Abstract

Escitalopram (escitalopram oxalate; Cipralex®, Lexapro®) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) used for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) and anxiety disorder. This drug exerts a highly selective, potent, and dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the human serotonin transport. By inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin into presynaptic nerve endings, this drug enhances the activity of serotonin in the central nervous system. Escitalopram also has allosteric activity. Moreover, the possibility of interacting with other drugs is considered low. This review covers randomized, controlled studies that enrolled adult patients with MDD to evaluate the efficacy of escitalopram based on the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. The results showed that escitalopram was superior to placebo, and nearly equal or superior to other SSRIs (eg, citalopram, paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline) and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (eg, duloxetine, sustained-release venlafaxine). In addition, with long-term administration, escitalopram has shown a preventive effect on MDD relapse and recurrence. Escitalopram also showed favorable tolerability, and associated adverse events were generally mild and temporary. Discontinuation symptoms were milder with escitalopram than with paroxetine. In view of the patient acceptability of escitalopram, based on both a meta-analysis and a pooled analysis, this drug was more favorable than other new antidepressants. The findings indicate that escitalopram achieved high continuity in antidepressant drug therapy.

Keywords: escitalopram, MDD, SSRI, allosteric action, discontinuation symptoms

Introduction

Escitalopram (escitalopram oxalate; Cipralex® [H Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark], Lexapro® [Forest Laboratories, Inc, St Louis, MO]) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that selectively binds to the human serotonin transporter (SERT). This activity inhibits serotonin (5-HT) reuptake and increases the amount of serotonin in synaptic clefts, which results in antidepressant action.

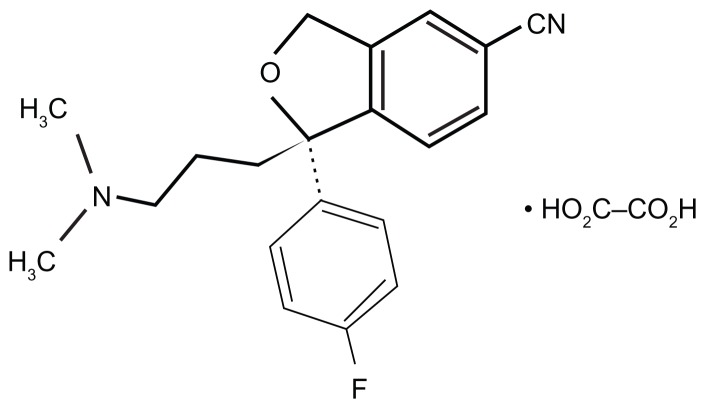

Racemic citalopram (RS-citalopram), an SSRI widely used in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), possesses both an active S-enantiomer and clinically inactive R-enantiomer.1,2 Escitalopram was produced by isolating the active S-enantiomer from RS-citalopram. The structural formula of escitalopram is shown in Figure 1. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that escitalopram inhibits the serotonin transporter protein more potently than citalopram.2–4 For example, in vivo electrophysiological data indicated that escitalopram was four times more potent than citalopram in reducing the firing activity of presumed serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus of rat brain.5 In November 2011, escitalopram was approved in 100 countries in Europe, North America, and other regions. Escitalopram is indicated for generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and MDD.6

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of escitalopram.

Pharmacological profile

Pharmacodynamic profile

Escitalopram has a highly selective, dose-dependent, inhibitory effect on SERT. Its antidepressant action arises from its inhibition of serotonin reuptake into presynaptic nerve ending, which enhances serotonin activity in the central nervous system.1,7 Radioligand binding assays revealed that escitalopram showed particularly high selectivity for SERT compared to citalopram and several other SSRIs.7–9 Escitalopram is “the most typical SSRI” of the SSRI agents, because it has virtually no binding affinity for other transporters.7,9

Escitalopram binds to two different sites of SERTs: the high-affinity binding site (primary site) of SERT, which controls serotonin reuptake in nerve endings; and the low-affinity binding site (allosteric site), which induces structural changes in SERT. The latter (allosteric action) is thought to stabilize and prolong binding of escitalopram to the primary site.3,10–12

