Abstract

Racial discrimination has serious negative consequences for the adjustment of African American adolescents. Taking an ecological approach, this study examined the linkages between perceived racial discrimination within and outside of the neighborhood and urban adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and tested whether neighborhood cohesion operated as a protective factor. Data came from 461 African American adolescents (mean age = 15.24 years, SD = 1.56; 50% female) participating in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods. Multilevel models revealed that perceived discrimination within youth’s neighborhoods was positively related to externalizing, and discrimination both within and outside of youth’s neighborhoods predicted greater internalizing problems. Neighborhood cohesion moderated the association between within-neighborhood discrimination and externalizing. Specifically, high neighborhood cohesion attenuated the association between within-neighborhood discrimination and externalizing. The discussion centers on the implications of proximal stressors and neighborhood cohesion for African American adolescents’ adjustment.

Keywords: Racial discrimination, African American adolescents, externalizing, internalizing, neighborhood cohesion

Adolescence is an important period in which to study the implications of racial discrimination for the adjustment of African Americans, as it is a developmental stage when youth spend more time outside of the home (for a review, see Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), and identification with racial/ethnic groups becomes more pronounced (Phinney, 1990). Both increased contact with members of other racial/ethnic groups (Fischer, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000) and a stronger sense of African American identity (Shelton & Sellers, 2000) have been found to increase the likelihood of experiencing racial discrimination. Racial discrimination, a common experience for members of minority groups (Garcia Coll et al., 1996), is especially prevalent among African American youth: By the time they reach adolescence, most African Americans have experienced at least one incident of discrimination (Brody et al., 2006; Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004). Not surprisingly, discrimination is linked to a wide range of adjustment problems for African American adolescents, including internalizing (Clark, Coleman, & Novak, 2004; DuBois, Burk-Braxton, Swenson, Tevendale, & Hardesty, 2002; Lewin, Mitchell, Rasmussen, Sanders-Phillips, & Joseph, 2011; Simons, Murry, McLyod, Lin, Cutrona, & Conger, 2002) and externalizing (DuBois et al., 2002; McCord & Ensminger, 2002; Simons, Chen, Stewart, & Brody, 2003; Simons et al., 2006) problems. However, some youth are more resilient to discrimination than others, which may be due to variation in the context in which discrimination experiences take place.

An ecological perspective underscores the role of social context for developmental processes (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Accordingly, the implications of discrimination may depend on where it occurs (Feagin, 1991; Fisher et al., 2000). The neighborhood is a primary context for adolescent development, as youth become increasingly independent and spend more time outside of the home than they did as children (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Existing research, however, typically measures discrimination in terms of how often, rather than where, it is experienced; as a result, it is not known whether the consequences of discrimination vary according to whether it occurs within versus outside youth’s neighborhood of residence. Understanding the implications of neighborhood contexts for discrimination is important in light of the fact that youth spend a good deal of time outside their own neighborhoods (Burton & Price-Spratlen, 1999). Thus, the first goal of the present study was to examine whether the association between adolescents’ experiences of discrimination and their adjustment (externalizing and internalizing) problems differed according to whether the discrimination occurred within or outside their neighborhood.

The links between discrimination and adjustment also may be contingent on the presence of protective factors in youth’s neighborhoods. Neighborhood cohesion, defined by trust and feelings of kinship among community members (e.g., Sampson, 2008), has been shown to buffer youth from neighborhood stressors including poverty and exposure to violence (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996). Only one study, to our knowledge, has examined whether neighborhood cohesion protects against racial discrimination (Lewin et al, 2011), but it focused exclusively on African American young mothers and did not consider whether the discrimination occurred within individuals’ own neighborhoods. It is possible that the protective effects of cohesion in adolescents’ neighborhoods apply principally, or even exclusively, to discrimination experienced within that neighborhood. Thus, the second goal of our study was to examine whether neighborhood cohesion moderated associations between discrimination – both within and outside of the neighborhood – and youth adjustment.

Contexts for Racial Discrimination and Links to Adolescent Adjustment

By and large, past research on African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences indicates that discrimination is a stressor that interferes with adolescents’ emotional and behavioral functioning. At a time in development when youth are beginning to explore their identities, the meaning of ethnic group membership becomes increasingly salient (Phinney, 1990). Negative racial messages can challenge the developing self-concepts of African American adolescents. Indeed, stressors that threaten a key aspect of adolescents’ identity can be the most damaging (Thoits, 1995). In this light, there is growing evidence that frequent experiences of discrimination undermine adolescent self-worth and heighten fear and anxiety (Rumbaut, 1994; Simons et al., 2002). For example, longitudinal work by Sellers and Shelton (2003) reveals a positive association between the frequency of discrimination experienced and subsequent psychological distress of African American adolescents. Although research documenting links between adolescents’ discrimination experiences and externalizing behaviors is more limited, a study by Brody and colleagues (2006) found positive links between the frequency of African American adolescents’ discrimination experiences and conduct problems. This work suggests that discrimination also may incite feelings of anger and hostility which manifest as acts of delinquency.

