Abstract

Insects such as flies or bees, with their miniature brains, are able to control highly aerobatic flight maneuvres and to solve spatial vision tasks, such as avoiding collisions with obstacles, landing on objects, or even localizing a previously learnt inconspicuous goal on the basis of environmental cues. With regard to solving such spatial tasks, these insects still outperform man-made autonomous flying systems. To accomplish their extraordinary performance, flies and bees have been shown by their characteristic behavioral actions to actively shape the dynamics of the image flow on their eyes (“optic flow”). The neural processing of information about the spatial layout of the environment is greatly facilitated by segregating the rotational from the translational optic flow component through a saccadic flight and gaze strategy. This active vision strategy thus enables the nervous system to solve apparently complex spatial vision tasks in a particularly efficient and parsimonious way. The key idea of this review is that biological agents, such as flies or bees, acquire at least part of their strength as autonomous systems through active interactions with their environment and not by simply processing passively gained information about the world. These agent-environment interactions lead to adaptive behavior in surroundings of a wide range of complexity. Animals with even tiny brains, such as insects, are capable of performing extraordinarily well in their behavioral contexts by making optimal use of the closed action–perception loop. Model simulations and robotic implementations show that the smart biological mechanisms of motion computation and visually-guided flight control might be helpful to find technical solutions, for example, when designing micro air vehicles carrying a miniaturized, low-weight on-board processor.

Keywords: spatial behavior, optic flow, saccades, flying insects, obstacle avoidance, navigation behavior

Optic flow as an important spatial cue for fast moving animals

Behavior is a phenomenon that takes place in space and is intricately entangled with it. The organism is required to interact with its surroundings in a way appropriate to the respective situational context. It should be able to respond appropriately to objects, for instance, by avoiding collisions with obstacles or by detecting and fixating inanimate objects of interest or other organisms, such as a predator, prey, or mate. On a larger spatial scale, organisms should be able to navigate from one place to another and to localize a goal on the basis of environmental spatial cues.

Insects are obviously well able to cope with these behavioral challenges in a highly virtuosic and efficient way. Think of a blowfly, for example, landing on the rim of a cup, or two flies chasing each other; without technical assistance, our visual system is incapable of resolving the complexity of such flight maneuvres, and the speed at which they are executed exceeds by far the capacities of our own motor system. During their virtuosic flight maneuvres, blowflies can make up to ten sudden (“saccadic”) turns per second, during which they may reach angular velocities of up to 4000°/s. The extraordinary navigational skills of bees are another awe inspiring example of insect spatial behavior: spatial cues enable bees to localize previously learnt, barely visible goals, such as a food source or the entrance to their nest, over large distances even in cluttered environments. All these feats are accomplished with visual systems of comparatively poor spatial resolution and extremely small brains that consist of no more than a million neurons, underlining the resource efficiency of the underlying mechanisms.

We will argue in this review that biological agents, such as flying insects, are such efficient and adaptive autonomous systems because they rely, to a large extent, on strategies by which they shape their sensory input through the specific way they move and change their gaze direction. In this way, they actively reduce the complexity of their sensory input and, thus, the computational load for the underlying brain mechanisms. Therefore, by exploiting the consequences of the action–perception cycle, animals with even tiny brains, such as insects, are enabled to perform extraordinarily well in solving spatial vision tasks in a wide range of behavioral contexts. This view somehow contrasts with common conceptions of how spatial vision is accomplished.

If laypeople are asked for the requirements of spatial vision, they are likely to reply that most animals, including humans, are equipped with two eyes which allow them to view the world from slightly different vantage points, and that the nervous system makes use of the resulting disparity information for depth vision. However, the spatial range that can be resolved in this way is critically restricted by the distance between the eyes, the overlap of their visual fields and their spatial resolution (Collett and Harkness, 1982). Hence, stereoscopic vision—if it is available at all to a particular animal species—is functional only in the near range. This poses a problem, especially for fast moving animals, such as many flying insects (as well as for human car drivers), because, in order to control appropriate reactions, such as avoiding collisions with obstacles, spatial information is required at much greater distances than may be available through stereoscopic mechanisms. Amongst the depth cues that are available in addition to binocular information, for example, contrast differences between near and distant objects (Collett and Harkness, 1982), the retinal image motion induced by self-movements of the animal (“optic flow”) is particularly relevant (Koenderink, 1986; Rogers, 1993; Poteser and Kral, 1995; Lappe, 2000; Redlick et al., 2001; Vaina et al., 2004).

Whenever an animal moves in its environment, the retinal images are continually displaced. During translatory movements, these displacements depend on the distance of environmental objects to the eyes, their angular location relative to the direction of motion and the velocity of locomotion. Only translational optic flow is distance dependent and, thus, contains spatial information, whereas rotational optic flow is useless for spatial vision, because all objects during rotations are displaced at the same angular velocity irrespective of their distance (Figure 1; Koenderink, 1986). Hence, the translatory optic flow component contains information about the relative distance of environmental objects from the animal: objects nearby pass quickly, while objects far-off appear virtually stationary. This motion-induced spatial information is based on behavioral action, because it is only available during self-motion, but not when the animal is stationary. Many animals, ranging from insects to humans, were concluded to exploit optic flow information for depth cueing.

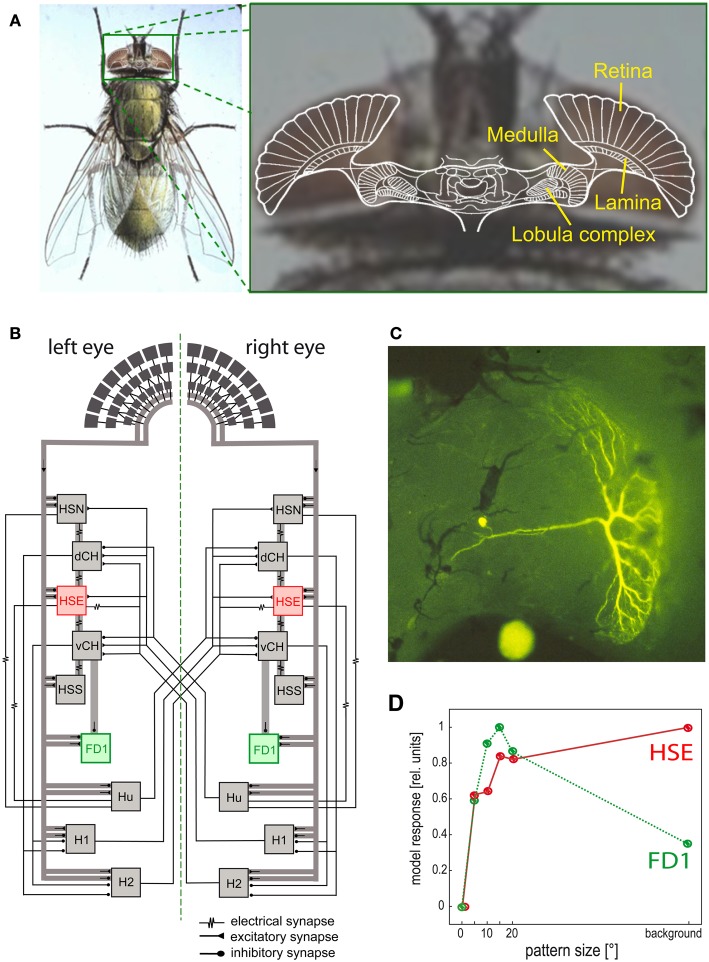

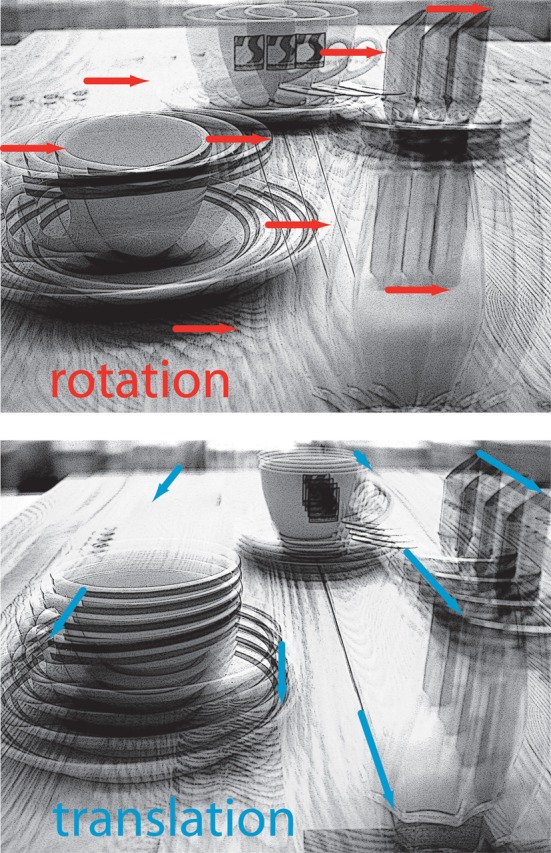

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the consequences of rotational (upper diagram) or translational self-motion (bottom diagram) for the resulting optic flow. Superimposed images were either generated by rotating a camera around its vertical axis or by translating it forward. Rotational self-motion leads to image movements (red arrows) of the same velocity (reflected in the arrow length) irrespective of the distance of environmental objects from the observer. In contrast, the optic flow elicited by translational self-motion (blue arrows) depends on the distance between objects from the observer. Hence, translational optic flow contains spatial information.

