detailed reviews). Caspi and Shiner (2006) have also proposed a common taxonomy for temperament and personality which encompasses traits from the preschool years into adulthood. This hierarchical model contains five higher order dimensions using the FFM labels of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Openness to Experience. Each of these higher-order traits incorporates and explains the covariation among the lower-order traits, which include many of the narrower traits from the various child temperament models.

Rationale for the Present Study

Factor analytic studies examining the structure of traits in preschool-aged children have predominantly relied on parent-reports (Abe & Izard, 1999; Abe, 2005; Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Halverson et al., 2003; Lamb et al., 2003; Presley & Martin, 1994; Rothbart et al., 2001; Zentner & Bates, 2008). In addition to being time-efficient and economical, parent-report measures draw upon a parent’s vast history and knowledge of his or her child’s behavioral and emotional reactions across a variety of different contexts (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). However, parent-report measures are susceptible to a number of perceptual and response biases, and, as a result, reflect a blend of objective and subjective influences (Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Stifter, Willoughby, & Towe-Goodman, 2008). For example, parents may respond according to their own emotional state or their responses may reflect implicit assumptions about temperament structure. As such, the validity of parent-report measures has been questioned by some developmental researchers (e.g., Kagan, 1998).

Although more time-intensive and expensive, laboratory observational measures of child temperament have several distinct advantages compared with parent-report measures. Laboratory measures use standardized procedures that can be controlled by the researcher to elicit specific emotions and behaviors of interest (Majdandzic & van den Boom, 2007; Zeman, Klimes-Dougan, Cassano, & Adrian, 2007). Additionally, despite being based on limited samples of behavior, observational measures use objective criteria to code emotion and behavior, precluding variation attributable to parent’s interpretations and biases.

Rothbart and Goldsmith (1985) argued that high convergence between parent report and laboratory observation measures should not be expected, as each has its own advantages and limitations. Indeed, studies have consistently reported that the associations between parent-report and observational measures of temperament are relatively low (e.g., Durbin, Hayden, Klein, Olino, 2007; Majdandzic, & van den Boom, 2007).

In light of the differences between observational and parent-report measures, it is plausible that laboratory observations will yield a different structure and unique perspective on temperament in preschoolers compared with parent-report measures. Accordingly, we sought to address this gap in the literature by using a laboratory observational measure [the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB), Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1995] to examine the structure of traits in preschool-aged children. Although we did not have strong hypotheses, we expected some broad similarities between our model and those derived from parent-report measures. For example, given the ubiquity of higher-order traits resembling Extraversion/Positive Emotionality, Neuroticism/Negative Emotionality, and Constraint/Persistence/Effortful Control in the temperament and personality literatures (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010; Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005), we anticipated finding dimensions reflecting these constructs.

Because of the somewhat exploratory nature of the study, we used a two-stage factor analytic approach. First, based on the longstanding tradition within the field of personality/temperament research, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to obtain a preliminary structure. Subsequently, the structure recovered from the EFA was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in an independent sample. The use of CFA to test models of personality/temperament has been controversial (e.g., Church & Burke, 1994; Hopwood & Donnellan, 2010; Marsh et al., 2010; McCrae, Zonderman, Costa, Bond, & Paunonen, 1996). Temperament/personality data are complex, and cross-loadings and correlated residuals between lower order scales are common. The CFA approach often fails to account for these types of relations, by constraining nontarget loadings to zero and assuming that that each item loads on one factor, which can lead to misspecifications or distortions in the structural relations among different items and factors (Church & Burke, 1994; Hopwood & Donnellan, 2010; Marsh et al., 2009; McCrae et al., 1996). There is also debate regarding the use of “absolute cutoffs” for goodness-of-fit indices in CFA. Recently, personality researchers have argued that currently accepted criteria/cutoffs are inappropriately restrictive for evaluating the structure of temperament/personality traits (Hopwood & Donnellan, 2010; Marsh et al., 2010). Hence, we followed their recommendations in applying CFA procedures to our temperament data.

Method

Participants

Recruitment

The sample included 559 children (54.0% male and 46.0% female) from Long Island, NY who lived with at least one English-speaking biological parent. The mean age of the children was 42.2 months (SD = 3.1). Children with significant medical conditions or developmental disabilities were excluded. Participants were recruited through commercial mailing lists. Of eligible families, 69.1% entered the study and completed the laboratory temperament assessment. Following a detailed description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all the families. The families were financially compensated for their participation.

Demographics

The sample was primarily White/European American (87.1%) and middle class, as measured by the Hollingshead’s Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975; M = 54.2; SD = 11). The mean ages of the mothers and fathers were 36.0 (SD = 4.4) and 38.3 years (SD = 5.4), respectively. The majority (94.2%) of the children came from two-parent homes, and 51.4% of the mothers worked outside of the home part- or full-time. 55.0% of the mothers and 47.0% of the fathers had a college degree or higher.

Assessment Procedures

Laboratory assessment

The laboratory assessment lasted approximately two hours and included a standardized set of 11 laboratory episodes adopted from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab TAB; Goldsmith et al., 1995) and one episode (Exploring New Objects) designed for this study. The Lab-TAB provides standardized episodes designed to elicit a variety of emotions and behaviors (see descriptions below) and can be scored at varying “grain” levels (e.g., global and microlevel coding, described below) (Gagne, Van Hulle, Aksan, Essex, & Goldsmith, 2011). Most of the episodes in the Lab-TAB were drawn from previous studies examining child social and personality development and thus have a history of successful usage in developmental psychology (Goldsmith et al., 1995). There was a short play break between episodes that allowed the children to return to a neutral affective state. All of the episodes were videotaped through a one-way mirror and later coded. A parent remained in the room for all episodes except for Stranger Approach and Box Empty. Below is a description of each episode:

Risk room

The child was left alone to explore a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including a large black box with eyes and teeth, a cloth tunnel, a Halloween mask, balance beam, and small staircase. After five minutes, the experimenter returned to the room and asked the child to engage in play with each object. This Lab-TAB episode was derived from a series of studies of behavioral inhibition by Kagan and colleagues (e.g., Kagan, 1998; Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1986).

Tower of patience

The child and experimenter alternated turns building a tower together with large blocks. During each turn, the experimenter increased delays in placing the block on the tower, making the child wait. This Lab-TAB episode, like some of the other episodes tapping impulsive behavior, was derived from prior research by Kochanska and colleagues (Kochanska, Murray, Jacques, Koenig, & Vandegeest, 1996).

Arc of toys

The child was allowed to play freely by him/herself in a room with toys for a few minutes, after which the experimenter returned and asked the child to clean up the toys.

