Abstract

Low birth weight is an important risk factor for impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes later in life. One hypothesis is that fetal β-cells inherit a persistent defect as a developmental response to fetal malnutrition, a primary cause of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Our understanding of fetal programming events in the human endocrine pancreas is limited, but several animal models of IUGR extend our knowledge of developmental programming in β-cells. Pathological outcomes such as β-cell dysfunction, impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes are often observed in adult offspring from these animal models, similar to the associations of low birth weight and metabolic diseases in humans. However, the identified mechanisms underlying β-cell dysfunction across models and species are varied, likely resulting from the different methodologies used to induce experimental IUGR, as well as intraspecies differences in pancreas development. In this review, we first present the evidence for human β-cell dysfunction being associated with low birth weight or IUGR. We then evaluate relevant animal models of IUGR, focusing on the strengths of each, in order to define critical periods and types of nutrient deficiencies that can lead to impaired β-cell function. These findings frame our current knowledge of β-cell developmental programming and highlight future research directions to clarify the mechanisms of β-cell dysfunction for human IUGR.

Keywords: Insulin Secretion, Pancreas, Pregnancy, Diabetes, Fetus

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is growing worldwide. It is now well established that interactions between an individual’s genetic makeup and environment contribute to the development of T2DM (Gerich 1998). Evidence continues to mount showing that T2DM is more prevalent among subjects that were intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) during fetal development, indicating that the defects in glucose homeostasis originate in utero (Barker et al. 1993; Newsome et al. 2003; Ravelli et al. 1998). The reciprocal relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity (Table 1) suggests that defects occur in either insulin secretion capacity or insulin action at target tissues, or both in the case of T2DM (Kahn et al. 1993; Robertson 1992; Weir 1993a, 1993b). Despite differences in the type, timing, and duration of intrauterine insult, most animal models of IUGR have similar outcomes of impaired glucose tolerance or T2DM. However, because the etiology of these phenotypes can involve a variety of mechanisms, they are relatively nonspecific endpoints. Therefore, care is required when interpreting animal studies and planning interventions to ameliorate β-cell dysfunction. In this review, we discuss the evidence for β-cell dysfunction in human IUGR and identify several potential mechanisms found in animal models that begin to explain these outcomes.

Table 1.

Measurements of glucose metabolism and insulin secretion.

| Term | Definition | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Insulin secretion |

|

|

| Insulin sensitivity |

|

|

| Insulin resistance |

|

|

| Insulin disposition |

|

|

| Impaired Glucose Tolerance |

|

|

β-CELL DEFECTS IN SMALL FOR GESTATIONAL AGE INFANTS

Human studies generally compare outcomes in small for gestational age neonates (SGA; usually defined as <10th percentile for birth weight, although the statistical cut-off can vary) to appropriate for gestational age neonates (AGA). Although birth weight is the most accessible proxy for fetal growth restriction, the statistical nature of this classification may introduce heterogeneity into human studies, whereas the term IUGR describes a pathophysiological process. In most cases, IUGR occurs in genetically normal fetuses that are restrained from reaching their full growth potential. This is usually associated with placental insufficiency and almost always with fetal under-nutrition, which causes asymmetric fetal growth (Platz and Newman 2008). IUGR is rarely diagnosed before 22–24 weeks of gestation, but detection is improving with increasing use of ultrasonography (Creasy et al. 2004; Ferrazzi et al. 2002). Despite the limitations of the SGA classification, the human studies discussed below provide substantial evidence for relationships between birth weight and metabolic syndromes resulting from β-cell dysfunction.

Based on umbilical cord blood sampling, SGA fetuses have lower blood oxygen levels; decreased plasma amino acids, glucose, and insulin (Economides et al. 1989; Setia et al. 2006); and increased catecholamine concentrations (Greenough et al. 1990) relative to AGA controls. Glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS; Table 1) has been measured in IUGR fetuses (diagnosed by ultrasound) prior to the onset of labor or maternal anesthesia. They demonstrated an almost complete absence of first-phase insulin secretion compared to a robust response in control fetuses (Table 2) (Nicolini et al. 1990). Elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for impaired GSIS in IUGR fetuses has been limited to measurements of pancreatic morphology. One study found no differences in the β-cell population between SGA (<10th percentile) and AGA fetuses (50th-75th percentile) at 36 weeks of gestation (Beringue et al. 2002). However, newborns with severe SGA (<3rd percentile) had a lower fraction of β-cells and smaller islets with less pronounced vasculature than AGA newborns (~40th percentile) at ~34 weeks of gestation (Van Assche et al. 1977). Together, these studies demonstrate that, at least in severe IUGR fetuses, the pancreatic β-cell population and insulin secretion are reduced (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fetal and pancreatic characteristics in humans and animal models of IUGR.

| Rodent models of IUGR | Ovine models of IUGR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Human SGA/IUGR subjects | Uterine artery ligation | Caloric restriction | Low protein diet | Hyperthermic placental insufficiency | Carunclectomy placental restriction | Hypoglycemic | |

| Fetal Characteristics | |||||||

| Timing of insulta | Variable, but >0.55 G | 0.82 to 0.91 G | 0.68 to 1 G | 0 G to 1 G | >0.47 to 1 G | >0.76 to 1 G | 0.8 to 0.93 G |

| Hypoxemia | Yes | Yes, 0.82–0.86 G; Normal at birth | None | None | ↓ 34%–59% | ↓ 23%–35% | None |

| Hypoglycemia | Yes | Yes, 0.82–0.86 G; Normal at birth | NR | NR | ↓ 31%–52% | ↓ 15–41% | ↓ 46 – 54% |

| Hypoinsulinemia | Yes | Yes, 0.82–0.91 G; Normal at birth | ↔ | ↔ | ↓ 69% | ↔ | ↓ 26–36% |

| Fetus weight | ↓ ≥ 2SD | ↓ 15–20% | ↓ 15–20% | ↓ 5–8% | ↓ 24–57% | ↓ 21 – 29% | ↓ 17–24% |

| Other factors Defined | ↑ catecholamines | NR | ↑ corticosterone ↓ IGF-II ↓ VEGF |

↔corticosterone ↓ taurine |

↔corticosterone ↑ taurine ↑ catecholamines |

↔corticosterone | ↑ corticosterone ↑ taurine ↔catecholamines |

|

| |||||||

| Fetal Pancreatic Characteristics | |||||||

| β-cell mass | NR | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ 76% | ↔ | ↔ |

| β-cell fraction | ↓/↔ | NR | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ 42% | ↔ | ↔ |

| Islet vascularization | ↓ | ↓ | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ 33%b | NR | NR |

| β-cell proliferation | NR | ↓ | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ 72% | NR | NR |

| β-cell neogenesis | NR | NR | ↓ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | NR |

| β-cell apoptosis | NR | ↔ | ↔ | ↑ | ↔ | NR | NR |

| In vitro β-cell responsiveness | NR | ↓ at P7 | NR | ↓ (amino acids) | ↓ 82% | NR | ↓ |

| In vivo β-cell responsiveness | ↓ 89% | NR | NR | NR | ↓ 76% | ↓ | ↓ 45% |

Abbreviations used: NR: Not reported in the literature to the authors’ knowledge;↔: Factor was measured, but no change was found; G: fraction of gestation; P: postnatal days.

The timing of the insult for humans and sheep with placental insufficiency is based on initial diagnoses for IUGR or lower index of placental function.

Rozance and Limesand, unpublished data.

In the literature, there are conflicting reports describing neonatal insulin secretion in SGA subjects, spanning from β-cell dysfunction to overcompensation. One report has shown that β-cell dysfunction persists in SGA infants at 48 hours, but they also tend to be more sensitive to insulin, which may mask impaired glucose tolerance (Bazaes et al. 2003). The relationship between insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity is hyperbolic in nature. Thus, for a given degree of glucose tolerance, the product of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity is constant and changes are reciprocal (i.e., insulin secretion decreases in response to greater insulin sensitivity) (Kahn et al. 1993). Therefore, it is important to account for insulin sensitivity when measuring insulin secretion. Another report found that by 72 hours, SGA infants had greater plasma insulin concentrations compared to AGA infants, but glucose was not different (Wang et al. 2007). In this study, SGA subjects were not as growth restricted as those examined in the 48 hour study, making direct comparisons difficult, but also suggesting a trend for degrees of IUGR. Several case series identify SGA newborns presenting with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Although retrospective and selective, these cases support β-cell overcompensation in some SGA newborns (Collins and Leonard 1984; Collins et al. 1990; Hoe et al. 2006). More thorough evaluation is required to determine which infants have persistent β-cell dysfunction and which develop hyper-responsive β-cells, as well as the underlying mechanisms responsible for these differences.

