Among 330 perinatally infected youths (mean age, 13.5 years), 28% reported sexual intercourse. Most reported unprotected sex and human immunodeficiency virus nondisclosure to first partners. Viral resistance to ≥1 antiretroviral medication was detected in 81% of sexually active youths with viral load ≥5000 copies/mL.

Keywords: perinatally HIV-infected, adolescents, viral drug resistance, sexual initiation, disclosure

Abstract

Background. Factors associated with initiation of sexual activity among perinatally human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected (PHIV+) youth, and the attendant potential for sexual transmission of antiretroviral (ARV) drug-resistant HIV, remain poorly understood.

Methods. We conducted cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of PHIV+ youth aged 10–18 years (mean, 13.5 years) enrolled in the US-based Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study between 2007 and 2009. Audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) were used to collect sexual behavior information.

Results. Twenty-eight percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 23%–33%) (92/330) of PHIV+ youth reported sexual intercourse (SI) (median initiation age, 14 years). Sixty-two percent (57/92) of sexually active youth reported unprotected SI. Among youth who did not report history of SI at baseline, ARV nonadherence was associated with sexual initiation during follow-up (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.87; 95% CI, 1.32–6.25). Youth living with a relative other than their biological mother had higher odds of engaging in unprotected SI than those living with a nonrelative. Thirty-three percent of youth disclosed their HIV status to their first sexual partner. Thirty-nine of 92 (42%) sexually active youth had HIV RNA ≥5000 copies/mL after sexual initiation. Viral drug resistance testing, available for 37 of these 39 youth, identified resistance to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in 62%, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in 57%, protease inhibitors in 38%, and all 3 ARV classes in 22%.

Conclusions. As PHIV+ youth become sexually active, many engage in behaviors that place their partners at risk for HIV infection, including infection with drug-resistant virus. Effective interventions to facilitate youth adherence, safe sex practices, and disclosure are urgently needed.

With life-extending antiretroviral (ARV) medications, children with perinatal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (PHIV+) in the United States are now reaching adolescence and young adulthood [1]. HIV infection adds further complexity to this stage of life which often includes initiation of sexual activity. During adolescence, poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is common [2, 3]. The substantial risk of viral drug resistance faced by PHIV+ youth, resulting from suboptimal adherence after a lifetime of ART, poses a threat to their own health and creates the risk of transmitting drug-resistant HIV to sexual partners. This risk is further heightened if PHIV+ youth fail to disclose their HIV infection to sexual partners and do not use condoms.

While several studies [4, 5] have examined factors influencing risky sexual behaviors of youth who acquired HIV infection through sexual behaviors and substance use, factors associated with sexual risk may be different for PHIV+ youth. The results of existing studies are mixed [6–13]. Small sample size, cross-sectional designs, and different age ranges and assessments may account for these differences and also limit the ability to define predictive factors. In a large cohort of PHIV+ youth in the United States with longitudinal assessment of sexual behavior, we estimated the prevalence and timing of initiation of vaginal and anal sexual intercourse (SI); examined HIV disease-related, behavioral, and psychosocial factors for associations with initiation of SI and with unprotected SI; and described the extent of HIV disclosure to sexual partners. To explore the potential for transmission of drug-resistant virus, we summarized the prevalence of ARV drug resistance among sexually active PHIV+ youth with viral load ≥5000 copies/mL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP) of the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) is a prospective study examining the impact of HIV infection and ART on PHIV+ children and adolescents. PHIV+ youth were enrolled beginning March 2007 at 15 sites in the United States including Puerto Rico. Eligibility criteria included perinatal HIV infection, age 7 to <16 years at enrollment, and engagement in medical care with available ART history. Accrual closed in October 2009, with follow-up visits initially every 6 months and then yearly.

Institutional review boards (IRBs) at participating sites and the Harvard School of Public Health approved the protocol. Parents or legal guardians (caregivers) provided written informed consent for minor youth and caregiver participation, and youth provided assent per local IRB guidelines or adult self-consent if aged ≥18 years. A Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained. Youth were not required to know their HIV status in order to participate until they reached 18 years of age.

Clinical exams, medical chart abstractions, and interviews took place at each visit. We administered an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) annually to participants ≥10 years of age, beginning with the 6-month visit, to collect information on sex and substance use behaviors. Caregivers were administered questionnaires regarding their caregiver–child relationship and their children's emotional and behavioral health.