Stranger

The child was briefly left alone in the empty assessment room while the experimenter went to look for other toys. In the experimenter’s absence, a male research assistant entered the room and spoke to the child in a neutral tone while gradually walking closer to the child.

Car go

The child and experimenter raced remotely controlled cars.

Transparent box

The child selected a toy, which was then locked in a transparent box. The child was then left alone in the room with a set of incorrect keys to use to open the box.

Exploring new objects

The child was left alone to explore a set of novel and ambiguous stimuli, including pretend mice in a cage, sticky water-filled gel balls, a mechanical bird, a mechanical spider, and a pretend skull covered under a blanket. After five minutes, the experimenter returned and asked the child to play with each object.

Pop-up snakes

The experimenter showed the child what appeared to be a can of potato chips, which actually contained coiled spring “snakes.” The experimenter then encouraged the child to surprise the child’s parent with the can of snakes.

Impossibly perfect green circles

The child was instructed to repeatedly draw a circle on a large piece of paper. After each drawing, the circle was mildly criticized.

Popping bubbles

The child and experimenter played with a bubble-shooting toy.

Snack delay

The child was instructed to wait for the experimenter to ring a bell before eating a snack. The experimenter systematically delayed ringing the bell.

Box empty

The child was given a box to unwrap, but rather than containing a present, the box was empty.

Laboratory coding procedures

We selected constructs based on the literature on the structure of temperament/personality in youth (e.g., Caspi & Shiner, 2006; De Pauw et al., 2009; De Pauw & Mervielde, 2010) and attempted to include all constructs that could be coded using laboratory observations. Coding schemes were selected from existing coding systems (e.g., Carlson, 2005; Durbin et al., 2007; Goldsmith et al., 1995; Kagan et al., 1984). Constructs that were not represented in existing coding systems were scored using a global coding approach (see below). Different coding methods were used for the affective, behavioral, behavioral inhibition (BI), and inhibitory control variables. For almost all variables, we combined ratings across episodes to create cross-situational indices and reduce the impact of episode-specific influences. The episodes were coded by undergraduate research assistants, study staff, and graduate students who completed extensive training and were unaware of other study variables. Coders were assigned to specific episodes and had to reach at least 80% agreement on all specific codes within the episode with a “master” rater before coding independently. To examine interrater reliability, videotapes of 35 children were independently coded by a second rater (only eight children were used to assess interrater reliability of Inhibitory Control because it uses simple count variables). To calculate the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), a two-way random, absolute agreement interrater ICC was used (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). We also examined the internal consistency of the scales using coefficient alpha based on the entire sample (n = 559).

Affective traits

Each instance (i.e., time stamp recorded) of facial, bodily, and vocal positive affect, anger, sadness, and fear were rated on a three-point scale (low intensity, moderate intensity, high intensity) during all 12 episodes. Within each episode, these intensity ratings were summed within each channel (facial, bodily, vocal) (e.g., sum of low, moderate, and high facial affect in the Risk Room episode), which produced 36 scores (facial affect for 12 episodes, bodily affect for 12 episodes, vocal affect for 12 episodes) for each of the four affective traits. The intensity ratings were then averaged within each channel across all 12 episodes (e.g., we computed the mean of the sum of low, moderate, and high facial PA in Risk Room + the mean of the sum of low, moderate, and high facial PA in Tower; etc.), which resulted in scores for each of the three channels for each of the four affective traits. Each of these 12 variables was then standardized (e.g., we standardized the mean of the sum of the facial PA intensity scores across all episodes, standardized the mean of the sum of the bodily PA intensity scores across all episodes, and standardized the mean of the sum of vocal PA intensity scores across all episodes). This resulted in a standardized score for each channel for each affective trait. Finally, the standardized scores for the three channels were then averaged for each affect [e.g., PA = (standardized facial PA + standardized bodily PA + standardized vocal PA)/3]. Coefficient alpha for the positive affect (PA), anger, sadness, and fear scales were .87, .68, .81, and .63, respectively. Interrater ICCs (n = 35) for PA, sadness, anger, and fear were .92, .79, .73, and .64, respectively.

Other behavioral traits

Global ratings of the behavioral trait variables were derived using all of the relevant behaviors during that episode. The following variables were rated on a single four-point Likert scale (0 = low, 1 = moderate, 2 = moderate to high, and 3 = high): Interest (α = .68, ICC = .84) was based on how engaged the child appeared in play. Anticipatory PA (α = .70, ICC = .63) was based on PA that occurred in anticipation of a reward, reinforcer, or positive event. Initiative (α = .74, ICC = .70) was based on the degree of passivity or assertiveness the child displayed in their interactions with others. Activity (α = .73, ICC = .75) was based on movement during each episode as well as the amount of vigor exhibited in the manipulation of the stimuli. Sociability (α = .83, ICC = .83) was based on the child’s attempts to engage and interact with the experimenter and the parent. Compliance (α = .77, ICC = .85) was based on the severity of “rule-breaking,” the persistence of the noncompliance, and the degree to which these behaviors were judged to reflect an intentional unwillingness to comply with the experimenter’s or parent’s suggestions, requests, or demands. Impulsivity (α = .70, ICC = .75) was based on the child’s tendency to act or respond without reflection or hesitation.

The following variables were rated on the degree to which the child exhibited the behavior during the episode (0 = none, 1 = slightly, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much): Assertiveness (α = .69, ICC = .59) was based on the degree to which the child made requests or demands, offered suggestions, or drew attention to him/herself. Pushy (α = .70, ICC = .87) was based on the degree to which the child made demands, was actively noncompliant, and argued with the experimenter or mother. Hostility (α = .60, ICC = .84) was based on the degree to which the child directed physical or verbal aggression or angry comments at the experimenter or mother. Clingy (α = .70, ICC = .51) was based on the degree of clingy behavior, proximity-seeking, and reassurance-seeking directed at the experimenter or parent, and needing the experimenter or parent to participate in order to play. Lastly, social anxiousness (α = .50, ICC = .62) was based on the degree of nervous smiling, sad response to criticism, and submissive behavior.

Dominance versus submissiveness and warmth versus hostility were rated on a 11-point Likert scale [−5 (extremely negative) to 5 (extremely positive)] because these traits are bivalent. Dominance (α = .76, ICC = .59) was based on the degree of social potency demonstrated by the child in the interaction. High scores reflected high levels of dominant behavior, whereas negative scores indicated submissiveness and passivity. Warmth (α = .79, ICC = .77) was based on the degree of warmth or affiliation the child displayed in the interaction. Thus, high scores were indicative of high levels of warmth and affiliation, whereas negative scores were indicative of interpersonal hostility.

