Abstract

Background

Premature infants fed formula are more likely to develop necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) than if fed breast milk, but the mechanisms of intestinal necrosis in NEC and protection by breast milk are unknown. We hypothesized that after lipase digestion, formula, but not fresh breast milk, contains levels of unbound free fatty acids (FFAs) that are cytotoxic to intestinal cells.

Methods

We digested multiple term and preterm infant formulas or human milk with pancreatic lipase, proteases (trypsin and chymotrypsin), lipase + proteases, or luminal fluid from a rat small intestine and tested FFA levels and cytotoxicity in vitro on intestinal epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and neutrophils.

Results

Lipase digestion of formula, but not milk, caused significant death of neutrophils (ranging from 47–99% with formulas vs. 6% with milk) with similar results in endothelial and epithelial cells. FFAs were significantly elevated in digested formula versus milk and death from formula was significantly decreased with lipase inhibitor pretreatment, or treatments to bind FFAs. Protease digestion significantly increased FFA binding capacity of formula and milk but only enough to decrease cytotoxicity from milk.

Conclusion

FFA-induced cytotoxicity may contribute to the pathogenesis of NEC.

Keywords: free fatty acids, shock, lipase, cytotoxicity

Background

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is currently the leading cause of death from gastrointestinal disease in premature infants (1). It is characterized by abdominal distension, hemorrhage and necrosis of tissue within the intestine, peritonitis following intestinal perforation, and a rapid progression from initial discomfort to death (1).

Its cause is unknown, but NEC is rarely seen before oral feedings are initiated (2). Formula-fed premature infants have a greater risk of developing NEC than those fed with breast milk only (3), but the mechanism whereby breast milk protects from NEC is not completely understood (4). Current theories suggest that gut bacterial colonization and inflammation may play a role, but do not include a mechanism for the intestinal necrosis.

A mechanism that has received little to no attention in the pathophysiology of NEC is direct cytotoxicity of luminal content on intestinal tissue. We have observed that homogenates of digested food collected from the intestinal lumen of healthy rats, but not undigested food, are cytotoxic (5). This cytotoxicity results in intestinal hemorrhagic necrosis under ischemic conditions (6) that is similar to the intestinal hemorrhagic necrosis seen in NEC in infants. The cytotoxicity is likely due to the creation and transport of unbound, non-esterified (i.e. “free”) fatty acids (FFAs), formed during the digestion process, into the intestinal wall (6). A study in 1990 found antibacterial and antiviral activity, attributed to FFAs, in gastric aspirates of formula fed infants (7), suggesting digested formula could also damage intestinal tissue under ischemic or similar conditions.

Intestinal ischemia is known to cause a failure of the intestinal mucosal barrier, resulting in increased intestinal permeability (8). This allows transport of bacteria (9) and other molecules from the intestinal lumen into the intestinal wall (10). Eventually, multiple organ failure and death from shock can result. Increased intestinal permeability also occurs in premature infants (11) and remains high for extended periods in those premature infants that are fed infant formula as opposed to breast milk (12). Increased intestinal permeability may represent a common causal factor for hemorrhagic necrosis in NEC as well as intestinal ischemia.

Given that breast milk lowers risk of NEC, if intestinal damage in NEC is caused to some degree by entry of cytotoxic FFAs into the intestinal wall, then there should be a measurable difference in the cytotoxicity of digested fresh breast milk compared to digested formula. We therefore tested the cytotoxicity of breast milk and several term and pre-term infant formulas after digestion by selected pancreatic-derived digestive enzymes.

Our results indicate that numerous digested formulas are cytotoxic, while digested fresh breast milk is not. We show that cytotoxicity is due to the detergent action of high concentrations of FFAs, a mechanism for cell death that is independent of cell type.

Methods

Human Milk Collection and Handling of Milk and Formula

The Institutional Review Board and the Animal Subjects Committee of the University of California, San Diego, reviewed and approved all human and animal protocols, respectively. Human milk was obtained with informed consent from healthy volunteer mothers (N=12) via breast pump. A full expression was collected to mix fore- and hind-milk. Since breast milk stored at temperatures of −20 °C or greater can become cytotoxic due to formation of FFAs by milk lipases (13), we used fresh breast milk collected in the morning rather than a mixture of breast milks collected over 24 hours. The milk was kept at 4°C from the time of expression until it could be aliquoted (within 2 hours of expression) for immediate use or storage (−80 °C).

Unless otherwise noted, we used the full-term infant formula, Enfamil Infant (Mead Johnson & Company, LLC, Glenview, IL) reconstituted with water from a concentrated liquid form. Some cytotoxicity measurements were repeated using two additional powdered full-term formulas (Similac Advance and Similac Soy, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), four pre-term infant formulas used in hospitals (Enfamil Premature 20 and 24 kcal/oz formulas and Similac Special Care 20 and 24 kcal/oz formulas), and two pre-term post-discharge infant formulas (Enfamil EnfaCare 22 kcal/oz and Similac Expert Care NeoSure 22 kcal/oz).

Cytotoxicity Studies

We assayed for cytotoxicity using three cell types found in the intestine obtained from three different species: human neutrophils, primary bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs; a gift from Dr. Shu Chien, UCSD), and primary rat small intestinal epithelial cells (IECs; from ATCC; Manassas, VA). Neutrophils, isolated as previously described (5) from blood drawn from healthy donors, were logistically convenient for analysis of fresh breast milk and were used for most experiments, though some fresh milk (N=3) was also assayed using endothelial cells. The stored milk of all 12 mothers was tested on the same day on the epithelial cells (storage times at −80 °C varied from 26 to 236 days (Mean ± SD: 110 ± 62 days)).

