Abstract

The predominant 18.5-kDa classic myelin basic protein (MBP) is mainly responsible for compaction of the myelin sheath in the central nervous system, but is multifunctional, having numerous interactions with Ca2+-calmodulin, actin, tubulin, and SH3-domains, and can tether these proteins to a lipid membrane in vitro. The full-length 21.5-kDa MBP isoform has an additional 26 residues encoded by exon-II of the classic gene, which causes it to be trafficked to the nucleus of oligodendrocytes (OLGs). We have performed site-directed mutagenesis of selected residues within this segment in red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged constructs, which were then transfected into the immortalized N19-OLG cell line to view protein localization using epifluorescence microscopy. We found that 21.5-kDa MBP contains two nontraditional PY-nuclear-localization signals, and that arginine and lysine residues within these motifs were involved in subcellular trafficking of this protein to the nucleus, where it may have functional roles during myelinogenesis.

Keywords: Myelin basic protein (MBP), Gene of oligodendrocyte lineage (Golli), Nuclear targeting, Oligodendrocytes, Myelination, Live-cell imaging

1. Introduction

Oligodendrocytes (OLGs) are glial cells in the brain and spinal cord (CNS – central nervous system), which are essential for the production of myelin, a lipid-rich structure behaving as an electrical insulator that facilitates saltatory conduction of neuronal action potentials [1,2]. One of the major families of proteins of CNS myelin arises from the Golli (Gene of Oligodendrocyte Lineage) complex, which is responsible for the developmentally-regulated production of early developmental Golli proteins, and classic myelin basic proteins (MBPs) [3–5]. The classic MBP isoforms arise from transcription start site 3 of Golli and are nominally 14-kDa, 17.22/17.24- kDa, 18.5-kDa, and 21.5-kDa in mammals [6,7], and are essential for the formation of compact CNS myelin by OLGs [8,9]. The 18.5- kDa isoform predominates in adult human myelin and has been the most studied. Its main purpose is adhesion of the cytoplasmic leaflets of OLG membranes [8] to form a “molecular sieve” [10,11]. However, this protein is multifunctional and interacts with numerous other proteins including actin, tubulin, Ca2+-activated calmodulin, and SH3-domain proteins (reviewed in [12–19]).

Our group has recently shown that unmodified and charge variants of the classic 18.5-kDa MBP isoform (Fig. 1A) significantly decrease calcium influx, via voltage operated calcium channels into primary OLGs and immortalized N19-OLG cells, in contrast to Golli isoforms [20], and that stimulation with a phorbol ester (phorbol- 12-myristate-13-acetate), and with IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor- 1), spatially redistributes MBP to distinct membrane ‘ruffled’ regions at the cell cortex, where it associates with β- and γ-actin, cortactin, and α-tubulin [21]. Additionally, we have shown that the expression of classic 18.5-kDa MBP with the constitutively-active form of Fyn–kinase causes extensive membrane elaboration, and branching complexity at the forefront of extending N19-OLG membrane processes, a phenomenon that is abolished by substituting either proline residue within its PXXP SH3-ligand consensus motif [22]. These results demonstrate that 18.5-kDa MBP participates in and/or mediates cytoskeletal protein–protein interactions at the cytoplasmic leaflet during membrane remodeling in developing OLGs, and that several of these interactions may be facilitated by SH3-ligand domain binding of MBP with other proteins. In all of these in cellulo experiments, the constructs had a fluorescent protein fused to the amino terminus, and a 21-nucleotide untranslated region (UTR) was added to the 3′-end of the gene to ensure proper trafficking of the 18.5-kDa isoforms to the cell periphery [20–24].