Given adolescents’ increased involvement in settings outside of the home, it is important to understand where discrimination occurs and whether its implications vary according to where it takes place. Although research has yet to consider the implications of discrimination that occurs within versus outside of one’s neighborhood, there is some indication that context matters: In a qualitative study, Feagin (1991) found that African American adults who encountered discrimination in public accommodations (such as restaurants) responded with either verbal confrontation or withdrawal, whereas those who experienced discrimination in the street responded with withdrawal or resigned acceptance. In a study of African American adolescents, the distress related to discrimination that occurred in school and peer contexts was associated with lower self-esteem, while the distress associated with exposure to discrimination in institutional contexts (e.g., restaurants, stores) was not (Fisher et al., 2000). These studies indicate that the experience of discrimination may take on meaning according to the setting in which it occurs. In particular, the findings of Fisher and colleagues (2000) suggest that the experience of discrimination has greater personal salience when it occurs in a context that contributes a great deal to adolescents’ personal identity, such as school or peers (Harter, 1990). This notion is consistent with theory and research with adolescents suggesting that stressors like discrimination have stronger negative effects when they occur in proximal or familiar settings or threaten important activities or identities (Agnew, 2001; 2002).

Neighborhoods may be another context with salience for adolescents’ personal identity, given that they shape residents’ social identities and life experiences (Forrest & Kearns, 2001). According to theories of community (McMillan & Chavis, 1986), the relational element of community membership is marked by a feeling of belonging and shared sense of personal relatedness. Boundaries define who belongs and who does not and foster the development of a collective identity (Forrest & Kearns, 2001) and emotional security within a community (Ehrlich & Graeven, 1971). To the extent that adolescents feel that they are members of their neighborhood community, discrimination that occurs within the boundaries of that neighborhood may be more likely to lead to adjustment problems if it challenges adolescents’ expectations about living in a trusted environment. A breakdown in emotional security may undermine healthy self-concept and lead to anxiety and feelings of hopelessness (internalizing problems) or acting-out behaviors (externalizing problems). In contrast, experiences of discrimination outside youth’s neighborhood might have weaker effects on adjustment because they do not disrupt expectations of mutual trust and collective identity. Such experiences may be upsetting but should not evoke the same level of distress as an experience that threatens youth’s trust in their neighborhood and sense of belonging.

The Moderating Role of Neighborhood Cohesion

With the growth of theory and research linking neighborhood context with adolescent internalizing (e.g., Xue, Leventhal, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2005) and externalizing (e.g., Beyers, Bates, Pettit, & Dodge, 2003) problems, empirical work has identified several neighborhood resources that protect parents and children from community- and family-level risk factors. Neighborhood cohesion, marked by a sense of trust and social ties among community members (Sampson, 2008), provides youth with socio-emotional resources outside of the home, including adults and peers to talk with, and support in times of distress. The availability, support, and involvement of positive role models in the community foster inclusion and belonging, and in turn, lead to better emotional, behavioral, and health outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). In addition, neighborhood cohesion mitigates the negative effects of neighborhood-level stressors, including exposure to violence (Kliewer et al., 2004) and economic deprivation (Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996; Odgers et al., 2009), on individual adjustment. Neighborhood cohesion also can buffer youth from family-level risks to optimal development. For example, neighborhood collective efficacy delayed sexual initiation among adolescents who experienced low levels of parental monitoring (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2005).

Considerably less is known about whether neighborhood cohesion protects against the negative consequences of discrimination, per se. Only one study, to our knowledge, has examined these associations, finding that the positive association between chronic discrimination and depression was reduced for African American young mothers who lived in more cohesive neighborhoods (Lewin et al., 2011). These findings lend support to the notion that neighborhood cohesion mitigates the impact of discrimination. However, whether neighborhood cohesion is protective for adolescent well-being is unknown, and it is unclear whether the function of cohesion varies according to where discrimination occurs. Youth who experience discrimination in their own neighborhood may be less adversely affected if the neighborhood is characterized by high cohesion. For one, they may be more likely to perceive the discriminatory event as aberrant, and therefore, less threatening. For another, support from community members may be more meaningful when they, too, are familiar with the source of the discrimination, or when the discrimination violates their collective identity. To advance understanding of neighborhood cohesion as a protective factor, we tested whether neighborhood cohesion moderated the links between adolescents’ discrimination experiences and internalizing/externalizing behaviors.

The Present Study

Drawing on an ecological framework, this study addressed two goals. Building on research on the implications of racial discrimination, and on adolescents’ growing involvement in extra-familial contexts, the first goal was to examine associations between discrimination experienced within and outside of youth’s neighborhoods and their externalizing and internalizing behaviors. On the basis of research and theory suggesting that experiencing stressors in proximal contexts may be especially damaging for youth, we expected that within-neighborhood discrimination would have more serious implications for youth’s adjustment than outside neighborhood experiences. Extending past research on the protective function of social supports, the second goal was to examine the moderating role of neighborhood cohesion for these associations. Here, we expected that neighborhood cohesion would provide supports for youth and mitigate the effects of discrimination for their adjustment, especially for within-neighborhood discrimination.