Sample Preparation

We digested human milk or formula with PBS as control, porcine pancreatic lipase (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), bovine trypsin and chymotrypsin (proteases) (Sigma-Aldrich), all three enzymes in combination (lipase+proteases), or luminal fluid from the rat small intestine obtained after euthanasia (120 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital) of a male, Wistar rat. The exterior of the rat small intestine was rinsed in saline and its contents flushed out with 40 ml of saline. The luminal effluent (in 40 ml saline) was immediately homogenized, centrifuged (16000g, 20 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant aliquoted and stored (−80 °C) until use. At this dilution, luminal fluid is not cytotoxic on its own, but it can generate cytotoxicity if food is present as substrate for its enzymes (5).

Formula or human milk was incubated for 2 h (37°C) (similar to the transit time through an infant small intestine) after mixing 4:1 (v:v) with buffer or enzymes (1:1 in the case of luminal fluid). Final concentration of enzymes was 1 mg/ml for studies on neutrophils and 0.1 mg/ml for studies on endothelial and epithelial cells. These concentrations bracket and are on the order of concentrations in the intestinal lumen of human infants (14). Enzymes in buffer alone, or enzymes plus milk or formula but no digestion time, were the controls for neutrophil and cell culture studies, respectively. Since fat particulates interfere with quantification by flow cytometry, after digestion milk and formula samples for neutrophil cytotoxicity studies were centrifuged (16000g, 20 min, 4°C) to obtain the supernatant under the solid fat layer. These skimmed samples were then incubated with neutrophils. No skimming was required for cytotoxicity experiments on endothelial or epithelial cell cultures as samples could be aspirated without disturbing cells.

Neutrophil Cytotoxicity Assay

Neutrophils were incubated 1:1 with sample (106 cells/ml final, 1 h, room temperature), before adding the fluorescent life/death indicator propidium iodide (PI; 1 μM final; Sigma) and immediate reading in a flow cytometer. PI positive and negative cells were gated from dot plots as previously described (5), excluding particulates from the milk or formula samples, and cell death reported as the percentage of total cells that were PI positive. A sample was deemed “cytotoxic” if it caused more than 15% cell death measured in this fashion.

Endothelial and Epithelial Cell Cytotoxicity Assays

BAECs or IECs were grown in 96 well cell-culture treated plates and allowed to reach confluency overnight. Immediately after growth media aspiration, cells cultures were incubated with 80 μl of sample per well in triplicate for 5 min at room temperature. Following treatment, cells were washed twice with complete growth media and then incubated with 10 μg/ml PI for 2 min. Treatment with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 seconds immediately prior to the addition of PI served as a positive control for total (100%) cell death. Negative controls were untreated and stained for PI. After PI treatment, PI was rinsed and cultures were kept in their respective complete media for immediate live cell imaging.

Brightfield and fluorescent images were acquired in three fields per well and the number of PI positive (i.e. dead) cells averaged over each well for formula or over each donor for milk. Completely confluent cell areas were used to quantify cell death. Cell death was normalized to a percentage by the average number of PI positive cells detected after treatment with Triton X-100. A given sample was deemed “cytotoxic” if it caused more than 5% cell death measured in this fashion.

Fatty Acid Interventions and Quantification

FFAs in the body are usually found bound to proteins such as albumin and specific fatty acid binding proteins. In this study, we refer to total FFA concentration as the sum of bound and unbound FFA concentrations.

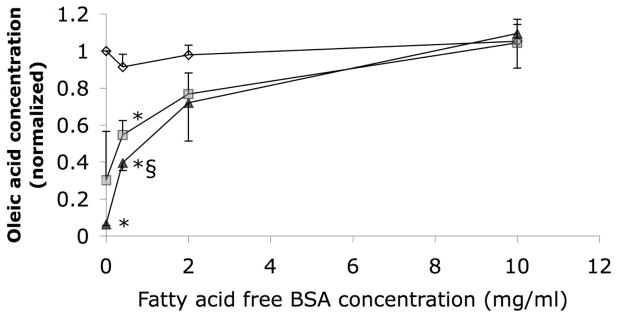

Total FFA concentration was determined in a 96-well plate using the Free Fatty Acids Half-Micro Test kit (Roche Applied Sciences; Indianapolis, IN). All samples were pre-diluted 10-fold to bring concentrations within the linear range of the assay (<1 mM), with reported values corrected to the original concentrations. We determined bound FFA concentrations by repeating the measure after filtration through 3–5 glass fiber pre-filters (Pall-Gellman; Port Washington, NY), which remove unbound, but not bound FFAs (Figure 1). All samples contained less than 0.5 mM FFA after dilution, and were therefore within the capacity of 5 filters to remove all unbound free fatty acids (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Oleic acid preparations (~0.5 mM, 0.9% ethanol, 10 mM PBS final) in 0–10 mg/ml BSA (binds FFAs), before filtration (diamonds) or after 3 (squares) or 5 (triangles) serial filtrations of 900 μl through glass fiber filters (N=3, normalized to the oleic concentration without BSA before filtering). FFA quantification is unaffected by presence of BSA before filtration. After 5 serial filtrations, in the presence of 10 mg/ml BSA, the FFA concentration was unchanged. In the absence of the fatty acid binding protein the glass fiber filtration removed essentially all of the FFAs. The interaction in the two-factor ANOVAs (filtration and BSA concentration) was significant (P<0.05, ηp2=0.81); P<0.01 considered significant for pair-wise comparisons. * less oleic acid versus before filtration (P<0.004). § more oleic acid versus without BSA (P<0.01; 5-filtered 2 and 10 mg/ml solutions approached significance, P=0.033 and P=0.011, respectively).

