Abstract

Umbilical endometrioma is a rare condition, with an estimated incidence of 0.5%–1% in all patients with endometrial ectopia. Spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis is an even rarer and more unusual condition with unclear pathogenetic mechanisms. A 44-year-old parous woman presented with an umbilical skin lesion, and no history of bleeding from the umbilical mass or swelling in the umbilical area. The initial clinical diagnosis was granuloma, and excision was planned. Pathology examination revealed endometrial glands with mucinous-type metaplasia surrounded by a disintegrating mantle of endometrial stroma. Clinical examination and magnetic resonance imaging did not reveal pelvic endometriosis lesions, and given that the umbilical endometrioma was totally excised, no further treatment with hormonal therapy was proposed for the patient. Three years after excision, she was free of disease and no recurrence has been observed. Complete excision and histology is highly recommended for obtaining a definitive diagnosis and optimal treatment in spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis.

Keywords: endometriosis, primary endometrioma, umbilical endometrioma

Introduction

Endometriosis, a term first used by Sampson, is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus.1 This ectopic finding affects 7%–10% of women of reproductive age and commonly occurs in the pelvic organs, presenting with dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, pelvic pain, and infertility.1,2 Furthermore, ectopic endometrium occurs in the abdominal wall in 0.03%–1.08% of women with anamnesis of obstetric or gynecologic procedures.1 However, spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis is any ectopic endometrium found superficial to the peritoneum with no previous scar (iatrogenic or not).

An umbilical endometrioma is a rare condition, with an estimated incidence of 0.5%–1% in all patients with endometrial ectopia.2 It can occur following laparoscopic or other surgical procedures involving the umbilicus. Primary umbilical endometriosis is an even rarer and more unusual condition with unclear pathogenetic mechanisms.1–4 This is a report of a rare case of primary umbilical spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis.

Case report

A 44-year-old parous woman presented to the outpatient clinic of our department with an umbilical skin lesion accompanied by pain one week before her menses every month during the previous year. The pain in the umbilical area continued for the entire duration of her period. She also reported that this umbilical mass had first appeared 5–6 years previously and had enlarged during the previous year.

The patient had regular and painless menstrual periods and she had experienced two spontaneous vaginal deliveries. She had no history of bleeding from the umbilical mass or swelling in the umbilical area, abdominal pain, dyspareunia, or infertility. Her medical history was not significant, with no history of abdominal surgery.

Clinical examination revealed a skin-colored, mobile umbilical nodule measuring approximately 0.6 × 0.6 cm. The initial clinical diagnosis was granuloma. There was no strong diagnostic evidence of abdominal wall endometriosis, and hence the patient did not report any association between her menstrual period and bleeding or swelling of this umbilical lesion.

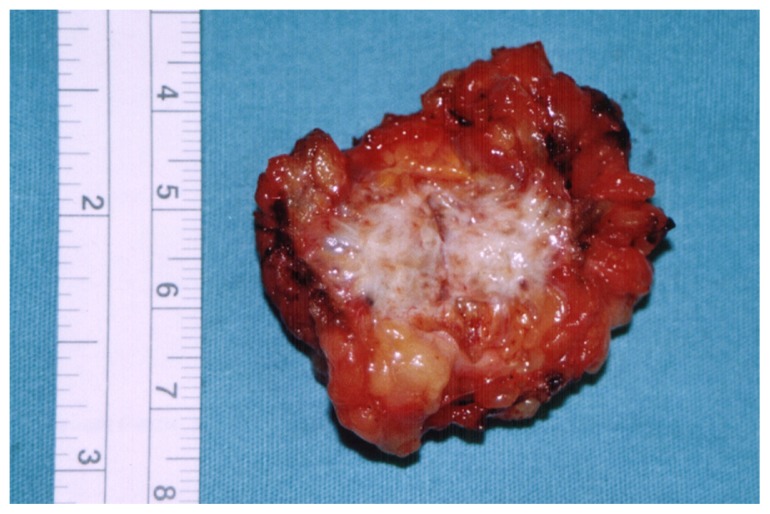

The patient was offered surgical management and excision was planned. During the operation, the mass was found approximately 10 mm below the skin surface and was excised with a healthy margin (excision area 2 × 2 cm, Figure 1). Surgical pathology revealed a 2.0 × 2.0 × 3.0 cm area of endometriosis with negative margins at the umbilicus. Histopathologic features of cutaneous endometriosis and endometrial glands with mucinous-type metaplasia in a fibrous eosinophilic stroma were noted within the dermis. Additionally, small diffuse foci of stromal lymphovascular tissue consistent with mild inflammation and plasma cells were present, suggesting endometritis. No epithelial atypia was seen and the excision appeared complete.

Figure 1.

Primary Umbilical Endometrioma: surgical excised tissue.

The risk of recurrence and scar endometriosis were explained to the patient. When followed up 4 weeks after surgery she was found to be asymptomatic, with the appearance of the umbilicus being satisfactory. The patient was referred to the outpatient clinic of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology for evaluation and a potential further consultation. However, clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations did not reveal pelvic endometriosis lesions, and given that the umbilical endometrioma was totally excised, no further treatment with hormonal therapy was proposed for the patient. Three years after excision, the patient remains free of disease and no recurrence has been observed.