We will focus in this review on the spatial behavior of insects that is based on depth information derived from optic flow. Since optic flow is particularly relevant during fast locomotion in three dimensions, we will mainly cover spatial vision in flight and address four major issues: (1) Components of insect behavior that are thought to be involved in solving basic spatial tasks and how they may depend on motion-based information; (2) the processing of motion-dependent spatial information and how it is facilitated by active gaze movements; (3) the representation of behaviorally relevant spatial information in the visual system; and (4) the behavioral significance of neurons extracting information about self-motion of the animal, as well as the environment, from the image flow generated on the eyes as a consequence of the action–perception loop being closed. Obviously, solving any spatial vision task—especially by flying insects that lack passive stability—requires, as a precondition, the animal's flight attitude to be somehow stabilized by appropriate feedback control systems. This issue, though very important for spatial orientation behavior and widely analysed for decades, will be touched on only briefly, because it has already been thoroughly reviewed (Hengstenberg, 1993; Taylor and Krapp, 2008).

Behavior involved in spatial tasks and its control by visual motion cues

Many animals, including humans, use optic flow for the control of spatial behavior. Since spatial information can most easily be extracted from the retinal image flow during translatory self-motion, some animals execute translatory movements of their body and/or head that appear to be dedicated to generate optic flow suitable for depth cueing. Locusts, mantids, and dragonflies, for instance, sitting in ambush perform lateral body and head movements in preparation for a jump or for catching prey, respectively (Collett, 1978; Sobel, 1990; Collett and Paterson, 1991; Kral and Poteser, 1997; Olberg et al., 2005). Some bird species bob their heads back and forth, most likely to acquire depth information (Davies and Green, 1988; Necker, 2007). Moreover, flying insects, such as flies and bees (Schilstra and van Hateren, 1999; Boeddeker et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2010, 2012; Geurten et al., 2010), but also birds (Eckmeier et al., 2008), perform a saccadic flight and gaze strategy in which short and rapid head and body saccades are separated by largely translatory locomotion. This strategy facilitates access to spatial information from the resulting optic flow.

The use of optic flow to gain spatial information has been shown most convincingly in behavioral experiments in which animals responded to objects that were camouflaged by covering them with the same texture as their background. Thus, these objects could be discriminated only on the basis of optic flow cues elicited during self-motion. Drosophila, for instance, is well able to discriminate the distance of different objects on the basis of slight differences in their retinal velocities (Schuster et al., 2002). Bees (Srinivasan et al., 1987; Lehrer et al., 1988) and blowflies (Kimmerle et al., 1996) use relative motion cues mainly at the edges of objects to discriminate between their height and to land on them (Figure 2A; Srinivasan et al., 1990; Kimmerle et al., 1996; Kern et al., 1997). Bees also use motion contrast in discrimination tasks (Lehrer and Campan, 2005) and for navigating back to the previously learnt location of a barely visible goal (Figure 2C; see below; Dittmar et al., 2010). Moreover, hawk-moths hovering in front of a flower use motion cues to control their distance to the nectar donating blossom (Pfaff and Varjú, 1991; Farina et al., 1994; Kern and Varjú, 1998). However, motion information is also used for spatial tasks that are not related to objects. Bees, for instance, exploit optic flow information to estimate distances traveled during navigation flights. The dependence of optic flow information on the depth structure of the environment is also relevant in this context: experimental manipulation of the environment between flights can induce characteristic errors in distance estimation because estimates of distances traveled in a given environment cannot be generalized to environments with different depth structures (Srinivasan et al., 2000; Esch et al., 2001; review: Wolf, 2011).

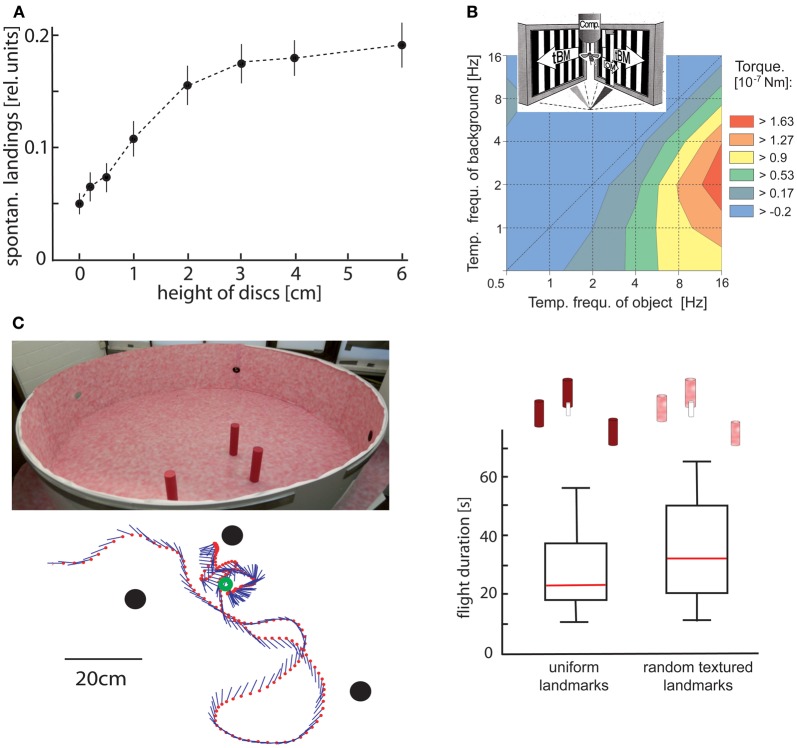

Figure 2.

Object detection by relative motion cues. (A) Relative number of spontaneous landings of free-flying flies on discs covered with a random texture of different heights. The floor and walls of the flight arena were covered with the same texture. Hence, the discs could only be discriminated by relative motion cues induced on the eyes by the self-motion of the animal. Flies landed on discs raised at least 1 cm above the floor significantly more often than on a reference disc on the floor (data from Kimmerle et al., 1996). (B) Contour plot of the turning responses of tethered flying flies measured with a yaw torque compensator (comp) for different combinations of temporal frequencies of object motion (OM) and translatory background motion (tBM). The motion stimuli were striped patterns (spatial period 6.3°) presented on two monitor screens placed at an angle of 90° symmetrically in front of the fly. OM was displayed within a vertical 6.3° wide window in front of the right eye. Object-induced responses are given in a color coded way with warmer colors indicating larger responses. Flies show strong turning responses when OM is faster than tBM. The strongest responses are induced when the background is not stationary, but moves slowly (data from Kimmerle et al., 1997). (C) Landmark navigation of honeybees in a cylindrical flight arena with three cylindrical landmarks (upper left diagram). The landmarks were either homogeneously red or were covered by the same random pattern as the background. Bees were trained to find a barely visible feeder placed between the homogeneous landmarks. The trajectory of one search flight maneuvre is shown in the top view (bottom left diagram). The feeder (green circle) and the landmarks (black dots) are indicated. The position of the bee is indicated by red dots at each 32 ms interval; straight lines represent the orientation of the long axis of the bee. The duration of search flights until landing on the feeder was not significantly increased when the pattern of the landmarks was changed from homogeneous red to the random dot texture that also covered the background (right diagram). Red lines indicate median values, the upper and lower margins of the boxes, the 75th and 25th percentiles; the whiskers indicate the data range (Data from Dittmar et al., 2010).

What are the mechanisms involved in solving spatial behavioral tasks? Insects play a pivotal role in systems analyses of these mechanisms, both at the behavioral and the neural level. Behavioral systems analyses have been mainly performed in flight simulators on tethered flying flies, because the visual input can be perfectly controlled by the experimenter while, in most experimental paradigms, turning responses are recorded. Here, the visual consequences of locomotion are emulated by motion stimuli to which the tethered animal is exposed. However, the degrees of freedom of movement that can be executed by the animal and monitored by the experimenter in these behavioral paradigms are constrained, thus providing only limited access to the rich behavioral repertoire of the animal. Apart from a few exceptions (e.g., Land and Collett, 1974; Collett and Land, 1975; Wagner, 1982; Zeil, 1986), it has only recently become possible to investigate spatial behavior systematically under free-flight conditions with high spatial and temporal resolution and to also reconstruct what an animal has seen during largely unconstrained behavior (Lindemann et al., 2003). In the following, we restrict the review to only a few components of spatial behavior that have been experimentally investigated in detail.

Object detection and object-directed responses

It has been known for a long time from experiments in tethered flight that flies can discriminate objects from their background on the basis of motion cues and attempt to fixate them in the frontal visual field (Virsik and Reichardt, 1976; Reichardt and Poggio, 1979; Reichardt et al., 1983; Egelhaaf, 1985a; Egelhaaf and Borst, 1993a; Kimmerle et al., 1997, 2000; Maimon et al., 2008; Aptekar et al., 2012). In these experiments, the tethered animal could not move, and only its yaw torque was measured. Relative motion was generated by specifically controlling object and background displacements. In real life, this situation usually occurs as a consequence of the action–perception cycle being closed while the animal moves in a three-dimensional environment and actively generates relative motion cues on its eyes through its behavior (see above).