To determine the role of FFAs in formula cytotoxicity, formula samples were treated with orlistat (0.25 mg/ml final; Sigma) to inhibit lipase activity, with fatty acid-free BSA (20 mg/ml final; Sigma) to bind FFAs, or filtered through glass fiber filters to remove unbound FFAs.

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed in Excel and SPSS. Single or multi-factor ANOVA or mixed ANOVA (MANOVA) was completed for experiments with multiple groups followed by Bonferroni correction for pair-wise t-test comparisons.

Results

Cytotoxicity of digested formula vs. fresh breast milk

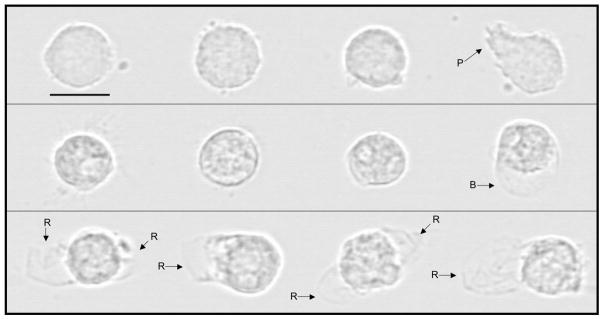

Our first objective was to determine if digestion would cause either formula or breast milk to become cytotoxic. Though there was some variability, all nine formulas digested with lipase (with or without protease) and skimmed were highly cytotoxic, as measured by human neutrophil death after 1-hour (Table 1). In contrast, identically treated fresh human milk was not cytotoxic, even using the stronger lipase concentration (1 mg/ml). The enzyme-only controls: lipase alone, or lipase and proteases together, on neutrophils for one hour caused no appreciable cell death (9.1±6.5 and 9.8±6.3 % death, respectively, vs. 10.0±6.9 % death after 1 hour of PBS alone). Similar to neutrophils exposed to other biologic solutions with high concentrations of FFAs (5, 6), neutrophils exposed to digested formula and milk show dramatic perturbations of the cell membranes (i.e. large blebs) (Figure 2). While blebs were rare in the milk group, nearly every cell in the formula group had evidence of a ruptured bleb. We have seen previously that rupturing of a bleb reduces the apparent size of the cell back down to approximately control levels as measured by flow cytotometry, and coincides with the entry of PI into the cell (i.e. cell death) through the opening in the plasma membrane (5).

Table 1.

| with PBS | with Protease | with Lipase | with Lipase + Protease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Human Breast Milk | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 1.5 ± 1.2§ | 6.2 ± 7.4 | 7.4 ± 12.3 |

| Enfamil Infant | 10.1 ± 7.3 | 5.5 ± 8.6§ | 60.0 ± 15.6*‡ | 85.9 ± 11.6*‡ |

| Similac Advance | 8.6 ± 7.3 | 5.8 ± 7.4 | 93.4 ± 3.3*‡ | 94.3 ± 4.0*‡ |

| Similac Soy | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 4.1 ± 2.0 | 70.8 ± 13.5*‡ | 77.8 ± 13.0*‡ |

| Enfamil Premature 20 kcal/oz | 9.8 ± 4.9 | 2.9 ± 1.1§ | 95.0 ± 3.1*‡ | 25.0 ± 7.9*§‡ |

| Enfamil EnfaCare 22 kcal/oz | 11.6 ± 2.6‡ | 3.7 ± 1.2§ | 46.7 ± 10.1*‡ | 43.7 ± 9.1*‡ |

| Enfamil Premature 24 kcal/oz | 13.4 ± 3.2 | 5.9 ± 1.2§ | 96.8 ± 1.0*‡ | 94.0 ± 1.9*‡ |

| Similac Special Care 20 kcal/oz | 12.6 ± 3.1 | 5.3 ± 1.7§ | 97.0 ± 0.4*‡ | 67.0 ± 11.8*§‡ |

| Similac Expert Care NeoSure 22 kcal/oz | 16.5 ± 5.6 | 4.9 ± 0.9§ | 90.7 ± 1.9*‡ | 65.1 ± 8.8*§‡ |

| Similac Special Care 24 kcal/oz | 13.2 ± 2.9‡ | 9.3 ± 1.4 | 98.9 ± 0.3*‡ | 96.7 ± 0.9*‡ |

% Mean ± SD

Samples defatted after digestion (2 hrs, 37 °C). Enzyme concentrations: 1 mg/ml. N=12 breast milk donors, N=11, 5, 5, 5, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4 independent replicates with formulas (in order listed). The interaction in the two-factor MANOVA (milk versus each formula – between subjects; digestion category – within subjects) was significant (P<0.05; ηp2=0.92).

more cell death vs. without lipase (P<0.007). P<0.025 considered significant.

less cell death vs. without protease (P<0.02). P<0.025 considered significant.

more cell death vs. breast milk (P<0.005); note in PBS column all formulas except Similac Advance and Similac Soy had P<0.02 (but P<0.005 was cut-off for significance by Bonferroni test due to number of comparisons).

Figure 2.