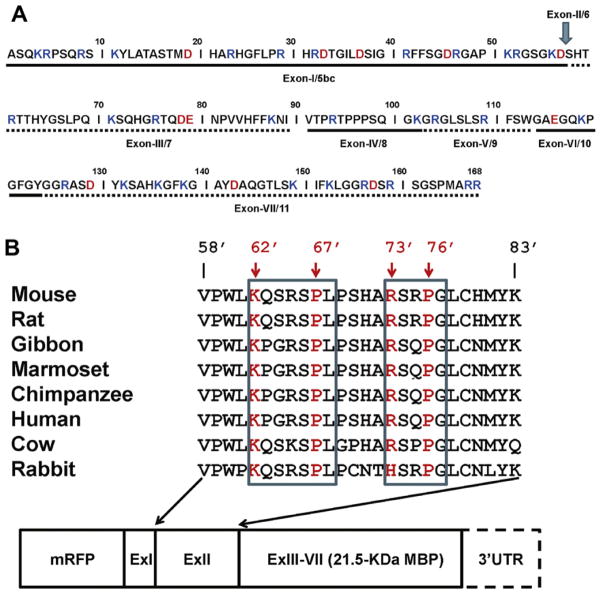

Fig. 1.

(A) Amino acid sequence and exon arrangement of the classic 18.5-kDa MBP from the mouse. The exons are delimited by alternating solid or dashed lines. Basic residues are colored blue and acidic residues are colored red. The amino acid numbering omits the N-terminal methionyl residue which is cleaved post-translationally, and follows our standard convention [15–17]. (B) ClustalW2 alignment of the conserved regions encoded by exon-II of 21.5-kDa MBP in various species. Here, the residue numbers are primed to distinguish them from the 18.5-kDa numbering in panel (A) for which we have established a convention. Two putative PY-NLS motifs are identified with the pattern of ZX2–5PB, where “Z” is a basic residue, “X” is any residue, and “B” is a hydrophobic residue. The amino acid residues which were subjected to substitution are highlighted in red. These residues are highly conserved among these species, with the exception of the histidine residue found in the second putative motif in the rabbit genome. The 21-nucleotide 3′-untranslated region (UTR) is the minimal sequence responsible for transport and localization of MBP mRNA within OLGs, including the transfected N19-cells used here [20–22]. (For interpretation of references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Classic MBP occurs as several other size isoforms in addition to the 18.5-kDa form due to alternative splicing of a single mRNA transcript. This process results in two minor MBP transcripts, 21.5- kDa MBP and 17.22-kDa MBP in the mouse, and 21.5-kDa and 20.2- kDa MBP in the human, containing 26 amino acids encoded by exon-II of the classic MBP gene (called exon-6 in Golli numbering, Fig. 1B). Their expression is enriched during active early myelination in the human and mouse, and in immature OLGs in culture [5–7]. These minor MBP isoforms have been observed in the nucleus of primary OLG cultures and OLGs in the mouse brain [25– 27] and are also enriched in the radial component of compact myelin [28,29]. We have found that full-length 21.5-kDa MBP was still localized primarily to the nucleus despite the presence of the 3′UTR [20–22]. The minor isoforms have been speculated to play key developmental roles that may regulate myelinogenesis [25,27,30–32].

The exon-II-encoded sequence likely contains a nuclear-localization signal (NLS), but no traditional NLS containing stretches of two or more basic residues is present (Fig. 1B). It has been shown that Golli proteins, which arise from transcription start site 1 of the same gene complex as MBP, but are expressed earlier in development, have a non-traditional nuclear-localization signal (NLS) contained within amino acids 1–36 of the classic MBP portion (Fig. 1A) [33]. However, this non-traditional NLS encoded within exon-I of classic MBP does not cause 18.5-kDa MBP to be localized in the nucleus, and presumably is also not responsible for the localization of 21.5-kDa MBP in the nucleus. In this current study, we have examined and identified a non-traditional NLS contained within the segment encoded by exon-II of classic 21.5-kDa MBP.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmids

Previously described plasmids coding for RFP-tagged versions of 21.5-kDa MBPs possessing a 21-nt 3′UTR were used throughout these investigations, and site-directed mutagenesis was performed as previously described [20–22]. The resulting constructs were confirmed by sequencing (Laboratory Services Division, University of Guelph, ON) and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constructs of RFP-tagged murine 21.5-kDa MBP, containing a 3′UTR, with point substitutions in the exon-II-encoded segment hypothesized to comprise the NLS. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the polymerase chain reaction. Here, “F” denotes forward primer and “R” denotes reverse primer. All primers were ordered from the University of Guelph Laboratory Services Division. Amino acids within the putative PY-NLS motifs in exon-II of 21.5-kDa MBP were substituted singularly, and in tandem, with glycine or glutamic acid. Single substitution with glycine residues had no significant effect on nuclear-localization in some instances (indicated with a +). Other substitutions, single and tandem, resulted in a decrease in nuclear-localization (indicated with a +/−). The greatest degree of exclusion of 21.5-kDa MBP from the nucleus was seen with a tandem substitution of two positively-charged residues (indicated with a −).