Many SGA children exhibit catch-up growth and reach normal height and weight by three years of age (Bazaes et al. 2004; Colle et al. 1976; Iniguez et al. 2006). Those showing catch-up growth, especially for length, have greater insulin secretion compared to those without catch-up growth (Bazaes et al. 2004; Colle et al. 1976; Crowther et al. 2000; Hofman et al. 1997; Soto et al. 2003). Catch-up growth is also associated with increased adiposity, raising the incidence of insulin resistance by the time children reach 5 years of age (Hofman et al. 1997; Ong et al. 2000). This places a greater burden on a β-cell population already compromised by fetal malnutrition, perhaps accelerating the progression towards β-cell failure (Mericq et al. 2005).

In SGA children and young adults, reports of insulin secretion and β-cell function are discordant. Interpretation of results is complicated by the development of insulin resistance (Bazaes et al. 2004; Hofman et al. 1997; Mericq et al. 2005; Soto et al. 2003), in addition to subject population heterogeneity and confounding environmental variables (e.g., diet, exercise). Even with these limitations, studies that have measured insulin secretion and accounted for insulin sensitivity have shown that insulin secretion is impaired in SGA subjects as children (up to 14 years of age) (Li et al. 2001) and in otherwise healthy, glucose tolerant, 19-year-old men without a family history of diabetes (Jensen et al. 2002). These studies contrast to several reports indicating that β-cell function was unaffected (Crowther et al. 2000; Flanagan et al. 2000; Soto et al. 2003; Veening et al. 2003). However, these negative studies did not measure insulin sensitivity. Therefore, β-cell dysfunction relative to insulin resistance is apparent, and over time, these factors combine to cause T2DM in adults born SGA.

CRITICAL WINDOWS FOR FETAL ISLET DEVELOPMENT

Before comparing and contrasting islet deficiencies in animal models of IUGR, we must first consider the timing of events of pancreas morphogenesis and differentiation of endocrine cells. Pancreas development could be impacted differently depending on the timing and duration of restricted nutrition relative to the stage of development. For example, when rat dams are calorie-restricted during gestation and lactation, pup β-cell mass and function are reduced, but this reduction is less severe if the dam is fed adequate calories during lactation. Such postnatal interventions may impact outcomes more markedly in altricial species such as the rat, which undergo extensive islet maturation after birth, compared to precocial species, like the human and sheep. Moreover, in rodents, pancreas development appears to happen in discrete transitions, which allows us to dissect out stage-specific complications and relate them to the multifocal developmental progression found in the human and sheep pancreas (Table 3) (Cole et al. 2009; Sarkar et al. 2008).

Table 3.

Species comparison of critical periods for pancreas development.

| Mouse | Rat | Sheep | Human | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary transition | E9.5 (0.5G) | E11 (0.5G) | <24 dGA (<0.16G) | 25–26 dGA (0.09G) |

| Secondary transition | E13.5–E15.5 (0.71–0.82G) | E15–18 (0.68–0.82G) | 24–147 dGA (0.16–1.0G) | 7.5–40 wGA (0.19–1.0G) |

| Isletogenesis | E15–19 (0.79–1.0G) | E17–21 (0.77–0.95G) | 33–147 dGA (0.22–1.0G) | 1–40 wGA (0.28–1.0G) |

| Endocrine cell proliferation | E18.5–P30 (0.97–1.0G) | E21.5–22 (0.97–1.0G) | 33–147 dGA (0.22–1.0G) | 8–40 wGA (0.20–1.0G) |

| Term gestation | E19 | 22 | 147 dGA | 40 wGA |

Abbreviations used: Embryonic day (E); days gestational age (dGA); weeks gestational age (wGA); and fraction of gestation (G).

Organogenesis of the pancreas is a highly coordinated process with structural and cytological aspects. Early morphological events of pancreas formation appear to be phylogenetically conserved among mammals (Pictet et al. 1972a). The developmental process begins when the endoderm is specified to “the pancreatic state,” and after the primary transition, these protodifferentiated cells expand to form the pancreatic anlagen (Pictet et al. 1972a). The pancreas originates from the dorsal and ventral region of the foregut endoderm at embryonic day (E) 9.5 in the mouse, E11 in the rat, and 25–26 days gestational age (dGA) in the human (Pictet et al. 1972a; Pictet et al. 1972b; Piper et al. 2004; Wessells and Cohen 1967). Pancreatic precursor cells expand, forming a dense outgrowth that begins to lobulate and then elongate into branches (Cole et al. 2009; Jensen 2004; Piper et al. 2004; Rutter 1980). In rodents, the elongation is associated with a condensed mesodermal covering (Wessells and Cohen 1967). In contrast, human and sheep pancreatic buds appear to elongate into a loose mesenchymal bed, which occurs between 26 and 41 dGA in the human (Piper et al. 2004) and between 24 and 29 dGA in the sheep (Cole et al. 2009). Reasons for these morphological differences are undefined, but we expect that the mesenchymal cells provide factors to support pancreas development in all mammals (Bhushan et al. 2001; Norgaard et al. 2003; Wessells and Cohen 1967). Finally, the progenitor cell expansion culminates with the secondary transition (“differentiated state”) when mature secretory products are identified, occurring between E13.5–15.5 in the mouse and E15–18 in the rat (Pictet et al. 1972b; Wessells and Cohen 1967). The secondary transition begins before 24 dGA in sheep and at 52 dGA in humans and proceeds in conjunction with progenitor cell expansion, but defined end points are not evident during gestation in either species (Cole et al. 2009; Cole et al. 2007; Piper et al. 2004; Polak et al. 2000).

Studies using genetically engineered mice have defined a hierarchy of transcription factors that coordinates pancreas organogenesis and endocrine cell specification from pluripotent progenitors (for a comprehensive review see (Jensen 2004)). For brevity, we will only focus on transcription factors that have also been examined in humans and sheep. A homeodomain protein, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox-1 (Pdx-1), initiates differentiation and morphogenesis of the pancreatic epithelial progenitor cells and later becomes restricted to mature β-cells, where it is involved in transactivation of β-cell-specific genes (Offield et al. 1996; Sander and German 1997). In humans and sheep, a similar pattern of cellular expression of Pdx-1 is apparent (Cole et al. 2009; Piper et al. 2004). At the secondary transition in mice, neurogenin3 (Ngn3) is essential for committing pancreatic epithelial progenitor cells to an endocrine cell lineage (Gradwohl et al. 2000; Jensen et al. 2000). In humans, however, evidence for an absolute requirement of Ngn3 is unclear (del Bosque-Plata et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2006). Despite this, the temporal and spatial expression of Ngn3 indicates that it is involved in endocrine cell specification in humans and sheep (Cole et al. 2009; Sarkar et al. 2008; Sugiyama et al. 2007).

Two other processes that occur during pancreagenesis include the onset of mature islet cell replication and isletogenesis, both of which also exhibit temporal differences among species. In rodents, the newly formed endocrine cells are mitotically quiescent until near term (E19 mouse and E21.5 rats) (Jensen et al. 2000; Pictet et al. 1972b; Sander et al. 2000), whereas human β-cells begin to proliferate at 8 wGA, albeit at low levels, and continue replicating throughout gestation (Bocian-Sobkowska et al. 1999; Bouwens et al. 1997; Kassem et al. 2000; Polak et al. 2000). A similar time frame of onset and duration is found in sheep (Cole et al. 2007; Limesand et al. 2005). The formation of islet-like structures also happens earlier in humans and sheep than rodents. In humans and sheep, aggregates begin forming shortly after the onset of differentiation, resulting in primitive islets by week 11 in humans (Bocian-Sobkowska et al. 1999; Nieto 2002; Piper et al. 2004) and 33 dGA in sheep (Cole et al. 2009). In contrast, islets do not form until 0.78 of gestation in rodents (Jensen et al. 2000; Slack 1995). During isletogenesis, vascularization of the islets is also observed (Pictet et al. 1972b) and recent findings indicate that endothelial cells augment β-cell proliferation (Lammert et al. 2001; Nikolova et al. 2006).