Representative images of human neutrophils exposed for 60 min, prior to glutaraldehyde fixation, to (top row) lipase (as control), (middle row) human milk (from −80 °C storage) digested with lipase, or (bottom row) infant formula (Enfamil Infant) digested with lipase. Cells exposed to high levels of FFAs form blebs – hemispherical balloon-like projections of the cell membrane away from the underlying cytoskeleton – pressurized by the slight osmotic gradient between a cell and its surroundings (present even in solutions of physiologic osmolarity). Eventually these blebs rupture, killing the cells, and allowing entry of the life/death indicator, PI. Of the 12 cells we observed under the microscope in the Milk + Lipase group, only one showed a bleb (included here to show the appearance of a bleb prior to rupture). All Formula + Lipase blebs had already ruptured, as shown by loss of bleb spherical shape. P = pseudopod, B = bleb, R = ruptured bleb. Bar = 10 μm (800x).

We then determined whether these phenomena were dependent on cell-type or species and whether the pattern of response would remain the same if samples were not skimmed. Short-term (5 min) incubation of lipase-digested whole formula, but not lipase-digested whole human milk, with BAECs and IECs also led to high levels of cytotoxicity (Table 2), despite a 10-fold lower concentration of applied digestive enzymes (0.1 mg/ml). The short incubation time also supports a necrotic, rather than apoptotic, mechanism. Interestingly, even control (PBS-digested) formula caused more cell death than breast milk in all three cell types, though this increase was only significant for two of the formulas (Table 1).

Table 2.

Bovine aortic endothelial cell (BAEC) and rat intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) deatha after 5 min exposureb

| Formula with PBS | Milk with PBS | Formula with Lipase | Milk with Lipase | Formula with Protease & Lipase | Milk with Protease & Lipase | PBS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| No digestion (BAEC)c | 3.2 ± 3.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 7.2 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 |

| 2 hr digestion (BAEC) | 7.0 ± 13.0 | 3.1 ± 3.0 | 38.1 ± 20.9* | 3.6 ± 3.7§ | 38.7 ± 19.6* | 1.1 ± 0.6§ | |

|

| |||||||

| No digestion (IEC)d | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| 2 hr digestion (IEC) | 2.7 ± 4.0 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 34.4 ± 8.2** | 3.3 ± 2.9‡ | 34.6 ± 11.7** | 3.8 ± 2.9**‡ | |

| Formula with Luminal Fluid | Milk with Luminal Fluid | PBS with Luminal Fluid | PBS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| No digestion (IEC)e | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 4.2 | 1.5 ± 0.5 |

| 2 hr digestion (IEC) | 67.7 ± 13.5† | 3.4 ± 1.8^ | 2.4 ± 1.0^ | |

% Mean ± SD

No defatting after digestion (0 or 2 hrs, 37 °C). Purified enzyme concentrations: 0.1 mg/ml. Cell death normalized by average number of PI positive cells/mm2 with Triton X-100 (1085±104, 809±123, and 510±52 cells/mm2 for BAECs, IEC (purified enzymes), and IEC (luminal fluid), respectively).

N for BAEC study = 16 wells for formula groups, 3 donors of fresh breast milk. Performed three-factor MANOVA (substrate – between subjects, digestion category – within subjects, and digestion time – within subjects). The three-way interaction was significant (P<0.05; ηp2=0.24).

N for IEC study using purified enzymes = 11 wells for formula groups, 12 donors of breast milk (stored −80 °C). Performed three-factor MANOVA (substrate – between subjects, digestion category – within subjects, and digestion time – within subjects). The three-way interaction was significant (P<0.05; ηp2=0.75).

N for IEC study using luminal fluid = 5 wells for formula or PBS with luminal fluid, 5 donors of breast milk (stored −80 °C). The interaction in the two-factor MANOVA (substrate – between subjects, and digestion time– within subjects) was significant (P<0.05; ηp2=0.94).

P<2×10−6 versus no digestion

P<8×10−5 versus equivalent formula group.

P<0.002 versus no digestion

P<6×10−6 versus equivalent formula group.

P<5×10−4 versus no digestion

P<4×10−4 versus formula group.

P<0.017 considered significant for all comparisons.

In order to better match the digestive enzyme profile present in the intestine, we tested whether formula or breast milk digested with endogenous enzymes from the lumen of the rat intestine would be cytotoxic to rat IECs. We again found that formula, but not breast milk, digested with luminal fluid was cytotoxic (Table 2).

When examining the effects of protease digestion on formula and breast milk, we observed that addition of the proteases, trypsin and chymotrypsin, to breast milk significantly reduced the already small amount of cell death in the control (Table 1). Many of the formulas also demonstrated a lower cytotoxicity than basal (control) levels if digested by protease. If combined with lipase digestion, protease digestion also significantly decreased the cytotoxicity of some formulas (Table 1), though it significantly increased it with Enfamil Infant formula (P<0.0005). Formula digested with proteases but without lipase remained non-cytotoxic.