Only three features of the control system mediating object detection in flies will be mentioned here. (1) The detectability of objects depends to a large extent on the dynamical properties of object and background motion. Object detection is facilitated if the background moves at a moderate velocity, such as during translation in an environment where the background is at a medium distance from the animal (Figure 2B) (Kimmerle et al., 1997). (2) The visual pathways extracting motion-dependent object information and those processing other types of motion information (e.g., those controlling compensatory optomotor responses or translation velocity) are commonly assumed to segregate at the level of the fly's third visual neuropile. The object system appears to be distinguished by its dynamical and other properties. In particular, the object system responds to high-frequency changes of the retinal position and velocity of the object, whereas strong compensatory optomotor responses are evoked by low-frequency velocity changes (Egelhaaf, 1987; Aptekar et al., 2012). The object pathway appears to be kept separate from the other pathways up to the level of the steering muscles that mediate object-induced turns (Egelhaaf, 1989). (3) Even when the object moves exactly in the same way in subsequent stimulus presentations, it may either be fixated by the fly or no fixation responses may be elicited at all. Such a bimodal distribution of responses in the behavioral context of object detection—a full response or no response—suggests a gating mechanism in the neural pathway mediating motion-induced object fixation (Kimmerle et al., 2000).

Currently we can only speculate about the functional significance under real-life conditions of a control system that induces turning responses in tethered flight toward an object moving in front of its background. Potentially, an object may initiate landing behavior under free-flight conditions. This is plausible in blowflies as well as in bees, because (1) an object is most effective in eliciting fixation responses when the ventral part of the visual field is stimulated (Virsik and Reichardt, 1976), and (2) when detecting and approaching a landing site in free-flight, relative motion cues are exploited mainly in the ventral visual field (Wagner, 1982; Lehrer et al., 1988; Kimmerle et al., 1996; Kern et al., 1997; van Breugel and Dickinson, 2012). Similar object-detection systems could play an important role in bees during local navigation when landmarks based on contrast, texture, and relative motion cues need to be detected to guide the animal to its goal (see below).

Collision avoidance

In many situations, objects or other structures in the environment (e.g., extended surfaces, such as walls) are not goals the animal may aim for, but may interfere with the animal's trajectory as obstacles that need to be avoided. Thus, collision avoidance represents a basic, but highly relevant spatial task. Again, optic flow has been shown in a variety of animals, including humans, to be one of the most relevant cues that may signal an impending collision (e.g., Lappe, 2000; Vaina et al., 2004).

Optic flow has been shown to be relevant in collision avoidance behavior for both tethered and free-flying flies. There is consensus amongst studies that asymmetries in the optic flow across the two eyes, for instance, when approaching environmental structures on one side, are decisive for eliciting collision avoidance responses: (1) Flies tend to turn away from the eye experiencing image expansion (Tammero and Dickinson, 2002a,b; Tammero et al., 2004; Bender and Dickinson, 2006b; Budick et al., 2007; Reiser and Dickinson, 2010). (2) The probability of eliciting an evasive turn has been concluded to be highest if the focus of image expansion is located in the lateral rather than in the frontal part of the visual field (Tammero and Dickinson, 2002a; Tammero et al., 2004; Bender and Dickinson, 2006b). Such optic flow might occur during flights with a strong sideways component. These results do not imply that the focus of expansion in the retinal motion pattern during object approach is explicitly extracted by the neuronal circuits that mediate collision avoidance. Based on experiments done in free-flight in different types of flight arenas that allow for more complex behavior than in tethered flight, mechanisms that rely on asymmetries in the optic flow field across the two eyes other than explicitly extracting the focus of expansion are well able to account for relevant aspects of collision avoidance (see below; Lindemann et al., 2008; Mronz and Lehmann, 2008; Kern et al., 2012).

Interaction between object fixation and collision avoidance

Expanding visual flow fields are encountered by flying insects not only when they encounter an obstacle, but also when flying straight toward an object that may serve as a landing site or as a landmark in the context of navigation behavior. As sketched above, tethered flying Drosophilae turn away from an expanding retinal image. Given the strength of this evasive response, it is difficult to explain how flies can fly straight in natural surroundings with ample objects surrounding them. This apparent paradox is partially resolved by the finding that Drosophila, when flying toward a conspicuous object, tolerates a level of expansion that would otherwise induce avoidance (Reiser and Dickinson, 2010). This suggests that the gain of the control system mediating evasive turns is reduced if prominent visual features are attractive and represent a behavioral goal. Therefore, flies appear to require a goal to keep an overall flight direction, either toward a salient object (Heisenberg and Wolf, 1979; Götz, 1987; Maimon et al., 2008; Reiser and Dickinson, 2010), toward an attractive odorant (Budick and Dickinson, 2006), when flying upwind (Budick et al., 2007), or while pursuing a moving target such as a potential mate (Trischler et al., 2010).

Spatial information relevant for local navigation

Whereas collision avoidance and landing are spatial tasks that must be solved by any flying insect, local navigation is relevant especially for particular insects, such as bees, some wasps and ants, which care for their brood and, thus, have to return to their nest after foraging. Consequently, the full complexity of spatial navigation has been analysed mainly in bees, wasps, and ants both in artificial and natural environments. Nonetheless, basic elements of local navigation could be found also in Drosophila (Foucaud et al., 2010; Ofstad et al., 2011). Since various aspects of insect navigation and the underlying mechanisms have been reviewed recently (Collett and Collett, 2002; Collett et al., 2006; Zeil et al., 2009; Zeil, 2012), only selected issues will be addressed here, and spatial information processing during flight will be the major focus.

Visual landmarks represent crucial spatial cues and are employed to localize a goal, especially if it is barely visible itself. Information about the landmark constellation around the goal is memorized during elaborate learning flights: the animal flies characteristic sequences of ever increasing arcs while facing the area around the goal. During these learning flights, the animal somehow gathers relevant information that is subsequently used to relocate the goal when returning to it after an excursion. A variety of visual cues, such as contrast, texture and color, are suitable to define landmarks and are employed to find the goal (reviews: Collett and Collett, 2002; Collett et al., 2006; Zeil et al., 2009; Zeil, 2012). Recently, landmarks that are defined by motion cues alone were shown to be sufficient for bees to locate the goal (Dittmar et al., 2010). In this study, several landmarks that were camouflaged by their texture and, thus, could not be discriminated from the background by stationary cues were placed in particular locations surrounding the goal (Figure 2C). The mechanisms by which the landmark constellation is learnt and how the memorized information is eventually used to locate the goal are not yet fully understood. However, it is clear that optic flow information generated actively during the bees' typical learning and searching flights is essential for the acquisition of a spatial memory of the goal environment. Moreover, in the vicinity of the landmarks, the animals were found to adjust their flight movements according to specific textural properties of the landmarks (Dittmar et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2012).

Landmarks close to the goal are, for geometrical reasons, most suitable to define the goal location, because the retinal locations of close landmarks are displaced more than distant ones during the translational movements of the animal (Stürzl and Zeil, 2007). Emerging as a direct consequence of the closed action–perception cycle, this property “weighs” the relevance of environmental objects to serve as landmarks for local navigation in the vicinity of the goal.

Spatial information based on saccadic gaze and flight strategy

Saccadic gaze changes have a rather uniform time course and are shorter than 100 ms. Angular velocities of up to several thousand °/s can occur during saccades (Figure 3). Since roll movements of the body that are performed for steering purposes during saccades, and also during sideways translations, are compensated by counter-directed head movements, the animals' gaze direction is kept virtually constant during intersaccades (Schilstra and van Hateren, 1999; Boeddeker and Hemmi, 2010; Boeddeker et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2010, 2012; Geurten et al., 2010, 2012). Saccade dynamics in flies have been shown to be fine-tuned by mechanosensory feedback from the halteres, the gyroscopic sense organs of dipteran flies, evolutionarily developed from the hind wings. Haltere feedback may thus contribute to increasing the duration of intersaccadic intervals (Sherman, 2003; Bender and Dickinson, 2006a). Nevertheless, halteres are no prerequisite for a saccadic gaze strategy, given that bees and wasps show similar flight dynamics as flies without halteres (Figure 3) (Boeddeker et al., 2010). By squeezing body and head rotations into the brief saccades, translational gaze displacements last for more than 80% of the entire flight time (van Hateren and Schilstra, 1999; Boeddeker and Hemmi, 2010; Boeddeker et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2010, 2012; van Breugel and Dickinson, 2012).

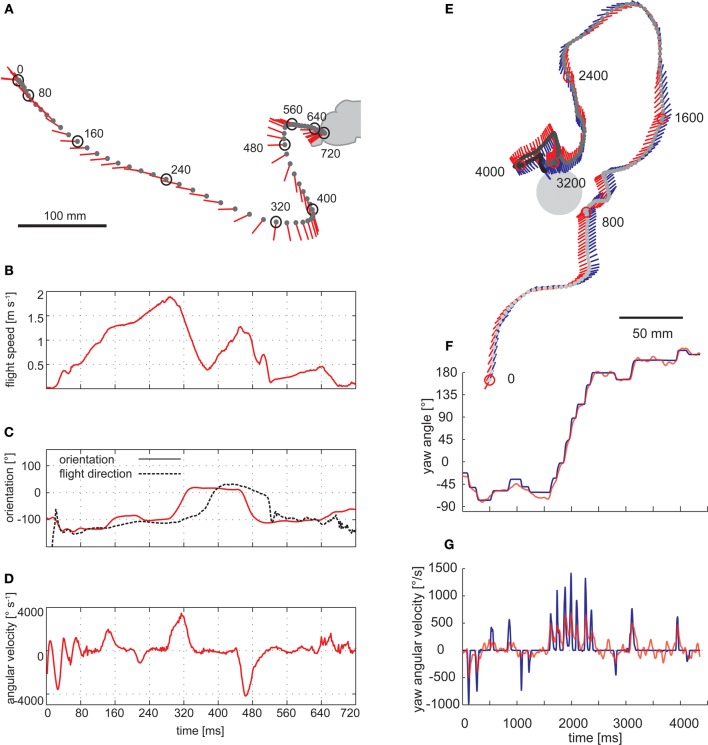

Figure 3.