In the human fetus, β-cells exhibit robust insulin secretion in response to insulin secretagogues (Adam et al. 1969; Nicolini et al. 1990). In rats, β-cells begin to be responsive near term, but the response is not robust until a week after birth (Kervran and Randon 1980; Kervran et al. 1979). In the sheep fetus, β-cells respond to glucose and arginine as early as mid-gestation, and the response improves toward term (Aldoretta et al. 1998; Molina et al. 1993). Strikingly, newborn lambs have a GSIS response that is almost 5 times that of the late-term fetus (Philipps et al. 1978). This enhanced GSIS occurs within 6 hours of parturition, suggesting that the changes are induced by the postnatal internal milieu, not a sudden β-cell expansion; GSIS potentiation has not been confirmed in human infants.

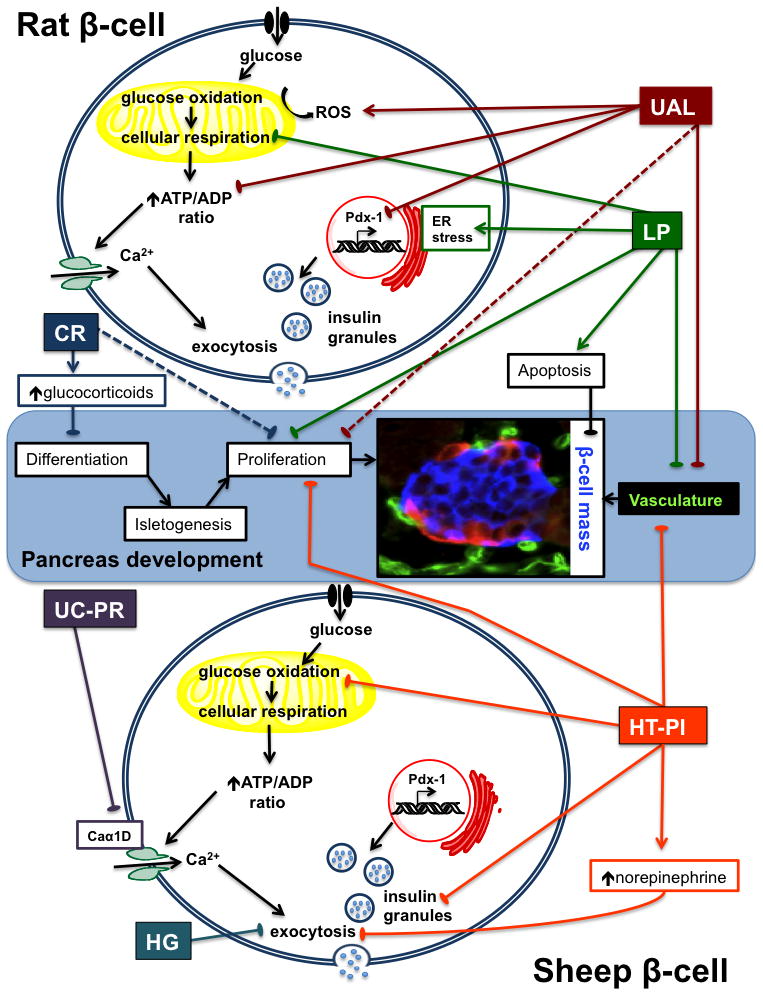

Morphological and cytological processes for pancreas development appear to be conserved among humans and species commonly used as models for IUGR. However, the timing and progression of pancreas development is different in precocious species compared to rodents (Table 3). The distinct developmental transitions observed in rats later in gestation provide insight into how pancreas development is affected by IUGR, while the sheep provides a model system more reminiscent of human pancreas development (Table 3). Regardless of species, critical windows of islet development include differentiation, proliferation, development of vasculature, and functional maturation of metabolism (Figure 1); all of these are potentially affected by fetal nutrient restriction.

Figure 1. Mechanisms for β-cell dysfunction in models of IUGR.

A schematic representation of pancreas development and processes controlling β-cell function is depicted. Identified β-cell impairments are shown for each of the rat and sheep models of IUGR. Rat IUGR models include uterine artery ligation (UAL), low protein diet (LP) and caloric restriction (CR). Sheep IUGR models include uterine carunclectomy-placental restriction (UC-PR), chronic hypoglycemia (HG), and hyperthermia-induced-placental insufficiency (HT-PI). A fetal sheep islet at 103 dGA is shown in the micrograph; it is immunostained for insulin (β-cell, blue), other endocrine cells (glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide cells, red), and vasculature (Griffonia simplicifolia 1, green). Solid lines indicate processes sensitive to nutrient restriction in the fetus; dashed lines indicate postnatal effects. Lines ending with arrows represent enhancement and lines ending with bars represent inhibition of the defined processes. Additional abbreviations used: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Caα1D, voltage-gated calcium channel α1D.

β-CELL DEFICIENCIES IN ANIMAL MODELS OF IUGR

In addition to obvious ethical issues, studies in humans are difficult because of our long life span, during which time complex environmental and genetic factors may cloud associations between fetal growth and adulthood diseases. Therefore, animal models of IUGR play a critical role in building our understanding of developmental programming of β-cells. Although no model perfectly replicates human circumstances, all of the rodent and sheep models discussed here show a clear association between fetal growth restriction and β-cell dysfunction (Table 2). However, the mechanisms for these adverse outcomes differ (Figure 1), which may reflect the type, timing, and duration of fetal insults.

Rodent models of IUGR

Uterine artery ligation model

Abrupt global nutrient and oxygen restriction is created by uterine artery ligation (UAL) in rats at E18–E19 (term is 22 days), causing IUGR (Table 2) (Ogata et al. 1986; Simmons et al. 1992; Wigglesworth 1964). The period of fetal insult is relatively brief, with reductions in fetal pH and oxygen lasting for 1–2 days and plasma glucose and insulin being reduced for 2–3 days prior to normalizing by birth (Ogata et al. 1986; Peterside et al. 2003). Simmons and colleagues have shown that UAL rat pups exhibit catch up growth and surpass controls, becoming obese by 26 weeks (Simmons et al. 2001). No irregularities in pancreas β-cell morphology are observed before 7 weeks of age, but by 15 weeks, β-cell mass is 50% of controls and continues to decline thereafter (Simmons et al. 2001). β-cell proliferation is lower at postnatal day (P) 14, which is associated with reductions in islet vascular density or other underlying β-cell defects that take several weeks to manifest (Ham et al. 2009; Stoffers et al. 2003). Interestingly, when UAL is conducted on rats at E17, just one day earlier than in the studies by Simmons, β-cell mass is reduced at P1 (De Prins and Van Assche 1982). Thus, earlier timing of UAL targets a different stage of pancreas development, causing reductions in β-cell mass and differentiation rather than impairments in maturation.

Fasting glucose and insulin concentrations are normal in UAL rats at P7, but they develop mild fasting hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia by 7 weeks and frank diabetes by 26 weeks of age. Insulin secretion stimulated with either glucose or leucine is impaired in newborns and progressively worsens with age, but responsiveness to arginine remains intact (Simmons et al. 2005; Simmons et al. 2001). These findings indicate that the β-cell defect is in metabolic coupling rather than a deficiency in the releasable pool of insulin (Simmons et al. 2001).

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are potential underlying mechanisms for β-cell dysfunction in UAL rats (Simmons et al. 2005). ATP production in response to glucose is lower in UAL islets compared to controls, which is partially explained by deficiencies in the mitochondrial electron transport chain and greater mitochondrial DNA point mutations (Simmons et al. 2005). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is also chronically elevated in UAL islets (Simmons et al. 2005), probably potentiated by hyperglycemia (Robertson and Harmon 2006). These factors likely create a self-supporting cycle in which abrupt fetal hypoxemia impairs mitochondrial function, which lowers the activity of the electron transport chain and augments ROS production, leading to further damage (Li et al. 2004).

Pdx-1 mRNA expression is lower in UAL fetuses (50%) and adults (80%) and has been shown to be downregulated by modification that silences heterochromatin (Park et al. 2008). In addition to transactivation of β-cell specific genes, Pdx-1 also regulates mitochondrial function in mature β-cells (Gauthier et al. 2004). In UAL fetuses, histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and Sin3A are recruited to the proximal promoter region, deacetylating core histones H3 and H4 and repressing Pdx-1. Demethylation of lysine 4 and methylation of lysine 9 on histone H3 also occur, reflecting alternative modifications to the core histones that result in the loss of USF-1 binding to Pdx-1 promoter. Finally, DNA methylation of the Pdx-1 gene further suppresses its expression in adult UAL rats (Park et al. 2008). These data provide evidence linking several of the cellular impairments associated with mitochondrial dysfunction to epigenetic modifications.