Outcome

Sexual behavior was assessed with ACASI using the Adolescent Sexual Behavior assessment [14]. After initial screening questions, those who reported sexual activity answered more detailed questions on lifetime and recent (past 3 months) sexual activity, including type of contact (oral, vaginal, anal, genital touching), age at initiation, first partner type (boyfriend/girlfriend, casual, other), numbers of partners and sexual acts, same-sex behaviors, and condom use. We defined 3 primary outcomes: (1) prevalent SI, (2) initiation of SI, and (3) any SI without a condom (unprotected SI).

Covariates

Substance Use

Substance use was assessed with ACASI and included questions about lifetime and recent use (past 3 months) of cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, heroin, inhalants, and over-the-counter or prescription drugs used for purpose of intoxication. For analyses, substance use was defined as recent use of any substance.

HIV Disease–Related Characteristics

Information included Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical classification, CD4+ T-lymphocyte (CD4) count, HIV RNA plasma concentrations (viral load [VL]), youth's knowledge of their HIV status (as indicated by caregiver), and nonadherence to ARV medications. We defined nonadherence as at least 1 missed dose within the past 7 days, as reported by either caregivers or youth in private, separate interviews. This measure was shown to have a strong association with VL >400 copies/mL in this population [15].

Psychosocial Variables

At the entry visit, youth and caregivers were interviewed separately using the Behavior Assessment System for Children–Second Edition (BASC-2), which assesses participants’ emotional and behavioral health [16]. We included 2 primary summary scores: the parent-reported Behavioral Symptoms Index and the youth-reported Emotional Symptoms Index.

At the 6-month visit, caregivers were interviewed using the Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI) to assess caregiver-child relationship and parenting attitudes [17]. We considered 4 domain/content scales (Parent Support, Involvement, Communication, Limit Setting). The PCRI has an overall median consistency of 0.82 across subgroups and good test-retest reliability.

Sociodemographics

Demographic variables included race and ethnicity, age, sex, annual household income, caregiver education, caregiver relationship to youth, and Tanner sexual maturity stage.

Other Variables

Drug Resistance

The specific mutations conferring viral resistance to ARV medications (protease inhibitors [PIs], nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs], and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NRTIs]) were abstracted from medical charts. Stored plasma samples were tested for resistance mutations by consensus sequencing (Quest Diagnostics, Baltimore, Maryland) for those without documented resistance testing. The Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database (http://hivdb.stanford.edu/) was used to interpret all genotype results. “Intermediate-” or “high-level” resistance to a drug was classified as resistant, while “susceptible,” “potential low-level,” or “low-level” resistance was classified as susceptible. We assessed resistance to 8 PIs (atazanavir, darunavir, fosamprenavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir), 7 NRTIs (lamivudine, abacavir, zidovudine, stavudine, didanosine, emtricitabine, and tenofovir) and 3 NNRTIs (efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine).

HIV Disclosure

Questions on HIV disclosure to sexual partners were added to the ACASI in November 2009. To avoid inadvertent disclosure to youth unaware of their infection status, only youth who endorsed HIV infection from a list of chronic medical conditions responded to partner disclosure questions (knowledge of HIV status prior to first sexual act; whether youth disclosed their status to their first partner).

Statistical Analysis

The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Prevalence of SI

We estimated prevalence overall and by age, using data available through the most recent ACASI.

Initiation and Predictors of Onset of SI

This longitudinal analysis included participants who reported no history of SI at their first ACASI (“baseline”) and who completed at least 1 additional ACASI. The outcome was SI initiation since the baseline ACASI. Time to initiation was defined as the difference between age at the baseline ACASI and age at which SI was reported to have first occurred. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we examined the association between baseline covariates and SI initiation. Covariates were measured at or prior to the time of the baseline ACASI. Individuals who reported no SI as of their most recent ACASI were censored at this visit.

Correlates of Unprotected SI

This cross-sectional analysis included all participants reporting at least 1 episode of SI. Logistic regression models were used to identify factors independently associated with unprotected sex. The first report of SI was used, and covariates were measured at or prior to the time of the ACASI at which SI was first reported.

Model-building began with inclusion of all covariates associated with the outcome (P < .10) in unadjusted analyses. Covariates no longer associated with the outcome (P > .05) were removed 1 at a time unless they changed the effect estimate for other covariates by ≥15%. A missing indicator was used when >10% of data were missing for a covariate.

In addition to the above associations, we summarized viral drug resistance for participants reporting SI and with at least 1 VL ≥5000 copies/mL after sexual initiation as follows: the proportion of youth with resistance to ≥1 drug in at least 1 class (PI, NNRTI, NRTI), to all drugs in each class, and to multiple classes; and the proportion of youth with any resistance mutations reporting unprotected sex. We also summarized disclosure to first sexual partners for the subset of participants who responded to these new questions.