| Name of construct | Primers used | Residue mutation | Nuclear-localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔP67′G | F: 5′cagagccggagcggtctgccctctcatgcc 3′ R: 5′ggcatgagagggcagaccgctccggctctg 3′ | P67′→G67′ | + |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔP76′G | F: 5′cagagccggagcggtctgccctctcatgcc 3′ R: 5′ggcatgagagggcagaccgctccggctctg 3′ F: 5′gcccgcagccgtggtggactgtgccac 3′ R: 5′gtggcacagtccaccacggctgcgggc 3′ |

P76′*rarr;G76′ | + |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔP67′ΔP76′G | F: 5′gcccgcagccgtggtggactgtgccac 3′ R: 5′gtggcacagtccaccacggctgcgggc 3′ | P67′→G67′, P76′→G76′ | +/− |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔK62′G | F: 5′ gtaccctggctagggcagagccggagc 3′ R: 5′ gctccggctctgccctagccagggtac 3′ | K62′→G62′ | +/− |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔR73′G | F: 5′ ccctctcatgccggcagccgtcctggactg 3′ R: 5′ cagtccaggacggctgccggcatgagaggg 3′ | R73′→G73′ | + |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔK62′E | F: 5′ gtaccctggctagagcagagccggagc 3′ R: 5′ gctccggctctgctctagccagggtac 3′ | K62′→E62′ | +/− |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔR73′E | F: 5′ ccctctcatgccgagagccgtcctggactg 3′ R: 5′ cagtccaggacggctctcggcatgagaggg 3′ | R73′→E73′ | +/− |

| pERFP-C1-RFP-MBP-21.5-UTR ΔK62′EΔR73′E | F: 5′ gtaccctggctagagcagagccggagc 3′ R: 5′ gctccggctctgctctagccagggtac 3′ F: 5′ ccctctcatgccgagagccgtcctggactg 3′ R: 5′ cagtccaggacggctctcggcatgagaggg 3′ |

K62′→E62′, R73′→E73′ | − |

2.2. N19-OLG cell culture and transfection

The N19-OLG cell lines, cell culture, and transfection were performed as previously described [20]. Tissue culture reagents were purchased from either Gibco/Invitrogen (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Burlington, ON) or Sigma–Aldrich (Oakville, ON) unless otherwise stated. For transfection experiments, DNA was purified using the PureLink HiPure Plasmid Purification kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Burlington, ON). The FuGene HD transfection reagent was purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). The immortalized N19-OLG cell lines [34–36] were grown in DMEM high-glucose media supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and cultured in 10 cm plates at 34 °C/5% CO2. At 70–80% confluency (4–7 days), cells were detached using 0.25% trypsin for 5 min. Using a haemocytometer, live cells were counted, plated at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/mL, and grown overnight in preparation for transfection experiments. The following day, the cells were transfected using 100 μL serum-free media, 2.0 μg of plasmid DNA, and 4 μL of FuGene HD (Roche Diagnostics). The DNA was allowed to complex for 5 min at room temperature, and was directly added to cells following incubation. Cells were cultured for an additional 72 h at 34 °C prior to fixation, or immunoprocessing.