Neonatal treatment (P0–P6) with Exendin-4, a long-acting GLP-1 analog, prevents the loss of β-cell mass and normalizes β-cell proliferation in UAL pups (Stoffers et al. 2003). Exendin-4 treatment normalizes islet vascularity and VEGF protein expression (Ham et al. 2009), which may explain the improvements in proliferation. Fasting glycemia and glucose tolerance are also restored, and the development of diabetes is averted (Stoffers et al. 2003). Pdx-1 expression is maintained with Exendin-4 treatment (Stoffers et al. 2003), further confirming Pdx-1 as a major point for β-cell programming in the UAL model.

Caloric restriction model

Maternal caloric restriction (CR; 50% of control energy intake in most studies) of rat dams during the last week of gestation causes a 12–20% reduction in birth weight in about half of fetuses, which are selected as IUGR (Table 2) (Garofano et al. 1997, 1998b). One day-old CR-IUGR pups have reduced pancreas weight, insulin content, islet density, and β-cell mass, but islet size is similar to controls (Dumortier et al. 2007; Garofano et al. 1997, 1998a). β-Cell proliferation and apoptosis and islet vascularity are not different at E21 or P1. However, CR islets (E15) have fewer Ngn3 and Pdx-1 positive cells, indicating that β-cell differentiation is impaired (Dumortier et al. 2007; Garofano et al. 1997, 1998a). However, when CR is extended through lactation, additional declines in β-cell mass, number, and insulin content are observed in adulthood, indicating that β-cells are also susceptible to nutrient restriction after differentiation is complete (Garofano et al. 1998a, b, 1999).

Both aging and pregnancy are normal physiological stresses, and β-cells of CR rats appear to be poorly equipped to tolerate these events. During pregnancy, the endocrine pancreas of the mother normally expands by replication to overcome insulin resistance (Avril et al. 2002; Blondeau et al. 1999). However, 8-month-old CR rats, malnourished through weaning and fed an adequate diet thereafter, display an inability to expand their β-cell population and are hypoinsulinemic at mid-pregnancy (Avril et al. 2002; Blondeau et al. 1999). Interestingly, 4-month-old CR rats display normal adaptations to pregnancy, implicating an interaction between age and pregnancy in the plasticity of the adult CR pancreas (Blondeau et al. 1999). Nonpregnant rats also normally increase β-cell mass by 40% by replication between 3 and 12 months of age; however, CR rats do not show this increase, resulting in reduced insulin secretion (Garofano et al. 1999).

CR fetuses have elevated glucocorticoid concentrations, which has been proposed as a mechanism for the observed β-cell dysfunction (Blondeau et al. 2001). Studies on pancreas development in vitro and in glucocorticoid receptor knockout mice show that glucocorticoids impair normal β-cell differentiation and lower Pdx-1 expression (Gesina et al. 2006; Gesina et al. 2004). In normal rat fetuses, there is a negative correlation between plasma corticosterone and fetal weight, as well as pancreatic insulin content (Blondeau et al. 2001). When CR rat dams are subjected to adrenalectomy and then exogenously supplemented with normal levels of corticosterone, fetal β-cell fraction and mass are restored despite CR (Blondeau et al. 2001; Lesage et al. 2001). Fetal body weight and pancreas weight are still reduced (Blondeau et al. 2001; Lesage et al. 2001), indicating that elevated glucocorticoids have a β-cell specific effect, while malnutrition still impacts other aspects of fetal development.

Low protein diet model

Feeding dams a low protein (LP) isocaloric diet (8% vs. 20% dietary protein) throughout gestation causes IUGR and lowers fetal and postnatal pancreas weight, β-cell mass, and islet size (Table 2) (Boujendar et al. 2002; Dahri et al. 1991; Petrik et al. 1999b; Snoeck et al. 1990). In contrast to CR offspring, β-cell differentiation progresses normally in LP fetuses (Dumortier et al. 2007). However, at E21.5 islet cell proliferation is lower due to a longer G1 phase, and apoptosis is increased (Boujendar et al. 2002; Petrik et al. 1999b). These changes are associated with lower islet IGF-II expression, which if over-expressed can cause β-cell hyperplasia (Petrik et al. 1998; Petrik et al. 1999a; Petrik et al. 1999b). Moreover, these effects may be influenced by lower islet vascularity and depressed expression of VEGF and VEGF receptor 2, reminiscent of the UAL model (Boujendar et al. 2003; Dumortier et al. 2007; Snoeck et al. 1990).

One study attempted to separate temporal effects by feeding the LP diet during either gestation or lactation or throughout both periods (Berney et al. 1997). In all circumstances, protein restriction reduced β-cell area and caused islets to be irregularly shaped in weanlings. However, postnatal protein restriction caused greater reductions inβ-cell and islet numbers, fitting temporally with the postnatal β-cell expansion and isletogenesis. In addition, feeding an LP diet during just the last week of gestation had a greater impact on fetal β-cell mass than LP feeding throughout gestation, indicating that the dam is able to compensate for protein restriction to some extent when it is initiated earlier (Dumortier et al. 2007). These data indicate that timing of protein restriction relative to pancreas development is critical for determining β-cell outcomes in offspring.

Impaired islet insulin responsiveness to amino acids and theophylline is observed in vitro in LP fetal islets; however, neither control nor LP fetal islets (E21.5) responded to glucose (Cherif et al. 1998; Cherif et al. 1996; Dahri et al. 1991). As adults, LP rats demonstrate impaired glucose tolerance but do not develop diabetes (Dahri et al. 1991). In postnatal LP islets, β-cell metabolism is decreased, likely lowering β-cell response to insulin secretagogues (Goosse et al. 2009; Sener et al. 1996).

Additional studies have shown that LP islets have increased nitric oxide production in unstimulated islets (Goosse et al. 2009) and increased sensitivity to nitric oxide- and IL-1β-induced apoptosis (Merezak et al. 2001). The transcription factor growth arrest and DNA damage inducible-protein 153 (GADD153) mRNA and protein expression are increased in LP islets, implicating ER stress pathways in β-cell dysfunction (Goosse et al. 2009). Furthermore, LP islets develop an imbalance in antioxidant enzyme expression, likely increasing susceptibility to oxidative stress (Theys et al. 2009).

Plasma taurine is lower in LP dams and their fetuses. Taurine has many physiological functions, including serving as an antioxidant (Huxtable 1992). It is considered an essential amino acid for fetal and neonatal development, because in vivo synthesis is inadequate at these ages (Aerts and Van Assche 2002; Huxtable 1992; Sturman 1993). Taurine supplementation of LP dams during pregnancy normalizes islet responsiveness, IGF-II, and vascularity, as well as β-cell proliferation, apoptosis, and mass (Boujendar et al. 2003; Boujendar et al. 2002; Cherif et al. 1998). However, fetal and pup body weights are not corrected (Boujendar et al. 2002). Thus, LP feeding appears to have β-cell specific effects, which may be caused by a taurine deficiency rather than global protein malnutrition.

Sheep Models of IUGR

Hyperthermia-induced Placental Insufficiency

Pregnant ewes chronically exposed to elevated ambient temperatures from early to late gestation have fetuses that are growth restricted close to term (135 dGA, term ~147) (Bell et al. 1987; Regnault et al. 2002; Regnault et al. 1999). Smaller placentae with a decreased capacity to transport oxygen and nutrients from the mother to the fetus cause the fetus to become hypoxemic and hypoglycemic (Table 2) (de Vrijer et al. 2004; Limesand et al. 2004; Limesand et al. 2007; Thureen et al. 1992), causing growth restriction in the hyperthermia-induced placental insufficiency (HT-PI) model. Biometric parameters and fetal weight begin to diverge from normal after 70 dGA, just after the apex of placental growth, and worsen as gestation continues, demonstrating that the placenta is unable to adequately supply fetal demands for growth (Galan et al. 1999; Regnault et al. 2003; Regnault et al. 2002).

Although asymmetric fetal growth is apparent, fetal adaptations appear to target the β-cells to a great extent (Limesand et al. 2005). At 133 dGA (0.9 of gestation), HT-PI pancreas weight parallels the fetal growth reduction (−59%), but β-cell mass is lower (−76%) due to fewer β-cells (Limesand et al. 2005). This is the result of an extended cell cycle, because β-cell mitosis is 72% lower in HT-PI islets (Limesand et al. 2005). β-cell differentiation may also be impaired, because β-cells in the extra-islet compartment, which might represent newly formed β-cells, are decreased in the HT-PI pancreas; however, changes in isletogenesis could also explain this difference (Limesand et al. 2005). Together, these results indicate that placental insufficiency decreases the number of β-cells (Limesand et al. 2005).