Pharmacokinetic profile

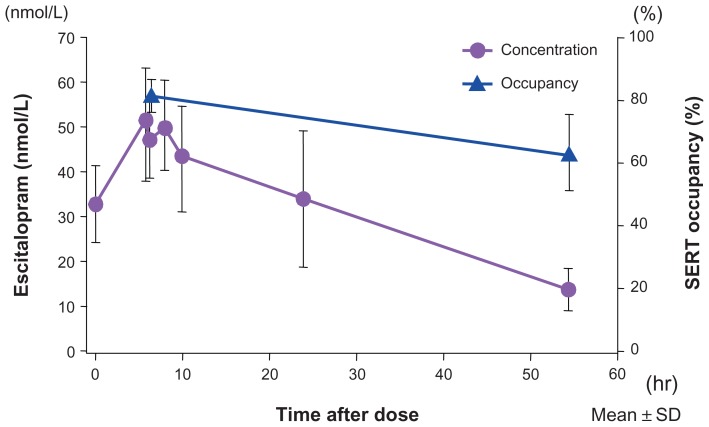

The half-life of receptor occupancy for escitalopram was calculated to be approximately 130 hours, much longer than the half-life of the plasma concentration, which was approximately 30 hours.13 Figure 2 shows the binding occupancy of escitalopram on cerebral SERTs relative to its concentration changes in plasma. An allosteric action may be involved in this prolonged occupancy. Escitalopram is metabolized in the liver, mainly by cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 2C19 and also by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Escitalopram inhibits liver metabolic enzymes, but primarily only CYP2D6,14 with minimal inhibition of the other enzymes; the IC50 for CYP2D6 was higher than its effective blood concentration. In this regard, its interactions with other drugs would presumably be minimal.

Figure 2.

Escitalopram showed 5-HT transporter occupancy that outlived its plasma concentration.

Notes: Escitalopram (10 mg) was administered once daily for 10 consecutive days (the first 5 days are shown) to six healthy men. The 5-HT transporter occupancy rate was determined in the midbrain-hypothalamus region. The 5-HT transporter occupancy rate of escitalopram peaked at 80% and the occupancy half-life was 130 hours.

Copyright © 2007, Springer-Verlag. Adapted with permission from Klein N, Sacher J, Geiss-Granadia T, et al. Higher serotonin transporter occupancy after multiple dose administration of escitalopram compared to citalopram: an [123I]ADAM SPECT study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;191(2):333–339.13

Clinical efficacy

Comparison with placebo

In a placebo-controlled study,15 patients with MDD received escitalopram at a dose of 10 mg/day, and a control group was given placebo. After 8 weeks of therapy, the total Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score changed by −16.3 in the escitalopram group and −13.6 in the placebo group. Thus, escitalopram had significantly greater efficacy than placebo. The total MADRS score of the escitalopram group began to show significant improvement compared to that of the placebo group by the second week of therapy. This demonstrated its fast-acting property. In addition, the remission rate (the percentage of patients with a total MADRS score of 12 or less) was significantly higher in the escitalopram group than in the placebo group. Thus, the initial therapeutic dose (10 mg/day) was demonstrated to be effective. Likewise, in other studies,15,16 escitalopram 10 or 20 mg/day was more effective than placebo in the treatment of MDD. Reduction in MADRS scores, the primary endpoint, were greater with escitalopram than with placebo at the first16 or second15 week and were maintained throughout treatment. Furthermore, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) and Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) scores were reported,15 and support the MADRS score findings: escitalopram produced significant lower CGI-I scores from week 1 and CGI-S scores from week 3 than placebo, and this continued throughout treatment.

Comparison with SSRIs

Six randomized, double-blind, controlled studies16–21 compared escitalopram and citalopram. Escitalopram was administered to patients with MDD for 4–8 weeks at 10–20 mg/day. All six studies16–21 showed that the efficacy of escitalopram was equivalent to or greater than that of citalopram. Details of these studies follow.

In the study by Burke et al16 (n = 491; randomly assigned to placebo, escitalopram, 10 mg/day, 20 mg/day, or citalopram, 40 mg/day), escitalopram (10 mg/day) was at least as effective as citalopram at endpoint. In the study by Lepola et al,17 by week 8, significantly more patients had responded to treatment with escitalopram (n = 155) than with citalopram (n = 160). In the study by Lalit et al,18 response rates at the end of 2 weeks were 58% for escitalopram (10 mg/day) (n = 69) and 49% for citalopram (20 mg/day) (n = 74). Response rates at the end of 4 weeks were 90% for escitalopram (10–20 mg/day) and 86% for citalopram (20–40 mg/day). The remission rates at the end of 4 weeks were 74% for escitalopram and 65% for citalopram. Additionally, there were fewer dropouts and less requirement for dose escalation with escitalopram than with citalopram. In the study of Moore et al,19 MADRS scores decreased more in the escitalopram (n = 138) than in the citalopram (n = 142) arm. There were more treatment responders with escitalopram (76.1%) than with citalopram (61.3%), and adjusted remitter rates were 56.1% and 43.6%, respectively.

In the study by Yevtushenko et al21 (n = 322; randomly assigned to escitalopram, 10 mg/day or citalopram, 10–20 mg/day), at study end, the mean change from baseline in MADRS total score was significantly greater in the escitalopram arm than in the 10 and 20 mg/day citalopram arms. Changes in the CGI-S and CGI-I scores and the rates of response and remission were significantly greater in the escitalopram group compared with those in the citalopram 10 and 20 mg/day groups. On the other hand, in the study by Ou et al20 (n = 240, randomly assigned to escitalopram, 10–20 mg/day or citalopram, 20–40 mg/day), no significant differences were found between the two groups.

