Abstract

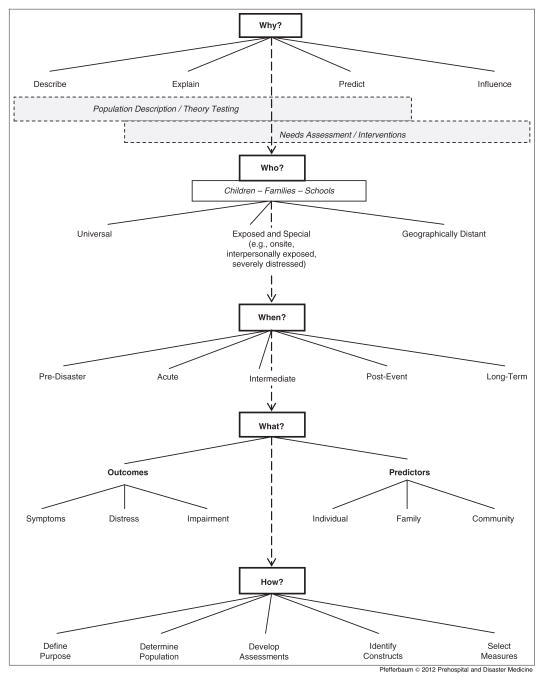

Clinical work and research relative to child mental health during and following disaster are especially challenging due to the complex child maturational processes and family and social contexts of children’s lives. The effects of disasters and terrorist events on children and adolescents necessitate diligent and responsible preparation and implementation of research endeavors. Disasters present numerous practical and methodological barriers that may influence the selection of participants, timing of assessments, and constructs being investigated. This article describes an efficient approach to guide both novice and experienced researchers as they prepare to conduct disaster research involving children. The approach is based on five fundamental research questions: “Why?, Who?, When?, What?, and How?” Addressing each of the “four Ws” will assist researchers in determining “How” to construct and implement a study from start to finish. A simple diagram of the five questions guides the reader through the components involved in studying children’s reactions to disasters. The use of this approach is illustrated with examples from disaster mental health studies in children, thus simultaneously providing a review of the literature.

Keywords: assessment, child trauma research, conducting research, disaster, disaster mental health, investigation, measurement, posttraumatic stress, research, research assessment, research variables, study design, terrorism, trauma

Introduction

Research on the mental health of children during and following a disaster is especially challenging due to the complex child maturational processes and family and social contexts of children’s lives. Research and clinical work with children and adolescents requires systematic attention to developmentally appropriate and relevant issues, as well as recognition of the vulnerabilities associated with childhood. Over time, disaster mental health research has attracted local investigators seeking to address issues that arise as part of clinical efforts or to expand knowledge about novel issues. Individuals representing a wide range of professional backgrounds may become involved in disaster work because of serendipitous circumstances requiring an immediate response to a community’s need for information and services. Others, who have developed expertise through prior work, constitute a cadre of seasoned disaster researchers who respond to calls for help.

Whether the study rationale involves descriptive (eg, portraying children’s disaster reactions) or informative (eg, guiding interventions) goals, researchers and clinicians should benefit from a systematic framework for approaching disaster mental health research with children and families. This article provides such a framework, and an overview of the mental health literature on children in the context of disasters and terrorist events.

Setting the Stage

Information gathering in a community grappling with the devastating effects of mass trauma is challenging due to four issues: (1) disruption and chaos; (2) damage to the infrastructure; (3) depletion of resources; and (4) limited access to potential participants—all of which may influence the feasibility of initiating a study, selection of participants, timing of assessments, and constructs chosen for investigation. Disasters present numerous practical and methodological barriers, rendering the task of conducting rigorous empirical investigations difficult. Additionally, researchers who seek to understand the reactions of children and adolescents may confront difficulties in accessing survivors who are willing and able to participate.1,2 As a result of these impediments, researchers historically have conducted studies based more on accessibility than on theory development.2

Framework for Research on Mental Health of Children

An efficient approach is presented to guide both novice and experienced researchers as they prepare to conduct disaster research. This method is derived from the foundational framework proposed by North and Norris,3 who identified specific questions researchers should consider when conducting disaster research studies. Five fundamental research questions guide the strategy: “Why?, Who?, When?, What?, and How?”

Why?

Disaster mental health assessment studies demonstrate the nature, severity, and extent of the effects disasters have on mental health and behavior,3 and assist in the development of interventions that promote recovery in groups of children who experienced various types and degrees of exposure to trauma, loss, and adversity. Spanning the entire life cycle of disaster, assessment is important in monitoring recovery, the effects of post-event circumstances, and the effectiveness of services and interventions.4 Measurements focus on variables such as exposure, subjective reactions, loss of significant others, property destruction, and post-event adversities that increase the risks for severe and persistent distress, behavioral and developmental problems, and functional difficulties. Results can aid clinical endeavors through the creation and implementation of preparedness activities and services and interventions from the acute and early post-event period through long-term recovery.

Providers and researchers in the disaster and post-disaster environment focus attention in the midst of sometimes frenetic conditions and activity, which may be true especially for those with dual responsibilities in providing clinical services and conducting research. Historically, often these roles have been best served by combining activities through data collection in the form of screening, needs assessment, clinical evaluation, treatment outcomes and program evaluation. Thus, despite the difficult environment, child disaster mental health assessment research has flourished over the past several decades, providing a base of knowledge about the deleterious effects of disasters and terrorist events on children.