Data available as of January 2011 were included.

RESULTS

Of 377 PHIV+ youth, 330 (88%) completed ≥1 ACASI. Youth were eligible to complete up to 3 ACASIs, through the 2.5-year visit. For 47 youth missing all expected ACASIs, 29 (62%) were expected to have completed 1, 14 (30%) were expected to have completed 2, and 4 (8%) were expected to have completed 3. Those missing all ACASIs were younger than those completing ≥1 ACASI (12.6 vs 13.5 years, P < .01, using age at first expected ACASI); after adjusting for age, they were also more likely to be missing adherence information. The most common reasons for missed ACASIs were cognitive impairment (34%), caregiver refusal (26%), and insufficient time or scheduling difficulties (25%).

Approximately half the youth with completed ACASIs were female, and the majority were black, non-Hispanic (Table 1). The mean age at first ACASI was 13.5 years (range, 9.8–18.4). Just over one-third of youth were living with their biological mothers, and almost half had annual household incomes ≤$20 000. Most youth did not report recent substance use. The majority who did reported use of alcohol or marijuana (data not shown).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, 2007-2010, at Time of First ACASI Completion

| Variable | Males (n = 159) | Females (n = 171) | Total (N = 330) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group, y | |||

| 10–11 | 40 (25.1) | 47 (27.5) | 87 (26.4) |

| 12–13 | 48 (30.2) | 51 (29.8) | 99 (30.0) |

| 14–15 | 48 (30.2) | 52 (30.4) | 100 (30.3) |

| 16–18 | 23 (14.5) | 21 (12.3) | 44 (13.3) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 109 (68.5) | 125 (73.1) | 234 (70.9) |

| White/other | 41 (25.8) | 37 (21.6) | 78 (23.6) |

| Missing | 9 (5.7) | 9 (5.3) | 18 (5.5) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 44 (27.7) | 39 (22.9) | 83 (25.2) |

| Primary caregiver | |||

| Biological mother | 57 (35.8) | 64 (37.4) | 121 (36.7) |

| Other biological relative | 48 (30.2) | 59 (34.5) | 107 (32.4) |

| Nonrelative | 54 (34.0) | 48 (28.1) | 102 (30.9) |

| Household income | |||

| ≤$20 000 | 63 (39.6) | 77 (45.0) | 140 (42.4) |

| >$20 000 to < $40 000 | 50 (31.5) | 45 (26.3) | 95 (28.8) |

| ≥$40 000 | 38 (23.9) | 39 (22.8) | 77 (23.3) |

| Missing/unknown | 8 (5.0) | 10 (5.9) | 18 (5.5) |

| Recent substance use | 29 (18.2) | 26 (15.2) | 55 (16.7) |

| Viral load >400 copies/mL | 45 (28.3) | 57 (33.3) | 102 (30.9) |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | |||

| <350 | 12 (7.5) | 26 (15.2) | 38 (11.5) |

| 350–500 | 17 (10.7) | 23 (13.5) | 40 (12.1) |

| >500 | 130 (81.8) | 122 (71.3) | 252 (76.4) |

| CDC Class C | 35 (22.0) | 47 (27.5) | 82 (24.9) |

All data are presented as No. (%).

Abbreviations: ACASI, audio computer-assisted self-interview; CDC Class C, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category C AIDS-indicator clinical condition; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

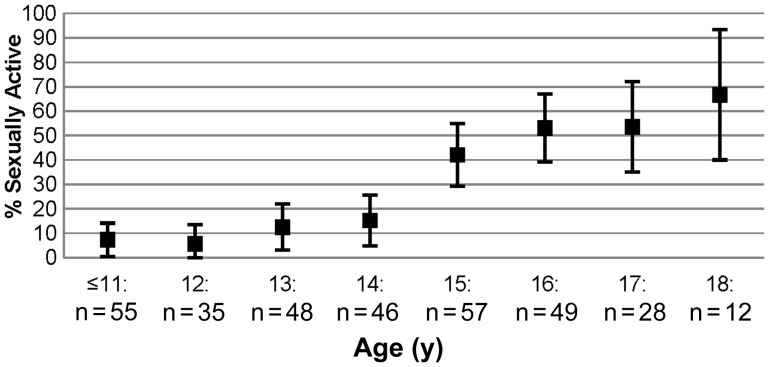

Figure 1 summarizes the proportion of sexually experienced youth, by age. Overall, 28% (95% confidence interval [CI], 23%–33%) reported SI at their baseline (n = 61) or a follow-up ACASI (n = 31). Thirty percent of males and 26% of females reported lifetime SI. The proportion of sexually experienced youth increased with age. SI was reported by 53% of 16-year-olds (95% CI, 39%–67%) and 67% of 18-year-olds (95% CI, 40%–93%). Among high-school-aged youth (14–18 years) 42% reported SI (95% CI, 35%–49%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of youth perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus who have had sexual intercourse, by age (n = 330).