Discussion

Endometriosis due to the presence of ectopic tissue can be found in almost any organ and cavity of the female body, including the lungs, bowel, ureter, and brain, but the most frequent location is the abdominal wall.1–6 Abdominal wall endometriosis is commonly associated with abdominal surgical scars, especially those associated with cesarean section, laparoscopy, and amniocentesis. However, the definition of abdominal wall endometriosis includes lesions that are not due to previous surgical procedures, and such cases are referred to as spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis.1

No large prospective or retrospective studies have investigated spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis. A literature review by Horton et al revealed that abdominal wall endometriosis was associated with surgical scars in only 48% of 445 patients with the condition. Although cesarean section is associated with abdominal wall endometriosis in 0.03%–1.7% of all cases, spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis is less common than scar-related endometriosis, and according to Horton et al, represents only 20% of all cases.1,5 However, the incidence of spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis in the literature reportedly lies in the range of 0%–38%.1,6

The most common locations of spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis appear to be the umbilicus and groin.1,2 The first description of an umbilical endometrioma is accredited to Villar in 1886, and since then this condition has been referred to as a Villar’s nodule. Umbilical endometriosis is a rare condition accounting for up to 30%–40% of all cutaneous endometriosis cases, having an estimated incidence of 0.5%–1% in all cases of endometrial ectopia.3,6,7 According to the literature, a total of only 109 cases of umbilical endometriosis has been described, but most reportedly developed secondary to surgical scars.2,7

A primary umbilical endometriotic lesion without any surgical history is an even rarer condition, with an estimated overall incidence of less than 0.5%–1% among all endometriosis cases.7 To our knowledge, there is not any systematic literature review on published cohorts of patients or case reports having primary umbilical endometrioma. Furthermore, primary umbilical endometriosis is a condition of specific interest to the general surgeon, because diagnosing any extrapelvic spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis can be difficult in patients without any symptoms associated with menstruation.1,6,7

There has been considerable speculation regarding the pathogenesis of endometriosis, and several theories have been proposed.1–3,5,6 In 1953, Latcher classified all theories into three main categories, ie, the embryonic rest theory, the coelomic metaplasia theory, and the migratory pathogenesis theory.2 The embryonic rest theory attributes endometriosis adjoining the pelvic viscera to a specific stimulus to a Mullerian origin cell nest.1–3,5,6

In 1927, Sampson first described the implantation or retrograde menstruation theory, which states that during menses, refluxed endometrial cells escape from the fallopian tubes and implant on the surrounding pelvic structures.1–3,5,6 The direct transplantation theory can explain the endometriosis occurring on surgical scars, but does not explain the rare locations of endometriomas in distant organs, such as the brain or lungs. This prompted Halban to develop the dissemination theory of vascular migration of endometrial cells to ectopic sites, which explains the dispersion of endometrial tissue by direct extension via vascular or lymphatic channels and also in surgical procedures.2,5

The second theory of coelomic metaplasia or induction theory is based on embryologic studies, and involves metaplasia of cells in the abdominal wall into endometrial cells, which also suggests that sloughed endometrium produces substances that form endometriosis. This metaplasia may be induced by hormonal manipulation, inflammation, or trauma.1,3,5 The most recent theory of cellular immunity proposes cellular proliferation of ectopic endometrial cells. The actual mechanism remains unclear, but none of the suggested theories should be excluded until convincing experimental data are obtained. As a result, some investigators advocate a combination of the aforementioned theories.3,6

Furthermore, in cases of spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis (as in the case report presented herein), the implantation theory, the direct transplantation theory, and the induction theory seem incapable of explaining the pathogenesis, while the dissemination theory through lymphatic or vascular spread can explain the occurrence of endometriosis at distant locations. Moreover, in the development of umbilical endometriosis, some authors hypothesize that the umbilicus acts as a physiologic scar with a predilection for endometrial tissue.3

Extragenital endometriosis has various presentations and remains a difficult condition to diagnose and treat. In abdominal wall endometriosis, the chief symptom is usually a mass at the site of maximum tenderness, which varies in size following the menstrual cycle, while the typical characteristic is cyclic pain associated with menses.1,3 There are reports that the pain can be constantly present without any association with the menstrual cycle, but this is generally regarded as atypical, which may explain why abdominal wall endometriosis is often misdiagnosed clinically. In such atypical cases, and especially in cases of spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis, symptoms and signs may occur singly, which always hinders an accurate diagnosis. In published series, the reported preoperative diagnosis rate has varied between 20% and 50%.4 This diagnostic failure could be due to general surgeons, who often make the diagnosis, not being sufficiently familiar with abdominal wall endometriosis. Another possible explanation is the atypical presentation of the disease along with the possible differential diagnoses, including lipoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, primary or metastatic cancer, cysts, and inguinal or incisional hernia.1–4