To date, most disaster studies have focused on enhancing our understanding of the link between disaster-related variables (eg, exposure) and psychiatric symptomatology. As a result, the effects of disasters and terrorist events on children’s behavior and mental health have been well established through studies describing reactions without providing much in the way of explanation or prediction. More recently, assessment studies have sought to identify factors predictive of disaster outcomes or to demonstrate characteristics of effective interventions.

Investigations may be designed to elucidate the nature and course of psychopathology, through the use of comprehensive assessments, or they may be based on well-defined research questions that clarify existing knowledge and promote in-depth appreciation of disaster-related phenomena through focused assessments. As disaster research extends beyond the existing, widely-held knowledge of the impact of disasters on children, results contribute to theory building and to the development of effective services and interventions.

Hypothesis-generating research allows for the exploration of novel issues, such as the impact of the sociopolitical climate in which a disaster occurs. More work is needed to: (a) discover and test theoretical concepts; (b) explore issues related to the biology of stress reactions in children; (c) develop more comprehensive knowledge of the relationships among variables not yet substantiated (eg, whether prior trauma increases disaster vulnerability); and (d) clarify the role of family and other community and societal influences in children’s disaster reactions and recovery.

Within the area of disaster mental health assessment, some findings have contributed additional knowledge regarding: (1) a diversity of outcomes including posttraumatic stress, depression, other morbidities;5–7 and traumatic grief;8 and (2) predictors including the role of family factors9–12 and coping.13–18 Additionally, a recent trend in research on positive outcomes following disaster, including resilience and posttraumatic growth,19,20 represents a new and viable focus for study and theory development.

Who?

The “Who” of a disaster assessment study may be most straightforwardly defined by geographic distance from the impact site, with samples chosen based on physical proximity or by their residence within the community affected by the disaster or terrorist event. The nature of the incident and its unique characteristics influence the sample selected. Ideally, the selection of participants emerges from a priori theoretical considerations; often, however, it evolves from the practicality of the study and access to a sample.

Child and Adolescent Samples

Disaster research with children and adolescents is particularly challenging given the developmental and social factors that influence children’s reactions and recoveries, as well as the consent process and study methodology.2 In particular, very young children have been under-studied, though recent research has addressed preschool children.21–23 Identifying the age group(s) under investigation advances both theoretical and methodological purposes.

Accessing Participants

Researchers face difficulties accessing survivors who are willing and able to participate.1,2 In fact, the problem of access is likely to influence the selection of a research sample. Furthermore, adult observations are needed for young children who lack the conceptual and verbal skills to participate meaningfully, and adding further complexities to the recruitment process, children require parental consent for participation. Fortunately, children can be accessed through various means and locations, as delineated by Norris, who identified five sampling approaches to disaster research: convenience, purposive, clinical, random, and census approaches.24

Representative and random samples of children have been rare in disaster studies. In fact, Norris found that purposive sampling was used much more often in child disaster studies than in those with adults, and that children often were accessed through their schools.24 Convenience sampling also has been utilized to access large groups of children in a school setting, and has been best applied following a novel event (eg, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001) when no other sampling approach has been possible. Often, schools have been used as the point of selection for assessing large samples of children exposed to disaster, primarily because the school either has been the site of an incident (eg, school sniper attack,25 hostage-taking incident26,27) or has been located in the general area struck by a disaster16,28–30 or human-caused incidents.31

Accessing children through public school systems may supply researchers with children residing in the vicinity of a particular incident, but it does not provide access to children younger than school-age, children attending private schools, or those who are home-schooled. In addition, researchers may sacrifice some degree of representativeness when accessing samples of children through a school, because these children form a “cluster,” meaning that they would be similar to each other because of the common school setting. This concern may be minimized by accessing children from multiple schools in diverse neighborhoods throughout the community.

Accessing children in schools and other locations is complicated further by logistical, procedural, bureaucratic, ethical, funding, and other barriers.2,32 Lindy and colleagues described a protective shield that envelops severely traumatized individuals making it difficult to reach survivors, even to deliver services.33 Conducting research with affected children can be even more problematic, as both survivors and providers may be suspicious of research efforts.34 To address some of the obstacles, Steinberg and colleagues recommended that researchers offer training and resources for school personnel, ongoing surveillance, and opportunities for collaboration.35

Selecting Participants

Defining exposure and delineating groups of children based on their exposure is important in identifying disaster and terrorism survivors for potential participation in research. Some researchers focus on children with intense exposure who are likely to experience the greatest adverse effects,22,36 whereas others designate a broader participant base and study a general population or community sample of children with various levels of exposure, loss, and distress.7,14,37 Special populations, including directly-exposed children, may be the focus of study (see discussion below). Some researchers may choose to assess children whose parents or other family members were directly exposed or died as a result of the event.8 Importantly, research has demonstrated the importance of exposure factors other than direct physical experience such as the perception of life threat,38 experiences with “high-intensity” disaster events,22 and/or relationship with victims.37–40

The use of multiple informants as collateral sources of information, such as parents, teachers, and other professionals, allows for the most comprehensive appraisal of children’s reactions and functioning. While more difficult to access, siblings and other family members, classmates, and friends may provide unique perspectives of a child’s situation.2,41 While practical difficulties in accessing children and those who can provide information about them typically drive decisions about who should serve as respondents, whenever possible, parental reports should accompany those of their children.42 Collecting data directly from children and from their parents can identify important distinctions in the perceptions of children and their parents.10,43,44 For example, parents of children in the World Trade Center during the 1993 bombing reported a decrease in their children’s posttraumatic stress and incident-related fears at nine months following the exposure, but their children reported no decrease.10 Researchers should consider obtaining parental ratings whenever possible, recognizing that parents are better at reporting externalizing symptoms, while children may provide more accurate information regarding internalizing symptoms.45

When?