The meta-analysis of Montgomery et al,22 comparing escitalopram and citalopram, supported these controlled studies: escitalopram was significantly more effective than citalopram in overall treatment effect, with an estimated mean treatment difference of 1.7 points at week 8 on the MADRS and in responder rate (8.3 percentage points) and remitter rate (17.6 percentage points) analyses, corresponding to number-needed-to-treat (NNT) values of 11.9 for response and 5.7 for remission. The overall odds ratios were 1.44 for response and 1.86 for remission, in favor of escitalopram. However, Trkulja23 reported that MADRS reduction was greater with escitalopram, but 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the mean difference were entirely or largely below two scale points (minimally important difference) and CI around the effect size (ES) was below 0.32 (“small”) at all time points. Risk of response was higher with escitalopram at week 8 (relative risk, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.26) but NNT was 14 (95% CI, 7 to 111). All 95% CIs around the mean difference and ES of CGI-S reduction at week 8 were below 0.32 points and the limit of “small,” respectively. The report concluded that the claims about clinically relevant superiority of escitalopram over citalopram in short- to medium-term treatment of MDD are not supported by evidence.

A long-term, double-blind, controlled study compared paroxetine to escitalopram given for 24 weeks to patients with severe depression.24 In that study, escitalopram at 20 mg/day showed better efficacy than paroxetine at 40 mg/day. The total MADRS score changed by −25.2 in patients given escitalopram and by −23.1 in those given paroxetine. Thus, the outcome was significantly better for the escitalopram group, with an intergroup difference of 2.12. Furthermore, the total Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D17) score changed by −16.9 and −15.0 in the two groups, respectively; again, significantly better outcomes were shown for the escitalopram group than for the paroxetine group. In addition, the remission rate (percentage of patients with a total MADRS score of 12 or lower) was significantly higher (75.0%) in the escitalopram group than in the paroxetine group (66.8%). On the other hand, another study25 that compared variable doses of escitalopram (10–20 mg/day) and paroxetine (20–40 mg/day) revealed equivalent efficacy in the two groups.

In Japan, the superiority of escitalopram to placebo and its noninferiority to paroxetine (20–40 mg/day) were documented in a double-blind, parallel-group study26–28 that compared escitalopram (10 mg/day and 20 mg/day for 8 weeks) to placebo or paroxetine in patients with MDD. Table 1 shows the changes in the total MADRS scores. Based on the P-values, significant improvement was found in both escitalopram groups compared to the placebo group. Furthermore, based on the difference between the combined escitalopram groups and the paroxetine group, the upper limit of the 95% CI was below the noninferiority threshold limit (3.2); this demonstrated the noninferiority of escitalopram to paroxetine. In addition, previous studies have shown that the efficacy of escitalopram was equivalent to that of either fluoxetine or sertraline.29,30

Table 1.

Comparison of changes in total MADRS scores at 8 weeks (last observation carried forward) among patients with MDD treated with escitalopram, paroxetine, or placebo

| Escitalopram 10 mg (n = 120) | Escitalopram 20 mg (n = 119) | Escitalopram combined groups (n = 239) | Paroxetine (n = 121) | Placebo (n = 124) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total scorea | |||||

| At baseline | 29.4 ± 5.8 | 29.8 ± 6.0 | 29.6 ± 5.9 | 29.8 ± 5.9 | 29.0 ± 5.6 |

| At week 8 | 15.6 ± 11.0 | 16.2 ± 10.1 | 15.9 ± 10.5 | 15.6 ± 10.0 | 18.3 ± 10.1 |

| Change | |||||

| At week 8a | −13.7 ± 10.0 | −13.6 ± 8.8 | −13.7 ± 9.4 | −14.2 ± 9.9 | −10.7 ± 9.5 |

| Difference from the placebo groupb | −3.0 | −2.7 | −2.8 | −3.2 | – |

| P-valuec | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.009 | – |

| Difference from the paroxetine groupd | 0.3 (−2.2, 2.8) | 0.6 (−1.7, 3.0) | 0.5 (−1.6, 2.6) | – | – |

| P-valuee | 0.796 | 0.612 | 0.652 | – | – |

Notes: Both escitalopram administration groups showed significant improvement compared to the placebo group. The upper limit of the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the combined escitalopram groups and the paroxetine group was below the noninferiority margin (3.2); this confirmed the noninferiority of escitalopram to paroxetine.