HT-PI fetuses also have impaired insulin secretion, measured by GSIS and glucose potentiated arginine-induced insulin secretion (GPAIS; Table 1) (Limesand et al. 2007; Limesand et al. 2006). Glucose-stimulated insulin release by fetal islets, expressed as a fraction of total insulin content, is greater in HT-PI islets than controls, but the amount of insulin released per HT-PI islet is significantly less due to lower insulin contents (82%). HT-PI islets also demonstrate a deficiency in glucose metabolism; they are unresponsive to glucose enhanced oxidative metabolism, but glucose utilization rates are intact (Limesand et al. 2006). Therefore, IUGR islets have impaired insulin secretion due to reduced insulin biosynthesis and storage, which might be partially in response to impaired oxidative metabolism. However, IUGR islets appear to compensate for these deficits to some extent by augmenting their capacity to release insulin.

Placental insufficiency causes fetal hypoglycemia and hypoxemia, both of which can independently lower insulin. Chronic hypoglycemia without hypoxemia, which is discussed as a separate model below, results in moderate impairment of insulin secretion. Conversely, when glucose is intravenously replaced in HT-PI fetuses for two weeks, it is not well tolerated and fails to correct insulin secretion (Rozance et al. 2009b), confirming that hypoxemia in addition to hypoglycemia contributes to the β-cell dysfunction. The suppressive effects of hypoxemia on β-cell function may be directly related to the elevation in catecholamines. Acute bouts of asphyxia cause plasma norepinephrine concentrations to rise in fetal sheep, and via the α2-adrenergic receptors, norepinephrine suppresses insulin release (Cheung 1990; Jackson et al. 2000; Milley 1997). In human fetuses, norepinephrine concentrations are also increased during hypoxia and are higher in IUGR fetuses (Greenough et al. 1990; Paulick et al. 1985). We have shown that GSIS can be restored in HT-PI fetuses with adrenergic receptor blockade (Leos et al. 2010). This recovery in insulin secretion happens even though fewer β-cells are present, suggesting that the β-cells are hyper-responsive, which is also observed in the isolated islets and persists in the HT-PI lambs at P8 (Limesand et al. unpublished). These findings could begin to explain the mismatch in insulin secretion and glucose disposal rate observed in IUGR infants (Bazaes et al. 2003).

Uterine Carunclectomy Model of Placental Restriction

Another well-established sheep model of IUGR is produced by removing most of the endometrial caruncles from the uterus prior to pregnancy, resulting in placental restriction (UC-PR) (Robinson et al. 1979). In contrast to humans and rodents, sheep and other ruminants have a cotyledonary placenta that consists of many placentomes. These are discrete units of maternal-fetal interface for gas and nutrient exchange formed by the maternal caruncle and the fetal cotyledon (chorion). Thus, removing the endometrial caruncles lowers the number of sites for placentation in the subsequent pregnancy and reduces placenta size and function (Robinson et al. 1979). UC-PR fetuses are smaller compared to controls, hypoxemic (−23 to 35%), and hypoglycemic (−15 to 41%) in late gestation (Table 2) (Owens et al. 1989; Owens et al. 2007; Robinson et al. 1979). Catecholamine (Simonetta et al. 1997) and cortisol (Phillips et al. 1996) concentrations are also increased during late gestation.

In UC-PR fetuses, Owens and colleagues have shown that fetal hypoxemia and hypoglycemia are associated with deficiencies in acute β-cell responsiveness, demonstrated by decreased insulin secretion during intravenous glucose tolerance tests (IVGTT; Table 1) and intravenous arginine stimulation tests (IVAST; Table 1) (Owens et al. 2007). Importantly, the loss of acute insulin secretion is a hallmark of T2DM (Kahn et al. 2001; Ward et al. 1984). IVGTT and IVAST tests measure only first phase insulin secretion, while the GPAIS test used in the HT-PI model measures maximal insulin release (Robertson 2007). Therefore, reductions in insulin secretion may be even more pronounced in UC-PR fetuses than indicated by the IVGTT/IVAST tests. No differences are found in β-cell area or mass in UC-PR fetuses compared to controls (Gatford et al. 2008). However, fetal weight does positively correlate with β-cell mass, indicating a similar, though attenuated, response compared to HT-PI fetuses.

UC-PR offspring also suffer postnatal consequences. Young lambs and young adult sheep exhibit impaired glucose tolerance due to β-cell insufficiencies that are associated with reduced body weight or thinness at birth (De Blasio et al. 2007). In young IUGR lambs, IVGTT reveals depressed insulin secretion during the first 15 minutes and a marginally lower insulin disposition that appears to be spared by improved insulin sensitivity (De Blasio et al. 2007). In adulthood, however, birth weight is negatively correlated with β-cell mass in males but positively correlated with glucose disposition (Table 1), suggesting that a greater number of β-cells are required to maintain glucose homeostasis in UC-PR adults (Gatford et al. 2008). Insulin-like growth factors I and II, determinants for β-cell growth, are elevated in the pancreas of month-old UC-PR lambs, and these growth factors are postulated to be associated with neonatal catch-up growth (Gatford et al. 2008). The expression of the voltage-gated calcium channel α1D is decreased and positively correlated with β-cell function, identifying a candidate gene for β-cell dysfunction in the stimulus-secretion coupling (Gatford et al. 2008).

Chronic Hypoglycemia

Experimental hypoglycemia (HG) can be established in fetal sheep to measure β-cell outcomes in a system relatively independent of other common complications usually associated with placental insufficiency, such as hypoxemia. A maternal insulin infusion lowers both maternal and fetal arterial plasma glucose concentrations by about 50% and is maintained for 10–14 days (DiGiacomo and Hay 1990). Maternal insulin does not cross the placenta, and therefore, fetal insulin concentrations decrease markedly in response to hypoglycemia. Uterine and umbilical blood flows are maintained, as are fetal oxygen, oxygen uptake, and amino acid uptake, but fetuses are smaller than control fetuses (Table 2) (DiGiacomo and Hay 1990; Limesand et al. 2009). Other changes relevant to β-cell function include alterations in fetal plasma amino acid profiles, with notable increases in taurine and lysine. Cortisol is also elevated, but catecholamines remain normal (Limesand and Hay 2003; Rozance et al. 2008).

Fetal GSIS and GPAIS are lower in HG fetuses (Carver et al. 1996; Limesand and Hay 2003). Non-linear modeling of insulin secretion during a square-wave hyperglycemic clamp reveals a delay in insulin release (Limesand and Hay 2003). Morphological analysis of the endocrine pancreas shows that β-cell mass and insulin content are maintained, indicating that the blunted insulin secretion is due to a functional β-cell defect. In vitro, despite an ability to utilize and oxidize glucose normally, glucose and amino acid stimulated insulin secretion are completely absent, indicating an intrinsic β-cell defect in insulin granule exocytosis (Rozance et al. 2006; Rozance et al. 2007). Therefore, chronic HG blunts insulin secretion as a result of deficiencies in later steps of stimulus-secretion coupling after glucose metabolism, membrane depolarization, and calcium entry. The β-cell impairment in chronically HG fetuses is clearly distinct from the HT-PI model, showing that hypoglycemia alone can create islet dysfunction during late gestation.

Five days of euglycemic correction after 14 days of fetal hypoglycemia normalizes insulin concentrations during the euglycemic and hyperglycemic clamp periods. However, the time required to reach maximal insulin concentrations remains delayed, and GPAIS does not recover (Limesand and Hay 2003). These data confirm that chronic hypoglycemia can cause persistent impairments in β-cell function, similar to the findings in the UC-PR model.

CONSEQUENCES TO β-CELLS IN IUGR MODELS

Animal models of IUGR provide useful insights into potential mechanisms for β-cell programming in response to nutrient or oxygen deprivation (Figure 1). Advantages of rats as a model species include a short gestation period and lifespan, making them useful for studying adulthood and multigenerational effects of IUGR. Moreover, pancreas development in rodents progresses in relatively discrete stages (Table 3), which allows us to link β-cell defects to distinct developmental transitions. For example, CR throughout gestation targets β-cell differentiation, whereas UAL in late gestation targets β-cell maturation and proliferation (Table 2). Other factors contribute to these outcomes; a primary factor in CR rats appears to be elevated glucocorticoids, whereas epigenetic changes that lower Pdx-1 transcription are central to the UAL β-cell dysfunction. Offspring from all three rat models exhibit reduced β-cell proliferation, which might reflect vascular deficiencies and/or lower growth factor concentrations. Defects in β-cell metabolism have also been identified in UAL and LP offspring, indicating that inefficient insulin secretion responsiveness can continue to take a toll postnatally. Overall, the rodent models show that impaired β-cell function can persist long after the intrauterine complications, and these deficiencies impact a variety of aspects coordinating β-cell mass and function.