The specific timing of research assessments depends on the purpose (the “Why”) of the study, and must recognize temporal considerations within the disaster timeline and determine the optimal time to conduct an investigation that reflects the “Why, Who, and What.” The period for collecting data on children’s disaster reactions extends from the time before a disaster-producing event strikes to the weeks, months, and years that follow. A diverse terminology for time periods exists, with no established consensus. According to North and Norris, the first two to six months following the onset of a disaster constitute the “acute period” with the “intermediate” period occurring 12 to 18 months post event, and the “long-term” phase occurring two to three years after the precipitating event.3

Assessments must be conducted early enough in the aftermath of an event to avoid recall bias,46 yet not so soon that it mistakes the ubiquitous early and transient distress for psychopathology. Studies examining children relatively soon after the onset of disasters predominate to the extent that long-term effects have been under-studied.47 Unfortunately, existing research has relied primarily on one-time assessments rather than longitudinal approaches.47 A recent longitudinal study by McLaughlin and colleagues provided data from children and adolescents involved in Hurricane Katrina during a three-wave survey, spanning the time period from five to seven months, seven to 10 months, and 15 to 19 months post hurricane.48

Determining When to Conduct a Study

Pre-Disaster Assessment

Because of the unpredictability of disasters, prospective studies have been rare. Two methods have been applied for collecting pre-event data. First, as a result of ongoing studies, researchers may have access to pre-event data that provide a baseline for a preexisting sample.49,50 An alternative method involves the use of archival data from other sources on representative samples (eg, population data/rates) for comparison with data collected from a post-event sample.51 To explain or predict the true impact of a disaster on children, a baseline assessment of their functioning must be established. Therefore, while it is not necessarily practical, researchers are urged to explore avenues for utilizing existing data from ongoing studies or archival databases, or, if possible, to collect pre-event data on children at risk.

Longitudinal and Long-Term Assessment

While researchers have long recognized the benefits of a longitudinal approach, few studies of children have used longitudinal design. Rarely, studies entail long-term assessments beyond six months post event.47 A few researchers have documented the course of symptomatology through repeated evaluations of children, with results underscoring the impact of initial distress on the persistence of symptoms over time.14,30,52,53 Long-term studies that have assessed children years after exposure have elucidated factors related to disaster adjustment extending into decades post disaster.36,54–57 Using both self- and collateral reports, a series of Hurricane Katrina studies indicate that while improved from baseline, children exposed to the event continued to experience disaster-related distress from five to 27 months post hurricane.48,53

What?

The number of constructs relevant to assessment of disaster reactions is virtually limitless; thus, the broadest and most complex question is likely related to “what” child disaster researchers decide to include in their investigations. Traditionally, research has focused on documenting the prevalence and severity of children’s reactions to trauma, with primarily clinical applications. In more recent years, new questions have emerged, enhancing our knowledge of a variety of important factors that influence differences in the nature, course, and severity of children’s disaster reactions. A brief overview of the child disaster literature provides a record of the variables investigated as disaster outcomes, and the constructs identified as predictors or correlates in the child disaster literature.

Determining What Outcomes to Study

In terms of outcomes, specific psychological problems and non-specific distress commonly are used as indicators of the severity of disaster reactions.58 The extent to which children are affected depends on numerous factors, and an accurate evaluation is influenced by study design, sample, measurement tools, and importantly, the outcomes examined.

Symptoms and Diagnoses

Common outcomes examined in the child disaster literature include the presence or absence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and/or symptoms, depressive and anxiety disorders, behavioral disturbances, grief, and functional impairmen.38,59 Norris and colleagues identified PTSD and posttraumatic stress symptoms as the most commonly assessed mental health outcome for child and adult disaster survivors;58 few child studies involve comprehensive evaluations for the presence of PTSD.38

Balaban identified several factors to consider in assessing children’s mental health following disasters, highlighting the importance of moving beyond traditional evaluations for the presence of PTSD to include symptoms of multiple disorders and functioning.60 Other measures assess distress, anxiety, depression, grief, somatic complaints, anger, behavioral problems, substance use, academic performance, impairment, and coping.

Degree of Distress and/or Impairment

Studies typically have been used to assess outcomes by classifying samples according to the frequency or severity of symptoms or degree of reaction (eg, in terms of distress and/or impairment). Distress and impairment indicate the extent to which a child’s functioning has been disrupted, and are necessary for establishing a diagnosis. Dimensional symptom classifications (eg, mild, moderate, severe), other continuous variables (eg, number and frequency of PTSD symptoms), and discrete categories (eg, presence or absence of a mental disorder) have been used.

Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth

Disaster outcomes and the factors influencing them commonly have been cast in light of pathology, with relatively little attention to children who overcome significant trauma, or perhaps even thrive in the face of disasters. A growing body of literature contributes to our knowledge of positive outcomes of resilience and growth.20,61 Among disaster survivors, resilience describes restoration of functioning, despite the manifestation of some transient symptoms.62 Additionally, the concept of “posttraumatic growth” has emerged to explain positive changes following trauma (eg, greater appreciation for life, increased sense of personal strength), including personal, interpersonal (eg, improved relationships), and/or spiritual growth.20

Determining What Predictors to Study

Exposure

As indicated, exposure may be a predictor or correlate of disaster outcomes. Exposure has been measured in terms of a host of variables including physical proximity, perceived life threat, interpersonal relationships with victims, personal loss, life disruption, and/or contact with media coverage. More recent concerns, such as those associated with terrorist attacks, have focused on public health issues like the potential effects of television coverage on children with various forms and levels of exposure.37,63–69

Age/Development

While a child’s developmental stage will influence the expression of his/her disaster reactions, studies to date have not provided definitive evidence about the relative effects of disasters across age.58,70 The commonly-used cross-sectional designs that include children and adolescents of multiple ages have demonstrated trends particular to a specific group, but typically have obscured any age or developmental differences. Longitudinal designs and methods that transcend traditional linear correlation analysis may be needed to determine any true effects by comparing both intra- and inter-individual changes over time.

Gender

Studies also have produced mixed results with respect to gender differences in children’s disaster reactions. When identified as a correlate or predictor variable in disaster studies, female gender generally has been considered a risk factor for negative outcomes in terms of the development of PTSD or posttraumatic stress reactions,17,55,71–73 internalizing (versus externalizing) reactions,7 and emotional (versus behavioral) symptoms.71,72 Girls also appear to rely more on emotion-focused (versus problem-focused) coping than do boys.17,18 Gender is an important sociodemographic variable to consider in light of these outcomes; however, La Greca and Silverman and Norris and colleagues have questioned the legitimacy of the influence of gender, noting that results may have limited explanatory potential.58,70

Race/Culture

Some dated studies of young survivors have found disaster effects to be relatively equivalent across racial groups,17,73 a finding that is in contrast with adult studies that have revealed more disaster-related difficulties in individuals of minority group status compared with majority-group counterparts.58 Although minority racial status may exist as a risk factor for child disaster survivors,70 the relationship may be better explained by underlying causes, such as socioeconomic disparity,14 repeated exposure to trauma,38 social discrimination, and/or lack of extrafamilial support.73

Disposition and Pre-Existing Conditions

Disposition and preexisting conditions may be robust predictors of disaster reactions, but they remain under-studied. Similar to the “trait” versus “state” distinction used to describe certain symptoms of psychopathology, in addition to symptom presentations, disposition and temperament have emerged as potential correlates of disaster reactions. Trait anxiety71 and a general predisposition to perceive situations as threatening appear to be important factors contributing to children’s disaster-related distress.74 Furthermore, some evidence exists to support the risk posed by preexisting psychiatric conditions,75 anxiety,49,50,73 negative affect and depression,49,73 and academic and attention difficulties.38

Prior Trauma

Prior exposure to trauma may be a risk factor for the development of disaster-related symptoms.7,76 However, the classification of “prior trauma” varies, and at least one study has demonstrated contradictory findings.23 Thus, additional study is needed on this issue.

Parental Reactions and Family Issues

Though not usually examined in post-disaster assessments of children, parental stress is among the most robust predictors of children’s post-disaster adjustment.58 For example, Green and colleagues found a relationship between parental symptom severity and children’s PTSD symptoms following the Buffalo Creek dam collapse,77 and that the influence of parental disaster reactions on children’s symptomatology decreased as the children aged.78,79 The relationships between children’s and parents’ trauma reactions may be modulated by various parental factors that also influence children’s responses. For example, subsequent changes in parenting as well as enduring maternal distress have predicted children’s persisting distress, even more than children’s direct exposure to an Australian bushfire.52 In a study of adolescents and their parents geographically distant from the September 11 terrorist attacks, Gil-Rivas and colleagues found that greater adolescent-parent conflict was associated with adolescents’ distress, trauma symptoms, and functional impairment.9

Certain families may be at risk for maladjustment post disaster. Family cohesion (the flexibility of emotional bonds among family members) and adaptability (the capacity to adjust the power structure, roles, and norms within the family) have been examined in the context of adverse events.80 Child adjustment problems were associated with both too much and too little cohesion during Scud missile attacks in the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf War, suggesting that both disengaged families (which fail to help the child process the experience) and enmeshed families (which transmit unmodified negative emotions from one family member to another) may put children at risk.80,81 Other family characteristics or patterns of response have been linked to children’s disaster reactions, including irritable, depressed, and over-protective families,11,77 and families with parental stress and conflict.82

Secondary Adversities

An important factor that often has been overlooked in studies of child disaster survivors is the presence of stressful life events (particularly those involving loss and/or harm) that occur during and following the disaster. These secondary adversities may exacerbate the effects of the initial trauma and obstruct the recovery process. For example, among adolescents exposed to Hurricane Andrew, negative events that occurred after the storm were associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms, even after accounting for loss, prior trauma, fear, and decreased sense of safety.83 Unexpectedly high rates of PTSD among preschool children displaced by Hurricane Katrina raised questions about the potential effects of evacuation, sheltering experiences, or returning to view a damaged home.23

Determining What Measures to Utilize

The number of variables for inclusion in disaster mental health assessments is essentially infinite, making it impossible to incorporate all important predictors and outcomes into a single study. Practical concerns also dictate the extent to which researchers can conduct comprehensive evaluations of children’s temperaments, preexisting symptoms, trauma histories, functional status, parental factors, and post-disaster adversities, among other issues. Clearly, selected measures will reflect the previously determined Why, Who, and What of the study. Following their extensive review, Norris and colleagues contended that future studies need not re-establish the fact that disasters are psychologically consequential.84 Thus, researchers are urged to carefully choose instruments and measurement techniques that add to existing knowledge through in-depth evaluations or that examine new areas of interest.