Given the implications of family and individual characteristics for discrimination experiences and adolescent adjustment, we included controls for youth gender, age, family socioeconomic status, and family structure. To understand the contributions of neighborhood discrimination and cohesion to adolescent adjustment independent of potentially adverse neighborhood conditions we also controlled for neighborhood-level poverty, residential stability and immigrant concentration in all models. Finally, to ensure that associations were not driven by the racial composition of youth’s neighborhoods, we also controlled for the percentage of African American residents.

Method

Study Design

This study uses two independent sources of data gathered by the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN), a study investigating the development of youth and families in the context of urban neighborhoods. Data at the youth and family levels are drawn from the third wave of the Longitudinal Cohort Study (PHDCN-LCS). Data at the neighborhood level are drawn from the Community Survey (PHDCN-CS) and the 1990 U.S. Census.

Longitudinal Cohort Survey

Participants were sampled by neighborhood using a multistage sampling strategy (for details on study design see Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). First, the city of Chicago was divided into 847 census tracts using 1990 U.S. Census data, and these tracts were assigned to one of 343 neighborhood clusters (NCs) that were ecologically meaningful and geographically compact. The NCs were then stratified into seven levels of race/ethnicity and three levels of socioeconomic status (high, medium, and low), resulting in 21 strata. Three strata did not contain any NCs (i.e., NCs classified as low SES, primarily white; high SES, primarily Latino; and high SES, primarily black and Latino). This stratification process resulted in a final representative sample of 80 NCs. Households within these NCs were randomly selected and screened for eligibility; those with children within 6 months of the target age or “cohort” (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18) were selected to participate, as were their primary caregivers. Of 8,034 eligible caregivers and their offspring, a final sample of 6,228 participated in the first wave of data collection.

There were three waves of data collection (1994–1997–1997–1999, and 2000–2001). At each wave, a trained data collector visited the family at home to interview the primary caregiver and observe the home environment. Informed consent was obtained from caregivers and youth prior to each interview. Questions covered the child’s development and family life. For the older cohorts, a separate interview was also conducted with the child. Interpreters were provided for non-English speakers. Participants received $5 – $20 per interview depending on their age and the wave of data collection.

This study draws on the 9- and 12-year-old cohorts (mean age at wave 3 = 15.24, SD = 1.56), as they were the only cohorts that reported on discrimination experiences. There were 587 African American youth in these two cohorts at wave one, and 461 by wave three (when questions about discrimination were asked). Attrition analyses revealed that youth who dropped out came from families with lower average income, t = 2.61, p < .01, and fewer family members, t = 2.14, p < .05, relative to those who remained in the study. Accordingly, household income and family size were controlled in all analyses.

Community Survey

The goal of this survey was to gather in-depth information about the NCs from residents who were not participants in the LCS. These data were collected between the years 1994–1995 and involved a three-stage sampling strategy. In the first step, city blocks were randomly selected from the 343 NCs. Second, households within blocks were randomly selected, and third, one adult respondent from each household was randomly chosen to complete the survey. A total of 8,782 respondents over the age of 18 provided information via mailed surveys on the structural characteristics and social processes of their neighborhood. Variables were aggregated to neighborhood-level averages.

Measures

All youth and family characteristics were drawn from wave three of the LCS. Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations (SDs), and frequencies for study variables.

| Variable | Percent of sample | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1: | ||

| Youth age | 15.24 (1.56) | |

| Gendera | 49.40 | |

| Parent education | ||

| Less than HS | 31.35 | |

| HS only | 15.67 | |

| More than HS | 45.83 | |

| Family income | 4.88 (2.69) | |

| Family size | 5.23 (2.31) | |

| Married biological parents | 20.79 | |

| Eternalizing | 9.04 (5.91) | |

| Internalizing | 10.06 (7.26) | |

| Discrimination within-neighborhood | 10.90 | |

| Discrimination outside-neighborhood | 27.43 | |

| Discrimination within- and outside-neighborhood | 6.20 | |

| Level 2: | ||

| Concentrated disadvantage | 2.17 (3.43) | |

| % African American residents | 70.30 (32.60) | |

| Residential stability | .31 (1.16) | |

| Immigrant concentration | −.40 (2.26) | |

| Neighborhood cohesion | 3.32 (.23) | |

Note.

Reference group for gender = male

Youth and Family Characteristics

Externalizing and internalizing problems

Adolescents reported on their externalizing (i.e., aggressive, hyperactive, noncompliant, and under-controlled) behaviors using items drawn from the Youth Self Report (YSR) externalizing scale (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1987). Using a 3-point scale (0 = not true to 2 = very or often true) adolescents indicated how well each of 19 items (e.g., “I destroy things belonging to others”) described them in the past 6 months (α = .81). Adolescents used items drawn from the YSR internalizing scale (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1987) to report on their internalizing (i.e., anxious, depressed, and over-controlled) behaviors. Using the same 3-point scale, adolescents indicated how well each of 21 items (e.g., “I feel worthless or inferior”) described their feelings or thoughts in the past 6 months (α = .86). Items in each scale were summed such that higher scores indicated more problems.

