The combination of poorly controlled diabetes, acute liver injury with marked elevation in serum aminotransferases, and the characteristic histological changes on liver biopsy are diagnostic of glycogenic hepatopathy. A similar condition was described by Mauriac in 1930, characterized by growth retardation, hepatomegaly, Cushingoid features, and delayed puberty (1).

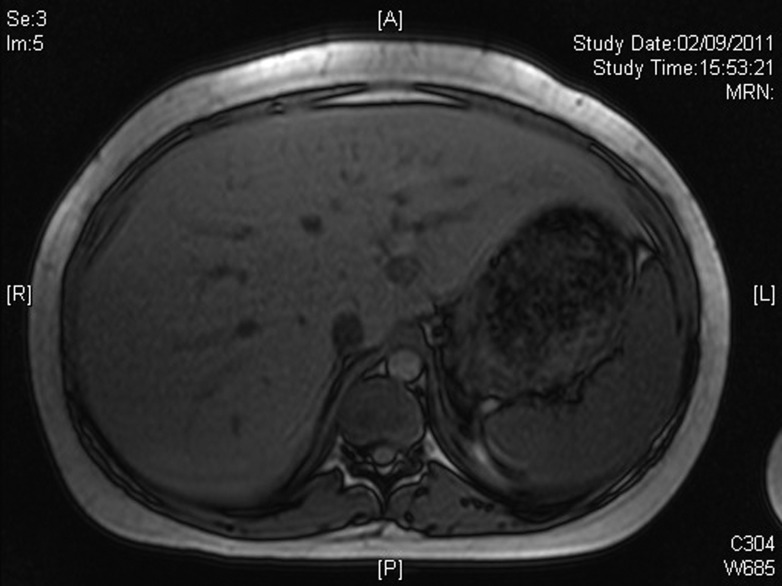

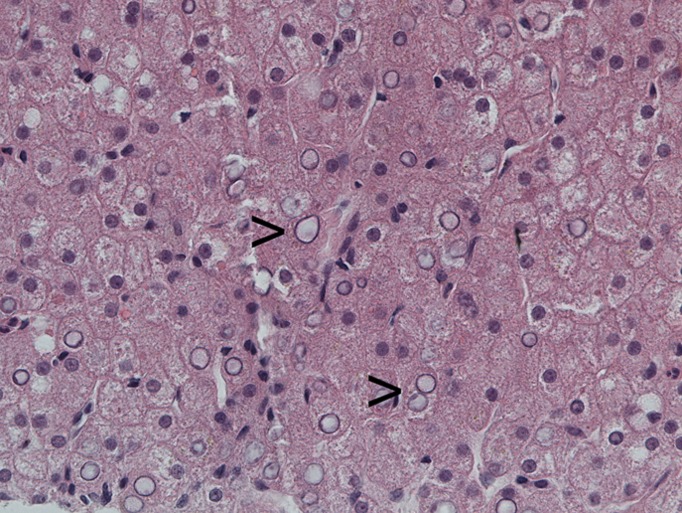

A 19-year-old type 1 diabetic female with poor glycemic control, complicated by recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) was admitted in August 2011 with symptoms of feeling generally unwell, abdominal pain, vomiting, and breathlessness. Her glycemic control had been suboptimal for several years (HbA1c [NGSP] 14.6%, [International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine] 136 mmol/mol in July 2010). She was treated for DKA and had tender hepatomegaly. Investigations revealed abnormal liver function tests including γ-glutamyl transferase 317 (normal range [NR] 1–42 units/L), alanine aminotransferase 199 (NR 1–41 units/L), alkaline phosphatase 139 (NR 30–130 units/L); serum lipid profile was adverse including total cholesterol (TC) 9.42 mmol/L (NR <5.2), triglyceride 9.96 (NR <1.71), HDL 1.65 (NR >1.42), TC/HDL 5.7 (NR <3.9). However, other causes of liver injury were excluded. Magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 1) also revealed enlarged smooth liver (27 cm) and no evidence of cirrhosis, fibrosis, fatty change, or other focal parenchymal lesion. Liver biopsy (Fig. 2) showed extensive glycogenation of the nuclei with no increase or evidence of parenchymal abnormality. Periodic acid Schiff stain for glycogen was positive in these hepatocytes. A diagnosis of glycogenic hepatopathy was made after clinicopathological correlation. She had five further episodes of DKA from October 2011 through January 2012. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII; insulin pump therapy) was considered as an option; she received further education and carbohydrate counting. She started CSII in early February 2012, and her insulin requirements came down enormously. Investigations on 3 May 2012 showed improvement in glycemic control, HbA1c 62 mmol/mol, 7.8% and lipid profile, TC 6.24 mmol/L, triglyceride 2.43 mmol/L, and normal liver transaminases. Abdominal ultrasound performed 10 weeks post–pump initiation showed complete resolution of hepatomegaly with normal liver echogenicity and size.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing marked hepatomegaly. A, anterior; L, left; P, posterior; R, right.

Figure 2.

Liver biopsy. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, high magnification showing marked nuclear glycogenization, seen as empty nuclei (arrowheads).

Glycogenic hepatopathy was first described by Mauriac, in 1930, in diabetic children as part of a syndrome that can occur without the syndromal features in adults with type 1 diabetes (2). The key feature is glycogen accumulation in the liver causing hepatomegaly and raised serum transaminases with wide fluctuations in both glucose and insulin levels. This glycogen production persists even after insulin levels have declined and leads to glycogen accumulation. Genetic links have also been described (2). An important differential diagnosis is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Persistent and relatively mild disturbance in liver function favors nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; transaminase flares are more compatible with glycogenic hepatopathy. The hallmark of this condition is its reversibility with improved glycemic control, unlike hepatic steatosis; glycogen overload is not known to progress to fibrosis, distinct from fatty liver disease (3). A final distinction can be made with a liver biopsy.

It is important to distinguish this entity because it has the potential for resolution after improved glycemic control (4). To our knowledge, this is the first case in literature where improved glycemic control after treatment with CSII resulted in complete resolution of glycogenic hepatopathy.

Acknowledgments

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

K.E.I. wrote the manuscript. C.H. and S.S. contributed to the figures. I.D. reviewed the manuscript. F.A., J.R., and F.K. contributed to the discussion. K.E.I. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank Elaine Kershaw, secretary in medical directorate, Lancashire Teaching Hospital, Chorley, U.K., for typing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Aljabri KS, Bokhari SA, Fageeh SM, Alharbi AM, Abaza MA. Glycogen hepatopathy in a 13-year-old male with type 1 diabetes. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31:424–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Brand M, Elving LD, Drenth JP, van Krieken JH. Glycogenic hepatopathy: a rare cause of elevated serum transaminases in diabetes mellitus. Neth J Med 2009;67:394–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saxena P, Turner I, McIndoe R. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic glycogen hepatopathy: a reversible condition. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudacko RM, Manoukian AV, Schneider SH, Fyfe B. Clinical resolution of glycogenic hepatopathy following improved glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications 2008;22:329–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]