Table 2 summarizes the sexual behaviors of sexually active youth by sex. Males reported a younger median age at first vaginal SI (13 vs 14 years, P = .007) or oral sex (13 vs 15 years, P = .02) and more anal intercourse partners (P = .04). There were no other differences by sex, including prevalence of unprotected SI (more than half of both males and females), having a same-sex partner (13% of males and 21% of females), and recent SI (64% overall).

Table 2.

Sexual Behaviors of Sexually Active Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, 2007–2010 (n = 92)

| Behavior | Males (n = 48) | Females (n = 44) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal intercourse | 43 (89.6) | 43 (97.7) | .11 |

| Any unprotected vaginal sex | 25 (58.1) | 27 (62.8) | .66 |

| Anal intercourse | 25 (52.1) | 17 (38.6) | .20 |

| Any unprotected anal sex | 15 (60.0) | 12 (70.6) | .48 |

| Oral sex | 40 (83.3) | 34 (77.3) | .46 |

| Recent sexual intercourse (past 3 mo) | 30 (62.5) | 29 (65.9) | .73 |

| Ever same-sex partner | 6 (12.5) | 9 (20.5) | .30 |

| First partner type | |||

| Girlfriend/boyfriend | 23 (53.5) | 30 (69.8) | .12 |

| Casual/other | 20 (46.5) | 13 (30.2) | |

| Age at first vaginal intercourse, median (IQR), range | 13 (12–14), 5–17 | 14 (14–15), 11–17 | .007 |

| Age at first anal intercourse, median (IQR), range | 14 (12–15), 8–16 | 14 (13–16), 6–18 | .14 |

| Age at first oral sex, median (IQR), range | 13 (12–15), 5–17 | 15 (14–15), 10–18 | .02 |

| Number of vaginal sex partners, median (IQR), range | 3 (2–5), 1–30 | 2 (1–4), 1–36 | .12 |

| Number of anal sex partners, median (IQR), range | 1 (1–3), 1–8 | 1 (1–1), 1–2 | .04 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range.

aP value for comparison of proportions between sexes is from χ2 test; P value for comparison of medians is from Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Predictors of Initiating Sexual Intercourse

Among the 269 youth reporting no history of SI at their baseline ACASI, 160 completed at least 1 follow-up ACASI by the time of these analyses; 31 (19%) of these 160 youth reported initiating SI during follow-up. There were no demographic or HIV disease differences between those with 1 or more follow-up ACASI vs none. Youth nonadherent to ARVs at baseline were significantly more likely than adherent youth to initiate SI during follow-up (hazard ratio [HR], 2.87; 95% CI, 1.32–6.25) (Table 3). Genital touching and older age at baseline were strongly associated with sexual initiation. No other variables were associated with initiating SI.

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Initiation of Vaginal or Anal Intercourse Among Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, 2007–2010 (n = 160)

| Univariable Models |

Multivariable Modela |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. (%) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD) | 13.3 (1.8) | 1.63 (1.31–2.03) | .001 | 1.55 (1.20–2.01) | .001 |

| Any baseline genital touching | 15 (9) | 9.67 (4.56–20.5) | .001 | 2.72 (1.01–7.31) | .05 |

| Missed ≥1 ARV dose in past 7 db | 42 (26) | 3.02 (1.42–6.42) | .004 | 2.87 (1.32–6.25) | .008 |

| Recent substance use at baseline | 16 (10) | 3.82 (1.76–8.31) | .001 | … | … |

| Knowledge of HIV status | 129 (81) | 7.13 (.97–52.3) | .05 | … | … |

| Tanner Stageb | |||||

| ≥4 | 68 (43) | 3.89 (1.79–8.47) | .001 | … | … |

| 1–3 | 91 (57) | ref | |||

| Household incomeb | |||||

| ≤$20 000 | 64 (42) | 3.77 (.85–16.7) | .08 | ||

| $21 000–$40 000 | 52 (35) | 5.42 (1.23–23.9) | .03 | … | … |

| >$40 000 | 34 (23) | ref | |||

| Any baseline oral sexc | 5 (3) | 4.17 (1.26–13.8) | .02 | … | |

Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; SD, standard deviation.

a All variables included in the multivariable model are those associated with the outcome at P < .05, or that confounded the effect of other covariates.

b Missing observations: missed >1 ARV dose past 7 days, n = 15; household income, n = 10; Tanner stage, n = 1.

c Oral sex not included in multivariable model because it was collinear with genital touching.