Saccadic flight and gaze strategy of free-flying blowflies and honeybees. (A) Sample flight trajectory of a blowfly as seen from above. The position of the fly (black dot) and the orientation of the longitudinal body axis (red line) are shown every 10 ms. The trajectory was filmed outdoors: the fly took off from a perch and landed on a leaf of a shrub. (B) Translational flight speed. (C) Orientation of the fly's longitudinal body axis (solid red line) and flight direction (broken black line) in the external coordinate system. (D) Angular velocity of the fly. The fly changed its gaze and heading direction through a series of short and fast body turns. Flight direction and body axis orientation frequently deviate: the body axis already points in the new flight direction while the fly is continuing to move on its previous course. (A–D) Data from Boeddeker et al. (2005). (E) Top view of a flight of a honeybee eventually landing on a feeder. The position of the bee's head (gray dot) is shown every 16 ms. The orientation of the head (blue line) and body (red line) can deviate considerably. (F) Head (blue) and body orientation (red). The head usually turns with the thorax but at a higher angular speed, starting, and finishing slightly earlier. (G) Head (blue) and body (red) angular velocity. (E–G) Data from Boeddeker et al. (2010).

It should be noted that flying insects may appear to meander smoothly when their overall flight trajectory is inspected (Boeddeker et al., 2005; Kern et al., 2012). Having frequently been an issue of misunderstandings, this smoothness does not contradict a saccadic flight style. As a consequence of inertial forces, flying insects, in particular large ones, may move for some time after a saccadic change in body orientation in their previous direction. Thus, the saccadic gaze strategy is reflected only to some extent in the overall flight trajectories. (Figure 3). This may be different in the much smaller Drosophila where at least some rapid large-amplitude turns can be seen in the overall flight trajectories (Tammero and Dickinson, 2002b).

Blowflies do not fly exactly straight even in straight flight tunnels without any obstacles. Rather they perform sequences of saccades, alternating their direction and the saccade amplitude depending on the clearance of the animal with respect to the walls of the flight tunnel (Kern et al., 2012). A saccadic flight style may be functionally relevant, even if the overall flight course pursued by the animal is straight. This is because the animal normally has no prior knowledge about the spatial structure of the environment. Thus, the uncertainty about whether it can fly on a straight course or not needs to be resolved on the basis of optic flow information. Regular changes of flight and gaze direction might, therefore, be a useful flight strategy, because it would allow the animal to check (during intersaccadic intervals) the translational optic flow for environmental information (Kern et al., 2012).

Since the saccadic flight and gaze strategy leads to either primarily rotational or primarily translational optic flow on the eyes, it can be interpreted as a behavioral adaptation to facilitate spatial vision. This is because only translational optic flow depends on the distance of the animal to environmental objects and, thus, contains spatial information (see above). A segregation of optic flow fields into their rotational and translational components can, at least in principle, be accomplished computationally for most realistic situations (Longuet-Higgins and Prazdny, 1980; Prazdny, 1980; Dahmen et al., 2000). However, such a computational strategy for the nervous system appears to be a lot more demanding than preventing the formation of composite rotational and translational optic flow by behavioral means. Thus, a saccadic gaze and flight strategy can be regarded as an efficient way to provide the nervous system with input from which spatial information can be extracted with relatively little computational effort.

Control of saccades as the main rotational components of flight behavior

The saccadic gaze strategy of insects has been characterized in various functional contexts: flies exhibit a saccadic flight pattern during spontaneous behavior, for instance, when cruising around without any obvious goal. This was shown in a wide range of environments including outdoors conditions (Figure 3A). Saccade frequencies of up to 10 per second were observed (Schilstra and van Hateren, 1999; van Hateren and Schilstra, 1999; Tammero and Dickinson, 2002b; Boeddeker et al., 2005, 2010; Braun et al., 2010, 2012; Dittmar et al., 2010; Geurten et al., 2010). The direction, amplitude and frequency of saccades depend not only on the spatial outline, but also on the texture of the environment. Thus, saccades are, at least to some extent, under visual control and serve purposes in spatial behavior, such as in collision avoidance behavior (Frye and Dickinson, 2007; Geurten et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2012; Kern et al., 2012).

There is consensus that intersaccadic optic flow during collision avoidance behavior plays a decisive role in controlling the direction and amplitude of saccades. However, which optic flow parameters may be most relevant is still inconclusive. Notwithstanding, all proposed mechanisms of evoking saccades rely on some sort of asymmetry in the optic flow pattern in front of the two eyes. The asymmetry may be due to the location of the expansion focus in front of one eye or to a difference between the overall optic flow in the visual fields of the two eyes (Tammero and Dickinson, 2002b; Lindemann et al., 2008; Mronz and Lehmann, 2008; Kern et al., 2012).

Not all of the visual field has been concluded to be involved in saccade control, at least for blowflies. The optic flow in the lateral parts of the visual field does not play a role in determining saccade direction (Kern et al., 2012). This feature might be related to the way in which blowflies fly: during intersaccades, they predominantly fly forwards with some sideways component after saccades that shifts the pole of expansion of the flow field slightly toward frontolateral locations (Kern et al., 2012). In contrast, in Drosophila—which are able to hover and fly sideways (Ristroph et al., 2009)—lateral and even rear parts of the visual field have also been shown to be involved in saccade control. Therefore, in Drosophila, a mechanism that also takes lateral retinal areas into account for saccade control is plausible from a functional point of view (Tammero and Dickinson, 2002b).

Control of intersaccadic translational motion

Whereas saccades are fairly stereotyped across different behavioral contexts, the intersaccadic translational movements may vary to a much larger extent, depending on the behavioral context as well as the spatial layout of the environment (Braun et al., 2010, 2012). This aspect has been addressed systematically in two different behavioral contexts: (1) The dependence of translation velocity on the spatial layout of the environment, and (2) the control of translational movements during visual landmark navigation in the vicinity of an invisible goal.

Insects tend to decelerate when their flight path is obstructed. Flight speed is thought to be controlled by optic flow generated during translational flight (David, 1979, 1982; Farina et al., 1995; Kern and Varjú, 1998; Baird et al., 2005, 2006, 2010; Frye and Dickinson, 2007; Fry et al., 2009; Dyhr and Higgins, 2010; Straw et al., 2010; Kern et al., 2012). Flies, bees, and moths were concluded to keep the optic flow on their eyes at a “preset” total strength by adjusting their flight speed. Accordingly, they decelerate when the translational optic flow increases, for instance, while passing a narrow gap or flying in a narrow tunnel (Figures 4A,B) (Srinivasan et al., 1991, 1996; Verspui and Gray, 2009; Baird et al., 2010; Portelli et al., 2011; Kern et al., 2012). However, not all parts of the visual field contribute equally to the input of the velocity controller. Whereas the intersaccadic optic flow generated in eye regions looking well in front of the insect has a strong impact on flight speed, the lateral visual field plays only a minor role (Baird et al., 2010; Portelli et al., 2011; Kern et al., 2012).

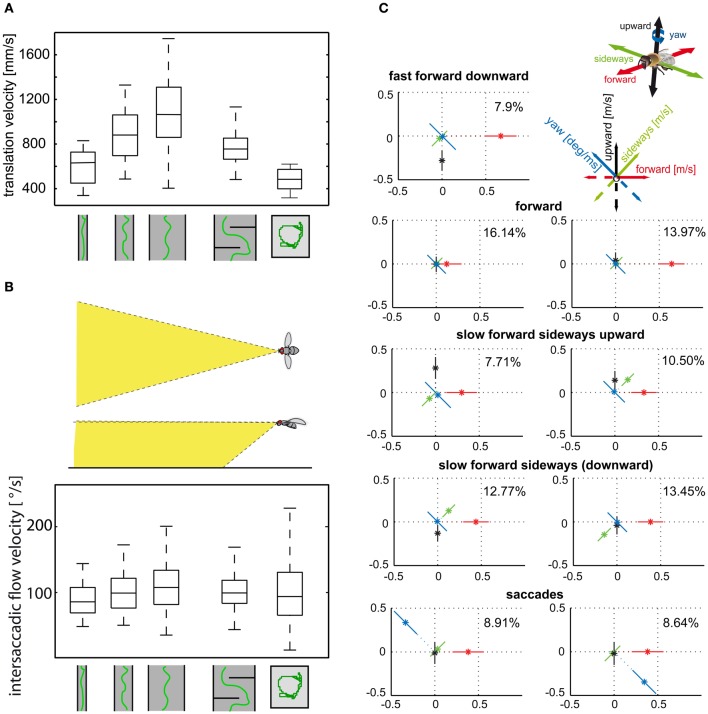

Figure 4.