Mean ± SD;

least squares mean;

versus the placebo group (ANCOVA);

least squares mean (two-sided 95% confidence interval);

versus the paroxetine group (ANCOVA). The threshold limit of noninferiority is 3.2. Copyright © 2011, Seiwa Publishers. Adapted with permission from Hirayasu Y. A dose-response and non-inferiority study evaluating the efficacy and safety of escitalopram in patients with major depressive disorder: a placebo- and paroxetine-controlled, double-blind, comparative study. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;14:883–899.26

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; MADRS, Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Comparison with SNRIs

In a double-blind, controlled study31 of escitalopram (10–20 mg/day) versus duloxetine (60 mg/day) for 8 weeks, the changes in the total MADRS scores were −18.0 ± 9.4 and −15.9 ± 10.3, respectively. This result showed that escitalopram was significantly superior to duloxetine. In another long-term, double-blind, controlled study32 of escitalopram (20 mg/day) versus duloxetine (60 mg/day) for 24 weeks, the total MADRS score improved significantly to a greater extent in the escitalopram group than in the duloxetine group at 1 week. This trend persisted until the 16th week. Escitalopram has also shown equivalent or superior efficacy to that of sustained-release venlafaxine (venlafaxine SR).33,34

Long-term administration study

In addition to the two long-term, double-blind studies with paroxetine24 and duloxetine,32 two other long-term studies with escitalopram were carried out in Japan, which involved patients of different age groups. The first study35 involved patients 20–64 years of age (under 65), and the second study36 involved older patients of at least 65 years of age (65 and older). Both studies examined open-label, 52-week administrations of variable doses in outpatients. The remission rate (percentage of patients with a total MADRS score of 10 or lower) increased over the administration period; after 52 weeks, the remission rate was about 70% in both groups. Patients that reached remission by the eighth week were followed, and 20 of 23 of patients in the under-65 age group maintained remission until the end of study. In the 65-and-older age group, the five patients that reached remission by the eighth week also maintained remission.

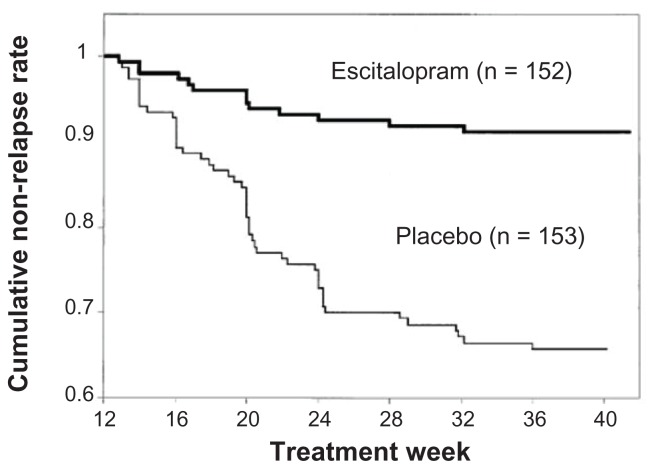

Relapse and recurrence prevention study

An MDD relapse prevention study37 was carried out in another group of patients aged 65 and older. Escitalopram was administered at a dose of 10 or 20 mg/day for 12 weeks. Patients that reached remission (a total MADRS score of 12 or lower) were allocated to receive either escitalopram at 10 or 20 mg/day or placebo. The two groups were followed to determine the relapse rate. The cumulative non-relapse rate remained high in the escitalopram group but decreased over time in the placebo group (Figure 3). At the end of study, relapses were observed in only 9% of the escitalopram group and 33% of the placebo group; thus, the relapse rate was significantly lower in the escitalopram group.

Figure 3.

Changes in the cumulative non-relapse rate.

Notes: Escitalopram exhibits a low relapse rate, demonstrating a significant relapse-preventing effect compared to placebo. Copyright © 2007, Wolters Kluwer Health. Adapted with permission from Gorwood P, Weiller E, Lemming O, Katona C. Escitalopram prevents relapse in older patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(7):581–593.37

An MDD recurrence prevention study38 examined recurrences after 16 weeks of continuous therapy with escitalopram. Patients given escitalopram at a fixed dose of 10 or 20 mg/day were compared to controls given placebo for 52 weeks of maintenance therapy. MDD recurrence was 27% in the escitalopram group – significantly lower than the 65% observed in the placebo group.

Tolerability

Patients with MDD generally exhibited favorable tolerance to escitalopram, regardless of whether they received short-term or long-term therapy. Adverse events were typically mild and temporary.39 The most frequent adverse events that occurred during escitalopram therapy included insomnia, nausea, excessive sweating, fatigue/somnolence, dysspermatism, and decreased libido.40

Comparison with SSRIs or SNRIs

Escitalopram was compared to other SSRIs or SNRIs in a meta-analysis of patient data from 16 double-blind, controlled studies.41 When attention was focused on adverse events that occurred at a frequency of 5% or more, escitalopram showed significantly lower frequencies of diarrhea, dry mouth, and the presence of more than one adverse event compared to the other SSRIs. Escitalopram was also associated with significantly lower frequencies of nausea, insomnia, dry mouth, vertigo, excessive sweating, constipation, and vomiting than the SNRIs.