Clinical diagnosis is often difficult in cases of umbilical endometriosis. Patients suffering from this condition are usually of reproductive age and often present with an umbilical mass associated with swelling, pain, discharge, or cyclical bleeding.2 The umbilical nodule has been described as being flesh-colored, brownish, dark-bluish, or simply a subcutaneous mass, with a size that typically varies from 0.5 cm to several centimeters, but can be enormous.1,3,4 There may be associated symptoms of coexistent pelvic endometriosis, although the incidence of pelvic disease in abdominal wall endometriosis is within the same range as the general population (8%–15%).2,5 Due to the variable macroscopic appearance of umbilical endometriomas, these lesions can initially be confused with malignant tumors, such as melanoma. Nevertheless, any condition presenting with a subcutaneous mass or discoloration of umbilical skin should be considered, including pyogenic granuloma, nodular melanoma, primary or metastatic adenocarcinoma, hernia, residual embryonic tissue, and cutaneous endosalpingosis.1–3

While the diagnosis is primarily performed clinically, diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, computed tomography, and MRI have also been used. Ultrasound is useful for determining whether the mass is cystic or solid, but it is not specific for abdominal wall endometriosis.1,2 Computed tomography and MRI can be useful for showing the extent of the abdominal wall endometriosis, and usually show a solid well circumscribed mass, that appears homogeneously hyperintense in T1-weighted MRI sequences. MRI also has the advantage over laparoscopy in its ability to evaluate pelvic and extraperitoneal disease.1,2 Fine-needle aspiration is generally inconclusive, although it may be of some value in cases of scar endometriomas.1,4

According to Catalina-Fernandez et al, dermoscopy can be helpful in cases of cutaneous or subcutaneous endometriosis, with cytologic smears revealing high cellularity with hemosiderin-laden macrophages and sheets of stromal and epithelial cells on a hemorrhagic background.3 The histologic diagnosis of endometrioma requires two of the three following features: endometrial-like glands, endometrial stroma, or hemosiderin pigment.1

The preferred treatment in all cases of abdominal wall endometriosis is wide local excision of the mass, while some investigators propose the addition of hormonal therapy whenever severe pelvic disease is assumed or demonstrably present.1–4 Therefore, surgical resection of an umbilical endometrioma with safety and clear margins is the treatment of choice, and offers the highest probability of both a definitive diagnosis and a favorable outcome. Preservation of the umbilicus is preferred, but if the umbilicus has to be completely removed in order to achieve radical excision, certain methods can provide adequate reconstruction.3 Complete excision of the umbilical lesion may necessitate partial resection of the underlying fascia. This is recommended, because local recurrence is likely if the surgical excision is inadequate. Therefore, wide excision with a margin of at least 1 cm is considered the treatment of choice, even for recurrent lesions.1,3,4 Several authors have advocated the use of hormonal therapy with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog (eg, danazol or progesterone), with the aim of decreasing the size of the mass and facilitating surgery. Furthermore, these hormones can be added to surgical treatment in cases of severe pelvic disease.2,4

Medical management cannot be enthusiastically recommended, due to its reported success rate being low, with it offering only temporary alleviation of the symptoms, and serious adverse effects often being followed by recurrence after cessation of drug intake.1,4 It is also known that both abdominal wall and scar endometriosis are less responsive to hormonal therapy.4

Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis is a very rare complication (in 1% of cases).4 Spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis is usually diagnosed by pathology, especially in cases without the typical triad of mass, pain, and cyclic symptomatology, as in the case report presented herein.

Conclusion

Spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis is currently regarded as a rare disease entity accounting for 20% of all cases of abdominal wall endometriosis. However, abdominal wall endometriosis may occur more frequently than is generally assumed, primarily affecting women between 20 and 40 years of age after a cesarean section. Primary umbilical endometriomas are even rarer. Careful history-taking and physical examination are essential to making the correct diagnosis, although this can be difficult in atypical presentations, and so other causes of umbilical lesions should be considered. MRI can aid the diagnosis. Complete excision and histology is highly recommended for obtaining a definitive diagnosis and to rule out malignancy. Radical surgical resection is also a treatment of choice for abdominal wall endometriosis.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Papavramidis ThS, Sapalidis K, Michalopoulos N, et al. Spontaneous abdominal wall endometriosis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:778–781. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavalli VB, Mamdouh MG. Menstruating from the umbilicus as a rare case of primarily umbilical endometriosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9326. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-3-9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatzikokkinou P, Thorfinn J, Angelidis IK, Papa G, Trevisan G. Spontaneous endometriosis in an umbilical skin lesion. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2009;18:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bektas H, Bilsel Y, Sari YS, et al. Abdominal wall endometrioma: a 10-year experience and brief review of the literature. J Surg Res. 2010;164:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horton JD, DeZee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, Wagner M. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyamidis K, Lora V, Kanitakis J. Spontaneous cutaneous umbilical endometriosis: report of a new case with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(7):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuladeepa AV, Prashanth A, Lakshman IK. Villar’s nodule: a rare case report. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2012;6(5):881–883. [Google Scholar]