Racial discrimination experiences

Adolescents indicated (1 = yes) whether they had been “treated badly or differently because of their race, ethnicity, color,” first, when they were in their own neighborhood and second, when they were outside of their own neighborhood, in the past year.

Youth and family control variables

All analyses controlled for the following individual and family characteristics, measured at wave 3: Youth gender (1 = male), youth age, household per capita income (1 = less than $5,000 to 11 = more than $90,000; a score of 5 corresponds to $30,000 $39,000 per year), primary caregiver education, family size, and family structure (1 = does not live with both biological parents).

Neighborhood Characteristics

Neighborhood cohesion

Participants in the CS reported their agreement with five statements indicative of neighborhood cohesion: (1) People around here are willing to help their neighbors, (2) People in this neighborhood can be trusted, (3) This is a close-knit neighborhood, (4) People in this neighborhood generally don’t get along with each other (reverse scored), and (5) People in this neighborhood do not share the same values (reverse scored). Responses ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Responses were averaged (α = .75), such that higher scores indicated greater neighborhood cohesion.

Neighborhood control variables

Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of adolescents’ neighborhoods drawn from the 1990 U.S. Census were included as controls. Using principal components analysis, previous analysis of NC-level data identified three key dimensions of neighborhood level socioeconomic structure (Sampson et al., 1997). Concentrated poverty is defined by the percentage of families below the poverty line, the percentage of families receiving public assistance, the percentage of female-headed households, and the percentage of unemployed residents. Residential stability is measured by the continuity of residence and percentage of households that are occupied by owners. Immigrant concentration combines the percentage of Latino residents and percentage of foreign-born residents. We also controlled for the percentage of African American residents, given our interest in racial discrimination for African Americans.

Results

Analytic Strategy

We tested two-level multilevel models (MLM) to examine the associations among racial discrimination, neighborhood cohesion, and adolescent adjustment, using SAS Version 9.2. This approach extends multiple regression to account for dependencies in the data (i.e., correlations among youth in the same neighborhood). Youth-level data (externalizing and internalizing problems, discrimination, and individual and family controls) were modeled at Level 1, which captures differences among adolescents. Neighborhood-level data (neighborhood cohesion and neighborhood controls) were modeled at Level 2, which captures differences among neighborhoods. Youth came from a total of 52 different neighborhoods. All continuous predictor and control variables were centered at their grand means.

Of the 461 African American youth in cohorts 9 and 12 who participated at wave three of the study, 364 (79%) had complete data on the variables of interest. Missing data on constructs of interest ranged between 0 – 21%. To reduce potential bias from excluding participants with missing data, we performed multiple imputation using the Proc MI command in SAS version 9.2. Each data set was analyzed separately using the Proc Mixed command and then results were combined using Proc MI Analyze. Following new conventions of multiple imputation, we generated and analyzed 50 data sets. In line with Von Hippel (2007), the dependent variables were included in imputation models of the predictor variables but were not themselves imputed in order to minimize noise.

Experiences of Racial Discrimination

Eleven percent of youth experienced discrimination within their own neighborhood, and 27% experienced discrimination outside of their neighborhood, in the past year; very few (6%) experienced discrimination in both contexts (Table 1). To understand whether youth’s demographic characteristics helped to explain whether or where they had experienced discrimination, we conducted a series of mean comparisons between youth who did versus did not report discrimination (Table 2). Comparisons were conducted separately for discrimination that occurred outside and within their neighborhood. Youth who experienced discrimination outside of the neighborhood were older, on average, than those who did not, but there were no significant age differences between youth who did and did not experience within-neighborhood discrimination. Youth who experienced discrimination within their neighborhood and outside of their neighborhood had less educated parents than youth who did not. However, boys and girls did not differ in their experiences of discrimination in either context, and there were no significant differences in household income, mean family size, and family structure for youth who experienced discrimination in and outside of the neighborhood, relative to those who did not. Further, the mean levels of concentrated disadvantage, percentage of African American residents, residential stability, and immigrant concentration did not differ for youth who did and did not experience discrimination in either context. In sum, it did not appear that the adolescents who experienced discrimination, either within or outside their neighborhood, differed strongly from their peers in terms of background or neighborhood characteristics.

Table 2.