Comprehensive assessments inform us about the seriousness of disaster-related psychopathology, and can be used to track its course through the use of longitudinal research. In-depth measures, such as diagnostic interviews, would be appropriate for determining the clinical relevance of outcomes or the influence of risk and protective factors. Focused assessments derived from well-defined research questions that clarify existing knowledge and allow in-depth appreciation of disaster-related phenomena may contribute to enhanced understanding of emerging issues such as posttraumatic growth.

The challenge of disaster mental health research involves establishing procedures for rapid access to affected populations for early data collection without compromising the integrity of sampling and quality of measurement. Screening tools may assist with identifying children in need of services or determining the effectiveness of interventions, but they have become somewhat obsolete for the purpose of identifying key predictors, requiring researchers to employ more thorough assessments and those that zero-in on specific issues. Raphael advocated for the development of a disaster mental health research strategy,85 which would include an agreed-upon set of criteria for measurement of important variables that are selected based on the demand they create on participants and researchers, ease of use across diverse disaster contexts, and ability to assess changes longitudinally.

Balaban has presented a useful guide for selecting instruments to assess children’s disaster outcomes.60 Although focused on clinical purposes, his recommendations address concerns about cost and time, and the need to identify a limited set of psychological and behavioral reactions assessed by both self- and parent reports.

Informants vary in the type and quality of information they can provide. In addition to collateral reports provided by parents, siblings, or peers, teachers have the advantage of being able to compare children to their peers.2 In addition, Steinberg and colleagues have suggested that future studies should assess children’s perceptions about their research participation as a means for evaluating the benefits.35

How?

Researchers who incorporate well-defined plans for the “four Ws” in their investigations of child disaster mental health will be better equipped to develop straightforward methodological plans. The procedures for data collection are driven by the purpose (Why), sample (Who), timing (When), and variables selected (What). Existing strategies facilitate “How” researchers will acquire assessment information. The methodological approach employed likely will reflect the distinguishing features of a particular disaster event. A simple illustration of the “four Ws” is depicted in Figure 1, with the “How” discussed below as a guide to determining the steps to take in a study of child disaster mental health.

Figure 1.

The Five Fundamental Questions for Child Disaster Mental Health Research

Determine “Why”

Even in the chaotic aftermath of an event, researchers embark on investigations with certain objectives. To facilitate the data collection process and maximize the application of results, the rationale for the study—to describe, explain, predict, and/or influence—must be defined clearly. In light of the remarkable foundation of empirical knowledge establishing the effects of disasters on children, the literature would benefit from the incorporation of theory, and advancements in our abilities to explain precisely how certain variables contribute to positive and negative outcomes and to influence these outcomes through prevention and intervention efforts.

Although valuable in describing, extant findings have been generated primarily from convenience samples and provide insufficient information for the continued development of theory. To explain child disaster mental health, researchers have conducted comprehensive literature reviews to identify Who, When, and What to study. Determinations of Who and When are defined according to the potential application of findings. Researchers intentionally select variables based on their potential usefulness in explaining factors that contribute to disaster symptomatology and those associated with positive outcomes, such as resilience and posttraumatic growth.

Pre-event data are essential to predict, and disaster-related variables must be isolated to be able to draw conclusions and examine both risk and protective factors. Studies of interventions are designed to influence child disaster mental health. As illustrated in Figure 1, the reasons for conducting studies (Why?) are aligned with the various purposes for conducting research in general. Thus, population descriptions of exposure and reactions and theory testing are conducted to describe, explain, and predict; needs assessment and intervention studies are conducted to explain, predict, and influence.

Identify “Who”

Choosing the appropriate population to study depends, in part, on the issues of concern and the questions being asked, and conversely, specific populations raise distinct issues and generate distinct questions. For example, researchers may select a study population based on some specific characteristic such as demographics (eg, ethnicity of the child) or developmental status, family structure (eg, children of divorce), cultural heritage, geographic location, type and severity of disaster exposure, or source of participants (eg, schools, day care settings).3

Representativeness is an additional issue for consideration, as it enhances researchers’ abilities to draw conclusions about the nature of disaster mental health among the population.24 Practical barriers may limit accessibility to children and their families, which may signify the need for alternative recruiting methods. Fortunately, technological advances (eg, the Internet, mobile phones) have provided researchers with new avenues to reach participants who otherwise may have been excluded. For example, Gil-Rivas and colleagues collected data on a national sample of adolescents and their parents following the September 11 terrorist attacks through the use of a Web-based survey.86

Decide “When”

Retrospective data limit the ability to produce definitive results about any preexisting factors associated with mental health outcomes. When pre-disaster information is unavailable, North and Norris have recommended researchers begin fieldwork within the first few weeks post event in order to capture data that might be lost in later retrospective accounts.3 Quick access is essential to obtaining valuable information about the immediate disaster effects and survivor needs, eliciting more accurate information in “real time.” For research purposes, early data collection allows for the discovery of early predictors of long-term reactions.3 When part of clinical screening processes, early assessments may identify those who are experiencing the most severe initial reactions, and thus, may have the greatest need for intervention.