2.3. Immunofluorescence microscopy and image analyses

Following protein expression, untreated cells were directly fixed using 4% formaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) solution for 15 min with gentle rocking. The slides were then washed two times with 1 mL PBS, and were mounted on glass slides using ProLong™ Gold AntiFade reagent containing DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Invitrogen). After incubating for 30 min, slides were viewed using a Leica epifluorescence microscope (DMRA2). Images were processed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/)), and were compiled using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

3. Results and discussion

Most nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins in the cell is carried out by the Karyopherin-β (Kapβ) family of nuclear transport proteins, which recognize nuclear-localization signals (NLS) and nuclear-export signals (NES) on other proteins to carry out such transport [37–39]. Pedraza et al. (1997) showed that not only is 21.5-kDa MBP located in the nucleus of OLGs, it is actively transported there, in an energy- as well as temperature-dependent process [31,32]. Our goal here was to elucidate the NLS in this isoform. The conditionally-immortalized N19 oligodendroglial line was chosen as a relevant stage-specific cell line to examine the translocation of this MBP isoform in tissue culture [36]. This cell line stains positive for both the NG2 and A2B5 antigens, which are markers for oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPCs), and lacks expression of classic MBP and proteolipid protein mRNAs [35]. The N19-OLG line has been successfully employed in other studies, including specifically examining the effect of Golli and classic 18.5- kDa MBP over-expression on calcium homeostasis [13,20,40,41], and on the co-localization of 18.5-kDa MBP with cytoskeletal proteins and SH3-domain-containing proteins [21,22].

There are two types of well-established NLSs, although there may be more that are as yet undiscovered. The first classical NLS is composed of 1 or 2 stretches of positively-charged amino acids, often lysine-rich [39,42]. Another type is the bipartite NLS, which consists of two basic residues, a spacer consisting of 10 residues, and another basic region consisting of at least three basic residues out of five [43]. Recently, a new diverse class of NLS motifs has been elucidated, termed the PY-NLS. This motif is defined by an N-terminal hydrophobic or basic motif, and a C-terminal RX2–5PY motif, where Y can also be other hydrophobic amino acids or glycine [39]. Sequence alignments from the exon-II-encoded region of 21.5-kDa MBP are shown in Fig. 1B. Although there are no stretches of 2 or more basic residues characteristic of the classical or bipartite NLS, it can be seen that this segment contains two putative PY-NLS motifs with L or G instead of Y. It has been observed that hydrophobic amino acids are well-tolerated in place of the tyrosine in the RX2-5PY motif, e.g., the PY-motif cargos Nab2 and HuR that have PL- and PG-dipeptides, respectively [37,38]. Here, in 21.5-kDa MBP, the 10 amino acids preceding the exon-II-encoded segment contain four basic residues, thus completing the required characteristics of a PY motif (see Fig. 1A).