Mean-level differences in background characteristics associated with discrimination experienced in each context.

| Discrimination within-neighborhood | Discrimination outside-neighborhood | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % | |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||||

| Youth age | 15.21 (1.53) | 15.04 (1.61) | 15.10 (1.54) | 15.43 (1.52)* | ||||

| Gendera | 49.23 | 50.77 | 49.07 | 50.93 | ||||

| Parent education | ||||||||

| Less than HS | 30.27 | 40.00 | 30.37 | 33.96 | ||||

| HS | 15.71 | 15.38 | 15.65 | 15.72 | ||||

| More than HS | 47.32 | 33.85* | 49.13 | 39.62* | ||||

| Family income | 4.89 (2.59) | 4.59 (2.84) | 4.92 (2.62) | 4.69 (2.62) | ||||

| Family size | 5.21 (2.29) | 5.45 (2.51) | 5.29 (2.32) | 5.10 (2.30) | ||||

| Married biological parents | 19.92 | 27.69 | 20.56 | 21.38 | ||||

| Neighborhood characteristics | ||||||||

| Concentrated disadvantage | 2.21 (3.43) | 1.80 (3.46) | 2.26 (3.42) | 1.91 (3.48) | ||||

| % African American residents | 70.89 (32.47) | 65.58 (33.64) | 71.55 (32.01) | 67.02 (34.05) | ||||

| Residential stability | .32 (1.17) | .27 (1.17) | .30 (1.15) | .33 (1.20) | ||||

| Immigrant concentration | −.43 (2.24) | −.20 (2.45) | −.48 (2.18) | −.20 (2.46) | ||||

Note. Comparisons are between youth who did versus did not experience discrimination, within context of discrimination (within or outside neighborhood). T-tests are used to compare continuous variables and chi-square tests are used to compare categorical variables. Calculations are based on multiply imputed data.

Reference group for gender = male.

p<.10,

p < .05,

p < .01

To examine whether discrimination within and/or outside of the neighborhood were associated with youth’s externalizing and internalizing problems, we tested a MLM for each outcome. Models included indicators of having experienced discrimination within one’s neighborhood and having experienced discrimination outside one’s neighborhood; the reference group was no discrimination experienced at all. All MLM results are shown in Table 3. Findings revealed that, relative to youth who reported no discrimination experiences, those who experienced discrimination within their neighborhood had significantly higher externalizing problems, γ = 1.95, SE = 1.08, p < .05. However, youth who experienced discrimination outside their neighborhoods did not have elevated externalizing problems. Discrimination inside the neighborhood, γ = 4.21, SE = 1.22, p < .01, and discrimination outside the neighborhood, γ = 2.17, SE = 0.92, p < .01, were both associated with higher internalizing problems. A post-estimation z-test revealed that the difference between the coefficients for within- and outside-neighborhood discrimination in the model of internalizing problems was not statistically significant, z = 1.23, ns. Thus, racial discrimination was no more strongly associated with internalizing problems when it happened inside versus outside adolescents’ neighborhood of residence.

Table 3.

Multilevel model (MLM) coefficients for discrimination predicting externalizing and internalizing, moderated by neighborhood cohesion.

| Externalizing | Internalizing | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| γ (SE) | γ (SE) | |

| Level 1 Predictors | ||

| Intercept | 9.33 (.68)** | 10.79 (.84)** |

| Youth age | .74 (.21)** | .21 (.25) |

| Gender a | −.85 (.63) | − 3.42 (.77)** |

| Parent education | ||

| HS | .62 (.92) | − 1.18 (1.13) |

| More than HSb | −.94 (.75) | −.05 (.92) |

| Family income | −.18 (.14) | −.12 (.17) |

| Family size | .13 (.14) | .25 (.17) |

| Family structure (non-biological)c | −.10 (.83) | .25 (1.01) |

| Discrimination within-neighborhood | 1.95 (1.08)* | 4.21 (1.22)** |

| Discrimination outside-neighborhood | .71 (1.15) | 2.17 (.92)** |

| Level 2 Predictors | ||

| Concentrated disadvantage | .06 (.19) | .32 (.23) |

| Immigrant concentration | −.26 (.33) | −.25 (.40) |

| % African American residents | −.02 (.03) | −.02 (.04) |

| Residential stability | −.06 (.56) | .57 (.69) |

| Neighborhood cohesion | 2.69 (2.59) | 3.05 (3.19) |

| Cross-Level Interaction | ||

| Discrimination within-neighborhood X neighborhood cohesion | − 10.92 (5.08)* | − 7.79 (6.21) |

| Discrimination outside-neighborhood X neighborhood cohesion | 2.83 (3.20) | − 1.88 (3.97) |

Note.