Factors Associated With Unprotected Sex

Among 92 youth reporting SI at their initial or follow-up ACASI, 57 (62%) reported having unprotected SI; 42 (46%) reported anal SI, of whom 27 (64%) reported unprotected anal SI (60% of males, 71% of females; P = .48). Four of 25 males (16%) who reported anal sex reported anal sex with a male partner. Three of these 4 males reported some unprotected anal sex. Youth living with a relative other than their biological mother had increased odds of unprotected sex compared to those living with a nonrelative, as did youth whose household income was ≤$20 000 (Table 4). No other variables were associated with unprotected SI.

Table 4.

Factors Associated With Unprotected Vaginal or Anal Intercourse Among Perinatally HIV-Infected Youth in the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study, 2007-2010 (n = 92)

| Univariable Models |

Multivariable Modela |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Household income ≤$20 000b | 44 (51) | 3.18 (1.31–7.75) | .01 | 2.84 (1.13–7.15) | .03 |

| Primary caregiver | |||||

| Biological mother | 43 (47) | 2.78 (.93–8.27) | .07 | 1.70 (.53–5.47) | .37 |

| Other biological relative | 28 (30) | 5.00 (1.47–17.0) | .01 | 4.00 (1.08–14.8) | .04 |

| Nonrelative | 21 (23) | ref | ref | ||

| Age at first sex, mean (SD)b | 13.6 (2.3) | .81 (.66–1.01) | .06 | … | … |

| CDC Class C | 21 (23) | 3.11 (1.03–9.41) | .04 | … | … |

Abbreviations: CDC Class C, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Category C AIDS-indicator clinical condition; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

a All variables included in the multivariable model are those associated with the outcome at P < .05, or that confounded the effect of other covariates.

b Missing observations: household income, n = 6; age at first sex, n = 3.

Antiretroviral Resistance

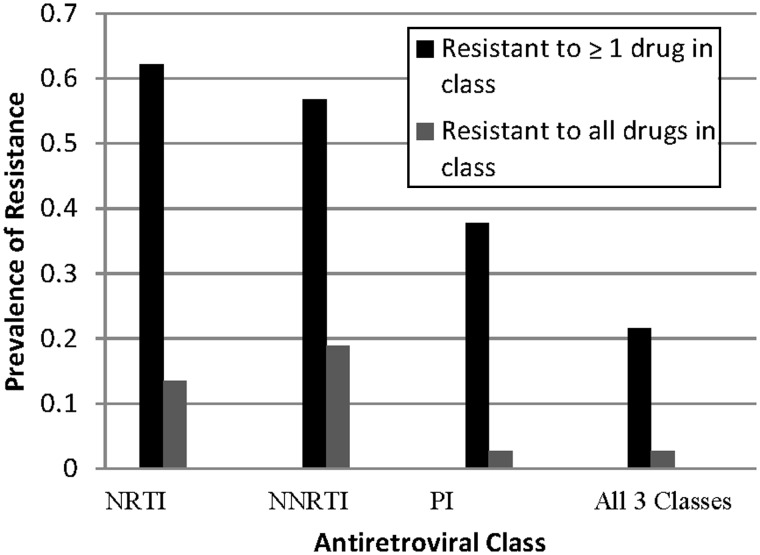

Thirty-nine of the 92 sexually active youth (42%) had at least 1 VL measurement of ≥5000 copies/mL after initiating SI, and viral drug resistance data were available for 37. Thirty of these 37 youth (81%) had mutations conferring resistance to drugs in 1 or more classes, most frequently to NRTIs (n = 23; 62%); 8 (22%) had resistance to 1 or more drugs in all 3 classes, and 1 youth had resistance to all drugs assessed in all 3 classes (Figure 2). The median number of drugs per class to which resistance was detected was 3 (range, 0–7) for NRTIs and 0 (range, 0–8) for PIs, respectively. Twenty-one youth (57%) were resistant to NNRTIs, including 7 (19%) with resistance to etravirine, which is generally used as part of salvage therapy for patients with resistance to other NNRTIs. Nineteen of the 30 youth (63%) with any resistance mutations reported unprotected sex.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of viral drug resistance among sexually active youth with ≥1 viral load measurement of ≥5000 copies/mL (n = 37). NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