Behavioral inhibition (BI)

BI refers to reactions of fearfulness, wariness, and low approach to unfamiliar people, objects, and contexts (Kagan, Reznick, Clarke, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984). The Risk Room, Stranger Approach, and Exploring New Objects episodes were coded using Goldsmith et al.’s (1995) system, which, consistent with most of the literature on BI, involves making highly specific ratings of behavioral responses at discrete time intervals (20–30 second epochs). For the present study, the BI variable did not contain any affective ratings from the Risk Room, Stranger Approach, and Exploring New Object episodes because the affective ratings were used to create the fear variable described above. The BI composite variable (α = .74, interrater ICC = .90) was constructed by combining the average standardized ratings of the following variables from the Risk Room (RR), Stranger, and Exploring New Objects (ENO) episodes: total number of objects touched (RR and ENO only), latency to touch objects (RR and ENO only), tentative play (RR and ENO only), referencing experimenter (RR and ENO only), time spent playing (RR and ENO only), latency to vocalize, approach toward the stranger (Stranger only), avoidance of the stranger (Stranger only), gaze aversion (Stranger only), and verbal/nonverbal interaction with the stranger (Stranger only). Variables were all keyed in a consistent direction (e.g., long latencies to touch objects were keyed to reflect more BI).

Inhibitory control

The Tower of Patience and Snack Delay episodes were each coded for inhibitory control using a coding system adapted from Carlson (2005), which involved tallying the number of times a child failed to wait his or her turn during the episode. Tower of Patience consisted of 14 trials and Snack Delay consisted of seven trials. The composite global inhibitory control variable (α = .70, interrater ICC = .98) was constructed by standardizing each score and then aggregating the scores from the two episodes.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Nine participants were excluded because of missing data, resulting in a sample of 550 participants with complete data. A number of the variables were transformed to reduce skewness and kurtosis. A square root transformation was applied to the PA variable. Log transformations were applied to the sadness, fear, impulsivity, clingy, hostility, pushy, socially anxious, and inhibitory control variables. All variables were then standardized. Lastly, the sample was randomly divided into two subsamples, the exploratory factor analysis sample (n = 274) and the confirmatory factor analysis sample (n = 276). The two samples were similar on gender and the variables of interest in this study.

Exploratory Factor Analyses

Principal axis factor analysis (EFA) with a Promax rotation was conducted on 20 variables from the LabTAB (see Table 1). The utility of the EFA factor solution was evaluated against the following criteria for factor retention: (a) eigenvalue >1.00 rule (Kaiser-Guttman criterion); (b) scree test (Gorsuch, 1983); (c) the configuration accounted for at least 50% of the total variance (Streiner, 1994); and (d) at least three variables per factor, as required to identify common factors (Anderson & Rubin, 1956; Comrey, 1988). We considered variables meaningful when their factor loadings exceeded .30 (Floyd & Wildman, 1995). Based on these criteria, a five-factor solution that accounted for 73.9% of the total variance was retained. Factors were named based on the items that loaded on them: I (Sociability; EV = 6.26), II (PA/Interest; EV = 4.23), III (Dysphoria; EV = 1.85), IV (Fear/Inhibition; EV = 1.26) and V (Constraint vs. Impulsivity; EV = 1.17). Factors I (Sociability), II (PA/Interest), and IV (Fear/Inhibition) all achieved a clear structure with all factor loadings above .40. Factors II (PA/Interest) and V (Constraint vs. Impulsivity) were slightly less clear because of the high cross loading of the activity level variable on both factors. This is not surprising because some models of temperament include activity level as part of an Extraversion/Surgency/PA factor (e.g., Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Kochanska, Aksan, Penney, & Doobay, 2007; Rothbart et al., 2001), whereas other models view activity level as closely linked to high impulsivity (Abe, 2005; Buss, Block, & Block, 1980; Dickman, 1990; Prior, 1992; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Again, all factors loadings (with the exception of activity level on factor V) were above .40.

Table 1.

Exploratory Factor Analysis With All Lab-TAB Variables

| Lab-TAB variable | Sociability | PA/Interest | Dysphoria | Fear/Inhibition | Constraint versus Impulsivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiative | .92 | −.01 | .03 | −.05 | .01 |

| Sociability | .91 | .14 | −.08 | .17 | −.18 |

| Dominance | .85 | .04 | .15 | −.03 | .05 |

| Assertiveness | .85 | −.01 | .21 | .09 | −.08 |

| Socially Anxious | −.74 | .26 | .23 | .09 | −.18 |

| PA | −.09 | .99 | .15 | .12 | .04 |

| Anticipatory PA | −.22 | .99 | .17 | .05 | .07 |

| Interest | .21 | .69 | −.15 | −.15 | −.09 |

| Warmth | .24 | .64 | −.38 | .04 | −.18 |

| Activity | .28 | .51 | −.02 | −.12 | .39 |

| Anger | .05 | −.01 | .93 | −.10 | −.17 |

| Hostility | −.13 | .17 | .90 | −.11 | −.05 |

| Sadness | .00 | .02 | .86 | .14 | −.30 |

| Pushy | .21 | −.04 | .63 | .05 | .21 |

| BI | −.21 | .13 | −.13 | .84 | .14 |

| Fear | .30 | −.04 | −.05 | .84 | −.09 |

| Clingy | −.01 | .03 | .15 | .68 | .15 |

| Inhibitory Control | −.05 | −.01 | −.33 | .12 | .93 |

| Impulsivity | .10 | .27 | .15 | −.09 | .67 |

| Compliance | −.21 | .28 | −.29 | −.10 | −.53 |

Note. Items with highest loading on each factor are in bold.

To create a more parsimonious model to be tested with confirmatory factor analysis in the second subsample, we selected three variables per factor, for a total of 15 variables. The variables were chosen based on the following criteria: (a) variables with the highest loadings on the factor; (b) favorable distributional characteristics (i.e., limited skewness/kurtosis); and (c) low correlations with variables on other factors (i.e., discriminant validity). To verify that we could obtain a similar structure with this reduced variable set, an EFA with a Promax rotation was repeated with the 15 selected variables. The same five-factors were retained using the aforementioned criteria (see Table 2). More specifically, Factor I (Sociability; EV = 4.32) included the variables sociability, initiative, and dominance; Factor II (Dysphoria; EV = 3.19) included anger, hostility, and sadness; Factor III (PA/Interest; EV = 1.71) included positive affect (PA), anticipatory PA, and interest; Factor IV (Fear/Inhibition; EV = 1.12) included fear, BI, and clingy; and Factor V (Constraint vs. Impulsivity; EV = 1.09) included impulsivity, compliance, and inhibitory control. This five-factor solution accounted for 76.2% of the total variance.