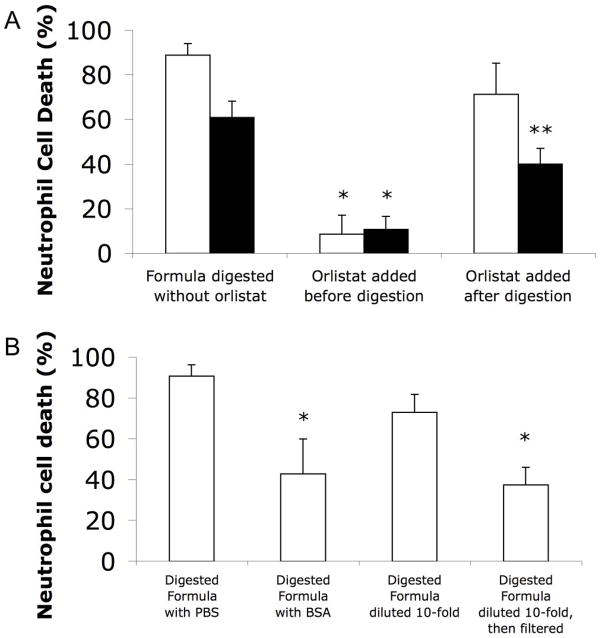

FFA Cytotoxic Mechanism

Lipase-digested formula cytotoxicity was only prevented if a lipase inhibitor, orlistat, was added at the beginning of the digestion period, confirming that lipase activity during digestion is the key requirement for cell death to occur (Figure 3A). Filtering cytotoxic digested formula with glass fiber filters, which bind and remove FFAs (Figure 1), significantly reduced cytotoxicity (Figure 3B). Likewise, addition of fatty acid-free BSA, a protein capable of binding FFAs, immediately before adding to cells significantly reduced cell death from digested formula (Figure 3B), suggesting that cell death is a consequence of the presence of unbound FFAs.

Figure 3.

Cell death (neutrophil) with and without interventions against FFA derived cytotoxicity from digested, then skimmed, formula. (A) Death caused by protease + lipase (white bars) or luminal fluid (black bars) digested formula without or with 0.25 mg/ml orlistat added at the beginning or the end of digestion. Formula, lipase, or luminal fluid alone did not cause cell death (not shown). Single factor ANOVAs (separate for each digestion type) were significant (both P<0.05; ηp2=0.97 for protease+lipase digestion; ηp2=0.96 for luminal fluid digestion); P<0.017 considered significant for pair-wise comparisons. * P<0.0023 less death vs. without orlistat. ** more death (P<0.013) than if orlistat added before digestion, but less death (P<0.0005) than without orlistat (reflecting the extra digestion that the group without orlistat gets during the 1 h incubation with cells). N=4. (B) Death caused by protease and lipase digested formula mixed 9:1 with either PBS or 200 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA to bind unbound FFAs, or with and without filtering through five glass fiber filters (after 10-fold dilution to bring fatty acid concentration down to a level where this degree of filtering could be effective). P<0.05 considered significant. * significantly (P<8×10−5) reduced cell death with BSA addition or filtering (N=8).

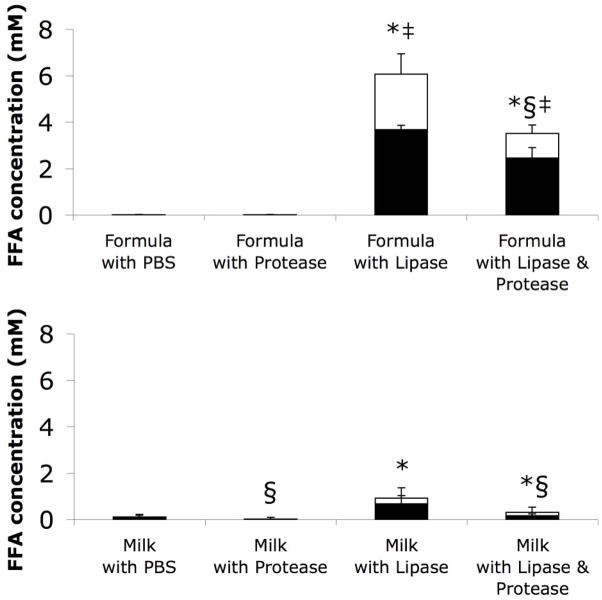

To confirm differences in the concentration of FFAs in cytotoxic versus non-cytotoxic samples, we measured total, bound, and, by subtraction, unbound FFA concentrations in aliquots of the same skimmed solutions tested for cytotoxicity on human neutrophils (Table 1 Breast Milk and Enfamil Infant), stored at −80 °C until testing (Figure 4). We detected little to no FFAs in fresh milk or formula incubated with PBS or proteases. Lipase digestion increased the total FFAs in both fresh breast milk and formula, but to significantly higher levels in formula. Moreover, the amounts of FFAs that were unbound in fresh milk digested with lipase or with lipase and protease were significantly less than in the lipase or lipase and protease digested formula. Interestingly protease digestion decreased the total FFA levels in all cases (except for formula with PBS which had no FFAs to reduce). Overall, unbound FFA concentration correlated with neutrophil cytotoxicity (correlation coefficient = 0.766).

Figure 4.

Total (full columns) and bound (black portion of columns) FFA concentrations in (top) formula or (bottom) milk after digestion and subsequent skimming (i.e. aliquots of the same solutions tested for cytotoxicity in Figure 1, frozen at −80 °C until FFA concentration analysis). The differences between the total and bound FFAs (white portion of columns) represent the concentrations of unbound FFAs. Significances shown in the figure refer only to total FFA levels. The interactions in the two-factor MANOVAs (food source – between subjects; digestion type – within subjects) for total and unbound FFA concentrations were significant (both P<0.05, ηp2=0.95 for total FFAs, ηp2=0.79 for unbound FFAs); P<0.017 considered significant for pair-wise comparisons. * P<6×10−4 in total FFA with versus without lipase digestion. ‡ P<3×10−4 in total FFA in formula group versus equivalent milk group. § significant (P<0.009) decrease in total FFA with protease digestion. N=12 for milk and 5 for formula. Significant differences in unbound FFAs were identical to those of total FFAs, with the following exceptions: unbound FFAs in milk digested with lipase and protease were not quite significantly higher than if digested with protease alone (P=0.019); unbound FFAs were not significantly reduced with protease digestion (P=0.035 for formula with lipase and protease versus with lipase only).