Early data collection is not without significant obstacles and drawbacks. Entry may be complicated by safety and security concerns, the urgency of clinical needs, ethical standards, and other logistical barriers that must be addressed prior to the commencement of a study. As many exposed individuals experience transient posttraumatic reactions, assessments conducted in the immediate aftermath of an event may be misleading. In the chaos during and/or following an event, survivors typically are preoccupied with safety and other physical needs, and may be burdened by requests to participate in research.3

Resolve “What”

Results from over 30 years of child disaster studies have revealed the importance of assessing a variety of relevant outcomes and predictors. Although perhaps limitless in scope, the most important predictors and correlates identified in previous child disaster research have been summarized. Ascertaining which variables truly predict or cause children’s disaster reactions requires the use of validated assessments and application of careful empirical control. Longitudinal design can provide information to enhance confidence in conclusions regarding the impact of specified factors over time. Importantly, the scope of each inquiry may be tailored to the defining features of the particular disaster event.

Clearly-defined constructs are necessary for consistency across studies, and should contribute to increased validity and reliability of results. Research on children’s disaster experiences should include attention to their functioning and whether they achieve developmental milestones.87 In terms of exposure, an assortment of measures should be utilized, including ones that address objective and subjective factors. Indicators of geographic proximity may help to identify certain features of the sample, but do not fully explain initial disaster reactions or those that persist. Subjective perceptions of life threat, loss, life disruption, and interpersonal relationships with victims complement determinations of geographic proximity. Further investigation of the impact of individual characteristics such as age, development, gender, and predisposition is needed, as well as assessments of parent and family factors. Longitudinal data, including reports from both parents and children, could assist with further interpretation of the associations between parent and child disaster-related symptom presentations. Assessments also should include resilience and positive growth.

Establish “How?”

The assessment modality should be selected carefully in order to obtain the desired information from children and the important others who may provide significant feedback about their functioning. For diagnostic purposes or to enhance existing knowledge about the longitudinal course of disaster reactions, comprehensive assessments should be utilized. Well-defined, briefer measurement tools may be used for clinical screening purposes or to assess novel issues and test new theories. Consideration should be given to developmental factors that influence children’s abilities to participate meaningfully in disaster assessments and that affect the manifestation of symptomatology across various age groups. Parental reports, while necessary for very young children, may elicit information that contradicts that of older children and adolescents, which must be acknowledged and reconciled by researchers.

Conclusions

Research is crucial to advance knowledge in the field and to facilitate the development of services and interventions to address the novel clinical issues that arise in the context of a disaster. Five fundamental questions guide mental health researchers interested in assessing children’s disaster reactions. Critical tasks of research endeavors include identifying the research questions (Why?), populations (Who?), and variables of interest (What?) and determining When to initiate and conclude data collection. By answering the “four Ws,” investigators are better equipped to determine how to proceed (How?).

The past few decades of disaster assessment research have produced a diverse portfolio of studies to guide clinical efforts focused on children. These studies have used a variety of methods from exploratory, qualitative design to those with more experimental control. The Why? of most child disaster studies is to enhance our understanding of disaster reactions with the goal of identifying and developing services and interventions for young survivors and their families. Researchers face numerous practical obstacles in the chaotic and unpredictable disaster environment. Furthermore, with post-disaster environments in particular, the diversity inherent in the populations and events studied presents challenges to the selection of research questions and limitations to the control of errors. Nonetheless, researchers rely on various sources of scientific inquiry, addressing a variety of questions in their research efforts. The purpose of an investigation may determine and be determined by the timing of the study.

The extent to which children are affected by disasters depends on numerous factors, and an accurate evaluation is influenced by study design, sample selection, measurement tools, and targeted outcomes. Researchers are urged to move beyond accepting commonly stated assumptions about the importance of limited variables and conditions (eg, physical proximity) to explore and critically analyze the myriad factors (and their relative influence) that may contribute to the differential vulnerability of children exposed to disasters. Discovering and elucidating the effects of development is a formidable challenge for researchers seeking to understand and assist children exposed to disaster.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Work was funded in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute of Nursing Research, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (R25 MH070569) which established the Child and Family Disaster Research Training and Education Program at the Terrorism and Disaster Center (TDC) at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (Dr. B. Pfefferbaum). TDC is a partner in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and is funded by SAMHSA (U79 SM57278). The National Center for Disaster Mental Health Research, funded by the NIMH (P60 MH082598), also provided funding for the work (Dr. Norris).