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis With 3 Lab-TAB Variables per Factor (15 Variables Total)

| Lab-TAB variable | Sociability | Dysphoria | PA/Interest | Fear/Inhibition | Constraint versus Impulsivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociability | .95 | −.07 | .08 | .13 | −.13 |

| Initiative | .94 | .01 | −.05 | −.05 | .07 |

| Dominance | .83 | .13 | .02 | −.04 | .13 |

| Anticipatory PA | −.11 | .11 | .96 | .05 | .09 |

| PA | .05 | .08 | .92 | .12 | .02 |

| Interest | .35 | −.20 | .61 | −.15 | −.12 |

| Anger | .07 | .91 | −.03 | −.08 | −.11 |

| Hostility | −.11 | .88 | .16 | −.09 | .02 |

| Sadness | .02 | .80 | .00 | .16 | −.19 |

| Fear | .35 | −.06 | −.09 | .85 | −.12 |

| BI | −.21 | −.10 | .15 | .83 | .08 |

| Clingy | −.11 | .19 | .05 | .68 | .11 |

| Inhibitory Control | −.08 | −.29 | .26 | −.10 | .97 |

| Impulsivity | .18 | .13 | .23 | −.11 | .65 |

| Compliance | −.18 | −.29 | .26 | −.09 | −.56 |

Note. Items with highest loading on each factor are in bold.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The next step was to conduct a CFA with maximum-likelihood estimation procedures with the second subsample (n = 276) to cross-validate the five-factor structure obtained using EFA in the first subsample (n = 274). To assess model fit, we used the following: (a) the chi-square statistic; (b) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990); and (c) the root-mean-square error (RMSEA; Steiger & Lind, 1980). Chi-square is often significant in moderate and large samples, hence it is given less weight than the other indices. In light of recent discussions of the use of CFA in personality/temperament research (e.g., Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004; Marsh et al., 2010), we followed Hopwood and Donnellan’s (2010) recommended cutoff values of CFI > .90 and RMSEA < .10 to indicate acceptable model fit.

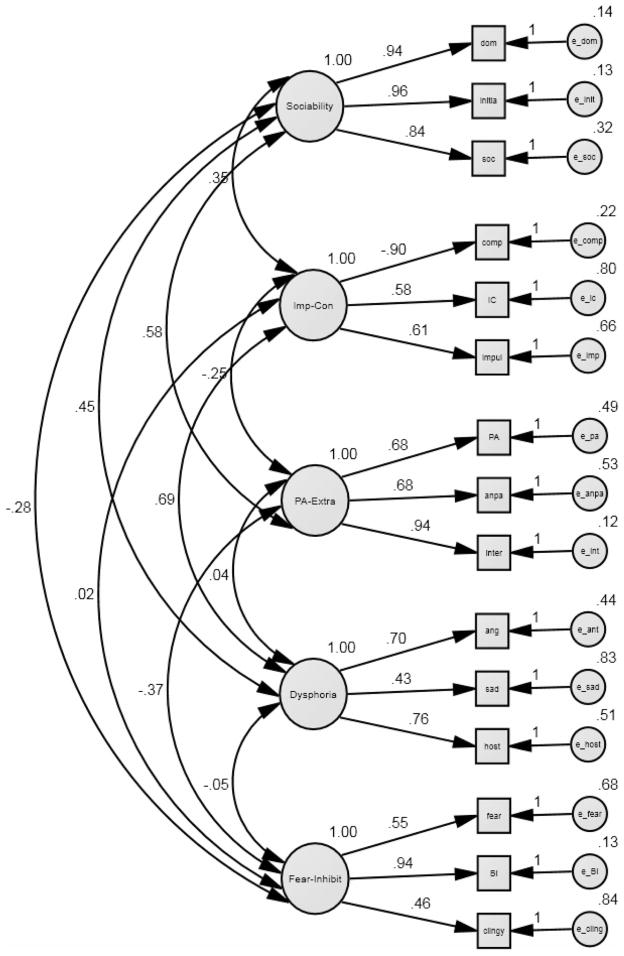

The variances of the five latent factors were fixed to 1.0 to obtain significance values for all of the paths. Our target model was the hypothesized five-factor, 15-variable model (see Figure 1). Fit indices from this model are presented in Table 3. The model was a poor fit to the data, RMSEA = .141 (CI = .130–.153), CFI = .791.

Figure 1.

Original CFA model.

Table 3.

Summary of Fit Indices for Lab-TAB Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | CI RMSEA (Lo 90–High 90) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original model | 517.333*** | 80 | .797 | .141 | .130–.153 |

| Modified model | 242.575*** | 79 | .924 | .087 | .074–.099 |

Note. df = degrees of freedom; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; CI RMSEA = 90% confidence interval for root-mean-square of approximation.

p < .001.