The fetal sheep has proven to be a valuable model for studying the pathogenesis of IUGR and will continue to extend our knowledge of how IUGR alters the multifocal pancreas development pattern found in both sheep and humans (Table 3). Of the three ovine models, HT-PI results in the greatest reduction β-cell mass. The UC-PR model causes a more moderate IUGR (Table 2), but β-cell mass is still correlated with fetal weight. This correlation between the degree of IUGR and the reduction in β-cell mass is reminiscent of the pattern seen in the human studies: severe IUGR cases have lower β-cell mass (Van Assche et al. 1977), but there is no evidence for this in moderate IUGR (Beringue et al. 2002). Timing of fetal nutrient restriction is also a factor. HT-PI begins after mid gestation and causes lower β-cell mass than the HG and UC-PR models, for which nutrient restriction occurs only during the final 20% of gestation. The degree of fetal hypoglycemia is similar in the HT-PI and HG models, but islet responses are different, further highlighting the importance of discrepancies in the duration and timing of nutrient restriction. However, similar to the rat models, IUGR in sheep impairs a variety of aspects important for β-cell function, including proliferation, insulin storage, glucose metabolism, or exocytosis (Figure 1).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN IUGR RESEARCH

While there is strong evidence for an association between human IUGR and β-cell programming, there is a paucity of data on insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and β-cell function in truly IUGR infants. Therefore, another prospective study with assessments throughout lifespan is needed to verify the results of Mericq and colleagues (Soto et al. 2003). In addition to metabolic and morphometric evaluations, it will be critical to include measurements of initiators of β-cell dysfunction described in animal models (e.g., catecholamine and glucocorticoid concentrations). Furthermore, we have little knowledge of β-cell mass in IUGR patients at birth or throughout lifespan. These data could be obtained from autopsy studies, but in vivo real-time measurements of β-cell mass would obviously be more advantageous. The emerging technologies of in vivo imaging and quantification of β-cell mass (Souza et al. 2006; Sweet et al. 2004) will be useful for this purpose and could be performed concurrently with a complete in vivo assessment.

Future research is also needed to develop interventions that can improve outcomes in IUGR patients by rescuing β-cell function and preventing obesity, insulin resistance, and T2DM. Nutritional interventions in mothers at risk for or with IUGR fetuses have shown mixed results, in some cases worsening perinatal growth and increasing mortality (Harding and Charlton 1989; Kramer and Kakuma 2003; Rush et al. 1980). Thus, interventions should be pursued only after appropriate animal testing. The fetal sheep is an excellent model for this purpose, because fetal conditions can be precisely regulated for discrete periods of gestation to mimic features of placental insufficiency induced IUGR and to test the impact of potential treatments on fetal β-cell function and metabolism. Using the catheterized fetal sheep preparation, the impact of chronic supplementation of fetal glucose (Rozance et al. 2009b), amino acids (Rozance et al. 2009a), IGF-1 (Eremia et al. 2007), and insulin (Carson et al. 1980) on fetal metabolism has been measured in control and IUGR fetuses. These studies should be expanded to optimize conditions for IUGR fetuses, with the ultimate goal of identifying treatments that that can be administered through the mother to rescue fetal β-cell function and mass.

CONCLUSIONS

IUGR is associated with impaired glucose tolerance and T2DM later in life, and there is evidence that insulin secretion defects contribute to these outcomes. Animal models of IUGR are critical for defining potential mechanisms of β-cell dysfunction. They have thus far demonstrated that β-cell dysfunction can be reached by multiple mechanisms (Figure 1), likely depending on the type, timing, and duration of fetal malnutrition and how these factors coincide with stages of pancreas development. There are currently few data from which to determine which, if any, of the identified mechanisms may cause the insulin secretion defect in humans, highlighting the need for more human studies. Animal studies will continue to be important to expand and refine our knowledge of mechanisms, as well as to test potential therapies that may ultimately be used to improve outcomes in human IUGR patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Award Number R01DK084842 (Principle Investigator S.W. Limesand) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. A.S. Green was supported by an NIH Institutional Training Grant (Interdisciplinary Training in Cardiovascular Research, HL07249) and F32DK088514 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. P.J. Rozance was supported by an American Diabetes Association Junior Faculty Award (7-08-JF-51) and a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Career Development Award (1K08HD060688-01). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adam PA, Teramo K, Raiha N, Gitlin D, Schwartz R. Human fetal insulin metabolism early in gestation. Response to acute elevation of the fetal glucose concentration and placental tranfer of human insulin-I-131. Diabetes. 1969;18:409–416. doi: 10.2337/diab.18.6.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerts L, Van Assche FA. Taurine and taurine-deficiency in the perinatal period. J Perinat Med. 2002;30:281–286. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2002.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldoretta PW, Carver TD, Hay WW., Jr Maturation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in fetal sheep. Biol Neonate. 1998;73:375–386. doi: 10.1159/000014000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril I, Blondeau B, Duchene B, Czernichow P, Breant B. Decreased beta-cell proliferation impairs the adaptation to pregnancy in rats malnourished during perinatal life. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:215–223. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993;36:62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazaes RA, Alegria A, Pittaluga E, Avila A, Iniguez G, Mericq V. Determinants of insulin sensitivity and secretion in very-low-birth-weight children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1267–1272. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazaes RA, Salazar TE, Pittaluga E, Pena V, Alegria A, Iniguez G, Ong KK, Dunger DB, Mericq MV. Glucose and lipid metabolism in small for gestational age infants at 48 hours of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:804–809. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AW, Wilkening RB, Meschia G. Some aspects of placental function in chronically heat-stressed ewes. J Dev Physiol. 1987;9:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beringue F, Blondeau B, Castellotti MC, Breant B, Czernichow P, Polak M. Endocrine pancreas development in growth-retarded human fetuses. Diabetes. 2002;51:385–391. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berney DM, Desai M, Palmer DJ, Greenwald S, Brown A, Hales CN, Berry CL. The effects of maternal protein deprivation on the fetal rat pancreas: major structural changes and their recuperation. J Pathol. 1997;183:109–115. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<109::AID-PATH1091>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan A, Itoh N, Kato S, Thiery JP, Czernichow P, Bellusci S, Scharfmann R. Fgf10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development. 2001;128:5109–5117. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau B, Garofano A, Czernichow P, Breant B. Age-dependent inability of the endocrine pancreas to adapt to pregnancy: a long-term consequence of perinatal malnutrition in the rat. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4208–4213. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.9.6960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau B, Lesage J, Czernichow P, Dupouy JP, Breant B. Glucocorticoids impair fetal beta-cell development in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E592–E599. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.3.E592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocian-Sobkowska J, Zabel M, Wozniak W, Surdyk-Zasada J. Polyhormonal aspect of the endocrine cells of the human fetal pancreas. Histochem Cell Biol. 1999;112:147–153. doi: 10.1007/s004180050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujendar S, Arany E, Hill D, Remacle C, Reusens B. Taurine supplementation of a low protein diet fed to rat dams normalizes the vascularization of the fetal endocrine pancreas. J Nutr. 2003;133:2820–2825. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujendar S, Reusens B, Merezak S, Ahn MT, Arany E, Hill D, Remacle C. Taurine supplementation to a low protein diet during foetal and early postnatal life restores a normal proliferation and apoptosis of rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2002;45:856–866. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens L, Lu WG, De Krijger R. Proliferation and differentiation in the human fetal endocrine pancreas. Diabetologia. 1997;40:398–404. doi: 10.1007/s001250050693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson BS, Philipps AF, Simmons MA, Battaglia FC, Meschia G. Effects of a sustained insulin infusion upon glucose uptake and oxygenation of the ovine fetus. Pediatr Res. 1980;14:147–152. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198002000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver TD, Anderson SM, Aldoretta PW, Hay WW., Jr Effect of low-level basal plus marked “pulsatile” hyperglycemia on insulin secretion in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E865–E871. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.5.E865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherif H, Reusens B, Ahn MT, Hoet JJ, Remacle C. Effects of taurine on the insulin secretion of rat fetal islets from dams fed a low-protein diet. J Endocrinol. 1998;159:341–348. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherif H, Reusens B, Dahri S, Remacle C, Hoet JJ. Stimulatory effects of taurine on insulin secretion by fetal rat islets cultured in vitro. J Endocrinol JID - 0375363. 1996;151:501–506. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1510501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY. Fetal adrenal medulla catecholamine response to hypoxia-direct and neural components. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:R1340–1346. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.6.R1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole L, Anderson M, Antin PB, Limesand SW. One process for pancreatic beta-cell coalescence into islets involves an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Endocrinol. 2009;203:19–31. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole L, Anderson MJ, Leos RA, Jensen J, Limesand SW. Progression of Endocrine Cell Formation in the Sheep Pancreas. Diabetes 67th Scientific Session Abstract Book. 2007:1683-P. [Google Scholar]