Abbreviations

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

References

- 1.Litz BT, Gibson LE. Conducting research on mental health interventions. In: Ritchie EC, Watson PJ, Friedman MJ, editors. Interventions Following Mass Violence and Disasters: Strategies for Mental Health Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Research with children exposed to disasters. Int J Meth Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(2):S49–S56. doi: 10.1002/mpr.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.North CS, Norris FH. Choosing research methods to match research goals in studies of disaster or terrorism. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for Disaster Mental Health. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pynoos RS, Schreiber MD, Steinberg AM, Pfefferbaum BJ. Impact of terrorism on children. In: Sadock BL, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8. II. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 3551–3563. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton D, Hill J, O’Ryan D, et al. Long-term effects of psychological trauma on psychosocial functioning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(5):1007–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goenjian AK, Walling D, Steinberg AM, et al. A prospective study of posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among treated and untreated adolescents 5 years after a catastrophic disaster. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2302–2308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Lucas CP, et al. Psychopathology among New York City public school children 6 months after September 11. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):545–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown EJ, Goodman RF. Childhood traumatic grief: an exploration of the construct in children bereaved on September 11. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;34(2):248–359. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3402_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gil-Rivas V, Holman EA, Silver RC. Adolescent vulnerability following the September 11th terrorist attacks: A study of parents and their children. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8(3):130–142. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koplewicz HS, Vogel JM, Solanto MV, et al. Child and parent response to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(1):77–85. doi: 10.1023/A:1014339513128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McFarlane AC. The relationship between patterns of family interaction and psychiatric disorder in children. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1987;21(3):383–390. doi: 10.1080/00048678709160935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Proctor LJ, Fauchier A, Oliver PH, et al. Family context and young children’s responses to earthquake. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(9):941–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardeña E, Dennis JM, Winkel M, Skitka LJ. A snapshot of terror: acute posttraumatic responses to the September 11 attack. J Trauma Dissoc. 2005;6(2):69–84. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: a prospective study. J Con Clin Psychology. 1996;64(4):712–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lack CW, Sullivan MA. Attributions, coping, and exposure as predictors of long-term posttraumatic distress in tornado-exposed children. J Loss Trauma. 2008;13:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russoniello CV, Skalko TK, O’Brien KO, et al. Childhood posttraumatic stress disorder and efforts to cope after Hurricane Floyd. Behav Med. 2002;28(2):61–71. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernberg EM, La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Prinstein MJ. Prediction of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after hurricane Andrew. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105(2):237–248. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadsworth ME, Gudmundsen GR, Raviv T, et al. Coping with terrorism: age and gender differences in effortful and involuntary responses to September 11th. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8(3):143–157. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. Beyond recovery from trauma: implications for clinical practice and research. J Social Issue. 1998;54(2):357–371. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cryder CH, Kilmer RP, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. An exploratory study of posttraumatic growth in children following a natural disaster. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):65–69. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bannon W, DeVoe ER, Klein TP, Miranda C. Gender as a moderator of the relationship between child exposure to the World Trade Centre disaster and behavioural outcomes. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2009;14(3):121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chemtob CM, Nomura Y, Abramovitz RA. Impact of conjoined exposure to the World Trade Center Attacks and to other traumatic events on the behavioral problems of preschool children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):126–133. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH. Reconsideration of harm’s way: onsets and comorbidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their caregivers following Hurricane Katrina. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(3):508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris FH. Disaster research methods: past progress and future directions. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(2):173–184. doi: 10.1002/jts.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K. Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(12):1057–1063. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desivilya HS, Gal R, Ayalon O. Extent of victimization, traumatic stress symptoms, and adjustment of terrorist assault survivors: a long-term follow-up. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(4):881–889. doi: 10.1007/BF02104110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vila G, Porche LM, Mouren-Simeoni MC. An 18-month longitudinal study of posttraumatic disorders in children who were taken hostage in their school. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(6):746–754. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Kronenberg M, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Katrina: predicting the need for mental health services. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(2):212–220. doi: 10.1037/a0016179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw JA, Applegate B, Tanner S. Psychological effects of Hurricane Andrew on an elementary school population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(9):1185–1192. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw JA, Applegate B, Schorr C. Twenty-one-month follow-up study of school-age children exposed to Hurricane Andrew. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(3):359–364. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199603000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Mandell DJ. Children’s mental health after disasters: the impact of the World Trade Center attack. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2003;5(2):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s11920-003-0026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfefferbaum B, Call JA, Sconzo GM. Mental health services for children in the first two years after the 1995 Oklahoma City terrorist bombing. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(7):956–958. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.7.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindy JD, Grace MC, Green BL. Survivors: outreach to a reluctant population. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1981;51(3):468–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1981.tb01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfefferbaum B, Tucker P, North CS. The Oklahoma City bombing. In: Neria Y, Galea S, Norris F, editors. Mental Health Consequences of Disasters. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 508–521. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Steinberg JR, Pfefferbaum B. Conducting research on children and adolescents after disaster. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yule W, Bolton D, Udwin O, et al. The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: I: The incidence and course of PTSD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):503–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Krug RS. Clinical needs assessment of middle and high school students following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1069–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.7.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silverman WK, La Greca AM. Children experiencing disasters: definitions, reactions, and predictors of outcomes. In: La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Roberts MC, editors. Helping Children Cope with Disasters and Terrorism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Wu P, et al. Exposure to trauma and separation anxiety in children after the WTC attack. Applied Developmental Science. 2004;8(4):172–183. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milgram NA, Toubiana YH, Klingman A, et al. Situational exposure and personal loss in children’s acute and chronic stress reactions to a school bus disaster. J Trauma Stress. 1988;1(3):339–353. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Putnam FW. Special methods for trauma research with children. In: Carlson EB, editor. Trauma Research Methodology. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Institute Press; 1996. pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balaban V. Assessment of children. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA, editors. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breton JJ, Valla JP, Lambert J. Industrial disaster and mental health of children and their parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(2):438–445. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pfefferbaum B, Stuber J, Galea S, Fairbrother G. Panic reactions to terrorist attacks and probable posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(2):217–228. doi: 10.1002/jts.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClellan JM, Werry JS. Introduction. Research psychiatric diagnostic interviews for children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):19–26. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman MJ. Disaster mental health research: Challenges for the future. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 288–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norris FH, Elrod CL. Psychosocial consequences of disaster: A review of past research. In: Norris FH, Galea S, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, editors. Methods for Disaster Mental Health. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaughlin KA, Fairbank JA, Gruber MJ, et al. Serious emotional disturbance among youths exposed to Hurricane Katrina 2 years postdisaster. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1069–1078. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asarnow J, Glynn S, Pynoos RS. When the earth stops shaking: earthquake sequelae among children diagnosed for pre-earthquake psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(8):1016–1023. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Wasserstein SB. Children’s predisaster functioning as a predictor of posttraumatic stress following Hurricane Andrew. J Con Clin Psychology. 1998;66(6):883–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuber J, Galea S, Pfefferbaum B, et al. Behavior problems in New York City’s children after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(2):190–200. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McFarlane AC. Posttraumatic phenomena in a longitudinal study of children following a natural disaster. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26(5):764–769. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McLaughlin KA, Fairbank JA, Gruber MJ. Trends in serious emotional disturbance among youths exposed to Hurricane Katrina. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolton D, O’Ryan D, Udwin O, et al. The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: II: General psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):513–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Green BL, Grace MC, Vary MG, et al. Children of disaster in the second decade: a 17-year follow-up of Buffalo Creek survivors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(1):71–79. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Terr L. Chowchilla revisited: the effects of psychic trauma four years after a school-bus kidnapping. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(12):1543–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.12.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Udwin O, Boyle S, Yule W, et al. Risk factors for long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: predictors of post traumatic stress disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(8):969–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, et al. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfefferbaum B, Houston JB, North CS, Regens JL. Youth’s reactions to disasters and the factors that influence their response. The Prevention Researcher. 2008;15(3):3–6. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.15-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balaban V. Psychological assessment of children in disasters and emergencies. Disasters. 2006;30(2):178–198. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malchiodi CA, Steele W, Kuban C. Resilience and posttraumatic growth in traumatized children. In: Malchiodi CA, editor. Creative Interventions with Traumatized Children. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fairbrother G, Stuber J, Galea S, et al. Posttraumatic stress reactions in New York City children after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):304–311. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0304:psriny>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kennedy C, Charlesworth A, Chen JL. Disaster at a distance: impact of 9.11.01 televised news coverage on mothers’ and children’s health. J Pediatr Nursing. 2004;19(5):329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tivis RD, et al. Television exposure in children after a terrorist incident. Psychiatry. 2001;64(3):202–211. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.202.18462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, Brandt EN, Jr, et al. Media exposure in children one hundred miles from a terrorist bombing. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1023293824492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phillips D, Prince S, Schiebelhut L. Elementary school children’s responses 3 months after the September 11 terrorist attacks: a study in Washington, DC. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74(4):509–528. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the national study of Americans’ reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288(5):581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.La Greca AM, Silverman WK. Treating children and adolescents affected by disasters and terrorism. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and Adolescent Therapy: Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 356–382. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lonigan CJ, Shannon MP, Taylor CM, et al. Children exposed to disaster: II. Risk factors for the development of post-traumatic symptomatology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(1):94–105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJ, Taylor CM. Children exposed to disaster: I. epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms and symptom profiles. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(1):80–93. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weems CF, Watts SE, Marsee MA, et al. The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2295–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lengua LJ, Long AC, Meltzoff AN. Pre-attack stress-load, appraisals and coping in children’s responses to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Earls F, Smith E, Reich W, Jung KG. Investigating psychopathological consequences of a disaster in children: a pilot study incorporating a structured diagnostic interview. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;271(1):90–95. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198801000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garrison CZ, Weinrich MW, Hardin SB, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents after a hurricane. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(7):522–530. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Green BL, Korol M, Grace MC, et al. Children and disaster: Age, gender, and parental effects on PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30(6):945–951. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Children and families in the context of disasters: implications for preparedness and response. The Family Psychologist. 2008;24(2):6–10. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.24-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wolmer L, Laor N, Gershon A, et al. The mother-child dyad facing trauma: a developmental outlook. J Nerv Men Dis. 2000;188(7):409–415. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laor N, Wolmer L, Mayes LC, et al. Israeli preschoolers under Scud missile attacks. A developmental perspective on risk-modifying factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(5):416–423. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050052008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Laor N, Wolmer L, Cohen DJ. Mothers’ functioning and children’s symptoms 5 years after a SCUD missile attack. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(7):1020–1026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wasserstein SB, La Greca AM. Hurricane Andrew: parent conflict as a moderator of children’s adjustment. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1998;20(2):212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garrison CZ, Bryant ES, Addy CL, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents after Hurricane Andrew. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(9):1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part II. Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raphael B. The challenges of purpose in the face of chaos: commentary paper by Professor Beverley Raphael. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(S2):S42–S48. doi: 10.1002/mpr.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gil-Rivas V, Silver RC, Holman EA, et al. Parental response and adolescent adjustment to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1063–1068. doi: 10.1002/jts.20277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weissbecker I, Sephton SE, Martin MB, Simpson DM. Psychological and physiological correlates of stress in children exposed to disaster: current research and recommendations for intervention. Children, Youth and Environments. 2008;18(1):30–70. [Google Scholar]