(A) Control of translational velocity in blowflies. Boxplot of the translational velocity in flight tunnels of different widths, in a flight arena with two obstacles and in a cubic flight arena (sketched below data). Translation velocity strongly depends on the geometry of the flight arena. (B) Boxplot of the retinal image velocities within intersaccadic intervals experienced in the fronto-ventral visual field (see inset) in the different flight arenas. In this area of the visual field, the intersaccadic retinal velocities are kept roughly constant by regulating the translation velocity according to clearance with respect to environmental structures. The upper and lower margins of the boxes in (A) and (B) indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles, and the whiskers the data range (Data from Kern et al., 2012). (C) Translational and rotational prototypical movements of honeybees during local landmark navigation (see example in Figure 2C). Homing flight sequences can be decomposed into nine prototypical movements using clustering algorithms in order to reduce the behavioral complexity. Each prototype is depicted as a star plot containing the four velocity components drawn onto color-coded lines equally dividing the drawing plane (see inset). For each line, the distance of the dot from the center determines the value of the corresponding velocity component, and the error bars give the standard deviation of this value. Percentage values provide the relative occurrence of each prototype. More than 80% of flight-time corresponds to a varied set of translational prototypical movements and less than 20% has significantly non-zero rotational velocity corresponding to the saccades (Data from Braun et al., 2012).

Translational flight maneuvres during the spatial navigation of bees have a particularly elaborate fine structure and can be described by a distinct set of prototypical movements (Figure 4C). The optic flow generated during flight sequences close to visual landmarks appears to be systematically employed to localize a virtually invisible goal. Not only the overall velocity, but also the relative distribution of sideways and forward translational movements depend on the insect's distance and orientation relative to the landmarks and the goal (Zeil et al., 2009; Dittmar et al., 2010, 2011; Braun et al., 2012; Zeil, 2012). Bees, for example, frequently tend to perform translational movements with a strong sideways component close to landmarks, as if they wanted to scrutinize them in detail. These sideways movements are more pronounced if the landmarks are camouflaged by the same texture as their background and, thus, can be detected only by relative motion cues in the optic flow fields (Dittmar et al., 2010; Braun et al., 2012).

Processing of optic flow in the insect nervous system

Separating the rotational and translational optic flow components behaviorally can be viewed as an efficient strategy to reduce the computational load for the nervous system when extracting information about the environment and, especially, about its spatial layout. Nonetheless, the retinal image flow resulting from the closed action–perception cycle still has complex spatiotemporal properties, and its processing represents a demanding challenge for the nervous system. In particular, there is not much time for gathering environmental information between saccades. With up to 10 saccades per second being generated, intersaccadic intervals may be as short as only a few ms and rarely longer than 100–200 ms. Time is a critical issue for at least three reasons: (1) All neural processing is time-consuming, beginning with the biophysical mechanisms of signal transduction in the photoreceptors, and ending with transmitter signaling at neuromuscular junctions. (2) Sensory input is encoded by nerve cells with only limited reliability. Repeated presentation of the same input may lead to variable neural responses, which constrain the information which can be transmitted within a given time interval. (3) Neural computations are not necessarily rigid, but may flexibly adjust to the prevailing stimulus conditions. To be functionally beneficial, the time constants of such adaptive processes need to match the behaviorally relevant timescale of changes of the various visual stimulus parameters.

These three issues become particularly challenging if information is to be processed and represented with sufficient reliability on the very short timescales that are behaviorally relevant for fast flying insects. The virtuosity of the spatial behavior of many insects is proof that their sensory and nervous systems somehow cope successfully with this challenge. Since insects accomplish all this with very small brains comprising only a million or less neurons, they seem to be champions of resource efficient information processing and behavioral control.

So far, we only have vague conceptions of how all this is accomplished. In the following, we briefly sketch the available knowledge about the processing of retinal image flow. Particular focus is placed on how the spatiotemporal properties of image flow are shaped by the closed action–perception cycle.

Spatiotemporal visual input of insects is shaped by active gaze strategies

From what has been sketched above, it may be obvious that the spatiotemporal characteristics of the input to the visual system will depend strongly not only on the features of the behavioral surroundings, but also on the specific dynamical characteristics of locomotion. These movements, resulting from the closed-loop nature of the behavior, may, in turn, depend on the environmental properties. The statistical properties of a wide variety of natural scenes have been characterized in many studies. The scenes analysed were usually stationary, or they resulted from movements either at constant velocities or with dynamics that differ a lot from that of unrestrained gaze changes during natural locomotion (e.g., Eckert and Buchsbaum, 1993; Dong and Attick, 1995; van Hateren, 1997; Simoncelli and Olshausen, 2001; Betsch et al., 2004; Geisler, 2008). In a recent study, we simulated the natural dynamics of the saccadic gaze strategy of insects and registered the resulting image sequences in a large variety of natural environments (Schwegmann et al., in preparation).

Given the characteristic temporal structure of behavioral dynamics, the parameters within these image sequences also change in a temporally structured way. Two aspects of such changes may be particularly relevant for extracting behaviorally relevant environmental information from the retinal image flow: (1) Relevant image parameters, such as brightness, contrast, and spatial frequency composition, vary according to image region and viewing direction, and fluctuate more rapidly during saccadic turns than during intersaccades. (2) During translatory intersaccadic movements, image parameters resulting from close structures fluctuate in general much more than those resulting from distant structures (Figure 5).

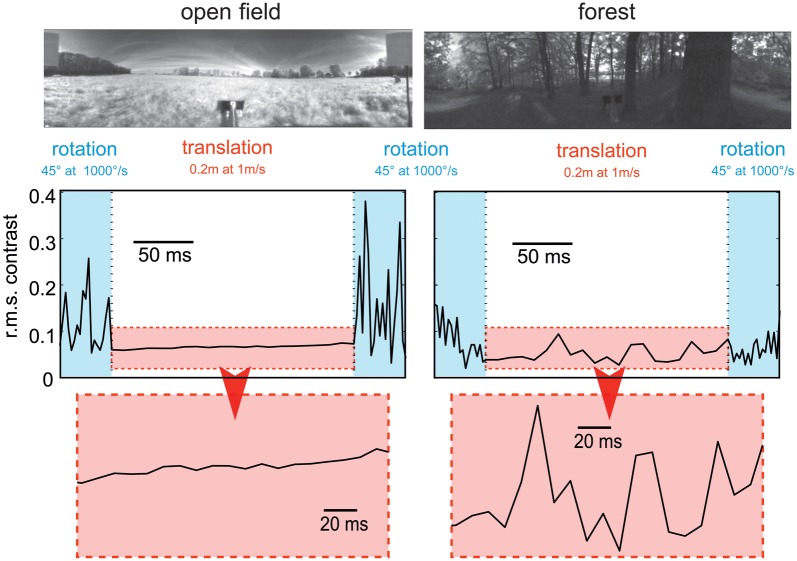

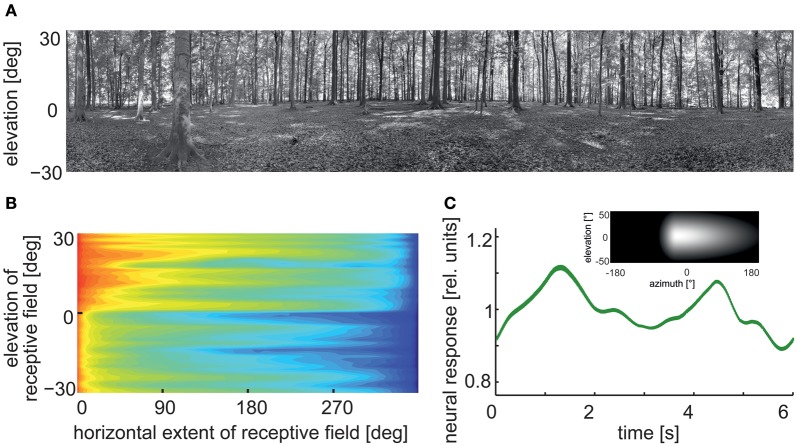

Figure 5.

Consequences of flight dynamics for contrast fluctuations in a small patch (2 × 2°, corresponding to approximately the aperture of a local movement detector) of the visual field at the equator and 90° relative to the direction of motion in two typical environments: an open field (left column) and a forest (right column). The movement sequence of the panoramic camera system corresponds to an initial 45° rightward rotation at a saccade-like angular velocity (1000°/s), followed by a translation for 20 cm at a velocity of 1 ms and then another 45° rightward turn. In general, contrast fluctuations are much larger during saccade-like turns than during translational phases. If environmental objects are relatively close (as in the forest environment), translations may also lead to considerable contrast fluctuations, though on a slower timescale. The data are based on high dynamic range image sequences, which are rescaled to the printable contrast range. (Data from Schwegmann et al., in preparation).

The dynamical properties imposed by the saccadic gaze change and the image statistics of natural environments constrain the time constants of information processing. Furthermore, the adaptive mechanisms that are thought to adjust the sensitivity of the visual system to the prevailing stimulus conditions have to operate on a suitable timescale. In particular, to optimize the encoding of the fluctuations of environmental image features during the intersaccadic intervals, adaptation in the visual system should essentially take place on a timescale shorter than the duration of these intervals (i.e., within some tens of milliseconds) and may be driven by the high-frequency changes of the respective image parameters. Several physiological components of motion adaptation have been described at the different levels of the fly visual system (e.g., Maddess and Laughlin, 1985; Brenner et al., 2000a; Harris et al., 2000; Fairhall et al., 2001; Kurtz, 2007; Kalb et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008). To what extent the time constants of these processes, which have been identified with experimenter designed motion stimuli, match the dynamics of parameter changes in the natural visual input, and how these adaptive processes are controlled, is still not clear.