- Colle E, Schiff D, Andrew G, Bauer CB, Fitzhardinge P. Insulin responses during catch-up growth of infants who were small for gestational age. Pediatrics JID - 0376422. 1976;57:363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JE, Leonard JV. Hyperinsulinism in asphyxiated and small-for-dates infants with hypoglycaemia. Lancet. 1984;2:311–313. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JE, Leonard JV, Teale D, Marks V, Williams DM, Kennedy CR, Hall MA. Hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in small for dates babies. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:1118–1120. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.10.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams J. Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther NJ, Trusler J, Cameron N, Toman M, Gray IP. Relation between weight gain and beta-cell secretory activity and non-esterified fatty acid production in 7-year-old African children: results from the Birth to Ten study. Diabetologia. 2000;43:978–985. doi: 10.1007/s001250051479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahri S, Snoeck A, Reusens-Billen B, Remacle C, Hoet JJ. Islet function in offspring of mothers on low-protein diet during gestation. Diabetes. 1991;40(Suppl 2):115–120. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.2.s115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, McMillen IC, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Placental restriction of fetal growth increases insulin action, growth, and adiposity in the young lamb. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1350–1358. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Prins FA, Van Assche FA. Intrauterine growth retardation and development of endocrine pancreas in the experimental rat. Biol Neonate. 1982;41:16–21. doi: 10.1159/000241511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vrijer B, Regnault TR, Wilkening RB, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Placental uptake and transport of ACP, a neutral nonmetabolizable amino acid, in an ovine model of fetal growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E1114–1124. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00259.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Bosque-Plata L, Lin J, Horikawa Y, Schwarz PE, Cox NJ, Iwasaki N, Ogata M, Iwamoto Y, German MS, Bell GI. Mutations in the coding region of the neurogenin 3 gene (NEUROG3) are not a common cause of maturity-onset diabetes of the young in Japanese subjects. Diabetes. 2001;50:694–696. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiacomo JE, Hay WW., Jr Fetal glucose metabolism and oxygen consumption during sustained hypoglycemia. Metabolism. 1990;39:193–202. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90075-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumortier O, Blondeau B, Duvillie B, Reusens B, Breant B, Remacle C. Different mechanisms operating during different critical time-windows reduce rat fetal beta cell mass due to a maternal low-protein or low-energy diet. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2495–2503. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economides DL, Proudler A, Nicolaides KH. Plasma insulin in appropriate- and small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1091–1094. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremia SC, de Boo HA, Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Harding JE. Fetal and amniotic insulin-like growth factor-I supplements improve growth rate in intrauterine growth restriction fetal sheep. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2963–2972. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrazzi E, Bozzo M, Rigano S, Bellotti M, Morabito A, Pardi G, Battaglia FC, Galan HL. Temporal sequence of abnormal Doppler changes in the peripheral and central circulatory systems of the severely growth-restricted fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19:140–146. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2002.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan DE, Moore VM, Godsland IF, Cockington RA, Robinson JS, Phillips DI. Fetal growth and the physiological control of glucose tolerance in adults: a minimal model analysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E700–706. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.4.E700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan HL, Hussey MJ, Barbera A, Ferrazzi E, Chung M, Hobbins JC, Battaglia FC. Relationship of fetal growth to duration of heat stress in an ovine model of placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1278–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofano A, Czernichow P, Breant B. In utero undernutrition impairs rat beta-cell development. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1231–1234. doi: 10.1007/s001250050812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofano A, Czernichow P, Breant B. Beta-cell mass and proliferation following late fetal and early postnatal malnutrition in the rat. Diabetologia. 1998a;41:1114–1120. doi: 10.1007/s001250051038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofano A, Czernichow P, Breant B. Postnatal somatic growth and insulin contents in moderate or severe intrauterine growth retardation in the rat. Biol Neonate. 1998b;73:89–98. doi: 10.1159/000013964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofano A, Czernichow P, Breant B. Effect of ageing on beta-cell mass and function in rats malnourished during the perinatal period. Diabetologia. 1999;42:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s001250051219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatford KL, Mohammad SN, Harland ML, De Blasio MJ, Fowden AL, Robinson JS, Owens JA. Impaired beta-cell function and inadequate compensatory increases in beta-cell mass after intrauterine growth restriction in sheep. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5118–5127. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier BR, Brun T, Sarret EJ, Ishihara H, Schaad O, Descombes P, Wollheim CB. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis reveals PDX1 as an essential regulator of mitochondrial metabolism in rat islets. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31121–31130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerich JE. The genetic basis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: impaired insulin secretion versus impaired insulin sensitivity. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:491–503. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.4.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesina E, Blondeau B, Milet A, Le NI, Duchene B, Czernichow P, Scharfmann R, Tronche F, Breant B. Glucocorticoid signalling affects pancreatic development through both direct and indirect effects. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2939–2947. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0449-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesina E, Tronche F, Herrera P, Duchene B, Tales W, Czernichow P, Breant B. Dissecting the role of glucocorticoids on pancreas development. Diabetes. 2004;53:2322–2329. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosse K, Bouckenooghe T, Balteau M, Reusens B, Remacle C. Implication of nitric oxide in the increased islet-cells vulnerability of adult progeny from protein-restricted mothers and its prevention by taurine. J Endocrinol. 2009;200:177–187. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1607–1611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenough A, Nicolaides KH, Lagercrantz H. Human fetal sympathoadrenal responsiveness. Early Hum Dev. 1990;23:9–13. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(90)90124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham JN, Crutchlow MF, Desai BM, Simmons RA, Stoffers DA. Exendin-4 normalizes islet vascularity in intrauterine growth restricted rats: potential role of VEGF. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:42–46. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a282a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JE, Charlton V. Treatment of the growth-retarded fetus by augmentation of substrate supply. Semin Perinatol. 1989;13:211–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe FM, Thornton PS, Wanner LA, Steinkrauss L, Simmons RA, Stanley CA. Clinical features and insulin regulation in infants with a syndrome of prolonged neonatal hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr. 2006;148:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman PL, Cutfield WS, Robinson EM, Bergman RN, Menon RK, Sperling MA, Gluckman PD. Insulin resistance in short children with intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:402–406. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniguez G, Ong K, Bazaes R, Avila A, Salazar T, Dunger D, Mericq V. Longitudinal changes in insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin sensitivity, and secretion from birth to age three years in small-for-gestational-age children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4645–4649. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson BT, Piasecki GJ, Cohn HE, Cohen WR. Control of fetal insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R2179–R2188. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CB, Storgaard H, Dela F, Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Vaag AA. Early differential defects of insulin secretion and action in 19-year-old caucasian men who had low birth weight. Diabetes. 2002;51:1271–1280. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. Gene regulatory factors in pancreatic development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:176–200. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Heller RS, Funder-Nielsen T, Pedersen EE, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Madsen OD, Serup P. Independent development of pancreatic alpha- and beta-cells from neurogenin3-expressing precursors: a role for the notch pathway in repression of premature differentiation. Diabetes. 2000;49:163–176. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE, Montgomery B, Howell W, Ligueros-Saylan M, Hsu CH, Devineni D, McLeod JF, Horowitz A, Foley JE. Importance of early phase insulin secretion to intravenous glucose tolerance in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab JID - 0375362. 2001;86:5824–5829. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK, Boyko EJ, Bergman RN, Schwartz MW, Neifing JL, Ward WK, Beard JC, Palmer JP. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in human subjects. Evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes. 1993;42:1663–1672. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassem SA, Ariel I, Thornton PS, Scheimberg I, Glaser B. Beta-cell proliferation and apoptosis in the developing normal human pancreas and in hyperinsulinism of infancy. Diabetes. 2000;49:1325–1333. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.8.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kervran A, Randon J. Development of insulin release by fetal rat pancreas in vitro: effects of glucose, amino acids, and theophylline. Diabetes. 1980;29:673–678. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.9.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kervran A, Randon J, Girard JR. Dynamics of glucose-induced plasma insulin increase in the rat fetus at different stages of gestation. Effects of maternal hypothermia and fetal decapitation. Biol Neonate. 1979;35:242–248. doi: 10.1159/000241180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Energy and protein intake in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(4):Art No.: CD00032. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000032. 00010.01002/14651858.CD14600032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert E, Cleaver O, Melton D. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science. 