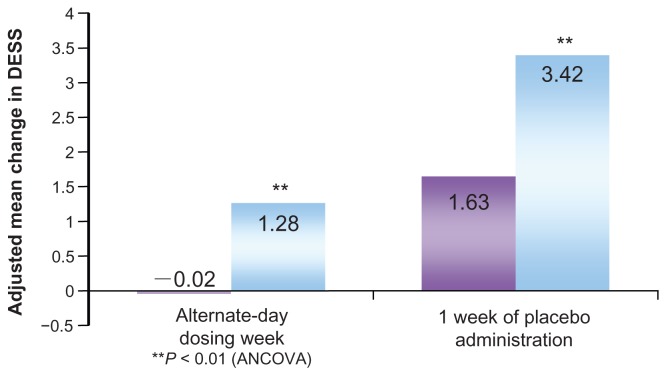

Discontinuation symptoms

Discontinuation symptoms typically occur at the end of treatment with antidepressant drugs. A detailed study26 compared discontinuation symptoms in patients with MDD during the post-therapy observation period after 27 weeks of therapy with escitalopram (20 mg/day) or paroxetine (40 mg/day). Discontinuation symptoms were evaluated in terms of the Discontinuation Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS) score. During the observation period, the drug doses were gradually decreased over 1–3 weeks, followed by 1 week of alternate-day dosing and, subsequently, 1–3 weeks of placebo. The escitalopram group exhibited smaller changes in the total DESS score and significantly less frequent discontinuation symptoms compared to the paroxetine group, both at the end of alternate-day dosing and after 1 week of placebo administration (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Discontinuation Emergent Signs and Symptoms (DESS 47) scores in the post-therapy observation period.

Notes: The change in the total modified DESS 47 score was calculated from the beginning of post-therapy observation to the end of one week with either alternate-day dosing or placebo. The mean scores are indicated in the bars. Scores were −0.02 for the escitalopram group and 1.28 for the paroxetine group. The corresponding values at 1 week of placebo administration were 1.63 for the escitalopram group and 3.42 for the paroxetine group. Significantly fewer post-therapy symptoms were observed in the escitalopram group than in the paroxetine group at all times.

Copyright © 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Adapted with permission from Baldwin DS, Cooper JA, Huusom AK, Hindmarch I. A double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, flexible-dose study to evaluate the tolerability, efficacy and effects of treatment discontinuation with escitalopram and paroxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(3):159–169.25

Suicidality

Suicidality was studied in a detailed meta-analysis42 conducted on data from 34 placebo-controlled studies on SSRIs. The analysis included >40,000 patients, approximately 2600 of whom had been treated with escitalopram. They found one instance of suicide, which occurred 6 days after treatment cessation. Another analysis of placebo-controlled studies43 specifically included patients with MDD or anxiety disorders that used escitalopram. They reported no suicides during the first 2 weeks of treatment or during the entire period of escitalopram (,24 weeks), but one suicide occurred in the placebo group. Furthermore, there was no indication of increased risk of nonfatal self-harm or suicidal thoughts among patients that received escitalopram compared with those that received placebo.43 Rather, escitalopram reduced the MADRS item-10 (“suicidal thought”) or HAM-D item-3 (“suicidal thought”) scores to a significantly greater extent than placebo.16,43,44 For an estimated >12 million patients with MDD and/or anxiety disorders treated with escitalopram, pharmacovigilance information revealed a suicide rate of 1.8 per 1 million patients; this rate was similar to that in patients treated with citalopram (2 per 1 million) and considerably lower than that in patients treated with tricyclic antidepressants (12 per 1 million) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) (14 per 1 million).43

Sexual dysfunction

A small, retrospective study45 (n = 47) indicated that two-thirds of patients with SSRI/SNRI-induced sexual dysfunction reported mild or marked improvements after switching to a regimen with escitalopram. However, several reports have suggested that escitalopram may be associated with increased sexual dysfunction in both men and women compared to bupropion or sertraline.46,47

QT prolongation

In a clinical trial in Japan,28 the QT interval in heart rate was examined with Fridericia’s correction formula (QTcF = QT/cubic root of relative risk). They found no difference in the QTcF values between patients that received escitalopram (10 mg/day) and those that received placebo. However, QTcF was significantly prolonged in patients treated with escitalopram (20 mg/day) compared to that of patients treated with placebo; nevertheless, no clinically problematic adverse events related to QT prolongation were observed. The trial report argued that caution was required in administering escitalopram to aged individuals, patients with liver dysfunction, patients with defective CYP2C19 activity, or patients that received other drugs that conferred a risk of QT prolongation.28

Overdosage

In a retrospective analysis48 of 28 patients that underwent a supratherapeutic ingestion of escitalopram (5–300 mg), only one patient reported adverse events. That patient was admitted to a hospital for persistent lethargy, but the outcome was good. However, when escitalopram is taken at high doses or in poly-substance ingestions, CNS depression may occur. Patients (n = 13) that had taken escitalopram (mean dosage 126 mg) as a coingestant in poly-substance ingestions exhibited CNS depression (54%), cardiovascular effects (54%), and ECG changes (23%).49 In one case report,50 after an overdose of escitalopram (100–200 mg), a 38-year-old man exhibited severe, prolonged serotonin syndrome and elevated serum escitalopram concentration.