Pilot studies using samples that were not skimmed suggest that the FFA concentrations in the lipase-digested formula may be more than an order of magnitude higher than in the skimmed samples in Figure 4. However, the degree of dilution required to make samples (containing fat globules) readable by a plate reader greatly reduced the precision of the measurements, and thus was not studied here.

Protection by Proteases

We hypothesized that protease digestion of breast milk and formula may provide its protection from FFA-induced necrosis by increasing the overall number of protein/fatty acid binding sites (e.g. by exposing hydrophobic cores of globular proteins). Accordingly we compared the ability of whole human milk (stored at −80 °C), protease-digested whole human milk, whole formula (Enfamil Infant), and protease-digested whole formula to protect IECs from otherwise cytotoxic concentrations of the FFA, oleic acid, added exogenously at the end of digestion and immediately before addition to cells (Figure 5). We observed a significant difference in the level of protection between milk and formula with 35 mM oleic acid. However, prior protease digestion of either milk or formula significantly reduced the amount of cell death caused by exogenous oleic acid. This suggests that the FFA binding capacity of both fluids increased with addition of protease, though our other results suggest this was only sufficient to decrease cytotoxicity from breast milk, not lipase-digested Enfamil Infant formula (though other formulas may receive more benefit from protease digestion).

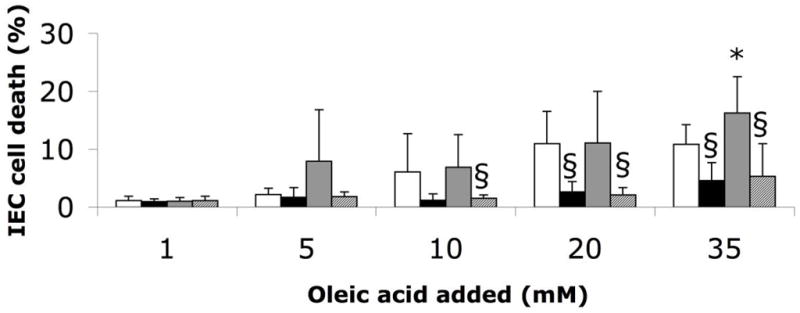

Figure 5.

IEC death caused by whole milk or formula (stored at −80 °C) digested for 2 hours at 37 °C (4:1) with PBS or 0.5 mg/ml trypsin and chymotrypsin (each 0.1 mg/ml final concentration) (milk: white bar, formula: grey bar, milk + protease: black bar, formula + protease: hatched bar), and after addition of exogenous oleic acid in varying concentrations. The results reveal the concentrations of exogenous oleic acid at which cytotoxicity arise, i.e. the points at which FFA binding capacity is exhausted. The two-factor MANOVAs (food source – between subjects; digestion type – within subjects) yielded a significant main effect of digestion type at the 5, 10, 20, and 35 mM oleic acid concentrations (P<0.05, ηp2=0.52 for 5 mM, ηp2=0.40 for 10 mM, ηp2=0.70 for 20 mM, ηp2=0.76 for 35 mM). There was also a significant interaction at 5 mM (P<0.05, ηp2=0.48); P<0.025 considered significant for pair-wise comparisons. * P<0.025 versus milk; § P<0.008 versus without protease. N=12 wells for formula group, 6 wells for Formula+Protease group, and 9 donors of breast milk. Milk with versus without protease at 10 mM oleic acid approached significance (P=0.06) as did Milk versus Formula and Formula versus Formula+Protease at 5 mM oleic acid (P=0.05 and P=0.04, respectively).

Discussion

Cell death after exposure to digested formula was rapid, under 5 min in some cases, and involved a physical destruction of cell membranes as indicated by large bleb formations and ruptures. Cell death occurred regardless of cell type and species of origin and depended on the formation and presence of unbound FFAs. Collectively this evidence suggests that the cell death is from the detergent action of FFAs directly on the cell membranes. Thus, this is a different type of damage mechanism than those considered in the intestine that depend on pathogens or specific cell surface proteins.

Though cell death through this mechanism is not dependent on bacteria, bacteria may further increase the concentration of FFAs, especially in the colon, as undigested carbohydrates that reach the colon are metabolized by bacteria into short chain FFAs (15). These short chain fatty acids are released into the intestinal lumen and, in low concentrations, they serve as food for the intestine and help reduce intestinal permeability (15). However in high concentrations, short chain fatty acids could increase the cytotoxicity of luminal fluid even further and have been shown in a quail model to cause NEC-like morphological changes in the colon (15, 16).

In the current study, neutrophils were chosen as one of our cell types for practical reasons. However, in addition to the lysosomal catabolic enzymes and other inflammatory mediators that would be released from nearly every human cell type undergoing necrosis, necrosis of neutrophils would result in uncontrolled release of their many bactericidal mediators. If this occurs in the intestine, it could enhance the damage to intestinal tissue.