2001;294:564–567. doi: 10.1126/science.1064344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leos RA, Anderson MJ, Chen X, Pugmire JP, Anderson KA, Limesand SW. Chronic exposure to elevated norepinephrine suppresses insulin secretion in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00494.2009. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Blondeau B, Grino M, Breant B, Dupouy JP. Maternal undernutrition during late gestation induces fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids and intrauterine growth retardation, and disturbs the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in the newborn rat. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1692–1702. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Johnson MS, Goran MI. Effects of low birth weight on insulin resistance syndrome in caucasian and African-American children. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:2035–2042. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.12.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Chen H, Epstein PN. Metallothionein protects islets from hypoxia and extends islet graft survival by scavenging most kinds of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:765–771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Hay WW., Jr Adaptation of ovine fetal pancreatic insulin secretion to chronic hypoglycaemia and euglycaemic correction. J Physiol. 2003;547(1):95–105. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Jensen J, Hutton J, Hay WW., Jr Diminished beta-cell replication contributes to reduced beta-cell mass in fetal sheep with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2005;288:R1297–R1305. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00494.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Regnault TR, Hay WW., Jr Characterization of glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) in the ovine placenta of normal and growth restricted fetuses. Placenta. 2004;25:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Brown LD, Hay WW., Jr Effects of chronic hypoglycemia and euglycemic correction on lysine metabolism in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E879–887. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90832.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Smith D, Hay WW., Jr Increased insulin sensitivity and maintenance of glucose utilization rates in fetal sheep with placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1716–1725. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00459.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Rozance PJ, Zerbe GO, Hutton JC, Hay WW., Jr Attenuated insulin release and storage in fetal sheep pancreatic islets with intrauterine growth restriction. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1488–1497. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merezak S, Hardikar AA, Yajnik CS, Remacle C, Reusens B. Intrauterine low protein diet increases fetal beta-cell sensitivity to NO and IL-1 beta: the protective role of taurine. J Endocrinol. 2001;171:299–308. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1710299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mericq V, Ong KK, Bazaes R, Pena V, Avila A, Salazar T, Soto N, Iniguez G, Dunger DB. Longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion from birth to age three years in small- and appropriate-for-gestational-age children. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2609–2614. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milley JR. Ovine fetal metabolism during norepinephrine infusion. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E336–E347. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.2.E336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina RD, Carver TD, Hay WW., Jr Ontogeny of insulin effect in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:654–660. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199311000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome CA, Shiell AW, Fall CH, Phillips DI, Shier R, Law CM. Is birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism?--A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2003;20:339–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini U, Hubinont C, Santolaya J, Fisk NM, Rodeck CH. Effects of fetal intravenous glucose challenge in normal and growth retarded fetuses. Horm Metab Res. 1990;22:426–430. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto MA. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:155–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova G, Jabs N, Konstantinova I, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Sorokin L, Fassler R, Gu G, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, et al. The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and Beta cell proliferation. Dev Cell. 2006;10:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard GA, Jensen JN, Jensen J. FGF10 signaling maintains the pancreatic progenitor cell state revealing a novel role of Notch in organ development. Dev Biol. 2003;264:323–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offield MF, Jetton TL, Labosky PA, Ray M, Stein RW, Magnuson MA, Hogan BL, Wright CV. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata ES, Bussey ME, Finley S. Altered gas exchange, limited glucose and branched chain amino acids, and hypoinsulinism retard fetal growth in the rat. Metabolism. 1986;35:970–977. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KK, Ahmed ML, Emmett PM, Preece MA, Dunger DB. Association between postnatal catch-up growth and obesity in childhood: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:967–971. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7240.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Falconer J, Robinson JS. Glucose metabolism in pregnant sheep when placental growth is restricted. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R350–R357. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.2.R350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JA, Gatford KL, De Blasio MJ, Edwards LJ, McMillen IC, Fowden AL. Restriction of placental growth in sheep impairs insulin secretion but not sensitivity before birth. J Physiol. 2007;584:935–949. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Stoffers DA, Nicholls RD, Simmons RA. Development of type 2 diabetes following intrauterine growth retardation in rats is associated with progressive epigenetic silencing of Pdx1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2316–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI33655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulick R, Kastendieck E, Wernze H. Catecholamines in arterial and venous umbilical blood: placental extraction, correlation with fetal hypoxia, and transcutaneous partial oxygen tension. J Perinat Med. 1985;13:31–42. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1985.13.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterside IE, Selak MA, Simmons RA. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation in hepatic mitochondria in growth-retarded rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E1258–E1266. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00437.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrik J, Arany E, McDonald TJ, Hill DJ. Apoptosis in the pancreatic islet cells of the neonatal rat is associated with a reduced expression of insulin-like growth factor II that may act as a survival factor. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2994–3004. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrik J, Pell JM, Arany E, McDonald TJ, Dean WL, Reik W, Hill DJ. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-II in transgenic mice is associated with pancreatic islet cell hyperplasia. Endocrinology. 1999a;140:2353–2363. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.5.6732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrik J, Reusens B, Arany E, Remacle C, Coelho C, Hoet JJ, Hill DJ. A low protein diet alters the balance of islet cell replication and apoptosis in the fetal and neonatal rat and is associated with a reduced pancreatic expression of insulin-like growth factor-II. Endocrinology. 1999b;140:4861–4873. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.10.7042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipps AF, Carson BS, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Insulin secretion in fetal and newborn sheep. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:E467–E474. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.5.E467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ID, Simonetta G, Owens JA, Robinson JS, Clarke IJ, McMillen IC. Placental restriction alters the functional development of the pituitary-adrenal axis in the sheep fetus during late gestation. Pediatr Res. 1996;40:861–866. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199612000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pictet R, Rutter WJ, Geiger SR. Handbook of Physiology Section 7: Endocrinology. Washington D.C: American Physiological Society; 1972a. Development of the embryonic endocrine pancreas; pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pictet RL, Clark WR, Williams RH, Rutter WJ. An ultrastructural analysis of the developing embryonic pancreas. Dev Biol. 1972b;29:436–467. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(72)90083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper K, Brickwood S, Turnpenny LW, Cameron IT, Ball SG, Wilson DI, Hanley NA. Beta cell differentiation during early human pancreas development. J Endocrinol. 2004;181:11–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1810011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platz E, Newman R. Diagnosis of IUGR: traditional biometry. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:140–147. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polak M, Bouchareb-Banaei L, Scharfmann R, Czernichow P. Early pattern of differentiation in the human pancreas. Diabetes. 2000;49:225–232. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Hales CN, Bleker OP. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnault TR, de Vrijer B, Galan HL, Davidsen ML, Trembler KA, Battaglia FC, Wilkening RB, Anthony RV. The relationship between transplacental O2 diffusion and placental expression of PlGF, VEGF and their receptors in a placental insufficiency model of fetal growth restriction. J Physiol. 2003;550:641–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.039511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnault TR, Galan HL, Parker TA, Anthony RV. Placental development in normal and compromised pregnancies. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl A):S119–29. S119–S129. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnault TR, Orbus RJ, Battaglia FC, Wilkening RB, Anthony RV. Altered arterial concentrations of placental hormones during maximal placental growth in a model of placental insufficiency. J Endocrinol. 1999;162:433–442. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1620433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RP. Defective insulin secretion in NIDDM: integral part of a multiplier hypothesis. J Cell Biochem. 1992;48:227–233. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240480302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RP. Estimation of beta-cell mass by metabolic tests: necessary, but how sufficient? Diabetes. 2007;56:2420–2424. doi: 10.2337/db07-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RP, Harmon JS. Diabetes, glucose toxicity, and oxidative stress: A case of double jeopardy for the pancreatic islet beta cell. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JS, Kingston EJ, Jones CT, Thorburn GD. Studies on experimental growth retardation in sheep. The effect of removal of a endometrial caruncles on fetal size and metabolism. J Dev Physiol. 1979;1:379–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]