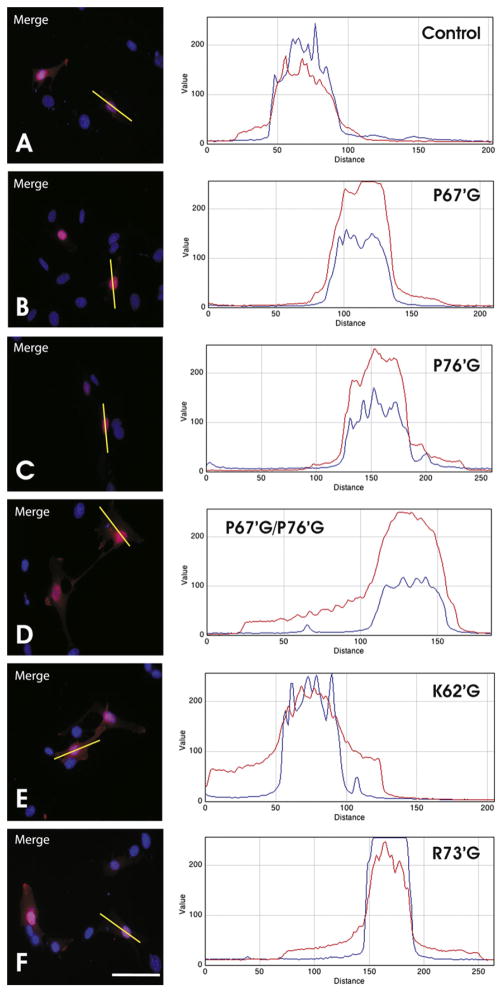

To determine whether these putative PY-NLS motifs in the exon-II-encoded region were responsible for trafficking 21.5-kDa MBP to the cell nucleus, we constructed a number of amino acid residue substitutions within these segments in RFP-tagged constructs that targeted key residues that could be involved in nuclear transport (Table 1). By using site-directed mutagenesis, we substituted these amino acid residues with either glycine (ΔP→G neutral), or in some instances to glutamic acid (ΔK/R→E negatively-charged) to reverse the positively-charged residues that may be directly involved in Karyopherin-β binding. These constructs were then transfected into the immortalized N19-OLG cell line to view protein localization using epifluorescence microscopy. Single glycine substitutions at sites ΔP67′G and ΔP76′G did not cause any noticeable differences in the trafficking of 21.5-kDa MBP to the nucleus compared to the unmodified control (Fig. 2A–C). The tandem mutation ΔP67′GΔP76′G, however, did show a diminution of nuclear-localization (Fig. 2D). Single glycine substitutes targeting the positively-charged residues with the putative PY-NLS at position ΔK62′G and ΔR73′G decreased the efficiency of 21.5-kDa MBP trafficking to the nucleus in the former but not the latter case (Fig. 2E and F).

Fig. 2.

Fluorescence intensity trace analysis of nucleocytoplasmic distribution of 21.5-kDa MBP in the N19-OLG cell line. All cells were transfected with 2.0 μg of RFP-tagged plasmid DNA and a nuclear stain, DAPI, seen in blue. Only the merged images are shown. Each trace indicates fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units, versus distance in pixels. The blue line represents DAPI staining, and the red line represents MBP. Each cell is representative of the predominant protein localization phenotype observed in all of the transfected cells observed. Transfection with RFP-tagged 21.5-kDa MBP (panel A) shows little cytosolic presence of 21.5-kDa MBP, indicating its transport to the nucleus, as previously observed [20–22]. The same pattern can be seen in cells transfected with RFP-tagged 21.5-kDa MBP constructs containing the single substitutions ΔP67′G, ΔP76′G, and ΔR73′G (panels B, C, and F, respectively). Cells transfected with constructs containing tandem ΔP67′G and ΔP76′G substitutions, or a single ΔK62′G substitution, (panels D and E, respectively), show a slight shift from nuclear to cytoplasmic presence of 21.5-kDa MBP. Scale bar = 40 μm. (For interpretation of references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