Disclosure of HIV Status to Sexual Partners

Information about HIV disclosure to sexual partners was available for 67 (73%) of the 92 sexually active youth. Fifty-five (82%) youth reported knowing they were HIV-infected the first time they had SI; 33% of these 55 youth told their first partner about their HIV infection, including 4 who disclosed after having intercourse. Fifteen of the 18 youth who disclosed (83%) and 31 of the 37 youth who did not disclose (84%) had discussed condom use with their partner (P = .97). Condom use with the first partner was reported by 67% of those who discussed condom use with this partner, and by 22% of those who did not discuss condom use (P = .04).

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first prospective investigations of initiation of sexual intercourse among PHIV+ youth [7, 18] and the first study to describe ARV drug resistance in sexually active PHIV+ youth. Forty-two percent of 14- to 18-year-old youth reported SI, similar to the prevalence reported in 2 recent PHIV+ cohorts [7, 12] and to the overall prevalence for US high school youth, but somewhat lower than the experience for youth with similar demographic backgrounds [19]. Among sexually active youth, the proportion with recent SI was lower, and the number of lifetime sexual partners smaller, than recently described in a cohort of behaviorally HIV-infected youth [12].

Sexual intercourse, while a normal developmental milestone, presents special challenges for PHIV+ youth given the potential consequences of unprotected sex for themselves and their partners. The majority of sexually active youth in our study reported having had unprotected sex; moreover, a high proportion engaged in unprotected anal intercourse. Almost half had VL ≥5000 copies/mL at some point after initiating sex, increasing the risk of transmission to sexual partners [20]. Notably, more than three-quarters of these youth had drug-resistant virus, including a substantial portion with multiclass resistance. This resistance is permanent, limiting future treatment options both for PHIV+ youth and their partners if infected with resistant virus. HIV-infected individuals are also at heightened risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections [21], highlighting the need for clinicians to emphasize safe-sex behaviors during consultation with PHIV+ youth.

The co-occurrence of nonadherence and risky sexual behaviors has been previously described [22–26]. Among adults, it has been suggested that this association may be related to hopelessness [22] or other psychosocial issues [23]. Among youth, both nonadherence and sexual initiation may be expressions of independence or the desire to feel accepted by peers [27–29]. The desire for independence can be used in interventions that frame adherence and safe-sex practices as behaviors that protect not only one's own health, but that of one's sexual partners [30]. Knowledge that ART can dramatically reduce the likelihood of sexual transmission of HIV [31] may encourage youth to optimize their adherence. By emphasizing both adherence and condom use, interventions can give youth the critical knowledge needed to reduce HIV transmission to their partners.

Eighteen percent of sexually active youth did not know that they were HIV-infected before initiating SI, so they did not have the opportunity to disclose to sexual partners. Youth's knowledge of their HIV infection status prior to sexual initiation is critical [32]. However, among those who did know their status, most did not disclose it to their first partners. This nondisclosure, a finding previously observed [12], may be due to youth's normal fear of rejection and desire for intimacy [33, 34]. Yet it is notable that most youth did discuss condom use with their first partners, and this discussion was associated with higher odds of condom use. Condom use is essential and should be strongly encouraged; because consistent use can be difficult to achieve, HIV disclosure as well as condom use and adherence should be emphasized, so that sexual partners are empowered to make safe choices.

Our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional characterization of resistance for a subset of PHIV+ youth may not be representative of longitudinal drug-resistance patterns overall. We did not summarize resistance for all youth but only for those sexually active and with an elevated VL. However, the level of resistance we observed was highly consistent with that in several European cohorts of perinatally infected youth [35–38].

Those missing all ACASIs were also more likely to be missing adherence information. This may have biased the association between nonadherence and initiation of SI; however, this would require that youth with missing data were either (1) nonadherent and without SI initiation, or (2) adherent and with SI initiation. Along with the small number of youth (n = 18; 10% of those eligible) with missing data who would have been eligible for the initiation analysis (those missing ≥2 ACASI), these scenarios suggest that any bias is minimal.