Formula is designed to contain approximately the same overall fat content as breast milk, yet every digested formula we tested was more cytotoxic than breast milk and cytotoxicity appears due to increased FFA levels. One possible explanation could be breast milk deactivates pancreatic lipase and/or formula activates it. Another possibility is that the composition of fats, or form of lipid vesicular packaging, in breast milk may be less susceptible to lipase digestion. For example, fat globule diameter is at least 6-fold greater in milk than formula (17). As this would greatly decrease the overall surface to volume ratio of the fat, the reaction kinetics, and thus the rate of FFA generation in milk, may be greatly reduced (18). FFAs may also be elevated in the intestines of formula-fed infants due to poor absorption of long chain saturated FFAs (19). For example, whereas in human milk the long chain fatty acid palmitic acid is primarily at the sn-2 position and is readily absorbed as a monoglyceride by intestinal cells, palmitic acid is primarily located at the sn-1, 3 positions of triglycerides in most formulas and is thus de-esterified by pancreatic lipase, which preferentially cleaves at those positions (19). Poorly absorbed free palmitic acid could then accumulate in the intestinal lumen.

The current findings differ from those in the study with gastric aspirates (7), which reported comparable antibacterial and antiviral (i.e. cytotoxic) activity between aspirates of formula-fed infants and breast milk-fed infants. The disparity from the current results may be because food was sampled before it could be exposed to pancreatic enzymes, which as shown here can have a differential effect on breast milk versus formula.

We expect that, like formula and unlike breast milk, most food containing fat releases high concentrations of FFAs upon lipase digestion. Since unbound FFAs may be cytotoxic at concentrations as low as 1 μM (6), typical digested food is likely to be cytotoxic. An intact intestinal mucosal barrier must therefore provide protection for older children and adults from high concentrations of FFAs in digested food, though the exact mechanism of protection remains to be determined.

There are conditions, however, in which the mucosal barrier fails or is not yet fully present, such as during the intestinal ischemia prior to shock mentioned above. Likewise, the intestine is in an immature, permeable state at birth (20) that is even more permeable in pre-term infants (11). Both the neonatal intestine and breast milk appear to be optimized to reduce exposure of a permeable intestine to cytotoxic molecules. As we saw here, pancreatic lipase-digested breast milk has fewer FFAs and is less cytotoxic than lipase-digested formula. Digestion with pancreatic proteases reduces breast milk cytotoxicity even further, possibly by exposing new FFA binding sites within milk proteins. Breast milk also contains the neuropeptide somatostatin (21), which reduces the secretion of digestive enzymes into the lumen of the intestine (22). Prior to weaning, infants produce little to no pancreatic lipase, instead relying on pancreatic lipase-related protein 2 (PLRP2) and bile-salt sensitive lipase from the pancreas and milk (23), which, while having a broader specificity (able to cleave all three fatty acid positions in triglycerides and phospholipids as well), are actually less efficient at lipid digestion in milk than pancreatic lipase (18). In animal models, early weaning triggers full maturation of the intestine into an impermeable, adult state (24, 25). One reason for maturation as a response to diet transition may be to prevent influx of higher concentrations of unbound FFAs and pancreatic digestive enzymes like pancreatic lipase, necessary for digestion of nutrients other than milk, into the intestinal wall.

Given that digested full term formula is as cytotoxic as the preterm formula, it is also possible that full-term infants with a genetic predisposition to a permeable gut could be affected by this mechanism. For example, though their intestinal permeability as infants has not yet been studied, children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) have been reported to be more likely to have leaky guts (26, 27) and gastrointestinal problems (28). One study reported that infants fed exclusively on breast milk for longer periods are less likely to develop ASD compared to those weaned to formula earlier (29). Given that survivors of NEC have documented neurodevelopmental problems later in life (30), it is conceivable that the mechanism presented here may also play a role in ASD.

While we employed a broad range of enzyme concentrations, one limitation of the current study is that we used either isolated pancreatic lipase or the lipases from an adult rat for both the milk and formula digestions. We did not include pre-digestion by gastric and lingual lipases, which cleave only a small fraction of available ester bonds but may prime milk fats for further digestion in the intestine (31), nor did we include PLRP2 or exogenous bile-salt sensitive lipase. However, as mentioned above, PLRP2 may be even less efficient at lipid digestion in milk than pancreatic lipase (18), so neonates receiving fresh breast milk may be exposed to even lower FFA levels and be more protected from cytotoxicity than revealed by the current studies.

Our findings suggest a number of possible strategies to decrease the rate of FFA generation and limit cytotoxicity from formula for infants at risk for NEC or inherited conditions associated with permeable intestines. Formula may be further optimized by examining the risks versus benefits of decreasing the fat content or reducing the rate of lipolysis with pancreatic lipase through choice of fats, fat globule diameters, or by covering fat globules with a membrane similar to that around breast milk fat globules. Other possible methods to reduce cytotoxicity include the addition of fatty acid binding proteins and/or lipase inhibitors.

Overall, our results reveal a major ability of breast milk to reduce cytotoxicity that is not matched by formula, which may guide feeding practices of premature infants and infants with abnormal or increased intestinal permeability. It remains to be investigated via intestinal aspirates whether the actual intestinal luminal content of formula or breast milk fed infants is cytotoxic, whether there are significant differences in their free fatty acid profiles in vivo, and whether intervention to reduce unbound FFAs in the intestinal lumen can prevent intestinal damage and/or death in NEC in animal models.

Acknowledgments

Funding Disclosure: Supported by NIH grants NS071580 and GM85072.