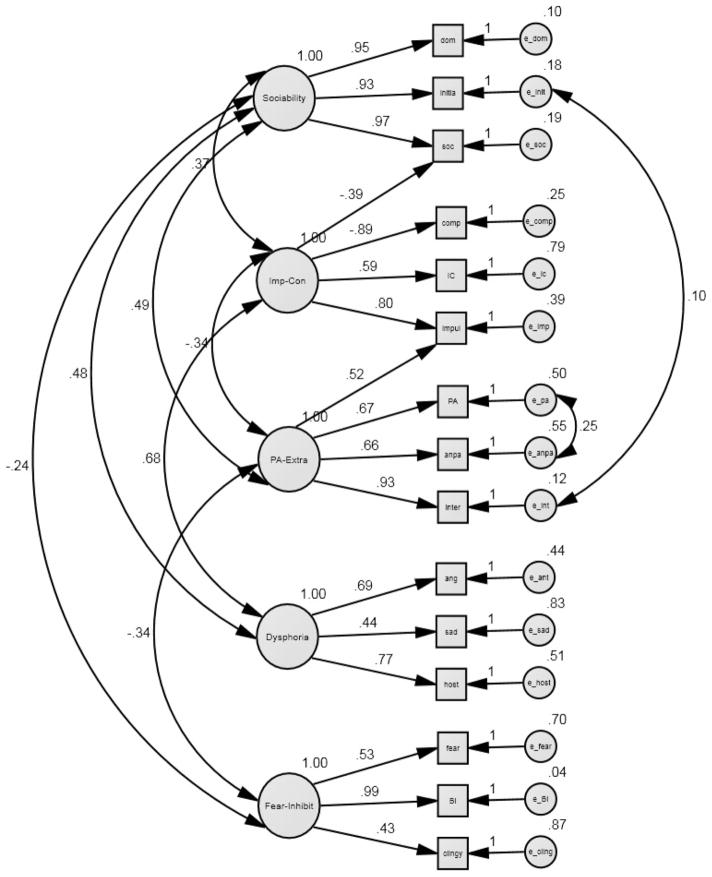

Post Hoc Model Fitting

To improve the CFA model fit, we examined the model estimates and modification indices (MIs). The model estimates indicated that the correlated paths between the latent factors of Impulsivity versus Constraint and Fear-Inhibition (r = .024, p = .738), PA and Dysphoria (r = .038, p = .611), and Dysphoria and Fear-Inhibition (r = −.048, p = .527) were nonsignificant. Hence, in the interest of parsimony, we removed these three paths. Based on the MIs, we made four theoretically or methodologically meaningful post hoc modifications (see Figure 2). First, we added a path from the latent PA/Interest factor to the observed global impulsivity indicator. The rationale for this modification was based on models from both the personality and temperament literatures, which associate extraversion with impulsivity. For example, in Eysenck and Eysenck’s (1975) original model of personality, the extraversion dimension included impulsivity. Although many impulsivity items were subsequently shifted to the psychoticism dimension (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985), Eysenck’s extraversion construct is still defined by several impulsivity-related features (i.e., sensation-seeking, venturesome). In addition, Depue and Collins (1999) have argued that impulsivity is one of the two central characteristics of extraversion. Further, in factor analytic studies of Rothbart’s model, the CBQ Impulsivity scale loads highly on the Extraversion/Surgency factor.

Figure 2.

Modified CFA model.

Second, we added a path from the latent Constraint versus Impulsivity factor to the observed global sociability indicator. The Constraint versus Impulsivity factor includes two core processes of self-regulation/constraint, an essential determinant of children’s social and emotional adjustment: voluntary and effortful control (e.g., inhibitory control) and involuntary or reactive control (low levels of which are expressed as impulsivity) (Eisenberg, Spinard, Fabes, Reiser, Cumberland, Valiente et al., 2004; Lengua, 2003). The sociability indicator emphasizes prosocial and appropriate interactions between the child and the experimenter. Thus, this path indicates that low inhibitory control/high impulsivity is negatively associated with sociability and pro-social behavior. The justification for this modification was based on an extensive literature suggesting that self-regulation is essential for the development and maintenance of social relationships, social competence, and pro-social behavior in children and adults. Specifically, numerous studies have found that inhibitory and effortful control predict high levels of social competence (e.g., Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 2004; Lengua, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006) and pro-social behavior (Eisenberg, Guthrie, Fabes, Reiser, Murphy, Holgren, et al., 1997; Kochanska et al., 1997). In contrast, impulsivity or reactive undercontrol has been consistently linked to lower social competence and pro-social behavior (Bush, Lengua, & Colder, 2010; Eisenberg et al., 2004; Lengua, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

Third, we correlated the residuals of the observed initiative and interest indicators. Initiative loaded on the Sociability factor as it was coded only when exhibited in the context of an interaction with the experimenter (i.e., taking the initiative in an activity with the experimenter). However, initiative can be conceptualized as a more specific manifestation of interest. In contrast, interest was a broader construct that could be demonstrated in a social or non-social context.

Lastly, we correlated the residuals of the observed PA and anticipatory PA indicators. Similar to the variables of interest and initiative, PA and anticipatory PA contain overlapping content, as anticipatory PA is an instance of PA exhibited before an expected reward or enjoyable activity.

The fit of the model incorporating these selected modifications is shown in Table 3. Model fit was acceptable, with CFI = .924, and RMSEA = .087 (90% CI = .074–.099).

Discussion

The structure of temperament traits in young children has been the subject of extensive debate, with different models proposing different dimensions (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Thomas & Chess, 1977; Rothbart, 1981). This research has relied almost exclusively on parent-report measures, which are economical and use parents’ observations across contexts and over time but are also vulnerable to perceptual and response biases (Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Stifter et al., 2008). We sought to extend this literature by using a laboratory observational measure to explore the structure of temperament in a preschool-age sample.

We used a two-stage factor analytic approach, with EFA conducted on one sample and CFA on a second sample. Based on the goodness-of-fit criteria used by Hopwood and Donellan (2010), we retrieved an adequately fitting model consisting of the higher-order traits of Sociability, PA/Interest, Dysphoria, Fear/Inhibition, and Constraint versus Impulsivity. Although several theoretically or methodologically meaningful post hoc modifications were needed to improve model fit, it is noteworthy that we were able to derive an adequately fitting model given the low success rate of prior CFA studies of temperament and personality (Church & Burke, 1994; Hopwood & Donnellan, 2010; Marsh et al., 2010; Mc-Crae et al., 1996). Our model, using an observational measure of temperament in preschoolers, overlaps with, but also diverges in meaningful ways from, previous models based largely on parent-reports. In what follows we discuss each of the factors identified in our model in the context of the extant literature (also see Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Common Temperament and Personality Dimensions

| Common dimensions | Thomas and Chess | Buss and Plomin | Rothbart and Colleagues | Mervielde and Asendorpf | Caspi and Shiner | Current findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | Extraversion | Sociability | Extraversion/Surgency | Extraversion | Extraversion | PA/Interest Sociability |

| Neuroticism | Neuroticism | Emotionality | Negative affectivity | Neuroticism | Neuroticism | Dysphoria Fear/Inhibition |

| Conscientiousness | Task Persistence | Effortful Control | Persistence | Conscientious | Constraint vs. Impulsivity | |

| Activity | Activity | Activity | Extraversion/Surgency | Activity | ||

| Agreeableness | Agreeable | Sociability | ||||

| Openness | Openness |

Note. Adapted from “How Are Traits Related to Problem Behavior in Preschoolers? Similarities and Contrasts Between Temperament and Personality,” S. S. W. De Pauw, I. Mervielde, & K. G. Van Leeuwen, 2009, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 309–325. Copyright 2005 by Springer.

Sociability and PA/Interest

Extraversion has consistently emerged as a higher-order factor in most temperament and personality models. However, theorists differ regarding the fundamental features that comprise the trait (Depue & Collins, 1999; Lucas, Diener, Grob, Suh, & Shao, 2000; Olino, Klein, Durbin, Hayden, & Buckley, 2005). Some investigators (e.g., Ashton, Lee, & Paunonen, 2002; Buss & Plomin, 1984; Costa & McCrae, 1980; Costa & McCrae, 1984) emphasize social or interpersonal features as the central characteristic of extraversion, whereas others (e.g., Depue & Collins, 1999; Gray, 1970) view the core of extraversion as reward-seeking/sensitivity (i.e., a motivational system that regulates the propensity to approach and engage in activities that are rewarding). Additionally, based on evidence suggesting that the associations of PA with the other facets of extraversion are stronger than the associations among the other facets, Watson and Clark (1997) have proposed that PA represents the “glue” that holds extraversion together (also see Lucas et al., 2000).