Reference group for gender = Male

HS = High school; reference group is less than high school education

Reference group is married, biological family

p<.10,

p < .05,

p < .01

The Moderating Role of Neighborhood Cohesion

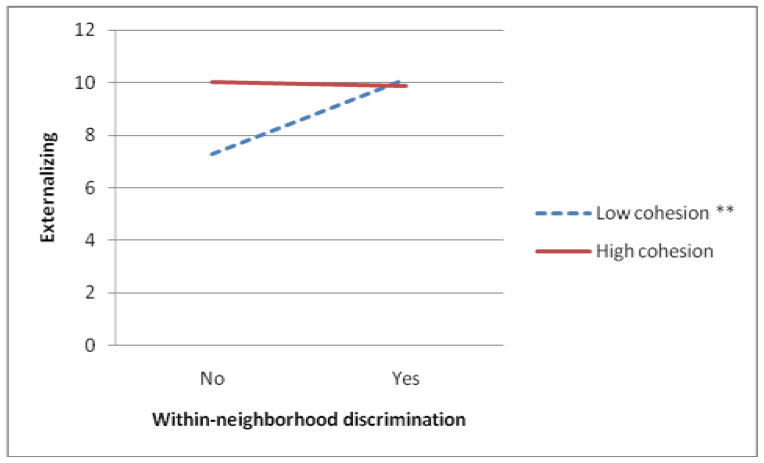

In a next step, we added two two-way interactions involving neighborhood cohesion and discrimination within and outside of the neighborhood to each model. As shown in table 3, there was no significant main effect of neighborhood cohesion for adolescents’ externalizing or internalizing behaviors. Neighborhood cohesion was a significant moderator of the link between within-neighborhood discrimination and adolescents’ externalizing problems, γ = −2.50, SE = 1.18, p < .05. However, neighborhood cohesion did not moderate the association between discrimination experienced outside the neighborhood and externalizing problems, γ = .58, SE = .74, ns, nor did it moderate associations between either type of discrimination experience and internalizing problems, γ = −1.71, SE = 1.45, ns, for within-neighborhood, and γ = −.47, SE = .90, ns, for outside neighborhood discrimination. Moderation was probed using simple slopes procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991). Specifically, we examined the association between the experience of within-neighborhood discrimination and externalizing problems at high (1 SD above the mean) versus low (1 SD below the mean) levels of neighborhood cohesion.

As illustrated by Figure 1, for youth who lived in neighborhoods with low cohesion, the association between discrimination in the neighborhood and externalizing was strong and positive, γ = 4.31, SE = 1.70, p < .01, d = .43. However, the association between discrimination in the neighborhood and externalizing was non-significant for youth living in neighborhoods characterized by high cohesion, γ = −.23, SE = 1.36, ns. Thus, strong neighborhood cohesion attenuated the link among youth between experiencing discrimination in one’s own neighborhood and having greater externalizing problems.

Figure 1.

Links between within-neighborhood discrimination and externalizing, moderated by neighborhood cohesion.

† p<.10, * p < .05, ** p < .01

Discussion

Growing research documents that experiences of racial discrimination negatively impact the adjustment of African American youth (e.g., Brody et al., 2006; Simons et al., 2006). The findings from this study are consistent with this body of evidence, and also extend it by examining whether the neighborhood context in which discrimination takes place has differential implications for urban adolescents’ adjustment. Further, we examined the potentially protective role of neighborhood cohesion, a factor that has been found to mitigate the adverse effects of other environmental stressors on youth (e.g., Aneshensel & Sucoff, 1996). In the following pages, findings are reviewed in greater detail, directing attention to the ways in which this study advances understanding of racial discrimination and neighborhood cohesion among African American youth in urban neighborhoods, and the sociocultural context of adolescent well-being, more generally.

Neighborhood Contexts for Discrimination and Links to Adolescent Adjustment

Findings related to the neighborhood context of discrimination yield new insights about discrimination experiences for African American youth. Overall, adolescents were more likely to experience discrimination outside of, rather than within, their neighborhoods. It may be the case that service personnel (e.g., storekeepers) or positions of authority (e.g., teachers, police officers) are more likely to be occupied by African American adults in African American youth’s own neighborhoods than in other neighborhoods. However, it is also possible that such positions are occupied by similar proportions of non-African Americans within and outside youth’s neighborhood, but in their own neighborhoods, adolescents are more familiar with these figures, and this familiarity may dampen the incidence of discrimination. Additionally, some experiences of discrimination may not have involved power differentials. For example, some youth may have experienced discrimination during interactions with same-aged peers. In sum, these findings confirmed our expectation that context matters for discrimination experiences, although further research is needed to shed light on why discrimination was more prevalent outside of youth’s own neighborhoods.

In contrast to Hunt et al. (2007), who found that African American adults who live in predominantly African American neighborhoods experience less discrimination than their peers who reside in neighborhoods where they are a racial-ethnic minority, we found no evidence among adolescents that discrimination experiences varied according to neighborhood racial composition. In our study, the mean proportion of African American residents in the home neighborhoods of youth who experienced discrimination in their neighborhood was, on average, 66% compared to 71% for youth who did not experience discrimination in their neighborhood. Further research is needed to explore the possibility that neighborhood racial composition affects the likelihood that African Americans experience discrimination differentially for adolescents and adults.

It was surprising that neighborhood concentrated poverty and immigrant concentration were not associated significantly with African American youths’ within-neighborhood discrimination experiences in light of what is known about the role of neighborhood social context for other social stressors (e.g., Sampson, 2008). It is essential that these analyses be replicated in other samples, first because the present sample represents only one city, and second, because more current neighborhood-level data are needed. Future studies on neighborhood-level variation in discrimination experiences might collect information on the proportion of time residents spend outside versus inside their neighborhood, and on the specific situations in which discrimination is encountered.