There were 8 reports of sexual initiation at a very young age that we did not attempt to verify through medical records review owing to the confidential nature of our sexual behavior assessments. We therefore cannot determine whether these reports are due to poor recall or exaggeration, or are cases of abuse. However, 4 of these youth completed a subsequent ACASI, and their reported age at initiation was consistent (within 1 year). We did not collect information on coerced sexual experiences and other important predictors of risky sexual behavior. We were unable to focus on factors associated with more recent sexual activity since only 64% of this young cohort reported recent SI. As this cohort ages through adolescence and young adulthood, it will be important to explore additional associations with sexual initiation as well as changes in sexual behaviors over time.

Perinatally HIV-infected youth are becoming sexually active, with some engaging in behaviors that may adversely affect their health and that of their sexual partners. Interventions that enhance ARV medication adherence, consistent condom use, and HIV disclosure to sexual partners are essential as these youth prepare for independent living and transition to adulthood [39].

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the children and families for their participation in PHACS, and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS.

The following institutions, clinical site investigators, and staff participated in conducting the PHACS Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP) in 2010, in alphabetical order: Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Mary Paul, Norma Cooper, Lynette Harris; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Mahboobullah Baig, Anna Cintron; Children's Diagnostic and Treatment Center: Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro, Doyle Patton, Deyana Leon; Children's Hospital, Boston: Sandra Burchett, Nancy Karthas, Betsy Kammerer; Children's Memorial Hospital: Ram Yogev, Margaret Ann Sanders, Kathleen Malee, Scott Hunter; Jacobi Medical Center: Andrew Wiznia, Marlene Burey, Molly Nozyce; St Christopher's Hospital for Children: Janet Chen, Latreca Ivey, Maria Garcia Bulkley, Mitzie Grant; St Jude Children's Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison, Megan Wilkins; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Heida Rios, Vivian Olivera; Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Margarita Silio, Medea Jones, Patricia Sirois; University of California, San Diego: Stephen Spector, Kim Norris, Sharon Nichols; University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center: Elizabeth McFarland, Emily Barr, Robin McEvoy; University of Maryland, Baltimore: Douglas Watson, Nicole Messenger, Rose Belanger; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica, Susan Adubato; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Patricia Bryan, Elizabeth Willen.

Author contributions. K. T. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. K. T., A.-B. M., C. M., G. R. S., and R. B. V. D. were responsible for the study concept and design. K. M., R. S., and M. P. were responsible for acquisition of data. All authors participated in analysis and interpretation of data and for critical revision of the manuscript. K. T. was responsible for drafting of the manuscript and for statistical analysis. G. R. S. and R. B. V. D. acted as study supervisors and obtained funding for the study.