Peripheral processing of motion information

How is the environmental and, in particular, the spatial information extracted from the retinal image flow and represented in the visual motion pathway? The retinal input is transformed at the level of photoreceptors in basically two ways: (1) The retinal input is sampled by the array of photoreceptors. Compared with technical imaging systems, the number of image points and, thus, the spatial resolution is very low, with only approximately 750 image points per eye in Drosophila (Hardie, 1985), 5000 in the blowfly Calliphora (Beersma et al., 1977) and 5400 in honeybees (Seidl and Kaiser, 1981). The visual angle between photoreceptors is matched by their acceptance angle resulting in a blurred retinal image (Götz, 1965; van Hateren, 1993). Despite the low spatial resolution of the eyes of insects, they are obviously able to accomplish even intricate spatial vision tasks (see above). The low number of retinal input channels reduces the computational load for subsequent information processing tremendously and, thus, may be one reason why insects are so efficient with respect to computational expenditure. (2) As a consequence of the biophysical transduction machinery, the photoreceptors represent a kind of temporal low-pass filter. Owing to adaptive mechanisms, the strength of this temporal blurring depends on the ambient brightness, with the time-constants of blurring reflecting a trade-off between fast transmission and the reliability of the retinal output signals given the stochastic nature of the photons impinging on the photoreceptors (Juusola et al., 1994, 1996; Juusola, 2003).

The photoreceptor output is fed into the neural network of the first visual neuropile, the lamina (Figure 6A). Here, those photoreceptors looking at the same point in visual space converge on common second order neurons (Kirschfeld, 1972), thereby increasing the reliability of signal transmission, especially at low-light intensities (Laughlin, 1994). The photoreceptor signals are further processed in the lamina. (1) They are temporally band-pass filtered, thereby enhancing the representation of contrast changes in the retinal images (Laughlin, 1994; van Hateren, 1997). Owing to the special properties of the synapses between photoreceptors and second order neurons, the signal time course becomes faster and more transient with increasing background intensity (Juusola et al., 1995). Given the noisiness of the input signals and the limited dynamic range of nerve cells, the overall brightness-dependent spatiotemporal filter properties of the peripheral visual system are thought to maximize the flow of information about natural moving images (van Hateren, 1992). It should be noted that these conclusions are based so far on image sequences resulting from smoothly superimposed rotational and translational movements, without taking the different dynamical properties of image changes during saccades and intersaccades into account. During translational intersaccadic movements, the image dynamics can be expected to depend on the depth structure of the scenery, because the retinal images of distant objects move at lower velocities than those of near objects (Figure 5). (2) Recent evidence based on targeted genetic manipulations of individual cell types in the peripheral visual system of Drosophila indicate, though there are differences in details between studies, that the lamina output is segregated into parallel ON and OFF pathways, signaling either brightness increases or decreases (Joesch et al., 2010; Reiff et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2011). One functional consequence of splitting the visual input into ON and OFF components is to facilitate the biophysical implementation of the mechanism of motion detection at subsequent stages of the visual system. The core of this mechanism is a multiplication-like interaction between neighboring retinal input channels (see below), which gives a positive output for two positive as well as for two negative inputs (Egelhaaf and Borst, 1992, 1993b; Eichner et al., 2011).

Figure 6.

Visual system of the blowfly and neural circuits extracting optic flow information from the retinal image sequences. (A) Schematic of a horizontal section of the fly's brain projected onto a photograph of its head, with the retina and the three main visual neuropiles labeled. (B) Wiring sketch of some LWCs sensitive to different types of horizontal motion in the lobula plate of the blowfly. The HSE cells, one type of HS cells, which respond best to coherent wide-field motion, and the FD1 cells, a special type of FD cells, which are most sensitive to the motion of objects, are highlighted. (C) Structure of an FD1 cell with its dendritic tree residing in the lobula plate. The cell is shown in a whole-mount preparation after it has been injected with the fluorescent dye Lucifer Yellow. (D) Dependence of the normalized response amplitude of an HSE and a FD1 cell on the angular horizontal extent of a moving pattern. The responses are based on computer simulations of a circuit model [as shown in (B)]; the model responses mimic the physiologically determined responses (Data from Hennig and Egelhaaf, 2012).

Local motion computation

A lot is known, especially in flies, about the computations underlying motion vision. The available evidence on bees suggests that motion information is processed in their visual system according to similar principles. Local motion detection is assumed to be accomplished in the second visual neuropile, the medulla (Figure 6A). Motion-specific responses have been found in the two most proximal layers of the medulla. Most motion sensitive medulla neurons that could be functionally characterized have small receptive fields, as is expected from neurons involved in local motion detection (review: Strausfeld et al., 2006). As a consequence of the small size of the neurons in this brain area and the difficulty of recording their activity, conclusions concerning the cellular mechanisms underlying motion detection are still tentative. A lot of progress is currently being made by combining the sophisticated repertoire of genetic and molecular approaches in Drosophila with electrophysiological and imaging techniques to identify the different components of the neural circuits underlying motion detection (Rister et al., 2007; Joesch et al., 2008, 2010; Katsov and Clandinin, 2008; Borst, 2009; Reiff et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2011; Schnell et al., 2012).

A large number of features of motion detection can be accounted for by a computational model, the so-called correlation-type motion detector. In its simplest form, a local motion detector is composed of two mirror-symmetrical subunits. In each subunit, the signals of adjacent light-sensitive cells receiving the filtered brightness signals from neighboring points in visual space are multiplied after one of them has been delayed. The final detector response is obtained by subtracting the outputs of two such subunits with opposite preferred directions, thereby considerably enhancing the direction selectivity of the motion detection circuit. Each motion detector reacts with a positive signal to motion in a given direction and with a negative signal to motion in the opposite direction (reviews: Reichardt, 1961; Borst and Egelhaaf, 1989; Egelhaaf and Borst, 1993b). Various elaborations of this basic motion detection scheme have been proposed to account for the responses of insect motion-sensitive neurons under a wide range of stimulus conditions including even natural optic flow as experienced under free-flight conditions (see e.g., Borst et al., 2003; Lindemann et al., 2005; Brinkworth et al., 2009).

Extraction of optic flow information

Since the optic flow as induced during locomotion has a global structure, it cannot be represented in any specific way by local mechanisms alone. Rather, local motion measurements from large parts of the visual field need to be combined. This is accomplished in the third visual neuropile, the lobula complex, by directionally selective wide-field neurons (Figure 6) in all insect species analysed so far. Independent of the species under investigation, these neurons will here be collectively referred to as LWCs (lobula complex wide-field cells). LWCs have been investigated in particular detail in flies, where they reside in the distinct posterior part of the lobula complex; they are, therefore, often termed lobula plate tangential cells (LPTCs). In bees, the lobula complex is undivided; however, bees have very similar motion-sensitive wide-field neurons to those characterized in the lobula plate of flies (DeVoe et al., 1982; Ibbotson, 1991). Most LWCs spatially pool the outputs of many retinotopically arranged local motion-sensitive neurons on their large dendrites and, accordingly, have large receptive fields. These local motion-sensitive neurons are thought to correspond to the local motion detectors, as described above. LWCs are excited by motion in their preferred direction and are inhibited by motion in the opposite direction (reviews: Hausen and Egelhaaf, 1989; Krapp, 2000; Borst and Haag, 2002; Egelhaaf et al., 2002; Egelhaaf, 2006; Taylor and Krapp, 2008; Borst et al., 2010).

For fly LWCs, the local motion-sensitive elements that synapse onto their dendrites have been concluded to differ in their preferred direction of motion. As a consequence, local preferred directions of LWCs change gradually over their receptive field and it has been suggested that they coincide with the directions of the velocity vectors characterizing the flow fields that are induced during certain types of self-motion (Hausen, 1982; Krapp et al., 1998, 2001; Petrowitz et al., 2000; Taylor and Krapp, 2008).

Despite the characteristic patterns of preferred directions in the receptive fields of LWCs, dendritic pooling of motion input is not sufficient to obtain specific responses during particular types of self-motion. Network interactions, mediated by both electrical and chemical synapses, between LWCs within one brain hemisphere and between both halves of the visual system are important for shaping their specific sensitivities for optic flow (Figure 6B; reviews: Borst and Haag, 2002; Egelhaaf et al., 2002; Egelhaaf, 2006; Borst et al., 2010). To enhance the specificity of LWCs for particular global optic flow patterns, interactions between both visual hemispheres are particularly relevant. The optic flow, for instance, across both eyes during forward translation is directed backwards. In contrast, during a pure rotation about the animal's vertical axis, optic flow is directed backwards across one eye, but forwards across the other eye. Thus, translational and rotational optic flow can, at least in principle, be distinguished if motion from both eyes is taken into account (Hausen, 1982; Egelhaaf et al., 1993; Horstmann et al., 2000; Farrow et al., 2003, 2006; Karmeier et al., 2003; Borst and Weber, 2011; Hennig et al., 2011). Other LWCs of blowflies, the figure detection (FD) cells, respond best to the motion of objects rather than to global optic flow patterns. This object sensitivity could be shown for one prominent element of this group of cells to be a consequence of inhibitory synaptic interactions with other LWCs (Figures 6B–D) (Egelhaaf, 1985b; Warzecha et al., 1993; Kimmerle and Egelhaaf, 2000a,b; Hennig et al., 2008, 2011; Hennig and Egelhaaf, 2012; Liang et al., 2012). FD cells are thought to play a prominent role in detecting stationary objects in the environment, such as landing sites that are distinguished from their background by motion, and also other visual cues. Other LWCs found in various fly species respond to much smaller objects than do FD cells. These cells were interpreted as being involved in detecting and pursuing prey and/or mates (Olberg, 1981, 1986; Gilbert and Strausfeld, 1991; Nordström et al., 2006; Nordström and O'Carroll, 2006; Barnett et al., 2007; Geurten et al., 2007; Trischler et al., 2007) and it is suggested they owe their exquisite sensitivity for extremely small targets to a variety of local and global synaptic interactions (Nordström, 2012).