Our expectation that discrimination experienced within adolescents’ own neighborhoods would be related more strongly to their adjustment problems than discrimination experienced in outside-neighborhood contexts was only partially fulfilled. Discrimination that occurred within youth’s neighborhoods (but not outside) was associated with greater externalizing behaviors. However, there were no differential implications of within- versus outside- neighborhood discrimination for internalizing problems. According to Agnew (2001), stressors that threaten salient activities or identities are more likely than other stressors to lead to delinquent behavior; this may be one explanation for why youth who experienced discrimination in their neighborhoods (but not outside them) reported higher externalizing problems. By contrast, it appears that, regardless of where experiences occur, discrimination is associated with increased anxiety and distress. That may explain in part why there is more research documenting links between discrimination and internalizing problems (Ajrouch et al., 2010; Lewin et al., 2011; Prelow, Mosher, & Bowman, 2006; Simons et al., 2002) than externalizing problems (e.g., Brody et al., 2006; McCord & Ensminger, 2002; Simons et al., 2006).

Indeed, the pattern of past findings, together with the present results, suggests the possibility that internalizing is the predominant response in adolescents who encounter discrimination. According to Broman, Mavaddat, and Hsu (2000), African American adults’ typical responses to acts of interpersonal (as opposed to institutional) discrimination are feelings of futility and depression. For adolescents, externalizing may result only when conditions conspire to make the discrimination experience particularly difficult to cope with. One such condition may be when the discrimination threatens an adolescent’s emotional security, which might occur when it takes place in the adolescent’s neighborhood, an environment formerly perceived as trusting and accepting. Even then, though, this study’s results suggest that high neighborhood cohesion can stave off externalizing problems. Further research is needed to test the proposition that internalizing is the default reaction to discrimination and that externalizing emerges only in when the discrimination is particularly traumatizing. In addition, research is needed to explore the conditions and contexts in which discrimination is more likely to be viewed as especially harmful.

The Moderating Role of Neighborhood Cohesion

A second contribution of this study was to identify the role of neighborhood cohesion as protective for racial discrimination that occurs within the neighborhood context. Consistent with our expectation, the link between discrimination and externalizing was non-significant for youth living in highly cohesive neighborhoods. This finding suggests that close ties among neighbors may be more meaningful when discrimination is experienced within (versus outside) the neighborhood, and thus, may be a shared stressor.

On the other hand, cohesion did not mitigate the effect of neighborhood discrimination on internalizing problems. It is possible that living in a tight-knit community conferred benefits on youth who acted out but not those who were depressed or anxious in response to discrimination because behavioral problems were easier for community members to identify and intervene on. This possibility would be consistent with prior research showing limited evidence that social support buffers the impact of discrimination on psychological distress among adults (e.g., Ajrouch et al., 2010) and adolescents (e.g., Prelow et al., 2006). Indeed, with the exception of one study by Lewin and colleagues (2011), most prior evidence suggests that social support attenuates the association between adolescents’ discrimination experiences and externalizing problems (e.g., Simons et al., 2006). In contrast, it appears that protective factors specific to race, including racial identity and racial socialization, mitigate the link between discrimination and adolescents’ internalizing problems, perhaps because these factors diminish negative messages that threaten youths’ self-concepts.

Also in line with our expectations about the role of neighborhood cohesion, there was no evidence that cohesion mitigated the implications of discrimination experienced outside of youth’s neighborhood contexts. This finding suggests that support from neighbors may be less relevant when discrimination occurs in other places. Together, findings from this study highlight a need for more research on the contextual factors that shape adolescents’ experiences of stressors and supports.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

A primary strength of this study is its multilevel design. In particular, measures of the neighborhood were drawn from sources other than the adolescents who reported on discrimination and adjustment. Also, importantly, the adolescents actually were sampled by neighborhood. Both of these features are desirable for studies of individual development within neighborhood contexts (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). We were among the first to examine empirically where discrimination occurs and its links to two types of adjustment for African American adolescents. We considered youth’s neighborhoods as both a context for racial discrimination and a potentially protective factor. The links between within- and outside-neighborhood discrimination and adjustment problems remained significant, even after adjusting for a range of individual and neighborhood level characteristics.

Despite our reliance on some of the best data and methodology for understanding neighborhood processes and adolescent development, this study was not without limitations. First, cross-sectional data does not allow for causal inferences: Longitudinal data are needed to clarify the direction of the associations we uncovered. In addition, these results cannot be generalized beyond our sample of African American adolescents living in urban Chicago neighborhoods. Currently, research on the experiences of African American youth in non-urban settings is seriously limited. Because minority status may hold even stronger negative implications for youth in rural settings with limited racial diversity, it is important for future research to expand our understanding of these processes to different types of neighborhoods.

Our measure of discrimination was based on yes/no questions about discrimination. While this approach is not without precedent (e.g., Prelow, Danoff-Burg, Swenson, & Pulgiano, 2004), it limits the complexity of information collected. Also, as with all self-report measures, we cannot ensure that adolescents applied the same criteria to their perceptions of discriminatory experiences. Further, we did not capture the severity of youth’s experiences, which also matters for subsequent adjustment (e.g., Simons et al., 2001; 2006). Future research should account for both the severity and the context of discrimination to determine whether the implications of discrimination depend on the frequency of these experiences across different settings.