Our solution produced two factors that fall under the broad rubric of extraversion. Similar to Watson and Clark’s (1997) model of extraversion, our PA/Interest factor emphasizes PA as a core characteristic. Moreover, its facets of anticipatory PA and interest are also consistent with models of extraversion that emphasize appetitive and reward-seeking/sensitivity behavior (e.g., Depue & Collins, 1999; Gray, 1970; Lucas et al., 2000). Our PA/Interest factor was also associated with impulsivity, which has been considered an important aspect of extraversion in several models (e.g., Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985; Depue & Collins, 1999). Moreover, in two samples of young children, Kochanska and colleagues (2007) found that structured laboratory assessments of PA were positively associated parent ratings of child impulsivity.

We also identified a factor that we labeled “Sociability.” Analogous to Buss and Plomin’s (1984) and McCrae and Costa’s (1987) views of extraversion, our Sociability factor can be conceptualized as emphasizing surgent interpersonal traits (i.e., sociability, initiative, and dominance). The interpersonal aspect of extraversion has been divided into agency (i.e., initiative and dominance) and affiliation (i.e., sociability) (Depue & Collins, 1999). Hence, it is interesting that our Sociability factor includes aspects of each of these traits. Some of these traits are also included in the agreeableness factor in the five-factor model. For example, sociability and dominance are subsumed under agreeableness in the FFM (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 1987) and Caspi and Shiner’s (2006) developmental temperament/personality model.

The finding that PA/Interest and Sociability emerged as separate factors can be interpreted in several ways. First, the facets of extraversion might not coalesce into one higher-order factor until later in development. Second, the split in extraversion may be attributable to our laboratory observational measure. Most Lab-TAB tasks involved some degree of interaction between the child and experimenter, which may have allowed Sociability to emerge as a distinct factor. Third, our findings may accurately reflect the nature of extraversion, as several previous studies have found that PA and reward sensitivity are more closely related to each other than to sociability (Cunningham, 1988; Lucas et al., 2000; Olino et al., 2005). Finally, and somewhat related to the previous point, our PA/Interest and Sociability factors bear some resemblance to the FFM distinction between Extraversion and Agreeableness. Although Sociability and Agreeableness are partially distinct constructs (e.g., a child can seek social interaction yet be disagreeable (hostile and aggressive), affiliation and dominance have been included as facets of both dimensions (Caspi & Shiner, 2006). Hence, our findings can also be interpreted as indicating that Agreeableness is evident as a distinct dimension of temperament as early as the preschool period.

Dysphoria and Fear

In contrast to most traditional temperament models, the FFM, and the consensual models, in our model negative emotionality/neuroticism was split into two separate factors, Dysphoria and Fear/Inhibition. Whereas anger and sadness were highly associated (i.e., loading on the Dysphoria factor), fear was distinct from these other negative emotions (i.e., loading on the Fear/Inhibition factor). These findings are consistent with Lewis and Ramsey’s (2005) hypothesis that sadness and anger exhibit a strong relationship and continuity over time because both reflect an underlying emotional system that is responsive to the blockage of important goals. Similarly, Putnam, Ellis, and Rothbart (2005) have suggested that anger and sadness are highly correlated because both emotions are elicited by actual loss or suffering, whereas fear represents the anticipation of potential loss or punishment. Given the young age of the current sample, this suggests that fear may increase over time as the children’s ability to anticipate future events will grow as a function of cognitive development.

Our separate Dysphoria and Fear/Inhibition factors are consistent with findings from several recent studies of young children. In samples of infants and young children, Putnam and colleagues (2005) observed strong associations between parent reports of sadness and anger (correlations ranging from .50–.65) but lower correlations between each of these emotions and fear (.25–.40). Similarly, in a preschool sample, Durbin, Klein, Hayden, Buckley, & Moerk (2005) reported that laboratory observations of anger and sadness were significantly correlated (r = .31), but neither was significantly correlated with fear (rs = −.05 and .19, respectively). An important task for future developmental research is to determine at what age dysphoria and fear/inhibition are consolidated into a more adult/adolescent-like pattern of negative emotionality/neuroticism.

Constraint Versus Impulsivity

Our Constraint versus Impulsivity factor embodies aspects of both Rothbart’s Effortful Control and the FFM and Caspi and Shiner’s Conscientious factors. Specifically, our factor subsumes lower-order facets (i.e., inhibitory control, impulsivity) related to behavioral regulation or impulse control (i.e., the ability to inhibit a dominant response). Behavioral ratings of compliance also loaded on this factor, presumably reflecting the adherence to rules and respect for authority that are characteristic of high Conscientiousness (Caspi & Shiner, 2006). However, given the nature of our measures, we were not able to assess the self-regulatory processes of attention (i.e., shifting and focusing) contained in these models. In addition, our Constraint versus Impulsivity factor does not include the aspects of orderliness, dependability, and achievement motivation found in the FFM and Caspi and Shiner’s (2006) models, which may not be manifested until later in childhood (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Slotboom, Havill, Pavlopoulos, & De Fruyt, 1998). Additionally, we found that Constraint versus Impulsivity was associated with behavioral ratings of sociability, which is consistent with research suggesting that inhibitory control (the ability to plan and suppress one’s inappropriate behavior) is essential for prosocial and appropriate behavior (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2000; Lengua, 2003). In contrast, children high in impulsivity/reactive undercontrol (inability to delay or wait for a desired goal or object) are prone to engage in socially inappropriate and nonprosocial behavior (e.g., aggression) (Eisenberg et al., 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2000; Lengua, 2003). Finally, similar to Tellegen’s higher-order Constraint factor, which includes aspects of both agreeableness and conscientiousness, our Constraint versus Impulsivity factor includes elements (i.e., compliance) that may subsequently develop into Agreeableness (Tellegen, 1985).

Unlike some classic temperament models (Buss & Plomin, 1984; Thomas & Chess, 1977), Activity did not emerge as an independent factor. Consistent with other models, however, it loaded on our PA/Interest factor (Rothbart et al., 2001). However, it also had a high cross loading on the Constraint versus Impulsivity factor and therefore was removed from our model. These results are consistent with Martin, Wisenbaker, and Huttunen’s (1994) finding that activity level is a complex trait that loads on several factors. Likewise, Caspi and Shiner (2006) propose that activity level serves as a lower-order facet of extraversion in early childhood but may also be associated with the poorly regulated motor output and impulsive behavior associated with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD).