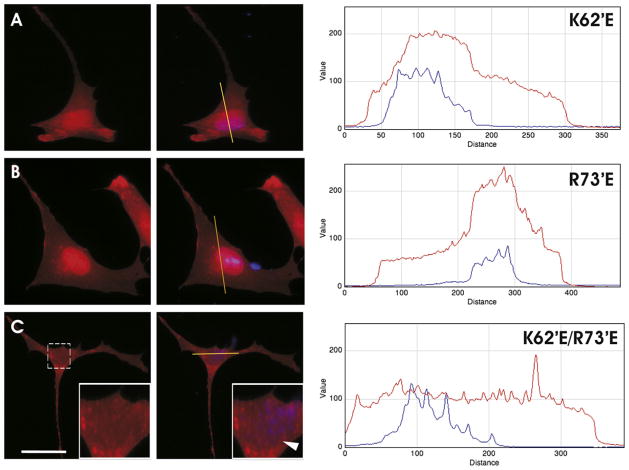

We chose next to explore further the role of these positivelycharged residues. When they were altered to glutamic acid (ΔK62′E and ΔR73′E), there was a noticeable increase of 21.5-kDa MBP localization within the cytoplasm and plasma membrane when expressed in N19-OLGs, compared to unmodified 21.5-kDa MBP (Fig. 3A and B). The tandem mutation ΔK62′EΔR73′E resulted in apparently complete loss of trafficking of 21.5-kDa MBP to the nucleus in all transfected cells in culture (Fig. 3C), suggesting that these charged residues encoded by exon-II are important for this trafficking. These results indicate that 21.5-kDa MBP may contain two PY-NLSs that regulate its subcellular localization.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence micrographs and intensity trace analysis of nucleocytoplasmic distribution of 21.5-kDa MBP in the N19-OLG cell line. All cells were transfected with 2.0 μg of RFP-tagged plasmid DNA and a nuclear stain, DAPI, seen in blue. Each trace indicates fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units, versus distance in pixels. The red fluorescence images are shown in the first column, whereas merged images are shown in the second column. Transfection with RFP-tagged 21.5-kDa MBP with the substitutions (A) ΔK62′E, (B) ΔR73′E, and (C) ΔK62′E and ΔR73′E, shows both nuclear and cytosolic presence of 21.5-kDa MBP, indicating a decrease in nuclear-localization of the protein. Each trace indicates fluorescence intensity in number of pixels. The blue line represents DAPI staining, and the red line represents 21.5-kDa MBP. Each cell is representative of the predominant protein localization phenotype observed in all (100%) of the transfected cells observed. Scale bar = 20 μm. (For interpretation of references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Although the 21.5-kDa MBP isoform is intrinsically disordered like 18.5-kDa MBP, far less is known about its structural dynamics and possible self-association, and it is worthwhile to explore the effects of these mutations by NMR spectroscopy [14,15,44]. It has also been suggested that the phosphorylation status of several potential protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation sites within the N-terminal region of MBP may modulate their subcellular localization in OLGs [20,22,31–33,45], another phenomenon worthy of further exploration.

There have been many studies to suggest that alterations in nuclear transport of transcription factors can be a potential mechanism for neuronal degeneration in neurodegenerative disorders [42]. The regulation of MBP isoforms, and the shift in isoform expression, and thus intracellular localization, may play a key developmental role in oligodendrocyte differentiation [46,47]. The exon-II-containing 21.5-kDa and 17.22-kDa MBP isoforms, and possibly specific isoforms of myelin oligodendrocyte basic protein (MOBP), may also have specific functional, not solely structural, roles in the radial component of mature myelin (see [29]). The role of exon-II encoded isoforms of classic MBP in the nucleus and their localization in myelination, and in neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, requires further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP #86483, J.M.B. and G.H.), and a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC, G.H., RG121541). G.H. is a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair. G.S.T.S. is a recipient of Doctoral Studentship from the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada. The authors are grateful to Dr. Nina Jones for the use of her cell culture facilities, to Dr. Reihua (Ray) Lu for generous use of his epifluorescence microscope, and to Mrs. Janine Voyer-Grant for superb technical support.

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- DAPI

4′,6-diaminido-2-phenylin-dole

- Golli

gene of oligodendrocyte lineage

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- NLS

nuclear-localization/import signal

- OLG

oligodendrocyte

- OPC

oligodendroglial progenitor cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PKC