In conclusion, these findings carry important implications for theory and research on the impact of discrimination and the importance of neighborhoods for adolescent well-being. Theoretical models and empirical studies largely have overlooked the role of neighborhoods for urban adolescents, despite their growing involvement in settings outside of the home. Further, adolescents’ involvement in extra-familial social contexts may put them at heightened risk for racial discrimination. Greater knowledge of where these experiences are the most traumatizing, and what kinds of supports may mitigate the negative implications of discrimination across contexts will help researchers and policy-makers to address a major source of distress for urban minority youth, one that becomes increasingly prevalent and damaging across adolescent development. Findings from this study offer a first step towards developing interventions that may promote resilience in the face of racial discrimination across contexts.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01HD060719.

Footnotes

Research Interests:

Elizabeth Riina is a Research Scientist at the National Center for Children and Families, at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her doctorate in human development and family studies from Penn State University. Her research interests include socio-cultural influences on adolescent development.

Anne Martin is a Senior Research Scientist at the National Center for Children and Families at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her doctorate in public health from Columbia University. Her research interests include contextual influences on children and adolescents.

Margo Gardner is a Research Scientist at the National Center for Children and Families at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her doctorate in developmental psychology from Temple University. Her research focuses primarily on contextual influences on socioemotional development in adolescence and young adulthood.

Jeanne Brooks-Gunn is the Marx Professor and Co-Director of the National Center for Children and Families at Teachers College, Columbia University. She is interested in policy-relevant research on children and families, and she develops and evaluates interventions.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the youth self-report and profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Building on the foundation of General Strain Theory: Specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:319–361. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Experienced, vicarious, and anticipated strain: An exploratory study on physical victimization and delinquency. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19:603–632. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, Ismail A. Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: Does social support matter? Ethnicity and Health. 2010;15:417–434. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.484050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA. The neighborhood context of adolescent mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:293–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyers JM, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA. Neighborhood structure, parenting processes, and the development of youths’ externalizing behaviors: A multilevel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:35–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1023018502759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL, Mavaddat R, Hsu S. The experience and consequences of perceived racial discrimination: A study of African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34:844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Sexual initiation in early adolescence: The nexus of parental and community control. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:758–78. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Price-Spratlen T. Through the eyes of children: An ethnographic perspective on neighborhoods and child development. In: Masten AS, editor. Cultural processes in child development: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Vol. 29. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1999. pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Coleman AP, Novak JD. Brief report: Initial psychometric properties of everyday discrimination scale in black adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Burk-Braxton C, Swenson LP, Tevendale HD, Hardesty JL. Race and gender influences on adjustment in early adolescence: Investigation of an integrative model. Child Development. 2002;73:1573–1592. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich JJ, Graeven DB. Reciprocal self-disclosure in a dyad. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1971;7:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR. The continuing significance of race: Anti-black discrimination in public places. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest R, Kearns A. Social cohesion, social capital, and the neighbourhood. Urban Studies. 2001;38:2125–2143. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia H, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody GH. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harger S. Processes underlying adolescent self-concept formation. In: Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullota TP, editors. From childhood to adolescence: A transitional period? Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. pp. 205–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MO, Wise LA, Jipguep M, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. Neighborhood racial composition and perceptions of racial discrimination: Evidence from the black women’s health study. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70:272–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Cunningham JN, Diehl R, Parrish KA, Walker JM, Atiyeh C, Mejia R. Violence exposure and adjustment in inner-city youth: Child and caregiver emotion regulation skill, caregiver-child relationship quality, and neighborhood cohesion as protective factors. Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:477–487. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin A, Mitchell SJ, Rasmussen A, Sanders-Phillips K, Joseph JG. Do human and social capital protect young African American mothers from depression associated with ethnic discrimination and violence exposure? Journal of Black Psychology. 2011;37:286–310. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DW, Chavis DM. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14:6–23. [Google Scholar]

- McCord J, Ensminger ME. Racial discrimination and violence: A longitudinal perspective. In: Hawkins D, editor. Violent crime: Assessing race and ethnic differences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Tach LM, Sampson RJ, Taylor A, Matthews CL, Caspi A. The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on British children growing up in deprivation: A developmental analysis. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:942–957. doi: 10.1037/a0016162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescence and adulthood: A review and integration. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Danoff-Burg S, Swenson RR, Pulgiano D. The impact of ecological and perceived discrimination on the psychological adjustment of African American and European American youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32:375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Mosher CE, Bowman MA. Perceived racial discrimination, social support, and psychological adjustment among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology. 2006;32:442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–792. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. New Brunswick; NJ: 2008. pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: Testing social- disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94:774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Sellers RM. Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chen Y, Stewart EA, Brody GH. Incidents of discrimination and risk for delinquency: A longitudinal test of strain theory with an African American sample. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:827–854. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLyod V, Lin KH, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:371–393. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummond H, Stewart E, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel PT. Regression with missing Ys: An improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology. 2007;37:83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earles FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11- year olds. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:554–563. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]