Patient acceptability

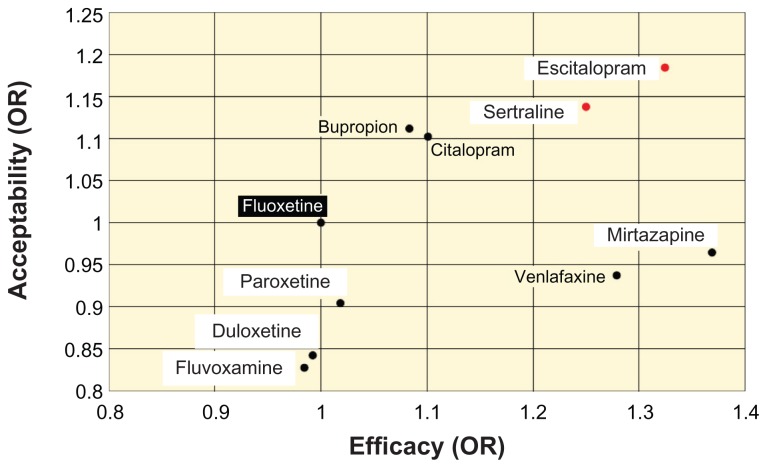

Another meta-analysis51 reported on the efficacy and patient acceptability of 12 new antidepressant drugs. In that meta-analysis, patient acceptability was defined as the persistence observed in taking a drug during an 8-week therapy. Among those 12 drugs, escitalopram was associated with the highest rate of patient acceptability. The result of that meta-analysis was illustrated for family physicians using fluoxetine as the standard (Figure 5).52

Figure 5.

Efficacy and patient acceptability of new antidepressant drugs.

Notes: The odds ratios (OR) of acceptability and efficacy were based on a value of 1 for fluoxetine. Acceptability of escitalopram was highest among the new antidepressant drugs examined. Copyright © 2009, The Family Physician’s Inquiries Network (FPIN). Adapted with permission from Patrick G, Combs G, Gavagan T. Initiating antidepressant therapy? Try these 2 drugs first. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(7):365–369.52

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

The rates of discontinuing therapy were analyzed among pooled data from double-blind, controlled studies of escitalopram versus paroxetine53 or duloxetine.54 The pooled data for paroxetine was derived from two studies24,25 that treated patients for 24 and 27 weeks, respectively. The discontinuation rate at the end of the study period was significantly lower for patients on escitalopram (16.8%) than for those on paroxetine (27.9%). When the reason for discontinuing therapy was restricted to adverse events, the discontinuation rates remained significantly lower for escitalopram (6.6%) than for paroxetine (11.7%).

The pooled data for duloxetine were derived from two studies31,32 that treated patients for 8 and 24 weeks, respectively. The discontinuation rate at the end of the study period was significantly lower for escitalopram (12.9%) than for duloxetine (24.6%). When the reason for discontinuing therapy was restricted to adverse events, the discontinuation rates remained significantly lower for escitalopram (4.6%) than for duloxetine (12.7%). Thus, escitalopram was associated with high therapy continuity.

MDD has a relatively high likelihood of recurrence. Thus, high therapy continuity with escitalopram represents an advantage for patients with this disease. There may be several reasons for the high therapy continuity of escitalopram. First, it has high efficacy and good tolerability, as shown in the clinical studies discussed previously. Thus, dropouts from escitalopram therapy due to insufficient efficacy or adverse events appeared to be limited. Furthermore, the demonstrated efficacy of escitalopram at an initial dose of 10 mg15 could be detected in the early therapeutic phase by patients.15,32 It was speculated that early signs of improvement most likely led to increased adherence, which, in turn, led to prevention of relapse37 and recurrence.38

The fact that escitalopram demonstrated preventive effects on relapse37 and recurrence38 represented major benefit to patients that desire to be reintegrated into society. For instance, for a company employee that wants to return to work, escitalopram may facilitate the return-to-work program, and, thus, the patient would expect to return to work smoothly.

Conclusion

This review provided an overview of escitalopram, focusing on its efficacy, tolerability, and patient acceptability in the management of MDD. In terms of efficacy, escitalopram was superior to placebo, and equal to or better than paroxetine or other SSRIs and SNRIs. In addition, escitalopram exerted a stable antidepressive action. Escitalopram had high tolerability, because adverse events related to escitalopram therapy were generally mild and temporary. Moreover, discontinuous symptoms were apparently milder than those related to paroxetine therapy.

The meta and pooled analyses showed high patient acceptability of escitalopram, which indicated that patients found it easy to continue this antidepressant therapy. Therefore, escitalopram can be regarded as an antidepressant drug associated with high therapy continuity, and the high efficacy of escitalopram is, in part, based on improved adherence due to high tolerability. In addition, the high therapy continuity of escitalopram can be expected to prevent relapses and recurrences. Comparison with placebo demonstrated that escitalopram had preventive effects on both relapse and recurrence of MDD.