protein kinase C

- RFP

red fluorescent protein

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- 1.Bunge RP. Glial cells and the central myelin sheath. Physiol Rev. 1968;48:197–251. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1968.48.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quarles RH, Macklin WB, Morell P. Myelin formation structure and biochemistry. In: Siegel GJ, Albers RW, Brady ST, Price DL, editors. Basic Neurochemistry–Molecular Cellular and Medical Aspects. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego: 2006. pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campagnoni AT, Pribyl TM, Campagnoni CW, Kampf K, Amur-Umarjee S, Landry CF, Handley VW, Newman SL, Garbay B, Kitamura K. Structure and developmental regulation of golli-mbp, a 105-kilobase gene that encompasses the myelin basic protein gene and is expressed in cells in the oligodendrocyte lineage in the brain. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4930–4938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pribyl TM, Campagnoni CW, Kampf K, Kashima T, Handley VW, McMahon J, Campagnoni AT. The human myelin basic protein gene is included within a 179-kilobase transcription unit: expression in the immune and central nervous systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10695–10699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Givogri MI, Bongarzone ER, Schonmann V, Campagnoni AT. Expression and regulation of golli products of myelin basic protein gene during in vitro development of oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:679–690. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamholz J, de Ferra F, Puckett C, Lazzarini R. Identification of three forms of human myelin basic protein by cDNA cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4962–4966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Ferra F, Engh H, Hudson L, Kamholz J, Puckett C, Molineaux S, Lazzarini RA. Alternative splicing accounts for the four forms of myelin basic protein. Cell. 1985;43:721–727. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Readhead C, Hood L. The dysmyelinating mouse mutations shiverer (shi) and myelin deficient (shimld) Behav Genet. 1990;20:213–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01067791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzner D, Schneider A, Kippert A, Mobius W, Willig KI, Hell SW, Bunt G, Gaus K, Simons M. Myelin basic protein-dependent plasma membrane reorganization in the formation of myelin. EMBO J. 2006;25:5037–5048. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggarwal S, Yurlova L, Simons M. Central nervous system myelin structure synthesis and assembly. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aggarwal S, Yurlova L, Snaidero N, Reetz C, Frey S, Zimmermann J, Pahler G, Janshoff A, Friedrichs J, Muller DJ, Goebel C, Simons M. A size barrier limits protein diffusion at the cell surface to generate lipid-rich myelin-membrane sheets. Dev Cell. 2011;21:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boggs JM. Myelin Basic Protein. Nova Science Publishers; Hauppauge, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulton D, Paez PM, Campagnoni AT. The multiple roles of myelin protein genes during the development of the oligodendrocyte. ASN Neuro. 2010;2:e00027. doi: 10.1042/AN20090051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libich DS, Ahmed MAM, Zhong L, Bamm VV, Ladizhansky V, Harauz G. Fuzzy complexes of myelin basic protein–NMR spectroscopic investigations of a polymorphic organizational linker of the central nervous system. Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;88(Special issue):143–155. doi: 10.1139/o09-123. on Protein Folding: Principles and Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harauz G, Libich DS. The classic basic protein of myelin - conserved structural motifs and the dynamic molecular barcode involved in membrane adhesion and protein–protein interactions. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2009;10:196–215. doi: 10.2174/138920309788452218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harauz G, Ladizhansky V, Boggs JM. Structural polymorphism and multifunctionality of myelin basic protein. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8094–8104. doi: 10.1021/bi901005f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harauz G, Ishiyama N, Hill CMD, Bates IR, Libich DS, Farès C. Myelin basic protein – diverse conformational states of an intrinsically unstructured protein and its roles in myelin assembly and multiple sclerosis. Micron. 2004;35:503–542. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campagnoni AT, Skoff RP. The pathobiology of myelin mutants reveal novel biological functions of the MBP and PLP genes. Brain Pathol. 2001;11:74–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boggs JM. Myelin basic protein: a multifunctional protein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1945–1961. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith GST, Paez PM, Spreuer V, Campagnoni CW, Boggs JM, Campagnoni AT, Harauz G. Classical 18.5- and 21.5-kDa isoforms of myelin basic protein inhibit calcium influx into oligodendroglial cells in contrast to golli isoforms. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:467–480. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith GST, Homchaudhuri L, Boggs JM, Harauz G. Classic 185- and 215-kDa myelin basic protein isoforms associate with cytoskeletal and SH3-domain proteins in the immortalized N19-oligodendroglial cell line stimulated by phorbol ester and IGF-1. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:1277–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith GST, De Avila M, Paez PM, Spreuer V, Wills MK, Jones N, Boggs JM, Harauz G. Proline substitutions and threonine pseudophosphorylation of the SH3 ligand of 18.5-kDa myelin basic protein decrease its affinity for the Fyn- SH3 domain and alter process development and protein localization in oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90:28–47. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson JH, Gao Y, Tatavarty V, Levin MK, Korza G, Francone VP, Kosturko LD, Maggipinto MJ, Barbarese E. Multiplexed RNA trafficking in oligodendrocytes and neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1779:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ainger K, Avossa D, Diana AS, Barry C, Barbarese E, Carson JH. Transport and localization elements in myelin basic protein mRNA. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1077–1087. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allinquant B, Staugaitis SM, D’Urso D, Colman DR. The ectopic expression of myelin basic protein isoforms in Shiverer oligodendrocytes: implications for myelinogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:393–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardy RJ, Lazzarini RA, Colman DR, Friedrich VL., Jr Cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of myelin basic proteins reveals heterogeneity among oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1996;46:246–257. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961015)46:2<246::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staugaitis SM, Colman DR, Pedraza L. Membrane adhesion and other functions for the myelin basic proteins. Bioessays. 1996;18:13–18. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karthigasan J, Kosaras B, Nguyen J, Kirschner DA. Protein and lipid composition of radial component-enriched CNS myelin. J Neurochem. 1994;62:1203–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeBruin LS, Harauz G. White matter rafting – membrane microdomains in myelin. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colman DR, Staugaitis SM, D’Urso D, Sinoway MP, Allinquant B, Bernier L, Mentaberry A, Stempak JG, Brophy PJ. Physiologic properties of myelin proteins revealed by their expression in nonglial cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;605:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedraza L, Fidler L, Staugaitis SM, Colman DR. The active transport of myelin basic protein into the nucleus suggests a regulatory role in myelination. Neuron. 1997;18:579–589. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedraza L. Nuclear transport of myelin basic protein. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:258–264. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971015)50:2<258::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes SD, Campagnoni AT. Two separate domains in the golli myelin basic proteins are responsible for nuclear targeting and process extension in transfected cells. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:587–596. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster LM, Landry C, Phan T, Campagnoni AT. Conditionally immortalized oligodendrocyte cell lines migrate to different brain regions and elaborate ‘myelin-like’ membranes after transplantation into neonatal shiverer mouse brains. Dev Neurosci. 1995;17:160–170. doi: 10.1159/000111284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster LM, Phan T, Verity AN, Bredesen D, Campagnoni AT. Generation and analysis of normal and shiverer temperature-sensitive immortalized cell lines exhibiting phenotypic characteristics of oligodendrocytes at several stages of differentiation. Dev Neurosci. 1993;15:100–109. doi: 10.1159/000111322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verity AN, Bredesen D, Vonderscher C, Handley VW, Campagnoni AT. Expression of myelin protein genes and other myelin components in an oligodendrocytic cell line conditionally immortalized with a temperature-sensitive retrovirus. J Neurochem. 1993;60:577–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suël KE, Gu H, Chook YM. Modular organization and combinatorial energetics of proline–tyrosine nuclear localization signals. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu D, Farmer A, Chook YM. Recognition of nuclear targeting signals by Karyopherin-beta proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chook YM, Suel KE. Nuclear import by karyopherin – betas recognition and inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;18(13):1593–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paez PM, Spreuer V, Handley V, Feng JM, Campagnoni C, Campagnoni AT. Increased expression of golli myelin basic proteins enhances calcium influx into oligodendroglial cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12690–12699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2381-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobs EC, Reyes SD, Campagnoni CW, Givogri I, Kampf K, Handley V, Spreuer V, Fisher R, Macklin W, Campagnoni AT. Targeted overexpression of a golli–myelin basic protein isoform to oligodendrocytes results in aberrant oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. ASN Neuro. 2009;1:e00017. doi: 10.1042/AN20090029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel VP, Chu CT. Nuclear transport oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4:215–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robbins J, Dilworth SM, Laskey RA, Dingwall C. Two interdependent basic domains in nucleoplasmin nuclear targeting sequence: identification of a class of bipartite nuclear targeting sequence. Cell. 1991;64:615–623. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Libich DS, Harauz G. Backbone dynamics of the 18.5 kDa isoform of myelin basic protein reveals transient α-helices and a calmodulin-binding site. Biophys J. 2008;94:4847–4866. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeBruin LS, Haines JD, Bienzle D, Harauz G. Partitioning of myelin basic protein into membrane microdomains in a spontaneously demyelinating mouse model for multiple sclerosis. Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;84:993–1005. doi: 10.1139/o06-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akiyama K, Ichinose S, Omori A, Sakurai Y, Asou H. Study of expression of myelin basic proteins (MBPs) in developing rat brain using a novel antibody reacting with four major isoforms of MBP. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:19–28. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Vries H, de Jonge JC, Schrage C, van der Haar ME, Hoekstra D. Differential and cell development-dependent localization of myelin mRNAs in oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:479–488. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970301)47:5<479::aid-jnr3>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]