Disclaimer. The funding organizations were involved in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Financial support. The Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) with co-funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Office of AIDS Research (OAR), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NICDC), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (HD052102, 3 U01 HD052102-05S1, 3 U01 HD052102-06S3) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (HD052104, 3U01HD052104-06S1). Data management services were provided by Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation, and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Brady MT, Oleske JM, Williams PL, et al. Declines in mortality rates and changes in causes of death in HIV-1-infected children during the HAART era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:86–94. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b9869f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams PL, Storm D, Montepiedra G, et al. for the PACTG 219C Team. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral medications in children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1766–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steele RG, Grauer D. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: review of the literature and recommendations for research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2003;6:17–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022261905640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotheram-Borus M, Lee M, Zhou S, et al. Variation in health and risk behavior among youth living with HIV. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2001;13:42–54. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.1.42.18923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sturdevant M, Belzer M, Weissman G, et al. the Adolescent Medicine HIV/AIDS Research Network. The relationship of unsafe sexual behavior and the characteristics of sexual partners of HIV infected and HIV uninfected adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3S):64–71. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauermeister JA, Elkington K, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Sexual behavior and perceived peer norms: comparing perinatally HIV-infected and HIV-affected youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38:1110–22. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9315-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauermeister JA, Elkington K, Robbins R, Kang E, Mellins CA. A prospective study of the onset of sexual behavior and sexual risk in youth perinatally infected with HIV. J Sex Res. 2012;49:413–22. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.598248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellins C, Elkington K, Bauermeister J, et al. Sexual and drug use behavior in perinatally HIV-infected youth: mental health and family influences. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:810–9. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a81346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frederick T, Thomas P, Mascola L, Hsu HW, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-infected adolescents: a descriptive study of older children in New York City, Los Angeles County, Massachusetts and Washington, DC. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:551–5. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brogly S, Watts H, Ylitalo N, et al. Reproductive health of adolescent girls perinatally-infected with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1047–52. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezeanolue E, Wodi A, Patel R, Dieudonne A, Oleske J. Sexual behaviors and procreational intentions of adolescents and young adults with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection: experience of an urban tertiary center. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig L, Pals S, Chandwani S, et al. Sexual transmission risk behavior of adolescents with HIV acquired perinatally or through risky behaviors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:380–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f0ccb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setse R, Siberry G, Gravitt P, et al. for the Legacy Consortium. Correlates of sexual activity and sexually transmitted infections among human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth in the LEGACY cohort, United States, 2006. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:967–73. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182326779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolezal C, Marhefka SL, Santamaria EK, Leu CS, Brackis-Cott E, Mellins CA. A comparison of audio computer-assisted self-interviews to face-to-face interviews of sexual behavior among perinatally HIV-exposed youth. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:401–10. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9769-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Usitalo A, Leister E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. for the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS) Relationship between viral load and behavioral measures of medication adherence among youth with HIV. Abstract presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting, 1–4 May 2010, Vancouver, BC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior assessment system for children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerard AB. Parent-child relationship inventory manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiener L, Battles H, Wood LV. A longitudinal study of adolescents with perinatally or transfusion acquired HIV infection: sexual knowledge, risk reduction self-efficacy and sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:471–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9162-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. Surveillance summaries. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1–142. (No. SS-5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes J, Baeten J, Lingappa J, et al. The Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1–serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:358–65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClelland R, Lavreys L, Katingima C, et al. Contribution of HIV-1 infection to acquisition of sexually transmitted disease: a 10-year prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:333–8. doi: 10.1086/427262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman S, Rompa D. HIV treatment adherence and unprotected sex practices in people receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:59–61. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson T, Barron Y, Cohn M, et al. for the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its association with sexual behavior in a national sample of women with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:529–34. doi: 10.1086/338397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remien R, Exner T, Morin S, et al. for the NIMH Healthy Living Project Team. Medication adherence and sexual risk behavior among HIV-infected adults: implications for transmission of resistant virus. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:663–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flaks T, Burman W, Gourley P, Rietmeijer C, Cohn D. HIV transmission risk behavior and its relation to antiretroviral treatment adherence. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:399–404. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marhefka SL, Elkington K, Dolezal C, Mellins CA. Transmission risk behavior among youth living with perinatally acquired HIV: are nonadherent youth more likely to engage in sexual risk behavior? J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(suppl 1):S29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simoni J, Montgomery A, Marin E, New M, Demas P, Rana S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for pediatric HIV infection: a qualitative systematic review with recommendations for research and clinical management. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1371–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conway S. Transition from paediatric to adult-oriented care for patients with cystic fibrosis. Disabil Rehabil. 1998;20:209–16. doi: 10.3109/09638289809166731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taddeo D, Egedy M, Frappier JY. Adherence to treatment in adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:19–24. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotheram-Borus M, Lee M, Murphy D, et al. for the Teens Linked to Care Consortium. Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youths living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:400–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen M, Chen Y, McCauley M, et al. for the HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Disclosure of illness status to children and adolescents with HIV infection. Pediatrics. 1999;103:164–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiener L, Battles H. Untangling the web: a close look a diagnosis disclosure among HIV infected adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:307–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaud P, Suris J, Thomas P, Kahlert C, Rudin C, Cheseaux J. To say or not to say: a qualitative study on the disclosure of their condition by human immunodeficiency virus-positive adolescents. J Adolesc Health, 2009;44:356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaugerre C, Warszawski J, Chaix ML, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with antiretroviral resistance in HIV-1-infected children. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1261–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chakraborty R, Smith C, Dunn D, et al. for the Collaborative HIV Paediatric Study (CHIPS) and UK Collaborative Group on HIV Drug Resistance. HIV-1 drug resistance in HIV-1-infected children in the United Kingdom from 1998 to 2004. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:457–9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181646d6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Mulder M, Yebra G, Martin L, et al. for the Madrid cohort of HIV-infected children. Drug resistance prevalence and HIV-1 variant characterization in the naive and pretreated HIV-1-infected paediatric population in Madrid, Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2362–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Navas A, de Mulder M, Gonzales-Granados I, et al. for the Madrid cohort of HIV-infected children. High drug resistance prevalence among vertically HIV-infected patients transferred from paediatric care to adult units in Spain. Abstract presented at the Third International Workshop on HIV Pediatrics. 15–16 July 2011, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Battles H, Wiener L. From adolescence through young adulthood: psychosocial adjustment associated with long-term survival of HIV. J Adol Health. 2002;30:161–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]