Although the synaptic interactions between LWCs may increase their specificity for particular types of optic flow and stimulus sizes, this specificity is usually far from being perfect, and most neurons still respond to a wide range of “non-optimal” stimuli indicating that behaviorally relevant motion information is encoded by the activity profile of populations of LWCs rather than by the responses of individual cells.

Despite their specific differences, LWCs have general properties which may be functionally relevant in the context of spatial vision.

Velocity dependence: LWCs do not operate like odometers: their mean responses increase with increasing velocity, reach a maximum, and then decrease again. Hence, their response does not reflect pattern velocity unambiguously. This ambiguity is even more complex, since the location of the velocity maximum depends on the textural properties of the moving stimulus pattern. If the spatial frequency of a drifting sine-wave grating is shifted to lower values, the velocity optimum shifts to higher values. In terms of the correlation model of motion detection, the location of the temporal frequency optimum is determined by the time constant of the delay filters in the local motion detectors (review: Egelhaaf and Borst, 1993b). The pattern dependence of velocity tuning is reduced if the stimulus pattern consists of a broad range of spatial frequencies, as is characteristic of natural scenes (Dror et al., 2001; Straw et al., 2008). Despite these ambiguities, flies and bees appear to regulate their intersaccadic translation velocity during free-flight to keep the retinal velocities in that part of the operating range of the motion detection system in which responses increase monotonically with retinal velocities (Baird et al., 2010; Portelli et al., 2011; Kern et al., 2012).

Time course of motion responses: The representation of image velocity becomes even more complex if we take time-varying pattern velocities into account, as are characteristic of behavioral situations. The time course of LWC responses is roughly proportional to pattern velocity only as long as the velocity changes are small (Egelhaaf and Reichardt, 1987; Haag and Borst, 1997, 1998). However, as a consequence of the computational structure of local motion detectors, LWC responses do not only depend on pattern velocity, but also on higher-order temporal derivatives (Egelhaaf and Reichardt, 1987). This is reflected, for instance, in the response transients to sudden changes in pattern velocity (Egelhaaf and Borst, 1989; Egelhaaf and Warzecha, 1998; Warzecha et al., 1998). The rapid saccadic turns characterizing insect free-flight probably lead to the most transient retinal image displacements that occur under natural conditions. The retinal peak velocities attained during saccades of up to several thousands of degrees per second are far beyond the velocity optima determined even for transient conditions (Maddess and Laughlin, 1985; Warzecha et al., 1999). Nonetheless, saccade direction can be encoded by LWCs by transient responses with corresponding signs. However, this is the case only as long as the cell is not excited by translational optic flow during intersaccades, for example, when the animal flies close to environmental structures. In this case, the cell may be depolarized more strongly by the translational optic flow than by a preferred-direction saccade, even though the translational velocities are much smaller than the velocities evoked by the saccades (Kern et al., 2005; van Hateren et al., 2005).

Motion adaptation: Motion vision systems operate under a variety of dynamical conditions. Accordingly, several response features of LWCs have been shown to depend on stimulus history in a characteristic way. A number of mechanisms are involved in the corresponding changes in the visual motion pathway. Some of them operate locally and, thus, presynaptic to the LWCs; they are, to some extent, independent of the direction of motion. Other mechanisms originate after spatial pooling of local motion signals at the level of LWCs, making them dependent on the direction of motion (reviews: Clifford and Ibbotson, 2003; Egelhaaf, 2006; Kurtz, 2009). All these processes are usually regarded as adaptive, although their functional significance is still not entirely clear. Several non-exclusive possibilities have been proposed, such as adjusting the dynamic range of motion sensitivity to the prevailing stimulus dynamics (Brenner et al., 2000a; Fairhall et al., 2001), saving energy by adjusting the neural response amplitudes without affecting the overall information that is conveyed (Heitwerth et al., 2005), and increasing the sensitivity to changes in stimulus parameters resulting from environmental discontinuities (Maddess and Laughlin, 1985; Liang et al., 2008, 2011; Kurtz et al., 2009).

Gain control by dendritic integration of antagonistic motion input: Dendritic integration of signals from local motion-sensitive elements by LWCs is a highly non-linear process. When the signals of an increasing number of input elements are pooled, saturation non-linearities make the response largely independent of pattern size. However, the response saturates at different levels for different velocities. Hence, LWC responses are almost invariant against changes in pattern size, while they still depend on velocity. This gain control can be explained on the basis of the passive membrane properties of LWCs and the antagonistic nature of their motion input. Even motion in the preferred direction activates both types of the two mirror-symmetrical subunits of the motion detector, for instance, excitatory and inhibitory inputs of LWCs, though to a different extent, depending on the velocity of motion. As a consequence, the saturation levels reached by the membrane potential of an LWC with increasing numbers of activated input elements are different for different velocities (Hausen, 1982; Egelhaaf, 1985a; Borst et al., 1995; Single et al., 1997).

Pattern dependence: The responses of the local input elements of LWCs are temporally modulated even during pattern motion at a constant velocity owing to their small receptive fields. These modulations are the consequence of the texture of the environment. Since the signals of neighboring input elements are phase-shifted with respect to each other, their pooling by the dendrites of LWCs reduces mainly those pattern-dependent response modulations that originate from the high spatial frequencies of the stimulus pattern. The pattern-dependent response modulations decrease with the increasing size of the receptive field (Figure 7) depending, to some extent, on its aspect ratio (Egelhaaf et al., 1989; Single and Borst, 1998; Dror et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2011; O'Carroll et al., 2011; Hennig and Egelhaaf, 2012; Kurtz, 2012). From the perspective of velocity coding, the pattern-dependent response modulations have been viewed as “pattern noise” because they deteriorate the quality of the neural representation of pattern velocity (Dror et al., 2001; O'Carroll et al., 2011). Alternatively, these pattern-dependent modulations may be functionally relevant, as they reflect the textural properties of the surroundings (Meyer et al., 2011; Hennig and Egelhaaf, 2012). We will argue below that the latter interpretation might be relevant especially during translatory locomotion during intersaccadic intervals.

Figure 7.

Pattern-dependent response modulations of modeled arrays of movement detectors. (A) Panoramic high dynamic range image of a forest scene (rescaled in contrast for printing purposes). (B) Logarithmic color-coded standard deviation describing the mean pattern-dependent modulations for one-dimensional receptive fields differing in the elevation of receptor position and azimuthal receptive field size. Pattern-dependent modulations decrease with horizontal receptive field extent. Modulation amplitude depends on the contrast distribution of the input image, as can be seen when comparing pattern-dependent modulation amplitudes corresponding to the upper (trees) and lower part (ground) of the input image. (C) Time-dependent response of an array of movement detectors with an estimated HSE cell receptive field. Inset: Weight field of the spatial sensitivity distribution of a HSE cell. The brighter the gray level, the larger the local sensitivity. The frontal equatorial viewing direction is at 0° azimuth and 0° elevation. Image motion was performed for 12 s in the preferred direction of the model cell at an angular velocity of 60°/s (Data from Meyer et al., 2011).

Behavioral significance of optic flow neurons

What is the functional significance of the response characteristics of the motion sensitive and directionally selective LWCs described above? Two related and, to some extent, interdependent views are prevalent in the literature: (1) LWCs are conventionally conceived as self-motion sensors and, in particular, rotation detectors, in other words, neural elements sensing deviations of the animal from its normal attitude and/or flight course. (2) It is often implicitly assumed that the motion detection system should produce responses that come close to a veridical representation of the retinal velocities. Deviation from this velocity representation, such as the ambiguities in the responses resulting from the pattern properties of the stimulus and the fact that the response first increases with increasing velocity, but then decreases again beyond some velocity level (see above), are then regarded as deficiencies of an imperfect biological mechanism. However, it is becoming increasingly obvious from recent research that both views need to be qualified given the peculiar spatiotemporal characteristics of the retinal image flow resulting from the active vision strategies of insects. Moreover, constraints imposed by the timescale of behavior need to be taken into account when interpreting the functional significance of LWCs.

A role of LWCs in mediating compensatory optomotor turning responses

LWCs are commonly thought to mediate compensatory optomotor turning responses of the entire body as well as the head. The strongest, though not very specific, evidence is based on the fact that many characteristics of the behavioral responses correlate well with the response characteristics of LWCs: they show similar velocity sensitivity, and the local preferred directions of various LWCs appear to match with rotational optic flow fields and, thus, were interpreted as an adaption to detect rotational self-motion of the animal around different axes (Krapp and Hengstenberg, 1996; Krapp et al., 1998, 2001; Krapp, 2000; Elyada et al., 2009).