A review by Murdock and Keam55 discussed the positioning of escitalopram in the management of MDD. Preliminary studies have suggested that escitalopram was as effective as other SSRIs and venlafaxine XR (venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release); furthermore, escitalopram may provide the advantage of cost-effectiveness and cost-utility. However, additional longer-term, comparative studies that evaluate specific efficacy, tolerability, health-related quality of life, and economic indices would be needed to determine definitively the position of escitalopram relative to other SSRIs and venlafaxine in the treatment of MDD. Nevertheless, available clinical and pharmacoeconomical data indicate that escitalopram is an effective first line option in the management of patients with MDD.

Because MDD recurs readily, it is important to select antidepressant drugs that allow high therapy continuity for pharmacological treatments. The effects of escitalopram highlighted in this review indicate that it is an antidepressant drug appropriate for first-line therapy.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Waugh J, Goa KL. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of major depressive and anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(5):343–362. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez C, Bergqvist PB, Brennum LT, et al. Escitalopram, the S-(+)-enantiomer of citalopram, is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with potent effects in animal models predictive of antidepressant and anxiolytic activities. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167(4):353–362. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1364-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen F, Larsen MB, Sanchez C, Wiborg O. The S-enantiomer of R,S-citalopram, increases inhibitor binding to the human serotonin transporter by an allosteric mechanism. Comparison with other serotonin transporter inhibitors. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(2):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mork A, Kreilgaard M, Sanchez C. The R-enantiomer of citalopram counteracts escitalopram-induced increase in extracellular 5-HT in the frontal cortex of freely moving rats. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45(2):167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Mansari M, Sanchez C, Chouvet G, Renaud B, Haddjeri N. Effects of acute and long-term administration of escitalopram and citalopram on serotonin neurotransmission: an in vivo electrophysiological study in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(7):1269–1277. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura M. Escitalopram oxalate. J Jpn Soc Hosp Pharm. 2012;48:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murdoch D, Keam SJ. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder. Drugs. 2005;65(16):2379–2404. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB. Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50(5):345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhillon S, Scott LJ, Plosker GL. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(9):763–790. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620090-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen F, Larsen MB, Neubauer HA, Sanchez C, Plenge P, Wiborg O. Characterization of an allosteric citalopram-binding site at the serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2005;92(1):21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neubauer HA, Hansen CG, Wiborg O. Dissection of an allosteric mechanism on the serotonin transporter: a cross-species study. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(4):1242–1250. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez C, Bogeso KP, Ebert B, Reines EH, Braestrup C. Escitalopram versus citalopram: the surprising role of the R-enantiomer. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174(2):163–176. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1865-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein N, Sacher J, Geiss-Granadia T, et al. Higher serotonin transporter occupancy after multiple dose administration of escitalopram compared to citalopram: an [123I]ADAM SPECT study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191(2):333–339. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0666-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1206–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(08)80047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade A, Michael Lemming O, Bang Hedegaard K. Escitalopram 10 mg/day is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17(3):95–102. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke WJ, Gergel I, Bose A. Fixed-dose trial of the single isomer SSRI escitalopram in depressed outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):331–336. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepola UM, Loft H, Reines EH. Escitalopram 10–20 mg/day) is effective and well tolerated in a placebo-controlled study in depression in primary care. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(4):211–217. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalit V, Appaya PM, Hegde RP, et al. Escitalopram versus citalopram and sertraline: a double-blind controlled, multi-centric trial in Indian patients with unipolar major depression. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46(4):333–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore N, Verdoux H, Fantino B. Prospective, multicentre, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram in outpatient treatment of major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):131–137. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ou JJ, Xun GL, Wu RR, et al. Efficacy and safety of escitalopram versus citalopram in major depressive disorder: a 6-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213(2–3):639–646. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1822-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yevtushenko VY, Belous AI, Yevtushenko YG, Gusinin SE, Buzik OJ, Agibalova TV. Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram versus citalopram in major depressive disorder: a 6-week, multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled study in adult outpatients. Clin Ther. 2007;29(11):2319–2332. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montgomery S, Hansen T, Kasper S. Efficacy of escitalopram compared to citalopram: a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(2):261–268. doi: 10.1017/S146114571000115X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trkulja V. Is escitalopram really relevantly superior to citalopram in treatment of major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of head-to-head randomized trials. Croat Med J. 2010;51(1):61–73. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2010.51.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulenger JP, Huusom AK, Florea I, Baekdal T, Sarchiapone M. A comparative study of the efficacy of long-term treatment with escitalopram and paroxetine in severely depressed patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(7):1331–1341. doi: 10.1185/030079906X115513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldwin DS, Cooper JA, Huusom AK, Hindmarch I. A double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, flexible-dose study to evaluate the tolerability, efficacy and effects of treatment discontinuation with escitalopram and paroxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(3):159–169. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000194377.88330.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirayasu Y. A dose-response and non-inferiority study evaluating the efficacy and safety of escitalopram in patients with major depressive disorder: a placebo- and paroxetine-controlled, double-blind, comparative study. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;14:883–899. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mochida Pharmacoceutical CO. L. Interview Form LEXAPRO Tab. 10 mg. 3rd ed. 2012. [Accessed November 15, 2012]. Available from: http://di.mt-pharma.co.jp/file/if/f_lex.pdf. Japanese.