We are grateful to the mothers who graciously donated their milk for use in this study and to Dr. Emily Blumenthal for her statistical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors have no financial interests or conflicts of interest to declare related to the contents of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Anand RJ, Leaphart CL, Mollen KP, Hackam DJ. The role of the intestinal barrier in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Shock. 2007;27:124–33. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239774.02904.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin PW, Stoll BJ. Necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:1271–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lucas A, Cole TJ. Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet. 1990;336:1519–23. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinzen-Derr J, Poindexter B, Wrage L, Morrow AL, Stoll B, Donovan EF. Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants’ risk of necrotizing enterocolitis or death. J Perinatol. 2009;29:57–62. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penn AH, Hugli TE, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Pancreatic enzymes generate cytotoxic mediators in the intestine. Shock. 2007;27:296–304. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235139.20775.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penn AH, Schmid-Schonbein GW. The intestine as source of cytotoxic mediators in shock: free fatty acids and degradation of lipid-binding proteins. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1779–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00902.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacs CE, Kashyap S, Heird WC, Thormar H. Antiviral and antibacterial lipids in human milk and infant formula feeds. Arch Dis Child. 1990;65:861–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.8.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Z, Wang X, Deng X, et al. The influence of intestinal ischemia and reperfusion on bidirectional intestinal barrier permeability, cellular membrane integrity, proteinase inhibitors, and cell death in rats. Shock. 1998;10:203–12. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang B, Huang Q, Zhang W, Li N, Li J. Lactobacillus plantarum prevents bacterial translocation in rats following ischemia and reperfusion injury. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3187–94. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1747-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosario HS, Waldo SW, Becker SA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Pancreatic trypsin increases matrix metalloproteinase-9 accumulation and activation during acute intestinal ischemia-reperfusion in the rat. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1707–16. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63729-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver LT, Laker MF, Nelson R. Intestinal permeability in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:236–41. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor SN, Basile LA, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Intestinal permeability in preterm infants by feeding type: mother’s milk versus formula. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4:11–5. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2008.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakaguchi M, Tomomasa T, Kuroume T. Cytolytic action of stored human milk on blood cells in vitro. J Perinat Med. 1995;23:293–300. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1995.23.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman A, Strandvik B, Ojamae O. Bile acids and pancreatic enzymes during absorption in the newborn. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1972;61:571–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1972.tb15947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng L, He Z, Chen W, Holzman IR, Lin J. Effects of butyrate on intestinal barrier function in a Caco-2 cell monolayer model of intestinal barrier. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:37–41. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250014.92242.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waligora-Dupriet AJ, Dugay A, Auzeil N, et al. Short-chain fatty acids and polyamines in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis: Kinetics aspects in gnotobiotic quails. Anaerobe. 2009;15:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalski MC, Briard V, Michel F, Tasson F, Poulain P. Size distribution of fat globules in human colostrum, breast milk, and infant formula. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88:1927–40. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72868-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berton A, Sebban-Kreuzer C, Rouvellac S, Lopez C, Crenon I. Individual and combined action of pancreatic lipase and pancreatic lipase-related proteins 1 and 2 on native versus homogenized milk fat globules. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53:1592–602. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lien EL, Boyle FG, Yuhas R, Tomarelli RM, Quinlan P. The effect of triglyceride positional distribution on fatty acid absorption in rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:167–74. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catassi C, Bonucci A, Coppa GV, Carlucci A, Giorgi PL. Intestinal permeability changes during the first month: effect of natural versus artificial feeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:383–6. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner H, Amarant T, Millar RP, Fridkin M, Koch Y. Immunoreactive and biologically active somatostatin in human and sheep milk. Eur J Biochem. 1985;148:353–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyr K, Beglinger C, Kohler E, Trautzl U, Keller U, Bloom SR. Circulating somatostatin. Physiological regulator of pancreatic function? J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1595–600. doi: 10.1172/JCI112994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Sanchez D, Figarella C, Lowe ME. Discoordinate expression of pancreatic lipase and two related proteins in the human fetal pancreas. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:184–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boudry G, Peron V, Le Huerou-Luron I, Lalles JP, Seve B. Weaning induces both transient and long-lasting modifications of absorptive, secretory, and barrier properties of piglet intestine. J Nutr. 2004;134:2256–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dvorak B, McWilliam DL, Williams CS, et al. Artificial formula induces precocious maturation of the small intestine of artificially reared suckling rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:162–9. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200008000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Eufemia P, Celli M, Finocchiaro R, et al. Abnormal intestinal permeability in children with autism. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1076–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Magistris L, Familiari V, Pascotto A, et al. Alterations of the intestinal barrier in patients with autism spectrum disorders and in their first-degree relatives. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:418–24. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181dcc4a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith RA, Farnworth H, Wright B, Allgar V. Are there more bowel symptoms in children with autism compared to normal children and children with other developmental and neurological disorders? A case control study Autism. 2009;13:343–55. doi: 10.1177/1362361309106418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schultz ST, Klonoff-Cohen HS, Wingard DL, et al. Breastfeeding, infant formula supplementation, and Autistic Disorder: the results of a parent survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2006;1:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neubauer AP, Voss W, Kattner E. Outcome of extremely low birth weight survivors at school age: the influence of perinatal parameters on neurodevelopment. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman C, Carriere F, Villeneuve P, et al. Quantitative and qualitative study of gastric lipolysis in premature infants: do MCT-enriched infant formulas improve fat digestion? Pediatr Res. 2007;61:83–8. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000250199.24107.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]