Optomotor following of the entire animal is often analysed in tethered flight both under open- and closed-loop conditions: Here, the fly generates turning responses of the head and the body and follows the moving pattern. This response is usually interpreted to reflexively stabilize the retinal images by minimizing the retinal velocities, for instance, resulting from external and/or internal disturbances (Hausen and Egelhaaf, 1989; Krapp, 2000; Borst and Haag, 2002; Egelhaaf, 2006; Taylor and Krapp, 2008; Borst et al., 2010). However, only rotational optic flow can be eliminated in this way, and the retinal images cannot be stabilized entirely during flight, because the animal needs to translate if it wants to move from one place to another.

A general feature of compensatory optomotor responses is that they are relatively slow. Their response dynamics differ considerably from the much faster object-induced fixation responses (Egelhaaf, 1987, 1989; Warzecha and Egelhaaf, 1996; Duistermars et al., 2007; Rosner et al., 2009). What is the functional significance of such slow compensatory optomotor responses under natural behavioral conditions? Since intersaccadic gaze stabilization is very fast, it is hardly conceivable that it could be controlled by optomotor feedback. Optomotor feedback can play a role only at a much slower timescale, for instance, to compensate for steady asymmetries at the level of the sensory input (e.g., dirt on one eye or internal gain differences) or the motor output (e.g., worn-out wings). Evidence for this comes from experiments where asymmetries were introduced to the visual system by occluding one of the eyes (Kern et al., 2000, in preparation). These behavioral results indicate that LWCs may play a role in mediating compensatory responses of the animal to slow unintended deviations from course, after their output signals are considerably low-pass filtered. So far, it is not clear where in the nervous system downstream of the lobula complex and by what mechanisms this filtering is accomplished.

In addition to the body, the head of flies and bees also performs compensatory optomotor responses in both tethered and free-flight. Compensatory head movements are most prominent during roll rotations of the body as are generated during banked saccadic turns and during sideways translations (Hengstenberg, 1993; van Hateren and Schilstra, 1999; Boeddeker and Hemmi, 2010; Boeddeker et al., 2010; Geurten et al., 2010). Fast gaze stabilization in flies is mainly achieved by mechanosensory input from halteres that act as gyroscopes (Sandeman and Markl, 1980). However, some LWCs have a rather direct impact on head muscles and, thus, on mediating head rotations (Milde et al., 1987, 1995; Gronenberg and Strausfeld, 1990; Gronenberg et al., 1995; Huston and Krapp, 2008, 2009). Bees, like most other insects, lack specialized inertial sensors like halteres. Nonetheless, they also show an optomotor reflex that uses visual motion to stabilize the head with respect to the visual environment under free-flight conditions at retinal velocities of up to 300°/s (Boeddeker and Hemmi, 2010). Experiments on fruit flies provide a similar picture: whereas the visual system is tuned to relatively slow rotation, the haltere-mediated response to mechanical oscillation increases with rising angular velocity (Hengstenberg, 1993; Sherman and Dickinson, 2003, 2004).

In conclusion, LWCs are likely to mediate optomotor responses on a relatively slow timescale, and might thus help compensating rotational optic flow arising from internal asymmetries of the animal. Given the extremely rapid timescale on which gaze direction is stabilized during saccadic flight maneuvres and the response latencies of visually mediated head responses, the functional role of LWCs for compensatory head rotations under free-flight conditions is still not entirely clear.

A role of LWCs in gathering information about the environment during intersaccadic intervals

The time that flies and bees keep their gaze straight amounts to more than 80% of the overall flight-time (Schilstra and van Hateren, 1999; van Hateren and Schilstra, 1999; Boeddeker et al., 2005, 2010; Braun et al., 2010, 2012; Geurten et al., 2010; van Breugel and Dickinson, 2012). Hence, rotations are squeezed into relatively short and rapid saccadic turns. This flight and gaze strategy has been interpreted as a way to facilitate gathering environmental information that is contained in the retinal image flow during translatory self-motion (see above). Therefore, motion-sensitive neurons appear to be predestined to provide environmental information during intersaccadic intervals.

This suggestion is plausible, because the specificity of most LWCs for rotational optic flow is not exclusive and they also respond strongly to translational optic flow (Hausen, 1982; Horstmann et al., 2000; Karmeier et al., 2003, 2006; Taylor and Krapp, 2008). Moreover, the most prominent rotations performed by insects in free-flight, the saccadic turns, lead to angular velocities that are much beyond the monotonic operating range of the motion detection system (see above); rather the monotonic operating range roughly matches the intersaccadic translational velocities in those retinal regions that are probably involved in controlling the translation velocity of the animal (Kern et al., 2012).

As has been stressed above, LWCs are not veridical sensors of velocity and, thus, do not provide unambiguous information about self-motion. This is particularly obvious for the translatory movements during intersaccadic intervals, because here, retinal velocities do not only depend on the velocity of locomotion, but also on the three-dimensional layout of the environment. This dependency is reflected in the responses of HS cells; a group of three fly LWCs with a main preferred direction from the front to the back in the visual field of one eye. These neurons depolarize if environmental structures are sufficiently close, especially during translatory self-motion with a strong sideways component (Figure 8) (Boeddeker et al., 2005; Kern et al., 2005; Lindemann et al., 2005; Liang et al., 2012). Similar results were obtained in further LWCs during translatory movements in other directions (Karmeier et al., 2006). However, spatial information is only provided by LWCs if rotational movements are largely eliminated during the intersaccadic intervals, emphasizing the importance of the active saccadic flight and gaze strategy in the context of spatial vision (Kern et al., 2006). The responses to objects nearby are even more augmented by adaptation mechanisms, which depend on stimulus history, and, thus, on the properties of previous flight sequences (Liang et al., 2008, 2011).

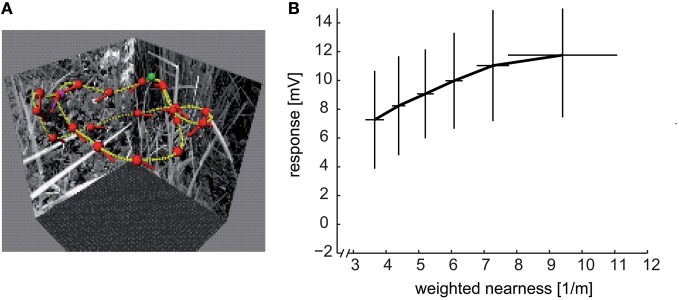

Figure 8.

Distance dependence of intersaccadic responses in the HSE cell, a prominent LWC in the blowfly lobula plate. (A) Sample flight trajectory of a blowfly in a cubic arena used for the reconstruction of optic flow. The track of the fly is indicated by the yellow lines; red dots and short dashes indicate the position of the fly's head and its orientation, respectively; green and violet dots indicate the start and end of the trajectory, respectively. (B) Average intersaccadic responses of HSE cell recordings from three different flight trajectories plotted versus the corresponding average weighted nearness. The responses were sorted by increasing nearness and then attributed to six groups. The vertical and horizontal lines show the standard deviations of responses and nearness, respectively, across the data values within one group. The intersaccadic responses were related to the nearness of the fly to the respective arena walls (nearness = 1/distance), weighted by the HSE cell's spatial sensitivity distribution (see inset of Figure 7C). The intersaccadic responses increase with increasing nearness to the walls of the flight arena (Data from Liang et al., 2012).

What is the range within which spatial information is encoded in this way? Under spatially constrained conditions where the flies flew at translational velocities of only slightly more than 0.5 metres per second, the spatial range within which significant distance dependent intersaccadic responses are evoked amounts to approximately two metres (Kern et al., 2005; Liang et al., 2012). Since a given retinal velocity is determined in a reciprocal way by distance and velocity of self-motion, respectively, the spatial range that is represented by LWCs can be expected to increase with increasing translational velocity. In other words, the behaviorally relevant spatial range can be assumed to scale with locomotion velocity. From an ecological point of view, this consequence of the closed-loop nature of vision is economical and efficient, since the behaviorally relevant spatial depth range increases during fast self-motion. A fast moving animal can thus initiate an avoidance maneuvre earlier and at a greater distance from an obstacle than when moving slowly.

Recently, we found that the responses of bee LWCs to visual stimuli as experienced during navigation flights in the vicinity of an invisible goal also strongly depend on the spatial layout of the environment. The spatial landmark constellation that guides the bees to their goal leads to a characteristic time-dependent response profile in LWCs during the intersaccadic intervals of navigation flights (Mertes et al. in preparation).

The responses of LWCs of flies and bees do not only depend on the retinal velocities, but are also sensitive to pattern properties (Figure 7; see above). Although the pattern-dependent modulations in the neural responses have been conventionally viewed as detrimental to the velocity signal, they may reflect functionally relevant information about the environment (Meyer et al., 2011; Hennig and Egelhaaf, 2012). This may be the case especially during intersaccadic translatory movements: since the retinal velocity scales with distance, an object nearby will lead to larger intersaccadic depolarization than a more distant one. Assuming that objects nearby are especially functionally relevant, object detection via optic flow automatically weighs objects according to their distance and, thus, their functional relevance. In other words, cluttered spatial scenery is segmented in this way, without much computational expenditure, into nearby and distant objects.