Finally, unlike the FFM and Caspi and Shiner’s (2006) consensual model, we did not find Agreeableness and Openness factors. However, as noted above, our Sociability factor overlaps with Agreeableness. Specifically, Agreeableness and Sociability are both characterized by affiliative, prosocial, and dominant behavior (Caspi & Shiner, 2006). Laboratory observations using interactions with peers rather than an experimenter might produce a clearer Agreeableness factor. Our failure to find an Openness factor is not surprising, as the Lab-TAB is not designed to assess this construct. Openness has received limited attention in the temperament literature and remains a controversial construct in the personality literature because of disagreement regarding its definition and content (McCrae & Costa, 1987; Digman, 1990; Goldberg, 1993). Several parent-report (e.g., CA Child Q-sort, Inventory of Childhood Individual Differences) and self-report (e.g., Berkley Puppet Interview) measures have been used to assess Openness in young children (Abe, 2005; Halverson et al., 2003; Measelle et al., 2005). However, it will be challenging to develop age-appropriate behavioral measures of Openness, which includes intellectual curiosity, imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, and attentiveness to inner feelings, and to ensure that they are distinct from general intelligence, language skills, and other traits such as approach, interest, sociability, and behavioral inhibition. However, such work is important to help determine whether Openness is a relevant trait in early childhood or represents a later emerging trait.

In sum, our laboratory measure yielded a trait structure in early childhood that overlaps with, but is somewhat distinct from, those that have been previously identified by parent-report. While some of these variations may be ascribed to differences in measurement, others may reflect age-specific patterns in the structure of temperament traits.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several factors constrain the interpretation of our findings. First, Lab-TAB episodes were designed to elicit particular emotions and behaviors. While this increases the chances of observing relevant responses, it raises the question of whether the child’s behavior is largely attributable to situation-specific, rather than trait, influences. To maximize cross-situational variance, we averaged most variables across all 12 episodes before including them in the analyses. In addition to reducing the influence of episode-specific factors, this approach allows incorporation of behaviors that are atypical in particular contexts (e.g., fearfulness in an episode designed to elicit exuberance; interest in an episode designed to elicit frustration); these atypical behaviors may be particularly informative with respect to temperament.

Second, the sample of child behavior and emotions provided by the Lab-TAB is based on a limited number of contexts. One particularly important domain that is not assessed in the Lab-TAB is behavioral and emotional reactions in interactions with peers. Peer interactions may provide better measures of certain traits like agreeableness than adult/experimenter-child interactions can. More specifically, because child-peer interactions are more symmetrical with respect to power and control, they may be better suited to elicit such facets of agreeableness as warmth, empathy, aggression, and dominance. As such, future studies using observational measures should consider incorporating tasks that involve child-peer interactions.

Third, although a major aim of the current study was to use a measure other than parent-reports, future studies should build on this by using multimethod assessments to increase the generalizability of the findings to settings outside of the laboratory and tease apart which differences are attributable to developmental factors and which are attributable to measurement factors. Similarly, future studies should also examine different types of observational measures (i.e., scripted laboratory procedures vs. naturalistic interactions) because even among observational measures, different kinds of assessments have yielded different patterns of associations within the same sample (Kochanska et al., 2007). However, one of the challenges in doing multimethod studies will be to ensure that the different methods are assessing a similar set of constructs. Otherwise, it will be difficult to disentangle variation attributable to methods from variation in the contents and coverage of the measures.

Fourth, because this study was cross-sectional, it remains unclear as to how development may influence the overall structure of temperament. Future studies should examine the long-term stability of the structure of child temperament and explore how it changes and/or becomes more or less differentiated with age.

Fifth, the current study did not examine gender differences in the structure of temperament traits. Future studies should test gender invariance using an observational measure to determine whether the structure of child temperament differs as a function of gender.

Lastly, the participants in this sample were predominantly middle class and White/European American. Although these sociodemographic characteristics may limit the generalizability of our findings, they are representative of the population in our geographic region. Future studies should examine the structure of temperament in preschool-aged children using more ethnically diverse samples.

In conclusion, this study used an alternative approach to parent-report measures, a laboratory observational measure, to examine the structure of temperament in preschool-age children. Using a two-stage EFA/CFA approach, we identified a five-factor structure that shares a number of similarities with those derived from parent-report measures but also demonstrates some notable differences. Although some of these variations may be attributed to differences in measurement, our model suggests that it is also important to consider the possibility of age-specific differences in the structure of temperament.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants: National Institute of Mental Health RO1 MH069942 (to D.N.K.) and a General Clinical Research Centers Grant M01-RR10710 to Stony Brook University from the National Center for Research Resources.

Contributor Information

Margaret W. Dyson, Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University

Thomas M. Olino, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

C. Emily Durbin, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University.

H. Hill Goldsmith, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Daniel N. Klein, Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University

References

- Abe JAA. The predictive validity of the Five-Factor Model of personality with preschool age children: A nine year follow-up study. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Abe JAA, Izard CE. A longitudinal study of emotion expression and personality relation in early development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:566–577. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TW, Rubin H. Statistical inference in factor analysis. Proceedings of Third Berkley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. 1956;5:111–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton MC, Lee K, Paunonen SV. What is the central feature of extraversion? Social attention versus reward sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;86:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli C, Caprara GV, Rabasca A, Pastorelli C. A questionnaire for measuring the big five in late childhood. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:645–664. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush NR, Lengua L, Colder C. Temperament as a moderator of the relation between neighborhood and children’s adjustment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. New York, NY: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Block JH, Block J. Preschool activity level: Personality correlates and developmental implications. Child Development. 1980;51:401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Rothbart MK. Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1992;12:154–173. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson S. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Shiner RL. Personality development. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 300–364. [Google Scholar]