- 28.Deliberation Result Report of LEXAPRO Tab. 10 mg. Pharmaceutical Food Station Examination Management Section, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Japan: 2011. 2011. [Accessed November 29, 2012]. Available from: http://www.info.pmda.go.jp/shinyaku/P201100076/79000500_22300AMX00517_A100_1.pdf. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao PX, Tang YL, Jiang F, et al. Escitalopram in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, parallel trial in a Chinese population. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(1):46–54. doi: 10.1002/da.20222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ventura D, Armstrong EP, Skrepnek GH, Haim Erder M. Escitalopram versus sertraline in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(2):245–250. doi: 10.1185/030079906X167273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan A, Bose A, Alexopoulos GS, Gommoll C, Li D, Gandhi C. Double-blind comparison of escitalopram and duloxetine in the acute treatment of major depressive disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(7):481–492. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200727070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wade A, Gembert K, Florea I. A comparative study of the efficacy of acute and continuation treatment with escitalopram versus duloxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(7):1605–1614. doi: 10.1185/030079907x210732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(9):1190–1196. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery SA, Huusom AK, Bothmer J. A randomised study comparing escitalopram with venlafaxine XR in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;50(1):57–64. doi: 10.1159/000078225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirayasu Y. A long-term administration study of escitalopram in patients with major depressive disorders. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;14:901–912. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirayasu Y. A long-term administration study of escitalopram in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;14:901–912. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorwood P, Weiller E, Lemming O, Katona C. Escitalopram prevents relapse in older patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(7):581–593. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000240823.94522.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornstein SG, Bose A, Li D, Saikali KG, Gandhi C. Escitalopram maintenance treatment for prevention of recurrent depression: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1767–1775. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Product Monograph-Issue 8-June 2009. Copenhagen: H. Lundbeck A/S; 2009. Cipralex®/Lexapro® (escitalopram) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lexapro® (escitalopram oxalate) tablets and oral solution [US prescribing information] St Louis, MO: Forest Laboratories, Inc; 2011. [Accessed May 10, 2011]. Available from: http://www.frx.com/pi/lexapro_pi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kennedy SH, Andersen HF, Thase ME. Escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(1):161–175. doi: 10.1185/03007990802622726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA’s safety review. BMJ. 2005;330(7488):385. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen AG. Escitalopram and suicidality in adult depression and anxiety. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(3):139–143. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200505000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bech P, Tanghoj P, Cialdella P, Andersen HF, Pedersen AG. Escitalopram dose-response revisited: an alternative psychometric approach to evaluate clinical effects of escitalopram compared to citalopram and placebo in patients with major depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;7(3):283–290. doi: 10.1017/S1461145704004365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashton AK, Mahmood A, Iqbal F. Improvements in SSRI/SNRI-induced sexual dysfunction by switching to escitalopram. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31(3):257–262. doi: 10.1080/00926230590513474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gersing K, Taylor L, Mereadith C. Outcome and adverse events for escitalopram and sertraline in a real-world setting [abstract no NR815] American Psychiatric Association. Annual Meeting 2005 New Research Abstracts; Atlanta, GA. 2005. pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clayton A, Wightman D, Modell JG. Effects in MDD on sexual functioning of bupropion XL, escitalopram, and placebo in depressed patiets [abstract no NR-818] American Psychiatric Association. Annual Meeting 2005 New Research Abstracts; Atlanta (GA). 2005. pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 48.LoVecchio F, Watts D, Winchell J, Knight J, McDowell T. Outcomes after supratherapeutic escitalopram ingestions. J Emerg Med. 2006;30(1):17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seifert SA, Meissner GK. Escitalopram overdose: a case series [abstract no 72] J Toxicol. 2004;42:495–496. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsen D, Dart R, Robinett M. Severe serotonin syndrome from escitalopram overdose [abstract no 72] J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2004;42:744–745. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patrick G, Combs G, Gavagan T. Initiating antidepressant therapy? Try these 2 drugs first. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(7):365–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kasper S, Baldwin DS, Larsson Lonn S, Boulenger JP. Superiority of escitalopram to paroxetine in the treatment of depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(4):229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam RW, Andersen HF, Wade AG. Escitalopram and duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of two trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(4):181–187. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282ffdedc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murdoch D, Keam SJ. Escitalopram: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder. Drugs. 2005;65(16):2380–2404. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]