- Church AT, Burke PJ., Jr Exploratory and confirmatory tests of the big five and Tellegen’s three- and four-dimensional models. Personality Processes and Individual Differences. 1994;66:93–114. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL. Factor-analytic methods of scale development in personality and clinical psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:754–761. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:668–678. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Personality as a life-long determinant of wellbeing. In: Malatesa CZ, Izard CE, editors. Emotion in adult development. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MR. What do you do when you’re happy or blue? Mood, expectancies, and behavioral interest. Motivations and Emotion. 1988;12:309–331. [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, Mervielde I, Hoekstra HA, Rolland JP. Assessing adolescents’ personality with the NEO PI-R. Psychological Assessment. 2000;7:329–345. doi: 10.1177/107319110000700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SSW, Mervielde I. Temperament, personality and developmental psychopathology: A review based on the conceptual dimensions underlying childhood traits. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;41:313–329. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SSW, Mervielde I, Van Leeuwen KG. How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:309–325. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman SJ. Functional and dysfunctional impulsivity: Personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:95–102. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM, Inouye J. Further specification of the five robust factors of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM, Shymelov AG. The structure of temperament and personality in Russian children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:341–351. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Klein DK, Olino TM. Stability of laboratory-assessed temperamental emotionality traits from ages 3 to 7. Emotion. 2007;7:188–199. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin CE, Klein DN, Hayden EP, Buckley ME, Moerk KC. Temperamental emotionality in preschoolers and parental mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal. 2005;114:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Murphy RH, Holgren R, Losoya S. The relations of regulation and emotionality to resiliency and competent social functioning in elementary school children. Child Development. 1997;68:295–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinard TL, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Cumberland SA, Valiente C, Thompson M. The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development. 2004;75:25–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Development of a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:868–888. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Inventory. San Diego, CA: EdITS; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Personality and individual differences. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Wildman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JR, Van Hulle CA, Aksan N, Essex MJ, Goldsmith HH. Deriving childhood temperament measures from emotion-eliciting behavioral episodes: Scale construction and initial validation. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23:337–353. doi: 10.1037/a0021746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologists. 1993;48:26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. Analyses of Digman’s child personality data: Derivation of big-five factor scores from each of six samples. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:709–743. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.695161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Campos JJ. The structure of infant temperamental dispositions to experience fear and pleasure: A psychometric perspective. Child Development. 1990;61:1944–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. Unpublished manuscript. 1995. Laboratory temperament assessment battery: Preschool version. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RL. Factor analysis. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1970;8:249–266. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(70)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano WG, Ward D. Probing the Big Five in adolescence: Personality and adjustment during a developmental transition. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:425–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halverson CF, Havil VL, Deal J, Baker SR, Victor JB, Pavopoulos V, Wen L. Personality structure as derived from parental ratings of free descriptions of children: The inventory of child individual differences. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:995–1026. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Unpublished manuscript. 1975. Four factor index of social status. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Donnellan MB. How should the internal structure of personality inventories be evaluated? Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:332–346. doi: 10.1177/1088868310361240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Caspi A, Robins RW, Moffit TE, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The little 5—Exploring the nomological network of the 5-Factor Model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Development. 1994;65:160–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Temperament in human nature. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1994. Galen’s prophecy. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. Biology and the child. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional and personality development. 5. New York, NY: Wiley; 1998. pp. 177–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, Garcia-Coll C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development. 1984;55:2212–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Temperamental inhibition in early childhood. In: Plomin R, Dunn J, editors. The study of temperament: Changes, continuities and challenges. Hills-dale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Penney SJ, Doobay AF. Early positive emotionality as a heterogeneous trait: Implications for children’s self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:1054–1066. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Coy KC. Inhibitory control as a contributor to conscience in childhood: From toddler to early school age. Child Development. 1997;68:263–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Jacques TY, Koenig AL, Vandegeest KA. Inhibitory control in young children and its role in emerging internalization. Child Development. 1996;67:490–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnstamm GA, Halverson CF, Mervielde I, Havil V, editors. Parental descriptions of child personality: Developmental antecedents of the big five. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Chung SS, Wessels H, Broberg AG, Hwang CP. Emergence and construct validation of the big five factors in early childhood: A longitudinal analysis of their ontogeny in Sweden. Child Development. 2002;73:1517–1524. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ. Associations among emotionality, self-regulation, adjustment problems, and positive adjustment in middle childhood. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:595–618. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramsey D. Infant emotional and cortisol responses to goal blockage. Child Development. 2005;76:518–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RE, Diener E, Gobb A, Suh EM, Shao L. Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:452–468. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdandzic M, van den Boom DC. Multimethod longitudinal assessment of temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:121–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey PM, Markey CN, Tinsley BJ, Ericksen AJ. A preliminary validation of preadolescents’ self-report using the five-factor or personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999). findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Lüdtke O, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJ, Trautwein U, Nagengast B. A new look at the Big Five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:471–491. doi: 10.1037/a0019227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Trautwein U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluation of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:439–476. [Google Scholar]

- Martin RP. The temperament assessment battery for children. Brandon, VT: Clinical Psychology Publishing; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Martin RP, Wisenbaker J, Huttunen M. Review of factor analytic studies of temperament measure based on the Thomas-Chess structural model: Implications for Big Five. In: Halverson CF, Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy adulthood. Hillside, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 157–172. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:81–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Zonderman AB, Costa PT, Bond M, Paunonen SV. Evaluating replicability of factors in the revised NEO personality inventory: Confirmatory factor analysis versus procustes rotation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:352–566. [Google Scholar]

- Measelle JR, John OP, Ablow JC, Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Can children provide coherent, stable, and valid self-reports on the Big Five dimensions? A longitudinal study from ages 5 to 7. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:90–106. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervielde I, Asendorpf JB. Variable-centered versus person-centered approaches to childhood personality. In: Hampson SE, editor. Advances in personality psychology. Taylor & Francis; Philadelphia: 2000. pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mervielde I, Buyst V, De Fruyt F. The validity of the big-five as a model for teachers’ ratings of individual differences among children aged 4–12. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;19:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Mervielde I, De Fruyt F. Construction of the Hierarchical Personality Inventory for Children (HiPIC) In: Mervielde I, Deary IL, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality psychology in Europe: Proceedings of the eighth European conference on personality psychology. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press; 1999. pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Durbin EC, Hayden EP, Buckley ME. The structure of extraversion in preschool aged children. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Presley R, Martin RP. Toward a structure of preschool temperament: Factor structure of temperament assessment battery for children. Journal of Personality. 1994;62:415–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M. Childhood temperament. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33:249–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In: Eliaz A, Angleitner A, editors. Advances in research in temperament. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development. 2006;29:386–401. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Measurement of temperament in infancy. Child Development. 1981;52:569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA. Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:55–66. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament in children’s development. In: Damon W, Lerner R, Eisenberg, editors. Handbook of child psychology. 6. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 1–99. Social, emotional, and personality development. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Derryberry D, Hershey K. Stability of temperament in childhood: Laboratory infant assessment to parent report at seven years. In: Molfese VJ, Molfese DL, editors. Temperament and personality development across the life span. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Goldsmith HH. Three approaches to the study of infant temperament. Developmental Review. 1985;5:237–260. [Google Scholar]